Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

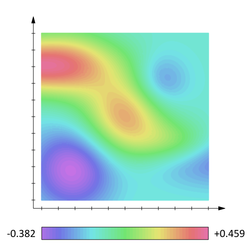

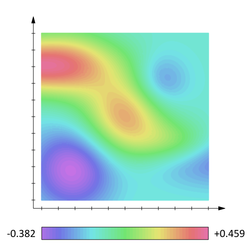

Scalar field

View on Wikipedia

In mathematics and physics, a scalar field is a function associating a single[dubious – discuss] number to each point in a region of space – possibly physical space. The scalar may either be a pure mathematical number (dimensionless) or a scalar physical quantity (with units).

In a physical context, scalar fields are required to be independent of the choice of reference frame. That is, any two observers using the same units will agree on the value of the scalar field at the same absolute point in space (or spacetime) regardless of their respective points of origin. Examples used in physics include the temperature distribution throughout space, the pressure distribution in a fluid, and spin-zero quantum fields, such as the Higgs field. These fields are the subject of scalar field theory.

Definition

[edit]Mathematically, a scalar field on a region U is a real or complex-valued function or distribution on U.[1][2] The region U may be a set in some Euclidean space, Minkowski space, or more generally a subset of a manifold, and it is typical in mathematics to impose further conditions on the field, such that it be continuous or often continuously differentiable to some order. A scalar field is a tensor field of order zero,[3] and the term "scalar field" may be used to distinguish a function of this kind with a more general tensor field, density, or differential form.

Physically, a scalar field is additionally distinguished by having units of measurement associated with it. In this context, a scalar field should also be independent of the coordinate system used to describe the physical system—that is, any two observers using the same units must agree on the numerical value of a scalar field at any given point of physical space. Scalar fields are contrasted with other physical quantities such as vector fields, which associate a vector to every point of a region, as well as tensor fields and spinor fields.[citation needed] More subtly, scalar fields are often contrasted with pseudoscalar fields.

Uses in physics

[edit]In physics, scalar fields often describe the potential energy associated with a particular force. The force is a vector field, which can be obtained as a factor of the gradient of the potential energy scalar field. Examples include:

- Potential fields, such as the Newtonian gravitational potential, or the electric potential in electrostatics, are scalar fields which describe the more familiar forces.

- A temperature, humidity, or pressure field, such as those used in meteorology.

Examples in quantum theory and relativity

[edit]- In quantum field theory, a scalar field is associated with spin-0 particles. The scalar field may be real or complex valued. Complex scalar fields represent charged particles. These include the Higgs field of the Standard Model, as well as the charged pions mediating the strong nuclear interaction.[4]

- In the Standard Model of elementary particles, a scalar Higgs field is used to give the leptons and massive vector bosons their mass, via a combination of the Yukawa interaction and the spontaneous symmetry breaking. This mechanism is known as the Higgs mechanism.[5] A candidate for the Higgs boson was first detected at CERN in 2012.

- In scalar theories of gravitation scalar fields are used to describe the gravitational field.

- Scalar–tensor theories represent the gravitational interaction through both a tensor and a scalar. Such attempts are for example the Jordan theory[6] as a generalization of the Kaluza–Klein theory and the Brans–Dicke theory.[7]

- Scalar fields like the Higgs field can be found within scalar–tensor theories, using as scalar field the Higgs field of the Standard Model.[8][9] This field interacts gravitationally and Yukawa-like (short-ranged) with the particles that get mass through it.[10]

- Scalar fields are found within superstring theories as dilaton fields, breaking the conformal symmetry of the string, though balancing the quantum anomalies of this tensor.[11]

- Scalar fields are hypothesized to have caused the high accelerated expansion of the early universe (inflation),[12] helping to solve the horizon problem and giving a hypothetical reason for the non-vanishing cosmological constant of cosmology. Massless (i.e. long-ranged) scalar fields in this context are known as inflatons. Massive (i.e. short-ranged) scalar fields are proposed, too, using for example Higgs-like fields.[13]

Other kinds of fields

[edit]- Vector fields, which associate a vector to every point in space. Some examples of vector fields include the air flow (wind) in meteorology.

- Tensor fields, which associate a tensor to every point in space. For example, in general relativity gravitation is associated with the tensor field called Einstein tensor. In Kaluza–Klein theory, spacetime is extended to five dimensions and its Riemann curvature tensor can be separated out into ordinary four-dimensional gravitation plus an extra set, which is equivalent to Maxwell's equations for the electromagnetic field, plus an extra scalar field known as the "dilaton".[citation needed] (The dilaton scalar is also found among the massless bosonic fields in string theory.)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Apostol, Tom (1969). Calculus. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- ^ "Scalar", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- ^ "Scalar field", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- ^ Technically, pions are actually examples of pseudoscalar mesons, which fail to be invariant under spatial inversion, but are otherwise invariant under Lorentz transformations.

- ^ P.W. Higgs (Oct 1964). "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons". Phys. Rev. Lett. 13 (16): 508–509. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..508H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508.

- ^ Jordan, P. (1955). Schwerkraft und Weltall. Braunschweig: Vieweg.

- ^ Brans, C.; Dicke, R. (1961). "Mach's Principle and a Relativistic Theory of Gravitation". Phys. Rev. 124 (3): 925. Bibcode:1961PhRv..124..925B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.124.925.

- ^ Zee, A. (1979). "Broken-Symmetric Theory of Gravity". Phys. Rev. Lett. 42 (7): 417–421. Bibcode:1979PhRvL..42..417Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.42.417.

- ^ Dehnen, H.; Frommert, H.; Ghaboussi, F. (1992). "Higgs field and a new scalar–tensor theory of gravity". Int. J. Theor. Phys. 31 (1): 109. Bibcode:1992IJTP...31..109D. doi:10.1007/BF00674344. S2CID 121308053.

- ^ Dehnen, H.; Frommmert, H. (1991). "Higgs-field gravity within the standard model". Int. J. Theor. Phys. 30 (7): 985–998 [p. 987]. Bibcode:1991IJTP...30..985D. doi:10.1007/BF00673991. S2CID 120164928.

- ^ Brans, C. H. (2005). "The Roots of scalar–tensor theory". arXiv:gr-qc/0506063.

- ^ Guth, A. (1981). "Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems". Phys. Rev. D. 23 (2): 347–356. Bibcode:1981PhRvD..23..347G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.347.

- ^ Cervantes-Cota, J. L.; Dehnen, H. (1995). "Induced gravity inflation in the SU(5) GUT". Phys. Rev. D. 51 (2): 395–404. arXiv:astro-ph/9412032. Bibcode:1995PhRvD..51..395C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.51.395. PMID 10018493. S2CID 11077875.