Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

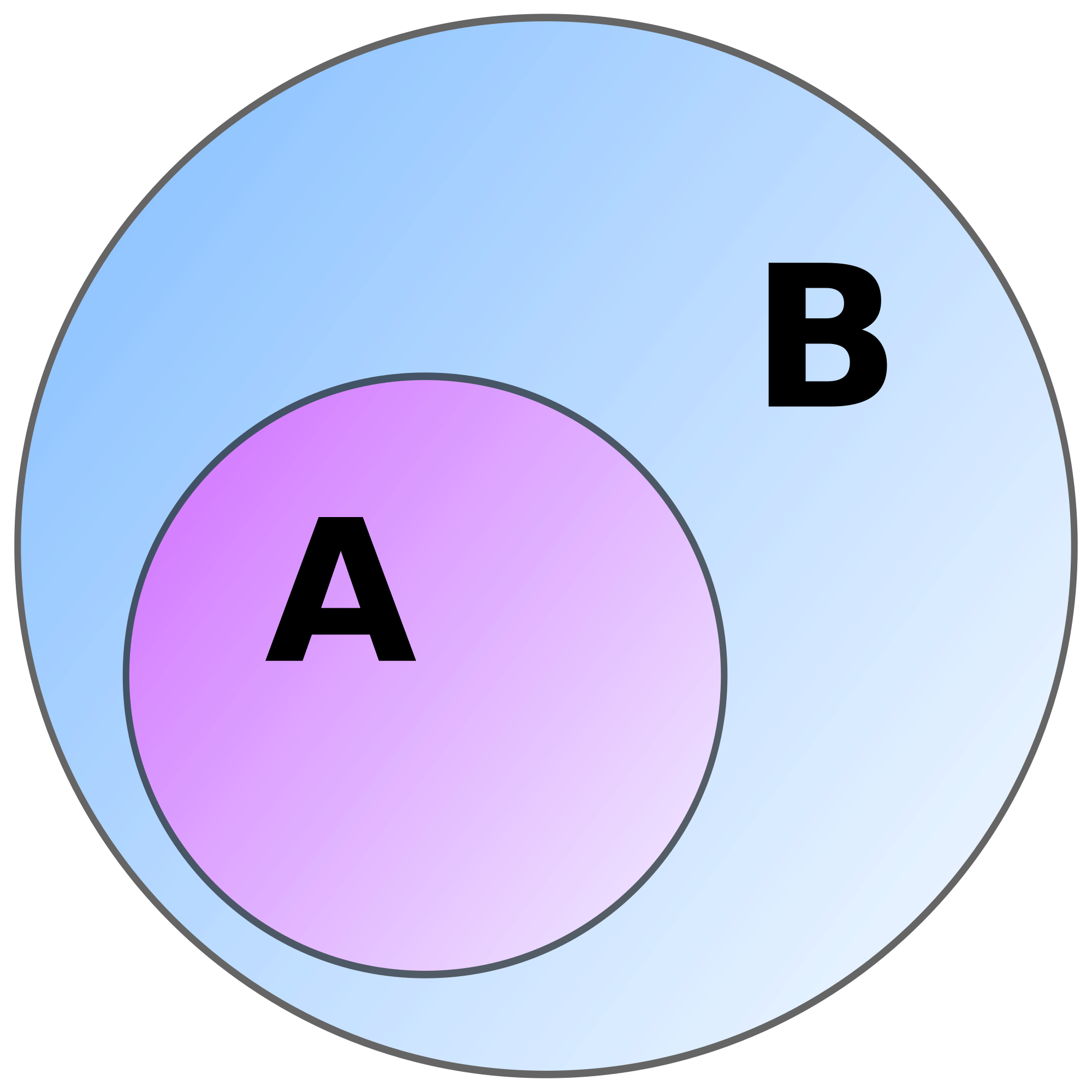

Subset

View on Wikipedia

A is a subset of B (denoted ) and, conversely, B is a superset of A (denoted )

In mathematics, a set A is a subset of a set B if all elements of A are also elements of B; B is then a superset of A. It is possible for A and B to be equal; if they are unequal, then A is a proper subset of B. The relationship of one set being a subset of another is called inclusion (or sometimes containment). A is a subset of B may also be expressed as B includes (or contains) A or A is included (or contained) in B. A k-subset is a subset with k elements.

When quantified, is represented as [1]

One can prove the statement by applying a proof technique known as the element argument[2]:

Let sets A and B be given. To prove that

- suppose that a is a particular but arbitrarily chosen element of A

- show that a is an element of B.

The validity of this technique can be seen as a consequence of universal generalization: the technique shows for an arbitrarily chosen element c. Universal generalisation then implies which is equivalent to as stated above.

Definition

[edit]If A and B are sets and every element of A is also an element of B, then:

- A is a subset of B, denoted by , or equivalently,

- B is a superset of A, denoted by

If A is a subset of B, but A is not equal to B (i.e. there exists at least one element of B which is not an element of A), then:

- A is a proper (or strict) subset of B, denoted by , or equivalently,

- B is a proper (or strict) superset of A, denoted by

The empty set, written or has no elements, and therefore is vacuously a subset of any set X.

Basic properties

[edit]

- Reflexivity: Given any set , [3]

- Transitivity: If and , then

- Antisymmetry: If and , then .

Proper subset

[edit]- Irreflexivity: Given any set , is False.

- Transitivity: If and , then

- Asymmetry: If then is False.

⊂ and ⊃ symbols

[edit]Some authors use the symbols and to indicate subset and superset respectively; that is, with the same meaning as and instead of the symbols and .[4] For example, for these authors, it is true of every set A that (a reflexive relation).

Other authors prefer to use the symbols and to indicate proper (also called strict) subset and proper superset respectively; that is, with the same meaning as and instead of the symbols and [5] This usage makes and analogous to the inequality symbols and For example, if then x may or may not equal y, but if then x definitely does not equal y, and is less than y (an irreflexive relation). Similarly, using the convention that is proper subset, if then A may or may not equal B, but if then A definitely does not equal B.

Examples of subsets

[edit]

- The set A = {1, 2} is a proper subset of B = {1, 2, 3}, thus both expressions and are true.

- The set D = {1, 2, 3} is a subset (but not a proper subset) of E = {1, 2, 3}, thus is true, and is not true (false).

- The set {x: x is a prime number greater than 10} is a proper subset of {x: x is an odd number greater than 10}

- The set of natural numbers is a proper subset of the set of rational numbers; likewise, the set of points in a line segment is a proper subset of the set of points in a line. These are two examples in which both the subset and the whole set are infinite, and the subset has the same cardinality (the concept that corresponds to size, that is, the number of elements, of a finite set) as the whole; such cases can run counter to one's initial intuition.

- The set of rational numbers is a proper subset of the set of real numbers. In this example, both sets are infinite, but the latter set has a larger cardinality (or power) than the former set.

Another example in an Euler diagram:

-

A is a proper subset of B.

-

C is a subset but not a proper subset of B.

Power set

[edit]The set of all subsets of is called its power set, and is denoted by .[6]

The inclusion relation is a partial order on the set defined by . We may also partially order by reverse set inclusion by defining

For the power set of a set S, the inclusion partial order is—up to an order isomorphism—the Cartesian product of (the cardinality of S) copies of the partial order on for which This can be illustrated by enumerating , and associating with each subset (i.e., each element of ) the k-tuple from of which the ith coordinate is 1 if and only if is a member of T.

The set of all -subsets of is denoted by , in analogue with the notation for binomial coefficients, which count the number of -subsets of an -element set. In set theory, the notation is also common, especially when is a transfinite cardinal number.

Other properties of inclusion

[edit]- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their intersection is equal to A. Formally:

- A set A is a subset of B if and only if their union is equal to B. Formally:

- A finite set A is a subset of B, if and only if the cardinality of their intersection is equal to the cardinality of A. Formally:

- The subset relation defines a partial order on sets. In fact, the subsets of a given set form a Boolean algebra under the subset relation, in which the join and meet are given by intersection and union, and the subset relation itself is the Boolean inclusion relation.

- Inclusion is the canonical partial order, in the sense that every partially ordered set is isomorphic to some collection of sets ordered by inclusion. The ordinal numbers are a simple example: if each ordinal n is identified with the set of all ordinals less than or equal to n, then if and only if

See also

[edit]- Convex subset – In geometry, set whose intersection with every line is a single line segment

- Inclusion order – Partial order that arises as the subset-inclusion relation on some collection of objects

- Mereology – Study of parts and the wholes they form

- Region – Connected open subset of a topological space

- Subset sum problem – Decision problem in computer science

- Subsumptive containment – System of elements that are subordinated to each other

- Subspace – Mathematical set with some added structure

- Total subset – Subset T of a topological vector space X where the linear span of T is a dense subset of X

References

[edit]- ^ Rosen, Kenneth H. (2012). Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-07-338309-5.

- ^ Epp, Susanna S. (2011). Discrete Mathematics with Applications (Fourth ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- ^ Stoll, Robert R. (1963). Set Theory and Logic. San Francisco, CA: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-63829-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Rudin, Walter (1987), Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.), New York: McGraw-Hill, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1, MR 0924157

- ^ Subsets and Proper Subsets (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-23, retrieved 2012-09-07

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Subset". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2020-08-23.

Bibliography

[edit]- Jech, Thomas (2002). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-44085-2.

External links

[edit] Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Subsets at Wikimedia Commons- Weisstein, Eric W. "Subset". MathWorld.

![{\displaystyle [A]^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0fe283baada639c7008fb3a8612464d214ee1e5d)

![{\displaystyle [n]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a26847bfc29bbeb4d6ef62ac3fd076378c0fd1db)

![{\displaystyle [a]\subseteq [b].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/86c0b0cba950301eacc0a11b017b876d2460a33f)