Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

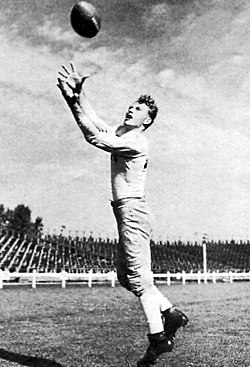

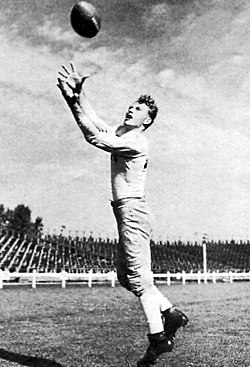

Wide receiver

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

A wide receiver (WR), also referred to as a wideout, and historically known as a split end (SE) or flanker (FL), is an eligible receiver in gridiron football. A key skill position of the offense, WR gets its name from the player being split out "wide" (near the sidelines), farthest away from the rest of the offensive formation.

A forward pass-catching specialist, the wide receiver is one of the fastest players on the field alongside cornerbacks and running backs. One on either extreme of the offensive line is typical, but several may be employed on the same play. A slot receiver lines up between a wide receiver and the offensive line.

Through 2022, only four wide receivers, Jerry Rice (in 1987 and 1993), Michael Thomas (in 2019), Cooper Kupp (in 2021), and Justin Jefferson (in 2022), have won Offensive Player of the Year.[1] In every other year it was awarded to either a quarterback or running back. No wide receiver has ever won MVP. Jerry Rice is the leader in receptions, receiving yards, and touchdowns on the all-time list for receivers, along with being a 3-time Super Bowl champion and 10-time All-Pro selection.

Role

[edit]

The wide receiver's principal role is to catch forward passes from the quarterback. On passing plays, the receiver attempts to avoid, outmaneuver, or simply outrun the cornerbacks or safeties typically defending them. If the receiver becomes open on their pass route, the quarterback may throw a pass to them. The receiver needs to successfully catch the ball without it touching the ground (known as a completion) and then run with the ball as far downfield as possible, hoping to reach the end zone to score a touchdown.

Especially fast receivers are typically perceived as "deep threats", while those with good hands and perhaps shifty moves may be regarded as "possession receivers" prized for running crossing routes across the middle of the field, and converting third-down situations. Taller receivers with a height advantage over typically shorter defenders tend to play further to the outside and run deep more often, while shorter ones tend to play inside and run more routes underneath the top of the defense.

A wide receiver may block theirs or another's defender, depending on the type of play being run. On standard running plays they will block their assigned defender for the running back. Particularly in the case of draws and other trick plays, they may run a pass route with the intent of drawing defenders away from the intended action. Well-rounded receivers are noted for skill in both roles; Hines Ward in particular received praise for his blocking abilities while also becoming the Pittsburgh Steelers' all-time leading receiver and one of 13 in NFL history through 2009 with at least 1,000 receptions.[2][3]

Occasionally wide receivers are used to run the ball, usually in plays seeking to surprise the defense, as in an end-around or reverse. All-time NFL receiving yardage leader Jerry Rice also rushed the ball 87 times for 645 yards and 10 touchdowns in his 20 NFL seasons.[4]

In even rarer cases, receivers may pass the ball as part of an outright trick play. Like a running back, a receiver may legally pass the ball so long as they receive it behind the line of scrimmage, in the form of a handoff or backward lateral. In Super Bowl XL, Antwaan Randle El, a four-year quarterback at Indiana University, threw a touchdown pass at the wide receiver position playing for the Pittsburgh Steelers against the Seattle Seahawks, the first wide receiver in Super Bowl history to do so, a feat later accomplished by Jauan Jennings in Super Bowl LVIII.

Wide receivers often also serve on special teams as kick or punt returners, as gunners on coverage teams, or as part of the hands team during onside kicks. Devin Hester, from the Chicago Bears, touted as one of the greatest kick and punt returners of all time, was listed as a wide receiver (after his first season, during which he was listed as a cornerback). Five-time All-Pro and ten-time Pro Bowl member Matthew Slater was a gunner for the New England Patriots who was likewise listed as a wide receiver, however he had only one reception in his career.

In the NFL, wide receivers use the numbers 0–49 and 80–89.

A "route tree" system typically used in high school and college employs numbers zero through nine, with zero being a "go route" and a nine being a "hitch route" or vice versa. In high school they are normally a part of the play call, but are usually disguised in higher levels of plays.[5][clarification needed]

History

[edit]The wide receiver grew out of a position known as the end. Originally, the ends played on the offensive line, immediately next to the tackles, in a position now referred to as the tight end. By the rules governing the forward pass, ends (positioned at the end of the line of scrimmage) and backs (positioned behind the line of scrimmage) are eligible receivers. Most early football teams used the ends sparingly as receivers, as their starting position next to the offensive tackles at the end of the offensive formation often left them in heavy traffic with many defenders around. By the 1930s, some teams were experimenting with spreading the field by moving one end far out near the sideline, drawing the defense away from running plays and leaving them more open on passing ones. These "split ends" became the prototype for what has evolved into being called today the wide receiver. Don Hutson, who played college football at Alabama and professionally with the Green Bay Packers, was the first player to exploit the potential of the split end position.

As the passing game evolved, a second de facto wide receiver was added by employing a running back in a pass-catching role rather than splitting out the "blind-side" end, who was typically retained as a blocker to protect the left side of right-handed quarterbacks. The end stayed at the end of the offensive line in what today is a tight end position, while the running back - who would line up a yard or so off the offensive line and some distance from the end in a "flank" position - became known as a "flanker".

Lining up behind the line of scrimmage gave the flanker two principal advantages. First, a flanker has more "space" between themselves and their opposing defensive cornerback, who can not as easily "jam" them at the line of scrimmage; second, flankers are eligible for motion plays, which allow them to move laterally before and during the snap. Elroy "Crazy Legs" Hirsch is one of the earliest players to successfully exploit the potential of the flanker position as a member of the Los Angeles Rams during the 1950s.

While some teams did experiment with more than two wide receivers as a gimmick or trick play, most teams used the pro set (of a flanker, split end, half back, full back, tight end, and quarterback) as the standard group of ball-handling personnel. An early innovator, coach Sid Gillman used 3+ wide receiver sets as early as the 1960s. In sets that have three, four, or five wide receivers, extra receivers are typically called slot receivers, as they play in the "slot" (open space) between the furthest receiver and the offensive line, typically lining up off the line of scrimmage like a flanker.

The first use of a slot receiver is often credited to Al Davis, a Gillman assistant who took the concept with him as a coach of the 1960s Oakland Raiders. Other members of the Gillman coaching tree, including Don Coryell and John Madden, brought these progressive offensive ideas along with them into the 1970s and early 1980s, but it was not until the 1990s that teams began to reliably use three or more wide receivers, notably the "run and shoot" offense popularized by the Houston Cougars of the NCAA and the Houston Oilers of the NFL, and the "K Gun" offense used by the Buffalo Bills. Charlie Joiner, a member of the "Air Coryell" San Diego Chargers teams of the late 1970s and early 1980s, was the first "slot receiver" to be his team's primary receiver.[citation needed] As NFL teams increasingly "defaulted to three- and four-receiver sets" by the late 2010s, the slot receiver became a fixture of American football formations and the slot cornerback became a de facto starter.[6]

Wide receivers generally hit their peak between the ages of 23 and 30, with about 80 percent of peak seasons falling within that range according to one study.[7]

Types

[edit]The designation for a receiver separated from the main offensive formation varies depending on how far they are removed from it and whether they begin on or off the line of scrimmage. The three principal designations are "wide receiver"/"split end", "flanker", and "slot back":

- Split end (X or SE): A receiver positioned farthest from center on their side of the field which takes their stance on the line of scrimmage, necessary to meet the rule requiring seven players to be lined up on it at the snap. In a punt formation, the split end is known as a gunner.[8]

- Flanker/Flanker back (Z or FL or 6 back): Frequently the team's featured receiver, the flanker lines up a yard or so behind the line of scrimmage, generally on the same side of the formation as a tight end. It is typically the farthest player from the center on its side of the field, and uses the initial buffer between their starting position off the line and a defender to avoid immediate "jamming" (legal defensive contact within five yards of the line of scrimmage). Being a member of the "backfield", the flanker can go into lateral or backward motion before the snap to potentially position themselves for a changing role on the play or simply to confound a defense, and is usually the one to do so.[9]

- Slotback or slot receiver (Y, SB or SR): A receiver lining up in the offensive back field, horizontally positioned between the offensive tackle and the split end or between the tight end and the flanker. Canadian and arena football allow a slotback to take a running start at the line; American football allows the slot receiver to move backward or laterally like a flanker, but not at the same time as any other member of the backfield. They are usually larger players as they need to make catches over the middle. In American football, slot receivers are typically used in flexbone or other triple option offenses, while Canadian football uses three of them in almost all formations (in addition to two split ends and a single running back).

Gameplay

[edit]Wide receivers line up on the offensive side of the ball, typically on the line of scrimmage, and are positioned on the periphery of the formation. They are often split out wide from the offensive line, hence the name "wide" receiver. The primary objective of a wide receiver is to catch passes from the quarterback and gain yardage.

Wide receivers must possess a combination of speed, agility, and hands to excel in their role. They must be able to quickly accelerate off the line of scrimmage, create separation from defenders, and make contested catches in traffic. Additionally, route-running is a critical skill for wide receivers, as they must effectively navigate the field and find open space to receive passes.

Player roles

[edit]Wide receivers are typically categorized into different roles based on their skill sets and playing styles. These roles include:

- Split end: Also known as "X receiver," the split end lines up on the line of scrimmage on the opposite side of the tight end. They are often the primary deep threat in the offense, using their speed to stretch the field vertically.

- Flanker: The flanker, or "Z receiver," lines up off the line of scrimmage, usually on the same side as the tight end. They are versatile players who can excel in various routes, including short and intermediate passes.

- Slot receiver: Slot receivers line up between the offensive line and the split end or flanker. They are often smaller and quicker than outside receivers, making them elusive targets in the passing game. Slot receivers are frequently targeted on short routes and are valuable in getting first downs.

- Blocking receiver: While catching passes is the primary responsibility of wide receivers, some are also proficient blockers. Blocking receivers excel at engaging defenders and creating running lanes for ball carriers. Their blocking prowess is especially valuable on running plays and screen passes.

Strategies

[edit]Wide receivers are involved in various offensive strategies designed to exploit mismatches and create scoring opportunities. Some common strategies include:

- Route combinations: Offensive coordinators design plays with multiple receivers running complementary routes to confuse defenses and create openings in coverage. These route combinations often involve receivers running short, intermediate, and deep routes to attack different areas of the field simultaneously.

- Screen passes: Screen passes involve the quarterback quickly delivering the ball to a receiver behind the line of scrimmage, with blockers in front of them. Wide receivers must use their agility and vision to navigate through traffic and pick up yardage after the catch.

- Play-action: Play-action plays involve the quarterback faking a handoff to a running back before throwing the ball downfield. Wide receivers play a crucial role in selling the play-fake by running convincing routes and drawing defenders away from the intended target.

- Red zone targets: In the red zone, the area inside the opponent's 20-yard line, wide receivers become prime targets for scoring touchdowns. Their ability to win contested catches and find openings in the defense is invaluable in tight spaces near the end zone.

References

[edit]- ^ Hope, Dan (July 7, 2013). "Ranking the Top 25 NFL Offensive Player of the Year Candidates". Bleacher Report. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

The award is typically given to the league's most productive quarterback or running back. Of the 41 times it has been given, it's been won. The exception is San Francisco 49ers wide receiver Jerry Rice, who won the award in both 1987 and 1993

. - ^ "Hines Ward, Pittsburgh Steelers, NFL's dirtiest player, peers say". Sports Illustrated. November 5, 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-11-05.

- ^ "NFL Players Poll: Dirtiest Player". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 2010-03-29.

- ^ "CNN/SI - Jerry Rice". August 18, 2000. Archived from the original on 2000-08-18.

- ^ "WR Basics: Routes and the Passing Tree". Shakin the Southland. SB Nation. March 22, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- ^ "The NFL's 11 best slot defenders". June 1, 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2025.

- ^ "The Peak Age For An NFL Wide Receiver". Apex Fantasy Football Money Leagues. 2021-05-21. Retrieved 2021-05-21.

- ^ "Football 101: The Split End". September 17, 2004. Archived from the original on 2004-09-17.

- ^ "The Flanker/ Slot Receiver". phillyburbs.com. Archived from the original on 2004-09-17.

External links

[edit] Media related to American football wide receivers at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to American football wide receivers at Wikimedia Commons