Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

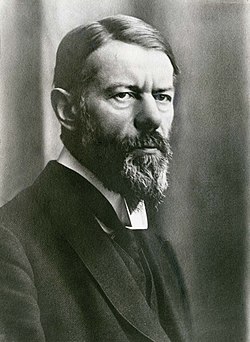

Max Weber

View on Wikipedia

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber (/ˈveɪbər/; German: [ˈveːbɐ] ⓘ;[1] 21 April 1864 – 14 June 1920) was a German sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economist who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the social sciences more generally. His ideas continue to influence social theory and research.

Key Information

Born in Erfurt in 1864, Weber studied law and history in Berlin, Göttingen, and Heidelberg. After earning his doctorate in law in 1889 and habilitation in 1891, he taught in Berlin, Freiburg, and Heidelberg. He married his cousin Marianne Schnitger two years later. In 1897, he had a breakdown after his father died following an argument. Weber ceased teaching and travelled until the early 1900s. He recovered and wrote The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. During the First World War, he initially supported Germany's war effort but became critical of it and supported democratisation. He also gave the lectures "Science as a Vocation" and "Politics as a Vocation". After the war, Weber co-founded the German Democratic Party, unsuccessfully ran for office, and advised the drafting of the Weimar Constitution. Becoming frustrated with politics, he resumed teaching in Vienna and Munich. He died of pneumonia in 1920 at the age of 56, possibly as a result of the post-war Spanish flu pandemic. A book, Economy and Society, was left unfinished.

One of Weber's main intellectual concerns was in understanding the processes of rationalisation, secularisation, and disenchantment. He formulated a thesis arguing that such processes were associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity. Weber also argued that the Protestant work ethic influenced the creation of capitalism in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. It was followed by The Economic Ethics of the World Religions, where he examined the religions of China, India, and ancient Judaism. In terms of government, Weber argued that states were defined by their monopoly on violence and categorised social authority into three distinct forms: charismatic, traditional, and rational-legal. He was also a key proponent of methodological antipositivism, arguing for the study of social action through interpretive rather than purely empiricist methods. Weber made a variety of other contributions to economic sociology, political sociology, and the sociology of religion.

After his death, the rise of Weberian scholarship was slowed by the Weimar Republic's political instability and the rise of Nazi Germany. In the post-war era, organised scholarship began to appear, led by Talcott Parsons. Other American and British scholars were also involved in its development. Over the course of the twentieth century, Weber's reputation grew as translations of his works became widely available and scholars increasingly engaged with his life and ideas. As a result of these works, he began to be regarded as a founding father of sociology, alongside Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, and one of the central figures in the development of the social sciences more generally.

Biography

[edit]Early life and education

[edit]Maximilian Carl Emil Weber was born on 21 April 1864 in Erfurt, Province of Saxony, Kingdom of Prussia, and his family moved to Berlin in 1869.[2] He was the oldest of Max Weber Sr. and Helene Fallenstein's eight children.[3] Over the course of his life, Weber Sr. held posts as a lawyer, civil servant, and parliamentarian for the National Liberal Party in the Prussian Landtag and German Reichstag.[4] This immersed his home in both politics and academia, as his salon welcomed scholars and public figures such as the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey, the jurist Levin Goldschmidt, and the historian Theodor Mommsen. The young Weber and his brother Alfred, who also became a sociologist, spent their formative years in this intellectual atmosphere.[5] Meanwhile, Fallenstein was partly descended from the French Huguenot Souchay family, which had obtained wealth through international commerce and the textile industry.[6] Over time, Weber was affected by the marital and personality tensions between his father, who enjoyed material pleasures while overlooking religious and philanthropic causes, and his mother, a devout Calvinist and philanthropist.[7]

Weber entered the Doebbelinsche Privatschule in Charlottenburg in 1870, before attending the Kaiserin-Augusta-Gymnasium between 1872 and 1882.[8] While in class, bored and unimpressed with his teachers, Weber secretly read all forty of Johann Friedrich Cotta's volumes of the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's works.[9] Before entering university, he read many other classical works, including those by the philosopher Immanuel Kant.[10] For Christmas in 1877, a thirteen-year-old Weber gifted his parents two historical essays, entitled "About the Course of German History, with Special Reference to the Positions of the Emperor and the Pope" and "About the Roman Imperial Period from Constantine to the Migration Period". Two years later, also during Christmastime, he wrote another historical essay, "Observations on the Ethnic Character, Development, and History of the Indo-European Nations". These three essays were non-derivative contributions to the philosophy of history and were derived from Weber's reading of "numerous sources".[11]

In 1882, Weber enrolled in Heidelberg University as a law student, later studying at the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin and the University of Göttingen.[12] Weber's university years were dotted with several periods of military service, the longest of which lasted between October 1883 and September 1884. During this time, he was in Strasbourg and attended classes at the University of Strasbourg that his uncle, the historian Hermann Baumgarten, taught.[13] Weber befriended Baumgarten, who influenced Weber's growing liberalism and criticism of Otto von Bismarck's domination of German politics.[14] Weber was a member of the Burschenschaft Allemannia Heidelberg, a Studentenverbindung ("student association"), and heavily drank beer and engaged in academic fencing during his first few university years.[15] As a result of the latter, he obtained several duelling scars on the left side of his face.[16] His mother was displeased by his behaviour and slapped him after he came home when his third semester ended in 1883. However, Weber matured, increasingly supported his mother in family arguments, and grew estranged from his father.[17]

On 15 May 1886, Weber passed the Referendar examination, a legal training examination.[18] He practiced law and worked as a lecturer simultaneously with his studies.[19] Under the tutelage of Levin Goldschmidt and Rudolf von Gneist, Weber earned his law doctorate in 1889 by writing a dissertation on legal history titled Development of the Principle of Joint Liability and a Separate Fund of the General Partnership out of the Household Communities and Commercial Associations in Italian Cities. It was a part of a longer work, On the History of Commercial Partnerships in the Middle Ages, Based on Southern European Documents, which he published later that year.[20] In the same year, Weber began working on his habilitation, a post-doctoral thesis, with the statistician August Meitzen and completed it two years later. His dissertation, titled Roman Agrarian History and Its Significance for Public and Private Law, focused on the relationship between Roman surveying and Roman agrarian law.[21] Having thus become a Privatdozent, Weber joined the faculty of the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin, lecturing, conducting research, and consulting for the government.[22]

Marriage, early work, and breakdown

[edit]

From 1887 until her declining mental health caused him to break off their relationship five years later, Weber had a semi-engagement with Emmy Baumgarten, the daughter of Hermann Baumgarten.[23] Afterwards, he began a relationship with his second cousin Marianne Schnitger in 1893 and married her on 20 September of that year in Oerlinghausen.[24] The marriage gave Weber financial independence, allowing him to leave his parents' household.[25] They had no children.[26] Marianne was a feminist activist and an author in her own right.[27] Academically, between the completion of his dissertation and habilitation, Weber took an interest in contemporary social policy. He joined the Verein für Socialpolitik ("Association for Social Policy") in 1888.[28] The Verein was an organisation of reformist thinkers who were generally members of the historical school of economics.[29] Weber also involved himself in politics, participating in the founding of the left-leaning Evangelical Social Congress in 1890. It applied a Protestant perspective to the political debate regarding the social question.[30] In the same year, the Verein established a research program to examine the Ostflucht, which was the western migration of ethnically German agricultural labourers from eastern Germany and the corresponding influx of Polish farm workers into it. Weber was put in charge of the study and wrote a large part of the final report, which generated considerable attention and controversy, marking the beginning of his renown as a social scientist.[31]

From 1893 to 1899, Weber was a member of the Pan-German League (Alldeutscher Verband), an organisation that opposed the influx of Polish workers. The degree of his support for the Germanisation of Poles and similar nationalist policies continues to be debated by scholars.[32] Weber and his wife moved to Freiburg in 1894, where he was appointed professor of economics at the University of Freiburg.[33] His 1895 inaugural lecture, "The Nation State and Economic Policy", criticised Polish immigration and argued that the Junkers were encouraging Slavic immigration to serve their economic interests over those of Germany.[34] It influenced the politician Friedrich Naumann to create the National-Social Association, which was a Christian socialist and nationalist political organisation.[35] Weber was pessimistic regarding its potential success, and it dissolved after winning a single Reichstag seat in the 1903 German federal election.[36] In 1896, he accepted an appointment to a chair in economics and finance at Heidelberg University.[37] There, Weber and his wife became the central figures in the eponymous Weber Circle, which included Georg Jellinek, Ernst Troeltsch, and Werner Sombart. Younger scholars, such as György Lukács and Robert Michels, also joined it.[38]

In 1897, Weber had a severe quarrel with his father. Weber Sr. died two months later, leaving the argument unresolved.[39] Afterwards, Weber became increasingly prone to depression, nervousness, and insomnia, which made it difficult for him to fulfill his professorial duties.[40] His condition forced him to seek an exemption from his teaching obligations, which was granted in 1899. He spent time in the Heilanstalt für Nervenkranke Konstanzer Hof in 1898 and in a different sanatorium in Bad Urach in 1900.[41] Weber also travelled to Corsica and Italy between 1899 and 1903 in order to alleviate his illness.[42] He fully withdrew from teaching in 1903 and did not return to it until 1918.[43] Weber thoroughly described his ordeal with mental illness in a personal chronology that his widow later destroyed. Its destruction was possibly caused by Marianne's fear that the Nazis would discredit his work if his experience with mental illness were widely known.[44]

Recovery and reintroduction to academia

[edit]

After recovering from his illness, Weber became an associate editor of the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik (Archive for Social Science and Social Policy) in 1904, alongside his colleagues Edgar Jaffé and Werner Sombart.[45] It facilitated his reintroduction to academia and became one of the most prominent social science journals as a result of his efforts.[46] Weber published some of his most seminal works in this journal, including his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which became his most famous work and laid the foundations for his later research on religion's impact on economic systems' development.[47] Also in 1904, he was invited to participate in the Congress of Arts and Sciences that was held in connection with the Louisiana Purchase Exposition – the World's fair – in St. Louis. He went alongside his wife, Werner Sombart, Ernst Troeltsch, and other German scholars.[48] Taking advantage of the fair, the Webers embarked on an almost three-month-long trip that began and ended in New York City. They travelled throughout the country, from New England to the Deep South. Different communities were visited, including German immigrant towns and African American communities.[49] North Carolina was also visited, as some of Weber's relatives in the Fallenstein family had settled there.[50] Weber used the trip to learn more about America's social, economic, and theological conditions and their relationship with his thesis.[51] Afterwards, he felt that he was unable to resume regular teaching and remained a private scholar, helped by an inheritance in 1907.[52]

Shortly after returning, Weber's attention shifted to the then-recent Russian Revolution of 1905.[53] He learned the Russian language in a few months, subscribed to Russian newspapers, and discussed Russian political and social affairs with the Russian émigré community in Heidelberg.[54] He was personally popular in that community and twice entertained the idea of travelling to Russia. His schedule prevented it, however.[55] While he was sceptical of the revolution's ability to succeed, Weber supported the establishment of a liberal democracy in Russia.[56] He wrote two essays on it that were published in the Archiv.[57] Weber thought that the peasants' desire for land caused the revolution.[58] He discussed the role of the obshchina, rural peasant communities, in Russian political debates. According to Weber, they were difficult for liberal agrarian reformers to abolish due to a combination of their basis in natural law and the rising kulak class manipulating them for their own gain.[59] His general interpretation of the Russian Revolution was that it lacked a clear leader and was not based on the Russian intellectuals' goals. Instead, it was the result of the peasants' emotional passions.[60]

In 1909, having become increasingly dissatisfied with the political conservatism and perceived lack of methodological discipline of the Verein, he co-founded the German Sociological Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie) and served as its first treasurer.[61] Weber associated the society with the Verein and viewed them as not having been competitors.[62] He unsuccessfully tried to steer the association's direction.[63] As part of that, Weber tried to make the Archiv its official journal.[64] He resigned from his position as treasurer in 1912.[65] That was caused by his support for value-freedom in the social sciences, which was a controversial position in the association.[66] Weber – alongside Simmel, Sombart, and Tönnies – placed an abbreviated form of it into the association's statutes, prompting criticism from its other members.[67] Also in 1909, Weber and his wife befriended a former student of his, Else von Richthofen, and the pianist Mina Tobler. After failing to court Richthofen, Weber began an affair with Tobler in 1911.[68]

Later, during the spring of 1913, Weber holidayed in the Monte Verità community in Ascona, Switzerland.[69] While holidaying, he was advising Frieda Gross in her custody battle for her children. He opposed Erich Mühsam's involvement because Mühsam was an anarchist. Weber argued that the case needed to be dealt with by bourgeois reformers who were not "derailed".[70] A year later, also in spring, he again holidayed in Ascona.[71] The community contained several different expressions of the then-contemporaneous radical political and lifestyle reform movements. They included naturism, free love, and Western esotericism, among others. Weber was critical of the anarchist and erotic movements in Ascona, as he viewed their fusion as having been politically absurd.[72]

First World War and political involvement

[edit]After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Weber volunteered for service and was appointed as a reserve officer in charge of organising the army hospitals in Heidelberg, a role he fulfilled until the end of 1915.[73] His views on the war and the expansion of the German Empire changed over the course of the conflict.[74] Early on, he supported the German war effort, believing that the war was necessary to fulfill Germany's duty as a leading state power. In time, however, Weber became one of the most prominent critics of both German expansionism and the Kaiser's war policies.[75] He publicly criticised Germany's potential annexation of Belgium and unrestricted submarine warfare, later supporting calls for constitutional reform, democratisation, and universal suffrage.[76] His younger brother Karl, an architect, was killed near Brest-Litovsk in 1915 while fighting in the war.[77] Weber had previously viewed him negatively but his death made him feel more connected to him.[78]

He and his wife also participated in the 1917 Lauenstein Conferences at Lauenstein Castle in Bavaria.[79] These conferences were planned by the publisher Eugen Diederichs and brought together intellectuals, including Theodor Heuss, Ernst Toller, and Werner Sombart.[80] Weber's presence elevated his profile in Germany and served to dispel some of the event's romantic atmosphere. After speaking at the first one, he became involved in the planning for the second one, as Diederichs thought that the conferences needed an oppositional figure. In this capacity, he argued against the political romanticism that Max Maurenbrecher, a former theologian, espoused. Weber also opposed what he saw as the youth groups and nationalists' excessive rhetoric at Lauenstein, instead supporting German democratisation.[81] For Weber and the younger participants, the conferences' romantic intent was irrelevant to the determination of Germany's future.[82] In November, shortly after the second conference, Weber was invited by the Free Student Youth – a student organisation – to give a lecture in Munich, resulting in "Science as a Vocation".[83] In it, he argued that an inner calling and specialisation were necessary for one to become a scholar.[84] Weber also began a sadomasochistic affair with Else von Richthofen the next year.[85] Meanwhile, she was simultaneously conducting an affair with his brother, Alfred.[86] Max Weber's affairs with Richtofen and Mina Tobler lasted until his death in 1920.[87]

After the war ended, Weber unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the Weimar National Assembly in January 1919 as a member of the liberal German Democratic Party, which he had co-founded.[88] He also advised the National Assembly in its drafting of the Weimar Constitution.[89] While campaigning for his party, Weber critiqued the left and complained about Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg who led the leftist Spartacus League.[90] He regarded the German Revolution of 1918–1919 as responsible for Germany's inability to contest Poland's claims on its eastern territories.[91] His opposition to the revolution may have prevented Friedrich Ebert, the new president of Germany and a member of the Social Democratic Party, from appointing him as a minister or ambassador.[92] Weber also criticized the Treaty of Versailles, which he believed unjustly assigned war guilt to Germany.[93] Instead, he believed that many countries were guilty, not just Germany.[94] In making this case, Weber argued that Russia was the only great power that actually desired the war.[95] He also regarded Germany as not having been culpable for its invasion of Belgium.[96] Overall, Weber's political efforts were unsuccessful, with the exception of his support for a democratically elected and strong presidency.[97] On 28 January 1919, after his electoral defeat, Weber delivered a lecture titled "Politics as a Vocation", which discussed politics.[98] It was prompted by the early Weimar Republic's political turmoil and was requested by the Free Student Youth.[99] Shortly before he left to join the Versailles delegation on 13 May 1919, Weber used his connections with the German National People's Party's deputies to meet with Erich Ludendorff and spent several hours unsuccessfully trying to convince him to surrender himself to the Allies.[100]

Last years

[edit]Frustrated with politics, Weber resumed teaching, first at the University of Vienna in 1918, then at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919.[101] In Vienna, Weber filled a vacant chair in political economy that he had been considered for since October 1917.[102] While there, he gave a lecture titled "Socialism" on the eponymous subject to a group of Austro-Hungarian Army officers.[103] He also had a heated debate with Joseph Schumpeter at the Café Landtmann on whether the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic was usable as a case study for communism.[104] Later, in Munich, Weber was appointed to Lujo Brentano's chair in social science, economic history, and political economy. He accepted the appointment in order to be closer to his mistress, Else von Richthofen.[105] Responding to student requests, he gave a series of economic history lectures. The student transcriptions of it were later edited and published as the General Economic History by Siegmund Hellmann and Melchior Palyi in 1923.[106] In terms of politics, he opposed the pardoning of the Bavarian Minister-President Kurt Eisner's murderer, Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. In response to that, right-wing students disrupted his classes and protested in front of his home.[107] In early 1920, Weber discussed Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West in a seminar, provoking some of his students – who personally knew Spengler – to suggest that he debate Spengler alongside other scholars. They debated for two days in the Munich town hall, but the students felt that the question of how to resolve Germany's post-war issues remained unanswered.[108]

Lili Schäfer, one of Weber's sisters, committed suicide on 7 April 1920 after the pedagogue Paul Geheeb ended his affair with her.[109] Weber respected it, as he thought that her suicide was justifiable and that suicide in general could be honourable.[110] Weber and his wife took in Lili's four children and planned to raise them. He was uncomfortable with his newfound role as a father figure, but he thought that this event fulfilled Marianne as a woman.[111] She later formally adopted the children in 1927.[112] Weber wished for her to stay with the children in Heidelberg or move closer to Geheeb's Odenwaldschule ("Odenwald School") so that he could be alone in Munich with his mistress, Else von Richthofen. He left the decision to Marianne, but she said that only he could make the decision to leave for himself.[113] While this was occurring, Weber began to believe that own life had reached its end.[114]

On 4 June 1920, Weber's students were informed that he had a cold and needed to cancel classes. By 14 June 1920, the cold had turned into influenza and he died of pneumonia in Munich.[115] He had likely contracted the Spanish flu during the post-war pandemic and been subjected to insufficient medical care. Else von Richthofen, who was present by his deathbed alongside his wife, thought that he could have survived his illness if he had been given better treatment.[116] His body was cremated in the Munich Ostfriedhof after a secular ceremony, and the urn that contained his ashes was later buried in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof in 1921. The funeral service was attended by his students, including Eduard Baumgarten and Karl Loewenstein, and fellow scholars, such as Lujo Brentano.[117] At the time of his death, Weber had not finished writing Economy and Society, his magnum opus on sociological theory. His widow, Marianne, helped prepare it for its publication in 1922.[118] She later published a Weber biography in 1926 which became one of the central historical accounts of his life.[119]

Methodology

[edit]Social action was the central focus of Weber's sociology.[120] He also interpreted it as an important part of the field's scientific nature.[121] He divided social action into the four categories of affectional, traditional, instrumental, and value-rational action.[122] Affectional actions were caused by an actor's emotions.[123] Traditional actions were based on tradition.[124] Instrumental actions were calculated attempts to achieve goals.[125] Value-rational actions were attempts to enact one's values.[126] In his methodology, he distinguished himself from Émile Durkheim and Karl Marx in that he primarily focused on individuals and culture.[127] Whereas Durkheim focused on society, Weber concentrated on the individual and their actions. Meanwhile, compared to Marx's support for the material world's primacy over the world of ideas, Weber valued ideas as motivating individuals' actions.[128] His perspective on structure and action and macrostructure differed from theirs in that he was open to the idea that social phenomena could have several different causes and placed importance on social actors' interpretations of their actions.[127]

Verstehen

[edit]The result of what has been said so far is that an "objective" treatment of cultural occurrences, in the sense that the ideal aim of scientific work would be to reduce the empirical [reality] to "laws", is absurd. Not because – as it has often been claimed – the course of cultural processes or, say, processes in the human mind would, "objectively" speaking, be less law-like, but for the following two reasons: (1) knowledge of social laws does not constitute knowledge of social reality, but is only one of the various tools that our intellect needs for that [latter] purpose; (2) knowledge of cultural occurrences is only conceivable if it takes as its point of departure the significance that the reality of life, with its always individual character, has for us in certain particular respects. No law can reveal to us in what sense and in what respects this will be the case, as that is determined by those value ideas in the light of which we look at "culture" in each individual case.

In terms of methodology, Weber was primarily concerned with the question of objectivity and subjectivity, distinguishing social action from social behavior, and noting that social action must be understood through individuals' subjective relationships.[130] According to him, the study of social action through interpretive means or verstehen ("to understand") needed to be based upon understanding the subjective meaning and purpose that individuals attached to their actions.[131] Determining an individual's interpretation of their actions required either empathically or rationally derived evidence.[132] Weber noted that subjectivity's importance in the social sciences made the creation of fool-proof, universal laws harder than in the natural sciences and that the amount of objective knowledge that social sciences were able to create was limited.[133] Overall, he supported objective science as a goal worth striving for but noted that it was ultimately unreachable.[134]

Weber's methodology was developed in the context of wider social scientific methodological debates.[135] The first of which was the Methodenstreit ("method dispute").[136] In it, he was close to historicism, as he thought that social actions were heavily tied to historical contexts.[137] Furthermore, analysing social actions required an understanding of the relevant individuals' subjective motivations.[138] Therefore, his methodology emphasised the use of comparative historical analysis.[139] As such, he was more interested in explaining how an outcome was the result of various historical processes than in predicting those processes' future outcomes.[140] The second debate that shaped Weber's perspective on methodology was the Werturteilsstreit ("value-judgement dispute").[141] This debate was held between 1909 and 1914 on value-judgements in the social sciences. It originated with a Verein für Socialpolitik debate between the supporters and opponents of the idea that ethics was an important consideration in the field of economics.[142] Weber's position was that the social sciences should strive to be value-free.[143] In his view, scholars and students needed to avoid promoting political values in the classroom. Science had no part in choosing values. With regards to economics, he argued that productivity was not a useful scientific concept, as it could impede the proper evaluation of economic phenomena.[144]

Methodological individualism

[edit]The principle of methodological individualism, which holds that social scientists should seek to understand collectivities solely as the result of individual people's actions, can be traced to Weber.[145] The term "methodological individualism" was coined in 1908 by the Austrian-American economist Joseph Schumpeter as a way of referring to Weber's views on how to explain social phenomena.[146] While his research interests placed a strong emphasis on interpreting economic history, Weber's support of methodological individualism represented a break with the historical school and an agreement with the Austrian school's founder, Carl Menger, in the Methodenstreit.[147] In the first chapter of Economy and Society, he argued that only individuals "can be treated as agents in a course of subjectively understandable action".[145] Despite the term's usage of "individualism", Weber did not interpret the individual as being the true source for sociological explanations. Instead, while only individuals could engage in intentional action, they were not necessarily separate from the collective group.[148] He interpreted methodological individualism as having had a close proximity to verstehende ("interpretive") sociology, as actions could be interpreted subjectively. Similarly, it was also related to ideal types in that it involved discussions of abstract and rational models of human behaviour.[149]

Ideal type

[edit]The ideal type was a central concept in Weber's methodology.[150] He argued that they were indispensable for the social sciences.[151] Due their taking of meaning into account, they are unique to the social sciences.[152] The term "ideal type" was derived from Georg Jellinek's use of it.[153] Weber outlined it in "The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy" and the first chapter of Economy and Society.[154] The ideal types' three functions are the formulation of terminology, classifications, and hypotheses.[155] The latter task was the most important of the three.[156] In terms of their construction, an ideal type is a schematic that represents a social action and considers the role of meaning in it.[157] By its nature, it was an exaggeration of an empirical situation through its assumption that the involved individuals were rational, had complete situational knowledge, were completely aware of the situation, were completely aware of their actions, and made no errors.[158] This was then contrasted with empirical reality, allowing the researcher to better understand it.[159] However, ideal types are not direct representations of reality and Weber warned against interpreting them as such.[160] He placed no limits on what ideal types could be used to analyse.[161] Since, for him, rational methodology and science were synonymous with one another, ideal types were constructed rationally.[162]

Value-freedom

[edit]Weber believed that social scientists needed to avoid making value-judgements. Instead, he wanted social scientific research to be value-free.[163] This would give scientists objectivity, but it needed to be combined with an acknowledgement that their research connected with values in different ways.[164] As part of his support for value-freedom, Weber opposed both instructors and students promoting their political views in the classroom.[165] He first articulated it in his writings on scientific philosophy, including "The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy" and "Science as a Vocation".[166] Weber was influenced by Heinrich Rickert's concept of value-relevance.[167] Rickert used it to relate historical objects to values while maintaining objectivity through explicitly defined conceptual distinctions. However, Weber disagreed with the idea that a scholar could maintain objectivity while ascribing to a hierarchy of values in the way that Rickert did, however.[168] His argument regarding value-freedom was connected to his involvement in the Werturteilsstreit.[142] As part of it, he argued in favour of the idea that the social sciences needed to be value-free.[169] During it, he unsuccessfully tried to turn the German Sociological Association into a value-free organisation.[170] Ultimately, that prompted his resignation from it.[66]

Theories

[edit]Rationalisation

[edit]Rationalisation was a central theme in Weber's scholarship.[171] This theme was situated in the larger context of the relationship between psychological motivations, cultural values, cultural beliefs, and the structure of the society.[140] Weber understood rationalisation as having resulted in increasing knowledge, growing impersonality, and the enhanced control of social and material life.[172] He was ambivalent towards rationalisation. Weber admitted that it was responsible for many advances, particularly freeing humans from traditional, restrictive, and illogical social guidelines. However, he also criticised it for dehumanising individuals as "cogs in the machine" and curtailing their freedom, trapping them in the iron cage of rationality and bureaucracy.[173] His studies of the subject began with The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[174] In it, he argued that Protestantism's – particularly Calvinism's – redefinition of the connection between work and piety caused a shift towards rational attempts to achieve economic gain.[175] In Protestantism, piety towards God was expressed through one's secular vocation.[176] The religious principles that influenced the creation of capitalism became unnecessary and it became able to propagate itself without them.[177]

What Weber depicted was not only the secularisation of Western culture, but also and especially the development of modern societies from the viewpoint of rationalisation. The new structures of society were marked by the differentiation of the two functionally intermeshing systems that had taken shape around the organisational cores of the capitalist enterprise and the bureaucratic state apparatus. Weber understood this process as the institutionalisation of purposive-rational economic and administrative action. To the degree that everyday life was affected by this cultural and societal rationalisation, traditional forms of life – which in the early modern period were differentiated primarily according to one's trade – were dissolved.

Weber continued his investigation into rationalisation in later works, notably in his studies on bureaucracy and the classification of legitimate authority into three ideal types – rational-legal, traditional, and charismatic – of which rational-legal was the dominant one in modernity.[179] In these works, Weber described what he saw as society's movement towards rationalisation.[180] Bureaucratic states justified themselves through their own rationality and were supported by expert knowledge which made them rational.[181] Rationalisation could also be seen in the economy, with the development of a highly rational and calculating capitalism. Capitalism's rationality related to its basis in calculation, which separated it from alternative forms of economic organisation.[182] State bureaucracy and capitalism served as the twin pillars of the developing rational society. These changes eliminated the preexisting traditions that relied on the trades.[178] Weber also saw rationalisation as one of the main factors that set the West apart from the rest of the world.[183] Furthermore, The Rational and Social Foundations of Music represented his application of rationalisation to music.[184] It was influenced by his affair with the pianist Mina Tobler and a sense that Western music was the only type that had become harmonic, while other cultures' music was more intense and focused on hearing.[185] Weber argued that music was becoming increasingly rational. In his view, that resulted from new developments in musical instrument construction and simultaneous socio-economic shifts of the different instruments' players.[186]

Disenchantment

[edit]The process of disenchantment caused the world to become more explained and less mystical, moving from polytheistic religions to monotheistic ones and finally to the Godless science of modernity.[187] Older explanations of events relied on the belief in supernatural interference in the material world. Due to disenchantment, this gave way to rational and scientific explanations for events.[188] According to Weber, religious activity began with material world actions that were given magical meanings and associated with vague spirits. Over time, this became increasingly systemised and the spirits became gods, resulting in polytheism and organised religion.[189] Increasing rationality caused Western monotheism to develop, and groups focused on specific gods for political and economic purposes, creating a universal religion.[190] Protestantism encouraged an increased pursuit of rationality that led to the devaluing of itself.[191] It was replaced by modern science, which was thought of as a valid alternative to religious belief.[192] However, modern science also ceased to be a source for universal values, as it could not create values.[193] In its place was a collection of different value systems that could not adequately replace it.[194] This mirrored the previous state of Western polytheism, but differed from it in that its gods were stripped of any mystical qualities that their ancient counterparts had.[195]

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

[edit]The development of the concept of the calling quickly gave to the modern entrepreneur a fabulously clear conscience – and also industrious workers; he gave to his employees as the wages of their ascetic devotion to the calling and of co-operation in his ruthless exploitation of them through capitalism the prospect of eternal salvation.

The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism is Weber's most famous work.[196] It was his first work on how religions affected economic systems' development.[197] In the book, he put forward the thesis that the Protestant work ethic, which was derived from the theological ideas of the Reformation, influenced the development of capitalism.[198] Weber was looking for elective affinities between the Protestant work ethic and capitalism.[199] He argued that the Puritans' religious calling to work caused them to systematically obtain wealth.[200] They wished to prove that they were members of the elect who were destined to go to Heaven.[201] Weber used Benjamin Franklin's personal ethic, as described in his "Advice to a Young Tradesman", as an example of the Protestant sects' economic ethic.[202] Concepts that later became central to his scholarship, such as rationalisation and the ideal type, appeared in the thesis.[174]

Christian religious devotion was historically accompanied by the rejection of mundane affairs, including economic pursuit.[203] Weber argued that the origin of modern capitalism was in the Reformation's religious ideas.[204] According to him, certain types of Protestantism – notably Calvinism – were supportive of the rational pursuit of economic gain and the worldly activities that were dedicated to it, seeing those activities as having been endowed with moral and spiritual significance.[205] The spirit of capitalism was found in the desire to work hard in a way that pleased the worker and signified their worth and originally had a basis in theology.[206] In particular, the Protestant work ethic motivated the believers to work hard, be successful in business, and reinvest their profits in further development rather than frivolous pleasures.[207] Weber thought that self-restraint, hard work, and a belief that wealth could be a sign of salvation were representative of ascetic Protestantism.[208] Ascetic Protestants practiced inner-worldly asceticism and sought to change the world to better reflect their beliefs.[209] The notion of a religious calling, when combined with predestination, meant that each individual had to take action to prove their salvation to themselves.[210] However, the success that these religious principles ultimately created a worldly perspective that removed them as an influence on modern capitalism. As a result, rationalisation entrapped that system's inheritors in a socioeconomic iron cage.[177]

The Economic Ethics of the World Religions

[edit]Weber's work in the field of sociology of religion began with the book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.[211] It continued with the book series The Economic Ethics of the World Religions, which contained The Religion of China, The Religion of India, and Ancient Judaism.[212] However, his sudden death in 1920 left his work incomplete, preventing him from following Ancient Judaism with studies of early Christianity and Islam.[213] The three main themes within the books were: religious ideas' effect on economic activities, the relationship between social stratification and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilisation.[214] His goal was to find reasons for the different developmental paths of the cultures of the Western world and the Eastern world, without making value-judgements, unlike the contemporaneous social Darwinists. Weber simply wanted to explain the distinctive elements of Western civilisation.[215] Weber also proposed a socio-evolutionary model of religious change where societies moved from magic to ethical monotheism, with the intermediatory steps of polytheism, pantheism, and monotheism.[216] According to him, this was the result of growing economic stability, which allowed for professionalisation and the evolution of an increasingly sophisticated priesthood.[217] As societies grew more complex and encompassed different groups, a hierarchy of gods developed. Meanwhile, as their power became more centralised, the concept of a universal God became more popular and desirable.[218]

The Religion of China

[edit]In The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, Weber focused on the aspects of Chinese society that were different from those of Western Europe, especially ones that contrasted with Puritanism. As part of that, he questioned why capitalism had not developed in China.[219] He focused on the issues of Chinese urban development, Chinese patrimonialism and officialdom and Chinese religion and philosophy – primarily Confucianism and Taoism – as the areas in which Chinese significantly differed from European development.[220] According to Weber, Confucianism and Puritanism were superficially similar, but were actually very different from one another.[221] Instead, they were mutually exclusive types of rational thought, each attempting to prescribe a way of life based on religious dogma.[222] Notably, they both valued self-control and restraint and did not oppose accumulation of wealth. However, both of those qualities were simply means to different final goals.[223] Confucianism's goal was "a cultured status position", while Puritanism's goal was to create individuals who were "tools of God". According to Weber, the Puritans sought rational control of the world and rejected its irrationality while Confucians sought rational acceptance of that state of affairs.[224] Therefore, he stated that it was the difference in social attitudes and mentality, shaped by the respective dominant religions, that contributed to the development of capitalism in the West and the absence of it in China.[225]

The Religion of India

[edit]In The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism, Weber dealt with the structure of Indian society and what he interpreted as the orthodox doctrines of Hinduism and the heterodox doctrines of Buddhism and Jainism.[226] In Weber's view, Hinduism in India, like Confucianism in China, was a barrier for capitalism.[227] The Indian caste system, which developed in post-Classical India and served as the source for legitimate social interactions, served as a key part of that.[228] Both Hinduism and the Brahmins' high status upheld the caste system.[229] The Brahmins used their monopoly on education and theological authority to maintain their position.[230] Meanwhile, Hinduism created a psychological justification for it through the cycle of reincarnation.[231] A person's caste position was thought to have been determined by one's past-life actions.[232] As a result, soul advancement and obeying the predetermined order were more important than seeking advancement in the material-world, including economic advancement.[233]

Weber ended his research of society and religion in India by bringing in insights from his previous work on China to discuss the similarities of the Asian belief systems.[234] He noted that these religions' believers used otherworldly mystical experiences to interpret life's meaning.[235] The social world was fundamentally divided between the educated elite who followed the guidance of a prophet or wise man and the uneducated masses whose beliefs were centered on magic. In Asia, there were no messianic prophecies to give both educated and uneducated followers meaning in their regular lives.[236] Weber juxtaposed such Messianic prophecies, notably from the Near East, with the exemplary prophecies found in mainland Asia that focused more on reaching to the educated elites and enlightening them on the proper ways to live one's life, usually with little emphasis on hard work and the material world.[237] It was those differences that prevented Western countries from following the paths of the earlier Chinese and Indian civilisations. His next work, Ancient Judaism, was an attempt to prove this theory.[238]

Ancient Judaism

[edit]In Ancient Judaism, Weber attempted to explain the factors that resulted in the early differences between Eastern and Western religiosity.[239] He contrasted the inner-worldly asceticism developed by Western Christianity with the mystical contemplation that developed in India.[240] Weber noted that some aspects of Christianity sought to conquer and change the world, rather than withdraw from its imperfections.[241] This fundamental characteristic of Christianity originally stemmed from ancient Jewish prophecy.[242] Weber classified the Jewish people as having been a pariah people, which meant that they were separated from the society that contained them.[243] He examined the ancient Jewish people's origins and social structures.[244] In his view, the Israelites maintained order through a covenant with the war god Yahweh and the practice of warrior asceticism.[245] Under Solomon, that changed into a more organised and law-based society than the old confederation was.[246] Religiously, the priests replaced the previous charismatic religious leaders. Weber thought that Elijah was the first prophet to have risen from the shepherds. Elijah promulgated political prophecies and opposed the monarchy.[247]

Theodicy

[edit]Weber used the concept of theodicy in his interpretation of theology and religion throughout his corpus.[248] This involved both his scholarly and personal interests in the subject. It was central to his conception of humanity, which he interpreted as having a connection with finding meaning.[249] Theodicy was a popular subject of study amongst German scholars who sought to determine how a world created by an omnibenevolent and omnipotent being can contain suffering.[250] As part of this tradition, Weber was careful in his study of the subject.[251] Rather than interpreting it through a theological or ethical lens, he interpreted it through a social one.[252] Furthermore, he incorporated Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of ressentiment into his discussion of the topic. However, Weber disagreed with Nietzsche's emotional discussion of ressentiment and his interpretation of it as a Judaism-derived expression of slave morality.[253]

Weber divided theodicy into three main types:[254]

- Persian dualism – God is not all powerful and misfortune comes from outside his power

- Indian doctrine of karma – God is not all powerful and misfortune comes from inside oneself

- Doctrine of predestination – Only a chosen few will be saved from damnation

Weber defined the importance of societal class within religion by examining the difference between the theodicies of fortune and misfortune and to what class structures they apply.[255] The theodicy of fortune related to successful people's desire to prove that they deserved it. They were also prone to not being satisfied with what they already had and wished to avoid the notion that they were illegitimate or sinful.[256] Those who were unsuccessful in life believed in the theodicy of misfortune, believing wealth and happiness would later be divinely granted to those who deserved it.[257] Another example of how this belief of religious theodicy influenced class was that those of lower economic status tended towards deep religiousness and faith as a way to comfort themselves and provide hope for a more prosperous future, while those of higher economic status preferred the sacraments or actions that proved their right to possess greater wealth.[258]

The state, politics, and government

[edit]Weber defined the state as an entity that had a monopoly on violence. This meant that the state could legitimately use force to preserve itself within a given area.[259] He also proposed that politics was the sharing of state power and influencing the distribution thereof between states and between groups within a state.[260] Weber's definition of a politician required that they have passion, judgement, and responsibility.[261] He divided action into the oppositional gesinnungsethik and verantwortungsethik (the "ethic of ultimate ends" and the "ethic of responsibility").[262] A verantwortungsethik adherent justified their actions through their consequences. Meanwhile, a gesinnungsethik adherent justified their actions through their ideals.[263] While Weber thought that an ideal politician possessed both of them, he associated them with different types of people and mindsets.[264] Combining them required that a politician be passionate about their goals and pragmatic about achieving them.[265]

Weber distinguished three ideal types of legitimate authority:[266]

- Charismatic authority – Familial and religious

- Traditional authority – patriarchalism, patrimonialism, feudalism

- Rational-legal authority – Modern law and state, bureaucracy

In his view, all historical relationships between rulers and ruled contained these elements, which could be analysed on the basis of this tripartite classification of authority.[267] Charismatic authority was held by individuals who held power through their charisma, meaning that their power originated from extraordinary personal qualities. It was unstable, as it resisted institutionalisation and relied on the leader's success.[268] Over time, it was forced to be routinised into more structured forms of authority. An administrative structure would be formed by the charismatic leader's followers.[269] Traditional authority was based on loyalty to preestablished traditions and those who held authority as a result of those traditions.[270] For Weber, patriarchalism – the rule by a patriarch over a family – was the most important variety of traditional authority.[271] Patrimonialism – a closely related concept to patriarchalism – was a type of traditional authority where rulers treated the government and military as extensions of their households.[272] Rational-legal authority relied on bureaucracy and belief in both the legality of the society's rules and the legitimacy of those who held power as a result of those rules.[273] Unlike the other types of authority, it developed gradually. That was the result of legal systems ability to exist without charismatic individuals or traditions.[274]

Bureaucracy

[edit]Weber's commentary on societal bureaucratisation is one of the most prominent parts of his work.[275] According to him, bureaucracy was the most efficient societal organisation method and the most formally rational system. It was necessary for modern society to function and would be difficult to destroy.[276] Bureaucratic officials felt superior to non-bureaucrats, had a strong sense of duty, and had fixed salaries that disinclined them to pursue monetary acquisition. Bureaucracy was less likely to be found among elected officials.[277] Furthermore, Bureaucracy's treatment of all people without regard for individuals suited capitalism well.[278] It was also a requirement for both modern capitalism and modern socialism to exist.[279] This depersonalisation related to its increased efficiency. Bureaucrats could not openly make arbitrary decisions or base them on personal favours.[280] As the most efficient and rational way of organising, bureaucratisation was the key part of rational-legal authority. Furthermore, he saw it as the key process in the ongoing rationalisation of Western society.[281]

Weber listed six characteristics of an ideal type of bureaucracy:[282]

- It was in a fixed area that was governed by rules

- Bureaucracies were hierarchical

- Its actions were based on written documents

- Expert training was required

- Bureaucrats were completely devoted to their work

- The system relied on basic rules that were learnable

The development of communication and transportation technologies made more efficient administration possible and popularly requested. Meanwhile, the democratisation and rationalisation of culture resulted in demands that the new system treat everyone equally.[283] Weber's ideal type of bureaucracy was characterised by hierarchical organisation, delineated lines of authority in a fixed area of activity, action taken on the basis of written rules, bureaucratic officials needing expert training, rules being implemented neutrally, and career advancement depending on technical qualifications judged by organisations.[284] While arguing that bureaucracy was the most efficient form of organisation and was indispensable for the modern state, Weber was also critical of it. In his view, an inescapable bureaucratisation of society would happen in the future. He also thought that a hypothetical victory of socialism over capitalism would have not prevented that.[285] Economic and political organisations needed entrepreneurs and politicians in order to counteract bureaucrats. Otherwise, they would be stifled by bureaucracy.[279]

Social stratification

[edit]Weber also formulated a three-component theory of stratification that contained the conceptually distinct elements of class, status, and party.[286] This distinction was most clearly described in his essay "The Distribution of Power Within the Gemeinschaft: Classes, Stände, Parties", which was first published in his book Economy and Society.[287] Status served as one of the central ways in which people were ranked in society. As part of it, issues of honour and prestige were important.[288] With regards to class, the theory placed heavy emphasis on class conflict and private property as having been key to its definition.[289] While Weber drew upon Marx's interpretation of class conflict in his definition of class, he did not see it as having defined all social relations and stratification.[290] Political parties were not given as much attention by Weber as the other two components were, as he thought that they were not particularly effectual in their actions. Their purpose was to seek power to benefit their members materially or ideologically.[291]

The three components of Weber's theory were:[286]

- Social class – Based on an economically determined relationship with the market

- Status (Stand) – Based on non-economic qualities such as honour and prestige

- Party – Affiliations in the political domain

Weber's concept of status emerged from his farm labour and the stock exchange studies, as he found social relationships that were unexplainable through economic class alone. The Junkers had social rules regarding marriage between different social levels and farm labourers had a strong sense of independence, neither of which was economically based.[292] Weber maintained a sharp distinction between the terms "status" and "class", although non-scholars tend to use them interchangeably in casual use.[293] Status and its focus on honour emerged from the Gemeinschaft, which denoted the part of society where loyalty originated from. Class emerged from the Gesellschaft, a subdivision of the Gemeinschaft that included rationally driven markets and legal organisations. Parties emerged from a combination of the two.[294] Weber interpreted life chances, the opportunities to improve one's life, as a definitional aspect of class. They related to the differences in access to opportunities that different people might have had in their lives.[295] The relationship between status and class was not straightforward. One of them could lead to the other, but an individual or group could have success in one but not the other.[296]

The vocation lectures

[edit]Towards the end of his life, Weber gave two lectures, "Science as a Vocation" and "Politics as a Vocation", at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich on the subjects of the scientific and political vocations. The Free Student Youth, a left-liberal student organisation, had their spokesperson, Immanuel Birnbaum, invite him to give the lectures.[297] In "Science as a Vocation", he argued that a scholar needed to possess an inner calling. Weber thought that only a particular type of person was able to have an academic career, stating that the path forward in scholarship required the scholar to be methodical in their research and understand that they might not succeed. Specialisation was also an aspect of modern scholarship that a scholar needed to engage in.[84] Disenchantment and intellectual rationalisation were major aspects of his commentary on the scholar's role in modernity. These processes resulted in scholarship's value being questioned. Weber argued that scholarship could provide certainty through its starting presumptions, despite its inability to give absolute answers.[298] Meanwhile, "Politics as a Vocation" commented on the subject of politics.[98] Weber was responding to the early Weimar Republic's political instability. He argued that politicians had passion, judgement, and responsibility.[299] There was also a division between conviction and responsibility. While these two concepts were sharply divided, it was possible for single individual – particularly the ideal politician – to possess both of them.[99] He also divided legitimate authority into the three categories of traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal authority.[300] Towards the lecture's end, he described politics as "a slow, powerful drilling through hard boards".[301] Ultimately, Weber thought that the political issues of his day required consistent effort to resolve, rather than the quick solutions that the students preferred.[302]

The City

[edit]The origin of a rational and inner-worldly ethic is associated in the Occident with the appearance of thinkers and prophets ... who developed in a social context that was alien to the Asiatic cultures. This context consisted of the political problems engendered by the bourgeois status-group of the city, without which neither Judaism, nor Christianity, nor the development of Hellenistic thinking are conceivable.

As part of his overarching effort to understand the Western world's unique development, Weber wrote a general study of the European city and its development in antiquity and the Middle Ages titled The City.[304] According to him, Christianity broke the kinship traditional bonds by causing its believers to participate in the religion as individuals. However, the institutions that formed as a result of this process were secular in nature.[305] He also saw the rise of a unique form of non-legitimate domination in medieval European cities that successfully challenged the existing forms of legitimate domination – traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal – that had prevailed until then in the medieval world.[306] These cities were previously under the jurisdiction of several different entities that were removed as they became autonomous. That process was caused by the granting of privileges to newer cities and the usurpation of authority in older ones.[307]

Economics

[edit]Weber primarily regarded himself as an economist, and all of his professorial appointments were in economics, but his contributions to that field were largely overshadowed by his role as a founder of modern sociology.[308] As a political economist and economic historian, Weber belonged to the German historical school of economics, represented by academics such as Gustav von Schmoller and his student Werner Sombart.[309] While Weber's research interests were largely in line with this school, his views on methodology and marginal utility significantly diverged from those of the other German historicists. Instead, they were closer to those of Carl Menger and the Austrian school of economics, the historical school's traditional rivals.[310] The division caused by the Methodenstreit caused Weber to support a broad interpretation of economics that combined economic theory, economic history, and economic sociology in the form of Sozialökonomik ("social economics").[311]

Economy and Society

[edit]

Weber's magnum opus Economy and Society is an essay collection that he was working on at the time of his death in 1920.[312] It included a wide range of essays dealing with Weber's views regarding sociology, social philosophy, politics, social stratification, world religion, diplomacy, and other subjects.[313] The text was largely unfinished, outside of the first three chapters. These chapters were written between 1919 and 1920.[314] They relate to verstehende sociology, economic sociology, authority, and class and status groups, respectively.[315] The first chapter is one of the two portions of the text that Weberian scholars consult most frequently – alongside the third chapter – and moved from a discussion of individuals' social actions to the centrality of the monopoly on violence to the state.[316] Meanwhile, the second chapter is less discussed, as it represented a type of economic theory that had fallen out of style amongst economists after the 1930s.[317] It presented an analytical economic history that contained a discussion of the origins of capitalism and supported the idea that the Austrian and historical schools of economics could have a methodological synthesis.[318] Chapter three focused on Weber's tripartite definition of legitimate authority.[319] Since the final chapter was unfinished, it was largely a brief set of classifications of classes and Stände ("statuses").[320]

After Weber's death, the final organisation and editing of the book fell to his widow Marianne. She was assisted by the economist Melchior Palyi. The resulting volume was published in 1922 and was titled Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft.[321] It also included additional texts that were generally written between 1909 and 1914 that his widow had found amongst his belongings.[322] In 1956, the German jurist Johannes Winckelmann edited and organised a revised 4th edition of Economy and Society, later editing a 5th edition of it in 1976.[323] Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich edited an English translation of the work in 1968. It was based on Winckelmann's 1956 edition of the text that he had revised in 1964.[324] The Max Weber-Gesamtausgabe editors published Economy and Society in six parts, with the first devoted to the first four chapters thereof. The remaining five parts were organised in chronological order based on when they were written.[325] In 2023, Keith Tribe published a revised English translation of the Max Weber-Gesamtausgabe edition of its first four chapters.[326]

Marginal utility

[edit]Unlike other historicists, Weber accepted marginal utility and taught it to his students.[327] His overall economic sociology was based on it.[328] In 1908, Weber published an article, "Marginal Utility Theory and 'The Fundamental Law of Psychophysics'", in which he argued that marginal utility and economics were not based on psychology.[329] As part of that, he disputed Lujo Brentano's claim that marginal utility reflected the form of the psychological response to stimuli as described by the Weber–Fechner law.[330] He rejected the idea that marginal utility and economics were dependent on psychophysics.[330] In general, Weber disagreed with the idea that economics relied on another field.[331] He also included a similar discussion of marginal utility in the second chapter of Economy and Society. Both marginal utility and declining utility's roles in his writings were implied through his usage of instrumentally rational action in that chapter.[332]

Economic calculation

[edit]Like his colleague Werner Sombart, Weber regarded economic calculation, particularly double-entry bookkeeping, as having played a significant role in rationalisation and the development of capitalism.[333] Weber's preoccupation with the importance of economic calculation led him to critique socialism as lacking a mechanism to efficiently allocate resources to satisfy human needs.[334] Otto Neurath, a socialist thinker, thought that prices would not exist and central planners would use in-kind, rather than monetary, economic calculation in a completely socialised economy.[335] According to Weber, this type of coordination was inefficient because it was incapable of solving the problem of imputation, which related to the difficulties in accurately determining the relative values of capital goods.[336] Weber wrote that the value of goods had to be determined in a socialist economy. However, there was no clear method for doing so in that economic system. Planned economies were, therefore, irrational.[337] At approximately the same time, Ludwig von Mises independently made the same argument against socialism.[338] Weber himself significantly influenced Mises, whom he had befriended when they were both at the University of Vienna in the spring of 1918. However, Mises ultimately regarded him as a historian, rather than an economist.[339]

Inspirations

[edit]Weber was strongly influenced by German idealism, particularly by neo-Kantianism. He was exposed to it by Heinrich Rickert, who was his professorial colleague at the University of Freiburg.[340] The neo-Kantian belief that reality was essentially chaotic and incomprehensible, with all rational order deriving from the way the human mind focused its attention on certain aspects of reality and organised the resulting perceptions was particularly important to Weber's scholarship.[341] His opinions regarding social scientific methodology showed parallels with the work of the contemporary neo-Kantian philosopher and sociologist Georg Simmel.[342] Weber was also influenced by Kantian ethics more generally, but he came to think of them as being obsolete in a modern age that lacked religious certainties.[343] His interpretation of Kant and neo-Kantianism was pessimistic as a result.[344]

Weber was responding to Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy's effect on modern thought. His goal in the field of ethics was to find non-arbitrarily defined freedom in what he interpreted as a post-metaphysical age. That represented a division between the parts of his thought that represented Kantianism and Nietzscheanism.[345] After his debate with Oswald Spengler in 1920, Weber said that the world was significantly intellectually influenced by Nietzsche and Marx.[346] In The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and "Science as a Vocation", Weber negatively described "die 'letzten Menschen'" ("the 'last men'"), who were Nietzschean "specialists without spirit" who he warned about in both texts.[347] Similarly, he also used Nietzsche's concept of ressentiment in his discussion of theodicy, but he interpreted it differently. Weber disliked Nietzsche's emotional approach to the subject and did not interpret it as a type of Judaism-derived slave morality.[348]

While a student in Charlottenburg, Weber read all forty of Johann Friedrich Cotta's volumes of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe works, which later influenced his methodology and concepts.[9] For him, Goethe was one of the seminal figures in German history.[349] In his writings, including The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber quoted Goethe on several occasions.[350] His usage of "elective affinity" in his writings may have been derived from Goethe, as one of Goethe's works used it as its title.[351] Weber was also influenced by Goethe's usage of the Greek daimon ("fate"). That concept influenced Weber's perspective that one's fate was inevitable and that one was able to use experience to create intellectual passion.[352] He thought that Goethe, his Faust, and Nietzsche's Zarathustra were figures that represented the Übermensch and expressed the quality of human action by ceaselessly striving for knowledge.[353]

Karl Marx's writings and socialist thought in academia and active politics were also major influences on Weber's works.[354] While Weber agreed with Marx on the importance of social conflict, he did not think that it would destroy a society if the traditions that upheld it were valued more than it was. Furthermore, he thought that a social conflict would have been resolvable within the preexisting social system.[355] Writing in 1932, Karl Löwith contrasted the work of Marx and Weber, arguing that both were interested in the causes and effects of Western capitalism, but they viewed it through different lenses. Marx viewed capitalism through the lens of alienation, while Weber interpreted it through the concept of rationalisation.[356] Weber also expanded Marx's interpretation of alienation from the specific idea of the worker who was alienated from his work to similar situations that involved intellectuals and bureaucrats.[357] Scholars during the Cold War frequently interpreted Weber as "a bourgeois answer to Marx", but he was instead responding to the issues that were relevant to the bourgeoisie in Wilhelmine Germany. In that regard, he focused on the conflict between rationality and irrationality.[358]

Legacy

[edit]Alongside Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, Weber is commonly regarded as one of modern sociology's founders.[359] He was instrumental in developing an antipositivist, hermeneutic, tradition in the social sciences.[360] Weber influenced many scholars across the political spectrum.[361] Left-leaning social theorists – such as Theodor W. Adorno, Max Horkheimer, György Lukács, and Jürgen Habermas – were influenced by his discussion of modernity and its friction with modernisation.[362] As part of that, his analysis of modernity and rationalisation significantly influenced the Frankfurt School's critical theory.[363] Right-leaning scholars – including Carl Schmitt, Joseph Schumpeter, Leo Strauss, Hans Morgenthau, and Raymond Aron – emphasised different elements of his thought. They placed importance on his discussion of strong leaders in democracy, political ethics' relationship with value-freedom and value-relativism, and combating bureaucracy through political action.[345] The scholars who have examined his works philosophically, including Strauss, Hans Henrik Bruun, and Alfred Schütz, have traditionally looked at them through the lens of Continental philosophy.[364]

Weber studies

[edit]Weberian scholarship's beginnings were delayed by the disruption of academic life in the Weimar Republic. Hyper-inflation caused Weber's support for parliamentary democracy to be countered by the declining respect that German professors had for it.[365] Their alienation from politics caused many of them to become pessimistic and closer to the historical viewpoints espoused by Oswald Spengler in his The Decline of the West.[366] Furthermore, universities increasingly came under state control and influence, which accelerated after the Nazi Party took power. The previously dominant style of sociology, that of Alfred Vierkandt and Leopold von Wiese, was largely replaced by a sociology that was dominated by support for the Nazis. Hans Freyer and Othmar Spann were representative of that movement, while Werner Sombart began to support collectivism and Nazism.[367] The Nazi Party's rise had marginalised Weber's scholarship in the German academy.[368] However, some Weberian scholars had left Germany during this time, with most of them settling in the United States and the United Kingdom.[369]

These scholars entered American and British academia when Weber's writings, such as the General Economic History, were beginning to be translated into English.[370] Talcott Parsons, an American scholar, was influenced by his readings of Weber and Sombart as a student in Germany during the 1920s.[371] He obtained permission from Marianne Weber to publish a translation of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in his 1930 essay collection, the Collected Essays on the Sociology of Religion.[372] This translated version, which the publisher heavily edited, was not initially successful.[373] Parsons used this translation as part of his effort to create an academic sociology, which resulted in his 1937 book The Structure of Social Action.[374] In it, Parsons argued that Weber and Durkheim were foundational sociologists.[375] However, his book was not successful until after the Second World War.[376] He then published a translation of Economy and Society as The Theory of Social and Economic Organization.[377] Parsons's increasing scholarly prominence led to this volume's own elevated influence.[376] Other translations began to appear, including C. Wright Mills and Hans Gerth's From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology in 1946, which was a collection of excerpts from Weber's writings.[378] In the last year of the decade, Edward Shils edited a translation of Weber's Collected Essays on Methodology, which was published as The Methodology of the Social Sciences.[379]

As the 1940s ended, Weber's scholarly reputation rose as a result of scholarly interpretations of it through the lenses of Parsons's structural functionalism and Mills's conflict theory.[380] Over the course of the following decades, continued publications of translations of Weber's works began to appear, including ones on law, religion, music, and the city. Despite the translations' flaws, it became possible to obtain a largely complete view of Weber's scholarship. That was still impeded by the unorganised publishing of the translations, which prevented scholars from knowing the connections between the different texts.[381] In 1968, a complete translation of Marianne Weber's prepared version of Economy and Society was published.[382] While an interpretation of Weber that was separate from Parson's structural functionalism began with From Max Weber, a more political and historical interpretation was forwarded by Reinhard Bendix's 1948 Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait, Ralf Dahrendorf's 1957 Class and Conflict in an Industrial Society, and John Rex's 1962 Key Problems in Sociological Theory. Raymond Aron's interpretation of Weber in his 1965 text, Main Currents in Sociological Thought, gave an alternative to Parson's perspective on the history of sociology. Weber was framed as one of the three foundational figures, the other two were Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim. Anthony Giddens solidified that interpretation with his 1971 Capitalism and Modern Social Theory. After the 1970s ended, more of Weber's less prominent publications were published. That effort coincided with the continued writing of critical commentaries on his works and idea, including the creation of a scholarly journal in 2000, Max Weber Studies, that is devoted to such scholarship.[383]

Max Weber-Gesamtausgabe

[edit]

The idea of publishing a collected edition of Weber's complete works was pushed forward by Horst Baier in 1972. A year later, the Max Weber-Gesamtausgabe, a multi-volume set of all of his writings, began to take shape.[384] Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Wolfgang Schluchter, Johannes Winckelmann, M. Rainer Lepsius, and Horst Baier were the initial editors. After Mommsen's death in 2004, Gangolf Hübinger succeeded him.[385] Winckelmann, Lepsius, and Baier also died before its completion.[386] The writings were organised in a combination of chronological order and by subject, with the material that Weber did not intend to publish in purely chronological order.[387] The final editions of each text were used, with the exception of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, which was published in both its first and final forms.[388] Mohr Siebeck was selected to publish the volumes.[389] The project was presented to the academic community in 1981 with the publication of a prospectus that was colloquially referred to as the "green brochure". It outlined the series' three sections: "Writings and Speeches", "Letters", and "Lecture Manuscripts and Lecture Notes".[390] Four years later, the project entered publication.[391] It concluded in June 2020 and contains forty-seven volumes, including two index volumes.[392]

Bibliography

[edit]See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ritzer & Wiedenhoft Murphy 2019, p. 32; Newman 2017, p. 175.

- ^ Kaesler 2014, pp. 22, 144–145; Kim 2024; Radkau 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Kaelber 2003, p. 38; Radkau 2009, p. 11; Kaesler 2014, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Kaelber 2003, p. 38; Radkau 2009, p. 5; Honigsheim 2017, p. 100.

- ^ Kaesler 1988, pp. 2–3, 14; Radkau 2009, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kaesler 2014, pp. 68, 129–137; Radkau 2009, p. 9; Kim 2024.

- ^ Radkau 2009, pp. 54, 62; Kaelber 2003, pp. 38–39; Ritzer 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Kaesler 2014, pp. 176–178; Radkau 2009, p. 561.

- ^ a b Kaesler 1988, p. 2; McKinnon 2010, pp. 110–112; Kent 1983, pp. 297–303.

- ^ Kaesler 1988, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Sica 2017, p. 24; Kaesler 2014, p. 180.

- ^ Radkau 2009, pp. 31–33; Bendix & Roth 1977, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Kaelber 2003, p. 30; Radkau 2009, pp. 562–564.

- ^ Mommsen & Steinberg 1984, pp. 2–9; Kaelber 2003, p. 36; Radkau 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Radkau 2009, pp. 31–35; Kaesler 2014, pp. 191, 200–202.