Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stratum

View on Wikipedia

In geology and related fields, a stratum (pl.: strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as either bedding surfaces or bedding planes.[1] Prior to the publication of the International Stratigraphic Guide,[1] older publications have defined a stratum as being either equivalent to a single bed or composed of a number of beds; as a layer greater than 1 cm in thickness and constituting a part of a bed; or a general term that includes both bed and lamina.[2] Related terms are substrate and substratum (pl.substrata), a stratum underlying another stratum.

Characteristics

[edit]

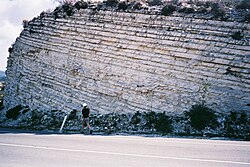

Typically, a stratum is generally one of a number of parallel layers that lie one upon another to form enormous thicknesses of strata.[1] The bedding surfaces (bedding planes) that separate strata represent episodic breaks in deposition associated either with periodic erosion, cessation of deposition, or some combination of the two.[3][4] Stacked together with other strata, individual stratum can form composite stratigraphic units that can extend over hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of the Earth's surface. Individual strata can cover similarly large areas. Strata are typically seen as bands of different colored or differently structured material exposed in cliffs, road cuts, quarries, and river banks. Individual bands may vary in thickness from a few millimeters to several meters or more. A band may represent a specific mode of deposition: river silt, beach sand, coal swamp, sand dune, lava bed, and others.

Types

[edit]In the study of rock and sediment strata, geologists have recognized a number of different types of strata, including bed, flow, band, and key bed.[1][5] A bed is a single stratum that is lithologically distinguishable from other layers above and below it. In the classification hierarchy of sedimentary lithostratigraphic units, a bed is the smallest formal unit. However, only beds that are distinctive enough to be useful for stratigraphic correlation and geological mapping are customarily given formal names and considered formal lithostratigraphic units. The volcanic equivalent of a bed, a flow, is a discrete extrusive volcanic stratum or body distinguishable by texture, composition, or other objective criteria. As in case of a bed, a flow should only be designated and named as a formal lithostratigraphic unit when it is distinctive, widespread, and useful for stratigraphic correlation. A band is a thin stratum that is distinguishable by a distinctive lithology or color and is useful in correlating strata. Finally, a key bed, also called a marker bed, is a well-defined, easily identifiable stratum or body of strata that has sufficiently distinctive characteristics, such as lithology or fossil content, to be recognized and correlated during geologic field or subsurface mapping.[1][5]

Gallery

[edit]-

Strata on a mountain face in the French Alps

-

Rock strata at Depot Beach, New South Wales

-

Rainbow Basin Syncline in the Barstow Formation near Barstow, California. Folded strata.

-

Outcrop of Upper Ordovician limestone and minor shale, central Tennessee

-

Chalk Layers in Cyprus showing classic layered structure

-

Heavy minerals (dark) as thin strata in a quartz beach sand (Chennai, India)

-

Stratified Island near La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Salvador, A. ed., 1994. International stratigraphic guide: a guide to stratigraphic classification, terminology, and procedure. 2nd ed. Boulder, Colorado, The Geological Society of America, Inc., 215 pp. ISBN 978-0-8137-5216-7.

- ^ Neuendorf, K.K.E., Mehl, Jr., J.P., and Jackson, J.A. , eds., 2005. Glossary of Geology 5th ed. Alexandria, Virginia, American Geological Institute. 779 pp. ISBN 0-922152-76-4.

- ^ Davies, N.S.; Shillito, A.P. (2021). "True substrates: The exceptional resolution and unexceptional preservation of deep time snapshots on bedding surfaces". Sedimentology. 68 (7): 3307–3356. doi:10.1111/sed.12900.

- ^ Davies, S.S.; Shillito, A.P. (2018). "Incomplete but intricately detailed: The inevitable preservation of true substrates in a time-deficient stratigraphic record". Geology. 46 (8): 679–682. doi:10.1130/G45206.1.

- ^ a b Murphy, M.A.; Salvador, A. (1999). "International Stratigraphic Guide — An abridged version". Episodes. 22 (4): 255–271. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/1999/v22i4/002.

.jpg/250px-Quebrada_de_Cafayate,_Salta_(Argentina).jpg)

.jpg)