Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thomas Beecham

View on Wikipedia

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, CH (29 April 1879 – 8 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with the Liverpool Philharmonic and Hallé orchestras. From the early 20th century until his death, Beecham was a major influence on the musical life of Britain and, according to the BBC, was Britain's first international conductor.

Born to a rich industrial family, Beecham began his career as a conductor in 1899. He used his access to the family fortune to finance opera from the 1910s until the start of the Second World War, staging seasons at Covent Garden, Drury Lane and His Majesty's Theatre with international stars, his own orchestra and a wide repertoire. Among the works he introduced to England were Richard Strauss's Elektra, Salome and Der Rosenkavalier and three operas by Frederick Delius.

Together with his younger colleague Malcolm Sargent, Beecham founded the London Philharmonic, and he conducted its first performance at the Queen's Hall in 1932. In the 1940s he worked for three years in the United States, where he was music director of the Seattle Symphony and conducted at the Metropolitan Opera. After his return to Britain, he founded the Royal Philharmonic in 1946 and conducted it until his death in 1961.

Beecham's repertoire was eclectic, sometimes favouring lesser-known composers over famous ones. His specialities included composers whose works were neglected in Britain before he became their advocate, such as Delius and Berlioz. Other composers with whose music he was frequently associated were Haydn, Schubert, Sibelius and the composer he revered above all others, Mozart.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]

Beecham was born in St Helens, Lancashire (now Merseyside), in a house adjoining the Beecham's Pills laxative factory founded by his grandfather, Thomas Beecham.[1] His parents were Joseph Beecham, the elder son of Thomas, and Josephine, née Burnett.[1] In 1885, with the family firm flourishing financially, Joseph Beecham moved his family to a large house in Ewanville, Huyton, near Liverpool. Their former home was demolished to make room for an extension to the pill factory.[2]

Beecham was educated at Rossall School between 1892 and 1897, after which he hoped to attend a music conservatoire in Germany, but his father forbade it, and instead Beecham went to Wadham College, Oxford to read Classics.[3] He did not find university life to his taste and successfully sought his father's permission to leave Oxford in 1898.[4] He studied as a pianist but, despite his excellent natural talent and fine technique, he had difficulty because of his small hands, and any career as a soloist was ruled out by a wrist injury in 1904.[5][6] He studied composition with Frederic Austin in Liverpool, Charles Wood in London, and Moritz Moszkowski in Paris.[n 1] As a conductor, he was self-taught.[9]

First orchestras

[edit]Beecham first conducted in public in St. Helens in October 1899, with an ad hoc ensemble comprising local musicians and players from the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and the Hallé in Manchester.[4] A month later, he stood in at short notice for the celebrated conductor Hans Richter at a concert by the Hallé to mark Joseph Beecham's inauguration as mayor of St Helens.[4] Soon afterwards, Joseph Beecham secretly committed his wife to a mental hospital.[n 2] Thomas and his elder sister Emily helped to secure their mother's release and to force their father to pay annual alimony of £4,500.[11] For this, Joseph disinherited them. Beecham was estranged from his father for ten years.[12]

Beecham's professional début as a conductor was in 1902 at the Shakespeare Theatre, Clapham, with Balfe's The Bohemian Girl, for the Imperial Grand Opera Company.[13] He was engaged as assistant conductor for a tour and was allotted four other operas, including Carmen and Pagliacci.[13] A Beecham biographer calls the company "grandly named but decidedly ramshackle",[13] though Beecham's Carmen was Zélie de Lussan, a leading exponent of the title role.[14] Beecham was also composing music in these early years, but he was not satisfied with his own efforts and instead concentrated on conducting.[15][n 3]

In 1906 Beecham was invited to conduct the New Symphony Orchestra, a recently formed ensemble of 46 players, in a series of concerts at the Bechstein Hall in London.[17] Throughout his career, Beecham frequently chose to programme works to suit his own tastes rather than those of the paying public. In his early discussions with his new orchestra, he proposed works by a long list of barely known composers such as Étienne Méhul, Nicolas Dalayrac and Ferdinando Paer.[18] During this period, Beecham first encountered the music of Frederick Delius, which he at once loved deeply and with which he became closely associated for the rest of his life.[19]

Beecham quickly concluded that to compete with the two existing London orchestras, the Queen's Hall Orchestra and the recently founded London Symphony Orchestra (LSO), his forces must be expanded to full symphonic strength and play in larger halls.[20] For two years starting in October 1907, Beecham and the enlarged New Symphony Orchestra gave concerts at the Queen's Hall. He paid little attention to the box office: his programmes were described by a biographer as "even more certain to deter the public then than it would be in our own day".[21] The principal pieces of his first concert with the orchestra were d'Indy's symphonic ballad La forêt enchantée, Smetana's symphonic poem Šárka, and Lalo's little-known Symphony in G minor.[22] Beecham retained an affection for the last work: it was among the works he conducted at his final recording sessions more than fifty years later.[23]

In 1908 Beecham and the New Symphony Orchestra parted company, disagreeing about artistic control and, in particular, the deputy system. Under this system, orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement elsewhere, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert.[24] The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away."[25][n 4] Henry Wood had already banned the deputy system in the Queen's Hall Orchestra (provoking rebel players to found the London Symphony Orchestra), and Beecham followed suit.[26] The New Symphony Orchestra survived without him and subsequently became the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra.[26]

In 1909, Beecham founded the Beecham Symphony Orchestra.[27] He did not poach from established symphony orchestras, but instead he recruited from theatre bandrooms, local symphony societies, the palm courts of hotels, and music colleges.[28] The result was a youthful team – the average age of his players was 25. They included names that would become celebrated in their fields, such as Albert Sammons, Lionel Tertis, Eric Coates and Eugene Cruft.[27]

Because he persistently programmed works that did not attract the public, Beecham's musical activities at this time consistently lost money. As a result of his estrangement from his father between 1899 and 1909, his access to the Beecham family fortune was strictly limited. From 1907 he had an annuity of £700 left to him in his grandfather's will, and his mother subsidised some of his loss-making concerts,[12] but it was not until father and son were reconciled in 1909 that Beecham was able to draw on the family fortune to promote opera.[29]

1910–1920

[edit]From 1910, subsidised by his father, Beecham realised his ambition to mount opera seasons at Covent Garden and other houses. In the Edwardian opera house, the star singers were regarded as all-important, and conductors were seen as ancillary.[30] Between 1910 and 1939 Beecham did much to change the balance of power.[30]

In 1910, Beecham either conducted or was responsible as impresario for 190 performances at Covent Garden and His Majesty's Theatre. His assistant conductors were Bruno Walter and Percy Pitt.[31] During the year, he mounted 34 different operas, most of them either new to London or almost unknown there.[32] Beecham later acknowledged that in his early years the operas he chose to present were too obscure to attract the public.[33] During his 1910 season at His Majesty's, the rival Grand Opera Syndicate put on a concurrent season of its own at Covent Garden; London's total opera performances for the year amounted to 273 performances, far more than the box-office demand could support.[34] Of the 34 operas that Beecham staged in 1910, only four made money: Richard Strauss's new operas Elektra and Salome, receiving their first, and highly publicised, performances in Britain, and The Tales of Hoffmann and Die Fledermaus.[35][n 5]

In 1911 and 1912, the Beecham Symphony Orchestra played for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, both at Covent Garden and at the Krolloper in Berlin, under the batons of Beecham and Pierre Monteux, Diaghilev's chief conductor. Beecham was much admired for conducting the complicated new score of Stravinsky's Petrushka, at two days' notice and without rehearsal, when Monteux became unavailable.[37] While in Berlin, Beecham and his orchestra, in Beecham's words, caused a "mild stir", scoring a triumph: the orchestra was agreed by the Berlin press to be an elite body, one of the best in the world.[38] The principal Berlin musical weekly, Die Signale, asked, "Where does London find such magnificent young instrumentalists?" The violins were credited with rich, noble tone, the woodwinds with lustre, the brass, "which has not quite the dignity and amplitude of our best German brass", with uncommon delicacy of execution.[38]

Beecham's 1913 seasons included the British premiere of Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier at Covent Garden, and a "Grand Season of Russian Opera and Ballet" at Drury Lane.[39] At the latter there were three operas, all starring Feodor Chaliapin, and all new to Britain: Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina, and Rimsky-Korsakov's Ivan the Terrible. There were also 15 ballets, with leading dancers including Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina.[40] The ballets included Debussy's Jeux and his controversially erotic L'après-midi d'un faune, and the British premiere of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring, six weeks after its first performance in Paris.[40] Beecham shared Monteux's private dislike of the piece, much preferring Petrushka.[41] Beecham did not conduct during this season; Monteux and others conducted the Beecham Symphony Orchestra. The following year, Beecham and his father presented Rimsky-Korsakov's The Maid of Pskov and Borodin's Prince Igor, with Chaliapin, and Stravinsky's The Nightingale.[9]

During the First World War, Beecham strove, often without a fee, to keep music alive in London, Liverpool, Manchester and other British cities.[42] He conducted for, and gave financial support to, three institutions with which he was connected at various times: the Hallé Orchestra, the LSO and the Royal Philharmonic Society. In 1915 he formed the Beecham Opera Company, with mainly British singers, performing in London and throughout the country. In 1916, he received a knighthood in the New Year Honours[43] and succeeded to the baronetcy on his father's death later that year.[44]

After the war, there were joint Covent Garden seasons with the Grand Opera Syndicate in 1919 and 1920, but these were, according to a biographer, pale confused echoes of the years before 1914.[45] These seasons included forty productions, of which Beecham conducted only nine.[45] After the 1920 season, Beecham temporarily withdrew from conducting to deal with a financial problem that he described as "the most trying and unpleasant experience of my life".[46]

Covent Garden estate

[edit]

Influenced by an ambitious financier, James White, Sir Joseph Beecham had agreed, in July 1914, to buy the Covent Garden estate from the Duke of Bedford and float a limited company to manage the estate commercially.[47] The deal was described by The Times as "one of the largest ever carried out in real estate in London".[48] Sir Joseph paid an initial deposit of £200,000 and covenanted to pay the balance of the £2 million purchase price on 11 November. Within a month, however, the First World War broke out, and new official restrictions on the use of capital prevented the completion of the contract.[47] The estate and market continued to be managed by the Duke's staff, and in October 1916, Joseph Beecham died suddenly, with the transaction still uncompleted.[49] The matter was brought before the civil courts with the aim of disentangling Sir Joseph's affairs; the court and all parties agreed that a private company should be formed, with his two sons as directors, to complete the Covent Garden contract. In July 1918, the Duke and his trustees conveyed the estate to the new company, subject to a mortgage of the balance of the purchase price still outstanding: £1.25 million.[49]

Beecham and his brother Henry had to sell enough of their father's estate to discharge this mortgage. For more than three years, Beecham was absent from the musical scene, working to sell property worth over £1 million.[49] By 1923 enough money had been raised. The mortgage was discharged, and Beecham's personal liabilities, amounting to £41,558, were paid in full.[50] In 1924 the Covent Garden property and the pill-making business at St Helens were united in one company, Beecham Estates and Pills. The nominal capital was £1,850,000, of which Beecham had a substantial share.[49]

London Philharmonic

[edit]After his absence, Beecham first reappeared on the rostrum conducting the Hallé in Manchester in March 1923, in a programme including works by Berlioz, Bizet, Delius and Mozart.[51] He returned to London the following month, conducting the combined Royal Albert Hall Orchestra (the renamed New Symphony Orchestra) and London Symphony Orchestra in April 1923. The main work on the programme was Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben.[52] No longer with an orchestra of his own, Beecham established a relationship with the London Symphony Orchestra that lasted for the rest of the 1920s. Towards the end of the decade, he negotiated inconclusively with the BBC over the possibility of establishing a permanent radio orchestra.[53]

In 1931, Beecham was approached by the rising young conductor Malcolm Sargent with a proposal to set up a permanent, salaried orchestra with a subsidy guaranteed by Sargent's patrons, the Courtauld family.[54] Originally Sargent and Beecham envisaged a reshuffled version of the London Symphony Orchestra, but the LSO, a self-governing co-operative, balked at weeding out and replacing underperforming players. In 1932 Beecham lost patience and agreed with Sargent to set up a new orchestra from scratch.[55] The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), as it was named, consisted of 106 players including a few young musicians straight from music college, many established players from provincial orchestras, and 17 of the LSO's leading members.[56] The principals included Paul Beard, George Stratton, Anthony Pini, Gerald Jackson, Léon Goossens, Reginald Kell, James Bradshaw and Marie Goossens.[57]

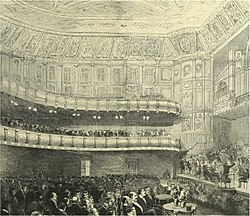

The orchestra made its debut at the Queen's Hall on 7 October 1932, conducted by Beecham. After the first item, Berlioz's Roman Carnival Overture, the audience went wild, some of them standing on their seats to clap and shout.[58] During the next eight years, the LPO appeared nearly a hundred times at the Queen's Hall for the Royal Philharmonic Society alone, played for Beecham's opera seasons at Covent Garden, and made more than 300 gramophone records.[59] Berta Geissmar, his secretary from 1936, wrote, "The relations between the Orchestra and Sir Thomas were always easy and cordial. He always treated a rehearsal as a joint undertaking with the Orchestra. … The musicians were entirely unselfconscious with him. Instinctively they accorded him the artistic authority which he did not expressly claim. Thus he obtained the best from them and they gave it without reserve."[60]

By the early 1930s, Beecham had secured substantial control of the Covent Garden opera seasons.[61] Wishing to concentrate on music-making rather than management, he assumed the role of artistic director, and Geoffrey Toye was recruited as managing director. In 1933, Tristan und Isolde with Frida Leider and Lauritz Melchior was a success, and the season continued with the Ring cycle and nine other operas.[62] The 1934 season featured Conchita Supervía in La Cenerentola, and Lotte Lehmann and Alexander Kipnis in the Ring.[63] Clemens Krauss conducted the British première of Strauss's Arabella. During 1933 and 1934, Beecham repelled attempts by John Christie to form a link between Christie's new Glyndebourne Festival and the Royal Opera House.[64] Beecham and Toye fell out over the latter's insistence on bringing in a popular film star, Grace Moore, to sing Mimi in La bohème. The production was a box-office success, but an artistic failure.[65] Beecham manoeuvred Toye out of the managing directorship in what their fellow conductor Sir Adrian Boult described as an "absolutely beastly" manner.[66]

From 1935 to 1939, Beecham, now in sole control, presented international seasons with eminent guest singers and conductors.[67] Beecham conducted between a third and half of the performances each season. He intended the 1940 season to include the first complete performances of Berlioz's Les Troyens, but the outbreak of the Second World War caused the season to be abandoned. Beecham did not conduct again at Covent Garden until 1951, and by then it was no longer under his control.[68]

Beecham took the London Philharmonic on a controversial tour of Germany in 1936.[70] There were complaints that he was being used by Nazi propagandists, and Beecham complied with a Nazi request not to play the Scottish Symphony of Mendelssohn, who was a Christian by faith but a Jew by birth.[n 6] In Berlin, Beecham's concert was attended by Adolf Hitler, whose lack of punctuality caused Beecham to remark very audibly, "The old bugger's late."[74] After this tour, Beecham refused renewed invitations to give concerts in Germany,[75] although he honoured contractual commitments to conduct at the Berlin State Opera, in 1937 and 1938, and recorded The Magic Flute for EMI in the Beethovensaal in Berlin in the same years.[76]

As his sixtieth birthday approached, Beecham was advised by his doctors to take a year's complete break from music, and he planned to go abroad to rest in a warm climate.[77] The Australian Broadcasting Commission had been seeking for several years to get him to conduct in Australia.[77] The outbreak of war on 3 September 1939 obliged him to postpone his plans for several months, striving instead to secure the future of the London Philharmonic, whose financial guarantees had been withdrawn by its backers when war was declared.[78] Before leaving, Beecham raised large sums of money for the orchestra and helped its members to form themselves into a self-governing company.[79]

1940s

[edit]Beecham left Britain in the spring of 1940, going first to Australia and then to North America. He became music director of the Seattle Symphony in 1941.[80] In 1942 he joined the Metropolitan Opera as joint senior conductor with his former assistant Bruno Walter. He began with his own adaptation of Bach's comic cantata, Phoebus and Pan, followed by Le Coq d'Or. His main repertoire was French: Carmen, Louise (with Grace Moore), Manon, Faust, Mignon and The Tales of Hoffmann. In addition to his Seattle and New York posts, Beecham was guest conductor with 18 American orchestras.[81]

In 1944, Beecham returned to Britain. Musically his reunion with the London Philharmonic was triumphant, but the orchestra, now, after his help in 1939, a self-governing co-operative, attempted to hire him on its own terms as its salaried artistic director.[82] "I emphatically refuse", concluded Beecham, "to be wagged by any orchestra ... I am going to found one more great orchestra to round off my career."[83] When Walter Legge founded the Philharmonia Orchestra in 1945, Beecham conducted its first concert. But he was not disposed to accept a salaried position from Legge, his former assistant, any more than from his former players in the LPO.[83]

In 1946, Beecham founded the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO), securing an agreement with the Royal Philharmonic Society that the new orchestra should replace the LPO at all the Society's concerts.[83] Beecham later agreed with the Glyndebourne Festival that the RPO should be the resident orchestra at Glyndebourne each summer. He secured backing, including that of record companies in the US as well as Britain, with whom lucrative recording contracts were negotiated.[83] As in 1909 and in 1932, Beecham's assistants recruited in the freelance pool and elsewhere. Original members of the RPO included James Bradshaw, Dennis Brain, Leonard Brain, Archie Camden, Gerald Jackson and Reginald Kell.[84] The orchestra later became celebrated for its regular team of woodwind principals, often referred to as "The Royal Family", consisting of Jack Brymer (clarinet), Gwydion Brooke (bassoon), Terence MacDonagh (oboe) and Gerald Jackson (flute).[85]

Beecham's long association with the Hallé Orchestra as a guest conductor ceased after John Barbirolli became the orchestra's chief conductor in 1944. Beecham was, to his great indignation, ousted from the honorary presidency of the Hallé Concerts Society,[86] and Barbirolli refused to "let that man near my orchestra".[87] Beecham's relationship with the Liverpool Philharmonic, which he had first conducted in 1911, was resumed harmoniously after the war. A manager of the orchestra recalled, "It was an unwritten law in Liverpool that first choice of dates offered to guest conductors was given to Beecham. ... In Liverpool there was one over-riding factor – he was adored."[88]

1950s and later years

[edit]Beecham, whom the BBC called "Britain's first international conductor",[89] took the RPO on a strenuous tour through the United States, Canada and South Africa in 1950.[9][5] During the North American tour, Beecham conducted 49 concerts in almost daily succession.[90] In 1951, he was invited to conduct at Covent Garden after a 12-year absence.[91] State-funded for the first time, the opera company operated quite differently from his pre-war regime. Instead of short, star-studded seasons, with a major symphony orchestra, the new director David Webster was attempting to build up a permanent ensemble of home-grown talent performing all the year round, in English translations. Extreme economy in productions and great attention to the box-office were essential, and Beecham, though he had been hurt and furious at his exclusion, was not suited to participate in such an undertaking.[92] When offered a chorus of eighty singers for his return, conducting Die Meistersinger, he insisted on augmenting their number to 200. He also, contrary to Webster's policy, insisted on performing the piece in German.[91] In 1953 at Oxford, Beecham presented the world premiere of Delius's first opera, Irmelin, and his last operatic performances in Britain were in 1955 at Bath, with Grétry's Zémire et Azor.[5]

Between 1951 and 1960, Beecham conducted 92 concerts at the Royal Festival Hall.[93] Characteristic Beecham programmes of the RPO years included symphonies by Bizet, Franck, Haydn, Schubert and Tchaikovsky; Richard Strauss's Ein Heldenleben; concertos by Mozart and Saint-Saëns; a Delius and Sibelius programme; and many of his favoured shorter pieces.[94] He did not stick uncompromisingly to his familiar repertoire. After the sudden death of the German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1954, Beecham in tribute conducted the two programmes his colleague had been due to present at the Festival Hall; these included Bach's Third Brandenburg Concerto, Ravel's Rapsodie espagnole, Brahms's Symphony No. 1, and Barber's Second Essay for Orchestra.[95]

In the summer of 1958, Beecham conducted a season at the Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, Argentina, consisting of Verdi's Otello, Bizet's Carmen, Beethoven's Fidelio, Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah and Mozart's The Magic Flute. These were his last operatic performances.[96] It was during this season that Betty Humby died suddenly. She was cremated in Buenos Aires and her ashes returned to England. Beecham's own last illness prevented his operatic debut at Glyndebourne in a planned Magic Flute and a final appearance at Covent Garden conducting Berlioz's The Trojans.[n 7]

Sixty-six years after his first visit to America, Beecham made his last, beginning in late 1959, conducting in Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago and Washington. During this tour, he also conducted in Canada. He flew back to London on 12 April 1960 and did not leave England again.[98] His final concert was at Portsmouth Guildhall on 7 May 1960. The programme, all characteristic choices, comprised the Magic Flute Overture, Haydn's Symphony No. 100 (the Military), Beecham's own Handel arrangement, Love in Bath, Schubert's Symphony No. 5, On the River by Delius, and the Bacchanale from Samson and Delilah.[99]

Beecham died of a coronary thrombosis at his London residence, aged 81, on 8 March 1961.[100] He was buried two days later in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey. Owing to changes at Brookwood, his remains were exhumed in 1991 and reburied in St Peter's Churchyard at Limpsfield, Surrey, close to the joint grave of Delius and his wife Jelka Rosen.[101]

Personal life

[edit]

Beecham was married three times. In 1903 he married Utica Celestina Welles, daughter of Dr Charles S. Welles, of New York, and his wife Ella Celeste, née Miles.[102] Beecham and his wife had two sons: Adrian, born in 1904, who became a composer and achieved some celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s,[103] and Thomas, born in 1909.[12] After the birth of his second child, Beecham began to drift away from the marriage. By 1911, no longer living with his wife and family, he was involved as co-respondent in a much-publicised divorce case.[104] Utica ignored advice that she should divorce him and secure substantial alimony; she did not believe in divorce.[105] She never remarried after Beecham divorced her (in 1943), and she outlived her former husband by sixteen years, dying in 1977.[106]

In 1909 or early 1910, Beecham began an affair with Maud Alice (known as Emerald), Lady Cunard. Although they never lived together, it continued, despite other relationships on his part, until his remarriage in 1943.[5] She was a tireless fund-raiser for his musical enterprises.[107] Beecham's biographers are agreed that she was in love with him, but that his feelings for her were less strong.[105][108] During the 1920s and 1930s, Beecham also had an affair with Dora Labbette, a soprano sometimes known as Lisa Perli, with whom he had a son, Paul Strang, born in March 1933.[109] Strang, a lawyer who served on the boards of several musical institutions, died in April 2024.[110]

In 1943 Lady Cunard was devastated to learn (not from Beecham) that he intended to divorce Utica to marry Betty Humby, a concert pianist 29 years his junior.[111] Beecham married Betty in 1943, and they were a devoted couple until her death in 1958.[96] On 10 August 1959, two years before his death, he married in Zurich his former secretary, Shirley Hudson, who had worked for the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra's administration since 1950. She was 27, he 80.[112]

Repertoire

[edit]Handel, Haydn, and Mozart

[edit]

The earliest composer whose music Beecham regularly performed was Handel, whom he called, "the great international master of all time. ... He wrote Italian music better than any Italian; French music better than any Frenchman; English music better than any Englishman; and, with the exception of Bach, outrivalled all other Germans."[113] In his performances of Handel, Beecham ignored what he called the "professors, pedants, pedagogues".[114] He followed Mendelssohn and Mozart in editing and reorchestrating Handel's scores to suit contemporary tastes.[114] At a time when Handel's operas were scarcely known, Beecham knew them so well that he was able to arrange three ballets, two other suites and a piano concerto from them.[n 8] He gave Handel's oratorio Solomon its first performance since the 18th century, with a text edited by the conductor.[116]

With Haydn, too, Beecham was far from an authenticist, using unscholarly 19th-century versions of the scores, avoiding the use of the harpsichord, and phrasing the music romantically.[117] He recorded the twelve "London" symphonies, and regularly programmed some of them in his concerts.[118] Earlier Haydn works were unfamiliar in the first half of the 20th century, but Beecham conducted several of them, including the Symphony No. 40 and an early piano concerto.[119] He programmed The Seasons regularly throughout his career, recording it for EMI in 1956, and in 1944 added The Creation to his repertoire.[114]

For Beecham, Mozart was "the central point of European music,"[120] and he treated the composer's scores with more deference than he gave most others. He edited the incomplete Requiem, made English translations of at least two of the great operas, and introduced Covent Garden audiences who had rarely if ever heard them to Così fan tutte, Der Schauspieldirektor and Die Entführung aus dem Serail; he also regularly programmed The Magic Flute, Don Giovanni and The Marriage of Figaro.[121][n 9] He considered the best of Mozart's piano concertos to be "the most beautiful compositions of their kind in the world", and he played them many times with Betty Humby-Beecham and others.[127]

German music

[edit]

Beecham's attitude towards 19th-century German repertoire was equivocal. He frequently disparaged Beethoven, Wagner and others, but regularly conducted their works, often with great success.[128] He observed, "Wagner, though a tremendous genius, gorged music like a German who overeats. And Bruckner was a hobbledehoy who had no style at all ... Even Beethoven thumped the tub; the Ninth symphony was composed by a kind of Mr. Gladstone of music."[128] Despite his criticisms, Beecham conducted all the Beethoven symphonies during his career, and he made studio recordings of Nos. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 8, and live recordings of No. 9 and Missa Solemnis.[129] He conducted the Fourth Piano Concerto with pleasure (recording it with Arthur Rubinstein and the LPO) but avoided the Emperor Concerto when possible.[130]

Beecham was not known for his Bach[131] but nonetheless chose Bach (arranged by Beecham) for his debut at the Metropolitan Opera. He later gave the Third Brandenburg Concerto in one of his memorial concerts for Wilhelm Furtwängler (a performance described by The Times as "a travesty, albeit an invigorating one").[132] In Brahms's music, Beecham was selective. He made a speciality of the Second Symphony[130] but conducted the Third only occasionally,[n 10] the First rarely, and the Fourth never. In his memoirs he made no mention of any Brahms performance after the year 1909.[134]

Beecham was a great Wagnerian,[135] despite his frequent expostulation about the composer's length and repetitiousness: "We've been rehearsing for two hours – and we're still playing the same bloody tune!"[136] Beecham conducted all the works in the regular Wagner canon with the exception of Parsifal, which he presented at Covent Garden but never with himself in the pit.[137][138] The chief music critic of The Times observed: "Beecham's Lohengrin was almost Italian in its lyricism; his Ring was less heroic than Bruno Walter's or Furtwängler's, but it sang from beginning to end".[139]

Richard Strauss had a lifelong champion in Beecham, who introduced Elektra, Salome, Der Rosenkavalier and other operas to England. Beecham programmed Ein Heldenleben from 1910 until his last year; his final recording of it was released shortly after his death.[130][140] Don Quixote, Till Eulenspiegel, the Bourgeois Gentilhomme music and Don Juan also featured in his repertory, but not Also Sprach Zarathustra or Tod und Verklärung.[141] Strauss had the first and last pages of the manuscript of Elektra framed and presented them to "my highly honoured friend ... and distinguished conductor of my work."[142]

French and Italian music

[edit]In the opinion of the jury of the Académie du Disque Français, "Sir Thomas Beecham has done more for French music abroad than any French conductor".[143] Berlioz featured prominently in Beecham's repertoire throughout his career, and in an age when the composer's works received little exposure, Beecham presented most of them and recorded many. Along with Sir Colin Davis, Beecham has been described as one of the two "foremost modern interpreters" of Berlioz's music.[144] Both in concert and the recording studio, Beecham's choices of French music were characteristically eclectic.[145] He avoided Ravel but regularly programmed Debussy. Fauré did not feature often, although his orchestral Pavane was an exception; Beecham's final recording sessions in 1959 included the Pavane and the Dolly Suite.[146] Bizet was among Beecham's favourites, and other French composers favoured by him included Gustave Charpentier, Delibes, Duparc, Grétry, Lalo, Lully, Offenbach, Saint-Saëns and Ambroise Thomas.[147] Many of Beecham's later recordings of French music were made in Paris with the Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Française. "C'est un dieu", their concertmaster said of Beecham in 1957.[148][149]

Of the more than two dozen operas in the Verdi canon, Beecham conducted eight during his long career: Il trovatore, La traviata, Aida, Don Carlos, Rigoletto, Un ballo in maschera, Otello and Falstaff.[138] As early as 1904, Beecham met Puccini through the librettist Luigi Illica, who had written the libretto for Beecham's youthful attempt at composing an Italian opera.[150] At the time of their meeting, Puccini and Illica were revising Madama Butterfly after its disastrous première. Beecham rarely conducted that work, but he conducted Tosca, Turandot and La bohème.[151] His 1956 recording of La bohème, with Victoria de los Ángeles and Jussi Björling, has seldom been out of the catalogues since its release[152] and received more votes than any other operatic set in a 1967 symposium of prominent critics.[153]

Delius, Sibelius and "Lollipops"

[edit]

Except for Delius, Beecham was generally antipathetic to, or at best lukewarm about, the music of his native land and its leading composers.[154] Beecham's championship of Delius, however, promoted the composer from relative obscurity.[155] Delius's amanuensis, Eric Fenby, referred to Beecham as "excelling all others in the music of Delius ... Groves and Sargent may have matched him in the great choruses of A Mass of Life, but in all else Beecham was matchless, especially with the orchestra."[156] In an all-Delius concert in June 1911 Beecham conducted the premiere of Songs of Sunset. He put on Delius Festivals in 1929 and 1946[157] and presented his concert works throughout his career.[158] He conducted the British premieres of the operas A Village Romeo and Juliet in 1910 and Koanga in 1935, and the world premiere of Irmelin in 1953.[159] However, he was not an uncritical Delian: he never conducted the Requiem, and he detailed his criticisms of it in his book on Delius.[n 11]

Another major 20th-century composer who engaged Beecham's sympathies was Sibelius, who recognised him as a fine conductor of his music (although Sibelius tended to be lavish with praise of anybody who conducted his music).[161] In a live recording of a December 1954 concert performance of Sibelius's Second Symphony with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the Festival Hall, Beecham can be heard uttering encouraging shouts at the orchestra at climactic moments.[162]

Beecham was dismissive of some of the established classics, saying for example, "I would give the whole of Bach's Brandenburg Concertos for Massenet's Manon, and would think I had vastly profited by the exchange".[163] He was, by contrast, famous for presenting slight pieces as encores, which he called "lollipops". Some of the best-known were Berlioz's Danse des sylphes; Chabrier's Joyeuse Marche and Gounod's Le Sommeil de Juliette.[164]

Recordings

[edit]The composer Richard Arnell wrote that Beecham preferred making records to giving concerts: "He told me that audiences got in the way of music-making – he was apt to catch someone's eye in the front row."[165] The conductor and critic Trevor Harvey wrote in The Gramophone, however, that studio recordings could never recapture the thrill of Beecham performing live in the concert hall.[n 12]

Beecham began making recordings in 1910, when the acoustical process obliged orchestras to use only principal instruments, placed as close to the recording horn as possible. His first recordings, for HMV, were of excerpts from Offenbach's The Tales of Hoffmann and Johann Strauss's Die Fledermaus. In 1915, Beecham began recording for the Columbia Graphophone Company. Electrical recording technology (introduced in 1925–26) made it possible to record a full orchestra with much greater frequency range, and Beecham quickly embraced the new medium. Longer scores had to be broken into four-minute segments to fit on 12-inch 78-rpm discs, but Beecham was not averse to recording piecemeal – his well-known 1932 disc of Chabrier's España was recorded in two sessions three weeks apart.[167] Beecham recorded many of his favourite works several times, taking advantage of improved technology over the decades.[168]

From 1926 to 1932, Beecham made more than 70 discs, including an English version of Gounod's Faust and the first of three recordings of Handel's Messiah.[169] He began recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1933, making more than 150 discs for Columbia, including music by Mozart, Rossini, Berlioz, Wagner, Handel, Beethoven, Brahms, Debussy and Delius.[59] Among the most prominent of his pre-war recordings was the first complete recording of Mozart's The Magic Flute with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, made for HMV and supervised by Walter Legge in Berlin in 1937–38, a set described by Alan Blyth in Gramophone magazine in 2006 as having "a legendary status".[170] In 1936, during his German tour with the LPO, Beecham conducted the world's first orchestral recording on magnetic tape, made at Ludwigshafen, the home of BASF, the company that developed the process.[171]

During his stay in the US and afterwards, Beecham recorded for American Columbia Records and RCA Victor. His RCA recordings include major works that he did not subsequently re-record for the gramophone, including Beethoven's Fourth, Sibelius's Sixth and Mendelssohn's Reformation Symphonies.[172] Some of his RCA recordings were issued only in the US, including Mozart's Symphony No. 27, K199, the overtures to Smetana's The Bartered Bride and Mozart's La clemenza di Tito, the Sinfonia from Bach's Christmas Oratorio,[172] a 1947–48 complete recording of Gounod's Faust, and an RPO studio version of Sibelius's Second Symphony.[172] Beecham's RCA records that were released on both sides of the Atlantic were his celebrated 1956 complete recording of Puccini's La bohème[173] and an extravagantly rescored set of Handel's Messiah.[174] The former remains a top recommendation among reviewers,[175] and the latter was described by Gramophone as "an irresistible outrage … huge fun".[169]

For the Columbia label, Beecham recorded his last, or only, versions of many works by Delius, including A Mass of Life, Appalachia, North Country Sketches, An Arabesque, Paris and Eventyr.[172] Other Columbia recordings from the early 1950s include Beethoven's Eroica, Pastoral and Eighth symphonies, Mendelssohn's Italian symphony, and the Brahms Violin Concerto with Isaac Stern.[172]

From his return to England at the end of the Second World War until his final recordings in 1959, Beecham continued his early association with HMV and British Columbia, who had merged to form EMI. From 1955 his EMI recordings made in London were recorded in stereo. He also recorded in Paris, with his own RPO and with the Orchestra National de la Radiodiffusion Française, though the Paris recordings were in mono until 1958.[117] For EMI, Beecham recorded two complete operas in stereo, Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Carmen.[176] His last recordings were made in Paris in December 1959.[23] Beecham's EMI recordings have been continually reissued on LP and CD. In 2011, to mark the 50th anniversary of Beecham's death, EMI released 34 CDs of his recordings of music from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, including works by Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Richard Strauss and Delius, and many of the French "lollipops" with which he was associated.[177]

Relations with others

[edit]Beecham's relations with fellow British conductors were not always cordial. Sir Henry Wood regarded him as an upstart and was envious of his success;[178] the scrupulous Sir Adrian Boult found him "repulsive" as a man and a musician;[179] and Sir John Barbirolli mistrusted him.[180] Sir Malcolm Sargent worked with him in founding the London Philharmonic and was a friend and ally, but he was the subject of unkind, though witty, digs from Beecham who, for example, described the image-conscious Herbert von Karajan as "a kind of musical Malcolm Sargent".[181] Beecham's relations with foreign conductors were often excellent. He did not get on well with Arturo Toscanini,[182] but he liked and encouraged Wilhelm Furtwängler,[183] admired Pierre Monteux,[184] fostered Rudolf Kempe as his successor with the RPO, and was admired by Fritz Reiner,[185] Otto Klemperer[186] and Karajan.[187]

Despite his lordly drawl, Beecham remained a Lancastrian at heart. "In my county, where I come from, we're all a bit vulgar, you know, but there is a certain heartiness – a sort of bonhomie about our vulgarity – which tides you over a lot of rough spots in the path. But in Yorkshire, in a spot of bother, they're so damn-set-in-their-ways that there's no doing anything with them!"[188]

Beecham has been much quoted. In 1929, the editor of a music journal wrote, "The stories gathered around Sir Thomas Beecham are innumerable. Wherever musicians come together, he is likely to be one of the topics of conversation. Everyone telling a Beecham story tries to imitate his manner and his tone of voice."[189] A book, Beecham Stories, was published in 1978 consisting entirely of his bons mots and anecdotes about him.[190] Some are variously attributed to Beecham or one or more other people, including Arnold Bax and Winston Churchill; Neville Cardus admitted to inventing some himself.[191][n 13] Among the Beecham lines that are reliably attributed are, "A musicologist is a man who can read music but can't hear it";[193] his maxim, "There are only two things requisite so far as the public is concerned for a good performance: that is for the orchestra to begin together and end together; in between it doesn't matter much";[194] and his remark at his 70th birthday celebrations after telegrams were read out from Strauss, Stravinsky and Sibelius: "Nothing from Mozart?"[195]

He was completely indifferent to mundane tasks such as correspondence, and was less than responsible with the property of others. On one occasion, two thousand unopened letters were discovered among his papers. Havergal Brian sent him three scores with a view to having them performed. One of them, the Second English Suite, was never returned and is now considered lost.[196][197]

Honours and commemorations

[edit]Beecham was knighted in 1916 and succeeded to the baronetcy on the death of his father later that year. In 1938 the President of France, Albert Lebrun, invested him with the Légion d'honneur.[198] In 1955, Beecham was presented with the Order of the White Rose of Finland.[199] He was a Commendatore of the Order of the Crown of Italy and was made a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour in the 1957 Queen's Birthday Honours.[200][201] He was an honorary Doctor of Music of the universities of Oxford, London, Manchester and Montreal.[200]

Beecham, by Caryl Brahms and Ned Sherrin, is a play celebrating the conductor and drawing on a large number of Beecham stories for its material. Its first production, in 1979, starred Timothy West in the title role. It was later adapted for television, starring West, with members of the Hallé Orchestra taking part in the action and playing pieces associated with Beecham.[202]

In 1980 the Royal Mail put Beecham's image on the 13½p postage stamp in a series portraying British conductors; the other three in the series depicted Wood, Sargent and Barbirolli.[203] The Sir Thomas Beecham Society preserves Beecham's legacy through its website and release of historic recordings.[204]

In 2012, Beecham was voted into the inaugural Gramophone magazine "Hall of Fame".[205]

Books by Beecham

[edit]Beecham's published books were:

- John Fletcher (The Romanes Lecture for 1956). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1956. OCLC 315928398.

- A Mingled Chime – Leaves from an Autobiography. London: Hutchinson. 1959. OCLC 3672200.

- Frederick Delius. London: Hutchinson. 1959. OCLC 730041374.

The last of these was reissued in 1975 by Severn House, London, with an introduction by Felix Aprahamian and a discography by Malcolm Walker, ISBN 0-7278-0073-6.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Beecham had first approached Charles Villiers Stanford, but Stanford did not take private pupils.[7] André Messager recommended Beecham to study with Moszkowski.[8]

- ^ Lucas concludes that Josephine Beecham was suffering from post-natal depression. As Joseph Beecham was found to be keeping a mistress, his wife was able to obtain a judicial separation, which removed Joseph's right to block her release from the hospital.[10]

- ^ Beecham told an interviewer in 1910 that he spent a year composing, and produced three operas – two in English and one in Italian – and "once spent three weeks in trying to compose the first movement of a sonata", which led him to conclude that composition was not his forte.[16]

- ^ The lines are put into Beecham's mouth in the 1980 play Beecham by Caryl Brahms and Ned Sherrin.

- ^ Of the other operas of Beecham's 1910 seasons, lesser-known pieces, such as A Village Romeo and Juliet (Delius), Hansel and Gretel, The Wreckers (Ethel Smyth), L'enfant prodigue and Pelléas and Mélisande (Debussy), Ivanhoe (Sullivan), Shamus O'Brien (Stanford), Muguette (Edmond de Misa), Werther (Massenet), Feuersnot (Richard Strauss) and A Summer Night (George Clutsam) outnumbered the more popular pieces, such as Wagner's The Flying Dutchman and Tristan und Isolde, Bizet's Carmen, Verdi's Rigoletto and five Mozart works: Così fan tutte, The Marriage of Figaro, Der Schauspieldirektor, Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Don Giovanni.[36]

- ^ According to the biographer John Lucas, Beecham had intended to insist on including the Mendelssohn symphony, but was dissuaded by his assistant, Berta Geissmar, a Jewish refugee from the Nazis.[71] Geissmar herself says that she simply passed on a message from the German foreign minister, and the decision was Beecham's.[72] Throughout the tour, the orchestra flouted the custom of playing the Nazi anthem before concerts.[73]

- ^ Colin Davis, Beecham's assistant for the Glyndebourne production, took on the Magic Flute performances, and Rafael Kubelík conducted the Berlioz.[97]

- ^ The Handel works on which Beecham drew included Admeto, Alcina, Ariodante, Clori, Tirsi e Fileno, Lotario, Il Parnasso in Festa, Il pastor fido, Radamisto, Rinaldo, Rodrigo, Serse, Teseo and The Triumph of Time and Truth.[115]

- ^ Beecham liked to claim that he introduced Così fan tutte to Britain.[122] In fact, although he gave its first British performance for decades at His Majesty's Theatre in 1910, it had been performed in London in 1811,[123][124] in 1818[125] and again by the St. George's Opera Company in 1873, attracting very favourable comment from The Times.[126] Beecham was, however, correct when he teased an American lecture audience that Così fan tutte did not appear in the US until "about thirteen years" after his London production.[122] The US premiere was in 1922.[123]

- ^ Beecham gave a "blazing" performance of it at a memorial concert for Arturo Toscanini in New York in January 1957.[133]

- ^ Beecham thought Delius's invention was not of the same level in the Requiem as in earlier large scale compositions, and that a non-Christian requiem was a miscalculation, particularly at the height of the First World War.[160]

- ^ Harvey, reviewing the live 1956 taping of Sibelius's Second Symphony released after Beecham's death, wrote, "It is in one way a sad record, for it reminds one all too vividly of those Beecham occasions which can never happen again and which nobody else seems to be able to provide with so electrifying an atmosphere. … [T]here are those half-strangled yelps that Beecham emitted at moments of stress and climax, which one took to mean 'play, you so-and-so's, play!' – and play the BBC Symphony Orchestra does, like blazes."[166]

- ^ A typical, and well known, Beecham story – which, like many Beecham stories, is much repeated but not reliably verified – is of his meeting a distinguished woman whose face was familiar but whose name he could not remember. After some preliminaries about the weather, and desperately racking his brain, he asked after her family:

- "My brother has been rather ill lately."

- "Ah, yes, your brother. I'm sorry to hear that. And, er, what is your brother doing at the moment?"

- "Well ... he's still King", replied Princess Victoria.[192]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Reid, p. 19

- ^ Lucas, p. 6

- ^ Reid, pp. 25–27

- ^ a b c Reid, p. 27

- ^ a b c d Jefferson, Alan. "Beecham, Sir Thomas, second baronet (1879–1961)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2016 (subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Lucas, p. 144

- ^ Lucas, pp. 12 and 18

- ^ Beecham (1959), p. 52

- ^ a b c Crichton, Ronald, and John Lucas. "Beecham, Sir Thomas", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 13 March 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ Lucas, p. 17

- ^ Reid, pp. 31–34

- ^ a b c Reid, p. 62

- ^ a b c Lucas, p. 20

- ^ Lucas, p. 22

- ^ Beecham (1959), p. 74

- ^ "Mr. Thomas Beecham", The Musical Times, October 1910, p. 630

- ^ Lucas, p. 32

- ^ Reid, p. 54

- ^ Jefferson, p. 32

- ^ Lucas, p. 24

- ^ Reid, p. 55

- ^ Reid, pp. 55–56

- ^ a b Salter, p. 4; and Procter-Gregg, pp. 37–38

- ^ Russell, p. 10

- ^ Reid, p. 50

- ^ a b Reid, p. 70

- ^ a b Reid, p. 71

- ^ Reid, pp. 70–71

- ^ Reid, p. 88

- ^ a b Reid, p. 98

- ^ Beecham (1959), p. 88

- ^ Reid, p. 97

- ^ Reid, p. 108

- ^ Reid, p. 96

- ^ Reid, p. 107

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 111–119

- ^ Canarina, p. 39

- ^ a b Reid, p. 123

- ^ Reid, p. 141

- ^ a b Reid, p. 142

- ^ Reid, p. 145

- ^ Reid, pp. 161–162

- ^ "The Honours List", The Times, 1 January 1916, p. 9

- ^ Lucas, p. 136

- ^ a b Reid, p. 181

- ^ Beecham (1959), p. 181

- ^ a b Beecham (1959), p. 142

- ^ "Covent Garden Estate: Sale of the Property to Sir Joseph Beecham", The Times, 7 July 1914, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Sheppard, F. H. W. (ed). "The Bedford Estate: The Sale of the Estate" Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Survey of London, Volume 36: Covent Garden (1970), pp. 48–52. Retrieved 14 March 2011

- ^ "Sir Thomas Beecham to Pay in Full: The Receiving Order Discharged", The Manchester Guardian, 29 March 1923, p. 10

- ^ Langford, Samuel. "The Hallé Concerts: Sir Thomas Beecham's Return", The Manchester Guardian, 16 March 1923, p.18

- ^ "Albert Hall Concert: Sir Thomas Beecham's Return", The Times, 9 April 1923, p. 10

- ^ Kennedy (1971), p. 138

- ^ Aldous, p. 68

- ^ Reid, p. 202

- ^ Morrison, p. 79

- ^ Russell, p. 135

- ^ Russell, p. 18

- ^ a b Jefferson, p. 89

- ^ Geissmar, p. 267

- ^ Jefferson, p. 171

- ^ Jefferson, p. 170

- ^ Jefferson, p. 173

- ^ Jefferson, p. 172

- ^ Jefferson, p. 175

- ^ Kennedy (1989), p. 174

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 178–190

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 178–190 and 197

- ^ Jefferson, p. 194

- ^ Russell, p. 39

- ^ Lucas, p. 231

- ^ Geissmar p. 233

- ^ Russell, p. 42

- ^ Lucas, p. 232

- ^ Reid, pp. 217–218

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 214–215

- ^ a b Lucas, p. 239

- ^ Reid, p. 218

- ^ Lucas, p. 240

- ^ Jefferson, p. 222

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 201

- ^ Reid, p. 230

- ^ a b c d Reid, p. 231

- ^ Reid, p. 232

- ^ Jenkins (2000), p. 5

- ^ Lucas, pp. 308–310

- ^ Kennedy (1971), p. 189

- ^ Stiff, Wilfred, quoted in Procter-Gregg, pp. 113–114

- ^ "CD Review", BBC Radio 3, 12 March 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2011

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 200

- ^ a b Reid, p. 236

- ^ Haltrecht, p. 106

- ^ Jefferson, p. 103

- ^ "Concerts", The Times, 13 and 29 September 18 and 25 October 1, 15 and 29 November and 6 December 1958

- ^ "Concerts", The Times, 19 and 21 January 1955

- ^ a b Reid, pp. 238–239

- ^ "Sudden Setback for Sir Thomas Beecham", The Times, 13 July 1960, p. 12; and "The Trojans Revived", The Times, 30 April 1960, p. 10

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 21 and 226–27

- ^ Reid, p. 244

- ^ Reid, p. 245

- ^ Lucas, p. 339

- ^ Lucas, pp. 11, 12 and 24

- ^ "The World of Music", The Illustrated London News, 30 September 1922, p. 514

- ^ Reid, pp. 112–120

- ^ a b Reid, p. 120

- ^ Obituary, The Times, 14 October 1977, p. 17

- ^ Reid, pp. 134–137

- ^ Jefferson, p. 39

- ^ Lucas, p. 212

- ^ Remembering Paul Strang (1933–2024), Trinity Laban, 4 April 2024

- ^ Reid, p. 220

- ^ Reid, p. 241

- ^ Beecham (1992), p. 5

- ^ a b c Jefferson, p. 236

- ^ Golding, pp 3–6; and Melville-Mason (Handel), pp. 4–5

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 14

- ^ a b Wigmore, Richard. "Haydn Symphonies", Gramophone, September 1993, p. 53

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 235–236

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 197

- ^ Jefferson, p. 238

- ^ Lucas, pp. 62–63

- ^ a b Procter-Gregg, p. 182.

- ^ a b Holden, p. 253

- ^ "King's Theatre", The Times, 7 May 1811, p. 4; and 29 June 1811, p. 2

- ^ "King's Theatre", The Times, 12 June 1818, p. 2; and 21 July 1818, p. 2

- ^ "St. George's Opera", The Times, 21 January 1873, p. 4

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 115 and 238

- ^ a b Cardus, p. 60

- ^ Jenkins (1988), p. 3; and "Search results: Beethoven/Thomas Beecham", WorldCat. Retrieved 2 May 2014

- ^ a b c Jefferson, p. 235

- ^ Cardus, p. 28

- ^ "Concerts", The Times, 19 January 1955

- ^ Lucas, p. 331

- ^ Beecham (1959), p. 81

- ^ Cardus, p. 109; Procter-Gregg, p. 77; and Melville-Mason (Wagner), p. 4

- ^ Reid, p. 206

- ^ Jefferson, p. 189

- ^ a b Procter-Gregg, p. 203

- ^ Howes, Frank, quoted in Procter-Gregg, p. 77

- ^ Greenfield, Edward. "Strauss, Richard. Ein Heldenleben", Gramophone, June 1961, p. 32

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 234–235

- ^ "Composer's Gift to Sir T. Beecham", The Times, 22 April 1938, p. 12

- ^ Atkins, p. 15

- ^ Lebrecht, Norman. "Hector Berlioz – the Unloved Genius" Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Lebrecht Weekly (La Scena Musicale), 10 December 2003. Retrieved 31 March 2008

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 196

- ^ Procter-Gregg, pp. 37–38

- ^ Procter-Gregg, pp. 196–203

- ^ Jenkins (2000), p. 3

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 39

- ^ Lucas, pp. 22–23 and 24–26. Jefferson (pp. 204–205) incorrectly gives the librettist's name as "Giuseppe Illica".

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 202

- ^ Jefferson, p. 200

- ^ March, pp. 62–63

- ^ Jefferson, pp. 230–233

- ^ Reid, pp. 56–61

- ^ Procter-Gregg, pp. 56–57

- ^ Lucas, pp. 187–189 and 316–18

- ^ Procter-Gregg, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Lucas, pp. 60, 223, and 329

- ^ Montgomery and Threlfall, p. 135

- ^ Osborne, p. 387

- ^ Originally issued on LP as HMV ALP 1947 in 1962 and subsequently reissued on compact disc as BBC Legends BBCL 415–4 in 2005

- ^ Cardus, p. 29

- ^ Jenkins (1991) pp. 4 and 12

- ^ Arnell, Richard. "Sir Thomas Beecham: Some Personal Memories", Tempo, Summer 1961, pp. 2–3 and 17. Retrieved 15 March 2011 (subscription required) Archived 24 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harvey, Trevor. "Sibelius, Symphony No. 2 in D major", Gramophone, November 1962, p. 38

- ^ Jenkins (1992), p. 3

- ^ Procter-Gregg, pp. 196–199

- ^ a b Blyth, Alan. "Music from Heaven", Gramophone, December 2003, p. 52

- ^ Blyth, Alan. "Masonic Magic", Gramophone, January 2006, p. 28

- ^ Borwick, John. "Commentary: 50 Years of (BASF) Tape", Gramophone, April 1984, p. 91. Retrieved 13 March 2011

- ^ a b c d e Jenkins, Lyndon. "The Beecham Archives", Gramophone, September 1987, p. 11

- ^ "Sir Thomas Beecham Selected Discography", Gramophone, May 2011, p. 11

- ^ Culshaw, p. 212

- ^ See, for instance, "CD Review: Building a Library Recommendations" Archived 27 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, 14 June 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2011; and "Sir Thomas Beecham Selected Discography", Gramophone, May 2001, p. 11

- ^ Vaughan, Denis. "Beecham in the Recording Studio: a centenary tribute to Sir Thomas Beecham", Gramophone, April 1979, p. 1

- ^ EMI (2011), "Sir Thomas Beecham Edition", catalogue numbers 9099462 Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 9099642 Archived 23 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 9186112 Archived 23 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine and 9099322

- ^ Jacobs, pp. 330–332

- ^ Kennedy (1989), p. 154

- ^ Jefferson, p. 183

- ^ Atkins, p. 61

- ^ Jefferson, p. 105

- ^ Jefferson, p. 179

- ^ Canarina, p. 291

- ^ Reid, p. 192

- ^ Klemperer, p.193

- ^ Osborne, p. 248

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 152

- ^ Grew, Sydney. "British Conductors", British Musician and Musical News, June 1929, p. 154

- ^ Atkins, passim

- ^ Cardus, p. 26

- ^ One of the many variants of this story is printed in Atkins, p. 89

- ^ Procter-Gregg, p. 154; and Cardus, p. 75

- ^ "Jolts and Jars: some wit and wisdom by Sir Thomas Beecham", The Listener, 3 October 1974; also heard on the EMI "Beecham in Rehearsal" disc, EMI CDM 7 64465 2 (1992)

- ^ Cardus, p. 125; and Atkins, p. 48

- ^ Charles Reid, Thomas Beecham: An Independent Biography, 1961, p. 93

- ^ The Havergal Brian Society Newsletter, No. 228, July–August 2013, p. 3, footnote 28. Retrieved 23 May 2016

- ^ Russell, p. 52

- ^ Lucas, p. 330

- ^ a b Jefferson, p. 101

- ^ "Sir T. Beecham made C.H.", The Times, 13 June 1957, p. 10

- ^ Timothy West as Beecham, BBC TV film, 1979, British Film Institute Film and TV database. Retrieved 26 July 2007

- ^ "Conductors on Stamps", The Times, 17 July 1980, p. 18

- ^ "Membership information" Archived 5 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Sir Thomas Beecham Society. Retrieved 30 March 2011

- ^ "Sir Thomas Beecham" Gramophone. Retrieved 10 April 2012

Sources

[edit]- Aldous, Richard (2001). Tunes of Glory: The Life of Malcolm Sargent. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-180131-1.

- Atkins, Harold; Archie Newman (1978). Beecham Stories. London: Robson Books. ISBN 0-86051-044-1.

- Beecham, Thomas (1959) [1943]. A Mingled Chime. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 470511334.

- Beecham, Thomas (1992). Notes to Messiah. London: RCA. RCA CD 09026-61266-2

- Canarina, John (2003). Pierre Monteux, Maître. Pompton Plains and Cambridge: Amadeus Press. ISBN 1-57467-082-4.

- Cardus, Neville (1961). Sir Thomas Beecham. London: Collins. OCLC 1290533.

- Culshaw, John (1981). Putting the Record Straight. London: Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-436-11802-5.

- Geissmar, Berta (1944). The Baton and the Jackboot. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Golding, Robin (1962). Notes to Love in Bath. London: EMI Records. EMI CD CDM 7-63374-2

- Haltrecht, Montague (1975). The Quiet Showman: Sir David Webster and the Royal Opera House. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211163-2.

- Holden, Amanda, ed. (1997). The Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051385-X.

- Jacobs, Arthur (1994). Henry J Wood. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-413-69340-6.

- Jefferson, Alan (1979). Sir Thomas Beecham: A Centenary Tribute. London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 0-354-04205-X.

- Jenkins, Lyndon (1988). Notes to Beecham Conducts Bizet. London: EMI Records. EMI CD 5-67231-2

- Jenkins, Lyndon (1992). Notes to French Favourites. London: EMI Records. EMI CD CDM 7 63401 2

- Jenkins, Lyndon (1991). Notes to Lollipops. London: EMI Records. EMI CD CDM 7-63412-2

- Jenkins, Lyndon (2000). Notes to Mozart and Beethoven Symphonies. London: EMI Records. EMI CD 5-67231-2

- Kennedy, Michael (1989). Adrian Boult. London: Papermac. ISBN 0-333-48752-4.

- Kennedy, Michael (1971). Barbirolli, Conductor Laureate: The Authorised Biography. London: MacGibbon and Key. ISBN 0-261-63336-8.

- Klemperer, Otto (1986). Klemperer on Music: Shavings from a Musician's Workbench. London: Toccata Press. ISBN 0-907689-13-2.

- Lucas, John (2008). Thomas Beecham: An Obsession with Music. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-402-1.

- March, Ivan, ed. (1967). The Great Records. Blackpool: Long Playing Record Library. OCLC 555041974.

- Melville-Mason, Graham (2002). Notes to Sir Thomas Beecham conducts Handel and Goldmark. London: Sony Records. Sony CD SMK87780

- Melville-Mason, Graham (2002). Notes to Sir Thomas Beecham conducts Wagner. London: Sony Records. Sony CD SMK89889

- Montgomery, Robert; Robert Threlfall (2007). Music and Copyright: the case of Delius and his publishers. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5846-5.

- Morrison, Richard (2004). Orchestra – The LSO: A Century of Triumph and Turbulence. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-21584-X.

- Osborne, Richard (1998). Herbert von Karajan: A Life in Music. London: Chatto and Windus. ISBN 1-85619-763-8.

- Procter-Gregg, Humphrey, ed. (1976). Beecham Remembered. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1117-8.

- Reid, Charles (1961). Thomas Beecham: An Independent Biography. London: Victor Gollancz. OCLC 500565141.

- Russell, Thomas (1945). Philharmonic Decade. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 504109856.

- Salter, Lionel (1991). Notes to Franck and Lalo Symphonies. London: EMI Records. EMI CD CDM-7-63396-2

External links

[edit]Thomas Beecham

View on GrokipediaSir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet (29 April 1879 – 8 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario who founded the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 1932 and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in 1946.[1][2] Born in St Helens, Lancashire, to the industrialist Joseph Beecham, he drew on inherited wealth to finance musical ventures, including early orchestras like the Beecham Symphony Orchestra in 1909.[2] Knighted in 1916 and later made Companion of Honour in 1957, Beecham debuted as a conductor at age 20 and produced over 120 operas, introducing 60 to England for the first time.[2] Beecham championed composers such as Frederick Delius, Richard Strauss, and Jules Massenet, premiering Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier in Britain in 1913 and bringing Russian ballet and opera to London audiences.[1][3] His interpretations emphasized vitality and flair, often prioritizing instinct over scholarly precision, which led to acclaimed performances of Mozart, Wagner, and Strauss works across Europe and during a successful 1950 tour of the United States with the Royal Philharmonic.[1][3] Renowned for his wit, oratory, and controversial stances— including clashes with musical institutions and tax authorities that prompted periods abroad—Beecham shaped British musical life through personal fortune and impresarial drive, though his temperamental style and institutional critiques drew resentment.[1][3] He continued conducting until near his death from coronary thrombosis, leaving a legacy of orchestral innovation and recorded performances that advanced English music's global reach.[1]