Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

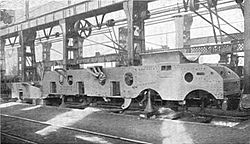

Locomotive frame

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (May 2024) |

A locomotive frame is the structure that forms the backbone of the railway locomotive, giving it strength and supporting the superstructure elements such as a cab, boiler or bodywork. The vast majority of locomotives have had a frame structure of some kind. The frame may in turn be supported by axles directly attached to it, or it may be mounted on bogies (known as trucks in American English), or a combination of the two. The bogies in turn will have frames of their own.

Types of frame

[edit]

Three main types of frame on steam locomotives may be distinguished:[1]

Plate frames

[edit]These used steel plates about 1–2 in (25.4–50.8 mm) thick. They were mainly used in Britain and continental Europe. On most locomotives, the frames would be situated within the driving wheels ("inside frames"), but some classes of an early steam locomotive and diesel shunters were constructed with "outside frames". Some early designs were double framed where the frame consisted of plates both inside and outside the driving wheels. Others were sandwich frames where the frame was constructed of wood sandwiched between two metal plates.

Bar frames

[edit]

These are openwork girder structures built up from steel or iron bars which are usually 4–7 in (100–180 mm) thick, welded into a single load-bearing assembly. They were first used on the Bury Bar Frame locomotive during the 1830s, and were widely used in nineteenth century American locomotives (including those exported to Australia and New Zealand; see Vogel railways).

Cast steel beds

[edit]Cast steel locomotive beds were developed in the latter years of steam locomotive design in the United States, from where they were also exported to Britain and Australia.

Articulated locomotives

[edit]An articulated locomotive with no fixed wheels (i.e. excluding the Mallet locomotive but including other articulated steam locomotives, as well as most diesel and electric locomotives) may have a separate frame beneath the superstructure, or the bodywork's internal structure may be load-bearing. Rarely is a true monocoque structure used.

Diesel and electric locomotives with a traditional, full-width body, known as cab units in North America, tend to have their strength in an internal structure. This style of construction is still popular elsewhere, but North American locomotives nowadays are overwhelmingly hood units—with a strong frame beneath the superstructure that carries all the load, and bodywork made of removable panels for easy maintenance. Fully enclosed locomotives are used in some limited applications, mostly for passenger trains. These tend to be cowl units, in which the body is not load-bearing.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ransome-Wallis, P. (1959). Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Railway Locomotives (2001 republication ed.). Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-41247-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help), p 255.

.jpg/250px-Frames_in_position,_Pacific_construction_at_Doncaster_works_(CJ_Allen,_Steel_Highway,_1928).jpg)

.jpg)