Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear force

View on Wikipedia| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

The nuclear force (or nucleon–nucleon interaction, residual strong force, or, historically, strong nuclear force) is a force that acts between hadrons, most commonly observed between protons and neutrons of atoms. Neutrons and protons, both nucleons, are affected by the nuclear force almost identically. Since protons have charge +1 e, they experience an electric force that tends to push them apart, but at short range the attractive nuclear force is strong enough to overcome the electrostatic force. The nuclear force binds nucleons into atomic nuclei.

The nuclear force is powerfully attractive between nucleons at distances of about 0.8 femtometre (fm, or 0.8×10−15 m), but it rapidly decreases to insignificance at distances beyond about 2.5 fm. At distances less than 0.7 fm, the nuclear force becomes repulsive. This repulsion is responsible for the size of nuclei, since nucleons can come no closer than the force allows. (The size of an atom, of size in the order of angstroms (Å, or 10−10 m), is five orders of magnitude larger.) The nuclear force is not simple, though, as it depends on the nucleon spins, has a tensor component, and may depend on the relative momentum of the nucleons.[2]

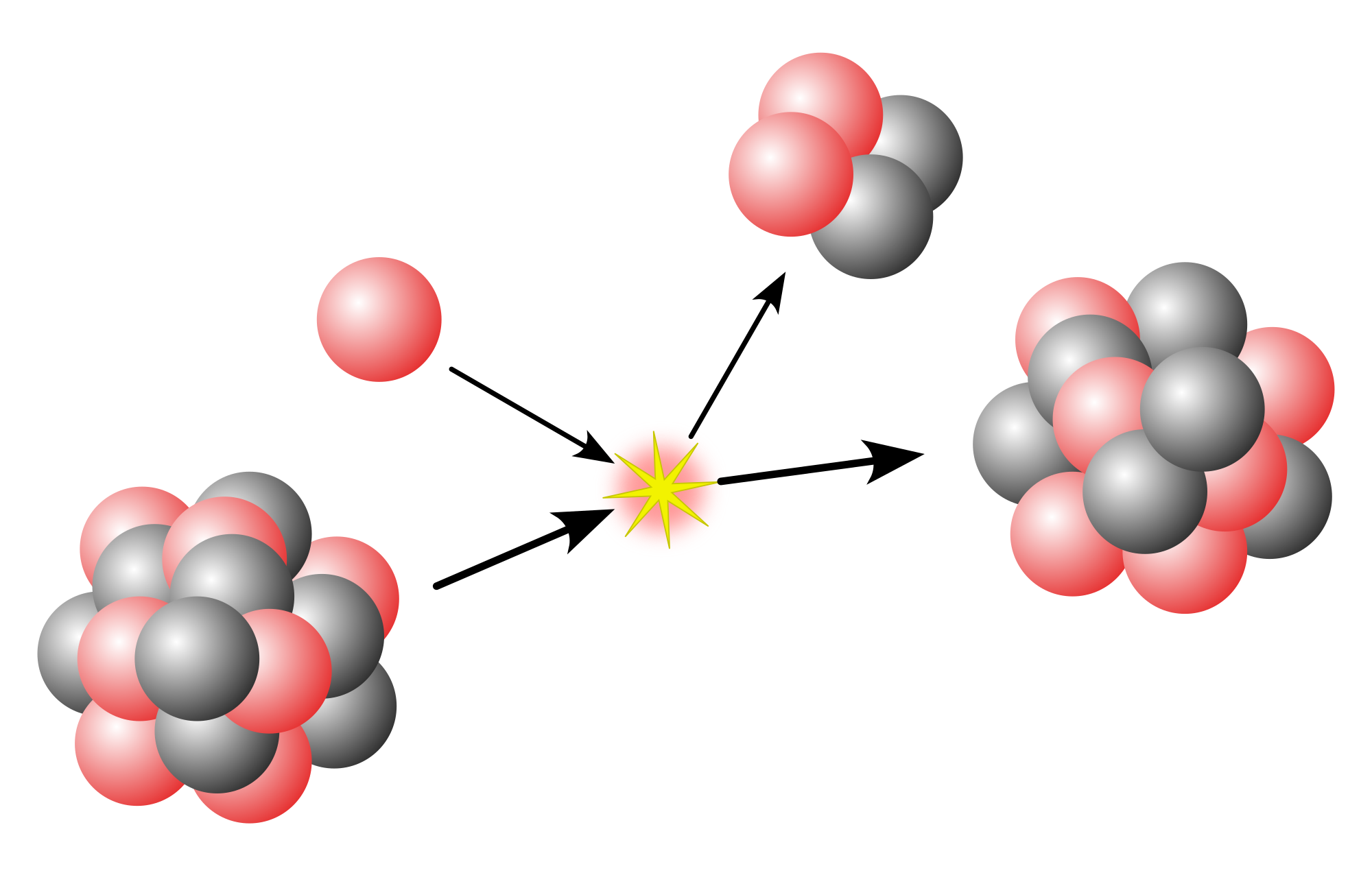

The nuclear force has an essential role in storing energy that is used in nuclear power and nuclear weapons. Work (energy) is required to bring charged protons together against their electric repulsion. This energy is stored when the protons and neutrons are bound together by the nuclear force to form a nucleus. The mass of a nucleus is less than the sum total of the individual masses of the protons and neutrons. The difference in masses is known as the mass defect, which can be expressed as an energy equivalent. Energy is released when a heavy nucleus breaks apart into two or more lighter nuclei. This energy is the internucleon potential energy that is released when the nuclear force no longer holds the charged nuclear fragments together.[3][4]

A quantitative description of the nuclear force relies on equations that are partly empirical. These equations model the internucleon potential energies, or potentials. (Generally, forces within a system of particles can be more simply modelled by describing the system's potential energy; the negative gradient of a potential is equal to the vector force.) The constants for the equations are phenomenological, that is, determined by fitting the equations to experimental data. The internucleon potentials attempt to describe the properties of nucleon–nucleon interaction. Once determined, any given potential can be used in, e.g., the Schrödinger equation to determine the quantum mechanical properties of the nucleon system.

The discovery of the neutron in 1932 revealed that atomic nuclei were made of protons and neutrons, held together by an attractive force. By 1935 the nuclear force was conceived to be transmitted by particles called mesons. This theoretical development included a description of the Yukawa potential, an early example of a nuclear potential. Pions, fulfilling the prediction, were discovered experimentally in 1947. By the 1970s, the quark model had been developed, by which the mesons and nucleons were viewed as composed of quarks and gluons. By this new model, the nuclear force, resulting from the exchange of mesons between neighbouring nucleons, is a multiparticle interaction, the collective effect of strong force on the underlining structure of the nucleons.

Description

[edit]

While the nuclear force is usually associated with nucleons, more generally this force is felt between hadrons, or particles composed of quarks. At small separations between nucleons (less than ~ 0.7 fm between their centres, depending upon spin alignment) the force becomes repulsive, which keeps the nucleons at a certain average separation. For identical nucleons (such as two neutrons or two protons) this repulsion arises from the Pauli exclusion force. A Pauli repulsion also occurs between quarks of the same flavour from different nucleons (a proton and a neutron).

Field strength

[edit]At distances larger than 0.7 fm the force becomes attractive between spin-aligned nucleons, becoming maximal at a centre–centre distance of about 0.9 fm. Beyond this distance the force drops exponentially, until beyond about 2.0 fm separation, the force is negligible. Nucleons have a radius of about 0.8 fm.[5]

At short distances (less than 1.7 fm or so), the attractive nuclear force is stronger than the repulsive Coulomb force between protons; it thus overcomes the repulsion of protons within the nucleus. However, the Coulomb force between protons has a much greater range as it varies as the inverse square of the charge separation, and Coulomb repulsion thus becomes the only significant force between protons when their separation exceeds about 2 to 2.5 fm.

The nuclear force has a spin-dependent component. The force is stronger for particles with their spins aligned than for those with their spins anti-aligned. If two particles are the same, such as two neutrons or two protons, the force is not enough to bind the particles, since the spin vectors of two particles of the same type must point in opposite directions when the particles are near each other and are (save for spin) in the same quantum state. This requirement for fermions stems from the Pauli exclusion principle. For fermion particles of different types, such as a proton and neutron, particles may be close to each other and have aligned spins without violating the Pauli exclusion principle, and the nuclear force may bind them (in this case, into a deuteron), since the nuclear force is much stronger for spin-aligned particles. But if the particles' spins are anti-aligned, the nuclear force is too weak to bind them, even if they are of different types.

The nuclear force also has a tensor component which depends on the interaction between the nucleon spins and the angular momentum of the nucleons, leading to deformation from a simple spherical shape.

Nuclear binding

[edit]To disassemble a nucleus into unbound protons and neutrons requires work against the nuclear force. Conversely, energy is released when a nucleus is created from free nucleons or other nuclei: the nuclear binding energy. Because of mass–energy equivalence (i.e. Einstein's formula E = mc2), releasing this energy causes the mass of the nucleus to be lower than the total mass of the individual nucleons, leading to the so-called "mass defect".[6]

The nuclear force is nearly independent of whether the nucleons are neutrons or protons. This property is called charge independence. The force depends on whether the spins of the nucleons are parallel or antiparallel, as it has a non-central or tensor component. This part of the force does not conserve orbital angular momentum, which under the action of central forces is conserved.

The symmetry resulting in the strong force, proposed by Werner Heisenberg, is that protons and neutrons are identical in every respect, other than their charge. This is not completely true, because neutrons are a tiny bit heavier, but it is an approximate symmetry. Protons and neutrons are therefore viewed as the same particle, but with different isospin quantum numbers; conventionally, the proton is isospin up, while the neutron is isospin down. The strong force is invariant under SU(2) isospin transformations, just as other interactions between particles are invariant under SU(2) transformations of intrinsic spin. In other words, both isospin and intrinsic spin transformations are isomorphic to the SU(2) symmetry group. There are only strong attractions when the total isospin of the set of interacting particles is 0, which is confirmed by experiment.[7]

Our understanding of the nuclear force is obtained by scattering experiments and the binding energy of light nuclei.

The nuclear force occurs by the exchange of virtual light mesons, such as the virtual pions, as well as two types of virtual mesons with spin (vector mesons), the rho mesons and the omega mesons. The vector mesons account for the spin-dependence of the nuclear force in this "virtual meson" picture.

The nuclear force is distinct from what historically was known as the weak nuclear force. The weak interaction is one of the four fundamental interactions, and plays a role in processes such as beta decay. The weak force plays no role in the interaction of nucleons, though it is responsible for the decay of neutrons to protons and vice versa.

History

[edit]The nuclear force has been at the heart of nuclear physics ever since the field was born in 1932 with the discovery of the neutron by James Chadwick. The traditional goal of nuclear physics is to understand the properties of atomic nuclei in terms of the "bare" interaction between pairs of nucleons, or nucleon–nucleon forces (NN forces).

Within months after the discovery of the neutron, Werner Heisenberg[8][9][10] and Dmitri Ivanenko[11] had proposed proton–neutron models for the nucleus.[12] Heisenberg approached the description of protons and neutrons in the nucleus through quantum mechanics, an approach that was not at all obvious at the time. Heisenberg's theory for protons and neutrons in the nucleus was a "major step toward understanding the nucleus as a quantum mechanical system".[13] Heisenberg introduced the first theory of nuclear exchange forces that bind the nucleons. He considered protons and neutrons to be different quantum states of the same particle, i.e., nucleons distinguished by the value of their nuclear isospin quantum numbers.

One of the earliest models for the nucleus was the liquid-drop model developed in the 1930s. One property of nuclei is that the average binding energy per nucleon is approximately the same for all stable nuclei, which is similar to a liquid drop. The liquid-drop model treated the nucleus as a drop of incompressible nuclear fluid, with nucleons behaving like molecules in a liquid. The model was first proposed by George Gamow and then developed by Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg, and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. This crude model did not explain all the properties of the nucleus, but it did explain the spherical shape of most nuclei. The model also gave good predictions for the binding energy of nuclei.

In 1934, Hideki Yukawa made the earliest attempt to explain the nature of the nuclear force. According to his theory, massive bosons (mesons) mediate the interaction between two nucleons. In light of quantum chromodynamics (QCD)—and, by extension, the Standard Model—meson theory is no longer perceived as fundamental. But the meson-exchange concept (where hadrons are treated as elementary particles) continues to represent the best working model for a quantitative NN potential. The Yukawa potential (also called a screened Coulomb potential) is a potential of the form where g is a magnitude scaling constant, i.e., the amplitude of potential, is the Yukawa particle mass, r is the radial distance to the particle. The potential is monotone increasing, implying that the force is always attractive. The constants are determined empirically. The Yukawa potential depends only on the distance r between particles, hence it models a central force.

Throughout the 1930s a group at Columbia University led by I. I. Rabi developed magnetic-resonance techniques to determine the magnetic moments of nuclei. These measurements led to the discovery in 1939 that the deuteron also possessed an electric quadrupole moment.[14][15] This electrical property of the deuteron had been interfering with the measurements by the Rabi group. The deuteron, composed of a proton and a neutron, is one of the simplest nuclear systems. The discovery meant that the physical shape of the deuteron was not symmetric, which provided valuable insight into the nature of the nuclear force binding nucleons. In particular, the result showed that the nuclear force was not a central force, but had a tensor character.[1] Hans Bethe identified the discovery of the deuteron's quadrupole moment as one of the important events during the formative years of nuclear physics.[14]

Historically, the task of describing the nuclear force phenomenologically was formidable. The first semi-empirical quantitative models came in the mid-1950s,[1] such as the Woods–Saxon potential (1954). There was substantial progress in experiment and theory related to the nuclear force in the 1960s and 1970s. One influential model was the Reid potential (1968)[1] where and where the potential is given in units of MeV. In recent years,[when?] experimenters have concentrated on the subtleties of the nuclear force, such as its charge dependence, the precise value of the πNN coupling constant, improved phase-shift analysis, high-precision NN data, high-precision NN potentials, NN scattering at intermediate and high energies, and attempts to derive the nuclear force from QCD.[citation needed]

As a residual of strong force

[edit]

The nuclear force is a residual effect of the more fundamental strong force, or strong interaction. The strong interaction is the attractive force that binds the elementary particles called quarks together to form the nucleons (protons and neutrons) themselves. This more powerful force, one of the fundamental forces of nature, is mediated by particles called gluons. Gluons hold quarks together through colour charge which is analogous to electric charge, but far stronger. Quarks, gluons, and their dynamics are mostly confined within nucleons, but residual influences extend slightly beyond nucleon boundaries to give rise to the nuclear force.

The nuclear forces arising between nucleons are analogous to the forces in chemistry between neutral atoms or molecules called London dispersion forces. Such forces between atoms are much weaker than the attractive electrical forces that hold the atoms themselves together (i.e., that bind electrons to the nucleus), and their range between atoms is shorter, because they arise from small separation of charges inside the neutral atom.[further explanation needed] Similarly, even though nucleons are made of quarks in combinations which cancel most gluon forces (they are "colour neutral"), some combinations of quarks and gluons nevertheless leak away from nucleons, in the form of short-range nuclear force fields that extend from one nucleon to another nearby nucleon. These nuclear forces are very weak compared to direct gluon forces ("colour forces" or strong forces) inside nucleons, and the nuclear forces extend only over a few nuclear diameters, falling exponentially with distance. Nevertheless, they are strong enough to bind neutrons and protons over short distances, and overcome the electrical repulsion between protons in the nucleus.

Sometimes, the nuclear force is called the residual strong force, in contrast to the strong interactions which arise from QCD. This phrasing arose during the 1970s when QCD was being established. Before that time, the strong nuclear force referred to the inter-nucleon potential. After the verification of the quark model, strong interaction has come to mean QCD.

Nucleon–nucleon potentials

[edit]Two-nucleon systems such as the deuteron, the nucleus of a deuterium atom, as well as proton–proton or neutron–proton scattering are ideal for studying the NN force. Such systems can be described by attributing a potential (such as the Yukawa potential) to the nucleons and using the potentials in a Schrödinger equation. The form of the potential is derived phenomenologically (by measurement), although for the long-range interaction, meson-exchange theories help to construct the potential. The parameters of the potential are determined by fitting to experimental data such as the deuteron binding energy or NN elastic scattering cross sections (or, equivalently in this context, so-called NN phase shifts).

The most widely used NN potentials are the Paris potential, the Argonne AV18 potential,[16] the CD-Bonn potential, and the Nijmegen potentials.

A more recent approach is to develop effective field theories for a consistent description of nucleon–nucleon and three-nucleon forces. Quantum hadrodynamics is an effective field theory of the nuclear force, comparable to QCD for colour interactions and QED for electromagnetic interactions. Additionally, chiral symmetry breaking can be analyzed in terms of an effective field theory (called chiral perturbation theory) which allows perturbative calculations of the interactions between nucleons with pions as exchange particles.

From nucleons to nuclei

[edit]The ultimate goal of nuclear physics would be to describe all nuclear interactions from the basic interactions between nucleons. This is called the microscopic or ab initio approach of nuclear physics. There are two major obstacles to overcome:

- Calculations in many-body systems are difficult (because of multi-particle interactions) and require advanced computation techniques.

- There is evidence that three-nucleon forces (and possibly higher multi-particle interactions) play a significant role. This means that three-nucleon potentials must be included into the model.

This is an active area of research with ongoing advances in computational techniques leading to better first-principles calculations of the nuclear shell structure. Two- and three-nucleon potentials have been implemented for nuclides up to A = 12.

Nuclear potentials

[edit]A successful way of describing nuclear interactions is to construct one potential for the whole nucleus instead of considering all its nucleon components. This is called the macroscopic approach. For example, scattering of neutrons from nuclei can be described by considering a plane wave in the potential of the nucleus, which comprises a real part and an imaginary part. This model is often called the optical model since it resembles the case of light scattered by an opaque glass sphere.

Nuclear potentials can be local or global: local potentials are limited to a narrow energy range and/or a narrow nuclear mass range, while global potentials, which have more parameters and are usually less accurate, are functions of the energy and the nuclear mass and can therefore be used in a wider range of applications.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Reid, R. V. (1968). "Local phenomenological nucleon–nucleon potentials". Annals of Physics. 50 (3): 411–448. Bibcode:1968AnPhy..50..411R. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(68)90126-7.

- ^ Kenneth S. Krane (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-80553-X.

- ^ Binding Energy, Mass Defect Archived 2017-06-18 at the Wayback Machine, Furry Elephant physics educational site, retrieved 2012-07-01.

- ^ Chapter 4. NUCLEAR PROCESSES, THE STRONG FORCE Archived 2013-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, M. Ragheb, 1/30/2013, University of Illinois.

- ^ Povh, B.; Rith, K.; Scholz, C.; Zetsche, F. (2002). Particles and Nuclei: An Introduction to the Physical Concepts. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-540-43823-6.

- ^ Stern, Dr. Swapnil Nikam (February 11, 2009). "Nuclear Binding Energy". From Stargazers to Starships. NASA website. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ Griffiths, David, Introduction to Elementary Particles

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. I". Z. Phys. (in German). 77 (1–2): 1–11. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...77....1H. doi:10.1007/BF01342433. S2CID 186218053.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1932). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. II". Z. Phys. (in German). 78 (3–4): 156–164. Bibcode:1932ZPhy...78..156H. doi:10.1007/BF01337585. S2CID 186221789.

- ^ Heisenberg, W. (1933). "Über den Bau der Atomkerne. III". Z. Phys. (in German). 80 (9–10): 587–596. Bibcode:1933ZPhy...80..587H. doi:10.1007/BF01335696. S2CID 126422047.

- ^ Iwanenko, D. D., The neutron hypothesis, Nature 129 (1932) 798.

- ^ Miller A. I. Early Quantum Electrodynamics: A Sourcebook, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995, ISBN 0521568919, pp. 84–88.

- ^ Brown, L. M.; Rechenberg, H. (1996). The Origin of the Concept of Nuclear Forces. Bristol and Philadelphia: Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0-7503-0373-5. Archived from the original on 2023-12-30. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ a b John S. Rigden (1987). Rabi, Scientist and Citizen. New York: Basic Books, Inc. pp. 99–114. ISBN 978-0-674-00435-1. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Kellogg, J. M.; Rabi, I. I.; Ramsey, N. F.; Zacharias, J. R. (1939). "An electrical quadrupole moment of the deuteron". Physical Review. 55 (3): 318–319. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..318K. doi:10.1103/physrev.55.318. Archived from the original on May 12, 2017. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Wiringa, R. B.; Stoks, V. G. J.; Schiavilla, R. (1995). "Accurate nucleon–nucleon potential with charge-independence breaking". Physical Review C. 51 (1): 38–51. arXiv:nucl-th/9408016. Bibcode:1995PhRvC..51...38W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.51.38. PMID 9970037. S2CID 118937727.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gerald Edward Brown and A. D. Jackson (1976). The Nucleon–Nucleon Interaction. Amsterdam North-Holland Publishing. ISBN 0-7204-0335-9.

- R. Machleidt and I. Slaus, "The nucleon–nucleon interaction" Archived 2021-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, J. Phys. G 27 (May 2001) R69. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/27/5/201. (Topical review.)

- E. A. Nersesov (1990). Fundamentals of atomic and nuclear physics. Moscow: Mir Publishers. ISBN 5-06-001249-2.

- Navrátil, Petr; Ormand, W. Erich (2003). "Ab initio shell model with a genuine three-nucleon force for the p-shell nuclei". Physical Review C. 68 (3) 034305. arXiv:nucl-th/0305090. Bibcode:2003PhRvC..68c4305N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.68.034305. S2CID 119091461.

Further reading

[edit]- Ruprecht Machleidt, "Nuclear Forces", Scholarpedia, 9(1):30710. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.30710.

Nuclear force

View on GrokipediaFundamental Properties

Strength and range

The nuclear force, also known as the strong nuclear force between nucleons, is the most powerful of the four fundamental interactions at short distances, with a relative strength approximately 100 times that of the electromagnetic force between two protons in close proximity.[4] In comparison to the weak nuclear force, it is about 10^{13} times stronger, while it exceeds the gravitational force by a factor of roughly 10^{38}.[4] These ratios highlight the nuclear force's dominant role in overcoming electromagnetic repulsion within atomic nuclei, enabling stable binding of protons and neutrons.[5] The nuclear force operates over an extremely limited spatial range, effective only up to about 2-3 femtometers (fm), which corresponds roughly to the diameter of atomic nuclei.[1] Beyond this distance, the force diminishes exponentially to negligible levels, confining its influence to the scale of nuclear dimensions and preventing it from affecting larger structures like atoms or molecules.[6] A key characteristic of the nuclear force is its saturation property, whereby the attractive interaction does not accumulate indefinitely with increasing numbers of nucleons but instead reaches a balance that results in a nearly constant nuclear density of approximately 0.16-0.17 nucleons per fm³ across most heavy nuclei.[7] This saturation arises from the short-range nature of the force combined with short-range repulsive components at very close distances, limiting each nucleon's binding to a fixed number of neighbors and preventing indefinite clustering.[1] Consequently, the binding energy per nucleon stabilizes at around 8 MeV for medium to heavy nuclei, reflecting this finite interaction capacity.[8] Empirical evidence for the finite range of the nuclear force comes primarily from nucleon-nucleon scattering experiments, which reveal that the interaction vanishes at separations greater than a few fm, as indicated by the absence of significant scattering phase shifts at larger impact parameters.[1] High-energy scattering data, particularly above 200 MeV, further demonstrate a transition to repulsive behavior at distances below 0.5 fm, confirming the force's sharp cutoff and supporting models of its limited extent.[1]Charge independence and isospin

The nuclear force exhibits charge independence, meaning that the strong interaction between two protons (pp), two neutrons (nn), and a proton-neutron pair (np) is essentially the same in magnitude and form, disregarding small corrections from electromagnetic interactions.[9][10] This property arises because the strong force, mediated by the exchange of gluons between quarks, does not distinguish between the electric charges of protons and neutrons at leading order.[11] Charge independence is formalized through the concept of isospin, an approximate SU(2) symmetry in the strong interaction that treats protons and neutrons as two states of a single particle, the nucleon, with total isospin .[10] In this framework, the proton corresponds to the state with third-component isospin , while the neutron has , analogous to the up and down states of a spin- particle.[10] The SU(2) group structure allows nucleons to form isospin multiplets, enabling the classification of nuclear states and interactions under rotations in isospin space, where the strong force conserves total isospin and .[10] This symmetry originates from the near-degeneracy of the up and down quark masses in quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the underlying theory of strong interactions.[11] Experimental verification of charge independence comes from nucleon-nucleon scattering experiments, where the differential and total cross-sections for pp, nn, and np scattering show striking similarities at low energies after correcting for Coulomb effects in charged pairs.[12] For instance, in the channel (as of 2023 measurements), the nuclear s-wave scattering lengths are fm for nn, fm for pp (Coulomb-free), and fm for np, demonstrating close equivalence between like-nucleon pairs and the distinction for np due to isospin channels.[12] Such measurements, obtained via techniques like the Trojan Horse method in quasi-free reactions, confirm that the nuclear force operates symmetrically across isospin channels, with deviations primarily attributable to non-strong effects.[12] Despite its successes, charge independence is violated at the level of a few percent due to electromagnetic interactions and the up-down quark mass difference ( MeV).[13] Electromagnetic contributions include Coulomb repulsion in pp scattering and pion mass splittings ( MeV), which introduce charge-dependent potentials; these account for much of the observed charge independence breaking (CIB) in scattering lengths, quantified by fm (2023 values), mainly from the I=0 (np singlet) vs. I=1 (pp, nn) difference.[12] Charge symmetry breaking (CSB), the smaller pp-nn difference fm, arises additionally from quark mass effects.[12] The quark mass difference generates strong-interaction violations through higher-order QCD effects, contributing to differences like the neutron-proton mass splitting ( MeV, with ~0.8 MeV from electromagnetism and the rest from quarks).[11] These violations manifest as ~1-2% deviations in binding energies of mirror nuclei and scattering observables, underscoring the approximate nature of the SU(2) symmetry.[11]Historical Development

Early discoveries

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford conducted alpha particle scattering experiments on thin gold foil, observing that a small fraction of particles were deflected at large angles, which could only be explained by the presence of a tiny, dense, positively charged nucleus at the atom's center. This discovery implied that the nucleus must be held together by a powerful attractive force to counteract the electromagnetic repulsion between its positively charged protons.[14] The 1930s brought key experimental observations of interactions between neutrons and protons, highlighting the nuclear force's role. In 1930, Walther Bothe and Herbert Becker bombarded beryllium with alpha particles, producing a highly penetrating neutral radiation that interacted strongly with matter. James Chadwick, in 1932, identified this radiation as neutrons by measuring their scattering off protons in paraffin wax, where the recoil protons' energies indicated a neutral particle of mass approximately equal to the proton, demonstrating a strong neutron-proton interaction. These experiments also revealed the binding of the deuteron, the simplest nucleus composed of one proton and one neutron, with a binding energy of about 2.2 MeV, providing direct evidence of an attractive force between unlike nucleons.[15][16] In 1932, Werner Heisenberg proposed a theoretical framework for nuclear binding, suggesting the neutron as a tightly bound proton-electron composite and attributing the nuclear force to the quantum mechanical exchange of electrons between protons, analogous to exchange forces in molecular bonds; this model, though later revised after confirming the neutron's elementary nature, introduced the concept of exchange mechanisms for short-range nuclear interactions. By 1936, Hans Bethe and Robert F. Bacher's comprehensive review synthesized these developments, emphasizing empirical evidence for nuclear forces, including neutron-proton scattering data. Notably, measurements of neutron-proton radiative capture cross-sections, which showed anomalously large values for slow neutrons (on the order of barns), indicated a short-range attractive potential that enhanced low-energy interactions, underscoring the force's non-electromagnetic character and limited range of about 1-2 femtometers.[17][18]Key theoretical advances

The discovery of the pion in 1947 by Cecil F. Powell and collaborators, through cosmic ray emulsion experiments, provided experimental confirmation of Hideki Yukawa's 1935 hypothesis that a meson mediates the nuclear force, with the pion's mass of approximately 140 MeV aligning closely with Yukawa's prediction for the mediator particle. In the 1950s, pion-nucleon scattering experiments, such as those conducted at the University of Chicago's synchrocyclotron in 1951, established the pseudoscalar nature of the pion coupling to nucleons, supporting Yukawa's meson theory and enabling more accurate models of the strong interaction.[19] Additionally, the 1956 proposal by Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang of parity nonconservation in weak interactions, experimentally verified in 1957 by Chien-Shiung Wu and others, prompted a reevaluation of symmetry principles in strong force models, influencing the incorporation of chiral symmetries in pion-nucleon interactions.[20] The 1960s marked a paradigm shift with the independent proposals of the quark model by Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig in 1964, positing that protons and neutrons consist of three quarks, which provided a deeper substructure for understanding the nuclear force as a residual effect of quark interactions. To resolve issues with quark statistics and identical particle behavior, Oscar W. Greenberg introduced color charge as a three-valued quantum number in 1964, laying the groundwork for the color degree of freedom essential to strong interactions. In 1973, Harald Fritzsch, Murray Gell-Mann, and Heinrich Leutwyler formulated quantum chromodynamics (QCD) as the gauge theory of the strong interaction, incorporating color charge and gluons as mediators between quarks.[21] That same year, David Gross and Frank Wilczek, along with independently David Politzer, demonstrated asymptotic freedom in non-Abelian gauge theories like QCD, explaining how the strong force weakens at short distances (high energies) and strengthens at longer distances, thus unifying perturbative and non-perturbative regimes for nuclear force descriptions. During the 1990s, advances in lattice QCD simulations, building on Kenneth Wilson's foundational work, enabled non-perturbative calculations of nuclear forces directly from QCD, with early quark-included computations toward the decade's end providing insights into nucleon interactions beyond phenomenological models.[22] More recently, the HAL QCD collaboration has extended these simulations to finite nuclear densities, offering updated potentials relevant to dense matter.Theoretical Framework

Residual strong interaction

The nuclear force, which binds protons and neutrons within atomic nuclei, emerges as a residual effect of the strong interaction described by quantum chromodynamics (QCD). In QCD, the fundamental strong force is mediated by gluons, which carry color charge and couple quarks— the building blocks of hadrons— in a non-Abelian gauge theory, leading to the phenomenon of color confinement where quarks are perpetually bound within colorless hadrons such as nucleons.[23] This confinement ensures that isolated quarks cannot exist, and the resulting hadrons interact via residual color forces that manifest at larger scales.[24] The residual strong interaction arises from the exchange of quarks and gluons between neighboring nucleons, analogous to van der Waals forces in atomic physics, where fluctuating dipoles induce attractions between neutral atoms. Specifically, when two color-neutral nucleons approach each other, their constituent quarks can exchange color-charged gluons or intermediate states like mesons, but the overall exchange must preserve color neutrality for the composite systems, resulting in an effective attraction at nuclear distances of about 1-2 femtometers.[23] This process effectively transfers momentum and energy between nucleons without violating QCD's color confinement principle.[24] A key distinction in QCD lies in the scale separation between the microscopic quark-gluon dynamics at short distances (high energies, ~1 GeV) and the effective low-energy regime governing nuclear structure (~100 MeV), where perturbative QCD breaks down, necessitating effective field theories to bridge the gap.[23] Recent lattice QCD simulations have provided insights into how spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking— a non-perturbative effect where the approximate chiral symmetry of massless quarks is broken by the QCD vacuum, generating light pion masses— influences the residual nuclear force, particularly in constraining in-medium interactions and three-body forces that contribute to nuclear saturation.[25] These computations demonstrate that chiral symmetry restoration at high densities alters the nuclear potential, linking fundamental QCD mechanisms directly to observable nuclear properties.[25]Meson exchange theory

The meson exchange theory posits that the nuclear force arises from the exchange of mesons between nucleons, providing an effective description that bridges the underlying quantum chromodynamics (QCD) with phenomenological models of nucleon interactions. In 1935, Hideki Yukawa proposed that this force is mediated by the exchange of massive particles, termed mesons, which carry the strong interaction over short distances, characterized by a coupling constant that quantifies the strength of the nucleon-meson vertex. This idea successfully explained the short range of the nuclear force, limited by the mesons' mass, and anticipated the discovery of pions as the lightest mesons responsible for the longest-range component. The one-pion exchange (OPE) represents the dominant long-range contribution to the nuclear force, arising from the virtual exchange of a single pion between nucleons, and it exhibits strong spin and isospin dependence. The OPE potential is pseudoscalar in nature, leading to both central and tensor components that influence nucleon scattering and bound states. The standard form of the OPE potential in coordinate space is where , , , is the dimensionless pion-nucleon coupling constant (with ), and is the tensor operator. This tensor term is particularly crucial, as it drives the mixing between spin-singlet and spin-triplet states in deuteron-like configurations, and at short distances (), it exhibits a singular behavior.[11] For shorter ranges, the theory incorporates multi-pion exchanges, which account for intermediate-distance attractions, as well as contributions from heavier vector mesons such as the rho () and omega (), which introduce repulsive cores at very short distances below 1 fm. The rho meson exchange provides an isovector tensor force, while the omega contributes a central isoscalar repulsion, both essential for reproducing the empirical hard core in nucleon-nucleon potentials. These heavier meson exchanges, with masses around 770 MeV for rho and 783 MeV for omega, ensure the potential's rapid falloff at small separations, aligning with scattering data.[11] Extensions of meson exchange theory within chiral perturbation theory (ChPT) provide a systematic, low-energy effective field theory framework, deriving the interactions from a chiral-invariant Lagrangian that respects the approximate SU(2)_L × SU(2)_R symmetry of QCD. In ChPT, the pion-nucleon coupling is expanded in powers of momentum over the chiral symmetry breaking scale (~1 GeV), with the leading-order term corresponding to the OPE and higher orders including multi-pion loops and contact terms.[26] Recent advances in chiral effective field theory, including relativistic formulations, have enhanced predictions for nuclear interactions and structure calculations as of 2025.[27][28] This approach renormalizes the theory order by order, improving predictions for low-energy nucleon-nucleon scattering phases and enabling connections to lattice QCD simulations.[11]Interaction Models

Yukawa potential

The Yukawa potential represents the simplest phenomenological model for the nuclear force, proposed by Hideki Yukawa in 1935 as arising from the exchange of a massive scalar particle, termed a "meson," between nucleons. This model extended the concept of field-mediated interactions, analogous to electromagnetism, to account for the short-range nature of the strong nuclear force.[29] The potential takes the form where is the distance between nucleons, is the dimensionless coupling constant between the nucleon and the meson field, and is the mass of the exchanged meson. This expression describes an attractive, centrally symmetric force that decays exponentially, with the range determined by the meson's mass.[30] This form derives from the static limit of the Klein-Gordon equation for a massive scalar field exchanged between two nucleons. The Klein-Gordon equation in the static case, , yields the Green's function solution , which, upon incorporating the coupling, produces the Yukawa potential. The finite mass introduces the exponential screening, contrasting with the infinite-range Coulomb potential from massless photon exchange.[30] Yukawa applied this potential to the deuteron, the simplest bound nucleon system with a binding energy of 2.224 MeV and size approximately 2 fm, to estimate the meson mass. Fitting the potential parameters to reproduce the deuteron's binding yielded MeV, a prediction made over a decade before the meson's experimental identification.[29][30] Despite its foundational role, the simple scalar Yukawa potential has notable limitations: it assumes a spin-independent, isoscalar interaction, failing to capture the observed tensor and spin-orbit components of the nuclear force, as well as charge independence via isospin. These shortcomings were later addressed by incorporating vector meson exchanges alongside the scalar term. Yukawa's 1935 proposal gained empirical validation in 1947 when Cecil Powell and collaborators discovered the charged pion () in cosmic-ray interactions using nuclear emulsions, confirming a mass of approximately 140 MeV and establishing it as the predicted mediator. This breakthrough earned Yukawa the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physics and solidified meson exchange as a cornerstone of nuclear theory.[29]Modern nucleon-nucleon potentials

Modern nucleon-nucleon (NN) potentials are phenomenological or semi-phenomenological models constructed to accurately reproduce empirical NN scattering data, such as phase shifts from proton-proton (pp) and neutron-proton (np) interactions, deuteron properties, and low-energy parameters. These potentials incorporate the effects of spin and isospin dependencies, as well as a strong short-range repulsion to account for the finite size of nucleons and Pauli exclusion, while fitting data up to laboratory energies of several hundred MeV. Unlike simpler theoretical prototypes like the Yukawa potential, modern potentials use multi-parameter forms with local or nonlocal radial dependencies, enabling high-precision descriptions of the NN interaction across partial waves.[31] A seminal example from the 1960s is the Reid soft-core potential, developed by fitting to early NN scattering phase shifts and low-energy data. This local potential includes central, tensor, and spin-orbit components, with a Gaussian form for the short-range repulsion to soften the core while avoiding unphysical singularities. The radial functions are parameterized as sums of Yukawa terms for the attractive meson-exchange-like parts, modulated by operator structures that depend on the total spin , orbital angular momentum , and isospin . It achieved good agreement with np and pp data up to 350 MeV, influencing subsequent nuclear structure calculations.[31] In the 1980s, the Paris potential advanced this approach by blending meson-exchange theory with phenomenological elements, providing a nonlocal, momentum-dependent description fitted to NN phase shifts up to 330 MeV. Inspired by dispersion relations and - and -meson exchanges for longer ranges, it features a phenomenological core to model short-distance repulsion, with parameters adjusted to match scattering data and deuteron observables like the binding energy and quadrupole moment. This potential improved predictions for higher partial waves and was widely used in few-body nuclear systems. High-precision potentials emerged in the 1990s, such as the Argonne v18 and CD-Bonn models, which fit vast datasets of np and pp scattering phases up to 1 GeV, achieving per datum close to unity across thousands of data points. The Argonne v18 is a local potential with 18 operator components, including charge-dependent terms to capture small isospin-breaking effects from electromagnetic interactions and differences in pp versus np forces; it uses Woods-Saxon derivatives for short-range repulsion and Yukawa forms for meson exchanges. Similarly, the CD-Bonn potential employs a nonlocal, meson-exchange framework with one-boson-exchange (OBE) terms for , , , , and others, plus phenomenological short-range components, explicitly incorporating charge dependence to fit pp and np data separately. Both potentials reproduce the deuteron binding energy to within 0.1% and have and 1.01, respectively, for comprehensive databases.[32] The general operator structure of these modern potentials expands the NN interaction in a basis of spin-isospin operators, typically written as where the include the central , tensor , spin-orbit , and quadratic spin operators like , multiplied by isospin factors such as , , and charge-breaking terms like . The radial functions are fitted to data, often combining exponential or Yukawa forms for attraction with repulsive cores. This structure captures the complexity of the strong force while respecting approximate isospin symmetry.[32][31] More recent developments in the 2010s incorporate chiral effective field theory (EFT) to derive NN potentials systematically from QCD symmetries, with the Entem-Machleidt models providing high-fidelity fits up to next-to-next-to-next-to-leading order (N4LO). These potentials use pion-exchange diagrams for long-range attraction and contact terms for short-range physics, achieving accuracy comparable to phenomenological models ( up to 450 MeV) while including explicit -resonance intermediate states to improve the description of tensor force and spin-orbit coupling. For instance, the N3LO version fits over 4300 pp and np data points with a deuteron binding energy of 2.2246 MeV, demonstrating convergence in the chiral expansion.[33]Role in Nuclear Structure

Binding energy contributions

The nuclear binding energy for a nucleus with mass number and atomic number is defined as the energy required to disassemble it into its constituent protons and neutrons, given by the formulawhere and are the masses of the proton and neutron, respectively, is the mass of the nucleus, and is the speed of light. This energy arises predominantly from the attractive nuclear force, which overcomes the repulsive Coulomb interactions between protons and provides the stability of the nucleus.[34] The semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF) approximates the binding energy as a sum of several terms that capture different physical effects: a volume term , a surface term , a Coulomb term , an asymmetry term , and a pairing term that depends on whether is even or odd. The nuclear force primarily governs the volume term, reflecting its short-range attractive nature that binds nucleons uniformly throughout the nuclear volume, while the surface term accounts for the reduced binding at the nuclear periphery due to fewer nucleon neighbors. The other terms arise from electromagnetic repulsion, neutron-proton imbalance, and quantum statistical effects, but the nuclear force's contribution dominates the overall scale of binding.[35] In the simplest two-body system, the deuteron (comprising a proton and neutron), the nuclear force yields a binding energy of 2.224 MeV through the attractive interaction in the spin-triplet state, demonstrating the force's role in stabilizing light nuclei against dissociation. For heavier nuclei, binding energy saturation occurs, with an average of approximately 8 MeV per nucleon, resulting from the balance between the nuclear force's medium-range attraction and its short-range repulsion, which prevents collapse and limits each nucleon's interactions to nearest neighbors. This saturation explains the near-constant binding per nucleon across medium-mass nuclei. In light nuclei, such as the triton (³H), two-body nuclear forces alone underbind the system by about 1-2 MeV compared to the observed 8.48 MeV binding energy, a discrepancy known as the triton puzzle. Effective field theory (EFT) calculations in the 2020s, incorporating three-body forces derived from chiral EFT, resolve this by adding contact terms that enhance binding, accurately reproducing the triton energy and related scattering data when fitted to empirical inputs. These three-body contributions, arising from multi-pion exchanges and short-range effects, become essential for precise descriptions beyond the two-body approximation.[36][37]