Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

SS Imo

View on Wikipedia

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator | 1889: White Star Line |

| Port of registry |

|

| Builder | Harland & Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 211 |

| Launched | 1 January 1889 |

| Completed | 16 February 1889 |

| Maiden voyage | 21 February 1889 |

| Refit | 1912 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Wrecked 30 November 1921 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type |

|

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 430.7 ft (131.3 m) |

| Beam | 45.2 ft (13.8 m) |

| Depth | 30.0 ft (9.1 m) |

| Installed power | 424 NHP |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Capacity | 1889: 1,000 cattle, 48 passengers |

| Crew | 40 |

SS Imo[1] was a merchant steamship that was built in 1889 to carry livestock and passengers, and converted in 1912 into a whaling factory ship. She was built as Runic, renamed Tampican in 1895, Imo in 1912 and Guvernøren (The Governor) in 1920.

In 1917 the Belgian Relief Commission chartered Imo to take humanitarian supplies to German-occupied Belgium. On 6 December 1917 she was involved in a collision in Halifax Harbour with the French cargo ship Mont-Blanc, which was carrying munitions. The resultant fire aboard Mont Blanc caused the historic and catastrophic Halifax Explosion, which levelled the Richmond District in the North End of the city. Although Imo's superstructure was severely damaged by the blast, the ship was repaired and returned to service in 1918.

The ship was renamed Guvernøren (The Governor) in 1920. On 30 November 1921 she ran aground off East Falkland [28] and was abandoned.

Building and owners

[edit]Harland & Wolff built the ship in Belfast as yard number 211. She was launched on 1 January 1889 and completed on 16 February. She was designed to carry 1,000 head of live cattle, plus she had berths for 48 passengers.[2] As built, her tonnages were 4,649 GRT and 3,046 NRT.[3]

Her first owner was the Oceanic Steam Navigation Co, which was part of White Star Line. She was registered at Liverpool. Her United Kingdom official number was 93837 and her code letters were LBPW.[3] In May 1895 the West Indies and Pacific Steamship Line acquired the ship and renamed her Tampican. On 31 December 1899 she was transferred with the rest of the company's fleet to Frederick Leyland & Co.[4]

In 1912 HE Moss acquired Tampican, but in the same year he sold her on to the Southern Pacific Whaling Company, who had her refitted as a whaling factory ship.[4] This changed her tonnages to 5,043 GRT and 3,161 NRT. She was renamed Imo and registered in Christiania (now Oslo), Norway. Her code letters were changed to MJGB.[5]

Halifax Explosion

[edit]In 1917 Imo sailed as a charter for the Belgian Relief Commission. Being neutral, Imo had on her side the words "Belgian Relief" to protect her from German and Austro-Hungarian submarines.[6] Imo was sailing in ballast (empty) en route to New York to load relief supplies. She reached Halifax on 3 December for neutral inspection, and spent two days in Bedford Basin awaiting bunkering.[7] She was cleared to leave port on 5 December, but was delayed as her bunker coal did not arrive until late that afternoon. Bunkering was not completed until after the anti-submarine nets had been raised for the night, so she could not weigh anchor until the next morning.[8][9]

Imo had a crew of 39 men, commanded by Captain Haakon From. With a registered length of 430.7 ft (131.3 m) but a beam of only 45.2 ft (13.8 m), Imo was long and narrow. Because she was in ballast (without cargo), her propeller and rudder were nearly out of the water, making her hard to steer. She was powered by a triple-expansion steam engine with a single 20-foot right-hand propeller, able to make 60 revolutions per minute. Her propeller gave her a "transverse thrust", i.e. while making headway she veered to the left, in reverse she swung to the right. Under these conditions, Imo was at a disadvantage in navigating in tight quarters. "Due to the combined effect of transverse thrust and the length, and depth of SS Imo's hull, and its keel, she was difficult to maneuver".[6]

The guard ship HMCS Acadia signalled Imo clearance to leave Bedford Basin at about 7:30 a.m. on the morning of 6 December,[10] with Pilot William Hayes aboard. Imo entered the Narrows well above the harbour's speed limit, in an attempt to make up for the delay from bunkering.[7] Imo met a US tramp steamer, SS Clara, being piloted up the wrong (western) side of the harbour.[11] The pilots agreed to pass starboard to starboard.[12] Soon afterwards, Imo was forced to head even further towards the Dartmouth shore after passing the tugboat Stella Maris, which was travelling up the harbour to Bedford Basin near mid-channel. Horatio Brannen, captain of Stella Maris, saw Imo approaching at excessive speed and ordered his ship closer to the western shore to avoid an accident.[13][14][15]

This incident forced Imo even further over towards the Dartmouth side of the harbour into the path of the oncoming Mont-Blanc, a French cargo ship fully loaded with a highly volatile cargo of wartime explosives. Unable to ground his ship for fear of a shock that would set off his explosive cargo, Pilot Francis Mackey ordered Mont-Blanc to steer hard to port (starboard helm) and crossed the Norwegian ship's bows in a last-second bid to avoid a collision. The two ships were almost parallel to each other, when Imo suddenly sent out three signal blasts, indicating she was reversing her engine. The combination of the cargoless ship's height in the water and the transverse thrust of her right-hand propeller caused the ship's head to swing into Mont-Blanc.[16][7] At 8:45 a.m., the two ships collided at slow speed in The Narrows of Halifax Harbour.[17]

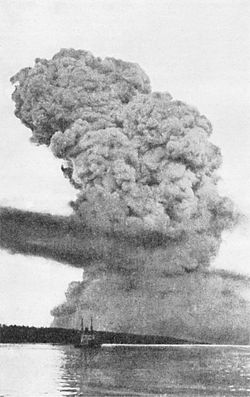

While the damage to Mont Blanc was not severe, it toppled barrels that broke open and flooded the deck with benzol that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo's engine engaged, she quickly disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc's hull. These ignited the vapour from the benzol. A fire started at the waterline and travelled quickly up the side of the ship as the benzol spewed out from crushed drums on Mont-Blanc's decks. The fire quickly became uncontrollable. Surrounded by thick black smoke, and fearing she would explode almost immediately, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship.[18][17] At 9:04:35 a.m., the out-of-control fire aboard Mont-Blanc finally set off her highly explosive cargo.[19] The ship was completely blown apart and a powerful blast wave radiated away from the explosion at more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) per second. Temperatures of 5,000 °C (9,030 °F) and pressures of thousands of atmospheres accompanied the moment of detonation at the centre of the explosion.[20][7]

About 1,950 people were killed by debris, fires, or collapsed buildings, and it is estimated that more than 9,000 people were injured.[21] The explosion wrecked the upper decks of Imo. Three of the four personnel on her open bridge were killed: Captain From, Pilot William Hayes and R. Albert Ingvald Iverson, the First Officer. John Johansen, the helmsman, was severely injured but survived. Four other crewmen were also killed: Harold Iverson (seaman), Oscar Kallstrom (fireman), Johannes C. Kersenboom (carpenter) and Gustav Petersen (boatswain).[22] The blast and the tsunami that followed threw the ship ashore on the Dartmouth side of Halifax Harbour.[23]

The Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry carried out the official investigation into the cause of the collision. Charles Jost Burchell, a prominent Halifax lawyer, represented Imo's owners as he did in the lengthy civil litigation. The inquiry initially held Imo's crew blameless, and put the entire responsibility for the collision on the Mont-Blanc. However following appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada in May 1919 and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on 22 March 1920, both ships were found to have made navigational errors and were found equally at fault for the collision and its consequences.[24][25]

Later career

[edit]Imo was refloated 26 April 1918, repaired and returned to service. Renamed Guvernøren ("The Governor") in 1920, she was a whale oil tanker until 30 November 1921, when the man at the helm collapsed drunk after celebratory drinking, leaving nobody at the wheel. The ship ran aground on rocks at Cow Bay two miles off Cape Carysfort about 20 miles from Port Stanley on East Falkland.[26] No crew were lost. Salvage attempts were halted on 3 December and the ship was abandoned to the sea.[27][28]

Stamp and commemoration

[edit]In 2005 the Falkland Islands issued a postage stamp showing Guvernøren.[29] The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, Nova Scotia has an exhibit about the ship's role in the Halifax Explosion, which also displays some fittings from Imo including a dog collar from the ship's mascot.

On 6 November 2017, Canada Post issued a stamp commemorating the devastating explosion. Released one month before the blast's centenary, the issue also salutes the resilience of the Haligonians who rebuilt their city from the ashes.[citation needed]

The stamp captures the moments before and after the disaster through elements from the past and present. Local illustrator Mike Little and historical consultant Joel Zemel (who also wrote the descriptive text)[30] recreated the scene based on archived historical materials including witness accounts from the inquiry. Because the ships' plans were not available at the time, three extant photographs of SS Mont-Blanc,[circular reference] and several available images of Imo were used as the main references. An image of the front page of The Halifax Herald the day after the explosion shows the heartbreaking aftermath. The stamp was designed by Larry Burke and Anna Stredulinsky of Burke & Burke in Halifax.[31]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The ship had been named with the initials – JMO – after the senior owner of the company, Johan Martin Osmundsen (aka Jurgens M. Osmond), but people started calling her Imo and the name stuck. Source: Methods of Disaster Research by Robert A. Stallings (International Research Committee on Disasters ©2002), pp. 281–282.

- ^ "Runic". Harland & Wolff Shipbuilding & EngineeringWorks. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ a b Mercantile Navy List. London. 1890. p. 216. Retrieved 15 September 2022 – via Crew List Index Project.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Runic". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1914, IMB–IMP.

- ^ a b "The Collision". The Halifax Explosion. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d Lilley, Steve (January 2013). "Kiloton killer". System Failure Case Study. 7 (1). NASA.

- ^ Kitz & Payzant 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Flemming 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Conlin, Dan (6 December 2013). "The Harbour Remembers the Halifax Explosion". Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

- ^ Flemming 2004, p. 23.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Flemming 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Kitz & Payzant 2006, p. 17.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 33.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Flemming 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Kitz 1989, p. 19.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Ruffman & Howell 1994, p. 277.

- ^ CBC – Halifax Explosion 1917

- ^ "Halifax Explosion Remembrance Book" (Nova Scotia Archives website)

- ^ "Imo-1917" Archived 27 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, On the Rocks Shipwreck Database, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

- ^ Zemel 2016, pp. 88–277.

- ^ "Halifax Explosion Infosheet", Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Halifax. Archived 21 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lorton, Roger (2012). The Falkland Island History.[clarification needed]

- ^ "Falkland Stamps!". Falklands Philatelic Bureau. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ "American Marine Engineer Masy, 1918". National Marine Engineers Beneficial Association of the United States. Retrieved 14 September 2020 – via Haithi Trust.

- ^ aukepalmhof (24 November 2009). "IMO/GUVERNOREN and MONT BLANC". shipstamps.co.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ^ Canada Post Corporation's OFDC issue and booklet credits.

- ^ Canada Post

Bibliography

[edit]- Flemming, David (2004). Explosion in Halifax Harbour. Formac. ISBN 978-0-88780-632-2.

- Kitz, Janet (1989). Shattered City: The Halifax Explosion and the Road to Recovery. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-921054-30-6.

- Kitz, Janet; Payzant, Joan (2006). December 1917: Revisiting the Halifax Explosion. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55109-566-0.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914.

- MacDonald, Laura (2005). Curse of the Narrows: The Halifax Explosion of 1917. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-200787-0.

- Ruffman, Alan; Howell, Colin D., eds. (1994). Ground Zero: A Reassessment of the 1917 Explosion in Halifax Harbour. Nimbus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55109-095-5.

- Zemel, Joel (2016). Scapegoat, the extraordinary legal proceedings following the 1917 Halifax Explosion (2nd ed.). New World Publishing. ISBN 978-1-895814-62-0.

External links

[edit]- "SS Guvernøren (Ex-Imo) [+1921]". Wrecksite.

- HalifaxExplosion.net features images and reading material related to the Halifax Explosion and the early RCN.