Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atari DOS

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

| Atari DOS | |

|---|---|

Atari DOS version 2.5, main menu | |

| Developer | Atari, Inc., Atari Corporation |

| Working state | Discontinued |

| Source model | Closed source |

| Initial release | 1979 |

| Latest release | XE 1.0 / 1987 |

| Available in | English |

| Supported platforms | Atari 8-bit computers |

| Default user interface | Menu |

| License | Proprietary EULA |

Atari DOS is the disk operating system used with the Atari 8-bit computers. Operating system extensions loaded into memory were required in order for an Atari computer to manage files stored on a disk drive. These extensions to the operating system added the disk handler and other file management features.

The most important extension is the disk handler. In Atari DOS 2.0, this was the File Management System (FMS), an implementation of a file system loaded from a floppy disk. This meant at least an additional 32 KB RAM was needed to run with DOS loaded.

Versions

[edit]There were several versions of Atari DOS available, with the first version released in 1979.[1] Atari was using a cross assembler with Data General AOS.

DOS 1.0

[edit]In the first version of DOS from Atari, all commands were only accessible from the menu. It was bundled with the Atari 810 disk drives. This version was entirely memory resident, which made it fast but occupied memory space.

DOS 2.0

[edit]- Also known as DISK OPERATING SYSTEM II VERSION 2.0S

The second, more popular version of DOS from Atari was bundled with the 810 disk drives and some early Atari 1050 disk drives. It is considered to be the lowest common denominator for Atari DOSes, as any Atari-compatible disk drive can read a disk formatted with DOS 2.0S.

DOS 2.0S consisted of DOS.SYS and DUP.SYS. DOS.SYS was loaded into memory, while DUP.SYS contained the disk utilities and was loaded only when the user exited to DOS.

In addition to bug fixes, DOS 2.0S featured improved NOTE/POINT support and the ability to automatically run an Atari executable file named AUTORUN.SYS. Since user memory was erased when DUP.SYS was loaded, an option to create a MEM.SAV file was added. This stored user memory in a temporary file (MEM.SAV) and restored it after DUP.SYS was unloaded. The previous menu option from DOS 1.0, N. DEFINE DEVICE, was replaced with N. CREATE MEM.SAV in DOS 2.0S.

Version 2.0S was for single-density disks, 2.0D was for double-density disks. 2.0D shipped with the 815 Dual Disk Drive, which was both expensive and incompatible with the standard 810, and thus sold only a small number; making DOS version 2.0D rare and unusual.

DOS 3

[edit]

The 1050 was the first drive from Atari to offer higher recording density. For reasons unknown, they did not take advantage of the 180 kB "double density" mode the hardware in the 1050 was capable of using, and instead introduced a new "Dual Density" mode. To avoid confusion, Atari users soon began referring to this as Enhanced Density to differentiate it from real double density systems.

Initially, this increased density mode was not able to be used as Atari shipped the drives with 2.0, which only supported the original 90 kB mode. This was addressed not long after with the release of DOS 3.0. When formatted with DOS 3.0, the disk held 40 tracks of 26 sectors, up from 18 on DOS 2.0. Each sector holds 128 bytes, for a total of 133,120 bytes of storage, up from DOS 2.0's 92,160.

In DOS 2.0, a 10-bit number was used to store sector numbers in the directory. This limited disks to a maximum of 1024 sectors. The new format had 1040 sectors, so 2.0 would not be able to use all of its capability. To address this, and to offer the possibility of working with even larger formats in the future, DOS 3.0 grouped sectors together in groups of eight, known as a block, each holding 1,024 bytes. The number in the directory was reduced to 8-bits, meaning it could address up 256 kB on a single disk. The boot information and directory used three blocks, leaving 130 kB free for user storage on the 1050.[2]

Unfortunately, the new directory format made the disks unreadable on DOS 2.0. The DOS 3.0 Master Diskette included a small utility program to copy a 2.0 disk to 3.0, but not one to copy it back. A separate utility allowed disks to be formatted in 2.0 format if compatibility was needed.[3] As a result of this decision, DOS 3 was extremely unpopular and did not gain widespread acceptance amongst the Atari user community.

DOS 3 provided built-in help via the Atari HELP key and/or the inverse key. Help files needed to be present on the system DOS disk to function properly. DOS 3 also used special XIO commands to control disc operations within BASIC programs.

DOS 2.5

[edit]- Also known as DISK OPERATING SYSTEM II VERSION 2.5

Version 2.5 is an upgrade to 3.0.[4] After listening to complaints by their customers, Atari released an improved version of their previous DOS. This allowed the use of Enhanced Density disks, and there was a utility to read DOS 3 disks. An additional option was added to the menu (P. FORMAT SINGLE) to format single-density disks. DOS 2.5 was shipped with 1050 disk drives and some early XF551 disk-drives.

Included utilities were DISKFIX.COM, COPY32.COM, SETUP.COM and RAMDISK.COM.

DOS 4.0

[edit]- Codename during production: QDOS

DOS 4.0 was designed for the 1450XLD. It was designed to operate with larger disk formats, adding double density and double sided support while also supporting the older single and enhanced density formats from DOS 2 and 2.5. To support the newer modes, it returned to the blocks concept used in DOS 3.0 when used to format enhanced or double density disks, but this time using slightly smaller 6-sector format, which held 768 bytes in enhanced density and 1536 bytes in double density.

Like DOS 3, disks formatted in the new higher-density formats were not compatible with older drives and DOSes. It could read and write to those disks to retain compatibility. However, it could not determine the format of a disk automatically, and the user had to select the format of the disks from the DOS menu.

The 1450XLD was never released, and the rights for DOS 4 were returned to the author, Michael Barall, who placed it in the public domain. It was published by Antic Software in 1984, and is sometimes referred to as "Antic DOS" for this reason.

DOS XE

[edit]- Codename during production: ADOS

DOS XE supported the double-density and double-sided capabilities of the Atari XF551 drive, as well as its burst I/O. DOS XE used a new disk format which was incompatible with DOS 2.0S and DOS 2.5, requiring a separate utility for reading older 2.0 files. It also required bank-switched RAM, so it did not run on the 400/800 machines. It supported date-stamping of files and sub-directories.

DOS XE was the last DOS made by Atari for the Atari 8-bit computers.

Third-party DOS programs

[edit]Many of these DOSes were released by manufacturers of third-party drives, anyone who made drive modifications, or anyone who was dissatisfied with the available DOSes. Often, these DOSes could read disks in higher densities, and could set the drive to read disks faster (using Warp Speed or Ultra-Speed techniques). Most of these DOSes (except SpartaDOS) were DOS 2.0 compatible.

SmartDOS

[edit]Menu driven DOS that was compatible with DOS 2.0. Among the first third-party DOS programs to support double-density drives.

Many enhancements including sector copying and verifying, speed checking, turning on/off file verifying and drive reconfiguration.

Published by Rana Systems. Written by John Chenoweth and Ron Bieber, last version 8.2D.

OS/A+ and DOS XL

[edit]DOS produced by Optimized Systems Software. Compatible with DOS 2.0 - Allowed the use of Double Density floppies. Unlike most ATARI DOSses, this used a command line instead of a menu. DOS XL provided a menu program in addition to the command line.

SuperDOS

[edit]This DOS could read SS/SD, SS/ED, SS/DD and DS/DD disks, and made use of all known methods of speeding up disk-reads supported by the various third-party drive manufacturers.

Published by Technical Support[clarification needed]. Written by Paul Nicholls.

Top-DOS

[edit]Menu driven DOS with enhanced features. Sorts disk directory listings and can set display options. File directory can be compressed. Can display deleted files and undelete them. Some advanced features required a proprietary TOP-DOS format.

Published by Eclipse Software. Written by R. K. Bennett.

Turbo-DOS

[edit]This DOS supports Turbo 1050, Happy, Speedy, XF551 and US Doubler highspeed drives. XL/XE only.

Published by Martin Reitershan Computertechnik. Written by Herbert Barth and Frank Bruchhäuser.

MyDOS

[edit]This DOS adds the ability to use sub-directories, and supports hard-drives.[5][6][7][8]

Published by Wordmark Systems, includes complete source code under copyleft license, with an exception on distributing commercially only if it included in software or derived software made of it would cost less than $50.[9][10][11][12]

There is number of free addons and extensions for MyDOS created by users.[13][14][15][16]

MyPicoDOS

[edit]This is a fork of MyDOS, intended to be used as game laucher.[17]

SpartaDOS

[edit]This DOS used a command-line interface. It was not compatible with DOS 2.0, but could read DOS 2.0 disks. It supports subdirectories and hard drives and is capable of handling filesystems sized up to 16 MB. Included the capability to create primitive batch files.

SpartaDOS X

[edit]

A more sophisticated version of SpartaDOS, which strongly resembles MS-DOS in its look and feel. It was shipped on a 64 KB ROM cartridge.

RealDOS

[edit]A SpartaDOS compatible DOS (in fact, a renamed version of SpartaDOS 3.x, for legal reasons).

RealDOS is shareware by Stephen J. Carden and Ken Ames.

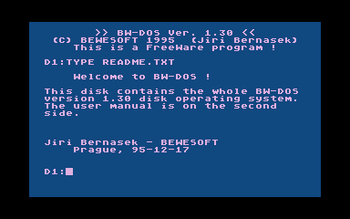

BW-DOS

[edit]

A SpartaDOS compatible DOS. It has a much lower memory footprint compared to the original SpartaDOS and does not use the RAM under the ROM of XL/XE machines, allowing it to be used on the older Atari 400/800 models.

BW-DOS is freeware by Jiří Bernasek. The last version 1.30 was released in December 1995.

Since then, Holger Janz has worked with Jiří Bernasek to release BW-DOS 1.4, and in January 2025, BW-DOS 1.5 was released.

XDOS

[edit]XDOS is freeware by Stefan Dorndorf.

LiteDOS

[edit]Minimalistic DOS for Atari, supporting files formats of various other DOS software, such as files of Atari DOS and MyDOS.[18]

Disk formats

[edit]A number of different formats existed for Atari disks.[8] Atari DOS 2.0S, single-sided, single-density disk had 720 sectors divided into 40 tracks. After formatting, 707 sectors were free. Each 128-byte sector used the last 3 bytes for housekeeping data (bytes used, file number, next sector), leaving 125 bytes for data. This meant each disk held 707 × 125 = 88,375 bytes of user data.

The single-density disk holding a mere 88 KB per side remained the most popular Atari 8-bit disk format throughout the series' lifetime, and almost all commercial software continued to be sold in that format (or variants of it modified for copy protection), since it was compatible with all Atari-made disk drives.

- Single-Sided, Single-Density: 40 tracks with 18 sectors per track, 128 bytes per sector. 720 sectors, 90 KB capacity.

- Single-Sided, Enhanced-Density: 40 tracks with 26 sectors per track, 128 bytes per sector. 1040 sectors, 130 KB capacity. Readable by the 1050 and the XF551.

- Single-Sided, Double-Density: 40 tracks with 18 sectors per track, 256 bytes per sector. 720 sectors, 180 KB capacity. Readable by the XF551, the 815, or modified/upgraded 1050.

- Double-Sided, Double-Density: 80 tracks (40 tracks per side) with 18 sectors per track, 256 bytes per sector. 1440 sectors (720 sectors per side), 360 KB capacity. Readable by the XF551 only.

Percom standard

[edit]In 1978, Percom established a double-density layout standard which all other manufacturers of Atari-compatible disk drives such as Indus, Amdek, and Rana —except Atari itself— followed. A configuration block of 12 bytes defines the disk layout.[11][19][20]

RAMCART

[edit]It is ramdisk for Atari XL, compatible with many DOS software.[21]

IDE Plus 2.0

[edit]It is a utility to work with Atari disks and diskettes, based on MyDOS and SpartaDOS.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Atari Archived February 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wilkinson 1982, p. 23.

- ^ Wilkinson 1982, p. 25.

- ^ Chadwick, Ian (1985). "Appendix Seventeen: Dos 2.5 And The 1050 Drive". Mapping the Atari. Greensboro, North Carolina: Compute! Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87455-004-1.

- ^ Marslett, Charles; Puff, Robert (1988). MYDOS Version 4.50 (PDF) (User Guide). WORDMARK Systems.

For Atari Home Computers.

- ^ Miscellaneous PD Disks: MyDos Disk Operating System Replacement, utilities, retrieved 2024-09-14

- ^ "Atari 400 800 XL XE MyDOS 5.0". www.atarimania.com. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ a b Fox-1, Sysop. "Disk Formats Explained". THUNDERDOME – the ATARI site. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

There is no real important difference in the special boot bytes on a MyDos disk and an Atari Dos Disk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "MyDOS programs and tools". www.wordmark.org. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ "Mathy's MyDOS page". www.mathyvannisselroy.nl. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ a b "ANTIC The Atari 8-bit Podcast: ANTIC Interview 393 - Charles Marslett, MYDOS and FastChip". ataripodcast.libsyn.com. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

Charles Marslett wrote floppy disk and hard drive drivers for Percom, and was the creator of MYDOS, a disk operating system for the Atari 8-bit computers that offered support for double density sectors, subdirectories, and hard drives.

- ^ "Index of /~archive/atari/8bit/Dos/Mydos". websites.umich.edu. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ Fox-1, Sysop (2018-06-05). "Tag: mydos". THUNDERDOME – the ATARI site. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Atari 400/800/XL/XE Miscellaneous Software & Utilities - Chebucto Community Net". www.chebucto.ns.ca. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ "MyDOS". SourceForge. 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ a b ":: drac030.atari8.info". drac030.krap.pl. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

Utility disk for the interface. ATR format, side A for MyDOS, side B for SpartaDOS (updated 19 I 2011).

- ^ Reichl, Matthias (2024-03-27), HiassofT/MyPicoDOS, retrieved 2024-09-14

- ^ "LiteDOS (c) Mr.Atari". www.mr-atari.com. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ Wilkinson, Bill (October 1985). "Atari Disk Drive Compatibility". Compute!. pp. 110–111. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Kay Savetz (2020-08-16), Charles Marslett, MYDOS and FastChip — interview, retrieved 2024-09-14

- ^ Janz, Holger (2024-05-27), HolgerJanz/RAMCART, retrieved 2024-09-14

- Notes

- Wilkinson, Bill (1982), Inside Atari DOS, Compute! Books, ISBN 978-0-942386-02-8 (Online version)

- Mapping the Atari, Revised Edition by Ian Chadwick

External links

[edit]- Atari DOS Reference Manual Archived 2011-05-15 at the Wayback Machine — Reference manual for DOS 3.

- Antic Vol.4 No.3 Everything You Wanted To Know About Every DOS

- Atari Dos 4 (aka ANTIC Dos aka QDOS) Documentation on Atari DOS 4

- MyDOS Source Code from Wordmark Systems.

Atari DOS

View on GrokipediaOverview

Historical Context

The development of Atari DOS originated in late 1978 when Atari contracted Shepardson Microsystems, Inc., to create a file management system alongside Atari BASIC for the upcoming Atari 400 and 800 computers, as well as the Atari 810 disk drive.[5] Shepardson, led by project manager Paul Laughton—who had previously authored Apple DOS—delivered a functional version of the File Management System (FMS), commonly known as Atari DOS, by December 1978, just ahead of the January 1979 Consumer Electronics Show where the hardware debuted.[5] This effort was driven by Atari's need for reliable disk-based storage to complement the new 8-bit family, marking a shift from earlier prototypes that relied on less efficient media.[6] Atari DOS 1.0 was released in late 1979 specifically to enable floppy disk operations on the Atari 8-bit computers, providing essential support for loading, saving, and managing files via the 810 drive.[7] As the first official disk operating system for the platform, it integrated directly with the Atari operating system to handle peripheral interactions, allowing users to transition from slower cassette tapes to faster disk storage for programs and data.[5] The evolution of Atari DOS was closely tied to hardware advancements, such as the introduction of the Atari 1050 disk drive in June 1983, which supported enhanced-density formatting and necessitated updates to maximize storage capacity. This led to the development of DOS 3 in 1983 for dual-density support on the 1050. Due to compatibility issues with DOS 3, it was replaced by the more reliable DOS 2.5 in late 1984, developed by Optimized Systems Software, which also supported dual density while maintaining compatibility with earlier single-density drives like the 810.[3][8] Such iterations reflected Atari's ongoing efforts to improve data throughput and capacity in response to advancing peripheral technology.[9] A key milestone in Atari DOS was its integration with Atari's Serial Input/Output (SIO) bus, a proprietary interface designed for daisy-chaining peripherals like disk drives, printers, and modems directly to the computer.[10] This SIO component within DOS managed communication protocols, enabling efficient device control without additional hardware.[11] Overall, Atari DOS played a pivotal role in enabling software distribution and data storage for early Atari users by replacing cumbersome cassette-based systems with more reliable and faster floppy disk alternatives, facilitating broader adoption of the 8-bit ecosystem.[5]Core Architecture and Features

Atari DOS employs a modular architecture centered on the File Management System (FMS), which serves as the core disk handler, integrated with the Central Input/Output (CIO) routines of the Atari 8-bit operating system. The Disk Utility Package (DUP), a separate module loaded into RAM, provides the user interface for system commands, such as displaying a menu upon invocation via the "DOS" command in BASIC, and translates user inputs into CIO calls to access FMS functions like file operations. This separation allows DUP to be replaced or customized without altering the underlying FMS, while CIO acts as the intermediary, managing up to eight Input/Output Control Blocks (IOCBs) for device-independent I/O requests over the Serial Input/Output (SIO) bus, enabling efficient communication with peripherals like disk drives specified as "D:" devices. Later versions introduced variations in the FMS structure.[10][12] In early versions, such as DOS 2.5, the file system organizes data into fixed-size sectors, supporting single-density formats with 720 sectors of 128 bytes each on standard 5.25-inch disks, and double-density formats with up to 1040 sectors of the same size on compatible drives like the Atari 1050, achieved by emulating paired sector reads for effective 256-byte transfers. Directory management relies on the Volume Table of Contents (VTOC), located in sector 360, which uses a bitmap to track up to 707 available data sectors per disk, excluding reserved areas for boot code, the VTOC itself, and the directory entries in sectors 361-368; this structure supports up to 64 files per directory, each identified by an 8-character name and 3-character extension. Later versions, such as DOS XE, introduced changes like native 256-byte sectors and larger disk support up to 16 MiB.[13][14] Key features include basic commands for disk maintenance—such as copying files between drives, deleting or renaming entries, formatting new disks, and listing directory contents—executed through DUP's menu-driven interface, with FMS handling the underlying sector allocation and data transfer via burst-mode SIO operations for efficiency. Early versions lack subdirectories, limiting organization to flat file lists, and the system is implemented in 6502 assembly language to operate within the constraints of 48 KB RAM systems, prioritizing low memory footprint over advanced features.[10][13] Error handling is managed through status codes returned via CIO OS calls, with the IOCB status byte (ICSTA) indicating success ($01) or specific failures like file not found ($AA) or device timeout ($8A), allowing applications to query and respond to issues during file access or SIO transactions without halting the system.[12]Official Versions

DOS 1.0

Atari DOS 1.0, the initial version of the disk operating system for Atari 8-bit computers, was released in September 1979 by Atari Corporation to accompany the launch of the Atari 400 and 800 computers along with the Atari 810 5.25-inch floppy disk drive.[3] Developed by Paul Laughton at Shepardson Microsystems, it consisted of a File Management Subsystem (FMS) and a Disk Utility Package (DUP), designed specifically for the hardware constraints of the era.[3] This version provided essential disk management capabilities tailored to the Atari 810's single-sided, single-density format, which utilized FM encoding and offered a formatted capacity of approximately 90 KB per disk (precisely 88,625 bytes across 709 data sectors of 125 bytes each after accounting for 11 special sectors).[3][15] The system featured a menu-driven interface accessed via the DUP, supporting basic operations such as formatting disks (FORMAT), copying files (COPY), retrieving files from cassette to disk (GET), placing files from disk to cassette (PUT), and displaying disk contents (DIRECTORY).[3] Notably absent were advanced functions like file renaming or protection (lock/unlock), limiting users to fundamental file handling without finer control over attributes.[3] Architecturally, DOS 1.0 operated as a binary-loadable program that booted from the disk inserted in drive 1 (D1:), loading into RAM and integrating with the Atari Operating System's Serial Input/Output (SIO) handler for all disk communications across up to four drives (D1: to D4:).[3] It supported a maximum of 64 files per disk via an 8-sector file directory and used 128-byte sectors organized in 40 tracks with 18 sectors per track, though only single-density disks were compatible.[3] Performance was constrained by the era's hardware, with operations like file copying relying on small buffers that required frequent menu redisplay for subsequent commands, resulting in slow sector-by-sector access over the SIO bus at a typical transfer rate of 6 kbps.[3] This approach, while reliable for basic tasks, made large file transfers cumbersome and highlighted the system's rudimentary design. Additionally, DOS 1.0's exclusive support for single-density FM-encoded disks rendered it incompatible with later double-density drives and formats, preventing use with enhanced storage media introduced subsequently.[3][15] Primarily intended for systems with at least 48 KB of RAM—such as fully expanded Atari 400 or 800 models—DOS 1.0 facilitated loading and saving Atari BASIC programs as well as simple data files, enabling early users to transition from cassette-based storage to more efficient disk workflows.[3] Its binary file format was unique to this version, ensuring seamless operation within its ecosystem but requiring conversion for compatibility with future DOS iterations.[3] Overall, DOS 1.0 laid the groundwork for disk-based computing on Atari platforms, emphasizing simplicity and integration with the SIO interface for reliable, if limited, peripheral management.[3]DOS 2.0

Atari DOS 2.0, also known as DOS II or DOS 2.0S in its single-density variant, was released in 1980 as an interim update to the initial DOS 1.0, serving as a bridge before the introduction of the Atari 1050 disk drive in 1983.[16][2] This version built upon the basic file management system of its predecessor by introducing new commands to enhance usability, including RENAME for changing file names (e.g., converting "TEMPDAT" to "NAMESDAT" using wildcards) and PROTECT for locking files against modifications, which appear marked with an asterisk in the directory listing.[17][2] These additions addressed limitations in file handling from DOS 1.0, allowing users greater control over disk contents without needing external programs.[17] Disk capacity remained constrained to 90 KB in single-density mode, utilizing 707 sectors of 128 bytes each for a total of approximately 88,375 usable bytes after reserving space for the volume table of contents (VTOC) and boot sectors.[17] To improve reliability, DOS 2.0 incorporated better error recovery mechanisms, such as diagnostic steps for boot failures (e.g., handling wrong diskette insertions or bad sectors by prompting for reformatting or file recovery via sector-by-sector access).[17][2] Distribution occurred via a master floppy diskette bundled with Atari BASIC cartridges, ensuring broad availability for Atari 400 and 800 users.[17] The boot process relied on a special loader that initiated from the disk in Drive 1 upon powering on the system, followed by typing "DOS" in BASIC to load the DUP.SYS utility file into memory for menu access.[17] Key enhancements centered on the Disk Utility Package (DUP) menu, which provided an interactive interface for operations like binary load/save, memory image preservation via MEM.SAV, and disk initialization in extended format (XF) to optimize single-density media.[17] This menu-driven approach improved user interaction over DOS 1.0's more rudimentary setup, offering options such as directory display, file copying, and deletion with confirmation prompts to prevent accidental data loss.[16][17] However, the absence of double-density support limited its longevity, rendering it quickly obsolete as hardware like the 1050 drive enabled higher capacities, prompting the need for subsequent versions by 1983.[16][2]DOS 2.5

DOS 2.5, released by Atari Corporation in 1984, was specifically optimized for the Atari 1050 disk drive introduced the previous year, introducing enhanced density support that utilized modified frequency modulation (MFM) encoding to achieve approximately 130 KB of formatted storage per disk—roughly 43% more than the 90 KB single-density limit of prior versions.[16] This dual-mode capability allowed the system to operate in either single-density mode for compatibility with older 810 drives or enhanced density on the 1050, where it formatted disks with 26 sectors per track (each 128 bytes) for a total of 1040 sectors, with approximately 1010 usable after overhead, leaving 707 sectors accessible to DOS 2.0 systems while reserving the rest for higher-capacity use.[9] The enhanced density leveraged the 1050's ability to switch between group code recording (GCR) on outer tracks and MFM on inner tracks, enabling denser data packing without requiring full double-density hardware.[16] Key enhancements included the DUPLICATE disk command (menu option J), which facilitated complete disk-to-disk copying by reading all sectors sequentially and optionally formatting the target disk in advance to prevent errors during the process.[16] File management explicitly supported standard Atari types such as .COM for directly executable binary files, .EXE for load-and-go relocatable programs, and generic data files, with directory listings displaying contents from the additional sectors (beyond sector 707) enclosed in angle brackets to indicate their inaccessibility to single-density systems.[9] The Volume Table of Contents (VTOC) was extended to accommodate the increased sector count, relocating auxiliary bitmap information to sector 1024 to map sectors 720 through 1023, thereby supporting up to 720 sectors in legacy mode while fully utilizing the 1050's capacity.[14] DOS 2.5 maintained full backward compatibility with DOS 2.0-formatted disks, allowing seamless reading and writing in single-density mode via a dedicated menu option (P) for formatting, which ensured interoperability across Atari 8-bit systems. It quickly became the de facto standard for most commercial software distributed on Atari 8-bit computers during the 1980s, as the 1050 drive dominated the market and many titles were mastered in enhanced density to maximize storage efficiency.[3] However, users occasionally reported compatibility challenges with non-standard third-party drives that failed to properly handle the 1050's density-switching mechanism, leading to read/write errors on enhanced-density media.[16]DOS 3.0

Atari DOS 3.0, released in 1983, was developed internally by Atari engineers, led by Richard K. Nordin, primarily to support the enhanced-density capabilities of the Atari 1050 disk drive and the built-in double-sided drive of the rare Atari 1450XLD computer.[18][16] It enabled approximately 50% more storage per diskette compared to the single-density format of earlier DOS versions, achieving up to 130 KB on single-sided enhanced-density disks using 26 sectors of 128 bytes per track.[18][19] For the 1450XLD's double-sided drive, DOS 3.0 treated each side as a separate virtual single-sided drive (appearing as two independent 1050-like units), allowing effective use of both sides but without seamless double-sided file management, resulting in capacities up to around 260 KB per disk.[3][20] Key additions in DOS 3.0 included native support for enhanced-density formatting, which utilized modified MFM encoding to increase sector count while maintaining compatibility with the Atari 8-bit family's disk controller.[16][18] It also introduced a one-way file conversion utility to migrate data from DOS 2.0/2.0S formats to the new structure, addressing the incompatibility between enhanced-density media and prior single-density disks.[19][18] The system retained core double-density basics from experimental modes in earlier drives but optimized them for standard operation on the 1050, without requiring custom drive firmware hacks.[16] The command set expanded on the menu-driven interface of DOS 2, with options for file indexing (displaying directories with more detailed listings including file sizes and protection status), disk initialization, duplication, and wildcard-based operations for copying, renaming, erasing, and protecting files (e.g., using * and ? patterns).[18] It improved handling of write-protected media by enforcing checks during formatting and duplication to prevent accidental overwrites, and included a help system via accessory files for user guidance.[18] These enhancements made routine disk management more robust for higher-capacity media, though the interface remained BASIC-loaded and memory-resident like its predecessors.[16] DOS 3.0 was distributed on the "Master Diskette 3" (part number DX5052) and bundled with 1050 drives from 1983 to 1985, but saw limited adoption due to the 1450XLD's troubled release—only a small number of units were produced before the XL line's production issues in 1983.[21][19] The drive's late availability and the subsequent introduction of more compatible DOS versions further restricted its rollout.[16] Despite its innovations, DOS 3.0 had notable limitations, including inefficient cluster allocation (grouping files in large 1 KB blocks, leading to wasted space on smaller disks) and lack of backward compatibility with DOS 2.0 without conversion, which deterred widespread use.[22][16] It overlapped significantly with the more versatile DOS 2.5 (released in 1984), which supported similar densities while maintaining better compatibility, resulting in DOS 3.0 being rarely used outside initial 1050 setups and causing some software to exhibit incompatibility due to format differences.[19][3]DOS 4.0

Atari DOS 4.0, also known as QDOS or Antic DOS, was developed by Michael Barall in 1983–1984 as a next-generation operating system intended for the unreleased Atari 1450XLD computer. Following the sale of Atari's consumer division to Jack Tramiel in July 1984, the rights reverted to Barall, who placed it in the public domain and licensed it to Antic Software for publication later that year.[23] This RAM-resident system represented an update over prior versions like DOS 3.0 by emphasizing faster operation through efficient memory usage and enhanced drive management, loading entirely into RAM upon boot to minimize disk access delays. Following the 1984 sale of Atari's consumer division, DOS 4.0 was placed in the public domain and distributed by Antic Software, rather than as an official Atari product.[24] Key features included relocatable code optimized for systems with 64 KB or more of RAM, allowing flexible placement in memory, and support for concurrent access to multiple drives, with configuration for up to eight physical drives (numbered 1–8) and ten logical drives (D0: to D9:).[24] It maintained backward compatibility with earlier Atari DOS formats while extending support to disks up to 360 KB in capacity, including single-sided/single-density (90 KB), single-sided/enhanced-density (130 KB), single-sided/double-density (180 KB), and double-sided/double-density configurations.[25] Additional capabilities encompassed binary load diagnostics via its Disk Utility Package and memory buffering mechanisms that reduced I/O overhead by allocating 2–16 buffers of 128 or 256 bytes each for data handling.[24] As a standard for many mid-1980s Atari 8-bit applications, DOS 4.0 offered advantages in speed and multi-drive operations, making it suitable for users with expanded storage setups, though it required sufficient RAM and compatible hardware like the Atari 810 or 1050 drives.[23] However, it lacked native subdirectory support, limiting file organization to flat directories with a maximum of 128 entries, and relied on disk-based distribution rather than integrated cartridge hardware, necessitating a boot from formatted media.[23]DOS XE

DOS XE, released in January 1988 by Atari Corporation, served as the final official disk operating system for the Atari 8-bit family, tailored primarily for the XE series computers such as the 130XE and bundled with the XF551 double-density disk drive.[6] Developed to leverage the advanced hardware of the late 1980s Atari lineup, it loaded from disk as the DOSXE.SYS file and required at least 64 KB of RAM, though it fully supported the 128 KB expansions available in models like the 130XE by utilizing the extra memory as a RAM disk with up to 251 usable 256-byte sectors for rapid file access.[26] This RAM disk functionality allowed users to designate the expanded memory as a high-speed virtual drive, enhancing performance for temporary storage and operations on XE systems.[27] Optimized for the Parallel Bus Interface (PBI) present on XE models and the XF551 drive, DOS XE enabled faster data transfer rates and supported up to four daisy-chained disk drives, including compatibility with earlier models like the Atari 810 and 1050.[26] Key features included subdirectory support for organizing up to 1,250 files per directory, batch file execution for automated command sequences, and wildcard operations for efficient file management, all while maintaining backward compatibility with prior disk formats through built-in utilities—though it introduced a new enhanced format for XF551 media that required conversion for full interoperability with DOS 2.0 and 2.5 disks.[27] Additionally, it provided improved error logging via detailed status commands and an appendix of over 250 error codes with troubleshooting guidance, aiding users in diagnosing issues like hardware failures or file corruption.[26] Distributed exclusively with new XE systems and XF551 drives through 1992, DOS XE marked the end of Atari's official DOS development amid the company's strategic pivot toward the Atari ST line and declining 8-bit market share.[6] Its adoption remained limited, as many users stuck with established versions like DOS 2.5 due to the XF551's niche availability and the broader industry shift away from Atari's 8-bit ecosystem.[28] Despite these constraints, DOS XE represented a refined culmination of Atari's file management innovations, emphasizing hardware integration over radical redesign.[27]Third-Party Implementations

MyDOS and Variants

MyDOS, a prominent third-party disk operating system for Atari 8-bit computers, was developed by Charles Marslett of Wordmark Systems and first released in August 1983 as version 3.07, serving as a faster alternative to Atari DOS 2.5 with optimized disk I/O operations that reduced access times compared to the official system.[29][30] Among its core features, MyDOS introduced subdirectories for hierarchical file organization, volume names stored in the Volume Table of Contents (VTOC) to label and distinguish disks, and file locking via Central Input/Output (CIO) calls to protect files from unintended changes or deletion. It also extended storage support to up to 1MB disks through custom sectoring formats that allowed denser packing while maintaining compatibility with standard Atari hardware. A specialized variant, MyPicoDOS, emerged in 1992 as a compact implementation tailored for embedded applications in games and demonstrations, offering stripped-down functionality like basic file loading to minimize memory usage and enable seamless integration into resource-constrained software.[31] MyDOS provided advantages through its intuitive menu-driven interface, which mirrored the familiar structure of Atari DOS 2.5 for easy adoption, and full binary compatibility with Atari DOS file formats, allowing direct reading and execution of existing programs without conversion.[30] Its popularity grew significantly among Atari enthusiasts, particularly for shareware and utility distributions, as later versions like 4.53 were released as freeware in the early 1990s, facilitating free sharing and widespread integration into community software projects.[29]SpartaDOS and Derivatives

SpartaDOS was developed by ICD, Inc. as a command-line oriented disk operating system for Atari 8-bit computers, with its first version, SpartaDOS 1.1, released in 1984 to provide greater efficiency over Atari's official DOS implementations.[32] Designed to occupy just 8 KB of memory in its core configuration, it introduced advanced features such as batch file support for scripting sequences of commands and wildcard matching for file operations, enabling more flexible file management. These capabilities made it particularly appealing for power users seeking a MS-DOS-like experience on the Atari platform.[33] A defining characteristic of SpartaDOS was its support for hierarchical directories, allowing nested subdirectories limited only by available disk space, which contrasted with the flat file structure of earlier Atari DOS versions. Filenames followed an 8.3 convention (up to eight characters for the name and three for the extension), with full compatibility for Atari's XIO commands to interface with peripherals such as printers and modems.[34] This structure facilitated efficient organization and access, influencing subsequent Atari software development by promoting scripted automation and modular programming practices.[32] In 1987, ICD released SpartaDOS X (version 4.0) as a cartridge-based upgrade, expanding the core to 16 KB while incorporating a 48 KB ROM-disk for utilities and a configurable RAM disk feature that utilized expanded memory for high-speed temporary storage.[33] It maintained backward compatibility with disk-based SpartaDOS versions but added enhanced device handling, including support for network interfaces like the ICD Black Box for file transfer over Ethernet.[32] SpartaDOS X's command processor and scripting depth solidified its popularity among advanced users for tasks requiring precise control and automation, with updates continuing into the 2020s (e.g., version 4.49).[34] RealDOS, first released in 2012 as a derivative of SpartaDOS, was designed to emulate its command-line interface and file system while extending compatibility to modern hardware interfaces such as IDE hard drives and SCSI controllers.[35] This adaptation allowed legacy SpartaDOS software to run on upgraded Atari systems without modification, preserving the ecosystem for preservation efforts and hobbyist applications into the present day, with active maintenance as of 2024.Other Third-Party DOS Systems

In addition to the more prominent third-party DOS implementations, several lesser-known systems emerged in the 1980s, targeting specific performance enhancements, compatibility improvements, or resource constraints on Atari 8-bit computers. These programs often built upon the core structure of Atari DOS 2.0 while introducing niche optimizations, such as faster disk access or reduced memory footprints, to address limitations in hardware like the 1050 floppy drive or systems with limited RAM. Many were distributed as disk-based utilities or cartridges, reflecting the era's focus on practical hacks for hobbyists and developers. SmartDOS, released in 1984 by Rana Systems and developed by John Chenoweth and Ron Bieber, was a menu-driven operating system fully compatible with Atari DOS 2.0. It was among the earliest third-party DOS variants to support double-density drives, including the Atari 1050, through features like sector copying, verification, speed testing, and drive reconfiguration for improved performance. These optimizations enabled turbo modes that accelerated data transfer rates on compatible hardware, making it particularly useful for users seeking quicker file operations without extensive hardware modifications.[36] OS/A+ and its successor DOS XL, both from Optimized Systems Software (OSS) and released around 1983, functioned as multi-OS loaders with advanced memory management capabilities for Atari 8-bit systems equipped with floppy drives. OS/A+, a command-line DOS available as a cartridge, allowed seamless switching between different operating environments while maintaining compatibility with Atari DOS file structures. DOS XL expanded this with single- and double-density support, enhanced file handling up to larger sizes, and integrated utilities like a debugger (BUG/65), optimizing RAM usage for multitasking and reducing overhead in memory-constrained setups. These systems prioritized broad OS interoperability, enabling users to boot alternative environments directly from disk without rebooting the hardware.[37][38] In the mid-1980s, several speed-focused DOS variants appeared, including SuperDOS, Top-DOS, and Turbo-DOS, which emphasized RAM buffering to boost disk I/O efficiency on standard Atari drives. SuperDOS, developed by Australian programmer Paul Nicholls and copyrighted from 1986 to 1988 (with versions 2.9, 5.0, and 5.1), offered Atari DOS 2.0 compatibility alongside flexible RAMdisk support for the Atari 130XE, handling single-, enhanced-, and double-density formats up to 180K per disk for faster access times. Top-DOS, from Eclipse Software, evolved from a simple modification of Atari DOS 2.0 into a commercial product with enhanced buffering for rapid file transfers and directory management, appealing to users needing quick program loading in resource-limited environments. Turbo-DOS similarly utilized RAM caching to accelerate operations, supporting tape and disk media while providing menu-based utilities for verification and duplication, often bundled for mid-range Atari setups. These systems shared a common theme of performance hacks, leveraging available memory to minimize wait times during common tasks like loading BASIC programs.[39][40][2] By the mid-1990s, compact DOS implementations like BW-DOS catered to low-RAM or specialized hardware configurations, often as lightweight alternatives for older Atari models. BW-DOS, version 1.30 released in 1995 but rooted in early-1990s development, required only 48KB RAM and set MEMLO at $1EE4 to preserve space for software like Turbo-BASIC, while supporting up to five open files, multiple drives, and RAMdisks including XLRDISK (using 14KB under the OS-ROM on all XL/XE machines). Later systems like XDOS (initially released around 2009 by Stefan Dorndorf) and LiteDOS (developed in the 2010s with updates as recent as 2022) focused on minimalism with subdirectory support inspired by more advanced systems, enabling efficient file organization on drives with limited sectors while maintaining broad compatibility; LiteDOS uses just 2KB RAM, freeing up to 8KB more memory on 64KB XL/XE systems (especially with Turbo-BASIC), providing essential functions like booting and basic file management in seconds for low-resource or embedded applications. These later systems highlighted compatibility hacks for aging hardware, frequently distributed as cartridges or small disk images to extend the usability of Atari 8-bit platforms, and many are now available as freeware for preservation and emulator use.[41][42][43]Storage Management

Disk Formats and Standards

Atari DOS utilized several standard disk formats tailored to the capabilities of compatible 5.25-inch floppy drives, primarily employing frequency modulation (FM) for single-density and modified frequency modulation (MFM) for higher densities to increase storage efficiency.[44] The single-density format, common with the Atari 810 drive, provided 90 KB capacity using FM encoding across 40 tracks with 18 sectors per track, each sector holding 128 bytes.[45][44] Double-density formats provide 180 KB single-sided capacity using MFM encoding with 40 tracks and 18 sectors per track of 256 bytes each, while enhanced-density formats offer 130 KB single-sided with 40 tracks and 26 sectors of 128 bytes. Double-sided double-density reaches 360 KB using 80 effective tracks.[44] Sector layouts varied by density to accommodate encoding differences and drive hardware. In single-density mode, each of the 40 tracks contained 18 sectors of 128 bytes, resulting in 720 total sectors numbered from 1 to 720, with the first three reserved for boot records.[45] Enhanced-density implementations used 26 sectors per track with 128 bytes per sector for compatibility, yielding 1,040 sectors and supporting the increased bit rate of MFM without altering the logical sector size. Double-density uses 18 sectors per track with 256 bytes per sector, yielding 720 sectors.[44] The Volume Table of Contents (VTOC), located in sector 360 for single-density disks, managed allocation via a 90-byte bitmap starting at offset 10, where each bit represented one sector's status (0 for allocated, 1 for free), covering sectors 0 through 719 despite sector 0 being unused for compatibility.[45] Drive parameters, including density, number of sides, tracks, sectors per track, and bytes per sector, were standardized in the 12-byte Percom Block, a configuration structure queryable via the Serial Input/Output (SIO) interface using the "N" command to read and "O" to write.[46] Byte 0 specified tracks (e.g., 40 decimal), bytes 2-3 held sectors per track as a 16-bit value, byte 4 indicated sides (0 for single, 1 for double), byte 5 denoted density (0 for FM/single, 4 for MFM/double), and bytes 6-7 provided bytes per sector.[46] This block ensured interoperability across drives like the Atari 1050 and XF551, which supported Percom for dynamic geometry detection.[46] Disk initialization occurred through DOS commands such as FORMAT in DOS 2.0, which cleared tracks, wrote sector headers, zeroed data areas, and initialized the VTOC bitmap and directory, or XFREE in later versions like DOS 2.5 for extended formatting options.[45] These processes set the disk geometry according to the drive's Percom Block, enabling compatibility between densities by allowing mixed reads where possible, though full cross-density access required matching formats to avoid errors in sector addressing or encoding mismatches.[44] While standard formats capped at 360 KB, custom high-density modifications using third-party drives or firmware hacks extended capacities up to approximately 1 MB by increasing tracks, sectors, or effective bytes per sector beyond official specifications, though these remained non-standard and lacked broad DOS support.[44]Hardware Compatibility and Extensions

Atari DOS was designed to interface with the Atari 8-bit family's Serial Input/Output (SIO) bus, enabling daisy-chaining of peripherals such as disk drives. The SIO chain supported up to eight devices, including the Atari 810 single-density drive (90 KB capacity), the Atari 1050 enhanced-density drive (130 KB capacity), and the later Atari XF551 double-density, double-sided drive (up to 360 KB capacity). These drives connected via the SIO port on the computer or previous device in the chain, allowing sequential access without dedicated controller cards, though power-on sequencing and cable quality affected reliability.[47][48] In 1985, Atari introduced support for RAM-based storage extensions through DOS 2.5, utilizing the additional 64 KB in the Atari 130XE as a high-speed RAM disk that emulated floppy sectors for faster data access compared to physical drives. This extension effectively provided approximately 52 KB (51.5 KB with DUP.SYS and MEM.SAV loaded) of usable RAM disk space after accounting for DOS overhead, reducing load times for frequently accessed files by treating the memory as virtual sectors.[49] Later hardware extensions in the 1990s included the IDE Plus 2.0 interface, which connected ATA/IDE hard drives or CompactFlash cards to Atari XL/XE systems via the PBI or cartridge port, incorporating a DOS translation layer to map hard disk partitions to Atari DOS file systems like those in DOS 2.5 or third-party variants. This allowed seamless integration of larger storage (up to several GB) while maintaining compatibility with floppy-formatted disks through software emulation.[50] Other notable extensions included the Happy 1050 upgrade for the 1050 drive, which added hardware switches for density selection, enabling true double-density operation (180 KB per side) beyond the stock enhanced density and supporting Percom Block configuration for custom sector layouts. On Atari XE models like the 65XE, the Parallel Bus Interface (PBI) port provided direct, unbuffered access to the computer's address and data lines, facilitating high-speed connections to external storage without SIO bottlenecks.[51][52] Despite these advancements, hardware compatibility challenges arose from density mismatches between drives and disks, often resulting in read errors such as sector misalignment or checksum failures when attempting to access single-density media on enhanced-density hardware. Resolving such issues typically required custom drivers or utilities to detect and adjust density on-the-fly, as standard Atari DOS versions like 2.5 lacked automatic handling for all combinations.[53][54]Comparisons and Legacy

Feature Comparisons

Atari DOS versions, particularly 2.0S and 2.5, exhibited relatively modest file copy speeds limited by the standard SIO interface at 19,200 baud, achieving approximately 1 KB per second or 60 KB per minute on stock hardware like the 1050 drive.[55] In contrast, third-party implementations such as SpartaDOS could achieve 2-5 times faster transfer rates—up to around 5 KB per second—with compatible hardware modifications like the US Doubler or Happy 1050 enhancements, significantly reducing copy times for large files.[16][56] Official Atari DOS relied on a menu-driven interface for usability, accessible by typing "DOS" from BASIC, which presented numbered options for tasks like copying, deleting, or formatting files, making it approachable for beginners but slower for repetitive operations.[16] Third-party systems like SpartaDOS and its derivatives shifted to a command-line interface modeled after MS-DOS, allowing direct entry of commands such as "COPY" or "DIR" for quicker, scriptable workflows once users learned the syntax, though this required more familiarity and offered less hand-holding than menus.[16][57] Advanced features in official Atari DOS were limited; for instance, versions 2.0S and 2.5 lacked native support for subdirectories, restricting file organization to flat structures on disks with up to 720 or 1,010 sectors depending on density.[16] MyDOS and SpartaDOS addressed this by incorporating hierarchical subdirectories as standard, enabling nested folders with up to 128 files per directory and better management of larger storage volumes, such as up to 16 MB disks.[16][57] All Atari DOS variants maintained compatibility with core Atari disk formats, including single-density (90 KB) and enhanced-density (130 KB) on 1050 drives, ensuring seamless reading of official media.[16] Third-party DOS like SpartaDOS X extended this to high-density formats on XF551 drives and added support for hard drives or IDE interfaces via dedicated drivers, such as those for Indus GT or SIO2IDE adapters, accommodating larger capacities up to 16 MB or more without altering native Atari file structures.[57][58]| DOS Variant | Approximate Memory Footprint (MEMLO Address, ~KB Used) |

|---|---|

| Official DOS 2.0S | $1CFC (~7.3 KB)[59] |

| Official DOS 2.5 | $1E1C (~7.7 KB)[59] |

| MyDOS 4.50 | $1EE9 (~7.9 KB)[59] |

| SpartaDOS 3.2 | $17A2 (~6.0 KB)[59] |

| LiteDOS 2.06 | ~2 KB[43] |

Modern Relevance and Preservation

In the realm of emulation, Atari DOS remains accessible through modern software tools that faithfully replicate the original 8-bit Atari hardware environment. Altirra, a highly accurate emulator for Atari 8-bit systems, supports all major versions of Atari DOS, including DOS 2, MyDOS, and SpartaDOS, enabling users to run original disk images without physical hardware.[60] Similarly, the Atari800 emulator, an open-source project available across multiple platforms, provides comprehensive compatibility with Atari DOS variants, allowing for the execution of legacy software in a virtualized setting.[61] These emulators preserve the operational integrity of Atari DOS by handling its file systems and SIO (Serial Input/Output) protocols, facilitating archival and study of historical computing artifacts. Preservation efforts extend to disk image formats like .ATR, which capture the exact sector data from original Atari floppy disks, ensuring bit-for-bit fidelity for DOS-managed files across single- and double-density media.[44] This format, widely supported by emulators and archival tools, has become the standard for safeguarding Atari DOS content against media degradation. On the hardware side, contemporary adaptations such as USB-based floppy emulators, exemplified by the SIO2PC device, interface modern computers with original Atari machines via the SIO port, emulating disk drives to load and run DOS environments directly on vintage hardware.[62] FPGA-based recreations further enhance this by providing customizable, high-fidelity peripheral simulations, bridging the gap between legacy systems and current technology for hobbyists seeking authentic experiences. The Atari community plays a pivotal role in sustaining Atari DOS through active online forums like AtariAge, where enthusiasts share resources, including ROM images and disk archives, fostering collaborative preservation projects.[63] Open-source initiatives, such as RespeQt (also known as AspeQt), offer virtual drive emulation that integrates seamlessly with SIO2PC hardware, allowing users to mount .ATR images as functional disks on real Atari systems.[64] However, preservation faces significant challenges, including the legal ambiguity surrounding ROM distribution—Atari system ROMs are not unequivocally public domain, complicating sharing and requiring users to rely on personal dumps for legality.[65] Data recovery from aging 5.25-inch floppies poses another hurdle, as magnetic degradation and copy protection schemes demand specialized tools to read damaged sectors without loss.[66] As of 2025, Atari DOS occupies a niche in hobbyist retro computing, where it supports experimentation with original peripherals and software on emulated or restored hardware, appealing to collectors and tinkerers. Its influence persists in 6502 processor education, as the DOS environment exemplifies early operating system design principles; in 2025, celebrations of the 6502's 50th anniversary included community projects like webGL demos and custom computer badges, inspiring modern open-source recreations and instructional resources.[67][68] This ongoing relevance underscores Atari DOS's role in broader retro computing culture, promoting hands-on learning in assembly programming and disk management for educational purposes.[69]References

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=Atari%20DOS%203

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=Atari%20DOS%204

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=MyDOS

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=OSS%20DOS%20XL

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=SuperDOS

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=BEWE%20DOS%201.30%20Manual

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=DOS

- https://atariwiki.org/wiki/Wiki.jsp?page=SpartaDOS