Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Virology

View on Wikipedia

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, their interaction with host organism physiology and immunity, the diseases they cause, the techniques to isolate and culture them, and their use in research and therapy.

The identification of the causative agent of tobacco mosaic disease (TMV) as a novel pathogen by Martinus Beijerinck (1898) is now acknowledged as being the official beginning of the field of virology as a discipline distinct from bacteriology. He realized the source was neither a bacterial nor a fungal infection, but something completely different. Beijerinck used the word "virus" to describe the mysterious agent in his 'contagium vivum fluidum' ('contagious living fluid'). Rosalind Franklin proposed the full structure of the tobacco mosaic virus in 1955.

One main motivation for the study of viruses is because they cause many infectious diseases of plants and animals.[1] The study of the manner in which viruses cause disease is viral pathogenesis. The degree to which a virus causes disease is its virulence.[2] These fields of study are called plant virology, animal virology and human or medical virology.[3]

Virology began when there were no methods for propagating or visualizing viruses or specific laboratory tests for viral infections. The methods for separating viral nucleic acids (RNA and DNA) and proteins, which are now the mainstay of virology, did not exist. Now there are many methods for observing the structure and functions of viruses and their component parts. Thousands of different viruses are now known about and virologists often specialize in either the viruses that infect plants, or bacteria and other microorganisms, or animals. Viruses that infect humans are now studied by medical virologists. Virology is a broad subject covering biology, health, animal welfare, agriculture and ecology.

History

[edit]

Louis Pasteur was unable to find a causative agent for rabies and speculated about a pathogen too small to be detected by microscopes.[4] In 1884, the French microbiologist Charles Chamberland invented the Chamberland filter (or Pasteur-Chamberland filter) with pores small enough to remove all bacteria from a solution passed through it.[5] In 1892, the Russian biologist Dmitri Ivanovsky used this filter to study what is now known as the tobacco mosaic virus: crushed leaf extracts from infected tobacco plants remained infectious even after filtration to remove bacteria. Ivanovsky suggested the infection might be caused by a toxin produced by bacteria, but he did not pursue the idea.[6] At the time it was thought that all infectious agents could be retained by filters and grown on a nutrient medium—this was part of the germ theory of disease.[7]

In 1898, the Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck repeated the experiments and became convinced that the filtered solution contained a new form of infectious agent.[8] He observed that the agent multiplied only in cells that were dividing, but as his experiments did not show that it was made of particles, he called it a contagium vivum fluidum (soluble living germ) and reintroduced the word virus. Beijerinck maintained that viruses were liquid in nature, a theory later discredited by Wendell Stanley, who proved they were particulate.[6] In the same year, Friedrich Loeffler and Paul Frosch passed the first animal virus, aphthovirus (the agent of foot-and-mouth disease), through a similar filter.[9]

In the early 20th century, the English bacteriologist Frederick Twort discovered a group of viruses that infect bacteria, now called bacteriophages (or commonly 'phages'), in 1915.[10][11] The French-Canadian microbiologist Félix d'Herelle announced his independent discovery of bacteriophages in 1917. D'Herelle described viruses that, when added to bacteria on an agar plate, would produce areas of dead bacteria. He accurately diluted a suspension of these viruses and discovered that the highest dilutions (lowest virus concentrations), rather than killing all the bacteria, formed discrete areas of dead organisms. Counting these areas and multiplying by the dilution factor allowed him to calculate the number of viruses in the original suspension.[12] Phages were heralded as a potential treatment for diseases such as typhoid and cholera, but their promise was forgotten with the development of penicillin. The development of bacterial resistance to antibiotics has renewed interest in the therapeutic use of bacteriophages.[13]

By the end of the 19th century, viruses were defined in terms of their infectivity, their ability to pass filters, and their requirement for living hosts. Viruses had been grown only in plants and animals. In 1906 Ross Granville Harrison invented a method for growing tissue in lymph, and in 1913 E. Steinhardt, C. Israeli, and R.A. Lambert used this method to grow vaccinia virus in fragments of guinea pig corneal tissue.[14] In 1928, H. B. Maitland and M. C. Maitland grew vaccinia virus in suspensions of minced hens' kidneys. Their method was not widely adopted until the 1950s when poliovirus was grown on a large scale for vaccine production.[15]

Another breakthrough came in 1931 when the American pathologist Ernest William Goodpasture and Alice Miles Woodruff grew influenza and several other viruses in fertilised chicken eggs.[16] In 1949, John Franklin Enders, Thomas Weller, and Frederick Robbins grew poliovirus in cultured cells from aborted human embryonic tissue,[17] the first virus to be grown without using solid animal tissue or eggs. This work enabled Hilary Koprowski, and then Jonas Salk, to make an effective polio vaccine.[18]

The first images of viruses were obtained upon the invention of electron microscopy in 1931 by the German engineers Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll.[19] In 1935, American biochemist and virologist Wendell Meredith Stanley examined the tobacco mosaic virus and found it was mostly made of protein.[20] A short time later, this virus was separated into protein and RNA parts.[21] The tobacco mosaic virus was the first to be crystallised and its structure could, therefore, be elucidated in detail. The first X-ray diffraction pictures of the crystallised virus were obtained by Bernal and Fankuchen in 1941. Based on her X-ray crystallographic pictures, Rosalind Franklin discovered the full structure of the virus in 1955.[22] In the same year, Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat and Robley Williams showed that purified tobacco mosaic virus RNA and its protein coat can assemble by themselves to form functional viruses, suggesting that this simple mechanism was probably the means through which viruses were created within their host cells.[23]

The second half of the 20th century was the golden age of virus discovery, and most of the documented species of animal, plant, and bacterial viruses were discovered during these years.[24] In 1946, bovine viral diarrhoea (a pestivirus) was first described. In 1957 equine arterivirus was discovered. In 1963 the hepatitis B virus was discovered by Baruch Blumberg.[25] In 1965 Howard Temin described the first retrovirus. Reverse transcriptase, the enzyme that retroviruses use to make DNA copies of their RNA, was first described in 1970 by Temin and David Baltimore independently.[26] In 1983 Luc Montagnier's team at the Pasteur Institute in France, first isolated the retrovirus now called HIV.[27] In 1989 Michael Houghton's team at Chiron Corporation discovered hepatitis C.[28][29]

Detecting viruses

[edit]

There are several approaches to detecting viruses and these include the detection of virus particles (virions) or their antigens or nucleic acids and infectivity assays.

Electron microscopy

[edit]

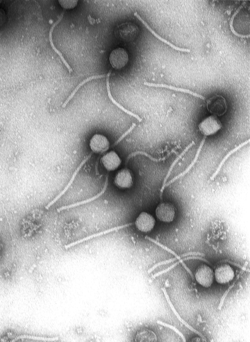

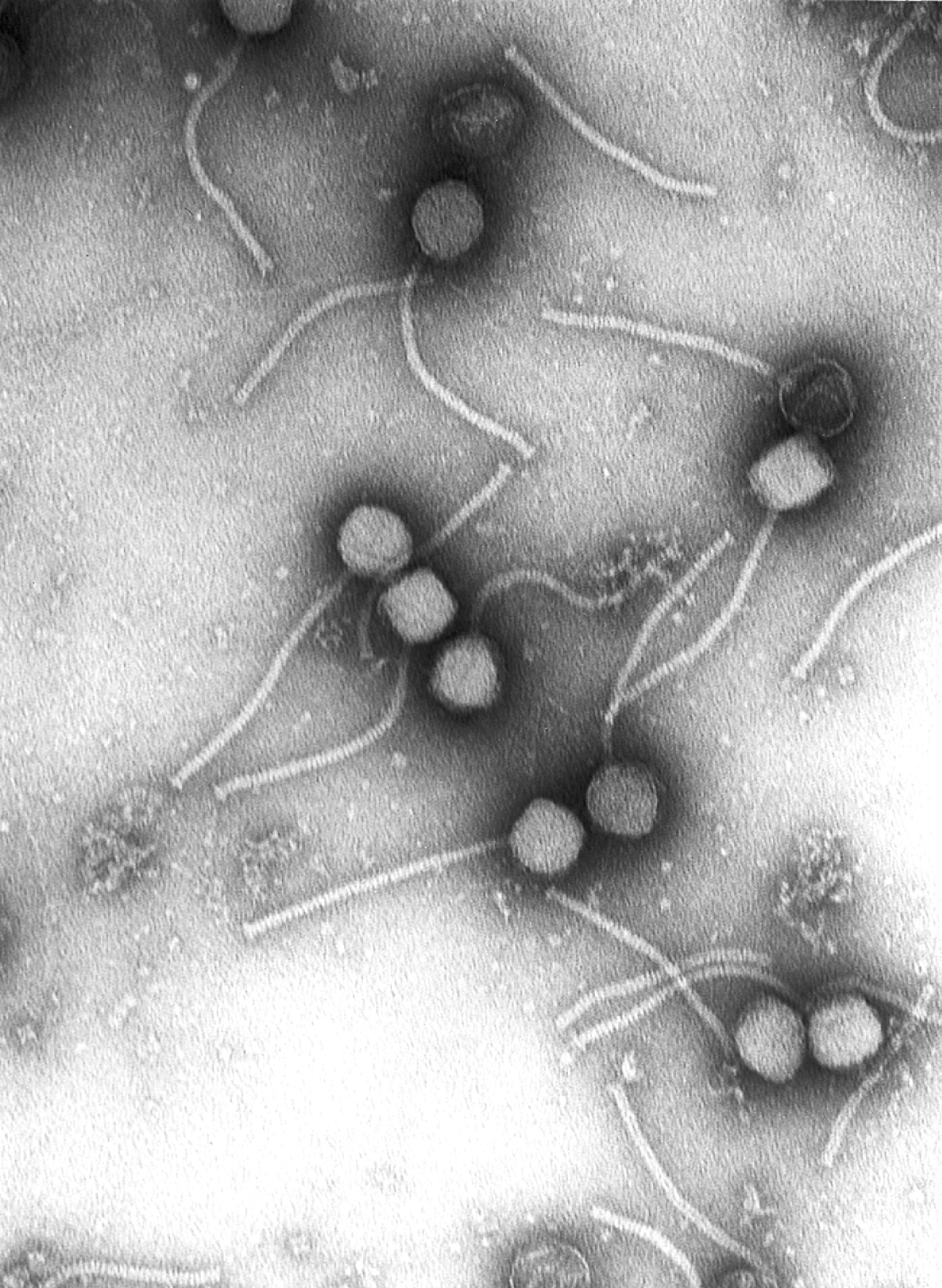

Viruses were seen for the first time in the 1930s when electron microscopes were invented. These microscopes use beams of electrons instead of light, which have a much shorter wavelength and can detect objects that cannot be seen using light microscopes. The highest magnification obtainable by electron microscopes is up to 10,000,000 times[30] whereas for light microscopes it is around 1,500 times.[31]

Virologists often use negative staining to help visualise viruses. In this procedure, the viruses are suspended in a solution of metal salts such as uranium acetate. The atoms of metal are opaque to electrons and the viruses are seen as suspended in a dark background of metal atoms.[30] This technique has been in use since the 1950s.[32] Many viruses were discovered using this technique and negative staining electron microscopy is still a valuable weapon in a virologist's arsenal.[33]

Traditional electron microscopy has disadvantages in that viruses are damaged by drying in the high vacuum inside the electron microscope and the electron beam itself is destructive.[30] In cryogenic electron microscopy the structure of viruses is preserved by embedding them in an environment of vitreous water.[34] This allows the determination of biomolecular structures at near-atomic resolution,[35] and has attracted wide attention to the approach as an alternative to X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy for the determination of the structure of viruses.[36]

Growth in cultures

[edit]Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites and because they only reproduce inside the living cells of a host these cells are needed to grow them in the laboratory. For viruses that infect animals (usually called "animal viruses") cells grown in laboratory cell cultures are used. In the past, fertile hens' eggs were used and the viruses were grown on the membranes surrounding the embryo. This method is still used in the manufacture of some vaccines. For the viruses that infect bacteria, the bacteriophages, the bacteria growing in test tubes can be used directly. For plant viruses, the natural host plants can be used or, particularly when the infection is not obvious, so-called indicator plants, which show signs of infection more clearly.[37][38]

Viruses that have grown in cell cultures can be indirectly detected by the detrimental effect they have on the host cell. These cytopathic effects are often characteristic of the type of virus. For instance, herpes simplex viruses produce a characteristic "ballooning" of the cells, typically human fibroblasts. Some viruses, such as mumps virus cause red blood cells from chickens to firmly attach to the infected cells. This is called "haemadsorption" or "hemadsorption". Some viruses produce localised "lesions" in cell layers called plaques, which are useful in quantitation assays and in identifying the species of virus by plaque reduction assays.[39][40]

Viruses growing in cell cultures are used to measure their susceptibility to validated and novel antiviral drugs.[41]

Serology

[edit]Viruses are antigens that induce the production of antibodies and these antibodies can be used in laboratories to study viruses. Related viruses often react with each other's antibodies and some viruses can be named based on the antibodies they react with. The use of the antibodies which were once exclusively derived from the serum (blood fluid) of animals is called serology.[42] Once an antibody–reaction has taken place in a test, other methods are needed to confirm this. Older methods included complement fixation tests,[43] hemagglutination inhibition and virus neutralisation.[44] Newer methods use enzyme immunoassays (EIA).[45]

In the years before PCR was invented immunofluorescence was used to quickly confirm viral infections. It is an infectivity assay that is virus species specific because antibodies are used. The antibodies are tagged with a dye that is luminescencent and when using an optical microscope with a modified light source, infected cells glow in the dark.[46]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other nucleic acid detection methods

[edit]PCR is a mainstay method for detecting viruses in all species including plants and animals. It works by detecting traces of virus specific RNA or DNA. It is very sensitive and specific, but can be easily compromised by contamination. Most of the tests used in veterinary virology and medical virology are based on PCR or similar methods such as transcription mediated amplification. When a novel virus emerges, such as the covid coronavirus, a specific test can be devised quickly so long as the viral genome has been sequenced and unique regions of the viral DNA or RNA identified.[47] The invention of microfluidic tests as allowed for most of these tests to be automated,[48] Despite its specificity and sensitivity, PCR has a disadvantage in that it does not differentiate infectious and non-infectious viruses and "tests of cure" have to be delayed for up to 21 days to allow for residual viral nucleic acid to clear from the site of the infection.[49]

Diagnostic tests

[edit]In laboratories many of the diagnostic test for detecting viruses are nucleic acid amplification methods such as PCR. Some tests detect the viruses or their components as these include electron microscopy and enzyme-immunoassays. The so-called "home" or "self"-testing gadgets are usually lateral flow tests, which detect the virus using a tagged monoclonal antibody.[50] These are also used in agriculture, food and environmental sciences.[51]

Quantitation and viral loads

[edit]Counting viruses (quantitation) has always had an important role in virology and has become central to the control of some infections of humans where the viral load is measured.[52] There are two basic methods: those that count the fully infective virus particles, which are called infectivity assays, and those that count all the particles including the defective ones.[30]

Infectivity assays

[edit]

Infectivity assays measure the amount (concentration) of infective viruses in a sample of known volume.[53] For host cells, plants or cultures of bacterial or animal cells are used. Laboratory animals such as mice have also been used particularly in veterinary virology.[54] These are assays are either quantitative where the results are on a continuous scale or quantal, where an event either occurs or it does not. Quantitative assays give absolute values and quantal assays give a statistical probability such as the volume of the test sample needed to ensure 50% of the hosts cells, plants or animals are infected. This is called the median infectious dose or ID 50.[55] Infective bacteriophages can be counted by seeding them onto "lawns" of bacteria in culture dishes. When at low concentrations, the viruses form holes in the lawn that can be counted. The number of viruses is then expressed as plaque forming units. For the bacteriophages that reproduce in bacteria that cannot be grown in cultures, viral load assays are used.[56]

The focus forming assay (FFA) is a variation of the plaque assay, but instead of relying on cell lysis in order to detect plaque formation, the FFA employs immunostaining techniques using fluorescently labeled antibodies specific for a viral antigen to detect infected host cells and infectious virus particles before an actual plaque is formed. The FFA is particularly useful for quantifying classes of viruses that do not lyse the cell membranes, as these viruses would not be amenable to the plaque assay. Like the plaque assay, host cell monolayers are infected with various dilutions of the virus sample and allowed to incubate for a relatively brief incubation period (e.g., 24–72 hours) under a semisolid overlay medium that restricts the spread of infectious virus, creating localized clusters (foci) of infected cells. Plates are subsequently probed with fluorescently labeled antibodies against a viral antigen, and fluorescence microscopy is used to count and quantify the number of foci. The FFA method typically yields results in less time than plaque or fifty-percent-tissue-culture-infective-dose (TCID50) assays, but it can be more expensive in terms of required reagents and equipment. Assay completion time is also dependent on the size of area that the user is counting. A larger area will require more time but can provide a more accurate representation of the sample. Results of the FFA are expressed as focus forming units per milliliter, or FFU/mL.[57]

Viral load assays

[edit]When an assay for measuring the infective virus particle is done (Plaque assay, Focus assay), viral titre often refers to the concentration of infectious viral particles, which is different from the total viral particles. Viral load assays usually count the number of viral genomes present rather than the number of particles and use methods similar to PCR.[58] Viral load tests are an important in the control of infections by HIV.[59] This versatile method can be used for plant viruses.[60][61]

Molecular biology

[edit]Molecular virology is the study of viruses at the level of nucleic acids and proteins. The methods invented by molecular biologists have all proven useful in virology. Their small sizes and relatively simple structures make viruses an ideal candidate for study by these techniques.

Purifying viruses and their components

[edit]

For further study, viruses grown in the laboratory need purifying to remove contaminants from the host cells. The methods used often have the advantage of concentrating the viruses, which makes it easier to investigate them.

Centrifugation

[edit]Centrifuges are often used to purify viruses. Low speed centrifuges, i.e. those with a top speed of 10,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) are not powerful enough to concentrate viruses, but ultracentrifuges with a top speed of around 100,000 rpm, are and this difference is used in a method called differential centrifugation. In this method the larger and heavier contaminants are removed from a virus mixture by low speed centrifugation. The viruses, which are small and light and are left in suspension, are then concentrated by high speed centrifugation.[63]

Following differential centrifugation, virus suspensions often remain contaminated with debris that has the same sedimentation coefficient and are not removed by the procedure. In these cases a modification of centrifugation, called buoyant density centrifugation, is used. In this method the viruses recovered from differential centrifugation are centrifuged again at very high speed for several hours in dense solutions of sugars or salts that form a density gradient, from low to high, in the tube during the centrifugation. In some cases, preformed gradients are used where solutions of steadily decreasing density are carefully overlaid on each other. Like an object in the Dead Sea, despite the centrifugal force the virus particles cannot sink into solutions that are more dense than they are and they form discrete layers of, often visible, concentrated viruses in the tube. Caesium chloride is often used for these solutions as it is relatively inert but easily self-forms a gradient when centrifuged at high speed in an ultracentrifuge.[62] Buoyant density centrifugation can also be used to purify the components of viruses such as their nucleic acids or proteins.[64]

Electrophoresis

[edit]

The separation of molecules based on their electric charge is called electrophoresis. Viruses and all their components can be separated and purified using this method. This is usually done in a supporting medium such as agarose and polyacrylamide gels. The separated molecules are revealed using stains such as coomasie blue, for proteins, or ethidium bromide for nucleic acids. In some instances the viral components are rendered radioactive before electrophoresis and are revealed using photographic film in a process known as autoradiography.[65]

Sequencing of viral genomes

[edit]As most viruses are too small to be seen by a light microscope, sequencing is one of the main tools in virology to identify and study the virus. Traditional Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are used to sequence viruses in basic and clinical research, as well as for the diagnosis of emerging viral infections, molecular epidemiology of viral pathogens, and drug-resistance testing. There are more than 2.3 million unique viral sequences in GenBank.[66] NGS has surpassed traditional Sanger as the most popular approach for generating viral genomes.[66] Viral genome sequencing as become a central method in viral epidemiology and viral classification.

Phylogenetic analysis

[edit]Data from the sequencing of viral genomes can be used to determine evolutionary relationships and this is called phylogenetic analysis.[67] Software, such as PHYLIP, is used to draw phylogenetic trees. This analysis is also used in studying the spread of viral infections in communities (epidemiology).[68]

Cloning

[edit]When purified viruses or viral components are needed for diagnostic tests or vaccines, cloning can be used instead of growing the viruses.[69] At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic the availability of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA sequence enabled tests to be manufactured quickly.[70] There are several proven methods for cloning viruses and their components. Small pieces of DNA called cloning vectors are often used and the most common ones are laboratory modified plasmids (small circular molecules of DNA produced by bacteria). The viral nucleic acid, or a part of it, is inserted in the plasmid, which is the copied many times over by bacteria. This recombinant DNA can then be used to produce viral components without the need for native viruses.[71]

Phage virology

[edit]The viruses that reproduce in bacteria, archaea and fungi are informally called "phages",[72] and the ones that infect bacteria – bacteriophages – in particular are useful in virology and biology in general.[73] Bacteriophages were some of the first viruses to be discovered, early in the twentieth century,[74] and because they are relatively easy to grow quickly in laboratories, much of our understanding of viruses originated by studying them.[74] Bacteriophages, long known for their positive effects in the environment, are used in phage display techniques for screening proteins DNA sequences. They are a powerful tool in molecular biology.[75]

Genetics

[edit]All viruses have genes which are studied using genetics.[76] All the techniques used in molecular biology, such as cloning, creating mutations RNA silencing are used in viral genetics.[77]

Reassortment

[edit]Reassortment is the switching of genes from different parents and it is particularly useful when studying the genetics of viruses that have segmented genomes (fragmented into two or more nucleic acid molecules) such as influenza viruses and rotaviruses. The genes that encode properties such as serotype can be identified in this way.[78]

Recombination

[edit]Often confused with reassortment, recombination is also the mixing of genes but the mechanism differs in that stretches of DNA or RNA molecules, as opposed to the full molecules, are joined during the RNA or DNA replication cycle. Recombination is not as common as reassortment in nature but it is a powerful tool in laboratories for studying the structure and functions of viral genes.[79]

Reverse genetics

[edit]Reverse genetics is a powerful research method in virology.[80] In this procedure complementary DNA (cDNA) copies of virus genomes called "infectious clones" are used to produce genetically modified viruses that can be then tested for changes in say, virulence or transmissibility.[81]

Virus classification

[edit]A major branch of virology is virus classification. It is artificial in that it is not based on evolutionary phylogenetics but it is based shared or distinguishing properties of viruses.[82][83] It seeks to describe the diversity of viruses by naming and grouping them on the basis of similarities.[84] In 1962, André Lwoff, Robert Horne, and Paul Tournier were the first to develop a means of virus classification, based on the Linnaean hierarchical system.[85] This system based classification on phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. Viruses were grouped according to their shared properties (not those of their hosts) and the type of nucleic acid forming their genomes.[86] In 1966, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) was formed. The system proposed by Lwoff, Horne and Tournier was initially not accepted by the ICTV because the small genome size of viruses and their high rate of mutation made it difficult to determine their ancestry beyond order. As such, the Baltimore classification system has come to be used to supplement the more traditional hierarchy.[87] Starting in 2018, the ICTV began to acknowledge deeper evolutionary relationships between viruses that have been discovered over time and adopted a 15-rank classification system ranging from realm to species.[88] Additionally, some species within the same genus are grouped into a genogroup.[89][90]

ICTV classification

[edit]The ICTV developed the current classification system and wrote guidelines that put a greater weight on certain virus properties to maintain family uniformity. A unified taxonomy (a universal system for classifying viruses) has been established. Only a small part of the total diversity of viruses has been studied.[91] As of 2021, 6 realms, 10 kingdoms, 17 phyla, 2 subphyla, 39 classes, 65 orders, 8 suborders, 233 families, 168 subfamilies, 2,606 genera, 84 subgenera, and 10,434 species of viruses have been defined by the ICTV.[92]

The general taxonomic structure of taxon ranges and the suffixes used in taxonomic names are shown hereafter. As of 2021, the ranks of subrealm, subkingdom, and subclass are unused, whereas all other ranks are in use.[92]

- Realm (-viria)

Baltimore classification

[edit]

The Nobel Prize-winning biologist David Baltimore devised the Baltimore classification system.[93]

The Baltimore classification of viruses is based on the mechanism of mRNA production. Viruses must generate mRNAs from their genomes to produce proteins and replicate themselves, but different mechanisms are used to achieve this in each virus family. Viral genomes may be single-stranded (ss) or double-stranded (ds), RNA or DNA, and may or may not use reverse transcriptase (RT). In addition, ssRNA viruses may be either sense (+) or antisense (−). This classification places viruses into seven groups:

- I: dsDNA viruses (e.g. Adenoviruses, Herpesviruses, Poxviruses)

- II: ssDNA viruses (+ strand or "sense") DNA (e.g. Parvoviruses)

- III: dsRNA viruses (e.g. Reoviruses)

- IV:(+)ssRNA viruses (+ strand or sense) RNA (e.g. Coronaviruses, Picornaviruses, Togaviruses)

- V: (−)ssRNA viruses (− strand or antisense) RNA (e.g. Orthomyxoviruses, Rhabdoviruses)

- VI: ssRNA-RT viruses (+ strand or sense) RNA with DNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Retroviruses)

- VII: dsDNA-RT viruses DNA with RNA intermediate in life-cycle (e.g. Hepadnaviruses)

References

[edit]- ^ Dolja VV, Koonin EV (November 2011). "Common origins and host-dependent diversity of plant and animal viromes". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (5): 322–31. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.09.007. PMC 3293486. PMID 22408703.

- ^ Novella IS, Presloid JB, Taylor RT (December 2014). "RNA replication errors and the evolution of virus pathogenicity and virulence". Current Opinion in Virology. 9: 143–7. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2014.09.017. PMID 25462446.

- ^ Sales RK, Oraño J, Estanislao RD, Ballesteros AJ, Gomez MI (2021-04-29). "Research priority-setting for human, plant, and animal virology: an online experience for the Virology Institute of the Philippines". Health Research Policy and Systems. 19 (1): 70. doi:10.1186/s12961-021-00723-z. ISSN 1478-4505. PMC 8082216. PMID 33926472.

- ^ Bordenave G (May 2003). "Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)". Microbes and Infection. 5 (6): 553–60. doi:10.1016/S1286-4579(03)00075-3. PMID 12758285.

- ^ Shors pp. 74, 827

- ^ a b Collier p. 3

- ^ Dimmock p. 4

- ^ Dimmock pp. 4–5

- ^ Fenner F (2009). Mahy BW, Van Regenmortal MH (eds.). Desk Encyclopedia of General Virology (1 ed.). Oxford: Academic Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-12-375146-1.

- ^ Shors p. 827

- ^ Keen EC (2012). "Phage Therapy: Concept to Cure". Frontiers in Microbiology. 3: 238. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00238. PMC 3400130. PMID 22833738.

- ^ D'Herelle F (September 2007). "On an invisible microbe antagonistic toward dysenteric bacilli: brief note by Mr. F. D'Herelle, presented by Mr. Roux. 1917". Research in Microbiology. 158 (7): 553–54. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2007.07.005. PMID 17855060.

- ^ Domingo-Calap P, Georgel P, Bahram S (March 2016). "Back to the future: bacteriophages as promising therapeutic tools". HLA. 87 (3): 133–40. doi:10.1111/tan.12742. PMID 26891965. S2CID 29223662.

- ^ Steinhardt E, Israeli C, Lambert RA (1913). "Studies on the cultivation of the virus of vaccinia". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 13 (2): 294–300. doi:10.1093/infdis/13.2.294.

- ^ Collier p. 4

- ^ Goodpasture EW, Woodruff AM, Buddingh GJ (October 1931). "The cultivation of vaccine and other viruses in the chorioallantoic membrane of chick embryos". Science. 74 (1919): 371–72. Bibcode:1931Sci....74..371G. doi:10.1126/science.74.1919.371. PMID 17810781.

- ^ Thomas Huckle Weller (2004). Growing Pathogens in Tissue Cultures: Fifty Years in Academic Tropical Medicine, Pediatrics, and Virology. Boston Medical Library. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-88135-380-8.

- ^ Rosen FS (October 2004). "Isolation of poliovirus--John Enders and the Nobel Prize". The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (15): 1481–83. doi:10.1056/NEJMp048202. PMID 15470207.

- ^ Frängsmyr T, Ekspång G, eds. (1993). Nobel Lectures, Physics 1981–1990. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Bibcode:1993nlp..book.....F.

- In 1887, Buist visualised one of the largest, Vaccinia virus, by optical microscopy after staining it. Vaccinia was not known to be a virus at that time. (Buist J.B. Vaccinia and Variola: a study of their life history Churchill, London)

- ^ Stanley WM, Loring HS (January 1936). "The Isolation of Crystalline Tobacco Mosaic Virus Protein From Diseased Tomato Plants". Science. 83 (2143): 85. Bibcode:1936Sci....83...85S. doi:10.1126/science.83.2143.85. PMID 17756690.

- ^ Stanley WM, Lauffer MA (April 1939). "Disintegration of Tobacco Mosaic Virus in Urea Solutions". Science. 89 (2311): 345–47. Bibcode:1939Sci....89..345S. doi:10.1126/science.89.2311.345. PMID 17788438.

- ^ Creager AN, Morgan GJ (June 2008). "After the double helix: Rosalind Franklin's research on Tobacco mosaic virus". Isis. 99 (2): 239–72. doi:10.1086/588626. PMID 18702397. S2CID 25741967.

- ^ Dimmock p. 12

- ^ Norrby E (2008). "Nobel Prizes and the emerging virus concept". Archives of Virology. 153 (6): 1109–23. doi:10.1007/s00705-008-0088-8. PMID 18446425. S2CID 10595263.

- ^ Collier p. 745

- ^ Temin HM, Baltimore D (1972). "RNA-directed DNA synthesis and RNA tumor viruses". Advances in Virus Research. 17: 129–86. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60749-6. ISBN 9780120398171. PMID 4348509.

- ^ Barré-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, et al. (May 1983). "Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)". Science. 220 (4599): 868–71. Bibcode:1983Sci...220..868B. doi:10.1126/science.6189183. PMID 6189183.

- ^ Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M (April 1989). "Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome". Science. 244 (4902): 359–62. Bibcode:1989Sci...244..359C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.469.3592. doi:10.1126/science.2523562. PMID 2523562.

- ^ Houghton M (November 2009). "The long and winding road leading to the identification of the hepatitis C virus". Journal of Hepatology. 51 (5): 939–48. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2009.08.004. PMID 19781804.

- ^ a b c d Payne S (2017). "Methods to Study Viruses". Viruses. pp. 37–52. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00004-0. ISBN 978-0-12-803109-4.

- ^ "Magnification - Microscopy, size and magnification (CCEA) - GCSE Biology (Single Science) Revision - CCEA". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Brenner S, Horne RW (July 1959). "A negative staining method for high resolution electron microscopy of viruses". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 34: 103–10. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(59)90237-9. PMID 13804200.

- ^ Goldsmith CS, Miller SE (October 2009). "Modern uses of electron microscopy for detection of viruses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (4): 552–63. doi:10.1128/CMR.00027-09. PMC 2772359. PMID 19822888.

- ^ Tivol WF, Briegel A, Jensen GJ (October 2008). "An Improved Cryogen for Plunge Freezing". Microscopy and Microanalysis. 14 (5): 375–379. Bibcode:2008MiMic..14..375T. doi:10.1017/S1431927608080781. ISSN 1431-9276. PMC 3058946. PMID 18793481.

- ^ Cheng Y, Grigorieff N, Penczek PA, Walz T (April 2015). "A primer to single-particle cryo-electron microscopy". Cell. 161 (3): 438–449. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.050. PMC 4409659. PMID 25910204.

- ^ Stoddart C (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Liu JZ, Richerson K, Nelson RS (August 2009). "Growth Conditions for Plant Virus–Host Studies". Current Protocols in Microbiology. 14: Unit16A.1. doi:10.1002/9780471729259.mc16a01s14. PMID 19653216. S2CID 41236532.

- ^ Valmonte-Cortes GR, Lilly ST, Pearson MN, Higgins CM, MacDiarmid RM (January 2022). "The Potential of Molecular Indicators of Plant Virus Infection: Are Plants Able to Tell Us They Are Infected?". Plants. 11 (2): 188. Bibcode:2022Plnts..11..188V. doi:10.3390/plants11020188. PMC 8777591. PMID 35050076.

- ^ Gauger PC, Vincent AL (2014). "Serum Virus Neutralization Assay for Detection and Quantitation of Serum-Neutralizing Antibodies to Influenza a Virus in Swine". Animal Influenza Virus. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1161. pp. 313–24. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0758-8_26. ISBN 978-1-4939-0757-1. PMID 24899440.

- ^ Dimitrova K, Mendoza EJ, Mueller N, Wood H (2020). "A Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test for the Detection of ZIKV-Specific Antibodies". Zika Virus. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 2142. pp. 59–71. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0581-3_5. ISBN 978-1-0716-0580-6. PMID 32367358. S2CID 218504421.

- ^ Lampejo T (July 2020). "Influenza and antiviral resistance: an overview". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 39 (7): 1201–1208. doi:10.1007/s10096-020-03840-9. PMC 7223162. PMID 32056049.

- ^ Zainol Rashid Z, Othman SN, Abdul Samat MN, Ali UK, Wong KK (April 2020). "Diagnostic performance of COVID-19 serology assays". The Malaysian Journal of Pathology. 42 (1): 13–21. PMID 32342927.

- ^ Swack NS, Gahan TF, Hausler WJ (August 1992). "The present status of the complement fixation test in viral serodiagnosis". Infectious Agents and Disease. 1 (4): 219–24. PMID 1365549.

- ^ Smith TJ (August 2011). "Structural studies on antibody recognition and neutralization of viruses". Current Opinion in Virology. 1 (2): 150–6. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.020. PMC 3163491. PMID 21887208.

- ^ Mahony JB, Petrich A, Smieja M (2011). "Molecular diagnosis of respiratory virus infections". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 48 (5–6): 217–49. doi:10.3109/10408363.2011.640976. PMID 22185616. S2CID 24960083.

- ^ AbuSalah MA, Gan SH, Al-Hatamleh MA, Irekeola AA, Shueb RH, Yean Yean C (March 2020). "Recent Advances in Diagnostic Approaches for Epstein-Barr Virus". Pathogens. 9 (3): 226. doi:10.3390/pathogens9030226. PMC 7157745. PMID 32197545.

- ^ Zhu H, Zhang H, Xu Y, Laššáková S, Korabečná M, Neužil P (October 2020). "PCR past, present and future". BioTechniques. 69 (4): 317–325. doi:10.2144/btn-2020-0057. PMC 7439763. PMID 32815744.

- ^ Wang X, Hong XZ, Li YW, Li Y, Wang J, Chen P, Liu BF (March 2022). "Microfluidics-based strategies for molecular diagnostics of infectious diseases". Military Medical Research. 9 (1) 11. doi:10.1186/s40779-022-00374-3. PMC 8930194. PMID 35300739.

- ^ Benzigar MR, Bhattacharjee R, Baharfar M, Liu G (April 2021). "Current methods for diagnosis of human coronaviruses: pros and cons". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 413 (9): 2311–2330. doi:10.1007/s00216-020-03046-0. PMC 7679240. PMID 33219449.

- ^ Burrell CJ, Howard CR, Murphy FA (2017-01-01), Burrell CJ, Howard CR, Murphy FA (eds.), "Chapter 10 - Laboratory Diagnosis of Virus Diseases", Fenner and White's Medical Virology (Fifth Edition), London: Academic Press, pp. 135–154, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-375156-0.00010-2, ISBN 978-0-12-375156-0, PMC 7149825

- ^ Koczula KM, Gallotta A (June 2016). "Lateral flow assays". Essays in Biochemistry. 60 (1): 111–20. doi:10.1042/EBC20150012. PMC 4986465. PMID 27365041.

- ^ Lee MJ (October 2021). "Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 viral load: current status and future prospects". Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics. 21 (10): 1017–1023. doi:10.1080/14737159.2021.1962709. PMC 8425446. PMID 34369836.

- ^ Mistry BA, D'Orsogna MR, Chou T (June 2018). "The Effects of Statistical Multiplicity of Infection on Virus Quantification and Infectivity Assays". Biophysical Journal. 114 (12): 2974–2985. arXiv:1805.02810. Bibcode:2018BpJ...114.2974M. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2018.05.005. PMC 6026352. PMID 29925033.

- ^ Kashuba C, Hsu C, Krogstad A, Franklin C (January 2005). "Small mammal virology". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice. 8 (1): 107–22. doi:10.1016/j.cvex.2004.09.004. PMC 7110861. PMID 15585191.

- ^ Cutler TD, Wang C, Hoff SJ, Kittawornrat A, Zimmerman JJ (August 2011). "Median infectious dose (ID50) of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolate MN-184 via aerosol exposure". Veterinary Microbiology. 151 (3–4): 229–37. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.03.003. PMID 21474258.

- ^ Moon K, Cho JC (March 2021). "Metaviromics coupled with phage-host identification to open the viral "black box"". Journal of Microbiology (Seoul, Korea). 59 (3): 311–323. doi:10.1007/s12275-021-1016-9. PMID 33624268. S2CID 232023531.

- ^ Salgado EN, Upadhyayula S, Harrison SC (September 2017). "Single-Particle Detection of Transcription following Rotavirus Entry". Journal of Virology. 91 (18) e00651-17. doi:10.1128/JVI.00651-17. PMC 5571246. PMID 28701394.

- ^ Yokota I, Hattori T, Shane PY, Konno S, Nagasaka A, Takeyabu K, Fujisawa S, Nishida M, Teshima T (February 2021). "Equivalent SARS-CoV-2 viral loads by PCR between nasopharyngeal swab and saliva in symptomatic patients". Scientific Reports. 11 (1) 4500. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.4500Y. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-84059-2. PMC 7904914. PMID 33627730.

- ^ Nichols BE, Girdwood SJ, Crompton T, Stewart-Isherwood L, Berrie L, Chimhamhiwa D, Moyo C, Kuehnle J, Stevens W, Rosen S (September 2019). "Monitoring viral load for the last mile: what will it cost?". Journal of the International AIDS Society. 22 (9) e25337. doi:10.1002/jia2.25337. PMC 6742838. PMID 31515967.

- ^ Shirima RR, Maeda DG, Kanju E, Ceasar G, Tibazarwa FI, Legg JP (July 2017). "Absolute quantification of cassava brown streak virus mRNA by real-time qPCR". Journal of Virological Methods. 245: 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2017.03.003. PMC 5429390. PMID 28315718.

- ^ Rubio L, Galipienso L, Ferriol I (2020). "Detection of Plant Viruses and Disease Management: Relevance of Genetic Diversity and Evolution". Frontiers in Plant Science. 11 1092. Bibcode:2020FrPS...11.1092R. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.01092. PMC 7380168. PMID 32765569.

- ^ a b Beards GM (August 1982). "A method for the purification of rotaviruses and adenoviruses from faeces". Journal of Virological Methods. 4 (6): 343–52. doi:10.1016/0166-0934(82)90059-3. PMID 6290520.

- ^ Zhou Y, McNamara RP, Dittmer DP (August 2020). "Purification Methods and the Presence of RNA in Virus Particles and Extracellular Vesicles". Viruses. 12 (9): 917. doi:10.3390/v12090917. PMC 7552034. PMID 32825599.

- ^ Su Q, Sena-Esteves M, Gao G (May 2019). "Purification of the Recombinant Adenovirus by Cesium Chloride Gradient Centrifugation". Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2019 (5) pdb.prot095547. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot095547. PMID 31043560. S2CID 143423942.

- ^ Klepárník K, Boček P (March 2010). "Electrophoresis today and tomorrow: Helping biologists' dreams come true". BioEssays. 32 (3): 218–226. doi:10.1002/bies.200900152. PMID 20127703. S2CID 41587013.

- ^ a b Castro C, Marine R, Ramos E, Ng TF (22 June 2020). "The effect of variant interference on de novo assembly for viral deep sequencing". BMC Genomics. 21 (1): 421. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-06801-w. PMC 7306937. PMID 32571214.

- ^ Cui J, Li F, Shi ZL (March 2019). "Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 17 (3): 181–192. doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. PMC 7097006. PMID 30531947.

- ^ Gorbalenya AE, Lauber C (2017). "Phylogeny of Viruses ☆". Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.95723-4. ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3. PMC 7157450.

- ^ Koch L (July 2020). "A platform for RNA virus cloning". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 21 (7): 388. doi:10.1038/s41576-020-0246-8. PMC 7220607. PMID 32404960.

- ^ Thi Nhu Thao T, Labroussaa F, Ebert N, V'kovski P, Stalder H, Portmann J, Kelly J, Steiner S, Holwerda M, Kratzel A, Gultom M, Schmied K, Laloli L, Hüsser L, Wider M, Pfaender S, Hirt D, Cippà V, Crespo-Pomar S, Schröder S, Muth D, Niemeyer D, Corman VM, Müller MA, Drosten C, Dijkman R, Jores J, Thiel V (June 2020). "Rapid reconstruction of SARS-CoV-2 using a synthetic genomics platform". Nature. 582 (7813): 561–565. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..561T. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2294-9. PMID 32365353. S2CID 213516085.

- ^ Rosano GL, Morales ES, Ceccarelli EA (August 2019). "New tools for recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli: A 5-year update". Protein Science. 28 (8): 1412–1422. doi:10.1002/pro.3668. PMC 6635841. PMID 31219641.

- ^ Pennazio S (2006). "The origin of phage virology". Rivista di Biologia. 99 (1): 103–29. PMID 16791793.

- ^ Harada LK, Silva EC, Campos WF, Del Fiol FS, Vila M, Dąbrowska K, Krylov VN, Balcão VM (2018). "Biotechnological applications of bacteriophages: State of the art". Microbiological Research. 212–213: 38–58. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2018.04.007. hdl:1822/54758. PMID 29853167. S2CID 46921731.

- ^ a b Stone E, Campbell K, Grant I, McAuliffe O (June 2019). "Understanding and Exploiting Phage-Host Interactions". Viruses. 11 (6): 567. doi:10.3390/v11060567. PMC 6630733. PMID 31216787.

- ^ Nagano K, Tsutsumi Y (January 2021). "Phage Display Technology as a Powerful Platform for Antibody Drug Discovery". Viruses. 13 (2): 178. doi:10.3390/v13020178. PMC 7912188. PMID 33504115.

- ^ Ibrahim B, McMahon DP, Hufsky F, Beer M, Deng L, Mercier PL, Palmarini M, Thiel V, Marz M (June 2018). "A new era of virus bioinformatics". Virus Research. 251: 86–90. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2018.05.009. PMID 29751021. S2CID 21736957.

- ^ Bamford D, Zuckerman MA (2021). Encyclopedia of virology. Amsterdam: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-814516-6. OCLC 1240584737.

- ^ McDonald SM, Nelson MI, Turner PE, Patton JT (July 2016). "Reassortment in segmented RNA viruses: mechanisms and outcomes". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 14 (7): 448–60. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.46. PMC 5119462. PMID 27211789.

- ^ Li J, Arévalo MT, Zeng M (2013). "Engineering influenza viral vectors". Bioengineered. 4 (1): 9–14. doi:10.4161/bioe.21950. PMC 3566024. PMID 22922205.

- ^ Lee CW (2014). "Reverse Genetics of Influenza Virus". Animal Influenza Virus. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 1161. pp. 37–50. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-0758-8_4. ISBN 978-1-4939-0757-1. PMID 24899418.

- ^ Li Z, Zhong L, He J, Huang Y, Zhao Y (April 2021). "Development and application of reverse genetic technology for the influenza virus". Virus Genes. 57 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1007/s11262-020-01822-9. PMC 7851324. PMID 33528730.

- ^ Hull R, Rima B (November 2020). "Virus taxonomy and classification: naming of virus species". Archives of Virology. 165 (11): 2733–2736. doi:10.1007/s00705-020-04748-7. PMID 32740831. S2CID 220907379.

- ^ Pellett PE, Mitra S, Holland TC (2014). "Basics of virology". Neurovirology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 123. pp. 45–66. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53488-0.00002-X. ISBN 9780444534880. PMC 7152233. PMID 25015480.

- ^ Simmonds P, Aiewsakun P (August 2018). "Virus classification - where do you draw the line?". Archives of Virology. 163 (8): 2037–2046. doi:10.1007/s00705-018-3938-z. PMC 6096723. PMID 30039318.

- ^ Lwoff A, Horne RW, Tournier P (June 1962). "[A virus system]". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). 254: 4225–27. PMID 14467544.

- ^ Lwoff A, Horne R, Tournier P (1962). "A system of viruses". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 27: 51–55. doi:10.1101/sqb.1962.027.001.008. PMID 13931895.

- ^ Fauquet CM, Fargette D (August 2005). "International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses and the 3,142 unassigned species". Virology Journal. 2 64. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-2-64. PMC 1208960. PMID 16105179.

- ^ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses Executive Committee (May 2020). "The New Scope of Virus Taxonomy: Partitioning the Virosphere Into 15 Hierarchical Ranks". Nat Microbiol. 5 (5): 668–674. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0709-x. PMC 7186216. PMID 32341570.

- ^ Khan MK, Alam MM (July 2021). "Norovirus Gastroenteritis Outbreaks, Genomic Diversity and Evolution: An Overview". Mymensingh Medical Journal. 30 (3): 863–873. PMID 34226482.

- ^ Eberle J, Gürtler L (2012). "HIV types, groups, subtypes and recombinant forms: errors in replication, selection pressure and quasispecies". Intervirology. 55 (2): 79–83. doi:10.1159/000331993. PMID 22286874. S2CID 5642060.

- ^ Delwart EL (2007). "Viral metagenomics". Reviews in Medical Virology. 17 (2): 115–31. doi:10.1002/rmv.532. PMC 7169062. PMID 17295196.

- ^ a b "Virus Taxonomy: 2021 Release". talk.ictvonline.org. International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Koonin EV, Krupovic M, Agol VI (August 2021). "The Baltimore Classification of Viruses 50 Years Later: How Does It Stand in the Light of Virus Evolution?" (PDF). Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 85 (3) e0005321. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00053-21. PMC 8483701. PMID 34259570. S2CID 235821748.

Bibliography

[edit]- Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M (1998). Mahy B, Collier LA (eds.). Topley and Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections. Virology. Vol. 1 (Ninth ed.). ISBN 0-340-66316-2.

- Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ, Leppard K (2007). Introduction to Modern Virology (Sixth ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3645-7.

- Shors T (2017). Understanding Viruses. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-1-284-02592-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Virology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Virology at Wikimedia Commons- Official website of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses

Virology

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

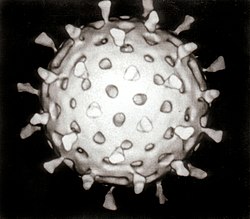

Viruses are defined as obligate intracellular parasites that depend entirely on the cellular machinery of host organisms for their replication and propagation.[3] Unlike bacteria or other microbes, viruses cannot reproduce independently and must infect a living host cell to hijack its metabolic processes and biosynthetic pathways.[5] This parasitic lifestyle distinguishes viruses as non-autonomous entities that exist extracellularly as inert particles until they encounter a suitable host.[6] Viruses are acellular, lacking the organelles, cytoplasm, and metabolic capabilities found in cellular life forms, including ribosomes for protein synthesis and independent energy production.[7] They typically range in size from 20 to 300 nanometers, rendering them ultramicroscopic and invisible under standard light microscopy, which requires electron microscopy for visualization.[8] This acellular nature and small scale underscore their inability to grow or carry out metabolic functions outside a host, positioning them as fundamentally distinct from prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[9] The classification of viruses as living or non-living organisms remains a subject of debate among biologists, centered on established criteria for life such as cellular organization, metabolism, reproduction, growth, response to stimuli, homeostasis, and evolution.[10] Viruses possess genetic material capable of mutation, evolution through natural selection, and transmission of heritable information, fulfilling some life criteria.[11] However, their lack of autonomous reproduction—relying instead on host cells—and absence of independent metabolism lead most scientists to classify them as non-living, though they blur the boundary between biotic and abiotic entities.[12] At a high level, the viral life cycle consists of infection, where the virus attaches to and enters a host cell; replication of the viral genome using host resources; assembly of new viral particles; and release, often through cell lysis or budding, to disseminate to other cells.[13] This cycle enables viruses to propagate efficiently while exploiting host biology without contributing to cellular homeostasis.[14]Viral Components

Viruses are acellular entities composed of a limited set of molecular building blocks, distinguishing them from cellular organisms by their minimalistic design focused on efficient propagation. The core components include a nucleic acid genome encased in a protective protein capsid, with some viruses featuring an outer lipid envelope and specialized appendages. These elements collectively enable genome protection, host recognition, and delivery, while the overall chemical makeup emphasizes proteins as the dominant structural material.[15] The capsid forms a robust protein shell that encases and safeguards the viral genome from environmental degradation, such as nucleases and physical stress. Composed of multiple copies of one or a few virus-encoded proteins arranged with either icosahedral or helical symmetry, the capsid also facilitates initial attachment to host cells via surface-exposed regions. For instance, icosahedral capsids, seen in adenoviruses, consist of 252 capsomeres forming a near-spherical structure approximately 70-90 nm in diameter, while helical capsids, as in tobacco mosaic virus, wind around the genome in a rod-like configuration.[3][16] The viral genome, serving as the hereditary material, consists of either DNA or RNA, which can be single-stranded or double-stranded, linear or circular, and monopartite or segmented. Genome sizes vary widely, from approximately 7.5 kb in single-stranded RNA picornaviruses like poliovirus to over 1.2 Mb in double-stranded DNA mimiviruses, reflecting diverse coding capacities from a handful to over 900 proteins. These genome types underpin the Baltimore classification system, grouping viruses by replication strategies.[3][17][18] Many viruses acquire an envelope, a lipid bilayer derived from modified host cell membranes that surrounds the capsid, providing additional stability and aiding in immune evasion. Embedded in this envelope are virus-encoded glycoproteins that project as spikes, crucial for specific recognition and binding to host receptors; examples include the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase spikes in influenza viruses or the envelope glycoproteins gp120 and gp41 in HIV. Non-enveloped viruses, such as poliovirus, lack this layer and rely solely on the capsid for protection. In enveloped viruses, matrix proteins lie beneath the envelope, bridging it to the capsid and coordinating assembly by linking glycoproteins to the nucleocapsid core.[3][15][19] Certain viruses possess additional specialized structures beyond the basic nucleocapsid or enveloped form. Bacteriophages often feature tails and spikes: a tubular tail for genome injection into bacterial hosts, as in T4 phage with its contractile tail, and tail spikes or fibers for receptor binding to initiate infection. These appendages interrupt capsid symmetry and are absent in most animal viruses but exemplify structural diversity in prokaryotic pathogens.[20][21] Chemically, viral particles are predominantly proteinaceous, with proteins comprising 70-90% of the dry weight in non-enveloped viruses to form the capsid and any internal scaffolds. Nucleic acids account for 5-30% of the mass, varying inversely with genome size; for example, RNA constitutes about 10% in picornaviruses. Enveloped viruses incorporate lipids, typically 30-35% of dry weight, primarily phospholipids and cholesterol derived from the host, alongside minor carbohydrates in glycoproteins. This composition underscores the parasitic nature of viruses, hijacking host resources for structural elements while minimizing their own synthetic burden.[15][22]History

Early Observations

The concept of infectious agents smaller than bacteria emerged from studies on diseases like smallpox and yellow fever during the 18th and 19th centuries, which laid groundwork for understanding viral transmission through observational experiments on contagion and inoculation. Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that exposure to cowpox material could prevent smallpox infection highlighted the role of transmissible agents in disease spread, influencing later ideas about invisible pathogens. Similarly, 19th-century investigations into yellow fever outbreaks in the Americas and Europe revealed patterns of human-to-human transmission via close contact or fomites, though the exact mechanisms remained elusive without knowledge of filterable agents. These efforts shifted medical thinking from miasma theory toward specific contagious principles, setting the stage for virology.[23][24][25] A pivotal advance came in 1892 when Russian scientist Dmitri Ivanovsky conducted filtration experiments on tobacco mosaic disease, a condition affecting plants that caused mottled leaves and stunted growth. He passed sap from infected tobacco plants through a fine porcelain Chamberland filter designed to retain bacteria, yet the filtrate remained infectious when applied to healthy plants, indicating the presence of an ultrafilterable agent smaller than known microbes. This observation challenged the prevailing view that all infectious diseases were caused by visible bacteria, as identified by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch.[26][27] Building on Ivanovsky's findings, Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck replicated and extended the experiments in 1898, confirming the filterable nature of the tobacco mosaic agent while demonstrating its ability to multiply in host tissues without forming bacterial colonies. Beijerinck proposed the term contagium vivum fluidum—a "living infectious fluid"—to describe this self-propagating, non-cellular entity that reproduced only within living cells, distinguishing it from inert chemicals or bacterial products. His work established viruses as contagious agents capable of indefinite reproduction in susceptible hosts, marking a conceptual shift toward recognizing them as distinct pathogens. In the same year, German scientists Friedrich Loeffler and Paul Frosch showed that foot-and-mouth disease in cattle was transmitted by a filterable agent, providing the first evidence of a viral pathogen in animals and extending the concept beyond plants.[28][29][30] Early interpretations often misconstrued these filterable agents as bacterial toxins, enzymes, or fragments of disintegrated bacteria, reflecting the era's limited tools for detection and the assumption that all infections stemmed from microbial cells. For instance, some researchers viewed the tobacco mosaic agent as a soluble toxin produced by unseen bacteria, while others speculated it consisted of bacterial debris too small to filter out. These misconceptions persisted until experimental evidence accumulated, highlighting the need for new paradigms in infectious disease research.[31][28] The first direct visualization of a virus occurred through electron microscopy, enabling observation of these submicroscopic particles. In 1931, Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll developed the first transmission electron microscope, achieving resolutions far beyond light microscopy and opening the door to imaging nanoscale structures. By 1939, Helmut Ruska (Ernst's brother) and colleagues captured the first electron micrographs of tobacco mosaic virus, revealing its rod-shaped particles approximately 300 nm long and 18 nm in diameter, confirming its particulate nature and solidifying viruses as discrete entities rather than mere fluids or toxins.[32][26]Key Milestones in Virology

In 1935, American biochemist Wendell M. Stanley achieved a groundbreaking isolation and crystallization of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), demonstrating that viruses could be purified as crystalline nucleoproteins, which blurred the distinction between living organisms and chemical entities. This work, conducted at the Rockefeller Institute, involved precipitating TMV from infected plant sap using ammonium sulfate and confirming its infectivity after recrystallization, earning Stanley the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for advancing the understanding of viral structure. Between 1915 and 1917, British bacteriologist Frederick Twort and Canadian-French microbiologist Felix d'Hérelle independently discovered bacteriophages, viruses that infect and lyse bacteria. Twort observed a filterable agent causing bacterial colonies to dissolve, while d'Hérelle isolated similar agents from dysentery patients and coined the term "bacteriophage" (bacteria-eater), proposing their potential as antibacterial agents. These findings established phages as model organisms for studying viral replication and genetics, influencing later virological research.[33] A pivotal confirmation of DNA as the genetic material came in 1952 through the Hershey-Chase experiment, conducted by Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase using the T2 bacteriophage infecting Escherichia coli. By radioactively labeling phage DNA with phosphorus-32 and protein coats with sulfur-35, they showed that only the DNA entered bacterial cells to direct viral reproduction, while the protein remained outside, thus resolving debates favoring proteins as hereditary agents.[34] This experiment, performed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, provided conclusive evidence supporting DNA's role in heredity and influenced subsequent molecular biology research. The discovery of reverse transcriptase in the early 1970s revolutionized understanding of retroviruses, with Howard Temin and Satoshi Mizutani identifying the enzyme in Rous sarcoma virus virions, enabling RNA-templated DNA synthesis contrary to the central dogma. Independently, David Baltimore detected the same RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in avian myeloblastosis virus, confirming its presence across retroviral families. This 1970 breakthrough, awarded the 1975 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Temin and Baltimore, laid the foundation for studying RNA tumor viruses and later identifying human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 1983 by teams led by Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, Luc Montagnier, and Robert Gallo, who isolated the retrovirus from AIDS patients. The 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine recognized Barré-Sinoussi and Montagnier's HIV discovery for its impact on combating the global AIDS epidemic. The invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 1983 by Kary Mullis at Cetus Corporation transformed viral detection and molecular virology by enabling exponential amplification of specific DNA sequences from minute samples.[35] First detailed in a 1985 paper by Randall Saiki and colleagues, PCR utilized thermostable Taq polymerase to cycle through denaturation, annealing, and extension, revolutionizing diagnostics for viruses like HIV and hepatitis. Mullis received the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this technique, which became indispensable for viral genome sequencing and epidemiological tracking. In the 21st century, metagenomics unveiled the vast viral diversity on Earth, with estimates from global sampling suggesting approximately 10^{31} virus particles, predominantly bacteriophages in oceans and soils, far exceeding other biological entities. This 2007 quantification by Curtis Suttle, built upon by 2011 metagenomic surveys, highlighted viruses' role in ecosystem dynamics and spurred discoveries of novel viral families through unbiased sequencing. Concurrently, the 2012 development of CRISPR-Cas9 by Jennifer Doudna, Emmanuelle Charpentier, and colleagues repurposed bacterial adaptive immunity into a programmable tool for precise genome editing, with applications in virology including targeted disruption of viral genomes in host cells and engineering antiviral therapies.[36] Since then, CRISPR has facilitated studies of viral replication cycles and vaccine development, earning Doudna and Charpentier the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.Classification

ICTV System

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), established in 1966 as the International Committee on Nomenclature of Viruses (ICNV) under the Virology Division of the International Union of Microbiological Societies and renamed in 1975, maintains a universal system for classifying viruses based on their evolutionary relationships.[37] This framework organizes viruses into a hierarchical taxonomy that is periodically updated through proposals reviewed by study groups and ratified by the ICTV Executive Committee, ensuring a standardized nomenclature and classification that reflects advances in virological research.[38] The system emphasizes phylogenetic coherence, grouping viruses that share common ancestry while accommodating the diversity of viral forms.[39] The ICTV taxonomy employs a Linnaean-inspired hierarchy with ranks including realm (the highest), kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, subfamily, genus, subgenus, and species.[40] In 2018, the realm rank was formally introduced to capture deep evolutionary divergences, with Riboviria established as a realm encompassing RNA viruses that utilize RNA-directed RNA polymerase for replication, unifying diverse groups like coronaviruses and flaviviruses under a monophyletic clade.[41] As of the 2025 taxonomy release (MSL #40 v2), the ICTV recognizes 7 realms, accommodating diverse viral lineages.[42] This addition expanded the taxonomy to better align with genomic evidence of ancient viral lineages, allowing for a more comprehensive partitioning of the virosphere.[43] Classification within the ICTV system relies on multiple criteria, including genome sequence similarity, virion morphology, replication strategies, and host range, with an increasing emphasis on phylogenomic analyses to delineate taxa.[44] For instance, sequence-based metrics such as protein-coding gene conservation and pairwise genetic distances are used to propose new species or higher ranks, supplemented by phenotypic data where available.[45] These criteria ensure that taxa reflect shared evolutionary history rather than superficial traits, though metagenomic data from uncultured viruses often requires integrative approaches to establish monophyly.[46] Representative examples illustrate the system's application: the family Herpesviridae, comprising double-stranded DNA viruses that establish latency in mammalian and avian hosts, falls within the order Herpesvirales and is characterized by enveloped icosahedral virions and serial propagation in cell culture.[47] Similarly, the order Mononegavirales includes non-segmented negative-sense RNA viruses, such as the genus Ebolavirus (with species like Zaire ebolavirus), which features filamentous virions and a broad host range spanning mammals and bats.[48] Despite its robustness, the ICTV system faces challenges from viruses' rapid evolutionary rates, which can generate significant genetic diversity and necessitate frequent taxonomic revisions, and from the prevalence of unculturable viruses discovered via metagenomics, which lack traditional phenotypic data for robust placement.[49] As of the 2025 taxonomy release, the ICTV recognizes over 16,000 species across 3,768 genera and 368 families, reflecting ongoing efforts to incorporate vast genomic datasets while addressing these complexities.[42]Baltimore Classification

The Baltimore classification system, proposed by David Baltimore in 1971, categorizes viruses into seven groups based on the nature of their nucleic acid genome and the mechanism by which they synthesize messenger RNA (mRNA) during replication. This scheme adapts the central dogma of molecular biology—DNA to RNA to protein—to viral life cycles, emphasizing how viruses exploit host machinery to produce mRNA for protein synthesis. Unlike taxonomic systems that prioritize evolutionary relationships, the Baltimore classification focuses on molecular replication strategies, providing a framework to predict the enzymatic requirements and potential therapeutic targets for each viral group. The seven classes are defined as follows:| Class | Genome Type | mRNA Synthesis Mechanism | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Host RNA polymerase transcribes dsDNA directly into mRNA | Adenoviruses, herpesviruses, poxviruses |

| II | Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Host DNA polymerase converts ssDNA to dsDNA intermediate, then transcribes mRNA | Parvoviruses |

| III | Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) | Viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase transcribes one strand into mRNA | Reoviruses |

| IV | Positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) | The +ssRNA genome serves directly as mRNA | Picornaviruses (e.g., poliovirus), coronaviruses |

| V | Negative-sense single-stranded RNA (-ssRNA) | Viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase transcribes -ssRNA into +ssRNA mRNA | Orthomyxoviruses (e.g., influenza), rhabdoviruses (e.g., rabies) |

| VI | Single-stranded RNA with reverse transcriptase (ssRNA-RT) | Reverse transcriptase converts +ssRNA to DNA, which integrates into host genome; host machinery transcribes mRNA from integrated DNA | Retroviruses (e.g., HIV) |

| VII | Double-stranded DNA with reverse transcriptase (dsDNA-RT) | Reverse transcriptase partially transcribes dsDNA to RNA intermediate, then back to DNA; host transcribes mRNA from final DNA | Hepadnaviruses (e.g., hepatitis B virus) |