Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fibularis longus

View on Wikipedia| fibularis longus | |

|---|---|

Animation | |

Mucous sheaths of tendons around right ankle, lateral aspect. (Tendon-sheath of fibularis longus labeled as peronaeus longus at bottom center.) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | Proximal part of lateral surface of shaft of fibula[1] and head of fibula |

| Insertion | First metatarsal, medial cuneiform[1] |

| Artery | Fibular (peroneal) artery |

| Nerve | Superficial fibular nerve[1] |

| Actions | Plantarflexion, eversion, support arches[1] |

| Antagonist | Tibialis anterior muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus fibularis longus |

| TA98 | A04.7.02.041 |

| TA2 | 2652 |

| FMA | 22539 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

In human anatomy, the fibularis longus (also known as peroneus longus) is a superficial muscle in the lateral compartment of the leg. It acts to tilt the sole of the foot away from the midline of the body (eversion) and to extend the foot downward away from the body (plantar flexion) at the ankle.

The fibularis longus is the longest and most superficial of the three fibularis (peroneus) muscles. At its upper end, it is attached to the head of the fibula, and its "belly" runs down along most of this bone. The muscle becomes a tendon that wraps around and behind the lateral malleolus of the ankle, then continues under the foot to attach to the medial cuneiform and first metatarsal. It is supplied by the superficial fibular nerve.

Structure

[edit]The fibularis longus arises from the head and upper two-thirds of the lateral, or outward, surface of the fibula, from the deep surface of the fascia, and from the connective tissue between it and the muscles on the front and back of the leg. It occasionally is also connected by a few fibers from the lateral condyle of the tibia. Between the muscle's attachments to the head and body of the fibula, there is a gap through which the common fibular nerve passes to the front of the leg.[2]

The muscle ends in a long tendon, which runs behind the lateral malleolus of the ankle in a groove that it shares with the tendon of the fibularis brevis; the groove is converted into a canal by the superior fibular retinaculum, and the tendons in it are contained in a common mucous sheath.[2]

The tendon then extends forward at an angle across the lateral side of the foot, below the fibular trochlea and the tendon of the fibularis brevis, and under cover of the inferior fibular retinaculum.[2] It crosses the lateral side of the cuboid and then runs underneath the cuboid in a groove that is converted into a canal by the long plantar ligament. The tendon then crosses the sole of the foot at an angle and inserts into the lateral side of the base of the first metatarsal and the lateral side of the medial cuneiform.[2] Occasionally, it also sends a slip to the base of the second metatarsal.[2]

The tendon changes direction at two points: first, behind the lateral malleolus; second, on the cuboid bone. In both of these locations, the tendon is thickened. At the cuboid, a fibrocartilaginous sesamoid (sometimes a sesamoid bone) usually develops in the substance of the tendon.[2]

The fibularis longus muscle is supplied by the superficial fibular nerve, which arises from the fifth lumbar and first sacral roots of the spinal cord.[3]

Function

[edit]The fibularis longus, together with the fibularis brevis and the tibialis posterior, extend the foot downward away from the body at the ankle (plantar flexion). It opposes the tibialis anterior and the fibularis tertius, which pull the foot upward toward the body (dorsiflexion).[2]

The fibularis longus also tilts the sole of the foot away from the midline of the body (eversion). Because of the angle at which it crosses the sole of the foot, it plays an important role in maintaining the transverse arch of the foot.[2]

Together, the fibularis muscles help to steady the leg upon the foot, especially in standing on one leg.[2]

Nomenclature and etymology

[edit]Terminologia Anatomica designates "fibularis" as the preferred word over "peroneus.".[4]

The word "peroneus" comes from the Greek word "perone," meaning pin of a brooch or a buckle. In medical terminology, the word refers to being of or relating to the fibula or to the outer portion of the leg.

Additional images

[edit]-

Bones of the right leg, anterior surface

-

Left calcaneus, inferior surface

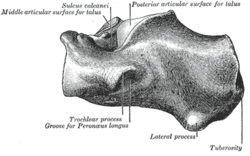

-

Left calcaneus, lateral surface

-

Coronal section through right talocrural and talocalcaneal joints

-

Fibularis (peroneus) longus labeled at right

-

Cross-section through middle of leg

-

The popliteal, posterior tibial, and fibular arteries

-

Deep nerves of the front of the leg

-

Back of left lower extremity

-

Lateral aspect of right leg

-

Muscles of leg (lateral view, deep dissection)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 486 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 486 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c d "Peroneus longus". Loyola University Chicago. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gray's Anatomy (1918), see infobox

- ^ Apaydin, Nihal; Bozkurt, Murat (2015-01-01), Tubbs, R. Shane; Rizk, Elias; Shoja, Mohammadali M.; Loukas, Marios (eds.), "Chapter 10 - Surgical Exposures for Nerves of the Lower Limb", Nerves and Nerve Injuries, San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 139–153, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802653-3.00059-2, ISBN 978-0-12-802653-3, retrieved 2021-02-21

- ^ FIPAT (2019). Terminologia Anatomica. Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology.