Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Seasonal affective disorder

View on Wikipedia

| Seasonal affective disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Seasonal mood disorder, depressive disorder with seasonal pattern, winter depression, winter blues, January blues, summer depression, seasonal depression |

| |

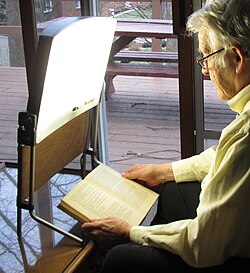

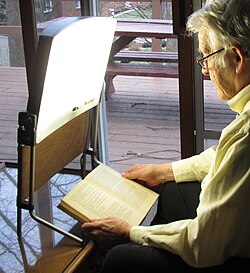

| Bright light therapy is a common treatment for seasonal affective disorder and for circadian rhythm sleep disorders. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a mood disorder subset in which people who typically have normal mental health throughout most of the year exhibit depressive symptoms at the same time each year.[1][2] It is commonly, but not always, associated with the reductions or increases in total daily sunlight hours that occur during the winter or summer.

Common symptoms include sleeping too much, having little to no energy, and overeating.[3] The condition in the summer can include heightened anxiety.[4] However, there are significant differences in the duration, severity, and symptoms of each individual's experience of SAD. For instance, in a fifth of patients, the disorder completely resolves in five to eleven years, whereas for 33–44% of patients, it progresses into non-seasonal major depression.[5]

In the DSM-IV and DSM-5, its status as a standalone condition was changed: It is no longer classified as a unique mood disorder but is now a specifier (called "with seasonal pattern") for recurrent major depressive disorder that occurs at a specific time of the year and fully remits otherwise.[6] Although experts were initially skeptical, the condition eventually became recognized as a common disorder.[7][additional citation(s) needed] However, the validity of SAD was called into question by a 2016 analysis from the Centers for Disease Control, when it found no links between depression, seasonality or sunlight exposure.[8]

In the United States, the percentage of the population affected by SAD ranges from 1.4% of the population in Florida to 9.9% in Alaska.[9]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]SAD is a type of major depressive disorder, and those with the condition may exhibit any of the associated symptoms, such as feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness, thoughts of suicide, loss of interest in activities, withdrawal from social interaction, sleep and appetite problems, difficulty with concentrating and making decisions, decreased libido, a lack of energy, or agitation.[4] Symptoms of winter SAD often include falling asleep earlier or in less than 5 minutes in the evening, oversleeping or difficulty waking up in the morning, nausea, and a tendency to overeat, often with a craving for carbohydrates, which leads to weight gain.[10] SAD is typically associated with winter depression, but springtime lethargy or other seasonal mood patterns are not uncommon.[11] Although each individual case is different, in contrast to winter SAD, people who experience spring and summer depression may be more likely to show symptoms such as insomnia, decreased appetite and weight loss, and agitation or anxiety.[4]

Bipolar disorder

[edit]With seasonal pattern is a specifier for bipolar and related disorders, including bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder.[6] Most people with SAD experience major depressive disorder, but as many as 20% may have a bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorder is characterized by alternating episodes of depression and mania or hypomania. Depressive episodes include symptoms such as low energy, difficulty concentrating, changes in sleep and appetite, feelings of hopelessness, and suicidal thoughts. Manic episodes, which are more common in bipolar I disorder, may include elevated mood, decreased need for sleep, impulsivity, and increased activity or risky behaviors. In contrast, hypomania (seen in bipolar II disorder) presents as a milder form of mania without significant impairment in daily life.[12] It is important to distinguish between diagnoses because there are important treatment differences.[13] In these cases, people who have the With seasonal pattern specifier may experience a depressive episode either due to major depressive disorder or as part of bipolar disorder during the winter and remit in the summer.[6] Around 25% of patients with bipolar disorder may present with a depressive seasonal pattern, which is associated with bipolar II disorder, rapid cycling, eating disorders, and more depressive episodes.[14] Differences in biological sex display distinct clinical characteristics associated to seasonal pattern: males present with more Bipolar II disorder and a higher number of depressive episodes, and females with rapid cycling and eating disorders.[14]

ADHD

[edit]A study by the National Institute of Health published findings in 2016 that concluded, "seasonal and circadian rhythm disturbances are significantly associated with ADHD symptoms." Participants in the study who had ADHD were three times more likely to have SAD symptoms (9.9% vs 3.3%), and about 2.7 times more likely to have s-SAD symptoms (12.5% vs 4.6%).[15] Those with ADHD and SAD are likely to experience sluggishness, irritability, and withdrawal.[16] A study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that approximately 27% of adults with ADHD also experience SAD, with women being more susceptible than men.[17]

Cause

[edit]In many species, activity is diminished during the winter months, in response to the reduction in available food, the reduction of sunlight (especially for diurnal animals), and the difficulties of surviving in cold weather. Hibernation is an extreme example, but even species that do not hibernate often exhibit changes in behavior during the winter.[18]

Various proximate causes have been proposed. One possibility is that SAD is related to a lack of serotonin, and serotonin polymorphisms could play a role in SAD,[19] although this has been disputed.[20] Mice incapable of turning serotonin into N-acetylserotonin (by serotonin N-acetyltransferase) appear to express "depression-like" behavior, and antidepressants such as fluoxetine increase the amount of the enzyme serotonin N-acetyltransferase, resulting in an antidepressant-like effect.[21] Another theory is that the cause may be related to melatonin, which is produced in dim light and darkness by the pineal gland,[22] since there are direct connections, via the retinohypothalamic tract and the suprachiasmatic nucleus, between the retina and the pineal gland.[23][citation needed] Melatonin secretion is controlled by the endogenous circadian clock, but can also be suppressed by bright light.[22]

One study looked at whether some people could be predisposed to SAD based on personality traits. Correlations between certain personality traits such as higher levels of neuroticism, agreeableness, openness, and an avoidance-oriented coping style, appeared to be common in those with SAD.[1]

Per Pfizer, risk factors for SAD include being a female, younger age, previously being diagnosed with extreme depression or bipolar disorder, having a family history of the same disease, or living a considerable distance from the equator.[24]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Seasonal mood variations are believed to be related to light. An argument for this view is the effectiveness of bright-light therapy.[25] SAD is measurably present at latitudes in the Arctic region, such as northern Finland (around 64 degrees north latitude), where the rate of SAD is 9.5%.[26] Cloud cover may contribute to the negative effects of SAD.[27] There is evidence that many patients with SAD have a delay in their circadian rhythm, and that bright light treatment corrects these delays which may be responsible for the improvement in patients.[22]

The symptoms of it mimic those of dysthymia or even major depressive disorder. There is also potential risk of suicide in some patients experiencing SAD. One study reports 6–35% of people with the condition required hospitalization during one period of illness.[27] At times, patients may not feel depressed, but rather lack energy to perform everyday activities.[25]

Subsyndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder (s-SAD or SSAD) is a milder form of SAD experienced by an estimated 14.3% (vs. 6.1% SAD) of the U.S. population.[28] The blue feeling experienced by both those with SAD and with SSAD can usually be dampened or extinguished by exercise and increased outdoor activity, particularly on sunny days, resulting in increased solar exposure.[29] Connections between human mood, as well as energy levels, and the seasons are well documented, even in healthy individuals.[30]

Diagnosis

[edit]According to the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria,[31] Seasonal Affective Disorder is not regarded as a separate disorder. It is called a "course specifier" and may be applied as an added description to the pattern of major depressive episodes in patients with major depressive disorder or patients with bipolar disorder.

The "Seasonal Pattern Specifier" must meet four criteria: depressive episodes at a particular time of the year; remissions or mania/hypomania at a characteristic time of year; these patterns must have lasted two years with no nonseasonal major depressive episodes during that same period; and these seasonal depressive episodes outnumber other depressive episodes throughout the patient's lifetime. The Mayo Clinic describes three types of SAD, each with its own set of symptoms.[4]

Management

[edit]Treatments for classic (winter-based) seasonal affective disorder include light therapy, medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and carefully timed supplementation[32] of the hormone melatonin.[33]

Light therapy

[edit]Photoperiod-related alterations of the duration of melatonin secretion may affect the seasonal mood cycles of SAD. This suggests that light therapy may be an effective treatment for SAD.[34] Light therapy uses a lightbox, which emits far more lumens than a customary incandescent lamp. Bright white "full spectrum" light at 10,000 lux, blue light at a wavelength of 480nm at 2,500 lux or green (actually cyan or blue-green[35]) light at a wavelength of 500nm at 350 lux are used, with the first-mentioned historically preferred.[36][37]

Bright light therapy is effective[28] with the patient sitting a prescribed distance, commonly 30–60 cm, in front of the box with their eyes open, but not staring at the light source,[26] for 30–60 minutes. A study published in May 2010 suggests that the blue light often used for SAD treatment should perhaps be replaced by green or white illumination.[38] Discovering the best schedule is essential. One study has shown that up to 69% of patients find lightbox treatment inconvenient, and as many as 19% stop use because of this.[26]

Dawn simulation has also proven to be effective; in some studies, there is an 83% better response when compared to other bright light therapy.[26] When compared in a study to negative air ionization, bright light was shown to be 57% effective vs. dawn simulation 50%.[39] Patients using light therapy can experience improvement during the first week, but increased results are evident when continued throughout several weeks.[26] Certain symptoms like hypersomnia, early insomnia, social withdrawal, and anxiety resolve more rapidly with light therapy than with cognitive behavioral therapy.[40] Most studies have found it effective without use year round, but rather as a seasonal treatment lasting for several weeks, until frequent light exposure is naturally obtained.[25]

Light therapy can also consist of exposure to sunlight, either by spending more time outside[41] or using a computer-controlled heliostat to reflect sunlight into the windows of a home or office.[42][43] Although light therapy is the leading treatment for seasonal affective disorder, prolonged direct sunlight or artificial lights that don't block the ultraviolet range should be avoided, due to the threat of skin cancer.[44]

The evidence base for light therapy as a preventive treatment for seasonal affective disorder is limited.[45] The decision to use light therapy to treat people with a history of winter depression before depressive symptoms begin should be based on a person's preference of treatment.[45]

Medication

[edit]SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) antidepressants have proven effective in treating SAD.[27] Effective antidepressants are fluoxetine, sertraline, or paroxetine.[25][46] Both fluoxetine and light therapy are 67% effective in treating SAD, according to direct head-to-head trials conducted during the 2006 Can-SAD study.[47] Subjects using the light therapy protocol showed earlier clinical improvement, generally within one week of beginning the clinical treatment.[25] Bupropion extended-release has been shown to prevent SAD for one in four people, but has not been compared directly to other preventive options in trials.[48] In a 2021 updated Cochrane review of second-generation antidepressant medications for the treatment of SAD, a definitive conclusion could not be drawn, due to lack of evidence, and the need for larger randomized controlled trials.[49]

Modafinil may be an effective and well-tolerated treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression.[50]

Another explanation is that vitamin D levels are too low when people do not get enough Ultraviolet-B on their skin. An alternative to using bright lights is to take vitamin D supplements.[51][52][53] However, studies did not show a link between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in elderly Chinese,[54] nor among elderly British women given only 800IU when 6,000IU is needed.[55] 5-HTP (an amino acid that helps to produce serotonin, and is often used to help those with depression) has also been suggested as a supplement that may help treat the symptoms of SAD, by lifting mood, and regulating sleep schedule for those with the condition.[56] However, those who take antidepressants are not advised to take 5-HTP, as antidepressant medications may combine with the supplement to create dangerously high levels of serotonin – potentially resulting in serotonin syndrome.[57]

Other treatments

[edit]Depending upon the patient, one treatment (e.g., lightbox) may be used in conjunction with another (e.g., medication).[25]

Physical exercise has shown to be an effective form of depression therapy, particularly when in addition to another form of treatment for SAD.[58] One particular study noted marked effectiveness for treatment of depressive symptoms, when combining regular exercise with bright light therapy.[59] Patients exposed to exercise which had been added to their treatments in 20 minutes intervals on the aerobic bike during the day, along with the same amount of time underneath the UV light were seen to make a quick recovery.[60]

Of all the psychological therapies aimed at the prevention of SAD, cognitive-behavior therapy, typically involving thought records, activity schedules and a positive data log, has been the subject of the most empirical work. However, evidence for cognitive behavioral therapy or any of the psychological therapies aimed at preventing SAD remains inconclusive.[61]

Epidemiology

[edit]Nordic countries

[edit]Winter depression is a common slump in the mood of some inhabitants of most of the Nordic countries. Iceland, however, seems to be an exception. A study of more than 2000 people there found the prevalence of seasonal affective disorder and seasonal changes in anxiety and depression to be unexpectedly low in both sexes.[62] The study's authors suggested that propensity for SAD may differ due to some genetic factor within the Icelandic population. A study of Canadians of wholly Icelandic descent also showed low levels of SAD.[63] It has more recently been suggested that this may be attributed to the large amount of fish traditionally eaten by Icelandic people. In 2007, about 90 kilograms of fish per person was consumed per year in Iceland, as opposed to about 24 kilograms in the US and Canada,[64] rather than to genetic predisposition; a similar anomaly is noted in Japan, where annual fish consumption in recent years averages about 60 kilograms per capita.[65] Fish are high in vitamin D. Fish also contain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which helps with a variety of neurological dysfunctions.[66][dubious – discuss]

Other countries

[edit]In the United States, a diagnosis of seasonal affective disorder was first proposed by Norman E. Rosenthal, M.D. in 1984. Rosenthal wondered why he became sluggish during the winter after moving from sunny South Africa to (cloudy in winter) New York. He started experimenting with increasing exposure to artificial light, and found this made a difference. In Alaska it has been established that there is a SAD rate of 8.9%, and an even greater rate of 24.9%[67] for subsyndromal SAD.

Around 20% of Irish people are affected by SAD, according to a survey conducted in 2007. The survey also shows women are more likely to be affected by SAD than men.[68][better source needed] An estimated 3% of the population in the Netherlands experience winter SAD.[69]

History

[edit]SAD was formally described and named in 1984 by Norman E. Rosenthal and his colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health.[70][71] The initial investigation was motivated by observations of depression occurring during the dark winter months in northern regions of the United States, known as polar night. Rosenthal proposed that the reduction in available natural light during winter could contribute to this phenomenon. Subsequently, he and his colleagues conducted a placebo-controlled study that utilized light therapy to document the effects of the condition.[70][71] Although Rosenthal's ideas were initially greeted with skepticism, SAD has become well recognized. His 1993 book Winter Blues[72] has become the standard introduction to the subject.[73]

Research on SAD in the United States began in 1979 when Herb Kern, a research engineer, noticed he felt depressed during the winter months. Kern suspected that scarcer natural light in winter was the cause and discussed the idea with NIMH scientists working on bodily rhythms. They were intrigued and responded by inventing a lightbox to treat Kern's depression, which improved.[71][74]

SAD is usually more common in the fall/winter (Winter SAD), though it may occur during the spring/summer (Spring SAD). Winter-onset SAD is more common and is often characterized by atypical depressive symptoms including hypersomnia, increased appetite, and craving for carbohydrates. Spring/summer SAD is also seen and is more frequently associated with typical depressive symptoms including insomnia and loss of appetite.[75]

Criticism of disorder and diagnosis

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2025) |

The validity of SAD has been called into question multiple times. A 2008 study indicated that some people stay without sun for months, yet they are not affected by SAD.[76] A 2016 analysis from the Centers for Disease Control found no links between depression, seasonality or sunlight exposure and suggested discontinuation of the diagnosis. Further, a 2018 study focusing on instability of SAD diagnosis criteria over prolonged periods of time, suggested that SAD is a temporary expression of a mood disorder rather than a specific disorder.[8][77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Oginska H, Oginska-Bruchal K (May 2014). "Chronotype and personality factors of predisposition to seasonal affective disorder". Chronobiology International. 31 (4): 523–31. doi:10.3109/07420528.2013.874355. PMID 24397301. S2CID 22428871.

- ^ Ivry, Sara (August 13, 2002). Seasonal Depression can Accompany Summer Sun. The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008

- ^ MedlinePlus Overview seasonalaffectivedisorder

- ^ a b c d Seasonal affective disorder (SAD): Symptoms. MayoClinic.com (September 22, 2011). Retrieved on March 24, 2013.

- ^ Nussbaumer-Streit, Barbara; Pjrek, Edda; Kien, Christina; Gartlehner, Gerald; Bartova, Lucie; Friedrich, Michaela-Elena; Kasper, Siegfried; Winkler, Dietmar (November 26, 2018). "Implementing prevention of seasonal affective disorder from patients' and physicians' perspectives – a qualitative study". BMC Psychiatry. 18 (1): 372. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1951-0. ISSN 1471-244X. PMC 6260561. PMID 30477472.

- ^ Friedman, Richard A. (December 18, 2007) Brought on by Darkness, Disorder Needs Light. New York Times.

- ^ a b Traffanstedt M, Mehta S, LoBello S (2016). "Major Depression With Seasonal Variation: Is It a Valid Construct?". Clinical Psychological Science. 4 (5): 825–834. doi:10.1177/2167702615615867. S2CID 43574728.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2014). Abnormal Psychology (6th ed.). New York, New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-259-06072-4.

- ^ Partonen T, Lönnqvist J (October 1998). "Seasonal affective disorder". Lancet. 352 (9137): 1369–74. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(98)01015-0. PMID 9802288. S2CID 42760726.

- ^ "What is SAD (Seasonal Affective Disorder)?". Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ "Bipolar Disorders". www.psychiatry.org. Retrieved April 3, 2025.

- ^ "Depression" (PDF). Mood Disorders Society of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ a b Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Scott J, Boudebesse C, Lajnef M, Gard S, Kahn JP, Azorin JM, Henry C, Leboyer M, Etain B (November 2013). "Bipolar disorder with seasonal pattern: clinical characteristics and gender influences". Chronobiology International. 30 (9): 1101–7. doi:10.3109/07420528.2013.800091. PMC 5225270. PMID 23931033.

- ^ Wynchank, Dora S.; Bijlenga, Denise; Lamers, Femke; Bron, Tannetje I.; Winthorst, Wim H.; Vogel, Suzan W.; Penninx, Brenda W.; Beekman, Aartjan T.; Kooij, J. Sandra (October 10, 2016). "ADHD, circadian rhythms and seasonality". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 81: 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.06.018. ISSN 1879-1379. PMID 27423070.

- ^ Team, ADDA Editorial (November 30, 2023). "Beat the Blues! Tips for ADHD and Seasonal Affective Disorder". ADDA - Attention Deficit Disorder Association. Retrieved March 13, 2025.

- ^ "Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". December 23, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Nesse RM, Williams GC (1996). Why We Get Sick (First ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-8129-2224-0.

- ^ Johansson C, Smedh C, Partonen T, Pekkarinen P, Paunio T, Ekholm J, Peltonen L, Lichtermann D, Palmgren J, Adolfsson R, Schalling M (April 2001). "Seasonal affective disorder and serotonin-related polymorphisms". Neurobiology of Disease. 8 (2): 351–7. doi:10.1006/nbdi.2000.0373. PMID 11300730. S2CID 10841651.

- ^ Johansson C, Willeit M, Levitan R, Partonen T, Smedh C, Del Favero J, Bel Kacem S, Praschak-Rieder N, Neumeister A, Masellis M, Basile V, Zill P, Bondy B, Paunio T, Kasper S, Van Broeckhoven C, Nilsson LG, Lam R, Schalling M, Adolfsson R (July 2003). "The serotonin transporter promoter repeat length polymorphism, seasonal affective disorder and seasonality". Psychological Medicine. 33 (5): 785–92. doi:10.1017/S0033291703007372. PMID 12877393. S2CID 45837170.

- ^ Uz T, Manev H (April 2001). "Prolonged swim-test immobility of serotonin N-acetyltransferase (AANAT)-mutant mice". Journal of Pineal Research. 30 (3): 166–70. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079X.2001.300305.x. PMID 11316327. S2CID 24360614.

- ^ a b c Lam RW, Levitan RD (November 2000). "Pathophysiology of seasonal affective disorder: a review". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 25 (5): 469–80. PMC 1408021. PMID 11109298.

- ^ Arendt, Josephine; Aulinas, Anna (2000), Feingold, Kenneth R.; Anawalt, Bradley; Blackman, Marc R.; Boyce, Alison (eds.), "Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin", Endotext, South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc., PMID 31841296, retrieved March 13, 2025

- ^ "Shedding Light on Seasonal Affective Disorder | Pfizer". www.pfizer.com. Retrieved March 13, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Michalak EE, Tam EM (May 2006). "The Can-SAD study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (5): 805–12. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.805. PMID 16648320.

- ^ a b c d e Avery DH, Eder DN, Bolte MA, Hellekson CJ, Dunner DL, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN (August 2001). "Dawn simulation and bright light in the treatment of SAD: a controlled study". Biological Psychiatry. 50 (3): 205–16. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01200-8. PMID 11513820. S2CID 21123296.

- ^ a b c Modell JG, Rosenthal NE, Harriett AE, Krishen A, Asgharian A, Foster VJ, Metz A, Rockett CB, Wightman DS (October 2005). "Seasonal affective disorder and its prevention by anticipatory treatment with bupropion XL". Biological Psychiatry. 58 (8): 658–67. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.021. PMID 16271314. S2CID 25662514.

- ^ a b Avery DH, Kizer D, Bolte MA, Hellekson C (April 2001). "Bright light therapy of subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder in the workplace: morning vs. afternoon exposure". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 103 (4): 267–74. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00078.x. PMID 11328240. S2CID 1342943.

- ^ Leppämäki S, Haukka J, Lönnqvist J, Partonen T (August 2004). "Drop-out and mood improvement: a randomised controlled trial with light exposure and physical exercise [ISRCTN36478292]". BMC Psychiatry. 4 22. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-22. PMC 514552. PMID 15306031.

- ^ Partonen T, Lönnqvist J (2000). "Bright light improves vitality and alleviates distress in healthy people". Journal of Affective Disorders. 57 (1–3): 55–61. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(99)00063-4. PMID 10708816.

- ^ Gabbard GO. Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 1296.

- ^ Bhattacharjee Y (September 2007). "Psychiatric research. Is internal timing key to mental health?". Science. 317 (5844): 1488–90. doi:10.1126/science.317.5844.1488. PMID 17872420. S2CID 71387673.

- ^ "Properly Timed Light, Melatonin Lift Winter Depression by Syncing Rhythms". NIMH Science News. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). May 1, 2006. Archived from the original on April 27, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Howland RH (January 2009). "Somatic therapies for seasonal affective disorder". Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 47 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3928/02793695-20090101-07. PMID 19227105.

- ^ Jones AZ (February 15, 2012). "The Visible Light Spectrum". Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ Loving RT, Kripke DF, Knickerbocker NC, Grandner MA (November 2005). "Bright green light treatment of depression for older adults [ISRCTN69400161]". BMC Psychiatry. 5 42. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-5-42. PMC 1309618. PMID 16283926.

Bright green light was not shown to have an antidepressant effect in the age group of this study, but a larger trial with brighter green light might be of value.

- ^ Strong RE, Marchant BK, Reimherr FW, Williams E, Soni P, Mestas R (2009). "Narrow-band blue-light treatment of seasonal affective disorder in adults and the influence of additional nonseasonal symptoms". Depression and Anxiety. 26 (3): 273–8. doi:10.1002/da.20538. PMID 19016463. S2CID 40649124.

- ^ Gooley JJ, Rajaratnam SM, Brainard GC, Kronauer RE, Czeisler CA, Lockley SW (May 2010). "Spectral responses of the human circadian system depend on the irradiance and duration of exposure to light". Science Translational Medicine. 2 (31): 31ra33. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000741. PMC 4414925. PMID 20463367.

- ^ Terman M, Terman JS (December 2006). "Controlled trial of naturalistic dawn simulation and negative air ionization for seasonal affective disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (12): 2126–2133. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2126. PMID 17151164.

- ^ Meyerhoff J, Young MA, Rohan KJ (May 2018). "Patterns of depressive symptom remission during the treatment of seasonal affective disorder with cognitive-behavioral therapy or light therapy". Depression and Anxiety. 35 (5): 457–467. doi:10.1002/da.22739. PMC 5934317. PMID 29659120.

- ^ Beck M (December 1, 2009). "Exercise outdoors: Bright Ideas for Treating the Winter Blues". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Applications: Health". Practical Solar. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ "Grab the Sun With Heliostats". New York House. June 1, 2009. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ Osborn J, Raetz J, Kost A (September 2014). "Seasonal affective disorder, grief reaction, and adjustment disorder". The Medical Clinics of North America. 98 (5): 1065–77. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2014.06.006. PMID 25134873.

- ^ a b Nussbaumer-Streit B, Forneris CA, Morgan LC, Van Noord MG, Gaynes BN, Greenblatt A, et al. (March 2019). "Light therapy for preventing seasonal affective disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (4) CD011269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011269.pub3. PMC 6422319. PMID 30883670.

- ^ Moscovitch A, Blashko CA, Eagles JM, Darcourt G, Thompson C, Kasper S, Lane RM (February 2004). "A placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the treatment of outpatients with seasonal affective disorder". Psychopharmacology. 171 (4): 390–397. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1594-8. PMID 14504682. S2CID 683231.

- ^ Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Michalak EE, Tam EM (May 2006). "The Can-SAD study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 163 (5): 805–812. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.805. PMID 16648320.

- ^ Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, Gaynes BN, Forneris CA, Morgan LC, Greenblatt A, et al. (March 2019). "Second-generation antidepressants for preventing seasonal affective disorder in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (4) CD011268. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011268.pub3. PMC 6422318. PMID 30883669.

- ^ Nussbaumer-Streit B, Thaler K, Chapman A, Probst T, Winkler D, Sönnichsen A, et al. (March 2021). "Second-generation antidepressants for treatment of seasonal affective disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (3) CD008591. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008591.pub3. PMC 8092631. PMID 33661528.

- ^ Lundt L (August 2004). "Modafinil treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression: an open-label pilot study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 81 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00162-9. PMID 15306145.

- ^ Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, Birge SJ, Morris JC (December 2006). "Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (12): 1032–40. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000240986.74642.7c. PMID 17138809. S2CID 19008379.

- ^ Lansdowne AT, Provost SC (February 1998). "Vitamin D3 enhances mood in healthy subjects during winter". Psychopharmacology. 135 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/s002130050517. PMID 9539254. S2CID 21227712.

- ^ Gloth FM, Alam W, Hollis B (1999). "Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 3 (1): 5–7. PMID 10888476.

- ^ Pan A, Lu L, Franco OH, Yu Z, Li H, Lin X (November 2009). "Association between depressive symptoms and 25-hydroxyvitamin D in middle-aged and elderly Chinese". Journal of Affective Disorders. 118 (1–3): 240–3. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.02.002. PMID 19249103.

- Lay summary in: "Vitamin D May Not Be The Answer To Feeling SAD". Science Daily (Press release). March 18, 2009.

- ^ Dumville JC, Miles JN, Porthouse J, Cockayne S, Saxon L, King C (2006). "Can vitamin D supplementation prevent winter-time blues? A randomised trial among older women". The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 10 (2): 151–3. PMID 16554952.

- ^ "Don't be SAD: seasonal affective disorder advice". medino. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "5-HTP Safety Concerns". www.poison.org. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ Pinchasov BB, Shurgaja AM, Grischin OV, Putilov AA (April 2000). "Mood and energy regulation in seasonal and non-seasonal depression before and after midday treatment with physical exercise or bright light". Psychiatry Research. 94 (1): 29–42. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(00)00138-4. PMID 10788675. S2CID 12731381.

- ^ Leppämäki S, Partonen T, Lönnqvist J (November 2002). "Bright-light exposure combined with physical exercise elevates mood". Journal of Affective Disorders. 72 (2): 139–44. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00417-7. PMID 12200204.

- ^ Roecklein KA, Rohan KJ (January 2005). "Seasonal affective disorder: an overview and update". Psychiatry. 2 (1): 20–6. PMC 3004726. PMID 21179639.

- ^ Forneris, Catherine A.; Nussbaumer-Streit, Barbara; Morgan, Laura C.; Greenblatt, Amy; Van Noord, Megan G.; Gaynes, Bradley N.; Wipplinger, Jörg; Lux, Linda J.; Winkler, Dietmar; Gartlehner, Gerald (May 24, 2019). "Psychological therapies for preventing seasonal affective disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5) CD011270. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011270.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6533196. PMID 31124141.

- ^ Magnusson A, Axelsson J, Karlsson MM, Oskarsson H (February 2000). "Lack of seasonal mood change in the Icelandic population: results of a cross-sectional study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (2): 234–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.234. PMID 10671392. S2CID 20441380.

- ^ Magnússon A, Axelsson J (December 1993). "The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder is low among descendants of Icelandic emigrants in Canada". Archives of General Psychiatry. 50 (12): 947–51. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240031004. PMID 8250680.

- ^ Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics: SECTION 2 – Food balance sheets and fish contribution to protein supply, by country from 1961 to 2007 . Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2008)

- ^ Cott J, Hibbeln JR (February 2001). "Lack of seasonal mood change in Icelanders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (2): 328. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.328. PMID 11156835.

- ^ Horrocks LA, Yeo YK (September 1999). "Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)". Pharmacological Research. 40 (3): 211–25. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.6891. doi:10.1006/phrs.1999.0495. PMID 10479465.

- ^ SAD Treatment | SAD Lamp | SAD Light | SAD Cure | Seasonal Affected Disorder Britebox Energise Case Study Archived August 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Britebox.co.uk. Retrieved on March 24, 2013.

- ^ One in five suffers from SAD. Irish Examiner (November 10, 2007). Retrieved on March 24, 2013.

- ^ Mersch PP, Middendorp HM, Bouhuys AL, Beersma DG, van den Hoofdakker RH (April 1999). "The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder in The Netherlands: a prospective and retrospective study of seasonal mood variation in the general population" (PDF). Biol. Psychiatry. 45 (8): 1013–22. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00220-0. hdl:11370/31c5324d-4415-4980-9fb0-cd8f3b700b77. PMID 10386184. S2CID 21467329.

- ^ a b Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, Mueller PS, Newsome DA, Wehr TA (January 1984). "Seasonal affective disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy". Archives of General Psychiatry. 41 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010. PMC 2686645. PMID 6581756.

- ^ a b c Marshall, Fiona. Cheevers, Peter (2003). "Positive options for Seasonal Affective Disorder", p. 77. Hunter House, Alameda, Calif. ISBN 0-89793-413-X.

- ^ Rosenthal NE (2006). Winter Blues: Everything You Need to Know to Beat Seasonal Affective Disorder (Revised ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-214-6.

- ^ More LK (December 26, 1994). "It's Wintertime: When Winter Falls, Many Find Themselves In Need Of Light". Milwaukee Sentinel. Gannett News Service.

- ^ Ban TA (2011). Gershon S (ed.). An Oral History of Neuropsychopharmacology, The First Fifty Years, Peer Interviews. Vol. 5. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology.[page needed]

- ^ "Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD): Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". December 23, 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hansen, Vidje; Skre, Ingunn; Lund, Eiliv (June 2008). "What is this thing called "SAD"? A critique of the concept of seasonal affective disorder". Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale. 17 (2): 120–127. doi:10.1017/s1121189x00002815. ISSN 1121-189X.

- ^ Cléry-Melin, Marie-Laure; Gorwood, Philip; Friedman, Serge; Even, Christian (February 2018). "Stability of the diagnosis of seasonal affective disorder in a long-term prospective study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 227: 353–357. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.014. PMID 29145077.