Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Patpong

View on WikipediaPatpong (Thai: พัฒน์พงศ์, RTGS: Phat Phong, pronounced [pʰát pʰōŋ]) is an entertainment district in Bangkok's Bang Rak District, Thailand, catering mainly, though not exclusively, to foreign tourists and expatriates.[1] Patpong is internationally known as a red light district at the heart of Bangkok's sex industry.[1] It is the smallest and oldest of several red-light districts in the city.[2] Some of Bangkok's red light districts cater primarily to Thai men while others, like Patpong, cater primarily to foreigners.[1]

Key Information

Since the early 1990s a busy night market aimed at tourists has also been located in Patpong.[2][3]

Location and layout

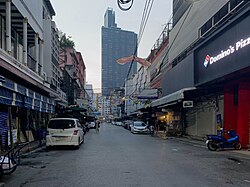

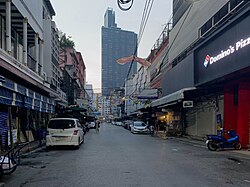

[edit]Patpong consists of two parallel side streets running between Silom and Surawong Roads[4] and one side street running from the opposite side of Surawong. Patpong is within walking distance from the BTS Skytrain Silom Line's Sala Daeng Station, and MRT Blue Line's Si Lom Station.

Patpong 1 is the main street with many bars of various kinds. Patpong 2 also has many similar bars. Next to these lies Soi Jaruwan, sometimes referred to as Patpong 3 but best known as Silom Soi 4. It has long catered to gay men, whilst nearby Soi Thaniya has expensive bars with Thai hostesses that cater almost exclusively to Japanese men.[citation needed]

History and ownership

[edit]Patpong gets its name from the family that owns much of the area's property. Luang Patpongpanich (or Patpongpanit), an immigrant from Hainan Island, China, purchased the area in 1946.[5] At that time it was an undeveloped plot of land on the outskirts of the city.[6] A small khlong (canal) and a teakwood house were the only features. The family built a road – now called Patpong 1 – and several shop buildings, which were rented out. Patpong 2 was added later, and both roads are private property and not city streets.[6] Patpong 3 and Soi Thaniya are not owned by the Patpongpanich family. The old teak house was demolished long ago and the khlong was filled in to make room for more shops. Originally Patpong was an ordinary business area, but the arrival of bars eventually drove out most of the other businesses.

By 1968, a handful of nightclubs existed in the area, and Patpong became an R&R (rest and recuperation) stop for US military officers serving in the Vietnam War,[6] although the main R&R area for GIs was along New Petchburi Road, nicknamed "The Golden Mile".[7] In its prime during the 1970s and 1980s, Patpong was the premier nightlife area in Bangkok for foreigners, and was famous for its sexually explicit shows. In the mid-1980s the sois hosted an annual Patpong Mardi Gras, which was a weekend street fair that raised money for Thai charities.[8] In the early-1990s, however, the Patpongpanich family turned the sidewalks of Patpong 1 Road into a night market, renting out spaces to street vendors.[9]

The consequence was that Patpong lost much of its vibrancy as a nightlife strip, becoming crowded with tourist shoppers who ignored the nightlife. Nana Plaza and Soi Cowboy drew away many of Patpong's thrill seekers. Patpong became a designated "entertainment zone" in 2004, along with Royal City Avenue (RCA) and portions of Ratchadapisek Road, where the largest commercial sex venues are found. This designation allows its bars to stay open until 02:00, instead of the 24:00 or 01:00 legal closing times enforced in other areas.[10]

In October 2019 the Patpong Museum opened in Patpong Soi 2, housing a collection of art, antiques and displays covering 70 years of Patpong's history. The privately owned museum was located on the 2nd floor of building 5 opposite Foodland supermarket and below Black Pagoda.[11] Patpong Museum closed as of May 2023.

In media

[edit]Many Western films have featured Patpong, including The Deer Hunter (1978).[12] The final part of the musical Miss Saigon (1989) is set in the Patpong bar scene.[citation needed]

In Swimming to Cambodia, Spalding Gray discussed the red light district of Patpong and its prostitutes, saying there wasn't much else to see in Bangkok save the Gold Buddha during the day and the whorehouses at night.

The song Welcome to Thailand from the 1987 studio album of the same name by the Thai rock band Carabao contains the lyrics: "Tom, Tom, where you go last night?... I love Meuang Thai. I like Patpong". The song complains that Farang tourists (Westerners) are often attracted to the sleazy side of Thailand (the sex tourism of Patpong and Pattaya).[13]

The movie Baraka features several shots of strippers in Patpong.[14]

The 1994 book Patpong Sisters: An American Woman's View of the Bangkok Sex World by Cleo Odzer describes the experiences of an anthropologist doing field research in Thailand.[15]

Patpong: Bangkok's Twilight Zone (2001, by Nick Nostitz) is a photographic depiction of aspects of the Patpong night life.[16]

The 2008 book Ladyboys: The Secret World of Thailand's Third Gender paints a portrait of Thailand's kathoeys.[17]

Patpong opera is a collection of songs written by Kevin Wood, manager of Radio City, to tunes of modern rock songs. Together they tell the story of the people in Patpong.[18]

Patpong serves as part of the setting in Tom Robbins' book Villa Incognito.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Patpong Opinion - including the ping pong scam!". Bangkok112. 19 December 2015. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ a b Weitzer, Ronald (2023). Sex Tourism in Thailand: Inside Asia’s Premier Erotic Playground. NYU Press. p. 114. ISBN 9781479813407.

- ^ "Bangkok Nightlife 2018 (UPDATED!)". Bangkok-Nightlife.com. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- ^ "Patpong in Bangkok - Bangkok Go Go Bars". bangkok.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Slow, Oliver (2020-10-30). "When the CIA Ran Covert Operations From Bangkok's Red-Light District". VICE. Retrieved 2024-09-06.

- ^ a b c "Patpong night market - the one amid the red light district". Experience Unique Bangkok. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Janssen, Peter (29 November 2019). "Patpong: the rise of Bangkok's most famous red light district charted at new museum, complete with mock-up bar room and 'X-rated' area". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "The Patpong Mardi Gras". UPI. 19 February 1983. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Michael Backman. The banana plantation turned sex zone, The Age, 2005-09-21

- ^ Itthipongmaetee, Chayanit (2018-02-13). "Why Bangkok's Fun is Ending at Midnight Again". Khaosod English. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "'Patpong Museum' opens in Bangkok's original soi of sex". Coconuts. 28 October 2019.

- ^ "7 Movie Locations in Bangkok - Bangkok.com Magazine". bangkok.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ "เวลคัมทูไทยแลนด์ Welcome to Thailand". carabaoinenglish.com. 26 July 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Patpong, Bangkok, a filming location from the film Baraka". www.barakasamsara.com. 3 November 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Odzer, Cleo (1994). Patpong Sisters: An American Woman's View of the Bangkok Sex World. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1559702812. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Nostitz, Nick (2001). Patpong: Bangkok's Twilight Zone. Westzone. ISBN 978-0953743827. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Aldous, Susan; Sereemongkonpol, Pornchai (2008). Ladyboys: The Secret World of Thailand's Third Gender. Maverick House. ISBN 9781905379484. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Wood, Kevin (9 October 2012). "Bangkok". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ Robbins, Tom (2014). Villa Incognito (in German). Rowohlt E-Book. ISBN 9783644039810.

External links

[edit] Media related to Patpong at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Patpong at Wikimedia Commons

Patpong

View on GrokipediaPatpong is a compact entertainment district in Bangkok's Bang Rak area, Thailand, bounded by Silom and Surawong Roads, distinguished by its daytime night market offering counterfeit merchandise and street food alongside its nighttime role as a pioneering red-light zone with go-go bars and explicit stage shows.[1][2]

Named for the Patpongpanich family—a Thai-Chinese clan that acquired the former banana plantation land in 1946 for approximately 800,000 baht—the site initially served business interests before transforming amid post-World War II development.[1][3]

By the late 1960s, influxes of U.S. servicemen seeking rest and recreation during the Vietnam War catalyzed its shift into Bangkok's first concentrated hub of bars, massage parlors, and erotic venues, peaking in the 1980s with over 100 establishments before competition from areas like Nana Plaza diminished its dominance.[1][4]

While sustaining tourism through affordable shopping and nightlife, Patpong embodies causal dynamics of sex tourism economics, including prostitution often linked to rural economic pressures and urban migration, alongside persistent issues like bar scams targeting foreigners and reports of underage involvement and trafficking in Thailand's broader industry.[5][6][7]

Geography and Layout

Location and Accessibility

Patpong is located in the Bang Rak district of central Bangkok, Thailand, within the broader Silom commercial area. The district comprises narrow sois, primarily Patpong Soi 1 and Patpong Soi 2, which run parallel between Silom Road to the east and Surawong Road to the west.[8][9] A third connecting alley links these from the Silom Road side, forming a compact grid of approximately 0.1 square kilometers focused on nightlife and retail.[8] The area benefits from excellent connectivity to Bangkok's public transit network. The BTS Skytrain's Sala Daeng station on the Silom Line provides direct access, with a short walk of under 500 meters westward along Silom Road to the Patpong entrances.[10][9] Complementing this, the MRT Blue Line's Si Lom station lies adjacent, offering underground rail links to other parts of the city, including interchanges at Sukhumvit for northern and eastern routes.[11] Taxis, tuk-tuks, and app-based services like Grab are readily available but subject to heavy traffic, particularly evenings when the district peaks in activity; fares from central hubs like Siam Square typically range 100-200 Thai baht depending on conditions.[9] Walking from nearby landmarks, such as Lumpini Park to the northeast (about 2 kilometers), is feasible for pedestrians via sidewalks along Rama IV Road.[12]