Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

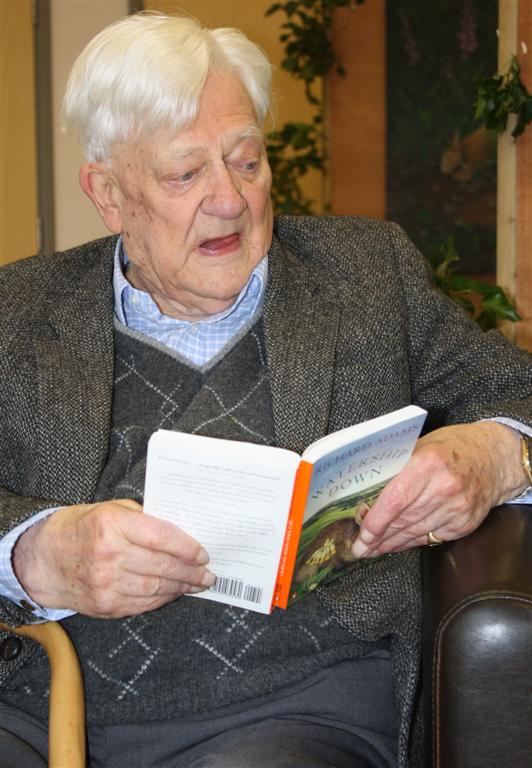

Richard Adams

View on Wikipedia

Richard George Adams FRSL (10 May 1920[a] – 24 December 2016) was an English novelist. He is best known for his debut novel Watership Down which achieved international acclaim. His other works included Maia, Shardik and The Plague Dogs. He studied Modern History at Worcester College, Oxford, before serving in the British Army during World War II. After completing his studies, he joined the British Civil Service. In 1974, two years after Watership Down was published, Adams became a full-time author.[3][4]

Key Information

Early life and education

[edit]Richard Adams was born on 10 May 1920 in Newbury, Berkshire, the son of Lillian Rosa (née Button) and Evelyn George Beadon Adams, a doctor.[1] He attended Horris Hill School from 1926 to 1933 and Bradfield College from 1933 to 1938. In 1938, he went to Worcester College, Oxford, to read Modern History. In July 1940, Adams was called up to join the British Army. He was commissioned into the Royal Army Service Corps[5] and was selected for the Airborne Company, where he worked as a brigade liaison. He served in Palestine, Europe, and East Asia but saw no direct action against either the Germans or the Japanese.[6]

After leaving the army in 1946, Adams returned to Worcester College to continue his studies for a further two years. He received a bachelor's degree in 1948, proceeding MA in 1953.[7]

Civil Service career

[edit]After graduating in 1948, Adams joined the Civil Service, rising to the rank of Assistant Secretary to the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, later part of the Department of the Environment. He began to write his own stories in his spare time, reading them to his children and later on, to his grandchildren.[8]

Writing career

[edit]Adams originally began telling the story that would become Watership Down to his two daughters on a car trip.[9] They eventually insisted that he publish it as a book. He began writing in 1966, taking two years to complete it.[9] In 1972, after four publishers and three writers' agencies turned down the manuscript, Rex Collings agreed to publish the work.[8] The book gained international acclaim almost immediately for reinvigorating anthropomorphic fiction with naturalism.[9][10]

Over the next few years Watership Down sold over a million copies worldwide. Adams won both of the most prestigious British children's book awards, one of six authors to do so: the Carnegie Medal and the Guardian Children's Fiction Prize.[11][12][b] In 1974, following publication of his second novel, Shardik, he left the Civil Service to become a full-time author. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1975.[13]

At one point, Adams served as writer-in-residence at the University of Florida[14] and at Hollins University in Virginia.[3] Adams was the recipient of the inaugural Whitchurch Arts Award for inspiration in January 2010, presented at the Watership Down pub in Freefolk, Hampshire.[15][16] In 2015 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Winchester.[17]

Animal welfare

[edit]Adams was a strong advocate of animal welfare.[18] In 1980, Adams served two years as president of the RSPCA.[19][20][21] He resigned in 1982, commenting that the Society "seemed to be more concerned with each other than with the animals".[18][20] Adams was involved with Cruelty Free International.[22] He was also a patron of Animal Aid.[23]

Besides campaigning against fur, Adams wrote The Plague Dogs to satirise animal experimentation (as well as government and the tabloid press).[24] He also made a voyage through the Antarctic in the company of the ornithologist Ronald Lockley.[25] Just before his 90th birthday, he wrote a new story for a charity book, Gentle Footprints, to raise funds for the Born Free Foundation.[8]

Personal life

[edit]In 1949, Adams married Barbara Elizabeth, daughter of RAF Squadron-Leader Edward Fox Dyke Acland, son of the barrister and judge Sir Reginald Brodie Dyke Acland, whose father, the scientist Henry Wentworth Dyke Acland (himself created a baronet of St Mary Magdalen, Oxford) descended from the Acland baronets of Columb John[26][27] in Devon.

Until his death, Adams lived with his wife in Church Street, Whitchurch, Hampshire, within 10 miles (16 km) of his birthplace. Their daughters, to whom Adams originally related the tales that became Watership Down, are Juliet and Rosamond.[8][28] Adams celebrated his 90th birthday in 2010 with a party at the White Hart in Whitchurch, where Sir George Young presented him with a painting by a local artist. Adams wrote a poetic piece celebrating his home of the past 28 years.[29][30]

Adams died on 24 December 2016 at the age of 96 in Oxford, from complications of heart failure and a blood disorder.[1][31][32][33][34]

Works

[edit]- Watership Down (1972) ISBN 978-0-7432-7770-9

- Shardik (1974) ISBN 978-0-380-00516-1

- Nature Through the Seasons (1975) ISBN 978-0-7226-5007-3

- The Tyger Voyage (1976) ISBN 978-0-394-40796-8, with Nicola Bayley (reprinted 2013, David R. Godine, Publisher, ISBN 978-1-56792-491-6)

- The Plague Dogs (1977) ISBN 978-0-345-49402-3

- The Ship's Cat (1977, text of picture book illustrated by Alan Aldridge) ISBN 978-0-394-42334-0

- Nature Day and Night (1978) ISBN 0-7226-5359-X (with M. D. Hooper)

- The Girl in a Swing (1980) ISBN 978-0-7139-1407-8

- The Iron Wolf and Other Stories (1980), published in the US as The Unbroken Web: Stories and Fables. Color Illustrations by Yvonne Gilbert, b&w illustrations by Jennifer Campbell. ISBN 978-0-517-40375-4

- The Legend of Te Tuna (1982), Sylvester & Orphanos, ISBN 978-0-283-99393-0

- Voyage Through the Antarctic (1982 with Ronald Lockley), Allen Lane ISBN 0-7139-1396-7

- Maia (1984) ISBN 978-0-517-62993-2

- A Nature Diary (1985) ISBN 0-670-80105-4, ISBN 978-0-670-80105-3

- The Bureaucats (1985) ISBN 0-670-80120-8, ISBN 978-0-670-80120-6

- Traveller (1988) ISBN 978-0-394-57055-6

- The Day Gone By (autobiography) (1990) ISBN 978-0-679-40117-9

- Tales from Watership Down (collection of linked stories) (1996) ISBN 978-0-380-72934-0

- The Outlandish Knight (1999) ISBN 978-0-7278-7033-9

- Daniel (2006) ISBN 1-903110-37-8

- "Leopard Aware"[8] in Gentle Footprints (2010) ISBN 978-1-907335-04-4

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b While most sources give Adams's date of birth as 9 May 1920, his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, citing his birth certificate, says he was born on 10 May,[1] as does the 1939 England and Wales Register.[2]

- ^ Alternatively, six authors have won the Carnegie Medal for their Guardian Prize–winning books. Professional librarians confer the Carnegie and select the winner from all British children's books. The Guardian newspaper's prize winner is selected by British children's writers, "peers" of the author who has not yet won it, for one children's (age 7+) or young-adult fiction book. Details regarding author and publisher nationality have varied.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hamley, Dennis (2020). "Adams, Richard George (1920–2016), author". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/odnb/9780198614128.013.111619. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Richard G Adams in the 1939 England and Wales Register". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Structo talks to Richard Adams". Structo. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (27 December 2016). "Richard Adams, Whose Novel 'Watership Down' Became a Phenomenon, Dies at 96". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "No. 35034". The London Gazette (Supplement). 3 January 1941. p. 115.

- ^ Michael D Sharp, Popular Contemporary Writers, Marshall Cavendish Corporation 2006 ISBN 0-7614-7601-6(p.26)

- ^ "ADAMS, Richard George", Who's Who 2008, A & C Black, 2008; (online edition), Oxford University Press, December 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Blezard, Paul (15 May 2010). "Richard Adams: Forever animated by the life of animals". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ a b c Batty, David (28 December 2016). "Richard Adams, Watership Down author, dies aged 96". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Jones, Timothy (27 December 2016). "Watership Down author Richard Adams dies, aged 96". DW. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ (Carnegie Winner 1972) Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Living Archive: Celebrating the Carnegie and Greenaway Winners. CILIP. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ "Guardian children's fiction prize relaunched: Entry details and list of past winners". The Guardian 12 March 2001. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Royal Society of Literature All Fellows". Royal Society of Literature. Archived from the original on 5 March 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ^ "Department of English | Graduate Programs – MFA in Fiction & Poetry". English.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Water under the bridge Wiltshire Society. March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- ^ "Whitchurch Arts Award for inspiration given to Richard Adams (accessed April 2010)". Whitchurcharts.org.uk. 9 May 1920. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ "Inspirational figures celebrated at University of Winchester Graduation ceremonies". The University of Winchester. 17 October 2015. Archived from the original on 28 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Richard Adams: Forever animated by the life of animals". The Independent. 2010.

- ^ "RSPCA President". The Scotsman. 18 June 1980. p. 15. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Animal Book Author Quits". Evening News. 29 September 1982. p. 9. (subscription required)

- ^ Batty, David (2016). "Richard Adams, Watership Down author, dies aged 96". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2024.

- ^ "Richard Adams – a man of stories and animals". Cruelty Free International. 2017. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Spotlight on Cruelty". Leamington Spa Courier. 19 August 1988. p. 2. (subscription required)

- ^ Fezza, Charlemange. "My Afternoon with Richard Adams". www.rabbit.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Adams, Richard; Lockley, Ronald (1982). Voyage Through the Antarctic. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0394528588.

- ^ Burke's Peerage, 1999, vol. 1, pg 26.

- ^ Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, vol. 2, R. Reginald, 1979, pg 790.

- ^ Cooper, Jonathan (11 March 1985). "Richard Adams Follows Up Watership Down and Shardik with An Erotic Epic Called Maia". People. Vol. 23, no. 10.

- ^ "Whitchurch Arts, Celebration of Richard Adams' 90th Birthday". Whitchurcharts.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ Knox, Patrick (20 May 2010). "Party time for Richard as he celebrates 90th". Basingstoke Gazette. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Harrison Smith (28 December 2016). "Richard Adams, best-selling British author of 'Watership Down,' dies at 96". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "Requiescat in Pace". Watership Down Enterprises. 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Watership Down author Richard Adams dies aged 96". BBC News. 27 December 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Richard Adams: The man who turned a story about rabbits into a best-seller". BBC News. 27 December 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

External links

[edit]- Richard Adams at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Richard Adams at the Internet Book List

- Richard Adams at the Internet Book Database of Fiction

- Richard Adams at IMDb

- Portraits of Richard Adams at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Jungian analyst Vera von der Heydt interviewed by novelist Richard Adams in 1978 - CG Jung Institute of Los Angeles

- Richard Adams at Wrecking Ball Press

- Richard Adams's Desert Island Discs appearance - 5 November 1977

Richard Adams

View on GrokipediaRichard George Adams (9 May 1920 – 24 December 2016) was an English novelist renowned for his debut work Watership Down (1972), an anthropomorphic adventure novel depicting a group of rabbits fleeing their warren in search of a new home, which became a global bestseller with over 50 million copies sold.[1][2] Born in Newbury, Berkshire, to a physician father, Adams developed an early affinity for the English countryside that informed his writing, drawing on personal observations of wildlife during family car trips to invent the rabbit protagonists for his young daughters.[1][2] After serving in the British Army during the Second World War with the Royal Army Service Corps and airborne units, Adams pursued a degree in history at Oxford University before entering the civil service, where he rose to assistant secretary in the Department of the Environment by 1974.[1][2] The success of Watership Down, initially rejected by major publishers but championed by a small press, enabled him to resign from government work and write full-time; the novel earned the Carnegie Medal and was adapted into an animated film in 1978.[2] Adams produced subsequent works including Shardik (1974), a fantasy epic, and The Plague Dogs (1977), a critique of animal experimentation, though these received more mixed critical reception.[1][2] A committed advocate for animal welfare, Adams served briefly as president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) in 1980–1982, resigning amid internal disputes over policy, and campaigned against practices like vivisection and the fur trade.[1][2] His oeuvre, blending mythic storytelling with naturalist detail, reinvigorated anthropomorphic fiction while reflecting his firsthand military experiences and environmental concerns, though some later novels incorporated controversial erotic elements that drew criticism.[2]