Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Poxviridae

View on Wikipedia

| Poxviridae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Varidnaviria |

| Kingdom: | Bamfordvirae |

| Phylum: | Nucleocytoviricota |

| Class: | Pokkesviricetes |

| Order: | Chitovirales |

| Family: | Poxviridae |

| Subfamilies | |

Poxviridae is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. The family contains 22 genera that are assigned to two subfamilies: Chordopoxvirinae and Entomopoxvirinae. Entomopoxvirinae infect insects and Chordopoxvirinae infect vertebrates. Diseases associated with this family include smallpox.[1][2]

Four genera of poxviruses can infect humans: Orthopoxvirus, Parapoxvirus, Yatapoxvirus, Molluscipoxvirus. Orthopoxvirus: smallpox virus (variola), vaccinia virus, cowpox virus, Mpox virus; Parapoxvirus: orf virus, pseudocowpox, bovine papular stomatitis virus; Yatapoxvirus: tanapox virus, yaba monkey tumor virus; Molluscipoxvirus: molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV).[3] The most common are vaccinia (seen on the Indian subcontinent)[citation needed] and molluscum contagiosum, but Mpox infections are rising (seen in west and central African rainforest countries). The similarly named disease chickenpox is not a true poxvirus and is caused by the herpesvirus, varicella zoster. Parapoxvirus and orthopoxvirus genera are zoonotic.

Etymology

[edit]The name of the family, Poxviridae, is a legacy of the original grouping of viruses associated with diseases that produced poxes on the skin. Modern viral classification is based on phenotypic characteristics; morphology, nucleic acid type, mode of replication, host organisms, and the type of disease they cause. The smallpox virus remains the most notable member of the family.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

Diseases caused by pox viruses, especially smallpox, have been known about for centuries. One of the earliest suspected cases is that of Egyptian pharaoh Ramses V who is thought to have died from smallpox circa 1150 years BCE.[4][5] Smallpox was thought to have been transferred to Europe around the early 8th century and then to the Americas in the early 16th century, resulting in the deaths of 3.2 million Aztecs within two years of introduction. This death toll can be attributed to the indigenous population's complete lack of exposure to the virus over millennia.[citation needed]

A century after Edward Jenner showed that the less potent cowpox could be used to effectively vaccinate against the more deadly smallpox, a worldwide effort to vaccinate everyone against smallpox began with the ultimate goal to rid the world of the plague-like epidemic.[citation needed] The last case of endemic smallpox occurred in Somalia in 1977. Extensive searches over two years detected no further cases, and in 1979 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the disease officially eradicated.[citation needed]

In 1986, all virus samples were destroyed or transferred to two approved WHO reference labs: at the headquarters of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (the C.D.C.) in Atlanta, Georgia (the United States) and at the Institute of Virus Preparations in Moscow.[6] After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the American and UK governments have had increased concern over the use of smallpox, or a smallpox-like disease, in bioterrorism. However, several poxviruses including vaccinia virus, myxoma virus, tanapox virus and raccoon pox virus are currently being investigated for their therapeutic potential in various human cancers in preclinical and clinical studies.[7][8][9]

Microbiology

[edit]Structure

[edit]

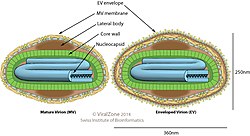

Poxviridae viral particles (virions) are generally enveloped (external enveloped virion), though the intracellular mature virion form of the virus, which contains different envelope, is also infectious. They vary in their shape depending upon the species but are generally shaped like a brick or as an oval form similar to a rounded brick because they are wrapped by the endoplasmic reticulum. The virion is exceptionally large, its size is around 200 nm in diameter and 300 nm in length and carries its genome in a single, linear, double-stranded segment of DNA.[10] By comparison, rhinoviruses are 1/10 as large as a typical Poxviridae virion.[11] On the outer surface membrane it has randomly arranged tubules.

Genome

[edit]Phylogenetic analysis of 26 different chordopoxvirus genomes has shown that the central region of the genome is conserved and contains ~90 genes.[12] The termini in contrast are not conserved between species. Of this group Avipoxvirus is the most divergent. The next most divergent is Molluscipoxvirus. Capripoxvirus, Leporipoxvirus, Suipoxvirus and Yatapoxvirus genera cluster together: Capripoxvirus and Suipoxvirus share a common ancestor and are distinct from the genus Orthopoxvirus. Within the Othopoxvirus genus Cowpox virus strain Brighton Red, Ectromelia virus and Mpox virus do not group closely with any other member. Variola virus and Camelpox virus form a subgroup. Vaccinia virus is most closely related to CPV-GRI-90.[citation needed]

The GC-content of family member genomes differ considerably.[13] Avipoxvirus, capripoxvirus, cervidpoxvirus, orthopoxvirus, suipoxvirus, yatapoxvirus and one Entomopox genus (Betaentomopoxvirus) along with several other unclassified Entomopoxviruses have a low G+C content while others - Molluscipoxvirus, Orthopoxvirus, Parapoxvirus and some unclassified Chordopoxvirus - have a relatively high G+C content. The reasons for these differences are not known.[citation needed]

Replication

[edit]

Replication of the poxvirus involves several stages.[14] The replication can be divided into early, intermediate and late phase. The virus first binds to a receptor on the host cell surface; the receptors for the poxvirus are thought to be glycosaminoglycans.[citation needed] After binding to the receptor, the virus enters the cell where it uncoats.[citation needed] Uncoating of the virus is a two step process.[citation needed] Firstly the outer membrane is removed as the particle enters the cell; secondly the virus particle (without the outer membrane) fuses with the cellular membrane to release the core into the cytoplasm.[citation needed] The pox viral genes are expressed in two phases.[citation needed] The early genes encode the non-structural protein, including proteins necessary for replication of the viral genome, and are expressed before the genome is replicated.[citation needed] The late genes are expressed after the genome has been replicated and encode the structural proteins to make the virus particle.[citation needed] The assembly of the virus particle occurs in five stages of maturation that lead to the final exocytosis of the new enveloped virion.[citation needed] After the genome has been replicated, the immature virion assembles the A5 protein to create the intracellular mature virion.[citation needed] The protein aligns and the brick-shaped envelope of the intracellular enveloped virion.[citation needed] These particles are then fused to the cell plasma to form the cell-associated enveloped virion, which encounters the microtubules and prepares to exit the cell as an extracellular enveloped virion.[citation needed] The assembly of the virus particle occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell and is a complex process that is currently being researched to understand each stage in more depth.[citation needed] Considering the fact that this virus is large and complex, replication is relatively quick taking approximately 12 hours until the host cell dies by the release of viruses.[citation needed]

The replication of poxvirus is unusual for a virus with double-stranded DNA genome because it occurs in the cytoplasm,[15] although this is typical of other large DNA viruses.[16] Poxvirus encodes its own machinery for genome transcription, a DNA dependent RNA polymerase,[17] which makes replication in the cytoplasm possible. Most double-stranded DNA viruses require the host cell's DNA-dependent RNA polymerase to perform transcription. These host polymerases are found in the nucleus, and therefore most double-stranded DNA viruses carry out a part of their infection cycle within the host cell's nucleus.[citation needed]

The intermediate phase of replication is critical because, on that stage, the virus affects the host's normal function and modifies it more optimally to itself. For example, the virus can inhibit host apoptosis and block the antiviral state. On the replication, poxviruses have their enzymes for example vaccinia virus has decapping enzymes D9 and D10. Decapping enzymes that belong to the Nudix hydrolase superfamily those it used to remove mRNA 5'cap from viral and host mRNA. By removing 5'cap from the mRNA the virus reduces the accumulation of viral dsRNA and inhibit immune response.

Evolution

[edit]

The ancestor of the poxviruses is not known but structural studies suggest it may have been an adenovirus or a species related to both the poxviruses and the adenoviruses.[18]

Based on the genome organisation and DNA replication mechanism a phylogenetic relationships may exist between the rudiviruses (Rudiviridae) and the large eukaryal DNA viruses: the African swine fever virus (Asfarviridae), Chlorella viruses (Phycodnaviridae) and poxviruses (Poxviridae).[19]

The mutation rate in poxvirus genomes has been estimated to be 0.9–1.2 x 10−6 substitutions per site per year.[20] A second estimate puts this rate at 0.5–7 × 10−6 nucleotide substitutions per site per year.[21] A third estimate places the rate at 4–6 × 10−6.[22]

The last common ancestor of the extant poxviruses that infect vertebrates existed 0.5 million years ago. The genus Avipoxvirus diverged from the ancestor 249 ± 69 thousand years ago. The ancestor of the genus Orthopoxvirus was next to diverge from the other clades at 0.3 million years ago. A second estimate of this divergence time places this event at 166,000 ± 43,000 years ago.[21] The division of the Orthopoxvirus into the extant genera occurred ~14,000 years ago. The genus Leporipoxvirus diverged ~137,000 ± 35,000 years ago. This was followed by the ancestor of the genus Yatapoxvirus. The last common ancestor of the Capripoxvirus and Suipoxvirus diverged 111,000 ± 29,000 years ago.[citation needed]

An isolate from a fish – salmon gill poxvirus – appears to be the earliest branch in the Chordopoxvirinae.[23] A new systematic has been proposed recently after findings of a new squirrel poxvirus in Berlin, Germany.[24]

Smallpox

[edit]The date of the appearance of smallpox is not settled. It most likely evolved from a rodent virus between 68,000 and 16,000 years ago.[25][26] The wide range of dates is due to the different records used to calibrate the molecular clock. One clade was the variola major strains (the more clinically severe form of smallpox) which spread from Asia between 400 and 1,600 years ago. A second clade included both alastrim minor (a phenotypically mild smallpox) described from the American continents and isolates from West Africa which diverged from an ancestral strain between 1,400 and 6,300 years before present. This clade further diverged into two subclades at least 800 years ago.[citation needed]

A second estimate has placed the separation of variola from Taterapox at 3000–4000 years ago.[22] This is consistent with archaeological and historical evidence regarding the appearance of smallpox as a human disease which suggests a relatively recent origin. However, if the mutation rate is assumed to be similar to that of the herpesviruses the divergence date between variola from Taterapox has been estimated to be 50,000 years ago.[22] While this is consistent with the other published estimates it suggests that the archaeological and historical evidence is very incomplete. Better estimates of mutation rates in these viruses are needed.[citation needed]

Taxonomy

[edit]The species in the subfamily Chordopoxvirinae infect vertebrates and those in the subfamily Entomopoxvirinae infect insects.

The following subfamilies and genera are recognized (-virinae denotes subfamily and -virus denotes genus):[2]

Subfamily: Chordopoxvirinae

Subfamily: Entomopoxvirinae

Vaccinia virus

[edit]The prototypical poxvirus is vaccinia virus, known for its role in the eradication of smallpox. The vaccinia virus is an effective tool for foreign protein expression, as it elicits a strong host immune-response. The vaccinia virus enters cells primarily by cell fusion, although currently the receptor responsible is unknown.[citation needed]

Vaccinia contains three classes of genes: early, intermediate and late. These genes are transcribed by viral RNA polymerase and associated transcription factors. Vaccinia replicates its genome in the cytoplasm of infected cells, and after late-stage gene expression undergoes virion morphogenesis, which produces intracellular mature virions contained within an envelope membrane. The origin of the envelope membrane is still unknown. The intracellular mature virions are then transported to the Golgi apparatus where it is wrapped with an additional two membranes, becoming the intracellular enveloped virus. This is transported along cytoskeletal microtubules to reach the cell periphery, where it fuses with the plasma membrane to become the cell-associated enveloped virus. This triggers actin tails on cell surfaces or is released as external enveloped virion.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Viral Zone". ExPASy. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Virus Taxonomy: 2024 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "Pathogenic Molluscum Contagiosum Virus Sequenced". Antiviral Agents Bulletin: 196–7. August 1996. Retrieved 16 July 2006.

- ^ Hopkins, Donald R. (2002) [1983]. The greatest killer: smallpox in history, with a new introduction. University of Chicago Press. p. 15.

By special permission of the late President Anwar el Sadat, I was allowed to examine the front upper half of Ramses V's unwrapped mummy in the Cairo Museum in 1979. …Inspection of the mummy revealed a rash of elevated "pustules," each about two to four millimeters in diameter, …(An attempt to prove that this rash was caused by smallpox by electron-microscopic examination of tiny pieces of tissue that had fallen on the shroud was unsuccessful. I was not permitted to excise one of the postules.) …The appearance of the larger pustules and the apparent distribution of the rash are similar to smallpox rashes I have seen in more recent victims

- ^ Date of Ramses V's death derived from the Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Margaret Bunson (New York: Facts On File, 2002) ISBN 0816045631 p.337.

- ^ Henderson, D. A.; Inglesby, Thomas V.; Bartlett, John G.; Ascher, Michael S.; Eitzen, Edward; Jahrling, Peter B.; Hauer, Jerome; Layton, Marcelle; McDade, Joseph; Osterholm, Michael T.; O'Toole, Tara; Parker, Gerald; Perl, Trish; Russell, Philip K.; Tonat, Kevin; For The Working Group On Civilian Biodefense (1999). "Smallpox as a Biological Weapon: Medical and Public Health Management". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 281 (22): 2127–37. doi:10.1001/jama.281.22.2127. PMID 10367824.

- ^ Chan, Winnie M.; McFadden, Grant (1 September 2014). "Oncolytic Poxviruses". Annual Review of Virology. 1 (1): 119–141. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085442. ISSN 2327-056X. PMC 4380149. PMID 25839047.

- ^ Evgin, Laura; Vähä-Koskela, Markus; Rintoul, Julia; Falls, Theresa; Le Boeuf, Fabrice; Barrett, John W.; Bell, John C.; Stanford, Marianne M. (May 2010). "Potent oncolytic activity of raccoonpox virus in the absence of natural pathogenicity". Molecular Therapy. 18 (5): 896–902. doi:10.1038/mt.2010.14. ISSN 1525-0024. PMC 2890119. PMID 20160706.

- ^ Suryawanshi, Yogesh R.; Zhang, Tiantian; Razi, Farzad; Essani, Karim (July 2020). "Tanapoxvirus: From discovery towards oncolytic immunovirotherapy". Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 16 (4): 708–712. doi:10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_157_18. ISSN 1998-4138. PMID 32930107.

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (15 June 2004). "ICTVdb Descriptions: 58. Poxviridae". Archived from the original on 19 February 2001. Retrieved 26 February 2005.

- ^ How Big is a ... ? at Cells Alive!. Retrieved 2005-02-26.

- ^ Gubser, C; Hué, S; Kellam, P; Smith, GL (2004). "Poxvirus genomes: a phylogenetic analysis". J Gen Virol. 85 (1): 105–117. doi:10.1099/vir.0.19565-0. PMID 14718625.

- ^ Roychoudhury, S; Pan, A; Mukherjee, D (2011). "Genus specific evolution of codon usage and nucleotide compositional traits of poxviruses". Virus Genes. 42 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1007/s11262-010-0568-2. PMID 21369827. S2CID 21779605.

- ^ "Orthopoxvirus replication ~ ViralZone". viralzone.expasy.org. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ Mutsafi, Y; Zauberman, N; Sabanay, I; Minsky, A (30 March 2010). "Vaccinia-like cytoplasmic replication of the giant Mimivirus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 107 (13): 5978–82. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5978M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0912737107. PMC 2851855. PMID 20231474..

- ^ Racaniello, Vincent (4 March 2014). "Pithovirus: Bigger than Pandoravirus with a smaller genome". Virology Blog. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "DNA-dependent RNA polymerase rpo35 (Vaccinia virus)". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA.

- ^ Bahar, MW; Graham, SC; Stuart, DI; Grimes, JM (2011). "Insights into the evolution of a complex virus from the crystal structure of vaccinia virus D13". Structure. 19 (7): 1011–1020. doi:10.1016/j.str.2011.03.023. PMC 3136756. PMID 21742267.

- ^ Prangishvili, D; Garrett, RA (2004). "Exceptionally diverse morphotypes and genomes of crenarchaeal hyperthermophilic viruses" (PDF). Biochem Soc Trans (Submitted manuscript). 32 (2): 204–208. doi:10.1042/bst0320204. PMID 15046572. S2CID 20018642.

- ^ Babkin IV, Shchelkunov SN (2006) The time scale in poxvirus evolution. Mol Biol (Mosk) 40(1):20-24

- ^ a b Babkin, IV; Babkina, IN (2011). "Molecular dating in the evolution of vertebrate poxviruses". Intervirology. 54 (5): 253–260. doi:10.1159/000320964. PMID 21228539.

- ^ a b c Hughes, AL; Irausquin, S; Friedman, R (2010). "The evolutionary biology of poxviruses". Infect Genet Evol. 10 (1): 50–59. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.10.001. PMC 2818276. PMID 19833230.

- ^ Gjessing, MC; Yutin, N; Tengs, T; Senkevich, T; Koonin, E; Rønning, HP; Alarcon, M; Ylving, S; Lie, KI; Saure, B; Tran, L; Moss, B; Dale, OB (2015). "Salmon Gill Poxvirus, the Deepest Representative of the Chordopoxvirinae". J Virol. 89 (18): 9348–9867. doi:10.1128/JVI.01174-15. PMC 4542343. PMID 26136578.

- ^ Wibbelt, Gudrun; Tausch, Simon H.; Dabrowski, Piotr W.; Kershaw, Olivia; Nitsche, Andreas; Schrick, Livia (2017). "Berlin Squirrelpox Virus, a New Poxvirus in Red Squirrels, Berlin, Germany". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 23 (10): 1726–1729. doi:10.3201/eid2310.171008. PMC 5621524. PMID 28930029.(for systematic see figure 2)

- ^ Esposito, JJ; Sammons, SA; Frace, AM; Osborne, JD; Olsen-Rasmussen, M; Zhang, M; Govil, D; Damon, IK; et al. (August 2006). "Genome sequence diversity and clues to the evolution of variola (smallpox) virus". Science (Submitted manuscript). 313 (5788): 807–812. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..807E. doi:10.1126/science.1125134. PMID 16873609. S2CID 39823899.

- ^ Li, Y; Carroll, DS; Gardner, SN; Walsh, MC; Vitalis, EA; Damon, IK (2007). "On the origin of smallpox: correlating variola phylogenics with historical smallpox records". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104 (40): 15787–15792. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10415787L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609268104. PMC 2000395. PMID 17901212.

External links

[edit]- Electron micrographs of Orthopoxvirus and Parapoxvirus Genera, including the smallpox virus, have been collected by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses in their Poxviridae picture gallery.

- Buller, R. Mark L.; Palumbo, Gregory J. (1991). "Poxvirus Pathogenesis". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 55 (1): 80–122. doi:10.1128/mr.55.1.80-122.1991. PMC 372802. PMID 1851533.

- NCBI Taxonomy Page.

- Poxviridae at the Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center Archived 5 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- Viralzone: Poxviridae

- ICTV

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Poxviridae

Poxviridae

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Characteristics

Poxviridae constitutes a family of large, enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses distinguished by their cytoplasmic replication cycle, a trait atypical among DNA viruses which predominantly utilize the host nucleus.[2] Virions exhibit a complex architecture, featuring an external lipid envelope surrounding a core that encapsulates the genome along with lateral bodies containing enzymes essential for early transcription.[2] This family encompasses pathogens affecting vertebrates and insects, with genomes encoding up to 300 proteins that facilitate independent replication machinery, immune evasion, and host interaction.[9] Morphologically, poxvirus particles are brick-shaped or ovoid, measuring approximately 220–450 nm in length, 140–260 nm in width, and 140–260 nm in thickness, rendering them visible under light microscopy in some preparations.[1] The virions demonstrate ether resistance, preserving infectivity under lipid solvent exposure, and display extensive serological cross-reactivity across genera due to conserved structural proteins.[10] Internal structure includes a biconcave core with the linear dsDNA genome, covalently closed at termini via hairpin loops, spanning 128–375 kilobase pairs with inverted terminal repeats facilitating recombination and genome resolution.[9] Replication initiates post-entry via fusion or endocytosis, with uncoating releasing the core to transcribe early genes in the cytoplasm using packaged RNA polymerase, followed by DNA synthesis via viral polymerases and accessory factors, culminating in assembly at cytoplasmic factories and envelopment by Golgi-derived membranes.[2] This self-contained cytosolic lifecycle, encoding over 100 non-essential genes for host adaptation, underscores the family's evolutionary divergence from nuclear-replicating herpesviruses despite shared dsDNA nature.[4]Etymology

The name Poxviridae derives from the English word "pox", referring to the characteristic pustular skin lesions (pocks) produced by viruses in this family, combined with the taxonomic suffix "-viridae", which denotes a virus family.[1][11] The root "pox" traces to Old English poc or pocc, meaning "pustule", and evolved through Middle English pocke to describe blister-like eruptions associated with diseases such as smallpox.[1][12] This nomenclature reflects the family's historical association with vertebrate pox diseases featuring such lesions, as established in early virological classifications.[11]Taxonomy and Classification

Subfamilies and Genera

The family Poxviridae is divided into two subfamilies, Chordopoxvirinae and Entomopoxvirinae, primarily distinguished by host specificity, with Chordopoxvirinae infecting vertebrate chordates (including mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish) and Entomopoxvirinae infecting insects from four orders (Orthoptera, Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, and Diptera).[1] This classification reflects fundamental differences in viral-host interactions, genome organization, and virion morphology, as established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).[1] The subfamily Chordopoxvirinae encompasses 18 genera, reflecting a broad range of vertebrate hosts and associated diseases, such as smallpox in humans caused by Variola virus in the genus Orthopoxvirus. These genera include:- Avipoxvirus (avian hosts, e.g., fowlpox virus)

- Capripoxvirus (ruminants, e.g., sheeppox virus)

- Centapoxvirus

- Cervidpoxvirus (deer)

- Crocodylidpoxvirus (crocodilians)

- Leporipoxvirus (lagomorphs, e.g., myxoma virus)

- Macropopoxvirus (marsupials)

- Molluscipoxvirus (molluscum contagiosum virus in humans)

- Mustelpoxvirus (mustelids, e.g., skunkpox virus)

- Orthopoxvirus (mammals, including vaccinia and monkeypox viruses)

- Oryzopoxvirus (rodents)

- Parapoxvirus (e.g., orf virus in sheep)

- Pteropopoxvirus (bats)

- Salmonpoxvirus (salmonids)

- Sciuripoxvirus (squirrels)

- Suipoxvirus (swinepox virus)

- Vespertilionpoxvirus (bats)

- Yatapoxvirus (primates, e.g., tanapox virus)

- Alphaentomopoxvirus (primarily Coleoptera and Lepidoptera)

- Betaentomopoxvirus (Orthoptera and Coleoptera)

- Deltaentomopoxvirus (Nematocera)

- Gammaentomopoxvirus (Hymenoptera)