Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Risk premium

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2011) |

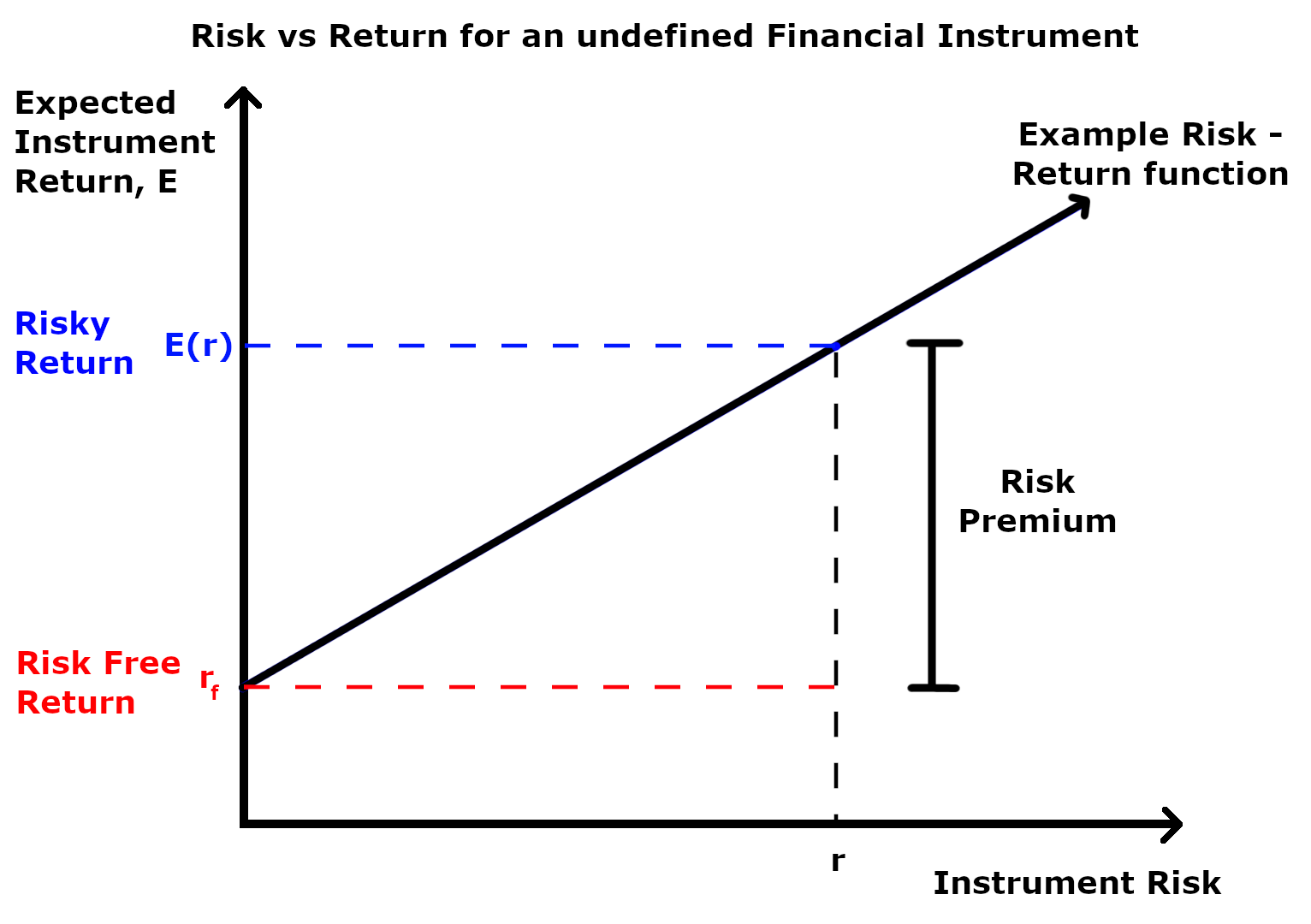

A risk premium is a measure of excess return that is required by an individual to compensate being subjected to an increased level of risk.[1] It is used widely in finance and economics, the general definition being the expected risky return less the risk-free return, as demonstrated by the formula below.[2]

Where is the risky expected rate of return and is the risk-free return.

The inputs for each of these variables and the ultimate interpretation of the risk premium value differs depending on the application as explained in the following sections. Regardless of the application, the market premium can be volatile as both comprising variables can be impacted independent of each other by both cyclical and abrupt changes.[2] This means that the market premium is dynamic in nature and ever-changing. Additionally, a general observation regardless of application is that the risk premium is larger during economic downturns and during periods of increased uncertainty.[3]

There are many forms of risk such as financial risk, physical risk, and reputation risk. The concept of risk premium can be applied to all these risks and the expected payoff from these risks can be determined if the risk premium can be quantified. In the equity market, the riskiness of a stock can be estimated by the magnitude of the standard deviation from the mean.[4] If for example the price of two different stocks were plotted over a year and an average trend line added for each, the stock whose price varies more dramatically about the mean is considered the riskier stock. Investors also analyse many other factors about a company that may influence its risk such as industry volatility, cash flows, debt, and other market threats.[4]

Formal definition in expected utility theory

[edit]In expected utility theory, a rational agent has a utility function that maps sure-outcomes to numerical values, and the agent ranks gambles over sure-outcomes by their expected utilities.

Let the set of possible wealth-levels be . A gamble is a real-valued random variable. The actuarial value of the gamble is just its expectation: . This is independent of any agent.

Let the agent have a utility function , with a wealth-level . The risk-premium of for the agent at wealth-level is , defined as the solution to[5]

Note that the risk-premium depends both on the gamble itself, the agent's utility function, and the wealth-level of the agent. This can be understood intuitively by considering a real gamble. Some people may be quite willing to take the gamble and thus have a low risk-premium, while others are more averse. Further, as one's wealth increases, one is usually less perturbed by the gamble, whose stakes diminishes relative to one's wealth, consequently the risk-premium often decreases as increases, holding constant.

Risk premium application in finance

[edit]The risk premium is used extensively in finance in areas such as asset pricing, portfolio allocation and risk management.[2] Two fundamental aspects of finance, being equity and debt instruments, require the use and interpretation of associated risk premiums with the inputs for each explained below:

Equity instruments

[edit]In the stock market the risk premium is the expected return of a company stock, a group of company stocks, or a portfolio of all stock market company stocks, minus the risk-free rate.[6] The return from equity is the sum of the dividend yield and capital gains and the risk free rate can be a treasury bond yield.[7]

For example, if an investor has a choice between a risk-free treasury bond with a bond yield of 3% and a risky company equity asset, the investor may require a greater return of 8% from the risky company. This would result in a risk premium of 5%. Individual investors set their own risk premium depending on their level of risk aversion.[8] The formula can be rearranged to find the expected return on an investment given a stated risk premium and risk-free rate. For example, if the investor in the example above required a risk premium of 9% then the expected return on the equity asset would have to be 12%.

Debt instruments

[edit]The risk premium associated with bonds, known as the credit spread, is the difference between a risky bond and the risk free treasury bond with greater risk demanding a greater risk premium as compensation.[9]

Risk premium application in banking

[edit]Risk premiums are essential to the banking sector and can provide a large amount of information to investors and customers alike. For instance, the risk premium for a savings account is determined by the bank through the interest that they set on their savings accounts for customers.[10] This less the interest rate set by the central bank provides the risk premium. Stakeholders can interpret a large premium as an indication of increased default risk which has flow on effects such as negatively impacting the public's confidence in the financial system which can ultimately lead to bank runs which is dangerous for an economy.[10]

The risk premium is equally important for a bank's assets with the risk premium on loans, defined as the loan interest charged to customers less the risk free government bond, needing to be sufficiently large to compensate the institution for the increased default risk associated with providing a loan.[11]

Using the risk premium to produce valuations

[edit]One of the most important applications of risk premiums is to estimate the value of financial assets. There are a number of models used in finance to determine this with the most widely used being the Capital Asset Pricing Model or CAPM.[12] CAPM uses investment risk and expected return to estimate a value for the investment. In Finance, CAPM is generally used to estimate the required rate of return for an equity. This required rate of return can then be used to estimate a price for the stock which can be done via a number of methods.[12] The formula for CAPM is:

- CAPM = (The Risk Free Rate) +

- (The Beta of the Security) * (The Market Risk Premium)[13]

In this model, we use the implied risk premium (market return less risk-free rate) and multiply this with the beta of the security. The beta of a security is the measure of a security's volatility relative to the broader market to understand its historical share price movement compared to the market.[12] If the beta of a stock is 1.0 then a 10% increase in the market will translate to a 10% increase in stock price. If the Beta of a stock is 1.5 then a 10% increase in the market will translate to a 15% increase in the stock price and if the beta of a stock is 0.5 a 10% market increase will translate to a 5% stock price increase and likewise with decreases in the market. This beta is generally found via statistical analysis of the share price history of a stock. Therefore CAPM aims to provide a simple model in order to estimate the required return of an investment which uses the theory of risk premiums. This helps to provide investors with a simple means of determining what return an investment should be relative to its risk.[13]

Risk premium application in managerial economics

[edit]The risk premium concept is equally applicable in managerial economics. The risk premium is largely correlated with risk aversion with the larger the risk aversion of an individual or business the larger the risk premium the party will be willing to pay to avoid the risk.[14]

Regarding workers, the risk premium increases as the risk of injury increases and manifests in practice with average wages in dangerous jobs being higher for this reason.[15] Another way in which the risk premium can be interpreted from the workers perspective is that risk is valued by the market, in the form of wage discrepancies between risky and less risky jobs, with a worker able to determine what amount they are willing to forgo to engage in a less risky job.[16] In this instance the risk premium provides insight into the strength of correlation between risk and the average job type earnings with a larger premium potentially suggesting that there is a greater risk and/ or a lack of workers willing to take the risk.[17]

The level of risk associated with the risk premium concept does not need to be physical risk but it can also incorporate risk surrounding the job, such as job security.[18] Higher risk of unemployment is compensated with a higher wage with this being a reason as to why fixed-term contracts generally include a higher wage.[18] CEO's in industries with high volatility are subject to increased risk of dismissal.[19] Dismissed CEO's often undergo a period of unemployment after dismissal and frequently settle for jobs in smaller firms with lower remuneration.[20] Due to this, and assuming there is demand competition within the labor market, they often require a higher remuneration than CEO's in non-volatile industries as a risk premium.[19]

In public goods

[edit]In invasive species management

[edit]The option value of whether to invest in invasive species quarantine and/or management is a risk premium in some models.[21]

In agriculture

[edit]Of crop pathogens

[edit]Farmers cope with crop pathogen risks and losses in various ways, mostly by trading off between management methods and pricing that includes risk premiums. For example in the northern United States, Fusarium head blight is a constant problem. Then in 2000 the release of a multiply-resistant cultivar of wheat dramatically reduced the necessary risk premium. The total planted area of MR wheats was dramatically expanded, due to this essentially costless tradeoff to the new cultivar.[22]

Of investment in genetic research

[edit]Estimates of costs of research and development - including patent costs - of new crop genes and other agricultural biotechnologies must include the risk premium of those which do not ultimately obtain patent approval.[23]

Example of observed risk premium

[edit]Suppose a game show participant may choose one of two doors, one that hides $1,000 and one that hides $0. Further, suppose that the host also allows the contestant to take $500 instead of choosing a door. The two options (choosing between door 1 and door 2, or taking $500) have the same expected value of $500, so no risk premium is being offered for choosing the doors rather than the guaranteed $500.

A contestant unconcerned about risk is indifferent between these choices. A risk-averse contestant will choose no door and accept the guaranteed $500, while a risk-loving contestant will derive utility from the uncertainty and will therefore choose a door.

If too many contestants are risk averse, the game show may encourage selection of the riskier choice (gambling on one of the doors) by offering a positive risk premium. If the game show offers $1,600 behind the good door, increasing to $800 the expected value of choosing between doors 1 and 2, the risk premium becomes $300 (i.e. $800 expected value minus $500 guaranteed amount). Contestants requiring a minimum risk compensation of less than $300 will choose a door instead of accepting the guaranteed $500.

Empirical estimates of risk premium from securities markets

[edit]Schroeder estimated risk premiums ranging from 4.83 to 7.75 percent in securities markets in the United Kingdom and the European Union under multiple models, with most estimates ranging between 6.3 and 7.2 percent.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gagliardini, Patrick; Ossola, Elisa; Scaillet, Olivier (2016). "Time-Varying Risk Premium in Large Cross-Sectional Equity Data Sets". Econometrica. 84 (3): 985–1046. doi:10.3982/ECTA11069.

- ^ a b c Chalamandaris, George; Rompolis, Leonidas S. (2020). "Recovering the market risk premium from higher-order moment risks". European Financial Management. 27 (1): 147–186. doi:10.1111/eufm.12287. S2CID 224941219.

- ^ Graham, John R.; Harvey, Campbell R. (October 2015). "The Equity Risk Premium in 2015". SSRN. SSRN 2611793.

- ^ a b Kenton, Will. "Risk Management in Finance". Investopedia. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ Pratt, John W. (1964). "Risk Aversion in the Small and in the Large". Econometrica. 32 (1/2): 122–136. doi:10.2307/1913738. ISSN 0012-9682. JSTOR 1913738.

- ^ Hunt, Lacy H.; Hoisington, David M. (2003). "Estimating the stock/bond risk premium". Journal of Portfolio Management. 29 (2): 28–34. doi:10.3905/jpm.2003.319870. S2CID 153742349.

- ^ Reichenstein, William; Rich, Steven P. (1993). "The market risk premium and long-term stock returns". Journal of Portfolio Management. 19 (4): 63. doi:10.3905/jpm.1993.409461. S2CID 154215909.

- ^ Díaz, Antonio; Esparcia, Carlos (2019). "Assessing Risk Aversion From the Investor's Point of View". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 1490. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01490. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6614341. PMID 31312157.

- ^ Hollander, Hylton; Guangling, Liu (2016). "Credit spread variability in the U.S. business cycle: The Great Moderation versus the Great Recession". Journal of Banking & Finance. 67: 37–52. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.02.008.

- ^ a b Lall, Martin; Prasad, Ved; Berkman, Henk (2013). "New Zealand finance companies and risk premiums". Accounting & Finance. 54 (4): 1207–1229. doi:10.1111/acfi.12039. S2CID 154699020.

- ^ Adusei, Michael (2019). "The finance–growth nexus: Does risk premium matter?". International Journal of Finance and Economics. 24 (1): 588–603. doi:10.1002/ijfe.1681. S2CID 158303642.

- ^ a b c Danthine, Jean-Pierre. (2015). Intermediate financial theory. Donaldson, John B. (3rd ed.). Oxford, [England]: Elsevier/Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-386549-6. OCLC 1152994506.

- ^ a b McClure, Ben. "Explaining The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ Stapleton, Richard C.; Qi, Zeng (2018). "Downside Risk Aversion and the Downside Risk Premium". The Journal of Risk and Insurance. 85 (2): 379–395. doi:10.1111/jori.12241. hdl:11343/283439. S2CID 158503442.

- ^ Olson, Craig A. (1981). "An Analysis of Wage Differentials Received by Workers on Dangerous Jobs". The Journal of Human Resources. 16 (2): 167–185. doi:10.2307/145507. JSTOR 145507.

- ^ Arnould, Richard J.; Nichols, Len M. (1983). "Wage-Risk Premiums and Workers' Compensation: A Refinement of Estimates of Compensating Wage Differential". The Journal of Political Economy. 91 (2): 332–340. doi:10.1086/261149. S2CID 21755839.

- ^ Cubas, German; Silos, Pedro (2017). "Career choice and the risk premium in the labor market". Review of Economic Dynamics. 26: 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.red.2017.02.009.

- ^ a b Hagen, Tobias (2003). "Do Temporary Workers Receive Risk Premiums? Assessing the Wage Effects of Fixed–term Contracts in West Germany by a Matching Estimator Compared with Parametric Approaches". Labour. 16 (4): 667–705. doi:10.1111/1467-9914.00212.

- ^ a b Peters, Florian S.; Wagner, Alexander F. (2012). "The Executive Turnover Risk Premium". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1140713. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 219335510.

- ^ Fee, C. Edward; Hadlock, Charles J. (2002). "Management Turnover Across the Corporate Hierarchy". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.313381. ISSN 1556-5068. S2CID 219722544.

- ^ Finnoff, David; McIntosh, Chris; Shogren, Jason F.; Sims, Charles; Warziniack, Travis (2010). "Invasive Species and Endogenous Risk". Annual Review of Resource Economics. 2 (1). Annual Reviews: 77–100. doi:10.1146/annurev.resource.050708.144212. ISSN 1941-1340.

- ^ Zhu, Zhanwang; Hao, Yuanfeng; Mergoum, Mohamed; Bai, Guihua; Humphreys, Gavin; Cloutier, Sylvie; Xia, Xianchun; He, Zhonghu (2019). "Breeding wheat for resistance to Fusarium head blight in the Global North: China, USA, and Canada". The Crop Journal. 7 (6). Crop Science Society of China (Elsevier): 730–738. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2019.06.003. ISSN 2214-5141. S2CID 199629483.

- ^ Arnold, Beth E.; Ogielska-Zei, Eva (2002). "Patenting Genes and Genetic Research Tools: Good or Bad for Innovation?". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 3 (1). Annual Reviews: 415–432. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.3.032102.170635. ISSN 1527-8204. PMID 12142363.

- ^ David Schroeder (16 October 2007). "The Implied Equity Risk Premium - An Evaluation of Empirical Methods". KREDIT und KAPITAL. 40 (4): 583–613. ISSN 0023-4591. Wikidata Q106644168..

External links

[edit]- Fundamental Risk versus Systematic Risk Archived 2015-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Hussman Funds – Estimating the Long-Term Return on Stocks – June 1998

- Earnings Quality and the Equity Risk Premium: A Benchmark Model

- Ruben D. Cohen (2002) "The Relationship Between the Equity Risk Premium, Duration and Dividend Yield (download)," Wilmott Magazine, pp 84–97, November issue.

- Ruben D. Cohen "The Long-run Behaviour of the S&P Composite Price Index and its Risk Premium (download)."

![{\displaystyle \mathbb {E} [Z]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4ae460def73cdd7e3fc18d1a4df03c33ce673331)

![{\displaystyle u(w+\mathbb {E} [Z]-\pi )=\mathbb {E} [u(w+Z)].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f252ed6e4893cb980198ddb8220d9230fba9dc4c)