Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

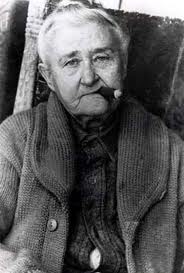

Poker Alice

View on Wikipedia

Alice Ivers Duffield Tubbs Huckert (17 February 1851 – 27 February 1930), better known as Poker Alice, Poker Alice Ivers, or Poker Alice Tubbs, was an English-born American gambler, brothel owner, and rancher who became known for playing poker[1][2] and faro[3][4] in the Wild West.

Key Information

Born in Devonshire to Irish parents, Ivers moved with her family to Virginia at the age of 12. As an adult, she moved to Leadville, Colorado, where she met her first husband Frank Duffield. He got her interested in poker, but was killed a few years after they married. She made a name for herself by winning money from poker games in places like Silver City, New Mexico, and worked at a saloon in Creede, Colorado, which was owned by Jesse James' killer Robert Ford.[5]

Early life

[edit]Alice Ivers was born in Devonshire on 17 February 1851,[6] the daughter of Irish immigrants.[7] Her family moved to Virginia when she was 12. As a young woman, she went to boarding school in Virginia to become a refined lady. In her late teens, her family moved to Leadville, Colorado.[8]

Personal life

[edit]

It was in Leadville that Ivers met Frank Duffield, whom she married[6] at a young age. Frank was a mining engineer who played poker in his spare time.[7] After just a few years of marriage, Frank was killed in an accident[7] while resetting a dynamite charge in a Leadville mine.[9] Ivers was known for splurging her winnings, such as when she won a lot of money in Silver City, New Mexico, only to spend it all in New York City. After all of her big wins, she would travel to New York and spend her money on clothes. She was very keen on keeping up with the latest fashion and would buy dresses to wear at poker games, partly as a business investment to distract her opponents.[9]

Ivers met her next husband Warren G. Tubbs around 1890,[6] when they were both dealers at Bedrock Tom's saloon in Deadwood, South Dakota.[8] A drunken miner tried to attack Warren with a knife, causing her to threaten the miner with her .38 firearm.[10] After this incident, she started a romance with Warren and they were soon married.[8] Some sources report they had had seven children together.[11][12] Other sources report they did not have any children together, but that she brought a daughter and a son into the marriage, giving Warren two stepchildren.[13] Her son, George, would take on the Tubbs name. In 1934, George was saved from a train after he was found lying on the tracks. Two women were able to pull him to safety just in time to save his life. At the time of the incident, he was 65 years old, putting his birth around 1868.[14]

Warren was a painter by trade, and it was speculated that he contracted tuberculosis through his work. For the last years of his life, Ivers tried to help him regain his health. A few months before he died, she moved him to a ranch on the Moreau River, 100 miles (160 km) from Sturgis, South Dakota, where he died on 31 December 1909.[15][16][17] To secure a proper burial and funeral, Ivers wrapped his body in blankets, placed him in their lumber wagon, and traveled to Sturgis with her team of horses. It took her four days to travel along the snow-covered trails to Sturgis, where she was able to arrange a funeral for Warren. In order to pay the funeral costs, she traveled to Rapid City, South Dakota, where she worked as a bartender at Black Nell's resort.[18]

Her third husband was George Huckert,[10] who worked on her homestead and took care of the sheep.[19] He was constantly proposing to her, and she eventually came to owe him $1,008 but married him instead, figuring that it would be cheaper than paying his back wages.[10] Huckert died on 12 October 1924.[20]

Poker career

[edit]After the death of her first husband, Ivers started to play poker seriously.[7] She was in a tough financial position. After failing in a few different jobs including teaching, she turned to poker to support herself financially.[19] She would make money by gambling and working as a dealer. She made a name for herself by winning money from poker games.[7] By the time she was given the nickname "Poker Alice",[8] she was drawing in large crowds to watch her play and men were constantly challenging her to play. Saloon owners liked that she was a respectable woman who kept to her values, including her refusal to play poker on Sundays.[10]

As Ivers' reputation grew, so did the amount of money she was making. Some nights she would make $6,000,[10] an incredibly large sum of money at the time. She claimed that she won $250,000, which would now be worth more than $3 million.[citation needed] She used her good looks to distract men at the poker table. She always had the newest dresses,[9] and even in her 50s was considered a very attractive woman. She was also very good at counting cards and figuring odds, which helped her at the table.[21]

Alice was known to have always carried a gun with her, preferably her .38, and frequently smoked cigars.[22]

Resort and jail time

[edit]After Warren's death, Ivers eventually purchased a building on the south side of Bear Butte Creek, between the city of Sturgis and Fort Meade, where the current Sturgis City Park now stands.[23] Poker Alice's resort, as it was commonly known, gained notoriety in 1913 due to a confrontation between soldiers of Troop K stationed at Fort Meade and Ivers herself.[24]

Trouble had initially developed between the soldiers and Ivers in the early part of July 1913, a little over a week before the shooting. Later that week, the trouble was rekindled, and finally once again on 14 July.[25] Around 10:30 pm, five soldiers of Troop K, accompanied by a number of members of the South Dakota guard that had recently been stationed at Fort Meade, went to Ivers' resort for the intention of starting a "rough house". After the soldiers were refused admittance, they began throwing stones through the windows of Ivers' resort and cutting telephone and electric wires. In response, Ivers opened fire, landing five shots. One struck Private Fred Koetzle of Troop K in the head, and he died from the wound at around midnight.[26] Another soldier, 22-year-old Joseph C. Miner, was also shot, the bullet passing three inches above his heart. While he was initially expected to also die from his wounds, he later recovered.[27] Three other individuals were also struck, including a civilian.[28]

Immediately following the shooting, police, the sheriff and his deputies arrived at the scene. Ivers, along with six of her girls, were placed under arrest and sent to the county jail.[29] No charges were filed by State's Attorney Gray of Meade County against Ivers for the shooting and subsequent death of Koetzle. After investigating the facts of that night, it was determined that Ivers was justified in the shooting, as she was defending or attempting to defend her personal property. However, she was charged with keeping a house of "ill fame" and her six girls (Jennie Palmer, Bessie Brundidge, Ann Carr, Birdie Harris, Mabel Smith, and Edith Brown) were convicted of frequenting a house of "ill fame".[30]

Two years later, another confrontation at Poker Alice's resort led to the shooting of several soldiers and one civilian. Private Cadwell was shot in the abdominal region, Private Wood in the neck, and an unnamed civilian in the arm. The incident was written off as a "booze" fight.[31] Ivers continued to have run-ins with the law, culminating in the 1920s. In 1924, her resort was raided for bootlegging.[32] The following year, her resort was raided, possibly for the last time, and she was charged and convicted of operating a house of prostitution.[33]

In 1928, facing time in the state penitentiary for her convictions of bootlegging and running a house of prostitution, Ivers' community came together to petition the governor to grant her a pardon. The claim made was that Ivers was in poor health, and confinement to prison could be fatal for her. Hundreds signed the petition.[34] On 20 December 1928, the pardon was granted by Governor William J. Bulow.[35] After being pardoned, Ivers appears to have retired and no future run-ins with the law would be reported.[citation needed]

Death

[edit]On 6 February 1930, Ivers underwent a gallbladder operation in Rapid City, South Dakota. There was a general fear that recovery would be difficult due to her advanced age, but it appeared just two days later that she was recovering speedily and she was expected to be able to return home before long.[36] Her recovery continued, but doctors warned that there was no surety she was out of danger.[37] She died on 27 February.[38]

Funeral services were held for Ivers on 1 March 1930 at the St. Aloysius Cemetery in Sturgis, South Dakota, where she was buried. Father Columban of the Catholic Church gave a sermon at her grave.[39] When her will was read, it was revealed that she had disinherited her relatives for ignoring her in her declining years, and had instead divided her estate among her friends.[40][41]

Legacy

[edit]- In 1960, Barbara Stuart played Poker Alice in a three-part episode of The Texan.

- Ivers has been fictionalized in several films, including the television films The New Maverick (in which she was played by Susan Sullivan) and Poker Alice (in which she was played by Elizabeth Taylor).[42]

- Ivers is mentioned as one of the legends of the Wild West on the Lucky Luke album Calamity Jane.

- Poker Alice was the name used by an English indie rock band from Stratford-upon-Avon in the 1990s.

References

[edit]- ^ ""Poker" Alice Tubbs (1851-1930)". Denver Public Library History. 10 December 2018. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Trimble, Marshall (27 September 2017). "Poker Alice". True West Magazine. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Cooper, Courtney Ryley (3 December 1927). "Easy Come, Easy Go". Saturday Evening Post. Curtis Publishing Company.

- ^ "Queen of Faro Camps to see World Series". Rapid City Journal. 5 October 1929.

- ^ "Poker Alice – Famous Frontier Gambler". Legends of America. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- ^ a b c Lackmann, Ronald W. (1 January 1997). Women of the Western Frontier in Fact, Fiction, and Film. McFarland. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-7864-0400-1.

- ^ a b c d e Sharpe, Graham (5 March 2015). Poker's Strangest Hands. Portico. p. 1928. ISBN 978-1-910232-31-6.

- ^ a b c d Williamson, G. R. (15 May 2012). Frontier Gambling. G.R. Williamson. ISBN 978-0-9852780-1-4.

- ^ a b c Rutter, Michael (26 November 2012). Upstairs Girls: Prostitution in the American West. Farcountry Press. ISBN 978-1-56037-542-5.

- ^ a b c d e Sharpe, Graham (5 March 2015). Poker's Strangest Hands. Portico. p. 1929. ISBN 978-1-910232-31-6.

- ^ Harris, Martin (23 June 2019). Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game. D&B Publishing. ISBN 978-1-912862-00-9.

- ^ Wallis, Michael; McCubbin, Robert (1 May 2011). The Wild West: 365 Days. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-61312-144-3.

- ^ "Warren Tubbs". Black Hills Press. 3 January 1909.

- ^ "Son of Notorious Hills Character Saved from Train". Argus-Leader. 14 April 1934.

- ^ Soldat, Kate (21 June 1953). "Poker Alice's Career Had Pathetic, Stormy Events". Rapid City Journal.

- ^ "Warren Tubbs". Black Hills Press. 3 January 1910.

- ^ South Dakota Department of Health. Index to South Dakota Death Records, 1905-1955. Pierre, SD, USA: South Dakota Department of Health. Certificate no. 19024

- ^ Soldat, Kate (21 June 1953). "Poker Alice's Career Had Pathetic, Stormy Events". Rap.

- ^ a b Yadon, Laurence (23 September 2010). 100 Oklahoma Outlaws, Gangsters & Lawmen. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4556-0004-5.

- ^ South Dakota Department of Health. Index to South Dakota Death Records, 1905-1955. Pierre, SD, USA: South Dakota Department of Health. Certificate Number 94153 Page Number 434

- ^ Fifer, Barbara C. (1 April 2008). Bad Boys of the Black Hills: And Some Wild Women, Too. Farcountry Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-56037-548-7.

- ^ Fifer, Barbara C. (1 April 2008). Bad Boys of the Black Hills: And Some Wild Women, Too. Farcountry Press. pp. 152, 154. ISBN 978-1-56037-548-7.

- ^ Holland, Debra (26 January 1987). "Sturgis Debates Saving Historic House". Rapid City Journal.

- ^ "Poker Alice ' Resort at Sturgis Raided". Rapid City Journal. 10 June 1924.

- ^ "Two Soldiers Shot; One Dead". The Mitchell Capital. 17 July 1913.

- ^ ""Poker Alice," Dive Keeper at Sturgis Kills Soldier Wounds Five Others". Rapid City Journal. 16 July 1913.

- ^ "Fatal Shooting At Sturgis Monday". The Daily Deadwood Pioneer-Times. 16 July 1913.

- ^ ""Poker Alice," Dive Keeper at Sturgis Kills Soldier Wounds Five Others". Rapid City Journal. 16 July 1913.

- ^ ""Poker Alice," Dive Keeper at Sturgis Kills Soldier Wounds Five Others". Rapid City Journal. 16 July 1913.

- ^ "Will not be tried for killing of Koetzle". The Weekly Pioneer Times Mining Review. 17 July 1913.

- ^ "Spicy Sturgis Stories". Lead Daily Call. 12 October 1915.

- ^ "Poker Alice ' Resort at Sturgis Raided". Lead Daily Call. 10 June 1924.

- ^ "Seven in Ten Convicted at Meade County Court". Argus-Leader. 22 October 1925.

- ^ "'Poker Alice' Seeks Pardon". Argus. 14 November 1928.

- ^ "Poker Alice Given Pardon". Lead. 20 December 1928.

- ^ "Condition of "Poker Alice" is Improved". The Black Hills Weekly. 8 February 1930.

- ^ "Poker Alice is Recovering From Gall Stone Operation". Argus-Leader. 15 February 1930.

- ^ "Poker Alice Dies in Rapid City Today". The Black Hills Weekly. 27 February 1930.

- ^ "Cold Winds Sweep Cemetery As 'Poker Alice' is Buried". Argus-Leader. 2 March 1930.

- ^ "Poker Alice Divides Estate Among Friends". The Daily Plainsman. 4 March 1930.

- ^ Mumey, Nolie (1951). "Last Will and Testament". Poker Alice. Denver, Col: Artcraft Press. p. 45-47.

- ^ Lackmann, Ronald W. (1 January 1997). Women of the Western Frontier in Fact, Fiction, and Film. McFarland. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-7864-0400-1.