Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

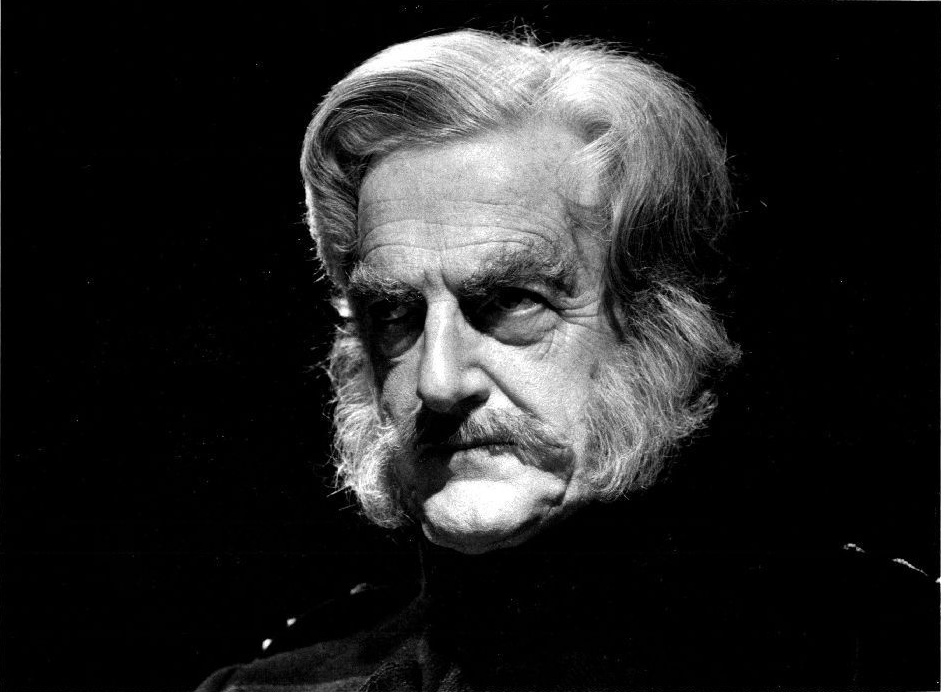

Peter Pears

View on Wikipedia

Sir Peter Neville Luard Pears CBE (/ˈpɪərz/ PEERZ; 22 June 1910 – 3 April 1986) was an English tenor. His career was closely associated with the composer Benjamin Britten, his personal and professional partner for nearly forty years.

Key Information

Pears' musical career started slowly. He was at first unsure whether to concentrate on playing piano and organ, or singing; it was not until he met Britten in 1937 that he threw himself wholeheartedly into singing. Once he and Britten were established as a partnership, the composer wrote many concert and operatic works with Pears's voice in mind, and the singer played roles in more than ten operas by Britten. In the concert hall, Pears and Britten were celebrated recitalists, known in particular for their performances of lieder by Schubert and Schumann. Together they recorded most of the works written for Pears by Britten, as well as a wide range of music by other composers. Working with other musicians, Pears sang an extensive repertoire of music from four centuries, from the Tudor period to the most modern times.

With Britten, Pears was a co-founder of the Aldeburgh Festival in 1947 and the Britten-Pears School in 1972. After Britten died in 1976, Pears remained an active participant in the festival and the school, where he was director of singing. His voice had a distinctive timbre, not to all tastes; however, critics recognised its uniqueness and ability to express atmosphere and nuance.

Life and career

[edit]Early years

[edit]Pears was born in Farnham, Surrey, the youngest of the seven children of Arthur Grant Pears and his wife, Jessie Elizabeth de Visme, daughter of Richard Luard.[1] Arthur Pears was a civil engineer and successful businessman, who spent much of his time working overseas. The biographers Christopher Headington and Donald Mitchell both remark on two contrasting strands in Pears's heredity: the Luard family was notable for its naval and military connections, and on his father's side there was a strong religious tradition, both Anglican and Quaker, with Elizabeth Fry counted among his ancestors.[2] Mitchell comments that Pears's lifelong pacifism stemmed from the Quaker side of the family, and adds, "There was indeed something of the patrician Quaker in his looks, manners, and deeds. His habitual charm and courtesy rarely deserted him."[3]

Although his father, and sometimes his mother, were absent abroad for long periods, Pears evidently had a happy childhood.[3] He enjoyed his schooldays at his prep school, The Grange, and his public school, Lancing College, which he attended from 1923 to 1928. He showed considerable talent for music, both as a pianist and as a singer, playing leading roles in school productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operas.[4] He was a capable and enthusiastic cricketer, and remembered all his life the pride he felt in scoring 81 not out in a trial match against Surrey at the Oval.[5] Lancing had a strong Christian tradition; while there, Pears felt a sense of vocation for the priesthood, but increasingly found this impossible to reconcile with his growing awareness of his homosexuality.[6]

In 1928 Pears went to Keble College, Oxford, to study music. He was not at this stage sure whether his musical future was as a singer or as player; during his brief time at the university, he was appointed temporary assistant organist at Hertford College, which was useful practical experience.[7] Headington comments that a musical conservatoire such as the Royal College of Music would have suited Pears better than the Oxford course, but at the time it was seen as a natural progression for an English public school boy to continue his education at Oxford or Cambridge. In the event Pears did not take to Oxford's academic regime, which required him to study a range of subjects before specialising in music. He failed the first-year examinations (Moderations) and though he was entitled to resit them he decided against doing so, and went down from Oxford.[7]

Teacher and singer

[edit]With no clear idea of his future, Pears took a teaching post at his old preparatory school in 1929.[8] Among his dearest friends were the twins Peter Burra and Nell Burra; Peter was a close friend from Lancing days, and Nell looked on Pears as almost another brother.[9] She urged him not to drift into a lifetime of schoolmastering, and he concluded that his future lay in singing. He later said that it was hearing the tenor Steuart Wilson (a distant cousin) singing the Evangelist in J S Bach's St Matthew Passion that "started me off".[10] He successfully applied for admission to the Royal College of Music in London, first as a part-time student and then, having been awarded a scholarship, studying full-time from 1934. He shared an apartment with Trevor Harvey and Basil Douglas.[11] He appeared in student productions of opera, finding himself wholly at home on the stage, and learning from the experience of singing Delius under Sir Thomas Beecham and roles in works by Mozart and Puccini.[12] But, as at Oxford, he failed to complete the course. He chafed at subsisting on a student's limited funds, and wanted a good, steady income. He auditioned for the BBC and was given a two-year contract as a member of the BBC Singers, a small vocal ensemble.[13]

In 1936 Pears made his first recording as a soloist, in Peter Warlock's "Corpus Christi Carol".[14] Headington comments on "a thoughtful word delivery and a sensitive moulding of quietly flowing phrases, but also a certain whiteness of tone ... a kind of English cathedral sound."[15] In the same year, after Peter Burra was given a long-term loan of a cottage on Bucklebury Common, Berkshire, Pears began to stay with him regularly, and it was through Burra that he got to be friendly with the rising young composer Benjamin Britten, who had become another good friend of Burra's. In 1937 Burra was killed in an air crash. Pears and Britten volunteered to clear his possessions from the cottage, and their daily contact during this period cemented their friendship.[16] Pears quickly became Britten's musical inspiration and close (though for the moment platonic) friend. Britten's first work for him was composed within weeks of their meeting, a setting of Emily Brontë's poem, "A thousand gleaming fires", for tenor and strings.[17]

Up to this point Pears had not pursued his career or his vocal training with any great determination. With the stimulus of Britten's music written for him he became much more focused. After their deaths John Amis wrote that Britten would have become a great composer without Pears, but that Pears would probably not have become a great singer without Britten.[18] Pears took vocal lessons from the eminent Lieder singer Elena Gerhardt, but they were of limited help to him, and it was some time before he found a wholly suitable voice coach.[19] In 1938 he had his first professional experience of opera, as an understudy and member of the chorus at Glyndebourne.[20]

America and wartime

[edit]

In April 1939, Pears accompanied Britten as he sailed to North America, going first to Canada and then to New York. Their relationship ceased to be platonic, and from then until Britten's death they were partners in both their professional and personal lives.[21] When the Second World War began, Britten and Pears turned for advice to the British embassy in Washington and were told that they should remain in the US as artistic ambassadors.[22] Pears was inclined to disregard the advice and go back to England; Britten also felt the urge to return, but accepted the embassy's counsel and persuaded Pears to do the same.[22]

In 1940 Britten composed Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, the first of many song cycles for Pears.[23] The composer and biographer David Matthews described the cycle as Britten's "declaration of love for Peter".[24] The partners made a private recording of the work in New York shortly after it was completed, but the public premiere was not for a further two years.[25] In 1941, spurred by a magazine article by E M Forster about the Suffolk poet George Crabbe, Pears bought Britten a copy of Crabbe's collection of narrative poems The Borough. He suggested to Britten that the section about the fisherman Peter Grimes would make a good subject for an opera. Britten agreed, and, a Suffolk man himself, was struck with a deep nostalgia by the poem. He later said, "I suddenly realised where I belonged and what I lacked". He and Pears began to plan their return to England.[26] They made the perilous Atlantic crossing in April 1942.[27]

Having arrived in England, Britten and Pears successfully applied for official recognition as conscientious objectors, Pears's application running much more smoothly than Britten's.[28] One of their early performances together after their return was the public premiere of the Michelangelo cycle at the Wigmore Hall in September 1942.[29] Their recording of the work for HMV was released in February 1943.[30] Britten was by now so obsessed with the sound of Pears's "heavenly voice" that he went out of his way to discourage sopranos from singing his earlier song cycle, Les Illuminations, though it had been specifically composed for the soprano voice.[31] For Pears, Britten composed one of his most popular works, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings (1943).[32]

In early 1943 Pears joined Sadler's Wells Opera Company. His roles included Tamino in The Magic Flute, Rodolfo in La bohème, the Duke in Rigoletto, Alfredo in La traviata, Almaviva in The Barber of Seville, Ferrando in Così fan tutte and Vašek in The Bartered Bride.[33] His growing operatic experience and expertise affected the composition of Britten's opera Peter Grimes. The composer had envisaged the central figure, based on Crabbe's brutal fisherman, as a villainous baritone, but he began to rethink the character as "neither a hero nor a villain" and not a baritone but a tenor, written to fit Pears's voice. In January 1944 Britten and Pears began a long association with the Decca Record Company, recording four of Britten's folk song arrangements.[14] In May of the same year, with Dennis Brain and the Boyd Neel Orchestra, they recorded the Serenade.[14]

Peter Grimes and English Opera Group

[edit]As the war was nearing its end, the artistic director of Sadler's Wells, the singer Joan Cross, announced her intention to re-open the company's home base in London with Britten's new opera Peter Grimes, casting herself and Pears in the leading roles.[n 1] There were complaints from company members about supposed favouritism and the "cacophony" of Britten's score, as well as some ill-suppressed homophobic remarks.[35] Peter Grimes opened in June 1945 and was hailed by public and critics.[36] Most of the extensive press coverage was to do with the work, but there was also high praise for the performances of Pears and Cross.[36] Dismayed by the in-fighting among the company, Cross, Britten and Pears severed their ties with Sadler's Wells in December 1945, going on to found what was to become the English Opera Group.[37]

Britten's next opera, The Rape of Lucretia, was presented at the first post-war Glyndebourne Festival, in 1946. It was a chamber piece for eight singers and an orchestra of twelve players. Pears and Cross were the Male and Female Chorus, with Kathleen Ferrier as Lucretia. After the festival, the work was taken on tour to provincial cities under the banner of the "Glyndebourne English Opera Company", an uneasy alliance of Britten and his associates with John Christie, the autocratic proprietor of Glyndebourne.[38] The tour lost money heavily, and Christie announced that he would underwrite no more tours.[39] Britten and his associates set up the English Opera Group; the librettist Eric Crozier and the designer John Piper joined Britten as artistic directors. The group's express purpose was to produce and commission new English operas and other works, presenting them throughout the country.[40] Britten wrote the comic opera Albert Herring for the group in 1947. Pears played the title role – one of his fairly rare excursions into comedy. Reviews of the opera were mixed, but Pears's performance as Albert, the mother's boy who kicks over the traces, received consistently good notices.[41]

Aldeburgh

[edit]While on tour as Albert, Pears came up with the idea of mounting a festival in the small Suffolk seaside town of Aldeburgh. Britten had bought a house there, and the town was his principal residence for the rest of his life.[42] The Aldeburgh Festival was launched in June 1948, with Britten, Pears and Crozier directing it.[43] For the inaugural festival, Albert Herring played at the Jubilee Hall, and Britten's new cantata Saint Nicolas, was presented in the parish church, with Pears as the tenor soloist.[44] The festival was an immediate success and became an annual event that has continued into the 21st century.[45]

New works by Britten featured in almost every festival until his death in 1976. They included operas in which leading roles were created by Pears, and written with his voice in mind. They ranged from the comic (Flute in A Midsummer Night's Dream, 1960) to the deeply serious (Aschenbach in Death in Venice, 1973).[46] His other creations at Aldeburgh included the Madwoman in Curlew River (1964), Nebuchadnezzar in The Burning Fiery Furnace (1966) and the Tempter in The Prodigal Son (1968).[47]

For the English Opera Group during the 1950s, Pears also sang Macheath in Britten's radically revised version of The Beggar's Opera, Satyavān in Holst's Sāvitri, and the title role in Mozart's Idomeneo.[47] At Covent Garden he created roles in operas by Britten and Walton: Vere in Billy Budd (1951), Essex in Gloriana (1953), and Pandarus in Troilus and Cressida (1954). Among his roles in older operas were Tamino, Vašek, and David in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.[47]

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s Pears continually expanded his recital and concert repertoire. He sang his first Gerontius in 1944, and the tenor part in Das Lied von der Erde in the same year. From the late 1940s he gained an international reputation as the Evangelist in the St Matthew Passion.[48] The music critic David Cairns wrote, "Pears's interpretation of the evangelist's part in the Bach Passions seemed complete as no other singer's: it encompassed every turn in the drama, the pity, the anger, the despair, the resignation."[49] In Lieder by Schubert, Schumann and others he was almost always accompanied by Britten, a partnership that Headington calls "as nearly an artistic unity as could be imagined";[50] Cairns calls their Lieder performances "never to be forgotten".[49] They made recordings for Decca of Die schöne Müllerin, Winterreise and Dichterliebe that have remained in print since their first issue in the 1960s.[14]

Later years

[edit]Among the highlights of Pears's career in the 1960s was the premiere of Britten's War Requiem in May 1962, marking the consecration of the new Coventry Cathedral. Britten composed it with the voices of Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Galina Vishnevskaya in mind. The Soviet authorities prevented Vishnevskaya from taking part (Heather Harper deputised) but in January 1963 all three intended soloists took part in a Decca recording conducted by Britten, which unexpectedly became a bestseller.[51] As well as his performing partnership with Britten, Pears established another with Julian Bream, who, as a lutenist, accompanied him in many works, most notably those of English composers of the Tudor period.[3]

Pears and Britten maintained an arduous international touring schedule, and made many broadcasts and gramophone recordings. In the 1970s Pears created roles in Britten's last two operas, playing General Wingrave in Owen Wingrave recorded at Aldeburgh for its premiere, which was on BBC television, and Aschenbach in Death in Venice (1973).[47] It was in the latter role that Pears made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, at the age of 64.[49]

Following Britten's death in 1976, Pears had the good fortune to find another accompanist with whom he could collaborate fruitfully. With Murray Perahia, Pears gave performances of such works as Britten's Michelangelo Sonnets and Schumann's Liederkreis to critical acclaim.[49] He continued to perform until a stroke ended his singing career in 1980 shortly after the celebrations marking his seventieth birthday. After that he remained an active director of the Aldeburgh Festival, and taught at the Britten-Pears School which he and his partner had set up in 1972.[3]

Pears died in Aldeburgh on 3 April 1986 at the age of 75. He was buried beside Britten in the churchyard of the parish church of St Peter and St Paul, Aldeburgh.[3]

Voice

[edit]Pears's voice was both unmistakable and controversial. Some music-lovers found his characteristic timbre uncongenial.[3] The critic Alan Blyth described it thus:

Clear, reedy and almost instrumental in quality, it was capable of great expressive variety and flexibility, if no wide range of colour. Its inward, reflective timbre, tinged with poetry, was artfully exploited by Britten, from the role of Peter Grimes to that of Aschenbach, but the voice could also be commanding, almost heroic, as was shown in the more vehement sections of Captain Vere's role or in the part of the Madwoman in Curlew River.[47]

David Cairns broadly concurred, writing:

His voice … was not beautiful in itself; its reedy timbre was so idiosyncratic that for some people it came between them and the music. Even his countless admirers might have agreed that, objectively considered, it lacked warmth and variety of colour. But so great was his skill and so subtle and imaginative his musical sensitivity and mastery of inflection that it conveyed, together with his air of patrician authority, an extraordinary richness of atmosphere and feeling.[49]

Honours and awards

[edit]Pears was awarded honorary degrees or fellowships by three music academies and nine universities in the UK and US.[52] He was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1957, and knighted in 1978.[52] Other awards included the Queen's Jubilee Medal, 1977, Musician of the Year, Incorporated Society of Musicians, 1978, and the Royal Opera House's Long Service Medal, 1979.[52]

Recordings

[edit]For Decca, Pears recorded almost all the music written for him by Britten. The major exception is the role of the Earl of Essex in Gloriana, which was not recorded until after Britten and Pears were dead.[14] Pears's other Decca recordings range from early music by Dowland, Schütz and their contemporaries to Walton's Façade, and include such varied repertory as the Emperor in Puccini's Turandot, the title role in Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, and the tenor part in Berlioz's L'enfance du Christ.[14] His recordings for other companies include the role of the Evangelist in Bach's St Matthew Passion (Otto Klemperer's 1961 EMI version), the tenor part in the same composer's Mass in B minor and Fauré's La bonne chanson.[53]

Notes and references

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Sadler's Wells Theatre in Islington, London, was requisitioned by the government in 1942 as a refuge for people made homeless by air-raids; the Sadler's Wells opera company toured the British provinces, returning to its home base in June 1945.[34]

- References

- ^ Sir Bernard Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Landed Gentry, 14th ed. (London 1925), pp. 1135−1137.

- ^ Headington, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f Mitchell, Donald. "Pears, Sir Peter Neville Luard (1910–1986)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, October 2006, accessed 15 October 2013 (subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Headington, pp. 22–23

- ^ Headington, p. 26

- ^ Headington, p. 15

- ^ a b Headington, pp. 27–29

- ^ "Obituary: Sir Peter Pears", The Times, 4 April 1986, p. 14

- ^ Headington, p. 18

- ^ Pears, p. 225

- ^ Pears, Peter (1999). The Travel Diaries of Peter Pears, 1936–1978. Boydell & Brewer. p. 12. ISBN 9780851157412. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ Headington, pp. 40–41

- ^ Headington, p. 42

- ^ a b c d e f Stuart, Philip. Decca Classical 1929–2009, accessed 14 October 2013.

- ^ Headington, pp. 53–54

- ^ Powell, p. 130

- ^ Carpenter, p. 112

- ^ Amis, John. "His maestro's silver voice and love", The Times, 13 June 1992, p. 43

- ^ Headington, p. 75

- ^ Headington, p. 82

- ^ Headington, pp. 87–88

- ^ a b Powell, p. 197

- ^ Headington, pp. 98–99

- ^ Matthews, p. 56

- ^ Headington, p. 99

- ^ Headington, pp. 110–111

- ^ Powell, p. 210

- ^ Matthews, p. 66

- ^ Headington, p. 120

- ^ "The Gramophone Company Limited", The Times, 12 February 1943, p. 3

- ^ Headington, pp. 122–123

- ^ Powell, p. 229

- ^ Headington, p. 124

- ^ Gilbert pp. 78, 83 and 98

- ^ Gilbert, p. 98

- ^ a b See, for example, "Sadler's Wells Opera – 'Peter Grimes'", The Times, 8 June 1945, p. 6, and Glock, William. "Music", The Observer, 10 June 1945, p. 2

- ^ Gilbert, p. 107

- ^ Hope-Wallace, Philip. "Opera at Glyndebourne", The Manchester Guardian, 15 July 1946, p. 3; and Carpenter, pp. 242–243

- ^ Carpenter, p. 243

- ^ Wood, Anne. "English Opera Group", The Times, 12 July 1947, p. 5

- ^ "Albert Herring", The Times, 21 June 1947, p. 6; "Maupassant Reversed", The Observer, 22 June 1947, p. 2; "A New Britten Opera", The Manchester Guardian, 23 June 1947, p. 3; and "At Covent Garden", The Observer, 12 October 1947, p. 2

- ^ Headington (1993), pp. 149–150; and Matthews, p. 89

- ^ White, p. 60

- ^ Matthews, pp. 92–93

- ^ Hall, George. "Festival Overtures: Britten in Bloom", Opera, Volume 64.4, April 2013, pp. 436–438

- ^ Mason, Colin. "Benjamin Britten's 'Dream'", The Guardian, 11 June 1960, p. 5; and Greenfield, Edward. "Britten's Death in Venice", The Guardian, 18 June 1973, p. 8

- ^ a b c d e Blyth, Alan (25 May 2016). "Pears, Sir Peter (Neville Luard)". Grove Music Online. revised by Heather Wiebe (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.21147. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. (subscription, Wikilibrary access, or UK public library membership required) (subscription required)

- ^ Headington, p. 149

- ^ a b c d e Cairns, David. "A tenor of rare intelligence – Obituary of Sir Peter Pears", The Sunday Times, 6 April 1986

- ^ Headington, p. 147

- ^ Culshaw, p. 339

- ^ a b c "Pears, Sir Peter", Who Was Who, A & C Black, online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2012, accessed 15 October 2013 (subscription required)

- ^ York, Steve. "Sir Peter Pears: An annotated bibliography". Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. 63. ProQuest 1110684.

Sources

[edit]- Carpenter, Humphrey (1992). Benjamin Britten: A Biography. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571143245.

- Culshaw, John (1981). Putting the Record Straight. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0436118025.

- Gilbert, Susie (2009). Opera for Everybody. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0571224937.

- Headington, Christopher (1992). Peter Pears: A Biography. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571170722.

- Matthews, David (2013). Britten. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1908323385.

- Pears, Peter (1995). Reed, Philip (ed.). Travel Diaries 1936–1978. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 085115364X.

- Powell, Neil (2013). Britten: A Life for Music. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0091931230.

- White, Eric Walker (1970) [1954]. Benjamin Britten: His Life and Operas. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520016798.

External links

[edit] Media related to Peter Pears at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Peter Pears at Wikimedia Commons- "Peter Pears (Tenor)". Bach Cantatas.

Peter Pears

View on GrokipediaSir Peter Pears (22 June 1910 – 3 April 1986) was an English tenor whose vocal career was defined by his close collaboration with composer Benjamin Britten, creating the principal tenor roles in nearly all of Britten's operas and serving as the muse for much of his vocal output.[1][2] Born in Farnham, Surrey, Pears studied at the Royal College of Music and met Britten in 1937, forming a partnership that lasted until Britten's death in 1976 and encompassed both artistic endeavors and personal companionship.[3][4] Pears premiered roles such as the title character in Peter Grimes (1945), Captain Vere in Billy Budd (1951), and Aschenbach in Death in Venice (1973), works composed expressly to suit his light, lyrical tenor voice and precise diction.[5] Beyond Britten's repertoire, he excelled in interpretations of Bach's Evangelist in the St. Matthew Passion and Elizabethan lute songs, often partnering with guitarist Julian Bream.[6] Knighted in 1978 for his contributions to music, Pears co-founded the Aldeburgh Festival in 1948 with Britten, where he performed annually until health issues curtailed his stage appearances in later years.[2][3]