Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

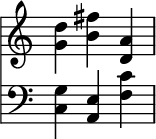

Perfect fifth

View on Wikipedia

| Inverse | perfect fourth |

|---|---|

| Name | |

| Other names | diapente |

| Abbreviation | P5 |

| Size | |

| Semitones | 7 |

| Interval class | 5 |

| Just interval | 3:2 |

| Cents | |

| 12-Tone equal temperament | 700 |

| Just intonation | 701.955[1] |

In music theory, a perfect fifth is the musical interval corresponding to a pair of pitches with a frequency ratio of 3:2, or very nearly so.

In classical music from Western culture, a fifth is the interval from the first to the last of the first five consecutive notes in a diatonic scale.[2] The perfect fifth (often abbreviated P5) spans seven semitones, while the diminished fifth spans six and the augmented fifth spans eight semitones. For example, the interval from C to G is a perfect fifth, as the note G lies seven semitones above C.

The perfect fifth may be derived from the harmonic series as the interval between the second and third harmonics. In a diatonic scale, the dominant note is a perfect fifth above the tonic note.

The perfect fifth is more consonant, or stable, than any other interval except the unison and the octave. It occurs above the root of all major and minor chords (triads) and their extensions. Until the late 19th century, it was often referred to by one of its Greek names, diapente.[3] Its inversion is the perfect fourth. The octave of the fifth is the twelfth.

A perfect fifth is at the start of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star"; the pitch of the first "twinkle" is the root note and the pitch of the second "twinkle" is a perfect fifth above it.

Alternative definitions

[edit]The term perfect identifies the perfect fifth as belonging to the group of perfect intervals (including the unison, perfect fourth, and octave), so called because of their simple pitch relationships and their high degree of consonance.[4] When an instrument with only twelve notes to an octave (such as the piano) is tuned using Pythagorean tuning, one of the twelve fifths (the wolf fifth) sounds severely discordant and can hardly be qualified as "perfect", if this term is interpreted as "highly consonant". However, when using correct enharmonic spelling, the wolf fifth in Pythagorean tuning or meantone temperament is actually not a perfect fifth but a diminished sixth (for instance G♯–E♭).

Perfect intervals are also defined as those natural intervals whose inversions are also natural, where natural, as opposed to altered, designates those intervals between a base note and another note in the major diatonic scale starting at that base note (for example, the intervals from C to C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, with no sharps or flats); this definition leads to the perfect intervals being only the unison, fourth, fifth, and octave, without appealing to degrees of consonance.[5]

The term perfect has also been used as a synonym of just, to distinguish intervals tuned to ratios of small integers from those that are "tempered" or "imperfect" in various other tuning systems, such as equal temperament.[6][7] The perfect unison has a pitch ratio 1:1, the perfect octave 2:1, the perfect fourth 4:3, and the perfect fifth 3:2.

Within this definition, other intervals may also be called perfect, for example a perfect third (5:4)[8] or a perfect major sixth (5:3).[9]

Other qualities

[edit]In addition to perfect, there are two other kinds, or qualities, of fifths: the diminished fifth, which is one chromatic semitone smaller, and the augmented fifth, which is one chromatic semitone larger. In terms of semitones, these are equivalent to the tritone (or augmented fourth), and the minor sixth, respectively.

Pitch ratio

[edit]

The justly tuned pitch ratio of a perfect fifth is 3:2 (also known, in early music theory, as a hemiola),[11][12] meaning that the upper note makes three vibrations in the same amount of time that the lower note makes two. The just perfect fifth can be heard when a violin is tuned: if adjacent strings are adjusted to the exact ratio of 3:2, the result is a smooth and consonant sound, and the violin sounds in tune.

Keyboard instruments such as the piano normally use an equal-tempered version of the perfect fifth, enabling the instrument to play in all keys. In 12-tone equal temperament, the frequencies of the tempered perfect fifth are in the ratio or approximately 1.498307. An equally tempered perfect fifth, defined as 700 cents, is about two cents narrower than a just perfect fifth, which is approximately 701.955 cents.

Kepler explored musical tuning in terms of integer ratios, and defined a "lower imperfect fifth" as a 40:27 pitch ratio, and a "greater imperfect fifth" as a 243:160 pitch ratio.[13] His lower perfect fifth ratio of 1.48148 (680 cents) is much more "imperfect" than the equal temperament tuning (700 cents) of 1.4983 (relative to the ideal 1.50). Hermann von Helmholtz uses the ratio 301:200 (708 cents) as an example of an imperfect fifth; he contrasts the ratio of a fifth in equal temperament (700 cents) with a "perfect fifth" (3:2), and discusses the audibility of the beats that result from such an "imperfect" tuning.[14]

Use in harmony

[edit]W. E. Heathcote describes the octave as representing the prime unity within the triad, a higher unity produced from the successive process: "first Octave, then Fifth, then Third, which is the union of the two former".[15] Hermann von Helmholtz argues that some intervals, namely the perfect fourth, fifth, and octave, "are found in all the musical scales known", though the editor of the English translation of his book notes the fourth and fifth may be interchangeable or indeterminate.[16]

The perfect fifth is a basic element in the construction of major and minor triads, and their extensions. Because these chords occur frequently in much music, the perfect fifth occurs just as often. However, since many instruments contain a perfect fifth as an overtone, it is not unusual to omit the fifth of a chord (especially in root position).

The perfect fifth is also present in seventh chords as well as "tall tertian" harmonies (harmonies consisting of more than four tones stacked in thirds above the root). The presence of a perfect fifth can in fact soften the dissonant intervals of these chords, as in the major seventh chord in which the dissonance of a major seventh is softened by the presence of two perfect fifths.

Chords can also be built by stacking fifths, yielding quintal harmonies. Such harmonies are present in more modern music, such as the music of Paul Hindemith. This harmony also appears in Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in the "Dance of the Adolescents" where four C trumpets, a piccolo trumpet, and one horn play a five-tone B-flat quintal chord.[17]

Bare fifth, open fifth, or empty fifth

[edit]

A bare fifth, open fifth or empty fifth is a chord containing only a perfect fifth with no third. The closing chords of Pérotin's Viderunt omnes and Sederunt Principes, Guillaume de Machaut's Messe de Nostre Dame, the Kyrie in Mozart's Requiem, and the first movement of Bruckner's Ninth Symphony are all examples of pieces ending on an open fifth. These chords are common in Medieval music, Sacred Harp singing, and throughout rock music. In hard rock, metal, and punk music, overdriven or distorted electric guitar can make thirds sound muddy while the bare fifths remain crisp. In addition, fast chord-based passages are made easier to play by combining the four most common guitar hand shapes into one. Rock musicians refer to them as power chords. Power chords often include octave doubling (i.e., their bass note is doubled one octave higher, e.g. F3–C4–F4).

An empty fifth is sometimes used in traditional music, e.g., in Asian music and in some Andean music genres of pre-Columbian origin, such as k'antu and sikuri. The same melody is being led by parallel fifths and octaves during all the piece.

Western composers may use the interval to give a passage an exotic flavor.[18] Empty fifths are also sometimes used to give a cadence an ambiguous quality, as the bare fifth does not indicate a major or minor tonality.

Use in tuning and tonal systems

[edit]The just perfect fifth, together with the octave, forms the basis of Pythagorean tuning. A slightly narrowed perfect fifth is likewise the basis for meantone tuning.[citation needed]

The circle of fifths is a model of pitch space for the chromatic scale (chromatic circle), which considers nearness as the number of perfect fifths required to get from one note to another, rather than chromatic adjacency.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^

- ^ Don Michael Randel (2003), "Interval", Harvard Dictionary of Music, fourth edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press): p. 413.

- ^ William Smith; Samuel Cheetham (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities. London: John Murray. p. 550. ISBN 9780790582290.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Piston, Walter; de Voto, Mark (1987). Harmony (5th ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton. p. 15. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

Octaves, perfect intervals, thirds, and sixths are classified as being 'consonant intervals', but thirds and sixths are qualified as 'imperfect consonances'.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenneth McPherson Bradley (1908). Harmony and Analysis. C. F. Summy. p. 17.

- ^ Charles Knight (1843). Penny Cyclopaedia. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. p. 356.

- ^ John Stillwell (2006). Yearning for the Impossible. A. K. Peters. p. 21. ISBN 1-56881-254-X.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth tempered.

- ^ Llewelyn Southworth Lloyd (1970). Music and Sound. Ayer Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 0-8369-5188-3.

- ^ John Broadhouse (1892). Musical Acoustics. W. Reeves. p. 277.

perfect major sixth ratio.

- ^ a b John Fonville (Summer 1991). "Ben Johnston's Extended Just Intonation: A Guide for Interpreters". Perspectives of New Music. 29 (2): 109 (106–137). doi:10.2307/833435. JSTOR 833435.

- ^ Willi Apel (1972). "Hemiola, hemiolia". Harvard Dictionary of Music (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 382. ISBN 0-674-37501-7.

- ^ Randel, Don Michael, ed. (2003). "Hemiola, hemiola". The Harvard Dictionary of Music: Fourth Edition. Harvard Dictionary of Music (4th ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 389. ISBN 0-674-01163-5.

- ^ Johannes Kepler (2004). Stephen Hawking (ed.). Harmonies of the World. Running Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-7624-2018-9.

- ^ Hermann von Helmholtz (1912). On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. Longmans, Green. pp. 199, 313. ISBN 9781419178931.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth Helmholtz tempered

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ W. E. Heathcote (1888), "Introductory Essay", in Moritz Hauptmann, The Nature of Harmony and Metre, translated and edited by W. E. Heathcote (London: Swan Sonnenschein), p. xx.

- ^ Hermann von Helmholtz (1912). On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music. Longmans, Green. p. 253. ISBN 9781419178931.

perfect fifth imperfect fifth Helmholtz tempered

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Piston & DeVoto 1987, pp. 503–505.

- ^ Scott Miller, "Inside The King and I", New Line Theatre, accessed December 28, 2012

![{\displaystyle ({\sqrt[{12}]{2}})^{7}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bb23db3674c3081c7995b2e899d4d6c8f36159bb)