Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

CP/M-86

View on Wikipedia

| CP/M-86 | |

|---|---|

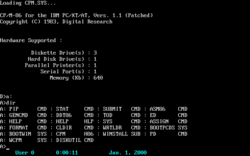

A screenshot of CP/M-86 for the IBM PC/XT/AT Version 1.1 | |

| Developer | Digital Research, Inc. / Gary Kildall / Kathryn Strutynski |

| OS family | CP/M |

| Working state | Historic |

| Source model | Originally closed source, now open source[1] |

| Initial release | November 1981[2] |

| Available in | English |

| Supported platforms | Intel 8086 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic kernel |

| Default user interface | Command-line interface |

| License | Originally proprietary, now BSD-like[citation needed] |

| Preceded by | (CP/M-80 2.2) |

| Succeeded by | Concurrent CP/M-86 3.0 |

CP/M-86 is a discontinued version of the CP/M operating system that Digital Research (DR) made for the Intel 8086 and Intel 8088. The system commands are the same as in CP/M-80. Executable files used the relocatable .CMD file format.[nb 1] Digital Research also produced a multi-user multitasking operating system compatible with CP/M-86, MP/M-86, which later evolved into Concurrent CP/M-86. When an emulator was added to provide PC DOS compatibility, the system was renamed Concurrent DOS, which later became Multiuser DOS, of which REAL/32 is the latest incarnation. The FlexOS, DOS Plus, and DR DOS families of operating systems started as derivations of Concurrent DOS as well.

History

[edit]Digital Research's CP/M-86 was originally announced to be released in November 1979, but was delayed repeatedly.[3] When IBM contacted other companies to obtain components for the IBM PC, the as-yet unreleased CP/M-86 was its first choice for an operating system because CP/M had the most applications at the time. Negotiations between Digital Research and IBM quickly deteriorated over IBM's non-disclosure agreement and its insistence on a one-time fee rather than DRI's usual royalty licensing plan.[4] After discussions with Microsoft, IBM decided to use 86-DOS (QDOS), a CP/M-like operating system that Microsoft bought from Seattle Computer Products renaming it MS-DOS. Microsoft adapted it for the PC and licensed it to IBM. It was sold by IBM under the name of PC DOS. After learning about the deal, Digital Research founder Gary Kildall threatened to sue IBM for infringing DRI's intellectual property, and IBM agreed to offer CP/M-86 as an alternative operating system on the PC to settle the claim. Most of the BIOS drivers for CP/M-86 for the IBM PC were written by Andy Johnson-Laird.

The IBM PC was announced on 12 August 1981, and the first machines began shipping in October the same year, ahead of schedule. CP/M-86 was one of three operating systems available from IBM, with PC DOS and UCSD p-System.[5] Digital Research's adaptation of CP/M-86 for the IBM PC was released six months after PC DOS in spring 1982, and porting applications from CP/M-80 to either operating system was about equally difficult.[6] In November 1981, Digital Research also released a version for the proprietary IBM Displaywriter.[2][7]

On some dual-processor 8-bit/16-bit computers, special versions of CP/M-86 could natively run CP/M-86 and CP/M-80 applications.[8] A version for the DEC Rainbow was named CP/M-86/80, whereas the version for the CompuPro System 816 was named CP/M 8-16 (see also: MP/M 8-16).[9][10] The version of CP/M-86 for the 8085/8088-based Zenith Z-100 supported running programs for both processors as well.

When PC clones came about, Microsoft licensed MS-DOS to other companies as well. Experts found that the two operating systems were technically comparable, with CP/M-86 having better memory management but DOS being faster. BYTE speculated that Microsoft reserving multitasking for Xenix "appears to leave a big opening" for Concurrent CP/M-86.[11]

On the IBM PC, however, at US$240 per copy for IBM's version, CP/M-86 sold poorly compared to the US$40 PC DOS; one survey found that 96.3% of IBM PCs were ordered with DOS, compared to 3.4% with CP/M-86 or Concurrent CP/M-86.[12] In mid-1982 Lifeboat Associates, perhaps the largest CP/M software vendor, announced its support for DOS over CP/M-86 on the IBM PC.[13] BYTE warned that IBM, Microsoft, and Lifeboat's support for DOS "poses a serious threat to" CP/M-86,[5] and Jerry Pournelle stated in the magazine that "it is clear that Digital Research made some terrible mistakes in the marketing".[14]

By early 1983 DRI began selling CP/M-86 1.1 to end users for US$60.[12] Advertisements called CP/M-86 a "terrific value", with "instant access to the largest collection of applications software in existence … hundreds of proven, professional software programs for every business and education need"; it also included Graphics System Extension (GSX), formerly US$75.[15] The company began using distributors to sell CP/M-86 applications in retail stores.[16] In May 1983 DRI announced that it would offer DOS versions of all of its languages and utilities. It stated that "obviously, PC DOS has made great market penetration on the IBM PC; we have to admit that", but claimed that "the fact that CP/M-86 has not done as well as DRI had hoped has nothing to do with our decision".[17] By early 1984 DRI gave free copies of Concurrent CP/M-86 to those who purchased two CP/M-86 applications as a limited time offer, and advertisements stated that the applications were self-booting disks, which did not require loading CP/M-86 first.[18] In January 1984, DRI also announced Kanji CP/M-86, a Japanese version of CP/M-86, for nine Japanese companies including Mitsubishi Electric Corporation, Sanyo Electric Co. Ltd., Sord Computer Corp.[19][20][21] In December 1984 Fujitsu announced a number of FM-16-based machines using Kanji CP/M-86.[22][23]

CP/M-86 and DOS had very similar functionality, but were not compatible because the system calls for the same functions and program file formats were different, so two versions of the same software had to be produced and marketed to run under both operating systems. The command interface again had similar functionality but different syntax; where CP/M-86 (and CP/M) copied file SOURCE to TARGET with the command PIP TARGET=SOURCE, DOS used COPY SOURCE TARGET.

Initially MS-DOS and CP/M-86 also ran on computers not necessarily hardware-compatible with the IBM PC such as the Apricot and Sirius, the intention being that software would be independent of hardware by making standardised operating system calls to a version of the operating system custom tailored to the particular hardware. However, writers of software which required fast performance accessed the IBM PC hardware directly instead of going through the operating system, resulting in PC-specific software which performed better than other MS-DOS and CP/M-86 versions; for example, games would display fast by writing to video memory directly instead of suffering the delay of making a call to the operating system, which would then write to a hardware-dependent memory location. Non-PC-compatible computers were soon replaced by models with hardware which behaved identically to the PC's. A consequence of the universal adoption of detailed PC architecture was that no more than 640 kilobytes of memory were supported; early machines running MS-DOS and CP/M-86 did not suffer from this restriction, and some could make use of nearly one megabyte of RAM.

Reception

[edit]PC Magazine wrote that CP/M-86 "in several ways seems better fitted to the PC" than DOS; however, for those who did not plan to program in assembly language, because it cost six times more "CP/M seems a less compelling purchase". It stated that CP/M-86 was strong in areas where DOS was weak, and vice versa, and that the level of application support for each operating system would be most important, although CP/M-86's lack of a run-time version for applications was a weakness.[6]

Versions

[edit]A given version of CP/M-86 has two version numbers. One applies to the whole system and is usually displayed at startup; the other applies to the BDOS kernel. Versions known to exist include:

| OS | BDOS | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP/M-86 1.0 for AST[24] | 2.2? | 1981? | |

| CP/M-86 1.0 for the Altos ACS 16000/8600[24] | 2.2? | November 1981[25] | |

| CP/M-86 Version 1.1 for IBM Displaywriter | 2.2 | November 1981[2] | |

| CP/M-86 1.0 for the Sirius 1/Victor 9000 | 2.2a | 1981/1982 | |

| CompuView CP/M-86 | 2.x? | 1982 | 196 KB disk capacity, compatible with IBM PC hardware[6] |

| IBM CP/M-86 for the IBM Personal Computer Version 1.0 | 2.2 | 1982-04-05[6] | Initial release for the IBM PC. 141 KB disk capacity (Initial date defaults to 1982-02-10.)[6] |

| IBM CP/M-86 for the IBM Personal Computer Version 1.1 | 2.2 | March 1983 | Hard drive support was added. |

| CP/M-86 Plus Version 3.1 | 3.1 | October 1983 | Released for the Apricot PC. Based on the multitasking Concurrent CP/M-86 kernel, it could run up to four tasks at once. |

| Personal CP/M-86 Version 1.0 | 3.1 | November 1983 | Released for the Siemens PG685. |

| Personal CP/M-86 Version 3.1 | 3.3 | January 1985 | A version for the Apricot F-Series computers. This version gained the ability to use FAT formatted disks as used by DOS. |

| Personal CP/M-86 Version 2.0 | 4.1 | 1986 or later | Released for the Siemens PC16-20. This is the same BDOS used in DOS Plus 1.2. |

| Personal CP/M-86 Version 2.11 | 4.1 | 1986 or later | Released for the Siemens PG685. |

All known Personal CP/M-86 versions contain references to CP/M-86 Plus, suggesting that they are derived from the CP/M-86 Plus codebase.

A number of 16-bit CP/M-86 derivatives existed in the former East-bloc under the names SCP1700 (Single User Control Program), CP/K, and K8918-OS.[26] They were produced by the East-German VEB Robotron Dresden and Energiekombinat Berlin.[27][26]

Legacy

[edit]Caldera permitted the redistribution and modification of all original Digital Research files, including source code, related to the CP/M family through Tim Olmstead's "The Unofficial CP/M Web site" since 1997.[28][29][30] After Olmstead's death on 12 September 2001,[31] the free distribution license was refreshed and expanded by Lineo, who had meanwhile become the owner of those Digital Research assets, on 19 October 2001.[32][33][34][35]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The same filename extension .CMD is used by OS/2 and Windows for unrelated batch files.

References

[edit]- ^ "CP/M collection is back online with an Open Source licence". The Register. 2001-11-26.

- ^ a b c "Digital Research Has CP/M-86 for IBM Displaywriter" (PDF). Digital Research News – for Digital Research Users Everywhere. 1 (1). Pacific Grove, California, USA: Digital Research, Inc.: 2, 5, 7. November 1981. Fourth Quarter. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ Paterson, Tim (2007-09-30). "Design of DOS". DosMan Drivel. Archived from the original on 2013-01-20. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Swaine, Michael (2000) [1984]. Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer (2nd ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill. pp. 332–333. ISBN 0-07-135892-7.

- ^ a b Williams, Gregg (January 1982). "A Closer Look at the IBM Personal Computer". BYTE Magazine. 7 (1): 36–68. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- ^ a b c d e Edlin, Jim (1982-06-07). "CP/M Arrives – IBM releases a tailed-for-the-PC version of CP/M-86 that profits from the learning curve". PC Magazine: 43–46. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ Libes, Sol (December 1981). "Bytelines – News and speculation about personal computing". BYTE Magazine. 6 (12): 314–318. Retrieved 2015-01-29.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (March 1984). "New Machines, Networks, and Sundry Software – Chaos Manor is inundated with mew computers". BYTE Magazine. 9 (3): 46–54, 58–62, 68–76. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ Kildall, Gary Arlen (1982-09-16). "Running 8-bit software on dual-processor computers" (PDF). Electronic Design: 157. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ^ "OLDCOMPUTERS.COM Compupro 8/16". Archived from the original on 2016-01-03. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ^ Taylor, Roger; Lemmons, Phil (July 1982). "Upward Migration – Part 2: A Comparison of CP/M-86 and MS-DOS". BYTE Magazine. 7 (7): 330–338. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ a b "PC-Communiques: CP/M-86 Price Plunges to $60". PC Magazine: 56. February 1983. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ "The Microsoft/Lifeboat Battle Cry – Software firms back PC-DOS as 16-bit standard". PC Magazine: 159–162. June–July 1982. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (September 1983). "Eagles, Text Editors, New Compilers, and Much More". BYTE. p. 307. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ "CP/M gives you a new world of PC power … for a new low price". BYTE Magazine (advertisement). 8 (6): 65. June 1983. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

- ^ "Appendix II; Distribution strategies of selected software vendors" (PDF). The Rosen Electronics Letter. 1983-02-22. pp. 21–24. Retrieved 2025-06-05.

- ^ Hughes, George D. Jr. (July 1983). "The New View From Digital Research". PC Magazine: 403–406. Retrieved 2013-10-21.

- ^ Digital Research Inc. (February 1984). "Introducing software for the IBM PC with a $350 bonus!". BYTE Magazine (advertisement). 9 (2): 216–217. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ "International Report – Japan". Computerworld – The Newsweekly for the Computer Community. News. Vol. XVII, no. 2. Tokyo, Japan: CW Communications, Inc. 1984-01-09. p. 19. ISSN 0010-4841. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ "Kanji CPM-System von Digital Research Japan". Computerwoche (in German). Tokyo, Japan: IDG Business Media GmbH. 1984-01-13. Archived from the original on 2017-01-23. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L.; Lamb, John David; Buda, Janusz, eds. (2019) [1984-01-14]. "Digital Research Japan Develops Japanese Word-Processing Software For 16-Bit, 8-Bit Personal Computers; Features Grammatical Analysis Functions". Technical Japanese Translation. Vol. 1, no. 11. Waseda University. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2020-02-17.

- ^ "International Report – Japan". Computerworld – The Newsweekly for the Computer Community. News. Vol. XVII, no. 51. Tokyo, Japan: CW Communications, Inc. 1984-12-17. p. 22. ISSN 0010-4841. Archived from the original on 2020-02-17. Retrieved 2017-01-23.

- ^ Hiroshi, Hatta (2006-02-20). "Fujitsu FM16π (PAI)". IPSJ Computer Museum. Archived from the original on 2017-01-24. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- ^ a b Strutynski, Kathryn (2006-05-19). "Kathy Strutynski Early Years at Digital Research Incorporated" (Video). CHM Catalog Number 102762830. ITCHP 446f9931d5fa6. Lot X7847.2017. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2021-08-16 – via Computer History Museum. [8:23]; Bill Selmeier (ed.) 2006-05-24 (NB. About tasks, working relations, and stories from the very earliest years of Digital Research Incorporated.)

- ^ Garezt, Mark (1980-12-22). "According to Garetz..." InfoViews. InfoWorld – The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community. Vol. 2, no. 23. Palo Alto, California, USA: Popular Computing, Inc. p. 12. ISSN 0199-6649. Retrieved 2021-08-20.

- ^ a b Kurth, Rüdiger; Groß, Martin; Hunger, Henry (2019-01-03). "Betriebssystem SCP". www.robotrontechnik.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Kurth, Rüdiger; Groß, Martin; Hunger, Henry (2019-01-03). "Betriebssysteme". www.robotrontechnik.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Olmstead, Tim (1997-08-10). "CP/M Web site needs a host". Newsgroup: comp.os.cpm. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ Olmstead, Tim (1997-08-29). "ANNOUNCE: Caldera CP/M site is now up". Newsgroup: comp.os.cpm. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-09. [1]

- ^ "License Agreement". Caldera, Inc. 1997-08-28. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-09-09. [2][dead link] [3][permanent dead link]

- ^ "Tim Olmstead". 2001-09-12. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ Sparks, Bryan Wayne (2001-10-19). Chaudry, Gabriele "Gaby" (ed.). "License agreement for the CP/M material presented on this site". Lineo, Inc. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

[…] Let this email represent a right to use, distribute, modify, enhance and otherwise make available in a nonexclusive manner the CP/M technology as part of the "Unofficial CP/M Web Site" with its maintainers, developers and community. I further state that as Chairman and CEO of Lineo, Inc. that I have the right to do offer such a license. […] Bryan Sparks […]

- ^ Chaudry, Gabriele "Gaby" (ed.). "The Unofficial CP/M Web Site". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03.

- ^ Gasperson, Tina (2001-11-26). "CP/M collection is back online with an Open Source licence – Walk down memory lane". The Register. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01.

- ^ Swaine, Michael (2004-06-01). "CP/M and DRM". Dr. Dobb's Journal. 29 (6). CMP Media LLC: 71–73. #361. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-09. [4]

Further reading

[edit]- Dahmke, Mark (1984). The Byte Guide to CP/M-86. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-015072-0.

External links

[edit]- The Unofficial CP/M Website, which has a licence from the copyright holder to distribute original Digital Research software.

- The comp.os.cpm FAQ

- Intel iPDS-100 Using CP/M-Video