Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

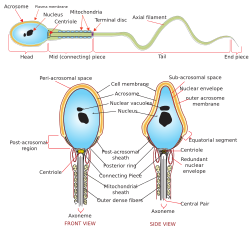

Acrosome

View on Wikipedia

The acrosome is an organelle that develops over the anterior (front) half of the head in the spermatozoa (sperm cells) of humans and many other animals. It is a cap-like structure derived from the Golgi apparatus. In placental mammals, the acrosome contains degradative enzymes (including hyaluronidase and acrosin).[1] These enzymes break down the outer membrane of the ovum,[2] called the zona pellucida, allowing the haploid nucleus in the sperm cell to join with the haploid nucleus in the ovum. This shedding of the acrosome, known as the acrosome reaction, can be stimulated in vitro by substances that a sperm cell may encounter naturally, such as progesterone[3] or follicular fluid, as well as the more commonly used calcium ionophore A23187.[4] This can be done to serve as a positive control when assessing the acrosome reaction of a sperm sample by flow cytometry[5] or fluorescence microscopy. This is usually done after staining with a fluoresceinated lectin such as FITC-PNA, FITC-PSA, FITC-ConA, or fluoresceinated antibody such as FITC-CD46.[6]

In the case of globozoospermia (sperm with round heads), the Golgi apparatus is not transformed into the acrosome, causing male infertility.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "acrosome definition - Dictionary - MSN Encarta". Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ Larson, Jennine L.; Miller, David J. (1999). "Simple histochemical stain for acrosomes on sperm from several species". Molecular Reproduction and Development. 52 (4): 445–449. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199904)52:4<445::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-6. ISSN 1098-2795. PMID 10092125. S2CID 24542696.

- ^ Lishko, Polina V.; Botchkina, Inna L.; Kirichok, Yuriy (March 2011). "Progesterone activates the principal Ca 2+ channel of human sperm". Nature. 471 (7338): 387–391. Bibcode:2011Natur.471..387L. doi:10.1038/nature09767. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 21412339. S2CID 4340309.

- ^ Jamil, K.; White, I. G. (December 1981). "Induction of acrosomal reaction in sperm with ionophore A23187 and calcium". Archives of Andrology. 7 (4): 283–292. doi:10.3109/01485018108999319. ISSN 0148-5016. PMID 6797354.

- ^ Miyazaki R, Fukuda M, Takeuchi H, Itoh S, Takada M (1990). "Flow cytometry to evaluate acrosome-reacted sperm". Arch. Androl. 25 (3): 243–51. doi:10.3109/01485019008987613. PMID 2285347.

- ^ Carver-Ward JA, Moran-Verbeek IM, Hollanders JM (February 1997). "Comparative flow cytometric analysis of the human sperm acrosome reaction using CD46 antibody and lectins". J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 14 (2): 111–9. doi:10.1007/bf02765780. PMC 3454831. PMID 9048242.

- ^ Hermann Behre; Eberhard Nieschlag (2000). Andrology : Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction. Berlin: Springer. p. 155. ISBN 3-540-67224-9.