Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

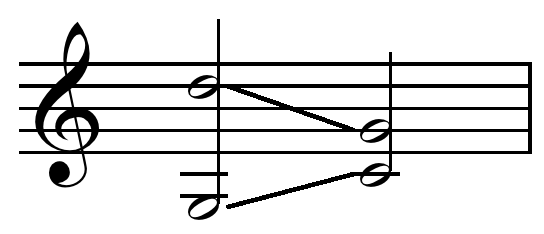

Consecutive fifths

View on Wikipedia

C to D

G.[2] ⓘ & ⓘ

In music, consecutive fifths or parallel fifths are progressions in which the interval of a perfect fifth is followed by a different perfect fifth between the same two musical parts (or voices): for example, from C to D in one part along with G to A in a higher part. Octave displacement is irrelevant to this aspect of musical grammar; for example, a parallel twelfth (i.e., an octave plus a fifth) is equivalent to a parallel fifth.[nb 1]

Parallel fifths are used in, and are evocative of, many musical genres, such as various kinds of Western folk and medieval music, as well as popular genres like rock music. However, parallel motion of perfect consonances (P1, P5, P8) is strictly forbidden in species counterpoint instruction (1725–present),[2] and during the common practice period, consecutive fifths were strongly discouraged. This was primarily due to the notion of voice leading in tonal music, in which "one of the basic goals ... is to maintain the relative independence of the individual parts."[3]

A common theory[citation needed] is that the presence of the 3rd harmonic of the harmonic series influenced the creation of the prohibition.[clarification needed]

Development of the prohibition

[edit]Singing in consecutive fifths may have originated from the accidental singing of a chant a perfect fifth above (or a perfect fourth below) the proper pitch.[citation needed] Whatever its origin, singing in parallel fifths became commonplace in early organum and conductus styles. Around 1300, Johannes de Garlandia became the first theorist to prohibit the practice.[4] However, parallel fifths were still common in 14th-century music. The early 15th-century composer Leonel Power likewise forbade the motion of "2 acordis perfite of one kynde, as 2 unisouns, 2 5ths, 2 8ths, 2 12ths, 2 15ths",[5] and it is with the transition to Renaissance-style counterpoint that the use of parallel perfect consonances was consistently avoided in practice. The convention dates approximately from 1450.[3] Composers avoided writing consecutive fifths between two independent parts, such as tenor and bass lines.

Consecutive fifths were usually considered forbidden, even if disguised (such as in a "horn fifth") or broken up by an intervening note (such as the mediant in a triad).[clarification needed] The interval may form part of a chord of any number of notes, and may be set well apart from the rest of the harmony, or finely interwoven in its midst. But the interval was always to be quit [followed?] by any movement that did not land on another fifth.

The prohibition concerning fifths did not just apply to perfect fifths. Some theorists also objected to the progression from a perfect fifth to a diminished fifth in parallel motion; for example, the progression from C and G to B and F (B and F forming a diminished fifth).

"The reason for avoiding parallel 5ths and 8ves has to do with the nature of counterpoint. The P8 and P5 are the most stable of intervals, and to link two voices through parallel motion at such intervals interferes with their independence much more than would parallel motion at 3rds or 6ths."[3] "Since the octave really represents a repetition of the same tone in a different register, if two or more octaves occur in succession, the result is a reduction in the number of voices; for example, in a two-voice setting, one of the voices would temporarily disappear, and along with it the rationale of the intended two-voice setting. The octave acts merely as a doubling; if, in a particular instance, it is not intended to act as such, this must be sufficiently emphasized by what precedes and follows it. But even the succession of two octaves brings the sense of doubling into the foreground. Of course, this must not be confused with an intentional doubling used to strengthen sonority, for which, however, strict counterpoint offers no motivation."[6] Similarly, "Parallel 8ves...reduce the number of voices...since the voice that [momentarily] doubles at the 8ve...is not an independent voice but merely a duplication. Parallel 8ves...may also confuse the functions of the voices...If the upper voice succession...is merely a duplication of the bass, then the actual soprano must be...the alto voice. This interpretation of course, makes no sense, for it turns the texture inside out."[7] "Parallel 5ths are avoided because the 5th, formed by scale degrees 1 and 5, is the primary harmonic interval, the interval that divides the scale and thus defines the key. The direct succession of two 5ths raises doubt concerning the key."[7]

The identification and avoidance of perfect fifths in the instruction of counterpoint and harmony helps to distinguish the more formal idiom of classical music from popular and folk musics, in which consecutive fifths commonly appear in the form of double tonics and shifts of level. The prohibition of consecutive fifths in European classical music originates not only from the requirement for contrary motion in counterpoint but also from a gradual and eventually self-conscious attempt to distance classical music from folk traditions. As Sir Donald Tovey explains in his discussion of Joseph Haydn's Symphony no. 88, "The trio is one of Haydn's finest pieces of rustic dance music, with hurdy-gurdy drones which shift in disregard of the rule forbidding consecutive fifths. The disregard is justified by the fact that the essential objection to consecutive fifths is that they produce the effect of shifting hurdy-gurdy drones."[8] A more contemporary example would be guitar power chords.

In the course of the 19th century, consecutive fifths became more common, arising out of new textures and new conceptions of propriety in voice leading generally. They even became a stylistic feature in the work of some composers, notably Chopin; and with the early 20th century and the breakdown of common-practice norms the prohibition became less and less relevant.[9]

Related progressions

[edit]Unequal fifths

[edit]Motion between perfect and diminished fifths is often avoided, with some avoiding only motion one way (diminished to perfect fifth or perfect to diminished fifth) or only if the bass is involved.[3] Notice that unequal fifths resemble similar rather than parallel motion, since a perfect fifth is seven semitones and a diminished fifth is six semitones.

Parallel octaves and fourths

[edit]

Consecutive fifths are avoided in part because they cause a loss of individuality between parts. This lack of individuality is even more pronounced when parts move in parallel octaves or in unison. These are therefore also generally forbidden among independently moving parts.[nb 2]

Parallel fourths (consecutive perfect fourths) are allowed, even though a P4 is the inversion and thus the complement of a P5.[1] The literature deals with them less systematically however, and theorists have often restricted their use.[citation needed] Theorists commonly disallow consecutive perfect fourths involving the lowest part, especially between the lowest part and the highest part. Since the beginning of the common practice period, it has been theorized that all dissonances should be properly resolved to a consonance (there are few exceptions). Therefore, parallel fourths above the bass are generally dismissed in voice leading as a series of consecutive unresolved dissonances. However, parallel fourths in upper voices (especially as part of a parallel "6-3" sonority) are common, and formed the basis of fifteenth century fauxbourdon style. As an example of this type of allowed parallel perfect fourth in common practice music, see the final movement of Mozart's A minor Piano sonata whose theme in bars 37–40 consists of parallel fourths in the right-hand part (but not above the bass).

Hidden consecutives

[edit]

G are approached in similar motion from below.[2] ⓘ

So-called hidden consecutives, also called direct or covered octaves or fifths,[11][nb 3] occur when two independent parts approach a single perfect fifth or octave by similar motion instead of oblique or contrary motion. A single fifth or octave approached this way is sometimes called an exposed fifth or exposed octave. Conventional style dictates that such a progression be avoided; but it is sometimes permitted under certain conditions, such as the following: the interval does not involve either the highest or the lowest part, the interval does not occur between both of those extreme parts, the interval is approached in one part by a semitone step, or the interval is approached in the higher part by step. The details differ considerably from period to period, and even among composers writing in the same period.

An important acceptable case of hidden fifths in the common practice period are horn fifths. Horn fifths arise from the limitation of valveless brass instruments to the notes of the harmonic series (hence their name). In all but their extreme high registers, these brass instruments are limited to the notes of the major triad. The typical two-instrument configuration would have the high instrument playing a scalar melody against a lower instrument confined to the notes of the tonic chord. Horn fifths occur when the upper voice is on the first three scale degrees.

Traditional horn fifths actually come in pairs. Begin with the upper instrument on the third scale degree and the lower instrument on the tonic. Then move the upper instrument to the second scale degree and the second instrument down to the fifth scale degree. Because the distance from 5 up to 2 is a perfect fifth, we have just created a hidden fifth by descending motion. The first instrument can then complete its descent to 1 as the lower instrument moves to 3. The second hidden fifth of the pair is obtained by making the upward maneuver a mirror image of the downward maneuver. These direct fifths are preferable to other less acceptable voice-leading alternatives including doubling the third scale degree at the octave, and limiting the low instrument to the use of only the first and fifth scale degrees. Although traditional horn fifths come in pairs and in passing, the acceptability of horn fifths has been generalized to any situation of hidden fifths where the top voice moves by step.

Special uses and exceptions in early music

[edit]Consecutive fifths are typically used to evoke the sound of music in medieval times or exotic places. The use of parallel fifths (or fourths) to refer to the sound of traditional Chinese or other kinds of Eastern music was once commonplace in film scores and songs. Since these passages are an obvious oversimplification and parody of the styles that they seek to evoke, this use of parallel fifths declined during the last half of the 20th century.

In the medieval period, large church organs and positive organs would often be permanently arranged for each single key to speak in a consecutive fifth.[citation needed] It is believed this practice dates to Roman times. A positive organ having this configuration has been reconstructed recently by Van der Putten and is housed in Groningen, and is used in an attempt to rediscover performance practice of the time.

In Iceland, the traditional song style known as tvísöngur, "twin-singing", goes back to the Middle Ages and is still taught in schools today. In this style, a melody is sung against itself, typically in parallel fifths.[12]

Georgian music frequently uses parallel fifths, and sometimes parallel major ninths above the fifths. This means that there are two sets of parallel fifths, one directly on top of the other. This is especially prominent in the sacred music of the Guria region, in which the pieces are sung a cappella by men. It is believed that this harmonic style dates from pre-Christian times.

Consecutive fifths (as well as fourths and octaves) are commonly used to mimic the sound of Gregorian plainsong. This practice is well-founded in early European musical traditions. Plainsong was originally sung in unison, not in fifths, but by the ninth century there is evidence that singing in parallel intervals (fifths, octaves, and fourths) commonly ornamented the performance of chant. This is documented in the anonymous ninth-century theory treatises known as Musica enchiriadis and its commentary Scolica enchiriadis. These treatises use Daseian music notation, based on four-note patterns called tetrachords, which easily notates parallel fifths. This notation predates Guido of Arezzo's solmization, which divides the scale into six-note patterns called hexachords, and the modern octave-based staff notation into which Guido's gamut evolved.

Mozart fifths

[edit]

In Brahms's essay "Octaven und Quinten" ("Octaves and fifths"), he identifies many cases of apparent consecutive fifths in the works of Mozart. Most of the examples he provides involve accompaniment figuration in small note values that moves in parallel fifths with a slower moving bass. The background voice-leading of such progressions is oblique motion, with the consecutive fifths resulting from the ornamentation of the sustaining voice with a chromatic lower neighbor. Such "Mozart fifths" occur in bars 254–255 of the Act I finale of Così fan Tutte, in bar 80 of the Act II sextet from Don Giovanni, in the opening of the last movement of the Violin Sonata in A Major, K. 526 and in bar 189 of the overture to Zauberflöte.

Another use of the term "Mozart fifths" results from the non-standard resolution of the German augmented sixth chord that Mozart used occasionally, such as in the retransition of the finale of the Jupiter Symphony (bars 221–222, second bassoon and basses), in the Sonata for Two Pianos in D Major, K. 448 (third movement, bars 276–277 (second piano)), and in the example at the right from Symphony No. 39 (Mozart). Mozart (and all common-practice composers) almost always resolves German augmented sixth chords to cadential 6

4 chords to avoid these fifths. The Jupiter example is unique in that Mozart spells the fifth enharmonically (A♭/D♯ to G/D♮) as a result of the progression arising from a B-major harmony (presented as a dominant of e-minor). Theorists have tried to make the case that this resolution of the augmented sixth chord is more frequently acceptable. "The parallel fifths [in the German sixth] arising from the natural progression to the dominant are always considered acceptable, except when occurring between soprano and bass. They are most often seen between tenor and bass. The third degree is, however, frequently tied over as a suspension, or repeated as an appoggiatura, before continuing down to the second degree".[14] However, seeing as the vast majority of German augmented sixth chords in common-practice works resolve to cadential six-four chords to avoid parallel fifths, it can be concluded that common-practice composers deemed these fifths undesirable in most situations.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Thus, the word "parallel" is not truly synonymous with "consecutive", as a fifth followed by another fifth approached with contrary motion would still count as consecutive fifths. The term parallel fifths may therefore be misleading because some consecutive fifths occur with contrary motion: from a true uncompounded fifth to a twelfth, for example. If parts move by oblique motion (for example, one part moving from a C to a higher C, and another part repeating a G higher than both of those Cs), the intervals are not considered to differ in the relevant way, so parallel fifths do not occur.

- ^ The restriction to independently moving parts is important. It has always been standard to double a part in unison or at the octave, even at several different octaves simultaneously, for the duration of a phrase or beyond. For contrapuntal and harmonic analysis this does not add new parts at all. By convention, common practice sometimes allows more transient parallel octaves, or even fifths, with certain melodic embellishments such as anticipations.(Piston 1987, pp. 306–312.)

- ^ The traditional terms for these progressions are as vague and variable as the traditional rules that govern them.[citation needed]

Sources

[edit]- ^ a b Kostka & Payne (1995). Tonal Harmony, p.85. Third Edition. ISBN 0-07-300056-6.

- ^ a b c Benward & Saker (2003). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.155. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ a b c d Kostka & Payne (1995), p.84.

- ^ Optima introductio in contrapunctum, c1300; Coussemaker, Edmond (1876), Scriptores de musica medii aevi, Vol. III, 12; as cited in Drabkin, William. "Consecutive fifths, consecutive octaves." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Meech, Sanford B. (1935). "Three Musical Treatises in English from a Fifteenth-Century Manuscript". Speculum. 10 (3): 242. doi:10.2307/2848378. JSTOR 2848378. S2CID 164028948.

- ^ Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker, p.110. (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers). Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- ^ a b Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept & Practice, p.50. Third edition. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

- ^ Tovey, Donald Francis. Essays in musical analysis, vol. 1, p. 142. Quoted in van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music, p. 210. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316121-4.

- ^ Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony, 5th edition revised DeVoto, Mark, pp. 309–312, 477–480. ISBN 978-0-393-95480-7.

- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.133. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Piston (1987), p. 32.

- ^ Árni Heimir Ingólfsson (2003). ‘These are the Things You Never Forget’: The Written and Oral Transmission of Icelandic Tvísöngur. Cambridge: Harvard University, Ph.D. dissertation.

- ^ Ellis, Mark R. (2010). A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth Sonority from Monteverdi to Mahler, p.5. ISBN 9780754663850.

- ^ Piston (1987), p. 422.

Further reading

[edit]- Jeppesen, Knud. Counterpoint: the polyphonic vocal style of the sixteenth century, English translation 1939, reprint by Dover, NY, 1992. ISBN 0-486-27036-X.

- Meech, Sanford. "Three Musical Treatises in English from a Fifteenth-Century Manuscript", Speculum X.3, July 1935.

- Mast, Paul (1980). "Brahms's Study, Octaven u. Quinten u. A., with Schenker's Commentary Translated", Music Forum V. Cited in Jonas (1982), p. 112n84.

- Ingólfsson, Árni Heimir. ‘These are the Things You Never Forget’: The Written and Oral Transmission of Icelandic Tvísöngur. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, 2003.

External links

[edit]- Hopkins, Pandora and Þorkell Sigurbjörnsson: Iceland, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 8 June 2006), Grove Music - Access by subscription only Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

Consecutive fifths

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Identification

A perfect fifth is a fundamental interval in music theory, spanning seven semitones on the chromatic scale and corresponding to a frequency ratio of 3:2 in just intonation.[6][7] This interval, such as from C to G, produces a consonant, stable sound due to its simple harmonic relationship.[6] Voice leading refers to the linear movement of individual melodic lines, or voices, in a polyphonic texture, where the goal is to maintain independence among voices through varied motion rather than uniform parallelism.[8] Consecutive fifths, also known as parallel fifths, occur when two voices successively form perfect fifth intervals while moving in the same direction—either both ascending or both descending—resulting in a loss of contrapuntal independence.[3] This motion can also involve similar motion that approximates parallelism, but strictly, it involves exact parallel perfect fifths between the same pair of voices over two or more consecutive chords.[9] To identify consecutive fifths visually in a score, examine the intervals between any two voices across successive chords; if a perfect fifth (e.g., C to G in the upper and lower voices) is followed by another perfect fifth in parallel motion (e.g., both voices moving up to D and A), it constitutes the error.[1] Auditory recognition often reveals a hollow, organ-like timbre, as the parallel intervals create a droning effect that merges the voices perceptually rather than highlighting their separation.[10] For instance, consider a simple two-voice example in C major: the upper voice plays C followed by D, while the lower voice plays G followed by A; this progression yields consecutive perfect fifths (C-G to D-A), visually parallel lines a fifth apart and aurally indistinct. Parallel octaves represent a similar issue but are considered more severe, as they further reduce voice independence by aligning pitches at the unison equivalent.[1][3]Theoretical Rationale for Avoidance

Parallel fifths, also known as consecutive perfect fifths, are avoided in traditional counterpoint primarily because they undermine the independence of individual voices, causing them to blend perceptually into a single melodic line rather than maintaining distinct polyphonic lines. This fusion occurs due to the acoustic properties of the perfect fifth (a 3:2 frequency ratio), where the overtones of the two notes align closely, resulting in a consonance overload that reduces the perceived separation between voices and creates a monophonic texture within a polyphonic framework.[11][8] Furthermore, parallel fifths weaken harmonic progression by producing open fifths, which lack the third necessary to distinguish between major and minor triads, thereby limiting the richness and clarity of harmonic texture. Historical theorists, such as Johann Joseph Fux in his seminal Gradus ad Parnassum (1725), described such parallel successions of perfect consonances as depriving the composition of its "sweetness," viewing them as primitive or empty in sound due to their failure to support varied linear interplay. In Fux's system, this prohibition applies across all five species of counterpoint to preserve linear variety and contrapuntal vitality.[12][13] Ideal voice leading counters this issue by favoring oblique, similar, or—most preferably—contrary motion, where voices move in opposite directions to enhance individuality and avoid parallel perfect intervals. For instance, if one voice moves by an interval , the accompanying voice should not replicate that exact motion if it results in parallel perfect fifths, as this would compromise voice separation; contrary motion, by contrast, promotes perceptual distinctness and structural balance.[14][15]Historical Development

Origins in Medieval and Renaissance Theory

In the medieval period, particularly from the 9th to the 12th centuries, parallel fifths were a foundational element of early polyphonic practices in organum, where a secondary voice typically moved in parallel motion with the principal chant at intervals of fourths or fifths to enrich the monophonic texture.[16] This approach, evident in Anglo-French organum documented around 1025, preserved the identity of the original melody while creating a sense of harmonic support, as seen in ecclesiastical compositions where parallelism at the fifth became prevalent by the 12th century.[16] The Notre Dame school, centered in Paris during the late 12th and early 13th centuries, exemplified this tradition through composers like Léonin (c. 1135–1201), whose Magnus liber organi featured organum purum with sustained parallel fifths and octaves over held notes of the chant.[17] Pérotin (c. 1155–1200 or later), building on Léonin, introduced greater rhythmic complexity and occasional oblique or contrary motion in clausulae and organa, marking an initial shift toward varied intervals that began to prioritize melodic independence over strict parallelism.[17] By the late 13th century, treatises began implying a preference for non-parallel motion to enhance contrapuntal variety. Franco of Cologne's Ars cantus mensurabilis (c. 1280), a seminal work on mensural notation, described polyphonic lines that could employ not only parallel but also oblique and contrary motion, suggesting an emerging emphasis on independent voice leading in measured music to avoid the homogeneity of early organum styles. This evolution continued into the Renaissance, where 15th-century polyphonists increasingly avoided consecutive fifths to achieve equality among voices.[18] Composers of the Burgundian school crafted masses and motets with careful voice leading that eschewed parallel perfect intervals, fostering a smoother, more interwoven texture. Similarly, composers like Josquin des Prez exemplified this practice in works featuring imitative counterpoint and varied interval progressions, ensuring distinct yet cohesive lines and reflecting the era's maturing polyphonic idiom.[19] Theorists of the time reinforced this avoidance through explicit warnings. Johannes Tinctoris, writing in the 1470s at the Aragonese court in Naples, condemned "false fifths"—consecutive perfect fifths in parallel motion—as violations of good counterpoint in his Liber de arte contrapuncti (1477), advocating instead for diverse interval successions to maintain contrapuntal integrity and avoid the archaic sound of medieval parallelism.[20] This prohibition solidified in a cappella vocal music, where clarity and balance were paramount, as parallel fifths could obscure individual lines in ensemble performance.[21] The cultural shift toward humanism in the 15th century further drove the demand for independent lines, as composers sought to express textual meaning with greater emotional nuance and rhetorical clarity. Reviving ancient Greek ideals of music's ethical and affective power, as explored in treatises influenced by Plato and Aristotle, humanists like Franchino Gaffurio and Gioseffo Zarlino emphasized polyphony that served the words, reducing organum-style parallelism to allow voices to articulate distinct ideas and affections in masses and motets.[22] In the 16th century, Zarlino further codified these principles in Le istitutioni harmoniche (1558), prohibiting parallels that disrupted voice independence.[23] This focus on text expression, evident in techniques like word-painting and the use of modes to evoke specific emotions, transformed consecutive fifths from a normative feature into a stylistic relic by the late Renaissance.[24]Codification in Baroque Counterpoint

In the Baroque era, the avoidance of consecutive fifths evolved from earlier informal guidelines into a formalized prohibition central to counterpoint pedagogy, emphasizing voice independence and polyphonic clarity. Johann Joseph Fux's seminal treatise Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) explicitly codified this rule across all five species of counterpoint, declaring parallel perfect fifths and octaves unacceptable as they undermine the linear independence of voices, drawing directly from the emulative style of Renaissance composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.[25] Fux's method, structured as a dialogue between master and pupil, instructed composers to avoid such parallels by ensuring contrary or oblique motion between voices, a principle that became foundational for training in voice leading.[26] This codification was reinforced by contemporary harmonic theorists, including Jean-Philippe Rameau in his Traité de l'harmonie réduite à ses principes naturels (1722), who integrated counterpoint rules into broader harmonic theory by advocating progressions that prevent parallel consonances, viewing them as disruptions to the fundamental bass and chordal functionality.[27] By the mid-18th century, Fux's influence permeated conservatory curricula across Europe, establishing the ban as a standard for compositional exercises and making it a cornerstone of formal music education in institutions like the Paris Conservatoire.[28] In practical application, Baroque composers adhered strictly to this rule to sustain polyphonic density in genres such as fugues and chorales. Johann Sebastian Bach, for instance, meticulously avoided consecutive fifths in his chorale harmonizations to preserve melodic distinctiveness amid dense textures, with analyses of his 371 chorales revealing only rare instances, often in transitional passages.[29] Similarly, Arcangelo Corelli defended his trio sonatas against accusations of parallels in a 1710 letter, clarifying that apparent fifths resulted from voice crossing rather than true consecutives, underscoring the era's rigorous standards.[30] George Frideric Handel followed suit in his oratorios and operas, employing varied voice leading to evade such intervals and enhance contrapuntal vitality. The rise of figured bass after 1600, popularized in works by Claudio Monteverdi and others, shifted compositional emphasis toward harmonic accompaniment, yet counterpoint prohibitions like the ban on consecutive fifths endured in theoretical training and orchestral writing, bridging Renaissance polyphony with Baroque forms. This persistence ensured the rule's integration into keyboard and ensemble practices, influencing composers from the late 17th to mid-18th centuries.Related Voice Leading Concepts

Parallel Octaves and Fourths

Parallel octaves occur when two voices maintain an octave interval while moving in the same direction by the same interval, effectively producing a unison at double the pitch and eliminating any distinction between the voices.[31] This complete fusion undermines the independence of lines essential to contrapuntal texture, creating a monophonic effect despite the notated polyphony.[3] In contrast, parallel fourths involve two voices sustaining a perfect fourth while progressing similarly; as the inversion of a fifth, they generate a hollow, organum-like resonance that weakens voice separation but to a lesser degree than octaves.[31] These progressions are less severe for fourths because the interval's dissonant quality in two-voice settings (per traditional classifications) limits their fusion compared to the pure consonance of octaves.[12] Theoretically, parallel octaves, fifths, and fourths all represent perfect consonances in parallel motion, which theorists like Johann Joseph Fux proscribed to preserve linear autonomy in counterpoint. Octaves are the most egregious due to octave equivalence, where voices sound as one regardless of register; fifths follow closely for their acoustic hollowness, while fourths—often treated as dissonances above the bass—are forbidden primarily when the upper voice leads by step, as this mimics organum parallels without full equivalence.[31] Like consecutive fifths, the primary parallel consonance issue, these motions reduce contrapuntal vitality by locking intervals rigidly.[3] For illustration, consider a simple two-voice example in C major: an upper voice moving from C4 to D4 paired with a lower voice from G3 to A3 forms consecutive perfect fifths (C-G to D-A), weakening independence; replacing the lower voice with C3 to D3 yields parallel octaves (C4-C3 to D4-D3), fully merging the lines; similarly, an upper voice from F4 to G4 with a lower from C3 to D3 creates parallel fourths (F4-C3 to G4-D3), producing a less intrusive but still undesirable hollowness.[31] Historically, parallel octaves and fourths have been prohibited alongside fifths since the Renaissance, as polyphony evolved beyond early organum practices to emphasize distinct voices, though octaves drew more universal condemnation for their total erasure of individuality. This stance was codified in Baroque treatises, influencing counterpoint pedagogy through the Classical era.Hidden Consecutives

Hidden consecutives, also known as concealed or indirect fifths and octaves, arise in voice leading when two non-adjacent voices progress in similar motion to a perfect fifth or octave, typically involving a leap in one voice and stepwise motion in the other, thereby implying parallel motion without overt stepwise progression in both.[32] This subtler form of parallel perfect intervals contrasts with direct consecutives, where both voices move stepwise in the same direction.[12] To identify hidden consecutives, analysts must examine all pairs of voices in a texture, including outer voices like soprano and bass, rather than limiting checks to adjacent parts; they are particularly common in four-voice harmony, where inner voices may provide variety but outer voices inadvertently align in parallel perfect intervals.[32] Such occurrences often emerge at points of harmonic change, such as chord progressions, and require scrutinizing motion directions and interval outcomes across the score.[12] Theoretically, hidden consecutives undermine the independence of voices by suggesting parallelism that weakens contrapuntal texture, though they are deemed less severe than direct parallels; Johann Joseph Fux in Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) identifies them as faults where one fifth is open and the other concealed, potentially standing out through rhythmic diminution.[12] Similarly, Luigi Cherubini in his Cours de Contrepoint et de Fugue (1835) prohibits concealed fifths and octaves in three-part counterpoint between extreme parts or an intermediate part and an extreme, classifying them as violations akin to those in two-part writing.[33] A representative example appears in a root-position I to V progression in C major: the soprano moves stepwise from F4 to G4 (a second upward), while the bass leaps from C3 to G3 (a fifth upward), forming a hidden octave between these outer voices as the overall harmony shifts from tonic to dominant; this can be visualized on staff notation as:Treble clef: F4 -- G4

Bass clef: C3 -- G3

Treble clef: F4 -- G4

Bass clef: C3 -- G3