Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

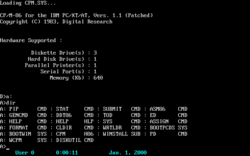

| CP/M | |

|---|---|

A screenshot of CP/M-86 | |

| Developer | Digital Research, Inc., Gary Kildall |

| Written in | PL/M, Assembly language |

| Working state | Historical |

| Source model | Originally closed source, now open source[1] |

| Initial release | 1974 |

| Latest release | 3.1 / 1983[2] |

| Available in | English |

| Update method | Re-installation |

| Package manager | None |

| Supported platforms | Intel 8080, Intel 8085, Zilog Z80, Zilog Z8000, Intel 8086, Motorola 68000 |

| Kernel type | Monolithic kernel |

| Influenced by | RT-11, OS/8 |

| Default user interface | Command-line interface (CCP.COM) |

| License | Originally proprietary, now BSD-like |

| Succeeded by | MP/M, CP/M-86 |

| Official website | Digital Research CP/M page |

CP/M,[3] originally standing for Control Program/Monitor[4] and later Control Program for Microcomputers,[5][6][7] is a mass-market operating system created in 1974 for Intel 8080/85-based microcomputers by Gary Kildall of Digital Research, Inc. CP/M is a disk operating system[8] and its purpose is to organize files on a magnetic storage medium, and to load and run programs stored on a disk. Initially confined to single-tasking on 8-bit processors and no more than 64 kilobytes of memory, later versions of CP/M added multi-user variations and were migrated to 16-bit processors.

CP/M's core components are the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS), the Basic Disk Operating System (BDOS), and the Console Command Processor (CCP). The BIOS consists of drivers that deal with devices and system hardware. The BDOS implements the file system and provides system services to applications. The CCP is the command-line interpreter and provides some built-in commands.

CP/M eventually became the de facto standard and the dominant operating system for microcomputers,[9] in combination with the S-100 bus computers. This computer platform was widely used in business through the late 1970s and into the mid-1980s.[10] CP/M increased the market size for both hardware and software by greatly reducing the amount of programming required to port an application to a new manufacturer's computer.[11][12] An important driver of software innovation was the advent of (comparatively) low-cost microcomputers running CP/M, as independent programmers and hackers bought them and shared their creations in user groups.[13] CP/M was eventually displaced in popularity by DOS following the 1981 introduction of the IBM PC.

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]Gary Kildall originally developed CP/M during 1974,[5][6] as an operating system to run on an Intel Intellec-8 development system, equipped with a Shugart Associates 8-inch floppy-disk drive interfaced via a custom floppy-disk controller.[14] It was written in Kildall's own PL/M (Programming Language for Microcomputers).[15] Various aspects of CP/M were influenced by the TOPS-10 operating system of the DECsystem-10 mainframe computer, which Kildall had used as a development environment.[16][17][18]

CP/M supported a wide range of computers based on the 8080 and Z80 CPUs.[19] An early outside licensee of CP/M was Gnat Computers, an early microcomputer developer out of San Diego, California. In 1977, the company was granted the license to use CP/M 1.0 for any micro they desired for $90. Within the year, demand for CP/M was so high that Digital Research was able to increase the license to tens of thousands of dollars.[20]

Under Kildall's direction, the development of CP/M 2.0 was mostly carried out by John Pierce in 1978. Kathryn Strutynski, a friend of Kildall from Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), became the fourth employee of Digital Research Inc. in early 1979. She started by debugging CP/M 2.0, and later became influential as key developer for CP/M 2.2 and CP/M Plus. Other early developers of the CP/M base included Robert "Bob" Silberstein and David "Dave" K. Brown.[21][22]

CP/M originally stood for "Control Program/Monitor",[3] a name which implies a resident monitor—a primitive precursor to the operating system. However, during the conversion of CP/M to a commercial product, trademark registration documents filed in November 1977 gave the product's name as "Control Program for Microcomputers".[6] The CP/M name follows a prevailing naming scheme of the time, as in Kildall's PL/M language, and Prime Computer's PL/P (Programming Language for Prime), both suggesting IBM's PL/I; and IBM's CP/CMS operating system, which Kildall had used when working at the NPS. This renaming of CP/M was part of a larger effort by Kildall and his wife with business partner, Dorothy McEwen[4] to convert Kildall's personal project of CP/M and the Intel-contracted PL/M compiler into a commercial enterprise. The Kildalls intended to establish the Digital Research brand and its product lines as synonymous with "microcomputer" in the consumer's mind, similar to what IBM and Microsoft together later successfully accomplished in making "personal computer" synonymous with their product offerings. Intergalactic Digital Research, Inc. was later renamed via a corporation change-of-name filing to Digital Research, Inc.[4]

Initial success

[edit]

By September 1981, Digital Research had sold more than 250,000 CP/M licenses; InfoWorld stated that the actual market was likely larger because of sublicenses. Many different companies produced CP/M-based computers for many different markets; the magazine stated that "CP/M is well on its way to establishing itself as the small-computer operating system".[23] Even companies with proprietary operating systems, such as Heath/Zenith (HDOS), offered CP/M as an alternative for their 8080/Z80-based systems; by contrast, no comparable standard existed for computers based on the also popular 6502 CPU.[19] They supported CP/M because of its large library of software. The Xerox 820 ran the operating system because "where there are literally thousands of programs written for it, it would be unwise not to take advantage of it", Xerox said.[24] (Xerox included a Howard W. Sams CP/M manual as compensation for Digital Research's documentation, which InfoWorld described as atrocious,[25] incomplete, incomprehensible, and poorly indexed.[26]) By 1984, Columbia University used the same source code to build Kermit binaries for more than a dozen different CP/M systems, plus two generic versions.[27] The operating system was described as a "software bus",[28][29] allowing multiple programs to interact with different hardware in a standardized way.[30] Programs written for CP/M were typically portable among different machines, usually requiring only the specification of the escape sequences for control of the screen and printer. This portability made CP/M popular, and much more software was written for CP/M than for operating systems that ran on only one brand of hardware. One restriction on portability was that certain programs used the extended instruction set of the Z80 processor and would not operate on an 8080 or 8085 processor. Another was graphics routines, especially in games and graphics programs, which were generally machine-specific as they used direct hardware access for speed, bypassing the OS and BIOS (this was also a common problem in early DOS machines).[citation needed]

Bill Gates claimed that the Apple II with a Z-80 SoftCard was the single most-popular CP/M hardware platform.[31] Digital Research stated in 1982 that the operating system had been licensed for more than 450 types of computer systems.[32] Many different brands of machines ran the operating system, some notable examples being the Altair 8800, the IMSAI 8080, the Osborne 1 and Kaypro luggables, and MSX computers. The best-selling CP/M-capable system of all time was probably the Amstrad PCW. In the UK, CP/M was also available on Research Machines educational computers (with the CP/M source code published as an educational resource), and for the BBC Micro when equipped with a Z80 co-processor. Furthermore, it was available for the Amstrad CPC series, the Commodore 128, TRS-80, and later models of the ZX Spectrum. CP/M 3 was also used on the NIAT, a custom handheld computer designed for A. C. Nielsen's internal use with 1 MB of SSD memory.

Multi-user

[edit]In 1979, a multi-user compatible derivative of CP/M was released. MP/M allowed multiple users to connect to a single computer, using multiple terminals to provide each user with a screen and keyboard. Later versions ran on 16-bit processors.

CP/M Plus

[edit]

The last 8-bit version of CP/M was version 3, often called CP/M Plus, released in 1983.[21] Its BDOS was designed by David K. Brown.[21] It incorporated the bank switching memory management of MP/M in a single-user single-task operating system compatible with CP/M 2.2 applications. CP/M 3 could therefore use more than 64 KB of memory on an 8080 or Z80 processor. The system could be configured to support date stamping of files.[21] The operating system distribution software also included a relocating assembler and linker.[2] CP/M 3 was available for the last generation of 8-bit computers, notably the Amstrad PCW, the Amstrad CPC, the ZX Spectrum +3, the Commodore 128, MSX machines and the Radio Shack TRS-80 Model 4.[33]

16-bit versions

[edit]

There were versions of CP/M for some 16-bit CPUs as well.

The first version in the 16-bit family was CP/M-86 for the Intel 8086 in November 1981.[34] Kathryn Strutynski was the project manager for the evolving CP/M-86 line of operating systems.[21][22] At this point, the original 8-bit CP/M became known by the retronym CP/M-80 to avoid confusion.[34]

CP/M-86 was expected to be the standard operating system of the new IBM PCs, but DRI and IBM were unable to negotiate development and licensing terms. IBM turned to Microsoft instead, and Microsoft delivered PC DOS based on 86-DOS. Although CP/M-86 became an option for the IBM PC after DRI threatened legal action, it never overtook Microsoft's system. Most customers were repelled by the significantly greater price IBM charged for CP/M-86 over PC DOS (US$240 and US$40, respectively).[35]

When Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) put out the Rainbow 100 to compete with IBM, it came with CP/M-80 using a Z80 chip, CP/M-86 or MS-DOS using an 8088 microprocessor, or CP/M-86/80 using both. The Z80 and 8088 CPUs ran concurrently.[36][37] A benefit of the Rainbow was that it could continue to run 8-bit CP/M software, preserving a user's possibly sizable investment as they moved into the 16-bit world of MS-DOS.[36] A similar dual-processor adaption for the CompuPro System 816 was named CP/M 8-16. The CP/M-86 adaptation for the 8085/8088-based Zenith Z-100 also supported running programs for both of its CPUs.

Soon following CP/M-86, another 16-bit version of CP/M was CP/M-68K for the Motorola 68000. The original version of CP/M-68K in 1982 was written in Pascal/MT+68k, but it was ported to C later on. CP/M-68K, already running on the Motorola EXORmacs systems, was initially to be used in the Atari ST computer, but Atari decided to go with a newer disk operating system called GEMDOS. CP/M-68K was also used on the SORD M68 and M68MX computers.[38]

In 1982, there was also a port from CP/M-68K to the 16-bit Zilog Z8000 for the Olivetti M20, written in C, named CP/M-8000.[39][40]

These 16-bit versions of CP/M required application programs to be re-compiled for the new CPUs. Some programs written in assembly language could be automatically translated for a new processor. One tool for this was Digital Research's XLT86, which translated .ASM source code for the Intel 8080 processor into .A86 source code for the Intel 8086. The translator would also optimize the output for code size and take care of calling conventions, so that CP/M-80 and MP/M-80 programs could be ported to the CP/M-86 and MP/M-86 platforms automatically. XLT86 itself was written in PL/I-80 and was available for CP/M-80 platforms as well as for VAX/VMS.[41]

Displacement by MS-DOS

[edit]By the early 1980s an estimated 2000 CP/M applications existed.[42] Many expected that it would be the standard operating system for 16-bit computers.[43] In 1980 IBM approached Digital Research, at Bill Gates' suggestion,[44] to license a forthcoming version of CP/M for its new product, the IBM Personal Computer. Upon the failure to obtain a signed non-disclosure agreement, the talks failed, and IBM instead contracted with Microsoft to provide an operating system.[45]

Many of the basic concepts and mechanisms of early versions of MS-DOS resemble those of CP/M. Internals like file-handling data structures are identical, and both refer to disk drives with a letter (A:, B:, etc.). MS-DOS's main innovation was its FAT file system. This similarity made it easier to port popular CP/M software like WordStar and dBase. However, CP/M's concept of separate user areas for files on the same disk was never ported to MS-DOS. Since MS-DOS has access to more memory (as few IBM PCs were sold with less than 64 KB of memory, while CP/M can run in 16 KB if necessary), more commands are built into the command-line shell, making MS-DOS somewhat faster and easier to use on floppy-based computers.

Although one of the first peripherals for the IBM PC was the Baby Blue card, a SoftCard-like expansion card that lets the PC run 8-bit CP/M software like WordStar not yet available for it,[42] and BYTE in 1982 described MS-DOS and CP/M as David and Goliath, the magazine stated that MS-DOS was "much more user-friendly, faster, with many more advantages, and fewer disadvantages".[32] InfoWorld stated in 1984 that efforts to introduce CP/M to the home market had been largely unsuccessful and most CP/M software was too expensive for home users.[46] In 1986 the magazine stated that Kaypro had stopped production of 8-bit CP/M-based models to concentrate on sales of MS-DOS compatible systems, long after most other vendors had ceased production of new equipment and software for CP/M.[47] CP/M rapidly lost market share as the microcomputing market moved to the IBM-compatible platform, and never regained its former popularity. Byte magazine, one of the leading industry magazines for microcomputers, essentially ceased covering CP/M products within a few years of the introduction of the IBM PC. For example, in 1983 there were still a few advertisements for S-100 boards and articles on CP/M software, but by 1987 these were no longer found in the magazine.

Later versions of CP/M-86 made significant strides in performance and usability and were made compatible with MS-DOS. To reflect this compatibility the name was changed, and CP/M-86 became DOS Plus, which in turn became DR-DOS.

ZCPR

[edit]ZCPR[48] (the Z80 Command Processor Replacement) was introduced on 2 February 1982 as a drop-in replacement for the standard Digital Research console command processor (CCP) and was initially written by a group of computer hobbyists who called themselves "The CCP Group". They were Frank Wancho, Keith Petersen (the archivist behind Simtel at the time), Ron Fowler, Charlie Strom, Bob Mathias, and Richard Conn. Richard was, in fact, the driving force in this group (all of whom maintained contact through email).

ZCPR1 was released on a disk put out by SIG/M (Special Interest Group/Microcomputers), a part of the Amateur Computer Club of New Jersey.

ZCPR2 was released on 14 February 1983. It was released as a set of ten disks from SIG/M. ZCPR2 was upgraded to 2.3, and also was released in 8080 code, permitting the use of ZCPR2 on 8080 and 8085 systems.

Conn and Frank Gaude formed Echelon Inc. to publish the next version of ZCPR as a commercial product, while still distributing it as free software.[49] ZCPR3[50] was released on 14 July 1984, as a set of nine disks from SIG/M. The code for ZCPR3 could also be compiled (with reduced features) for the 8080 and would run on systems that did not have the requisite Z80 microprocessor. Features of ZCPR as of version 3 included shells, aliases, I/O redirection, flow control, named directories, search paths, custom menus, passwords, and online help. In January 1987, Richard Conn stopped developing ZCPR, and Echelon asked Jay Sage (who already had a privately enhanced ZCPR 3.1) to continue work on it. Thus, ZCPR 3.3 was developed and released. ZCPR 3.3 no longer supported the 8080 series of microprocessors, and added the most features of any upgrade in the ZCPR line. ZCPR 3.3 also included a full complement of utilities with considerably extended capabilities. While enthusiastically supported by the CP/M user base of the time, ZCPR alone was insufficient to slow the demise of CP/M.

Hardware model

[edit]

A minimal 8-bit CP/M system would contain the following components:

- A computer terminal using the ASCII character set

- An Intel 8080 (and later the 8085) or Zilog Z80 microprocessor

- At least 16 kilobytes of RAM, beginning at address 0

- A means to bootstrap the first sector of the diskette

- At least one floppy-disk drive

The only hardware system that CP/M, as sold by Digital Research, would support was the Intel 8080 Development System. Manufacturers of CP/M-compatible systems customized portions of the operating system for their own combination of installed memory, disk drives, and console devices. CP/M would also run on systems based on the Zilog Z80 processor since the Z80 was compatible with 8080 code. While the Digital Research distributed core of CP/M (BDOS, CCP, core transient commands) did not use any of the Z80-specific instructions, many Z80-based systems used Z80 code in the system-specific BIOS, and many applications were dedicated to Z80-based CP/M machines.

Digital Research subsequently partnered with Zilog and American Microsystems to produce Personal CP/M, a ROM-based version of the operating system aimed at lower-cost systems that could potentially be equipped without disk drives.[53] First featured in the Sharp MZ-800, a cassette-based system with optional disk drives,[54] Personal CP/M was described as having been "rewritten to take advantage of the enhanced Z-80 instruction set" as opposed to preserving portability with the 8080. American Microsystems announced a Z80-compatible microprocessor, the S83, featuring 8 KB of in-package ROM for the operating system and BIOS, together with comprehensive logic for interfacing with 64-kilobit dynamic RAM devices.[55] Unit pricing of the S83 was quoted as $32 in 1,000 unit quantities.[56]

On most machines the bootstrap was a minimal bootloader in ROM combined with some means of minimal bank switching or a means of injecting code on the bus (since the 8080 needs to see boot code at Address 0 for start-up, while CP/M needs RAM there); for others, this bootstrap had to be entered into memory using front-panel controls each time the system was started.

CP/M used the 7-bit ASCII set. The other 128 characters made possible by the 8-bit byte were not standardized. For example, one Kaypro used them for Greek characters, and Osborne machines used the 8th bit set to indicate an underlined character. WordStar used the 8th bit as an end-of-word marker. International CP/M systems most commonly used the ISO 646 norm for localized character sets, replacing certain ASCII characters with localized characters rather than adding them beyond the 7-bit boundary.

Components

[edit]While running, the CP/M operating system loaded into memory has three components:[3][57]: 2 [58]: 1 [59]: 3, 4–5 [60]: 1-4–1-6

- Basic Input/Output System (BIOS),

- Basic Disk Operating System (BDOS),

- Console Command Processor (CCP).

The BIOS and BDOS are memory-resident, while the CCP is memory-resident unless overwritten by an application, in which case it is automatically reloaded after the application finished running. A number of transient commands for standard utilities are also provided. The transient commands reside in files with the extension .COM on disk.

The BIOS directly controls hardware components other than the CPU and main memory. It contains functions such as character input and output and the reading and writing of disk sectors. The BDOS implements the CP/M file system and some input/output abstractions (such as redirection) on top of the BIOS. The CCP takes user commands and either executes them directly (internal commands such as DIR to show a directory or ERA to delete a file) or loads and starts an executable file of the given name (transient commands such as PIP.COM to copy files or STAT.COM to show various file and system information). Third-party applications for CP/M are also essentially transient commands.

The BDOS, CCP and standard transient commands are the same in all installations of a particular revision of CP/M, but the BIOS portion is always adapted to the particular hardware.

Adding memory to a computer, for example, means that the CP/M system must be reinstalled to allow transient programs to use the additional memory space. A utility program (MOVCPM) is provided with system distribution that allows relocating the object code to different memory areas. The utility program adjusts the addresses in absolute jump and subroutine call instructions to new addresses required by the new location of the operating system in processor memory. This newly patched version can then be saved on a new disk, allowing application programs to access the additional memory made available by moving the system components. Once installed, the operating system (BIOS, BDOS and CCP) is stored in reserved areas at the beginning of any disk which can be used to boot the system. On start-up, the bootloader (usually contained in a ROM firmware chip) loads the operating system from the disk in drive A:.

By modern standards CP/M is primitive, owing to the extreme constraints on program size. With version 1.0 there is no provision for detecting a changed disk. If a user changes disks without manually rereading the disk directory the system writes on the new disk using the old disk's directory information, ruining the data stored on the disk. From version 1.1 or 1.2 onwards, changing a disk then trying to write to it before its directory is read will cause a fatal error to be signalled. This avoids overwriting the disk but requires a reboot and loss of the data to be stored on disk.

The majority of the complexity in CP/M is isolated in the BDOS, and to a lesser extent, the CCP and transient commands. This meant that by porting the limited number of simple routines in the BIOS to a particular hardware platform, the entire OS would work. This significantly reduced the development time needed to support new machines, and was one of the main reasons for CP/M's widespread use. Today this sort of abstraction is common to most OSs (a hardware abstraction layer), but at the time of CP/M's birth, OSs were typically intended to run on only one machine platform, and multilayer designs were considered unnecessary.

Console Command Processor

[edit]

DIR command on a Commodore 128 home computerThe Console Command Processor, or CCP, accepts input from the keyboard and conveys results to the terminal. CP/M itself works with either a printing terminal or a video terminal. All CP/M commands have to be typed in on the command line. The console most often displays the A> prompt, to indicate the current default disk drive. When used with a video terminal, this is usually followed by a blinking cursor supplied by the terminal. The CCP awaits input from the user. A CCP internal command, of the form drive letter followed by a colon, can be used to select the default drive. For example, typing B: and pressing enter at the command prompt changes the default drive to B, and the command prompt then becomes B> to indicate this change.

CP/M's command-line interface was patterned after the Concise Command Language used in operating systems from Digital Equipment, such as RT-11 for the PDP-11 and OS/8 for the PDP-8.[citation needed] Commands take the form of a keyword followed by a list of parameters separated by spaces or special characters. Similar to a Unix shell builtin, if an internal command is recognized, it is carried out by the CCP itself. Otherwise it attempts to find an executable file on the currently logged disk drive and (in later versions) user area, loads it, and passes it any additional parameters from the command line. These are referred to as "transient" programs. On completion, BDOS will reload the CCP if it has been overwritten by application programs — this allows transient programs a larger memory space.

The commands themselves can sometimes be obscure. For instance, the command to duplicate files is named PIP (Peripheral-Interchange-Program), the name of the old DEC utility used for that purpose. The format of parameters given to a program was not standardized, so that there is no single option character that differentiated options from file names. Different programs can and do use different characters.

The CP/M Console Command Processor includes DIR, ERA, REN, SAVE, TYPE, and USER as built-in commands.[61] Transient commands in CP/M include ASM, DDT, DUMP, ED, LOAD, MOVCPM, PIP, STAT, SUBMIT, and SYSGEN.[61]

CP/M Plus (CP/M Version 3) includes DIR (display list of files from a directory except those marked with the SYS attribute), DIRSYS / DIRS (list files marked with the SYS attribute in the directory), ERASE / ERA (delete a file), RENAME / REN (rename a file), TYPE / TYP (display contents of an ASCII character file), and USER / USE (change user number) as built-in commands:[62] CP/M 3 allows the user to abbreviate the built-in commands.[63] Transient commands in CP/M 3 include COPYSYS, DATE, DEVICE, DUMP, ED, GET, HELP, HEXCOM, INITDIR, LINK, MAC, PIP, PUT, RMAC, SET, SETDEF, SHOW, SID, SUBMIT, and XREF.[63]

Basic Disk Operating System

[edit]The Basic Disk Operating System,[15][14] or BDOS,[15][14] provides access to such operations as opening a file, output to the console, or printing. Application programs load processor registers with a function code for the operation, and addresses for parameters or memory buffers, and call a fixed address in memory. Since the address is the same independent of the amount of memory in the system, application programs run the same way for any type or configuration of hardware.

Basic Input Output System

[edit]

The Basic Input Output System or BIOS,[15][14] provides the lowest level functions required by the operating system.

These include reading or writing single characters to the system console and reading or writing a sector of data from the disk. The BDOS handles some of the buffering of data from the diskette, but before CP/M 3.0 it assumes a disk sector size fixed at 128 bytes, as used on single-density 8-inch floppy disks. Since most 5.25-inch disk formats use larger sectors, the blocking and deblocking and the management of a disk buffer area is handled by model-specific code in the BIOS.

Customization is required because hardware choices are not constrained by compatibility with any one popular standard. For example, some manufacturers designed built-in integrated video display systems, while others relied on separate computer terminals. Serial ports for printers and modems can use different types of UART chips, and port addresses are not fixed. Some machines use memory-mapped I/O instead of the 8080 I/O address space. All of these variations in the hardware are concealed from other modules of the system by use of the BIOS, which uses standard entry points for the services required to run CP/M such as character I/O or accessing a disk block. Since support for serial communication to a modem is very rudimentary in the BIOS or may be absent altogether, it is common practice for CP/M programs that use modems to have a user-installed overlay containing all the code required to access a particular machine's serial port.

Applications

[edit]

WordStar, one of the first widely used word processors, and dBase, an early and popular database program for microcomputers, were originally written for CP/M. Two early outliners, KAMAS (Knowledge and Mind Amplification System) and its cut-down successor Out-Think (without programming facilities and retooled for 8080/V20 compatibility) were also written for CP/M, though later rewritten for MS-DOS. Turbo Pascal, the ancestor of Borland Delphi, and Multiplan, the ancestor of Microsoft Excel, also debuted on CP/M before MS-DOS versions became available. VisiCalc, the first-ever spreadsheet program, was made available for CP/M. Another company, Sorcim, created its SuperCalc spreadsheet for CP/M, which would go on to become the market leader and de facto standard on CP/M. Supercalc would go on to be a competitor in the spreadsheet market in the MS-DOS world. AutoCAD, a CAD application from Autodesk debuted on CP/M. A host of compilers and interpreters for popular programming languages of the time (such as BASIC, Borland's Turbo Pascal, FORTRAN and even PL/I[64]) were available, among them several of the earliest Microsoft products.

CP/M software often comes with installers that adapts it to a wide variety of computers.[65] A Kaypro II owner, for example, would obtain software on Xerox 820 format, then copy it to and run it from Kaypro-format disks.[66] The source code for BASIC programs is easily accessible, and most forms of copy protection are ineffective on the operating system.[67] While copy-protected programs for contemporary operating systems often use nonstandard disk formats that other software cannot read, CP/M users expect cross-software compatibility for their files; an unreadable disk is by definition not in a CP/M format.[68]

The lack of standardized graphics support limited video games, but various character and text-based games were ported, such as Telengard,[69] Gorillas,[70] Hamurabi, Lunar Lander, along with early interactive fiction including the Zork series and Colossal Cave Adventure. Text adventure specialist Infocom was one of the few publishers to consistently release their games in CP/M format. Lifeboat Associates started collecting and distributing user-written "free" software. One of the first was XMODEM, which allowed reliable file transfers via modem and phone line. Another program native to CP/M was the outline processor KAMAS.[citation needed]

Transient Program Area

[edit]In the original version of CP/M for the 8080, 8085, and Z80, the read/write memory between address 0100 hexadecimal and the location just before address stored at 0006H (the lowest address of the BDOS) is the Transient Program Area (TPA) available for CP/M application programs.[57]: 2, 233 Although all Z80 and 8080 processors could address 64 kilobytes of memory, the amount available for application programs could vary, depending on the design of the particular computer. Some computers used large parts of the address space for such things as BIOS ROMs, or video display memory. As a result, some systems had more TPA memory available than others. Bank switching was a common technique that allowed systems to have a large TPA while switching out ROM or video memory space as needed. CP/M 3.0 allowed parts of the BDOS to be in bank-switched memory as well.

Debugging application

[edit]CP/M came with a Dynamic Debugging Tool, nicknamed DDT (after the insecticide, i.e. a bug-killer), which allowed memory and program modules to be examined and manipulated, and allowed a program to be executed one step at a time.[71][72][73]

Resident programs

[edit]CP/M originally did not support the equivalent of terminate and stay resident (TSR) programs as under DOS. Programmers could write software that could intercept certain operating system calls and extend or alter their functionality. Using this capability, programmers developed and sold auxiliary desk accessory programs, such as SmartKey, a keyboard utility to assign any string of bytes to any key.[74] CP/M 3, however, added support for dynamically loadable Resident System Extensions (RSX).[62][21] A so-called null command file could be used to allow CCP to load an RSX without a transient program.[62][21] Similar solutions like RSMs (for Resident System Modules) were also retrofitted to CP/M 2.2 systems by third-parties.[75][76][77]

Software installation

[edit]Although CP/M provided some hardware abstraction to standardize the interface to disk I/O or console I/O, application programs still typically required installation to make use of all the features of such equipment as printers and terminals. Often these were controlled by escape sequences which had to be altered for different devices. For example, the escape sequence to select bold face on a printer would have differed among manufacturers, and sometimes among models within a manufacturer's range. This procedure was not defined by the operating system; a user would typically run an installation program that would either allow selection from a range of devices, or else allow feature-by-feature editing of the escape sequences required to access a function. This had to be repeated for each application program, since there was no central operating system service provided for these devices.

The initialization codes for each model of printer had to be written into the application. To use a program such as Wordstar with more than one printer (say, a fast dot-matrix printer or a slower but presentation-quality daisy wheel printer), a separate version of Wordstar had to be prepared, and one had to load the Wordstar version that corresponded to the printer selected (and exiting and reloading to change printers).

Disk formats

[edit]IBM System/34 and IBM 3740's 128 byte/sector, single-density, single-sided format is CP/M's standard 8-inch floppy-disk format. No standard 5.25-inch CP/M disk format exists, with Kaypro, Morrow Designs, Osborne, and others each using their own.[78][79][25][80][68] Certain formats were more popular than others. Most software was available in the Xerox 820 format, and other computers such as the Kaypro II were compatible with it,[66][81] but InfoWorld estimated in September 1981 that "about two dozen formats were popular enough that software creators had to consider them to reach the broadest possible market".[23] JRT Pascal, for example, provided versions on 5.25-inch disk for North Star, Osborne, Apple, Heath/Zenith hard sector and soft sector, and Superbrain, and one 8-inch version.[82] Ellis Computing also offered its software for both Heath formats, and 16 other 5.25-inch formats including two different TRS-80 CP/M modifications.[83] Lifetree and some other software distributors also converted CP/M applications to various systems.[84]

Various formats were used depending on the characteristics of particular systems and to some degree the choices of the designers. CP/M supports options to control the size of reserved and directory areas on the disk, and the mapping between logical disk sectors (as seen by CP/M programs) and physical sectors as allocated on the disk. There are many ways to customize these parameters for every system[85] but once they are set, no standardized way exists for a system to load parameters from a disk formatted on another system.

While almost every CP/M system with 8-inch drives can read the aforementioned IBM single-sided, single-density format, for other formats the degree of portability between different CP/M machines depends on the type of disk drive and controller used since many different floppy types existed in the CP/M era in both 8-inch and 5.25-inch sizes.[79] Disks can be hard or soft sectored, single or double density, single or double sided, 35 track, 40 track, 77 track, or 80 track, and the sector layout, size and interleave can vary widely as well. Although translation programs can allow the user to read disk types from different machines, the drive type and controller are also factors. By 1982, soft-sector, single-sided, 40-track 5.25-inch disks had become the most popular format to distribute CP/M software on as they were used by the most common consumer-level machines of that time, such as the Apple II, TRS-80, Osborne 1, Kaypro II, and IBM PC. A translation program allows the user to read any disks on his machine that had a similar format; for example, the Kaypro II can read TRS-80, Osborne, IBM PC, and Epson disks. Other disk types such as 80 track or hard sectored are completely impossible to read. The first half of double-sided disks (like those of the Epson QX-10) can be read because CP/M accessed disk tracks sequentially with track 0 being the first (outermost) track of side 1 and track 79 (on a 40-track disk) being the last (innermost) track of side 2. Apple II users are unable to use anything but Apple's GCR format and so have to obtain CP/M software on Apple format disks or else transfer it via serial link.

The fragmented CP/M market, requiring distributors either to stock multiple formats of disks or to invest in multiformat duplication equipment, compared with the more standardized IBM PC disk formats, was a contributing factor to the rapid obsolescence of CP/M after 1981.

One of the last notable CP/M-capable machines to appear was the Commodore 128 in 1985, which had a Z80 for CP/M support in addition to its native mode using a 6502-derivative CPU. Using CP/M required either a 1571 or 1581 disk drive which could read soft-sector 40-track MFM-format disks.

The first computer to use a 3.5-inch floppy drive, the Sony SMC-70,[86] ran CP/M 2.2. The Commodore 128, Bondwell-2 laptop, Micromint/Ciarcia SB-180,[87] MSX and TRS-80 Model 4 (running Montezuma CP/M 2.2) also supported the use of CP/M with 3.5-inch floppy disks. CP/AM, Applied Engineering's version of CP/M for the Apple II, also supported 3.5-inch disks (as well as RAM disks on RAM cards compatible with the Apple II Memory Expansion Card).[88] The Amstrad PCW ran CP/M using 3-inch floppy drives at first, and later switched to the 3.5 inch drives.

File system

[edit]File names were specified as a string of up to eight characters, followed by a period, followed by a file name extension of up to three characters ("8.3" filename format). The extension usually identified the type of the file. For example, .COM indicated an executable program file, and .TXT indicated a file containing ASCII text. Characters in filenames entered at the command prompt were converted to upper case, but this was not enforced by the operating system. Programs (MBASIC is a notable example) were able to create filenames containing lower-case letters, which then could not easily be referenced at the command line.

Each disk drive was identified by a drive letter, for example, drive A and drive B. To refer to a file on a specific drive, the drive letter was prefixed to the file name, separated by a colon, e.g., A:FILE.TXT. With no drive letter prefixed, access was to files on the current default drive.[89]

File size was specified as the number of 128-byte records (directly corresponding to disk sectors on 8-inch drives) occupied by a file on the disk. There was no generally supported way of specifying byte-exact file sizes. The current size of a file was maintained in the file's File Control Block (FCB) by the operating system. Since many application programs (such as text editors) prefer to deal with files as sequences of characters rather than as sequences of records, by convention text files were terminated with a control-Z character (ASCII SUB, hexadecimal 1A). Determining the end of a text file therefore involved examining the last record of the file to locate the terminating control-Z. This also meant that inserting a control-Z character into the middle of a file usually had the effect of truncating the text contents of the file.

With the advent of larger removable and fixed disk drives, disk de-blocking formulas were employed which resulted in more disk blocks per logical file allocation block. While this allowed for larger file sizes, it also meant that the smallest file which could be allocated increased in size from 1 KB (on single-density drives) to 2 KB (on double-density drives) and so on, up to 32 KB for a file containing only a single byte. This made for inefficient use of disk space if the disk contained a large number of small files.

File modification time stamps were not supported in releases up to CP/M 2.2, but were an optional feature in MP/M and CP/M 3.0.[21]

CP/M 2.2 had no subdirectories in the file structure, but provided 16 numbered user areas to organize files on a disk. To change user one had to simply type "User X" at the command prompt, X being the user number. Security was non-existent and considered unnecessary on a personal computer. The user area concept was to make the single-user version of CP/M somewhat compatible with multi-user MP/M systems. A common patch for the CP/M and derivative operating systems was to make one user area accessible to the user independent of the currently set user area. A USER command allowed the user area to be changed to any area from 0 to 15. User 0 was the default. If one changed to another user, such as USER 1, the material saved on the disk for this user would only be available to USER 1; USER 2 would not be able to see it or access it. However, files stored in the USER 0 area were accessible to all other users; their location was specified with a prefatory path, since the files of USER 0 were only visible to someone logged in as USER 0. The user area feature arguably had little utility on small floppy disks, but it was useful for organizing files on machines with hard drives. The intent of the feature was to ease use of the same computer for different tasks. For example, a secretary could do data entry, then, after switching USER areas, another employee could use the machine to do billing without their files intermixing.

Graphics

[edit]

Although graphics-capable S-100 systems existed from the commercialization of the S-100 bus, CP/M did not provide any standardized graphics support until 1982 with GSX (Graphics System Extension). Owing to the small amount of available memory, graphics was never a common feature associated with 8-bit CP/M operating systems. Most systems could only display rudimentary ASCII art charts and diagrams in text mode or by using a custom character set. Some computers in the Kaypro line and the TRS-80 Model 4 had video hardware supporting block graphics characters, and these were accessible to assembler programmers and BASIC programmers using the CHR$ command. The Model 4 could display 640 by 240 pixel graphics with an optional high resolution board.

Derivatives

[edit]

Official

[edit]Some companies made official enhancements of CP/M based on Digital Research source code. An example is IMDOS for the IMSAI 8080 computer made by IMS Associates, Inc., a clone of the famous Altair 8800.

Compatible

[edit]Other CP/M compatible OSes were developed independently and made no use of Digital Research code. Some contemporary examples were:

- Cromemco CDOS from Cromemco

- MSX-DOS for the MSX range of computers is CP/M-compatible and can run CP/M programs.

- The Epson QX-10 shipped with a choice of CP/M or the compatible TPM-II or TPM-III.

- The British ZX Spectrum compatible SAM Coupé had an optional CP/M-2.2 compatible OS called Pro-DOS.

- The Amstrad/Schneider CPC series 6xx (disk-based) and PCW series computers were bundled with an CP/M disk pack.

- The Husky computer ran a ROM-based menu-driven program loader called DEMOS which could run many CP/M applications.

- ZSDOS is a replacement BDOS for CP/M-80 2.2 written by Harold F. Bower and Cameron W. Cotrill.

- CPMish is a new FOSS CP/M 2.2-compatible operating system which originally contained no DR code. It includes ZSDOS as its BDOS and ZCPR (see earlier) as the command processor. Since Bryan Sparks, the president of DR owners Lineo, granted permission in 2022 to modify and redistribute CP/M code, developer David Given is updating CPMish with some parts of the original DR CP/M.

- LokiOS is a CP/M 2.2 compatible OS. Version 0.9 was publicly released in 2023 by David Kitson as a solo-written Operating System exercise, intended for the Open Spectrum Project and includes source code for the BIOS, BDOS and Command-line interface as well as other supporting applications and drivers. The distribution also includes original DR Source code and a utility to allow users to hot-swap OS components (e.g., BDOS, CCP) on the fly.

- IS-DOS for the Enterprise computers, written by Intelligent Software.

- VT-DOS for the Videoton TV Computer, written by Intelligent Software.

Enhancements

[edit]Some CP/M compatible operating systems extended the basic functionality so far that they far exceeded the original, for example the multi-processor capable TurboDOS.

Eastern bloc

[edit]A number of CP/M-80 derivatives existed in the former Eastern Bloc under various names, including SCP (Single User Control Program), SCP/M, CP/A,[90] CP/J, CP/KC, CP/KSOB, CP/L, CP/Z, MICRODOS, BCU880, ZOAZ, OS/M, TOS/M, ZSDOS, M/OS, COS-PSA, DOS-PSA, CSOC, CSOS, CZ-CPM, DAC, HC and others.[91][92] There were also CP/M-86 derivatives named SCP1700, CP/K and K8918-OS.[92] They were produced by the East German VEB Robotron and others.[92][91][90]

Legacy

[edit]A number of behaviors exhibited by Microsoft Windows are a result of backward compatibility with MS-DOS, which in turn attempted some backward compatibility with CP/M. The drive letter and 8.3 filename conventions in MS-DOS (and early Windows versions) were originally adopted from CP/M.[93] The wildcard matching characters used by Windows (? and *) are based on those of CP/M,[94] as are the reserved filenames used to redirect output to a printer ("PRN:"), and the console ("CON:"). The drive names A and B were used to designate the two floppy disk drives that CP/M systems typically used; when hard drives appeared, they were designated C, which survived into MS-DOS as the C:\> command prompt.[95] The control character ^Z marking the end of some text files can also be attributed to CP/M.[96] Various commands in DOS were modelled after CP/M commands; some of them even carried the same name, like DIR, REN/RENAME, or TYPE (and ERA/ERASE in DR-DOS). File extensions like .TXT or .COM are still used to identify file types on many operating systems.

In 1997 and 1998, Caldera released some CP/M 2.2 binaries and source code under an open source license, also allowing the redistribution and modification of further collected Digital Research files related to the CP/M and MP/M families through Tim Olmstead's "The Unofficial CP/M Web site" since 1997.[97][98][99] After Olmstead's death on 12 September 2001,[100] the distribution license was refreshed and expanded by Lineo, who had meanwhile become the owner of those Digital Research assets, on 19 October 2001.[101][102][1][103] In October 2014, to mark the 40th anniversary of the first presentation of CP/M, the Computer History Museum released early source code versions of CP/M.[104]

As of 2018[update], there are a number of active vintage, hobby and retro-computer people and groups, and some small commercial businesses, still developing and supporting computer platforms that use CP/M (mostly 2.2) as the host operating system.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Amstrad CP/M Plus character set

- CPMulator

- CP/NET and CP/NOS

- Cromemco DOS, an operating system independently derived from CP/M

- Eagle Computer

- IMDOS

- List of machines running CP/M

- MP/M

- MP/NET and MP/NOS

- Multiuser DOS

- Pascal/MT+

- SpeedStart CP/M

- 86-DOS

- Kenbak-1

References

[edit]- ^ a b Gasperson, Tina (2001-11-26). "CP/M collection is back online with an Open Source licence - Walk down memory lane". The Register. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01.

- ^ a b Mann, Stephen (1983-08-15). "CP/M Plus, a third, updated version of CP/M". InfoWorld. Vol. 5, no. 33. p. 49. ISSN 0199-6649.

- ^ a b c Sandberg-Diment, Erik (1983-05-03). "Personal Computers: The Operating System in the middle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ a b c Markoff, John (1994-07-13). "Gary Kildall, 52, Crucial Player In Computer Development, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-10-03. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ a b Shustek, Len (2016-08-02). "In His Own Words: Gary Kildall". Remarkable People. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2016-12-17.

- ^ a b c Kildall, Gary Arlen (2016-08-02) [1993]. Kildall, Scott; Kildall, Kristin (eds.). Computer Connections: People, Places, and Events in the Evolution of the Personal Computer Industry (Manuscript, part 1). Kildall Family. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ^ Newton, Harry (2000). Newton's Telecom Dictionary. New York, New York, US: CMP Books. pp. 228. ISBN 1-57820-053-9.

- ^ Dahmke, Mark (1983-07-01). "CP/M Plus: The new disk operating system is faster and more efficient than CP/M". BYTE Magazine. Vol. 8, no. 7. p. 360.

- ^ Proven, Liam (2024-08-02). "50 years ago, CP/M started the microcomputer revolution". The Register.

- ^ "Compupro 8/16". old-computers.com. Archived from the original on 2016-01-03. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ^ Cole, Maggie (1981-05-25). "Gary Kildall and the Digital Research Success Story". InfoWorld. Vol. 3, no. 10. Palo Alto, California, US. pp. 52–53. ISSN 0199-6649. Archived from the original on 2024-07-01. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul (1982-07-05). "History of microcomputing, part 3: software genesis". InfoWorld. Vol. 4, no. 26. Palo Alto, California, US. p. 41. ISSN 0199-6649. Archived from the original on 2024-07-01. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- ^ Waite, Mitchell; Lafore, Robert W.; Volpe, Jerry (1982). The Official Book for the Commodore 128. H.W. Sams. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-67222456-0.

- ^ a b c d Kildall, Gary Arlen (January 1980). "The History of CP/M, The Evolution Of An Industry: One Person's Viewpoint". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Vol. 5, no. 1 #41. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original on 2016-11-24. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- ^ a b c d Kildall, Gary Arlen (June 1975), CP/M 1.1 or 1.2 BIOS and BDOS for Lawrence Livermore Laboratories

- ^ Johnson, Herbert R. (2009-01-04). "CP/M and Digital Research Inc. (DRI) History". www.retrotechnology.com. Archived from the original on 2008-08-20. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ Warren, Jim (April 1976). "First word on a floppy-disk operating system". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Vol. 1, no. 4. Menlo Park, California, US. p. 5. Subtitle: Command language & facilities similar to DECSYSTEM-10.

- ^ Digital Research (1978). CP/M. Pacific Grove, California, US: Digital Research. OCLC 221485970.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Bill (1981-10-19). "Software interchangeability problems in the 6502 marketplace". InfoWorld. 3 (22). IDG Publications: 16. Archived from the original on 2023-04-20. Retrieved 2023-04-19 – via Google Books.

- ^ Freiberger, Paul; Michael Swaine (2000). Fire in the Valley: The Making of the Personal Computer. McGraw-Hill. p. 175. ISBN 0071358927 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, David K.; Strutynski, Kathryn; Wharton, John Harrison (1983-05-14). "Tweaking more performance from an operating system - Hashing, caching, and memory blocking are just a few of the techniques used to punch up performance in the latest version of CP/M". System Design/Software. Computer Design - The Magazine of Computer Based Systems. Vol. 22, no. 6. Littleton, Massachusetts, US: PennWell Publications / PennWell Publishing Company. pp. 193–194, 196, 198, 200, 202, 204. ISSN 0010-4566. OCLC 1564597. CODEN CMPDA. ark:/13960/t3hz07m4t. Retrieved 2021-08-14. (7 pages)

- ^ a b "Kathryn Betty Strutynski". Monterey Herald (Obituary). 2010-06-19. Archived from the original on 2021-08-14. Retrieved 2021-08-10 – via Legacy.com.

- ^ a b Hogan, Thom (1981-09-14). "State of Microcomputing / Some Horses Running Neck and Neck". pp. 10–12. Archived from the original on 2024-06-24. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ Wise, Deborah (1982-05-10). "Mainframe makers court third-party vendors for micro software". InfoWorld. Vol. 4, no. 18. pp. 21–22. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2015-01-25.

- ^ a b Meyer, Edwin W. (1982-06-14). "The Xerox 820, a CP/M-operated system from Xerox". InfoWorld. Vol. 4, no. 23. pp. 101–104. Archived from the original on 2024-07-01. Retrieved 2019-03-30.

- ^ Hogan, Thom (1981-03-03). "Microsoft's Z80 SoftCard". InfoWorld. 3 (4). Popular Computing: 20–21. ISSN 0199-6649.

- ^ da Cruz, Frank (1984-04-27). "New release of KERMIT for CP/M-80". Info-CP/M (Mailing list). Kermit Project, Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Clarke, A.; Eaton, J. M.; David, D. Powys Lybbe (1983-10-26). CP/M - the Software Bus: A Programmer's Companion. Sigma Press. ISBN 978-0905104188.

- ^ Johnson, Herbert R. (2014-07-30). "CP/M and Digital Research Inc. (DRI) History". Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ Swaine, Michael (1997-04-01). "Gary Kildall and Collegial Entrepreneurship". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Archived from the original on 2007-01-24. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- ^ Bunnell, David (February 1982). "The Man Behind The Machine? / A PC Exclusive Interview With Software Guru Bill Gates". PC Magazine. Vol. 1, no. 1. pp. 16–23 [20]. Archived from the original on 2013-05-09. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- ^ a b Libes, Sol (June 1982). "Bytelines". BYTE. pp. 440–450. Retrieved 2025-03-17.

- ^ "Radio Shack Computer Catalog RSC-12 page 28". www.radioshackcomputercatalogs.com. Tandy/Radio Shack. Archived from the original on 2016-10-13. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ^ a b "Digital Research Has CP/M-86 for IBM Displaywriter" (PDF). Digital Research News - for Digital Research Users Everywhere. 1 (1). Pacific Grove, California, US: Digital Research, Inc.: 2, 5, 7. November 1981. Fourth Quarter. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ Maher, Jimmy (2017-07-31). "The complete history of the IBM PC, part two: The DOS empire strikes". Ars Technica. p. 3. Archived from the original on 2019-07-08. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ a b Kildall, Gary Arlen (1982-09-16). "Running 8-bit software on dual-processor computers" (PDF). Electronic Design: 157. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- ^ Snyder, John J. (June 1983). "A DEC on Every Desk?". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 6. pp. 104–106. Archived from the original on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2015-02-05.

- ^ "M 68 / M 68 MX". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06. Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- ^ Thomas, Rebecca A.; Yates, Jean L. (1981-05-11). "Books, Boards and Software for The New 16-Bit Processors". InfoWorld - The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community. Vol. 3, no. 9. Popular Computing, Inc. pp. 42–43. ISSN 0199-6649. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ Olmstead, Tim; Chaudry, Gabriele "Gaby". "Digital Research Source Code". Archived from the original on 2016-02-05.

- ^ Digital Research (1981): XLT86 - 8080 to 8086 Assembly Language Translator - User's Guide Archived 2016-11-18 at the Wayback Machine Digital Research Inc, Pacific Grove

- ^ a b Magid, Lawrence J. (June–July 1982). "Baby Blue". PC Magazine. Vol. 1, no. 3. p. 49. Archived from the original on 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2025-03-17.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (March 1984). "New Machines, Networks, and Sundry Software". BYTE. Vol. 9, no. 3. p. 46. Archived from the original on 2015-02-02. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ Isaacson, Walter (2014). The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution. Simon & Schuster. p. 358. ISBN 978-1-47670869-0.

- ^ Bellis, Mary. "Inventors of the Modern Computer Series - The History of the MS-DOS Operating Systems, Microsoft, Tim Paterson, and Gary Kildall". Archived from the original on 2012-04-27. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ^ Mace, Scott (1984-06-11). "CP/M Eludes Home Market". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 24. p. 46. Archived from the original on 2021-09-20. Retrieved 2021-09-20.

- ^ Groth, Nancy (1986-02-10). "Kaypro is retreating on CP/M". InfoWorld. Vol. 8, no. 6. p. 6. Archived from the original on 2022-03-20. Retrieved 2021-10-29.

- ^ "ZCPR - oldcomputers.ddns.org".

- ^ Markoff, John; Shapiro, Ezra (September 1984). "Z Whiz". BYTE West Coast. BYTE. pp. 396–397. Retrieved 2025-04-10.

- ^ "The Wonderful World of ZCPR3". 1987-11-30. Archived from the original on 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ "CP/M emulators for DOS". www.retroarchive.org/cpm. Luis Basto. Archived from the original on 2016-07-09. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ^ Davis, Randy (December 1985 – January 1986). Written at Greenville, Texas, US. "The New NEC Microprocessors - 8080, 8086, Or 8088?" (PDF). Micro Cornucopia. No. 27. Bend, Oregon, US: Micro Cornucopia Inc. pp. 4–7. ISSN 0747-587X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ^ "Plug-in CP/M coming". Personal Computer News. 1984-01-14. p. 7. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ Hetherington, Tony (February 1985). "Sharp MZ-800". Personal Computer World. pp. 144–146, 149–150. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ Coles, Ray (June 1984). "Cheaper, simpler CP/M" (PDF). Practical Computing. p. 43. Retrieved 2022-10-03.

- ^ "AMI releases specs on CP/M microchip". Microsystems. June 1984. p. 12. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ a b CP/M Operating System Manual (PDF). Digital Research. July 1982.

- ^ CP/M-86 System Guide (PDF). Digital Research. 1981.

- ^ CP/M-68K Operating System System Guide (PDF). Digital Research. January 1983.

- ^ CP/M-8000 Operating System System Guide (PDF). Digital Research. August 1984.

- ^ a b "CP/M Operating System Manual" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-12-14. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- ^ a b c CP/M Plus (CP/M Version 3) Operating System Programmers Guide (PDF) (2 ed.). Digital Research. April 1983 [January 1983]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-25. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ^ a b CP/M Plus (CP/M Version 3) Operating System User's Guide (PDF). Digital Research. 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-11-26. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ "PL/I Language Programmer's Guide" (PDF). Digital Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ Mace, Scott (1984-01-09). "IBM PC clone makers shun total compatibility". InfoWorld. Vol. 6, no. 2&3. pp. 79–81. Archived from the original on 2015-03-16. Retrieved 2015-02-04.

- ^ a b Derfler, Frank J. (1982-10-18). "Kaypro II—a low-priced, 26-pound portable micro". InfoWorld. p. 59. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (June 1983). "Zenith Z-100, Epson QX-10, Software Licensing, and the Software Piracy Problem". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 6. p. 411. Archived from the original on 2014-06-09. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ^ a b Arnow, Murray (1985). The Apple CP/M Book. Scott, Foresman and Company. pp. 2, 145. ISBN 0-673-18068-9. Retrieved 2025-06-25.

- ^ Loguidice, Bill (2012-07-28). "More on Avalon Hill Computer Games on Heath/Zenith platforms". Armchair Arcade. Archived from the original on 2015-07-23. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- ^ Sblendorio, Francesco (2015-12-01). "Gorillas for CP/M". GitHub. Archived from the original on 2016-02-05. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- ^ "Section 4 - CP/M Dynamic Debugging Tool". CP/M 2.2. Archived from the original on 2015-06-17. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ CP/M Dynamic Debugging Tool (DDT) - User's Guide (PDF). Digital Research. 1978 [1976]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-10-28. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ Shael (2010-06-26) [2009-12-09]. "DDT Utility". Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2014-08-29.

- ^ Brand, Stewart (1984). Whole Earth Software Catalog. Quantum Press/Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-38519166-1. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04.

- ^ Lieber, Eckhard; von Massenbach, Thomas (1987). "CP/M 2 lernt dazu. Modulare Systemerweiterungen auch für das 'alte' CP/M". c't - magazin für computertechnik (part 1) (in German). Vol. 1987, no. 1. Heise Verlag. pp. 124–135.

- ^ Lieber, Eckhard; von Massenbach, Thomas (1987). "CP/M 2 lernt dazu. Modulare Systemerweiterungen auch für das 'alte' CP/M". c't - magazin für computertechnik (part 2) (in German). Vol. 1987, no. 2. Heise Verlag. pp. 78–85.

- ^ Huck, Alex (2016-10-09). "RSM für CP/M 2.2". Homecompuer DDR (in German). Archived from the original on 2016-11-25. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- ^ Pournelle, Jerry (April 1982). "The Osborne 1, Zeke's New Friends, and Spelling Revisited". BYTE. Vol. 7, no. 4. p. 212. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

- ^ a b Pournelle, Jerry (September 1982). "Letters, Pascal, CB/80, and Cardfile". BYTE. pp. 318–341. Retrieved 2024-12-30.

- ^ Waite, Mitchell; Lafore, Robert W.; Volpe, Jerry (1985). "The CP/M Mode". The Official Book for the Commodore 128 Personal Computer. Howard W. Sams & Co. p. 98. ISBN 0-672-22456-9.

- ^ Fager, Roger; Bohr, John (September 1983). "The Kaypro II". BYTE. Vol. 8, no. 9. p. 212. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- ^ "Now: A Complete CP/M Pascal for Only $29.95!". BYTE (advertisement). Vol. 7, no. 12. December 1982. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2016-07-21. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- ^ "Ellis Computing". BYTE (advertisement). Vol. 8, no. 12. December 1983. p. 69.

- ^ "Distribution I: Software" (PDF). The Rosen Electronics Letter. 1983-02-22. pp. 6–11. Retrieved 2025-06-05.

- ^ Johnson-Laird, Andy (1983). "3". The programmer's CP/M handbook. Berkeley, California, US: Osborne/McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-88134-103-7.

- ^ "Old-computers.com: The Museum". Archived from the original on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ Ciarcia, Steve (September 1985). "Build the SB-180" (PDF). BYTE Magazine. CMP Media. p. 100. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-11-29. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ CP/AM 5.1 User Manual. Applied Engineering. p. 1. Retrieved 2020-05-22.

- ^ "CP/M Builtin Commands". discordia.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-04-12. Retrieved 2009-01-28.

- ^ a b Pohlers, Volker (2019-04-30). "CP/A". Homecomputer DDR (in German). Archived from the original on 2020-02-21. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ a b Kurth, Rüdiger; Groß, Martin; Hunger, Henry (2019-01-03). "Betriebssysteme". www.robotrontechnik.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ a b c Kurth, Rüdiger; Groß, Martin; Hunger, Henry (2019-01-03). "Betriebssystem SCP". www.robotrontechnik.de (in German). Archived from the original on 2019-04-27. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (2009-06-10). "Why does MS-DOS use 8.3 filenames instead of, say, 11.2 or 16.16?". The Old New Thing. Archived from the original on 2011-09-22. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (2007-12-17). "How did wildcards work in MS-DOS?". The Old New Thing. Archived from the original on 2011-05-08. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (2003-10-22). "What's the deal with those reserved filenames like NUL and CON?". The Old New Thing. Archived from the original on 2010-08-02. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Chen, Raymond (2004-03-16). "Why do text files end in Ctrl+Z?". The Old New Thing. Archived from the original on 2011-02-06. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- ^ Olmstead, Tim (1997-08-10). "CP/M Web site needs a host". Newsgroup: comp.os.cpm. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ Olmstead, Tim (1997-08-29). "ANNOUNCE: Caldera CP/M site is now up". Newsgroup: comp.os.cpm. Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-09. [1]

- ^ "License Agreement". Caldera, Inc. 1997-08-28. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2015-07-25. [2][dead link] [3][permanent dead link]

- ^ "Tim Olmstead". 2001-09-12. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09.

- ^ Sparks, Bryan Wayne (2001-10-19). Chaudry, Gabriele "Gaby" (ed.). "License agreement for the CP/M material presented on this site". Lineo, Inc. Archived from the original on 2018-09-08. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

- ^ Chaudry, Gabriele "Gaby" (ed.). "The Unofficial CP/M Web Site". Archived from the original on 2016-02-03.

- ^ Swaine, Michael (2004-06-01). "CP/M and DRM". Dr. Dobb's Journal. Vol. 29, no. 6. CMP Media LLC. pp. 71–73. #361. Archived from the original on 2018-09-09. Retrieved 2018-09-09. [4] Archived 2024-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laws, David (2014-10-01). "Early Digital Research CP/M Source Code". Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2015-07-25.

Further reading

[edit]- Zaks, Rodnay (1980). The CP/M Handbook With MP/M. SYBEX Inc. ISBN 0-89588-048-2.

- Conn, Richard (1985). ZCPR3 - The Manual. New York Zoetrope. ISBN 0-918432-59-6.

- "Z-System Corner: Tenth Anniversary of ZCPR". The Computer Journal (54). Archived from the original on 2010-10-29.

- "The origin of CP/M's name". Archived from the original on 2008-06-11.

- Katie, Mustafa A. (2013-08-14). "Intel iPDS-100 Using CP/M-Video". Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- "IEEE Milestone in Electrical Engineering and Computing - CP/M - Microcomputer Operating System, 1974" (PDF). Computer History Museum. 2014-04-25. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- "Triumph of the Nerds". PBS. (NB. This PBS series includes the details of IBM's choice of Microsoft DOS over Digital Research's CP/M for the IBM PC)

- "CP/M FAQ". comp.os.cpm. [5]

External links

[edit]- The Unofficial CP/M Web site (founded by Tim Olmstead) - Includes source code

- Gaby Chaudry's Homepage for CP/M and Computer History - includes ZCPR materials

- CP/M Main Page - John C. Elliott's technical information site

- MaxFrame's Digital Research CP/M page