Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Partially ordered set

View on Wikipedia| Transitive binary relations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

in general (it might, or might not, hold). For example, that every equivalence relation is symmetric, but not necessarily antisymmetric, is indicated by All definitions tacitly require the homogeneous relation be transitive: for all if and then |

In mathematics, especially order theory, a partial order on a set is an arrangement such that, for certain pairs of elements, one precedes the other. The word partial is used to indicate that not every pair of elements needs to be comparable; that is, there may be pairs for which neither element precedes the other. Partial orders thus generalize total orders, in which every pair is comparable.

Formally, a partial order is a homogeneous binary relation that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive. A partially ordered set (poset for short) is an ordered pair consisting of a set (called the ground set of ) and a partial order on . When the meaning is clear from context and there is no ambiguity about the partial order, the set itself is sometimes called a poset.

Partial order relations

[edit]The term partial order usually refers to the reflexive partial order relations, referred to in this article as non-strict partial orders. However some authors use the term for the other common type of partial order relations, the irreflexive partial order relations, also called strict partial orders. Strict and non-strict partial orders can be put into a one-to-one correspondence, so for every strict partial order there is a unique corresponding non-strict partial order, and vice versa.

Partial orders

[edit]A reflexive, weak,[1] or non-strict partial order,[2] commonly referred to simply as a partial order, is a homogeneous relation ≤ on a set that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive. That is, for all it must satisfy:

- Reflexivity: , i.e. every element is related to itself.

- Antisymmetry: if and then , i.e. no two distinct elements precede each other.

- Transitivity: if and then .

A non-strict partial order is also known as an antisymmetric preorder.

Strict partial orders

[edit]An irreflexive, strong,[1] or strict partial order is a homogeneous relation < on a set that is irreflexive, asymmetric and transitive; that is, it satisfies the following conditions for all

- Irreflexivity: , i.e. no element is related to itself (also called anti-reflexive).

- Asymmetry: if then not .

- Transitivity: if and then .

A transitive relation is asymmetric if and only if it is irreflexive.[3] So the definition is the same if it omits either irreflexivity or asymmetry (but not both).

A strict partial order is also known as a strict preorder.

Correspondence of strict and non-strict partial order relations

[edit]

Strict and non-strict partial orders on a set are closely related. A non-strict partial order may be converted to a strict partial order by removing all relationships of the form that is, the strict partial order is the set where is the identity relation on and denotes set subtraction. Conversely, a strict partial order < on may be converted to a non-strict partial order by adjoining all relationships of that form; that is, is a non-strict partial order. Thus, if is a non-strict partial order, then the corresponding strict partial order < is the irreflexive kernel given by Conversely, if < is a strict partial order, then the corresponding non-strict partial order is the reflexive closure given by:

Dual orders

[edit]The dual (or opposite) of a partial order relation is defined by letting be the converse relation of , i.e. if and only if . The dual of a non-strict partial order is a non-strict partial order,[4] and the dual of a strict partial order is a strict partial order. The dual of a dual of a relation is the original relation.

Notation

[edit]Given a set and a partial order relation, typically the non-strict partial order , we may uniquely extend our notation to define four partial order relations and , where is a non-strict partial order relation on , is the associated strict partial order relation on (the irreflexive kernel of ), is the dual of , and is the dual of . Strictly speaking, the term partially ordered set refers to a set with all of these relations defined appropriately. But practically, one need only consider a single relation, or , or, in rare instances, the non-strict and strict relations together, .[5]

The term ordered set is sometimes used as a shorthand for partially ordered set, as long as it is clear from the context that no other kind of order is meant. In particular, totally ordered sets can also be referred to as "ordered sets", especially in areas where these structures are more common than posets. Some authors use different symbols than such as [6] or [7] to distinguish partial orders from total orders.

When referring to partial orders, should not be taken as the complement of . The relation is the converse of the irreflexive kernel of , which is always a subset of the complement of , but is equal to the complement of if, and only if, is a total order.[a]

Alternative definitions

[edit]Another way of defining a partial order, found in computer science, is via a notion of comparison. Specifically, given as defined previously, it can be observed that two elements x and y may stand in any of four mutually exclusive relationships to each other: either x < y, or x = y, or x > y, or x and y are incomparable. This can be represented by a function that returns one of four codes when given two elements.[8][9] This definition is equivalent to a partial order on a setoid, where equality is taken to be a defined equivalence relation rather than set equality.[10]

Wallis defines a more general notion of a partial order relation as any homogeneous relation that is transitive and antisymmetric. This includes both reflexive and irreflexive partial orders as subtypes.[1]

A finite poset can be visualized through its Hasse diagram.[11] Specifically, taking a strict partial order relation , a directed acyclic graph (DAG) may be constructed by taking each element of to be a node and each element of to be an edge. The transitive reduction of this DAG[b] is then the Hasse diagram. Similarly this process can be reversed to construct strict partial orders from certain DAGs. In contrast, the graph associated to a non-strict partial order has self-loops at every node and therefore is not a DAG; when a non-strict order is said to be depicted by a Hasse diagram, actually the corresponding strict order is shown.

Examples

[edit]

Standard examples of posets arising in mathematics include:

- The real numbers, or in general any totally ordered set, ordered by the standard less-than-or-equal relation ≤, is a partial order.

- On the real numbers , the usual less than relation < is a strict partial order. The same is also true of the usual greater than relation > on .

- By definition, every strict weak order is a strict partial order.

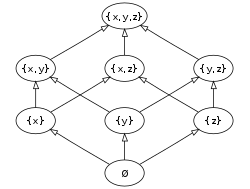

- The set of subsets of a given set (its power set) ordered by inclusion (see Fig. 1). Similarly, the set of sequences ordered by subsequence, and the set of strings ordered by substring.

- The set of natural numbers equipped with the relation of divisibility. (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 6)

- The vertex set of a directed acyclic graph ordered by reachability.

- The set of subspaces of a vector space ordered by inclusion.

- For a partially ordered set P, the sequence space containing all sequences of elements from P, where sequence a precedes sequence b if every item in a precedes the corresponding item in b. Formally, if and only if for all ; that is, a componentwise order.

- For a set X and a partially ordered set P, the function space containing all functions from X to P, where f ≤ g if and only if f(x) ≤ g(x) for all

- A fence, a partially ordered set defined by an alternating sequence of order relations a < b > c < d ...

- The set of events in special relativity and, in most cases,[c] general relativity, where for two events X and Y, X ≤ Y if and only if Y is in the future light cone of X. An event Y can be causally affected by X only if X ≤ Y.

One familiar example of a partially ordered set is a collection of people ordered by genealogical descendancy. Some pairs of people bear the descendant-ancestor relationship, but other pairs of people are incomparable, with neither being a descendant of the other.

Orders on the Cartesian product of partially ordered sets

[edit]In order of increasing strength, i.e., decreasing sets of pairs, three of the possible partial orders on the Cartesian product of two partially ordered sets are (see Fig. 4):

- the lexicographical order: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if a < c or (a = c and b ≤ d);

- the product order: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if a ≤ c and b ≤ d;

- the reflexive closure of the direct product of the corresponding strict orders: (a, b) ≤ (c, d) if (a < c and b < d) or (a = c and b = d).

All three can similarly be defined for the Cartesian product of more than two sets.

Applied to ordered vector spaces over the same field, the result is in each case also an ordered vector space.

See also orders on the Cartesian product of totally ordered sets.

Sums of partially ordered sets

[edit]Another way to combine two (disjoint) posets is the ordinal sum[12] (or linear sum),[13] Z = X ⊕ Y, defined on the union of the underlying sets X and Y by the order a ≤Z b if and only if:

- a, b ∈ X with a ≤X b, or

- a, b ∈ Y with a ≤Y b, or

- a ∈ X and b ∈ Y.

If two posets are well-ordered, then so is their ordinal sum.[14]

Series-parallel partial orders are formed from the ordinal sum operation (in this context called series composition) and another operation called parallel composition. Parallel composition is the disjoint union of two partially ordered sets, with no order relation between elements of one set and elements of the other set.

Derived notions

[edit]The examples use the poset consisting of the set of all subsets of a three-element set ordered by set inclusion (see Fig. 1).

- a is related to b when a ≤ b. This does not imply that b is also related to a, because the relation need not be symmetric. For example, is related to but not the reverse.

- a and b are comparable if a ≤ b or b ≤ a. Otherwise they are incomparable. For example, and are comparable, while and are not.

- A total order or linear order is a partial order under which every pair of elements is comparable, i.e. trichotomy holds. For example, the natural numbers with their standard order.

- A chain is a subset of a poset that is a totally ordered set. For example, is a chain.

- An antichain is a subset of a poset in which no two distinct elements are comparable. For example, the set of singletons

- An element a is said to be strictly less than an element b, if a ≤ b and For example, is strictly less than

- An element a is said to be covered by another element b, written a ⋖ b (or a <: b), if a is strictly less than b and no third element c fits between them; formally: if both a ≤ b and are true, and a ≤ c ≤ b is false for each c with Using the strict order <, the relation a ⋖ b can be equivalently rephrased as "a < b but not a < c < b for any c". For example, is covered by but is not covered by

Extrema

[edit]

There are several notions of "greatest" and "least" element in a poset notably:

- Greatest element and least element: An element is a greatest element if for every element An element is a least element if for every element A poset can only have one greatest or least element. In our running example, the set is the greatest element, and is the least.

- Maximal elements and minimal elements: An element is a maximal element if there is no element such that Similarly, an element is a minimal element if there is no element such that If a poset has a greatest element, it must be the unique maximal element, but otherwise there can be more than one maximal element, and similarly for least elements and minimal elements. In our running example, and are the maximal and minimal elements. Removing these, there are 3 maximal elements and 3 minimal elements (see Fig. 5).

- Upper and lower bounds: For a subset A of P, an element x in P is an upper bound of A if a ≤ x, for each element a in A. In particular, x need not be in A to be an upper bound of A. Similarly, an element x in P is a lower bound of A if a ≥ x, for each element a in A. A greatest element of P is an upper bound of P itself, and a least element is a lower bound of P. In our example, the set is an upper bound for the collection of elements

As another example, consider the positive integers, ordered by divisibility: 1 is a least element, as it divides all other elements; on the other hand this poset does not have a greatest element. This partially ordered set does not even have any maximal elements, since any g divides for instance 2g, which is distinct from it, so g is not maximal. If the number 1 is excluded, while keeping divisibility as ordering on the elements greater than 1, then the resulting poset does not have a least element, but any prime number is a minimal element for it. In this poset, 60 is an upper bound (though not a least upper bound) of the subset which does not have any lower bound (since 1 is not in the poset); on the other hand 2 is a lower bound of the subset of powers of 2, which does not have any upper bound. If the number 0 is included, this will be the greatest element, since this is a multiple of every integer (see Fig. 6).

Mappings between partially ordered sets

[edit]Given two partially ordered sets (S, ≤) and (T, ≼), a function is called order-preserving, or monotone, or isotone, if for all implies f(x) ≼ f(y). If (U, ≲) is also a partially ordered set, and both and are order-preserving, their composition is order-preserving, too. A function is called order-reflecting if for all f(x) ≼ f(y) implies If f is both order-preserving and order-reflecting, then it is called an order-embedding of (S, ≤) into (T, ≼). In the latter case, f is necessarily injective, since implies and in turn according to the antisymmetry of If an order-embedding between two posets S and T exists, one says that S can be embedded into T. If an order-embedding is bijective, it is called an order isomorphism, and the partial orders (S, ≤) and (T, ≼) are said to be isomorphic. Isomorphic orders have structurally similar Hasse diagrams (see Fig. 7a). It can be shown that if order-preserving maps and exist such that and yields the identity function on S and T, respectively, then S and T are order-isomorphic.[15]

For example, a mapping from the set of natural numbers (ordered by divisibility) to the power set of natural numbers (ordered by set inclusion) can be defined by taking each number to the set of its prime divisors. It is order-preserving: if x divides y, then each prime divisor of x is also a prime divisor of y. However, it is neither injective (since it maps both 12 and 6 to ) nor order-reflecting (since 12 does not divide 6). Taking instead each number to the set of its prime power divisors defines a map that is order-preserving, order-reflecting, and hence an order-embedding. It is not an order-isomorphism (since it, for instance, does not map any number to the set ), but it can be made one by restricting its codomain to Fig. 7b shows a subset of and its isomorphic image under g. The construction of such an order-isomorphism into a power set can be generalized to a wide class of partial orders, called distributive lattices; see Birkhoff's representation theorem.

Number of partial orders

[edit]Sequence A001035 in OEIS gives the number of partial orders on a set of n labeled elements:

| Elements | Any | Transitive | Reflexive | Symmetric | Preorder | Partial order | Total preorder | Total order | Equivalence relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 512 | 171 | 64 | 64 | 29 | 19 | 13 | 6 | 5 |

| 4 | 65,536 | 3,994 | 4,096 | 1,024 | 355 | 219 | 75 | 24 | 15 |

| n | 2n2 | 2n(n−1) | 2n(n+1)/2 | ∑n k=0 k!S(n, k) |

n! | ∑n k=0 S(n, k) | |||

| OEIS | A002416 | A006905 | A053763 | A006125 | A000798 | A001035 | A000670 | A000142 | A000110 |

Note that S(n, k) refers to Stirling numbers of the second kind.

The number of strict partial orders is the same as that of partial orders.

If the count is made only up to isomorphism, the sequence 1, 1, 2, 5, 16, 63, 318, ... (sequence A000112 in the OEIS) is obtained.

Subposets

[edit]A poset is called a subposet of another poset provided that is a subset of and is a subset of . The latter condition is equivalent to the requirement that for any and in (and thus also in ), if then .

If is a subposet of and furthermore, for all and in , whenever we also have , then we call the subposet of induced by , and write .

Linear extension

[edit]A partial order on a set is called an extension of another partial order on provided that for all elements whenever it is also the case that A linear extension is an extension that is also a linear (that is, total) order. As a classic example, the lexicographic order of totally ordered sets is a linear extension of their product order. Every partial order can be extended to a total order (order-extension principle).[16]

In computer science, algorithms for finding linear extensions of partial orders (represented as the reachability orders of directed acyclic graphs) are called topological sorting.

In category theory

[edit]Every poset (and every preordered set) may be considered as a category where, for objects and there is at most one morphism from to More explicitly, let hom(x, y) = {(x, y)} if x ≤ y (and otherwise the empty set) and Such categories are sometimes called posetal.

Posets are equivalent to one another if and only if they are isomorphic. In a poset, the smallest element, if it exists, is an initial object, and the largest element, if it exists, is a terminal object. Also, every preordered set is equivalent to a poset. Finally, every subcategory of a poset is isomorphism-closed.

Partial orders in topological spaces

[edit]If is a partially ordered set that has also been given the structure of a topological space, then it is customary to assume that is a closed subset of the topological product space Under this assumption partial order relations are well behaved at limits in the sense that if and and for all then [17]

Intervals

[edit]A convex set in a poset P is a subset I of P with the property that, for any x and y in I and any z in P, if x ≤ z ≤ y, then z is also in I. This definition generalizes the definition of intervals of real numbers. When there is possible confusion with convex sets of geometry, one uses order-convex instead of "convex".

A convex sublattice of a lattice L is a sublattice of L that is also a convex set of L. Every nonempty convex sublattice can be uniquely represented as the intersection of a filter and an ideal of L.

An interval in a poset P is a subset that can be defined with interval notation:

- For a ≤ b, the closed interval [a, b] is the set of elements x satisfying a ≤ x ≤ b (that is, a ≤ x and x ≤ b). It contains at least the elements a and b.

- Using the corresponding strict relation "<", the open interval (a, b) is the set of elements x satisfying a < x < b (i.e. a < x and x < b). An open interval may be empty even if a < b. For example, the open interval (0, 1) on the integers is empty since there is no integer x such that 0 < x < 1.

- The half-open intervals [a, b) and (a, b] are defined similarly.

Whenever a ≤ b does not hold, all these intervals are empty. Every interval is a convex set, but the converse does not hold; for example, in the poset of divisors of 120, ordered by divisibility (see Fig. 7b), the set {1, 2, 4, 5, 8} is convex, but not an interval.

An interval I is bounded if there exist elements such that I ⊆ [a, b]. Every interval that can be represented in interval notation is obviously bounded, but the converse is not true. For example, let P = (0, 1) ∪ (1, 2) ∪ (2, 3) as a subposet of the real numbers. The subset (1, 2) is a bounded interval, but it has no infimum or supremum in P, so it cannot be written in interval notation using elements of P.

A poset is called locally finite if every bounded interval is finite. For example, the integers are locally finite under their natural ordering. The lexicographical order on the cartesian product is not locally finite, since (1, 2) ≤ (1, 3) ≤ (1, 4) ≤ (1, 5) ≤ ... ≤ (2, 1). Using the interval notation, the property "a is covered by b" can be rephrased equivalently as

This concept of an interval in a partial order should not be confused with the particular class of partial orders known as the interval orders.

See also

[edit]- Antimatroid, a formalization of orderings on a set that allows more general families of orderings than posets

- Causal set, a poset-based approach to quantum gravity

- Comparability graph – Graph linking pairs of comparable elements in a partial order

- Complete partial order – Mathematical phrase

- Directed set – Mathematical ordering with upper bounds

- Graded poset

- Incidence algebra – Associative algebra used in combinatorics

- Lattice – Set whose pairs have minima and maxima

- Locally finite poset

- Möbius function on posets – Associative algebra used in combinatorics

- Nested set collection

- Order polytope

- Ordered field – Algebraic object with an ordered structure

- Ordered group – Group with a compatible partial order

- Ordered vector space – Vector space with a partial order

- Poset topology, a kind of topological space that can be defined from any poset

- Scott continuity – continuity of a function between two partial orders.

- Semilattice – Partial order with joins

- Semiorder – Numerical ordering with a margin of error

- Szpilrajn extension theorem – every partial order is contained in some total order.

- Stochastic dominance – Partial order between random variables

- Strict weak ordering – strict partial order "<" in which the relation "neither a < b nor b < a" is transitive.

- Total order – Order whose elements are all comparable

- Zorn's lemma – Mathematical proposition equivalent to the axiom of choice

Notes

[edit]- ^ A proof can be found here.

- ^ which always exists and is unique, since is assumed to be finite

- ^ See General relativity § Time travel.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Wallis, W. D. (14 March 2013). A Beginner's Guide to Discrete Mathematics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4757-3826-1.

- ^ Simovici, Dan A. & Djeraba, Chabane (2008). "Partially Ordered Sets". Mathematical Tools for Data Mining: Set Theory, Partial Orders, Combinatorics. Springer. ISBN 9781848002012.

- ^ Flaška, V.; Ježek, J.; Kepka, T.; Kortelainen, J. (2007). "Transitive Closures of Binary Relations I". Acta Universitatis Carolinae. Mathematica et Physica. 48 (1). Prague: School of Mathematics – Physics Charles University: 55–69. Lemma 1.1 (iv). This source refers to asymmetric relations as "strictly antisymmetric".

- ^ Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Avigad, Jeremy; Lewis, Robert Y.; van Doorn, Floris (29 March 2021). "13.2. More on Orderings". Logic and Proof (Release 3.18.4 ed.). Archived from the original on 3 April 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

So we can think of every partial order as really being a pair, consisting of a weak partial order and an associated strict one.

- ^ Rounds, William C. (7 March 2002). "Lectures slides" (PDF). EECS 203: DISCRETE MATHEMATICS. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Kwong, Harris (25 April 2018). "7.4: Partial and Total Ordering". A Spiral Workbook for Discrete Mathematics. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ "Finite posets". Sage 9.2.beta2 Reference Manual: Combinatorics. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

compare_elements(x, y): Compare x and y in the poset. If x < y, return −1. If x = y, return 0. If x > y, return 1. If x and y are not comparable, return None.

- ^ Chen, Peter; Ding, Guoli; Seiden, Steve. On Poset Merging (PDF) (Technical report). p. 2. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

A comparison between two elements s, t in S returns one of three distinct values, namely s≤t, s>t or s|t.

- ^ Prevosto, Virgile; Jaume, Mathieu (11 September 2003). Making proofs in a hierarchy of mathematical structures. CALCULEMUS-2003 – 11th Symposium on the Integration of Symbolic Computation and Mechanized Reasoning. Roma, Italy: Aracne. pp. 89–100.

- ^ Merrifield, Richard E.; Simmons, Howard E. (1989). Topological Methods in Chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 28. ISBN 0-471-83817-9. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

A partially ordered set is conveniently represented by a Hasse diagram...

- ^ Neggers, J.; Kim, Hee Sik (1998), "4.2 Product Order and Lexicographic Order", Basic Posets, World Scientific, pp. 62–63, ISBN 9789810235895

- ^ Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 17–18.

- ^ P. R. Halmos (1974). Naive Set Theory. Springer. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4757-1645-0.

- ^ Davey & Priestley (2002), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Jech, Thomas (2008) [1973]. The Axiom of Choice. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-46624-8.

- ^ Ward, L. E. Jr (1954). "Partially Ordered Topological Spaces". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 5 (1): 144–161. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1954-0063016-5. hdl:10338.dmlcz/101379.

References

[edit]- Davey, B. A.; Priestley, H. A. (2002). Introduction to Lattices and Order (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78451-1.

- Deshpande, Jayant V. (1968). "On Continuity of a Partial Order". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 19 (2): 383–386. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1968-0236071-7.

- Schmidt, Gunther (2010). Relational Mathematics. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications. Vol. 132. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76268-7.

- Bernd Schröder (11 May 2016). Ordered Sets: An Introduction with Connections from Combinatorics to Topology. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-319-29788-0.

- Stanley, Richard P. (1997). Enumerative Combinatorics 1. Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics. Vol. 49. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-66351-2.

- Eilenberg, S. (2016). Foundations of Algebraic Topology. Princeton University Press.

- Kalmbach, G. (1976). "Extension of Homology Theory to Partially Ordered Sets". J. Reine Angew. Math. 280: 134–156.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Hasse diagrams at Wikimedia Commons; each of which shows an example for a partial order

Media related to Hasse diagrams at Wikimedia Commons; each of which shows an example for a partial order

Partially ordered set

View on GrokipediaFundamental Definitions

Partial orders

A partial order is a binary relation on a set that generalizes the intuitive notion of ordering, allowing for cases where some elements are incomparable, unlike total orders where every pair of elements is comparable. This structure arises naturally in mathematics and computer science, modeling hierarchies such as subset inclusion or task dependencies. Formally, a partial order on a set is a binary relation that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive. Reflexivity requires that for every , . Antisymmetry ensures that if and , then . Transitivity means that if and , then . These properties together capture the essence of an ordering while permitting incomparability. The term "partly ordered set" was introduced by Garrett Birkhoff in his 1940 monograph Lattice Theory, where he also suggested the abbreviation "poset."[10] This is now commonly referred to as a "partial order," formalizing structures central to lattice theory. To state this rigorously, consider a set and relation . The partial order axioms are: for all ,- Reflexivity: ,

- Antisymmetry: and imply ,

- Transitivity: and imply .

Strict partial orders

A strict partial order on a set is a binary relation that is irreflexive (for all , ) and transitive (for all , if and , then ).[11] This formulation distinguishes strict partial orders from non-strict partial orders, which include reflexivity.[12] Equivalently, a strict partial order can be defined as a transitive and asymmetric relation, where asymmetry means that if , then .[11] Asymmetry follows from irreflexivity and transitivity: suppose and ; then by transitivity, , contradicting irreflexivity.[12] In a strict partial order, two elements are comparable if or ; otherwise, they are incomparable.[11]Relation between non-strict and strict partial orders

Given a non-strict partial order on a set , the corresponding strict partial order is defined by if and only if and .[13] This construction removes the reflexive pairs from the relation , yielding an irreflexive relation.[13] Formally, the strict order can be expressed as .[13] Conversely, given a strict partial order on , the corresponding non-strict partial order is obtained by adding reflexivity, defining if and only if or .[13] This is known as the reflexive closure of the strict order.[14] These conversions establish a bijection between the set of all non-strict partial orders and the set of all strict partial orders on a given set .[14] Every strict partial order arises uniquely from a non-strict one via the first construction, and every non-strict partial order arises uniquely from a strict one via the second, with the two processes being mutual inverses.[13][15] To verify this correspondence, first suppose is a non-strict partial order (reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive). The derived is irreflexive because for all , since but .[13] It is asymmetric (hence antisymmetric) because if and , then , (so by antisymmetry of ), contradicting .[13] Transitivity holds: if and , then with and , so and (since is antisymmetric), yielding .[13] For the reverse direction, suppose is a strict partial order (irreflexive, asymmetric, and transitive). The derived is reflexive by construction ().[14] Antisymmetry follows: if and , then either or , but and contradicts asymmetry, so .[13] Transitivity holds: if and , the cases (equality or strict) combine via transitivity of and reflexivity to yield .[13] Applying the conversions in either order recovers the original relation, confirming the bijection.[14]Dual orders

In order theory, given a partially ordered set , the dual order (also known as the converse or opposite order) is the binary relation on defined by if and only if for all .[16] This reversal preserves the structure of the partial order: reflexivity holds because since ; antisymmetry follows as and imply and , hence ; and transitivity is satisfied because if and , then and , so or .[16] Thus, if is a partial order on , then is also a partial order on the same set. For the associated strict partial order (defined as if and ), the dual strict order is given by if and only if .[16] This strict dual inherits irreflexivity and transitivity from the original strict order by the same symmetry arguments, ensuring it remains a strict partial order.[16] A concrete example arises in total orders, where the dual provides a complete reversal. Consider the set of natural numbers under the standard order , which is a total order. The dual order reverses this to the descending order, where if and only if in the usual sense (e.g., because ). This duality highlights the symmetry in order structures and is fundamental in proving theorems via the principle of duality, where statements about partial orders have corresponding dual statements that hold equivalently.Notation and Visualizations

Symbolic notation

In mathematical literature, a partially ordered set, or poset, is conventionally denoted by an ordered pair , where is the underlying set and is the binary relation representing the non-strict partial order on .[1] The symbol is the standard for the non-strict partial order, satisfying reflexivity, antisymmetry, and transitivity, while the corresponding strict partial order—obtained by excluding equality—is typically denoted by .[17] Alternative symbols include or for the non-strict case and or for the strict case, often employed in specialized fields like domain theory or to distinguish the order from numerical inequalities or set inclusions.[18] For instance, may be used when the standard risks ambiguity with the order on real numbers. The relation can be expressed in infix notation as (or ), which is prevalent for readability, or in prefix (functional) notation as , treating the order as a binary operation on elements.[19] The infix form aligns with intuitive comparisons and is preferred in most contemporary texts, while prefix notation appears in formal or computational contexts.[17] Authors are advised to specify the relation explicitly in contexts where might be conflated with numerical ordering or subset inclusion, such as by qualifying it as "the partial order on ".Hasse diagrams

A Hasse diagram provides a graphical representation of a finite partially ordered set (poset) , where each element of is represented by a vertex (point), and a directed edge connects vertices and if covers , meaning and there exists no such that .[5] This covering relation captures the immediate successors in the order, omitting self-loops due to reflexivity ( is not shown as an edge) or edges that would arise from transitivity (no indirect connections are drawn).[5] The result is the transitive reduction of the poset's comparability graph, emphasizing the minimal relations needed to reconstruct the full order.[20] To construct a Hasse diagram, vertices are positioned in the plane such that if , then the vertex for lies strictly below that for , often grouped into horizontal levels based on a rank or height function (the length of the longest chain below the element).[5] Edges are drawn as line segments connecting covering pairs, directed upward but typically without arrowheads to simplify the drawing, as the orientation is implied by position.[20] Vertex labels can be omitted when the elements are unambiguous in context, and the layout strives to minimize edge crossings for clarity, though this is not always possible in non-planar posets.[5] Hasse diagrams are particularly advantageous for visualizing finite posets, offering a compact depiction that avoids clutter from redundant edges while preserving the order's structure.[5] They facilitate the identification of key features, such as chains (paths in the diagram) and antichains (sets of incomparable elements often appearing at the same level), aiding in the analysis of the poset's width and height.[5] A representative example is the Hasse diagram of the Boolean lattice , consisting of all subsets of a 3-element set ordered by inclusion. The bottom vertex represents the empty set , connected upward to three singletons at the next level; each singleton connects to two doubletons (e.g., to and ), forming a middle level of three doubletons; and all doubletons connect to the top vertex, the full set . This layered structure highlights the poset's symmetry and graded ranks, with each level corresponding to the cardinality of the subsets.[5]Equivalent Formulations

Axiomatic definitions

A partial order on a set is a binary relation that satisfies three fundamental axioms: reflexivity, antisymmetry, and transitivity. Reflexivity requires that every element is related to itself: for all , . Antisymmetry ensures that if two distinct elements are mutually related, they must be equal: for all , if and , then . Transitivity guarantees that the relation chains appropriately: for all , if and , then . These axioms together characterize a partial order as a reflexive, transitive, and antisymmetric binary relation on the set. In some formulations, reflexivity is sometimes omitted when considering broader classes of relations, leading to quasi-orders (also known as preorders), which are merely reflexive and transitive; however, antisymmetry remains essential to distinguish partial orders from quasi-orders. To verify these axioms for a small finite set, one can represent the relation as a matrix and check the properties directly; for example, consider a set with possible reflexive relations.| Relation Matrix | Reflexive? | Antisymmetric? | Transitive? | Partial Order? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (equality) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| () | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| (universal) | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| () | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Closure operator characterizations

A closure operator on a partially ordered set is a function satisfying the following conditions for all :- Extensivity: ,

- Idempotency: ,

- Monotonicity: implies .

Illustrative Examples

Basic posets

A partially ordered set, or poset, is a set equipped with a binary relation that is reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive.[24] These axioms ensure that the relation captures a notion of "order" without requiring full comparability between elements. Basic examples illustrate how posets range from highly structured to minimally ordered structures, helping to distinguish partial orders from other relations. The simplest poset is the trivial poset consisting of a singleton set, such as {a}, with the only relation being the reflexive a \leq a.[25] In this case, antisymmetry and transitivity hold vacuously, as there are no distinct elements to compare. A discrete poset on a finite set of n elements, such as {1, 2, \dots, n}, uses only the reflexive relation, making all distinct elements incomparable.[26] This structure satisfies the poset axioms but exhibits no ordering beyond reflexivity, serving as an extreme case of partiality. The natural numbers \mathbb{N} under the standard less-than-or-equal relation \leq form a total order, a special type of poset where every pair of elements is comparable.[3] For instance, 1 \leq 2 \leq 3, and this extends indefinitely without incomparability. The positive integers under the divisibility relation |, where m | n if n is a multiple of m, provide a classic partial order.[27] Here, 1 | 2 | 4 and 1 | 3 | 6, but 2 and 3 are incomparable since neither divides the other, demonstrating partiality beyond a total order. In contrast, an equivalence relation, such as congruence modulo n on the integers, fails to be a partial order because it is symmetric, violating antisymmetry—for example, if a \equiv b \pmod{n} and b \equiv a \pmod{n} with a \neq b, then a \leq b and b \leq a but a \not= b.[28]Product and sum constructions

Given two partially ordered sets and , the product order on the Cartesian product is defined by if and only if and .[29] This componentwise ordering inherits reflexivity, antisymmetry, and transitivity from the orders on and , ensuring that is itself a partially ordered set.[30] A representative example is the product , where denotes the natural numbers under the usual order . Here, elements like and are incomparable, since neither and nor the reverse holds simultaneously, forming a grid-like poset structure.[29] For combining multiple posets, the ordinal sum (or linear sum) of a sequence of posets , where is a chain under some total order, is constructed on the disjoint union by declaring all elements of less than all elements of whenever in , while preserving the internal orders within each . This yields a poset that concatenates the components in the order of the index chain, useful for building linear extensions from chains of basic posets like singletons or antichains.[29] A variant on the product is the lexicographic order on , defined by if or ( and ), prioritizing the first component.[30] This strict preference in the first coordinate produces a partial order that remains partial unless both and are chains, contrasting with the balanced componentwise comparison of the standard product.[29] These constructions preserve the partial nature of the original orders: the product order maintains incomparabilities across components, while the ordinal sum extends comparability linearly along the index chain, facilitating the formation of total orders from partial ones in specific cases.[30]Key Derived Concepts

Chains and antichains

A chain in a partially ordered set (poset) is a subset such that every pair of elements in is comparable, meaning for any , either or . This induces a total order on . Dually, an antichain in is a subset in which no two distinct elements are comparable, so for any distinct , neither nor . For example, consider the poset of positive integers under divisibility, where if divides . The subset forms a chain since divides and divides , while is an antichain as no one divides another. The height of a poset is defined as the cardinality of its largest chain, and the width is the cardinality of its largest antichain.[31] By Zorn's lemma, every poset admits maximal chains (chains not properly contained in any larger chain), and the poset is the union of its maximal chains, since every element lies in some maximal chain. Mirsky's theorem states that in any finite poset, the height equals the minimum number of antichains whose union covers the poset.Order ideals and filters

In the context of a partially ordered set , an order ideal, also known as a down-set, is a subset such that for all and with , it holds that .[32] This property ensures that order ideals are closed under downward extension with respect to the partial order. A principal order ideal generated by an element is denoted , which consists of all elements less than or equal to .[32] Every principal order ideal is an order ideal, and in finite posets, every order ideal is a finite union of principal order ideals.[33] Dually, an order filter, or up-set, is a subset such that for all and with , it follows that .[32] The principal order filter generated by is , capturing all elements greater than or equal to . Order filters in correspond precisely to order ideals in the dual poset , where the order is reversed, highlighting the symmetric roles of these structures in order theory.[32] The collection of all order ideals of , denoted , forms a poset under inclusion, which is itself a distributive lattice known as the ideal lattice of .[33] Order ideals and filters play a fundamental role in completions of posets; for instance, the Dedekind–MacNeille completion embeds into a complete lattice constructed using intersections of principal filters and unions of principal ideals.[32]Extrema and heights

In a partially ordered set , an element is called a maximal element if there exists no such that , meaning that if , then . Dually, an element is a minimal element if there exists no such that , or equivalently, if implies . These concepts capture elements that cannot be extended further upward or downward in the order, respectively, but a poset may contain multiple maximal or minimal elements, or none at all, depending on its structure. A greatest element (or maximum) of is an element such that for every ; if it exists, it is the unique maximal element, as it dominates all others. Similarly, a least element (or minimum) is an element such that for every , and it would be the unique minimal element. However, not every poset possesses a greatest or least element; for instance, consider the poset consisting of two distinct incomparable elements under the discrete order (an antichain), where each element is both maximal and minimal, but neither serves as a greatest or least element since no single element is comparable to the other in the required direction. The height of a poset , denoted , measures its "vertical" extent and is defined as the cardinality of a longest chain in .[31] Thus, equals the supremum over all chains of their sizes, providing a quantitative sense of the poset's depth; for example, the Boolean lattice on elements has height , corresponding to its longest chain of elements.[34] In a graded poset, a rank function assigns to each element a non-negative integer rank such that minimal elements have rank 0, and if covers (i.e., with no element between), then ; the height is then the maximum value of plus one.[35] A fundamental result connecting extrema to infinite posets is Zorn's lemma, which states that if every chain in a partially ordered set has an upper bound in , then contains at least one maximal element; this holds under the axiom of choice, particularly for non-finite posets where direct construction may fail.[36] For instance, the power set of an infinite set ordered by inclusion satisfies the upper bound condition for chains (unions serve as bounds) and thus admits maximal elements, such as maximal ideals in certain algebraic structures.[37]Order-Preserving Maps

Monotone functions

In order theory, a monotone function (also called an order-preserving or isotone map) between two partially ordered sets and is a function such that for all , if then . This condition ensures that the function respects the partial order, mapping ordered pairs to ordered pairs without reversing the direction. A strict monotone function strengthens this by requiring that (where denotes the strict partial order, i.e., and ) implies . An antitone function, conversely, is order-reversing: implies , where is the reverse of .[38] The composition of two antitone functions yields a monotone function, as the reversals cancel out.[38] Monotone functions preserve comparability: if and are comparable in , then and are comparable in with the order direction maintained. However, they do not preserve incomparability, as incomparable elements in may map to comparable elements in . Constant functions are always monotone, since for any , the images satisfy by reflexivity. A standard example is the inclusion map from a subposet of to , which is monotone because the order restricted to agrees with the order on .Lattice homomorphisms

A lattice homomorphism is a function between two lattices and that preserves both the join and meet operations, meaning that for all elements , This preservation ensures that the structure of joins and meets is maintained under the mapping.[39][40] Such homomorphisms are automatically monotone functions, as the order relation in a lattice can be recovered from the joins and meets: if in , then and , so and , implying in . Consequently, lattice homomorphisms preserve the partial order while additionally respecting the lattice operations.[39] In the case of bounded lattices, where and possess top and bottom elements (denoted and , respectively), a lattice homomorphism maps these bounds to elements that act as bounds for the image of : specifically, is a bottom element for , and is a top element for . If is surjective, then and ; in general, the preservation holds within the sublattice generated by the image.[39][41] A concrete example arises with power set lattices: given sets , the inclusion map defined by for is a lattice homomorphism, since it preserves unions () and intersections (), where denotes the power set of ordered by inclusion, with joins as unions and meets as intersections. This map embeds the lattice structure of subsets of into that of .[42][43] Lattice homomorphisms apply specifically to lattices, which are posets where every pair of elements has a join and a meet; not all partially ordered sets possess this structure, so the concept is restricted to those that do.[40]Extensions and Substructures

Linear extensions

A linear extension of a partially ordered set is a total order on the underlying set such that implies for all .[44] This preserves all existing comparabilities while rendering every pair of elements comparable. Equivalently, a linear extension corresponds to an order-preserving embedding of as a subposet into a chain, via a monotone injection that maintains the original order relations.[45] The existence of at least one linear extension for any poset is guaranteed by Szpilrajn's theorem, which states that every partial order can be extended to a total order on the same set.[46] Standard proofs of this theorem rely on Zorn's lemma or the well-ordering theorem, both equivalent to the axiom of choice. Without the axiom of choice, there exist models of ZF set theory in which some posets lack linear extensions.[47] Linear extensions find key applications in computer science, particularly in sorting algorithms. In the context of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), where the partial order arises from the transitive closure of the edge relation, a topological sort produces a linear extension that respects all precedence constraints.[48] This is essential for tasks like scheduling dependencies or resolving build orders in software systems. Computationally, linear extensions of finite posets can be constructed via greedy algorithms that iteratively select minimal elements, though efficient methods vary with the poset's structure.[49]Subposets and induced orders

In a partially ordered set , a subposet is obtained by taking a subset and equipping it with the induced partial order , defined such that if and only if in , for all .[6] This construction preserves the order relations between elements of exactly as they appear in the original poset, ensuring that is itself a partially ordered set.[50] A special type of subposet is the convex subposet, which is closed under intervals in the order. Specifically, a subposet of is convex if, whenever and there exists such that , then .[51] Equivalently, convex subposets are those that contain all elements between any two of their members in the original order, making them "interval-closed" subsets.[52] This property is useful in studying connected components or embeddings where intermediate elements cannot be omitted without altering the structure. Order ideals, also called down-sets, form another important class of subposets that are downward-closed: if and with , then .[53] These are induced subposets by definition and play a key role in decomposing posets, though their full structure is explored elsewhere. Subposets inherit core properties from the ambient poset but may lose or alter others. For instance, if is a chain (total order), every induced subposet remains a chain, as the order on is total.[6] However, more complex posets may yield subposets that fail to preserve lattice properties, such as the existence of meets or joins, if key elements are excluded. As an example, consider the finite total order ; removing the maximum element to form yields an induced subposet that is still a chain but shorter, illustrating how subposets can truncate structures while retaining the induced order.[50]Combinatorial Aspects

Enumerating partial orders

The enumeration of partial orders on finite sets is a central problem in order theory and combinatorics. For a finite set with labeled elements, the number of distinct partial orders is given by the sequence where there is 1 poset for and , 3 for , 19 for , 219 for , and 4231 for , with values computed up to using algorithmic methods.[54] These counts represent the number of reflexive, antisymmetric, and transitive binary relations on the labeled set, equivalent to the number of labeled acyclic transitive directed graphs. For unlabeled elements, where posets are considered up to isomorphism, the sequence begins with 1 for and , 2 for , 5 for , 16 for , and 63 for , with enumerations available up to larger but requiring more computational effort due to symmetry considerations.[55] A notable special case in poset enumeration involves the Boolean lattice , the power set of an -element set ordered by inclusion. The Dedekind number counts the number of antichains in this poset, equivalently the number of monotone Boolean functions on variables or the number of down-sets (order ideals). These numbers grow super-exponentially, reflecting the combinatorial complexity of subset structures preserving monotonicity. Known values include , , , , , , , , and , with computed in 2023 using advanced algorithmic techniques involving matrix multiplication over finite fields.[56] Exact computation of remains challenging for as of 2025, with asymptotic bounds established but no closed-form formula known; lower and upper estimates suggest growth on the order of .[57] The asymptotic behavior of the total number of labeled posets on elements is , derived by showing that nearly all such posets consist of three graded levels with specific incomparability patterns.[58] This super-exponential growth underscores the difficulty of exhaustive enumeration beyond small , though recursive constructions and probabilistic methods provide tight bounds. Historically, foundational advances in poset enumeration trace to Gian-Carlo Rota's 1964 development of the Möbius function for partially ordered sets, which enabled inclusion-exclusion principles and generating function approaches for counting structures within posets.[59]| Labeled posets | Unlabeled posets | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 19 | 5 |

| 4 | 219 | 16 |

| 5 | 4231 | 63 |

| Dedekind number | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 |

| 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 20 |

| 4 | 168 |

| 5 | 7581 |

![{\displaystyle P^{*}=P[X^{*}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b4739d74d3a23e9ce9c7645030240cd78b43ab7d)

![{\displaystyle [a,b]=\{a,b\}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c22504982538e7e532e76ad1ebfafd8abd6bb8f2)