Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

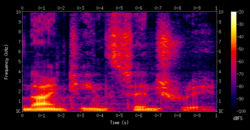

Spectrogram

View on Wikipedia

A spectrogram is a visual representation of the spectrum of frequencies of a signal as it varies with time. When applied to an audio signal, spectrograms are sometimes called sonographs, voiceprints, or voicegrams. When the data are represented in a 3D plot they may be called waterfall displays.

Spectrograms are used extensively in the fields of music, linguistics, sonar, radar, speech processing,[1] seismology, ornithology, and others. Spectrograms of audio can be used to identify spoken words phonetically, and to analyse the various calls of animals.

A spectrogram can be generated by an optical spectrometer, a bank of band-pass filters, by Fourier transform or by a wavelet transform (in which case it is also known as a scaleogram or scalogram).[2]

A spectrogram is usually depicted as a heat map, i.e., as an image with the intensity shown by varying the colour or brightness.

Format

[edit]A common format is a graph with two geometric dimensions: one axis represents time, and the other axis represents frequency; a third dimension indicating the amplitude of a particular frequency at a particular time is represented by the intensity or color of each point in the image.

There are many variations of format: sometimes the vertical and horizontal axes are switched, so time runs up and down; sometimes as a waterfall plot where the amplitude is represented by height of a 3D surface instead of color or intensity. The frequency and amplitude axes can be either linear or logarithmic, depending on what the graph is being used for. Audio would usually be represented with a logarithmic amplitude axis (probably in decibels, or dB), and frequency would be linear to emphasize harmonic relationships, or logarithmic to emphasize musical, tonal relationships.

-

Spectrogram of this recording of a violin playing. Note the harmonics occurring at whole-number multiples of the fundamental frequency.

-

3D surface spectrogram of a part from a music piece.

-

Spectrogram of a male voice saying 'ta ta ta'.

-

Spectrogram of dolphin vocalizations; chirps, clicks and harmonizing are visible as inverted Vs, vertical lines and horizontal striations respectively.

-

Spectrogram of an FM signal. In this case the signal frequency is modulated with a sinusoidal frequency vs. time profile.

-

Spectrum above and waterfall (Spectrogram) below of an 8MHz wide PAL-I Television signal.

-

Spectrogram of great tit song.

-

Constant-Q spectrogram of a gravitational wave (GW170817).

-

Spectrogram and waterfalls of 3 whistled notes.

-

Spectrogram of the soundscape ecology of Mount Rainier National Park, with the sounds of different creatures and aircraft highlighted

-

Spectrogram (generated with the freeware Sonogram visible Speech).

-

Variable-Q transform spectrogram of a piano chord (generated using FFmpeg's showcqt filter).

Generation

[edit]Spectrograms of light may be created directly using an optical spectrometer over time.

Spectrograms may be created from a time-domain signal in one of two ways: approximated as a filterbank that results from a series of band-pass filters (this was the only way before the advent of modern digital signal processing), or calculated from the time signal using the Fourier transform. These two methods actually form two different time–frequency representations, but are equivalent under some conditions.

The bandpass filters method usually uses analog processing to divide the input signal into frequency bands; the magnitude of each filter's output controls a transducer that records the spectrogram as an image on paper.[3]

Creating a spectrogram using the FFT is a digital process. Digitally sampled data, in the time domain, is broken up into chunks, which usually overlap, and Fourier transformed to calculate the magnitude of the frequency spectrum for each chunk. Each chunk then corresponds to a vertical line in the image; a measurement of magnitude versus frequency for a specific moment in time (the midpoint of the chunk). These spectrums or time plots are then "laid side by side" to form the image or a three-dimensional surface,[4] or slightly overlapped in various ways, i.e. windowing. This process essentially corresponds to computing the squared magnitude of the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) of the signal — that is, for a window width , .[5]

Limitations and resynthesis

[edit]From the formula above, it appears that a spectrogram contains no information about the exact, or even approximate, phase of the signal that it represents. For this reason, it is not possible to reverse the process and generate a copy of the original signal from a spectrogram, though in situations where the exact initial phase is unimportant it may be possible to generate a useful approximation of the original signal. The Analysis & Resynthesis Sound Spectrograph[6] is an example of a computer program that attempts to do this. The pattern playback was an early speech synthesizer, designed at Haskins Laboratories in the late 1940s, that converted pictures of the acoustic patterns of speech (spectrograms) back into sound.

In fact, there is some phase information in the spectrogram, but it appears in another form, as time delay (or group delay) which is the dual of the instantaneous frequency.[7]

The size and shape of the analysis window can be varied. A smaller (shorter) window will produce more accurate results in timing, at the expense of precision of frequency representation. A larger (longer) window will provide a more precise frequency representation, at the expense of precision in timing representation. This is an instance of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, that the product of the precision in two conjugate variables is greater than or equal to a constant (B*T>=1 in the usual notation).[8]

Applications

[edit]- Early analog spectrograms were applied to a wide range of areas including the study of bird calls (such as that of the great tit), with current research continuing using modern digital equipment[9] and applied to all animal sounds. Contemporary use of the digital spectrogram is especially useful for studying frequency modulation (FM) in animal calls. Specifically, the distinguishing characteristics of FM chirps, broadband clicks, and social harmonizing are most easily visualized with the spectrogram.

- Spectrograms are useful in assisting in overcoming speech deficits and in speech training for the portion of the population that is profoundly deaf.[10]

- The studies of phonetics and speech synthesis are often facilitated through the use of spectrograms.[11][12]

- In deep learning-keyed speech synthesis, spectrogram (or spectrogram in mel scale) is first predicted by a seq2seq model, then the spectrogram is fed to a neural vocoder to derive the synthesized raw waveform.

- By reversing the process of producing a spectrogram, it is possible to create a signal whose spectrogram is an arbitrary image. This technique can be used to hide a picture in a piece of audio and has been employed by several electronic music artists.[13] See also Steganography.

- Some modern music is created using spectrograms as an intermediate medium; changing the intensity of different frequencies over time, or even creating new ones, by drawing them and then inverse transforming. See Audio timescale-pitch modification and Phase vocoder.

- Spectrograms can be used to analyze the results of passing a test signal through a signal processor such as a filter in order to check its performance.[14]

- High definition spectrograms are used in the development of RF and microwave systems.[15]

- Spectrograms are now used to display scattering parameters measured with vector network analyzers.[16]

- The US Geological Survey and the IRIS Consortium provide near real-time spectrogram displays for monitoring seismic stations.[17][18]

- Spectrograms can be used with recurrent neural networks for speech recognition.[19][20]

- Individuals' spectrograms are collected by the Chinese government as part of its mass surveillance programs.[21]

- For a vibration signal, a spectrogram's color scale identifies the frequencies of a waveform's amplitude peaks over time. Unlike a time or frequency graph, a spectrogram correlates peak values to time and frequency. Vibration test engineers use spectrograms to analyze the frequency content of a continuous waveform, locating strong signals and determining how the vibration behavior changes over time.[22]

- Spectrograms can be used to analyze speech in two different applications: automatic detection of speech deficits in cochlear implant users and phoneme class recognition to extract phone-attribute features.[23]

- In order to obtain a speaker's pronunciation characteristics, some researchers proposed a method based on an idea from bionics, which uses spectrogram statistics to achieve a characteristic spectrogram to give a stable representation of the speaker's pronunciation from a linear superposition of short-time spectrograms.[24]

- Researchers explore a novel approach to ECG signal analysis by leveraging spectrogram techniques, possibly for enhanced visualization and understanding. The integration of MFCC for feature extraction suggests a cross-disciplinary application, borrowing methods from audio processing to extract relevant information from biomedical signals.[25]

- Accurate interpretation of temperature indicating paint (TIP) is of great importance in aviation and other industrial applications. 2D spectrogram of TIP can be used in temperature interpretation.[26]

- The spectrogram can be used to process the signal for the rate of change of the human thorax. By visualizing respiratory signals using a spectrogram, the researchers have proposed an approach to the classification of respiration states based on a neural network model.[27]

See also

[edit]- Acoustic signature

- Chromagram

- Fourier analysis for computing periodicity in evenly spaced data

- Generalized spectrogram

- Least-squares spectral analysis for computing periodicity in unevenly spaced data

- List of unexplained sounds

- Reassignment method

- Spectral music

- Spectrometer

- Strobe tuner

- Waveform

References

[edit]- ^ JL Flanagan, Speech Analysis, Synthesis and Perception, Springer- Verlag, New York, 1972

- ^ Sejdic, E.; Djurovic, I.; Stankovic, L. (August 2008). "Quantitative Performance Analysis of Scalogram as Instantaneous Frequency Estimator". IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 56 (8): 3837–3845. Bibcode:2008ITSP...56.3837S. doi:10.1109/TSP.2008.924856. ISSN 1053-587X. S2CID 16396084.

- ^ "Spectrograph". www.sfu.ca. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Spectrograms". ccrma.stanford.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "STFT Spectrograms VI – NI LabVIEW 8.6 Help". zone.ni.com. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "The Analysis & Resynthesis Sound Spectrograph". arss.sourceforge.net. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Boashash, B. (1992). "Estimating and interpreting the instantaneous frequency of a signal. I. Fundamentals". Proceedings of the IEEE. 80 (4). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): 520–538. doi:10.1109/5.135376. ISSN 0018-9219.

- ^ "Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle". Archived from the original on 2019-01-25. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- ^ "BIRD SONGS AND CALLS WITH SPECTROGRAMS ( SONOGRAMS ) OF SOUTHERN TUSCANY ( Toscana – Italy )". www.birdsongs.it. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ Saunders, Frank A.; Hill, William A.; Franklin, Barbara (1 December 1981). "A wearable tactile sensory aid for profoundly deaf children". Journal of Medical Systems. 5 (4): 265–270. doi:10.1007/BF02222144. PMID 7320662. S2CID 26620843.

- ^ "Spectrogram Reading". ogi.edu. Archived from the original on 27 April 1999. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Praat: doing Phonetics by Computer". www.fon.hum.uva.nl. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "The Aphex Face – bastwood". www.bastwood.com. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "SRC Comparisons". src.infinitewave.ca. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "constantwave.com – constantwave Resources and Information". www.constantwave.com. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "Spectrograms for vector network analyzers". Archived from the original on 2012-08-10.

- ^ "Real-time Spectrogram Displays". earthquake.usgs.gov. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "IRIS: MUSTANG: Noise-Spectrogram: Docs: v. 1: Help".

- ^ Geitgey, Adam (2016-12-24). "Machine Learning is Fun Part 6: How to do Speech Recognition with Deep Learning". Medium. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ^ See also Praat.

- ^ "China's enormous surveillance state is still growing". The Economist. November 23, 2023. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

- ^ "What is a Spectrogram?". Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ T., Arias-Vergara; P., Klumpp; J. C., Vasquez-Correa; E., Nöth; J. R., Orozco-Arroyave; M., Schuster (2021). "Multi-channel spectrograms for speech processing applications using deep learning methods". Pattern Analysis and Applications. 24 (2): 423–431. doi:10.1007/s10044-020-00921-5.

- ^ Jia, Yanjie; Chen, Xi; Yu, Jieqiong; Wang, Lianming; Xu, Yuanzhe; Liu, Shaojin; Wang, Yonghui (2021). "Speaker recognition based on characteristic spectrograms and an improved self-organizing feature map neural network". Complex & Intelligent Systems. 7 (4): 1749–1757. doi:10.1007/s40747-020-00172-1.

- ^ Yalamanchili, Arpitha; Madhumathi, G. L.; Balaji, N. (2022). "Spectrogram analysis of ECG signal and classification efficiency using MFCC feature extraction technique". Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing. 13 (2): 757–767. doi:10.1007/s12652-021-02926-2. S2CID 233657057.

- ^ Ge, Junfeng; Wang, Li; Gui, Kang; Ye, Lin (30 September 2023). "Temperature interpretation method for temperature indicating paint based on spectrogram". Measurement. 219. Bibcode:2023Meas..21913317G. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113317. S2CID 259871198.

- ^ Park, Cheolhyeong; Lee, Deokwoo (11 February 2022). "Classification of Respiratory States Using Spectrogram with Convolutional Neural Network". Applied Sciences. 12 (4): 1895. doi:10.3390/app12041895.

External links

[edit]- See an online spectrogram of speech or other sounds captured by your computer's microphone.

- Generating a tone sequence whose spectrogram matches an arbitrary text, online

- Further information on creating a signal whose spectrogram is an arbitrary image

- Article describing the development of a software spectrogram

- History of spectrograms & development of instrumentation

- How to identify the words in a spectrogram from a linguistic professor's Monthly Mystery Spectrogram publication.

- Sonogram Visible Speech GPL Licensed freeware for the Spectrogram generation of Signal Files.

Spectrogram

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Mathematical Foundation

A spectrogram provides a visual depiction of a signal's frequency spectrum evolving over time, with the horizontal axis representing time, the vertical axis frequency, and color or intensity encoding the amplitude of spectral components, often on a logarithmic scale such as decibels.[8] Mathematically, the spectrogram of a signal is the squared magnitude of its short-time Fourier transform (STFT), yielding a time-frequency energy density:[9][10] For a continuous-time signal , the STFT is defined as

where is a window function—typically real-valued and concentrated near zero—to restrict the Fourier analysis to a short interval around time , and denotes frequency in hertz.[10] Variations may include a complex conjugate on the window for analytic representations or angular frequency .[9] This formulation arises from applying the Fourier transform locally in time, balancing the global frequency resolution of the full Fourier transform with temporal localization. The window determines the trade-off: its duration inversely affects frequency resolution via the Fourier uncertainty principle, as narrower windows yield broader spectral spreads.[11] In discrete implementations, the integral becomes a summation over samples, with the exponential evaluated at discrete frequencies via the discrete Fourier transform.[11] The resulting spectrogram thus quantifies local power spectral density, enabling analysis of non-stationary signals where frequency content varies causally with time.[8]

Physical and Causal Interpretation

The spectrogram physically represents the local energy density of a signal in the time-frequency plane, where the horizontal axis denotes time, the vertical axis denotes frequency (in hertz, corresponding to oscillation cycles per second), and the color or brightness at each point quantifies the signal's power or squared amplitude at that frequency around that time. For acoustic signals, this maps to the distribution of kinetic and potential energy in air pressure oscillations, with brighter regions indicating higher-intensity vibrations at specific rates driven by the sound source.[7][12] The underlying short-time Fourier transform (STFT) decomposes the signal into overlapping windowed segments, each analyzed for sinusoidal components, yielding a physically interpretable approximation of how frequency-specific energy evolves, limited by the Heisenberg-Gabor uncertainty principle that trades time resolution for frequency resolution based on window length.[11][13] Causally, spectrogram features arise from the physical mechanisms generating the signal, such as periodic forcing in oscillatory systems producing sustained energy concentrations at resonant frequencies. In string instruments, for example, horizontal bands at integer multiples of the fundamental frequency reflect standing wave modes excited by the string's vibration, where the fundamental determines pitch via length, tension, and mass density per the wave equation , and overtones emerge from boundary conditions enforcing nodal points. Transient vertical streaks often signal impulsive causes like plucking or impact, releasing broadband energy that decays according to damping physics. This causal mapping enables inference of source dynamics: formant structures in speech, for instance, trace to vocal tract resonances shaped by anatomical configurations, while chirp-like sweeps in radar returns indicate accelerating targets via Doppler shifts proportional to relative velocity.[14][15] Limitations include windowing artifacts that smear causal events, as non-stationarities (e.g., sudden frequency shifts from mode coupling) violate the stationarity assumption implicit in Fourier analysis, necessitating validation against first-principles models of wave propagation and energy transfer.[16]Historical Development

Pre-20th Century Precursors

The phonautograph, invented by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville and patented on March 25, 1857, represented an early attempt to visually capture airborne sound waves by tracing their vibrations onto soot-covered paper or glass using a diaphragm-connected stylus. This device produced phonautograms—graphical representations of sound amplitude over time—but lacked frequency decomposition or playback capability, serving primarily for acoustic study rather than reproduction.[17] Scott's motivation stemmed from mimicking the human ear's structure to "write sound" for scientific analysis, predating Edison's phonograph by two decades and establishing a precedent for temporal visualization of acoustic signals.[18] In parallel, mid-19th-century advancements in frequency analysis emerged through Hermann von Helmholtz's vibration microscope, developed around the 1850s, which magnified diaphragm oscillations driven by sound to reveal vibrational patterns and harmonic interactions.[19] Helmholtz's 1863 treatise Die Lehre von den Tonempfindungen als physiologische Grundlage für die Theorie der Musik theoretically decomposed complex tones into sinusoidal components via resonance principles, influencing empirical tools for spectral breakdown without direct time-frequency plotting.[19] Rudolph Koenig, building on these foundations from the 1860s, engineered the manometric flame apparatus circa 1862, employing rotating gas flames sensitive to acoustic pressure for visualizing wave harmonics as modulated light patterns, enabling qualitative observation of frequency content in steady tones.[20] Koenig further refined this into a resonator-based sound analyzer by 1865, featuring tunable Helmholtz resonators to isolate specific frequencies from a composite sound, functioning as an analog precursor to spectrum analysis by selectively amplifying and detecting partials across a range of about 65 notes.[21] These devices, while static in frequency display and limited to continuous or quasi-steady signals, provided the causal insight that sound could be dissected into frequency elements for visual scrutiny, bridging amplitude-time traces and modern dynamic spectrographic methods.[22]World War II Origins and Early Devices

The sound spectrograph, the first practical device for generating spectrograms, was developed at Bell Laboratories by Ralph K. Potter and his team starting in early 1941, with the aim of producing visual representations of speech sounds interpretable by the human eye.[23] A rough laboratory prototype was completed by the end of 1941, just prior to the United States' entry into World War II.[23] This instrument functioned as a specialized wave analyzer, converting audio input into a permanent graphic record displaying the distribution of acoustic energy across frequency and time dimensions, thereby enabling detailed analysis of phonetic structure.[24] During World War II, the spectrograph's development accelerated under military auspices, with the first operational models deployed for cryptanalytic purposes to decode and identify speech patterns in intercepted communications.[25] Bell Labs engineers adapted the device to support Allied efforts in voice identification, allowing acoustic analysts to distinguish individual speakers from telephone and radio transmissions by revealing unique spectral signatures resistant to verbal disguise.[26] The U.S. military, including collaboration with agencies like the FBI, leveraged these early spectrographs to counter Axis radio traffic, marking the technology's initial real-world application in signals intelligence rather than its original civilian motivations of telephony improvement and speech education.[27] These wartime devices operated by recording sound onto a rotating magnetic drum, filtering it through a bank of bandpass filters spanning approximately 0 to 8000 Hz, and plotting intensity as darkness on electrosensitive paper, with time advancing horizontally and frequency vertically.[28] Typical analysis windows were short, on the order of 0.0025 to 0.064 seconds, to capture rapid phonetic transients, though resolution trade-offs between time and frequency were inherent due to the analog filtering constraints.[29] Post-war declassification in 1945–1946 revealed the spectrograph's efficacy, as documented in technical papers by Potter and colleagues, confirming its role in advancing empirical speech analysis amid the era's secrecy.[27][24]Post-War Advancements

In the immediate post-World War II period, the sound spectrograph transitioned from classified military use to commercial availability, enabling broader scientific application. In 1951, Kay Electric Company, under license from Bell Laboratories, introduced the first commercial model known as the Sona-Graph, which produced two-dimensional visualizations of sound spectra with time on the horizontal axis and frequency on the vertical axis, where darkness indicated energy intensity.[30][31] This device facilitated detailed analysis of speech formants and acoustic patterns, supplanting earlier impressionistic phonetic notations with empirical spectrographic data in linguistic research.[27] Advancements in the 1950s included integration with speech synthesis tools, such as the Pattern Playback developed at Haskins Laboratories around 1950, which converted spectrographic patterns back into audible sound, advancing synthetic speech production.[27] The Sona-Graph's portability relative to wartime prototypes and its adoption in fields like phonetics and bioacoustics—exemplified by its use in visualizing bird vocalizations—expanded spectrographic analysis beyond wartime cryptanalysis to civilian studies of animal communication and human audition training for the hearing impaired.[32][33] By the 1960s, early digital implementations emerged alongside analog refinements, with three-dimensional sonagrams providing volumetric representations of frequency, time, and amplitude to capture signal strength more intuitively.[34] Military adaptations persisted, as AT&T modified spectrographic techniques for the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) in underwater acoustics, processing hydrophone data to track submarines via time-frequency displays.[35] These developments laid groundwork for computational spectrography, though analog devices like the Kay Sona-Graph dominated until efficient digital algorithms proliferated later.[31]Generation Techniques

Short-Time Fourier Transform

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) generates a time-frequency representation by computing the Fourier transform of short, overlapping segments of a non-stationary signal, enabling analysis of how frequency content evolves over time.[36] In practice, the signal is divided into frames using a sliding window, each frame is multiplied by a window function to minimize edge effects, and the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) or fast Fourier transform (FFT) is applied to yield complex-valued coefficients for each time step and frequency bin.[37] The resulting two-dimensional array, when taking the squared magnitude, produces the spectrogram, which displays signal power as a function of time and frequency.[38] For a discrete-time signal , the STFT at time index and frequency index is given by where is the window length, is the window function (e.g., Hamming or Hann with length ), and is the hop size determining overlap (typically to for 50–75% overlap to enhance temporal smoothness and reconstruction fidelity).[39] Overlap reduces artifacts from abrupt frame transitions and improves spectrogram continuity, as non-overlapping windows can introduce discontinuities in the time domain that manifest as streaking in the frequency domain.[3] Window choice trades off frequency resolution (longer windows yield narrower main lobes in the frequency domain) against time localization; for instance, a 256-sample Hann window provides moderate resolution suitable for audio signals sampled at 44.1 kHz, balancing leakage suppression with computational efficiency via the FFT.[4] Implementation often involves zero-padding frames to the next power of two for efficient FFT computation, with the spectrogram plotted using decibel scaling of to emphasize dynamic range.[11] Parameter selection—window length from 20–100 ms for speech, hop sizes of 10 ms—depends on the signal's characteristics, as shorter windows capture transients better but broaden frequency estimates due to the inherent time-frequency uncertainty.[10] In digital signal processing libraries like MATLAB'sstft function, default settings use Kaiser windows with high overlap for analytic applications, ensuring invertibility under the constant overlap-add (COLA) condition where the window satisfies .[36]