Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Strength of materials

View on WikipediaThe strength of materials is determined using various methods of calculating the stresses and strains in structural members, such as beams, columns, and shafts. The methods employed to predict the response of a structure under loading and its susceptibility to various failure modes takes into account the properties of the materials such as its yield strength, ultimate strength, Young's modulus, and Poisson's ratio. In addition, the mechanical element's macroscopic properties (geometric properties) such as its length, width, thickness, boundary constraints and abrupt changes in geometry such as holes are considered.

The theory began with the consideration of the behavior of one and two dimensional members of structures, whose states of stress can be approximated as two dimensional, and was then generalized to three dimensions to develop a more complete theory of the elastic and plastic behavior of materials. An important founding pioneer in mechanics of materials was Stephen Timoshenko.

Definition

[edit]In the mechanics of materials, the strength of a material is its ability to withstand an applied load without failure or plastic deformation. The field of strength of materials deals with forces and deformations that result from their acting on a material. A load applied to a mechanical member will induce internal forces within the member called stresses when those forces are expressed on a unit basis. The stresses acting on the material cause deformation of the material in various manners including breaking them completely. Deformation of the material is called strain when those deformations too are placed on a unit basis.

The stresses and strains that develop within a mechanical member must be calculated in order to assess the load capacity of that member. This requires a complete description of the geometry of the member, its constraints, the loads applied to the member and the properties of the material of which the member is composed. The applied loads may be axial (tensile or compressive), or rotational (strength shear). With a complete description of the loading and the geometry of the member, the state of stress and state of strain at any point within the member can be calculated. Once the state of stress and strain within the member is known, the strength (load carrying capacity) of that member, its deformations (stiffness qualities), and its stability (ability to maintain its original configuration) can be calculated.

The calculated stresses may then be compared to some measure of the strength of the member such as its material yield or ultimate strength. The calculated deflection of the member may be compared to deflection criteria that are based on the member's use. The calculated buckling load of the member may be compared to the applied load. The calculated stiffness and mass distribution of the member may be used to calculate the member's dynamic response and then compared to the acoustic environment in which it will be used.

Material strength refers to the point on the engineering stress–strain curve (yield stress) beyond which the material experiences deformations that will not be completely reversed upon removal of the loading and as a result, the member will have a permanent deflection. The ultimate strength of the material refers to the maximum value of stress reached. The fracture strength is the stress value at fracture (the last stress value recorded).

Types of loadings

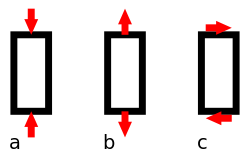

[edit]- Transverse loadings – Forces applied perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of a member. Transverse loading causes the member to bend and deflect from its original position, with internal tensile and compressive strains accompanying the change in curvature of the member.[1] Transverse loading also induces shear forces that cause shear deformation of the material and increase the transverse deflection of the member.

- Axial loading – The applied forces are collinear with the longitudinal axis of the member. The forces cause the member to either stretch or shorten.[2]

- Torsional loading – Twisting action caused by a pair of externally applied equal and oppositely directed force couples acting on parallel planes or by a single external couple applied to a member that has one end fixed against rotation.

Stress terms

[edit]

Uniaxial stress is expressed by

where F is the force acting on an area A.[3] The area can be the undeformed area or the deformed area, depending on whether engineering stress or true stress is of interest.

- Compressive stress (or compression) is the stress state caused by an applied load that acts to reduce the length of the material (compression member) along the axis of the applied load; it is, in other words, a stress state that causes a squeezing of the material. A simple case of compression is the uniaxial compression induced by the action of opposite, pushing forces. Compressive strength for materials is generally higher than their tensile strength. However, structures loaded in compression are subject to additional failure modes, such as buckling, that are dependent on the member's geometry.

- Tensile stress is the stress state caused by an applied load that tends to elongate the material along the axis of the applied load, in other words, the stress caused by pulling the material. The strength of structures of equal cross-sectional area loaded in tension is independent of shape of the cross-section. Materials loaded in tension are susceptible to stress concentrations such as material defects or abrupt changes in geometry. However, materials exhibiting ductile behaviour (many metals for example) can tolerate some defects while brittle materials (such as ceramics and some steels) can fail well below their ultimate material strength.

- Shear stress is the stress state caused by the combined energy of a pair of opposing forces acting along parallel lines of action through the material, in other words, the stress caused by faces of the material sliding relative to one another. An example is cutting paper with scissors[4] or stresses due to torsional loading.

Stress parameters for resistance

[edit]Material resistance can be expressed in several mechanical stress parameters. The term material strength is used when referring to mechanical stress parameters. These are physical quantities with dimension homogeneous to pressure and force per unit surface. The traditional measure unit for strength are therefore MPa in the International System of Units, and the psi between the United States customary units. Strength parameters include: yield strength, tensile strength, fatigue strength, crack resistance, and other parameters.[citation needed]

- Yield strength is the lowest stress that produces a permanent deformation in a material. In some materials, like aluminium alloys, the point of yielding is difficult to identify, thus it is usually defined as the stress required to cause 0.2% plastic strain. This is called a 0.2% proof stress.[5]

- Compressive strength is a limit state of compressive stress that leads to failure in a material in the manner of ductile failure (infinite theoretical yield) or brittle failure (rupture as the result of crack propagation, or sliding along a weak plane – see shear strength).

- Tensile strength or ultimate tensile strength is a limit state of tensile stress that leads to tensile failure in the manner of ductile failure (yield as the first stage of that failure, some hardening in the second stage and breakage after a possible "neck" formation) or brittle failure (sudden breaking in two or more pieces at a low-stress state). The tensile strength can be quoted as either true stress or engineering stress, but engineering stress is the most commonly used.

- Fatigue strength is a more complex measure of the strength of a material that considers several loading episodes in the service period of an object,[6] and is usually more difficult to assess than the static strength measures. Fatigue strength is quoted here as a simple range (). In the case of cyclic loading it can be appropriately expressed as an amplitude usually at zero mean stress, along with the number of cycles to failure under that condition of stress.

- Impact strength is the capability of the material to withstand a suddenly applied load and is expressed in terms of energy. Often measured with the Izod impact strength test or Charpy impact test, both of which measure the impact energy required to fracture a sample. Volume, modulus of elasticity, distribution of forces, and yield strength affect the impact strength of a material. In order for a material or object to have a high impact strength, the stresses must be distributed evenly throughout the object. It also must have a large volume with a low modulus of elasticity and a high material yield strength.[7]

Strain parameters for resistance

[edit]- Deformation of the material is the change in geometry created when stress is applied (as a result of applied forces, gravitational fields, accelerations, thermal expansion, etc.). Deformation is expressed by the displacement field of the material.[8]

- Strain, or reduced deformation, is a mathematical term that expresses the trend of the deformation change among the material field. Strain is the deformation per unit length.[9] In the case of uniaxial loading the displacement of a specimen (for example, a bar element) lead to a calculation of strain expressed as the quotient of the displacement and the original length of the specimen. For 3D displacement fields it is expressed as derivatives of displacement functions in terms of a second-order tensor (with 6 independent elements).

- Deflection is a term to describe the magnitude to which a structural element is displaced when subject to an applied load.[10]

Stress–strain relations

[edit]

- Elasticity is the ability of a material to return to its previous shape after stress is released. In many materials, the relation between applied stress is directly proportional to the resulting strain (up to a certain limit), and a graph representing those two quantities is a straight line.

The slope of this line is known as Young's modulus, or the "modulus of elasticity". The modulus of elasticity can be used to determine the stress–strain relationship in the linear-elastic portion of the stress–strain curve. The linear-elastic region is either below the yield point, or if a yield point is not easily identified on the stress–strain plot it is defined to be between 0 and 0.2% strain, and is defined as the region of strain in which no yielding (permanent deformation) occurs.[11]

- Plasticity or plastic deformation is the opposite of elastic deformation and is defined as unrecoverable strain. Plastic deformation is retained after the release of the applied stress. Most materials in the linear-elastic category are usually capable of plastic deformation. Brittle materials, like ceramics, do not experience any plastic deformation and will fracture under relatively low strain, while ductile materials such as metallics, lead, or polymers will plastically deform much more before a fracture initiation.

Consider the difference between a carrot and chewed bubble gum. The carrot will stretch very little before breaking. The chewed bubble gum, on the other hand, will plastically deform enormously before finally breaking.

Design terms

[edit]Ultimate strength is an attribute related to a material, rather than just a specific specimen made of the material, and as such it is quoted as the force per unit of cross section area (N/m2). The ultimate strength is the maximum stress that a material can withstand before it breaks or weakens.[12] For example, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of AISI 1018 Steel is 440 MPa. In Imperial units, the unit of stress is given as lbf/in2 or pounds-force per square inch. This unit is often abbreviated as psi. One thousand psi is abbreviated ksi.

A factor of safety is a design criteria that an engineered component or structure must achieve. , where FS: the factor of safety, Rf The applied stress, and F: ultimate allowable stress (psi or MPa)[13]

Margin of Safety is the common method for design criteria. It is defined MS = Pu/P − 1.

For example, to achieve a factor of safety of 4, the allowable stress in an AISI 1018 steel component can be calculated to be = 440/4 = 110 MPa, or = 110×106 N/m2. Such allowable stresses are also known as "design stresses" or "working stresses".

Design stresses that have been determined from the ultimate or yield point values of the materials give safe and reliable results only for the case of static loading. Many machine parts fail when subjected to a non-steady and continuously varying loads even though the developed stresses are below the yield point. Such failures are called fatigue failure. The failure is by a fracture that appears to be brittle with little or no visible evidence of yielding. However, when the stress is kept below "fatigue stress" or "endurance limit stress", the part will endure indefinitely. A purely reversing or cyclic stress is one that alternates between equal positive and negative peak stresses during each cycle of operation. In a purely cyclic stress, the average stress is zero. When a part is subjected to a cyclic stress, also known as stress range (Sr), it has been observed that the failure of the part occurs after a number of stress reversals (N) even if the magnitude of the stress range is below the material's yield strength. Generally, higher the range stress, the fewer the number of reversals needed for failure.

Failure theories

[edit]There are four failure theories: maximum shear stress theory, maximum normal stress theory, maximum strain energy theory, and maximum distortion energy theory (von Mises criterion of failure). Out of these four theories of failure, the maximum normal stress theory is only applicable for brittle materials, and the remaining three theories are applicable for ductile materials. Of the latter three, the distortion energy theory provides the most accurate results in a majority of the stress conditions. The strain energy theory needs the value of Poisson's ratio of the part material, which is often not readily available. The maximum shear stress theory is conservative. For simple unidirectional normal stresses all theories are equivalent, which means all theories will give the same result.

- Maximum shear stress theory postulates that failure will occur if the magnitude of the maximum shear stress in the part exceeds the shear strength of the material determined from uniaxial testing.

- Maximum normal stress theory postulates that failure will occur if the maximum normal stress in the part exceeds the ultimate tensile stress of the material as determined from uniaxial testing. This theory deals with brittle materials only. The maximum tensile stress should be less than or equal to ultimate tensile stress divided by factor of safety. The magnitude of the maximum compressive stress should be less than ultimate compressive stress divided by factor of safety.

- Maximum strain energy theory postulates that failure will occur when the strain energy per unit volume due to the applied stresses in a part equals the strain energy per unit volume at the yield point in uniaxial testing.

- Maximum distortion energy theory, also known as maximum distortion energy theory of failure or von Mises–Hencky theory. This theory postulates that failure will occur when the distortion energy per unit volume due to the applied stresses in a part equals the distortion energy per unit volume at the yield point in uniaxial testing. The total elastic energy due to strain can be divided into two parts: one part causes change in volume, and the other part causes a change in shape. Distortion energy is the amount of energy that is needed to change the shape.

- Fracture mechanics was established by Alan Arnold Griffith and George Rankine Irwin. This important theory is also known as numeric conversion of toughness of material in the case of crack existence.

A material's strength depends on its microstructure. The engineering processes to which a material is subjected can alter its microstructure. Strengthening mechanisms that alter the strength of a material include work hardening, solid solution strengthening, precipitation hardening, and grain boundary strengthening.

Strengthening mechanisms are accompanied by the caveat that some other mechanical properties of the material may degenerate in an attempt to make a material stronger. For example, in grain boundary strengthening, although yield strength is maximized with decreasing grain size, ultimately, very small grain sizes make the material brittle. In general, the yield strength of a material is an adequate indicator of the material's mechanical strength. Considered in tandem with the fact that the yield strength is the parameter that predicts plastic deformation in the material, one can make informed decisions on how to increase the strength of a material depending on its microstructural properties and the desired end effect. Strength is expressed in terms of the limiting values of the compressive stress, tensile stress, and shear stresses that would cause failure. The effects of dynamic loading are probably the most important practical consideration of the theory of elasticity, especially the problem of fatigue. Repeated loading often initiates cracks, which grow until failure occurs at the corresponding residual strength of the structure. Cracks always start at a stress concentrations especially changes in cross-section of the product or defects in manufacturing, near holes and corners at nominal stress levels far lower than those quoted for the strength of the material.

See also

[edit]- Creep (deformation) – Tendency of a solid material to move slowly or deform permanently under mechanical stress

- Deformation mechanism map – Microscopic processes responsible for changes in a material's structure, shape and volume

- Dynamics – Study of forces and their effect on motion

- Forensic engineering – Investigation of failures associated with legal intervention

- Fracture toughness – Stress intensity factor at which a crack's propagation increases drastically

- List of materials properties § Mechanical properties

- Materials science – Research of materials

- Material selection – Step in the process of designing physical objects

- Molecular diffusion – Thermal motion of liquid or gas particles at temperatures above absolute zero

- Soft-body dynamics – Computer graphics simulation of deformable objects

- Specific strength – Ratio of strength to mass for a material

- Statics – Branch of mechanics concerned with balance of forces in nonmoving systems

- Universal testing machine – Type of equipment for determining tensile or compressive strength of a material

References

[edit]- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer, Ferdinand Pierre; Johnston, Elwood Russell; Dewolf, John T (2009). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). p. 52. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 693–696. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ R. C. Hibbeler (2009). Structural Analysis (7 ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 305. ISBN 978-0-13-602060-8.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 53–56. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5thv ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

- ^ Beer & Johnston (2006). Mechanics of Materials (5th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-07-352938-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Fa-Hwa Cheng, Initials. (1997). Strength of material. Ohio: McGraw-Hill

- Mechanics of Materials, E.J. Hearn

- Alfirević, Ivo. Strength of Materials I. Tehnička knjiga, 1995. ISBN 953-172-010-X.

- Alfirević, Ivo. Strength of Materials II. Tehnička knjiga, 1999. ISBN 953-6168-85-5.

- Ashby, M.F. Materials Selection in Design. Pergamon, 1992.

- Beer, F.P., E.R. Johnston, et al. Mechanics of Materials, 3rd edition. McGraw-Hill, 2001. ISBN 0-07-248673-2

- Cottrell, A.H. Mechanical Properties of Matter. Wiley, New York, 1964.

- Den Hartog, Jacob P. Strength of Materials. Dover Publications, Inc., 1961, ISBN 0-486-60755-0.

- Drucker, D.C. Introduction to Mechanics of Deformable Solids. McGraw-Hill, 1967.

- Gordon, J.E. The New Science of Strong Materials. Princeton, 1984.

- Groover, Mikell P. Fundamentals of Modern Manufacturing, 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002. ISBN 0-471-40051-3.

- Hashemi, Javad and William F. Smith. Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering, 4th edition. McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 0-07-125690-3.

- Hibbeler, R.C. Statics and Mechanics of Materials, SI Edition. Prentice-Hall, 2004. ISBN 0-13-129011-8.

- Lebedev, Leonid P. and Michael J. Cloud. Approximating Perfection: A Mathematician's Journey into the World of Mechanics. Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-691-11726-8.

- Chapter 10 – Strength of Elastomers, A.N. Gent, W.V. Mars, In: James E. Mark, Burak Erman and Mike Roland, Editor(s), The Science and Technology of Rubber (Fourth Edition), Academic Press, Boston, 2013, Pages 473–516, ISBN 9780123945846, 10.1016/B978-0-12-394584-6.00010-8

- Mott, Robert L. Applied Strength of Materials, 4th edition. Prentice-Hall, 2002. ISBN 0-13-088578-9.

- Popov, Egor P. Engineering Mechanics of Solids. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N. J., 1990. ISBN 0-13-279258-3.

- Ramamrutham, S. Strength of Materials.

- Shames, I.H. and F.A. Cozzarelli. Elastic and inelastic stress analysis. Prentice-Hall, 1991. ISBN 1-56032-686-7.

- Timoshenko S. Strength of Materials, 3rd edition. Krieger Publishing Company, 1976, ISBN 0-88275-420-3.

- Timoshenko, S.P. and D.H. Young. Elements of Strength of Materials, 5th edition. (MKS System)

- Davidge, R.W., Mechanical Behavior of Ceramics, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, (1979)

- Lawn, B.R., Fracture of Brittle Solids, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, 2nd Edn. (1993)

- Green, D., An Introduction to the Mechanical Properties of Ceramics, Cambridge Solid State Science Series, Eds. Clarke, D.R., Suresh, S., Ward, I.M.Babu Tom.K (1998)

External links

[edit]Strength of materials

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Scope

Strength of materials, also known as mechanics of materials, is a branch of solid mechanics that studies the behavior of solid objects subjected to various loads, focusing on the relationship between external forces applied to deformable bodies and the resulting internal forces and deformations.[3] This field examines how materials resist deformation and failure under mechanical loading, providing the foundation for predicting the performance of engineering components.[1] The scope of strength of materials encompasses the analysis of stresses, strains, and deformations in practical engineering structures such as beams, shafts, and pressure vessels, aiming to ensure they can support anticipated loads without excessive distortion or rupture.[1] Unlike fracture mechanics, which specifically addresses crack initiation and propagation in materials with pre-existing flaws, strength of materials deals with the overall load-bearing capacity of intact structures.[10] It also differs from the broader continuum mechanics, serving as an applied subset that translates theoretical continuum principles into design methodologies for discrete components.[11] Core concepts like stress (internal force per unit area) and strain (relative deformation) form the basis for these analyses, though detailed formulations are explored elsewhere.[1] In civil, mechanical, and aerospace engineering, strength of materials plays a critical role in verifying structural integrity under operational conditions, enabling the design of safe and efficient systems such as bridges, aircraft frames, and machinery parts.[12] This discipline ensures that materials can endure service loads while minimizing risks of failure, thereby enhancing reliability and longevity across diverse applications.[12] A key assumption in strength of materials is that the analyzed materials are homogeneous (uniform properties throughout), isotropic (properties independent of direction), and exhibit linear elastic behavior unless otherwise specified, simplifying calculations while approximating real-world conditions.[13][14]Historical Development

The development of the strength of materials began with empirical practices in ancient civilizations. Around 3000 BCE, the ancient Egyptians utilized practical rules derived from observation to construct stable structures like the pyramids, relying on the compressive strength of stone blocks and the geometry of inclined planes to distribute loads effectively.[8] Similarly, the Greeks applied intuitive knowledge of material limits in building arches and temples, such as the Parthenon, where they balanced tensile and compressive forces in stone and timber without formal analysis.[8] These early approaches marked the inception of structural design based on trial-and-error experience rather than theoretical principles. During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci advanced these ideas through qualitative studies in the 15th century. In his manuscripts, da Vinci sketched elastic deformations of wooden beams under varying loads, illustrating sagging and force interactions, and hypothesized that plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis post-deformation—a concept central to later beam theory.[15] The 17th and 18th centuries saw foundational theoretical progress; Galileo Galilei, in his 1638 work Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences, introduced concepts of beam bending resistance, modeling a cantilever beam's strength as proportional to the square of its depth and using parabolic stress distribution assumptions.[16] Leonhard Euler extended this in the mid-18th century with his buckling theory for slender columns, deriving the critical load formula in 1757 that predicts instability under axial compression based on material stiffness and geometry.[17] The 19th century formalized continuum mechanics, enabling rigorous analysis of material strength. Claude-Louis Navier and Augustin-Louis Cauchy laid the groundwork by developing the mathematical framework for continuous media; Navier incorporated viscosity into fluid equations in 1822, while Cauchy introduced the stress tensor in 1823 and 1827, providing tools to describe internal forces in deformable solids.[18] In 1855, Adhémar Jean Claude Barré de Saint-Venant established his principle, stating that the stress distribution in a body distant from the loaded region is independent of the exact loading details, as long as the resultant force and moment are equivalent, which simplifies boundary condition analyses. The 20th century shifted toward plasticity and computational methods. Richard von Mises proposed his yield criterion in 1913, defining yielding in ductile materials when distortional strain energy reaches a critical value, offering a multiaxial extension of uniaxial tensile tests for predicting plastic onset.[19] The finite element method emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, pioneered by Ray Clough and others at the University of California, Berkeley, discretizing complex structures into elements to solve stress distributions numerically, revolutionizing aircraft and civil engineering design.[20] Post-1980s integration with computational tools, including finite element software and high-performance computing, enabled simulations of nonlinear behaviors and large-scale structures, as seen in NASA applications for dynamics and mechanics.[21] Since the 2000s, the field has incorporated nanomaterials and composites, addressing anisotropic behaviors where properties vary by direction, such as in carbon nanotube-reinforced polymers that exhibit direction-dependent stiffness and failure modes under multiaxial loads.[22]Basic Concepts

Types of Loadings

Loadings in the strength of materials refer to the external forces or conditions applied to a body that induce internal stresses, which are essential for analyzing material behavior under service conditions. These loadings are broadly classified into static and dynamic categories based on their variation over time. Static loadings are those that are constant or change very slowly, allowing the material to reach equilibrium without significant inertial effects; examples include dead loads from the permanent weight of structures like buildings or bridges.[23] In contrast, dynamic loadings vary rapidly with time, often involving acceleration or deceleration that introduces inertial forces; common instances are impact loads from sudden collisions or cyclic loads leading to fatigue in rotating machinery.[24] Axial loadings act along the longitudinal axis of a structural member, either pulling it apart or pushing it together. Tension, a type of axial loading, elongates the material by applying forces that tend to increase its length, as seen in suspension cables or tie rods supporting tensile forces.[25] Compression, the opposing axial loading, shortens the material through forces that reduce its length, typical in columns or struts bearing downward weights in frameworks.[25] Torsional loading involves twisting forces applied about the axis of a member, generating shear stresses that can cause angular deformation. This type is prevalent in drive shafts transmitting rotational power in engines or turbines, where torque from motors induces circumferential shear.[26] Bending, or flexural, loading occurs when transverse forces or moments cause a beam or plate to curve, resulting in varying stresses across the cross-section. Such loadings are common in beams supporting distributed weights, like floor joists in buildings, where the moment from applied loads leads to concave or convex deformation.[27] Shear loading applies forces parallel to the cross-sectional area of a member, promoting sliding between layers without significant normal deformation. This is evident in riveted joints or bolts, where transverse forces attempt to shear the connection apart.[27] Combined loadings arise when multiple types act simultaneously on a component, requiring superposition principles to assess the overall effect. For instance, machine parts like crankshafts experience axial tension, bending from reciprocating forces, and torsion from rotational torque concurrently.[28] Environmental factors introduce additional loadings beyond mechanical forces, such as thermal loading from temperature gradients causing expansion or contraction. In pipelines or aircraft components, uneven heating leads to differential thermal expansion that superimposes on mechanical stresses.[29] Hydrostatic pressure loading, a uniform compressive force from surrounding fluids, acts equally in all directions, as in submersible vehicles or underwater pipelines where external fluid pressure exerts omnidirectional compressive forces on the structure.[30] These loading types collectively determine the stress states within materials, forming the basis for subsequent analysis.Stress Fundamentals

Stress is defined as the internal resistance of a material to external loads, quantified as the force per unit area acting on a plane within the material to resist deformation.[31] It arises from the distribution of internal forces that balance applied loads, ensuring equilibrium in the body.[32] The SI unit of stress is the pascal (Pa), equivalent to one newton per square meter (N/m²), while the customary unit in engineering is pounds per square inch (psi).[32] Normal stress, denoted by σ, occurs when forces act perpendicular to a cross-sectional area, either pulling the material apart (tensile stress, conventionally positive) or pushing it together (compressive stress, conventionally negative).[33] In uniaxial loading, the average normal stress is calculated as σ = F / A, where F is the axial force and A is the cross-sectional area perpendicular to the force.[34] Shear stress, denoted by τ, results from forces parallel to the cross-sectional area, promoting sliding along planes within the material; for average shear in simple cases, τ = F / A, with F as the transverse force.[35] Principal stresses represent the maximum and minimum normal stresses at a point, occurring on planes where shear stress is zero, and can be visualized qualitatively using Mohr's circle, a graphical tool that transforms stress states by plotting normal and shear stress components.[36] Stress distribution varies by loading: it is uniform across the cross-section in simple axial cases, assuming the load passes through the centroid, but becomes non-uniform in bending (linear variation from tension to compression across the neutral axis) or torsion (linear with radial distance from the center).[24][37] Allowable stress is the maximum stress a material can safely sustain, derived from its yield or ultimate strength divided by a factor of safety to account for uncertainties, and adjusted for environmental factors such as temperature, which can reduce material strength.[38][39]Strain Fundamentals

Strain is a measure of the deformation experienced by a material under applied loads, quantifying the relative change in dimensions such as length, angle, or volume. It is a dimensionless quantity that describes how a body distorts geometrically in response to stress, independent of the material's size. The engineering strain, commonly used for small deformations, is defined as the change in length ΔL divided by the original length L, expressed as ε = ΔL / L. For larger deformations, true strain accounts for the instantaneous length, defined as ε_true = ln(L / L_0), providing a more accurate representation in processes like metal forming where significant elongation occurs.[30][40][41] Normal strain refers to the linear deformation along the direction of an applied normal stress, resulting in either extension (tensile strain, positive ε) or contraction (compressive strain, negative ε). This is calculated using the engineering strain formula ε = ΔL / L for a line element originally of length L that changes by ΔL after loading. In tensile loading, the material elongates longitudinally, while compressive loading shortens it, with the strain value indicating the fractional change. Shear strain, in contrast, measures angular distortion in a material body, defined as γ = tan(θ), where θ is the change in the right angle between two originally perpendicular line elements due to shear stress. For small angles typical in engineering applications, γ ≈ θ (in radians), approximating the tangent without significant error.[41][34][35][42] Volumetric strain describes the relative change in a material's volume under loading, particularly in hydrostatic conditions where equal normal stresses act in all directions, given by δV / V, where δV is the change in volume and V is the original volume. This strain is influenced by the Poisson effect, in which lateral contraction or expansion accompanies longitudinal deformation, leading to overall volume change; for instance, in uniaxial tension, the volume may slightly increase or decrease depending on the material's Poisson's ratio. Strain compatibility ensures that deformations in a continuous body satisfy geometric constraints, meaning the strain field must be such that the deformed shape remains connected without gaps or overlaps—for example, in beam bending, the assumption that plane cross-sections remain plane after deformation enforces compatibility along the beam's length.[43][44][45] Strain is measured using various techniques, with strain gauges being a primary method; these electrical resistance devices, bonded to the surface, change resistance proportionally to surface strain, enabling precise quantification down to microstrains. Extensometers, mechanical or optical devices clipped to the specimen, directly measure elongation over a gage length by tracking relative displacement of reference points. Historically, early mechanical indicators, such as the Martens extensometer developed in the late 19th century, used lever systems and mirrors to amplify and optically read small deformations, paving the way for modern instrumentation before the advent of electrical gauges in the early 20th century.[46][47][48]Material Response

Stress-Strain Relationships

The stress-strain relationship in materials under loading is fundamentally described by constitutive equations that link applied stresses to resulting deformations, with linear elasticity forming the cornerstone for many engineering analyses. In the simplest case of uniaxial tension, Hooke's law states that the normal stress is directly proportional to the normal strain , expressed as , where is the Young's modulus representing the material's stiffness.[49] This relation holds within the elastic limit, where deformations are reversible upon unloading.[50] For three-dimensional stress states, Hooke's law generalizes to account for interactions between principal directions, incorporating Poisson's ratio , which quantifies the lateral contraction accompanying axial extension. The strain in the -direction, for instance, is given by , with analogous expressions for and . Shear strains follow a separate linear relation , where is the shear modulus, related to and by .[51] In multiaxial loading, the full stress-strain relations for isotropic materials—those exhibiting uniform properties in all directions—are captured using tensor notation and a compliance matrix , where the strain tensor . For isotropic cases, this 6×6 matrix simplifies to two independent constants, and , enabling prediction of deformations under combined normal and shear stresses without directional dependence./03%3A_General_Concepts_of_Stress_and_Strain/3.04%3A_Constitutive_Relations) These relations assume infinitesimal strains, typically below 0.1–0.2% for metals, ensuring geometric linearity and full elastic recovery, in contrast to nonlinear regimes where higher strains lead to coupled, path-dependent responses.[52] Temperature variations introduce additional strains independent of mechanical loading, given by the thermal strain , where is the coefficient of thermal expansion and is the temperature change; this term superimposes on mechanical strains in the total deformation.[53] In polymers, deviations from ideal linear elasticity arise due to viscoelasticity, manifesting as time-dependent creep or relaxation under sustained loads, where strain continues to evolve even at constant stress.[54]Elastic and Plastic Behavior

In materials subjected to loading, elastic behavior occurs when deformation is reversible, allowing the material to return to its original shape upon removal of the stress. This region is characterized by a linear relationship between stress and strain up to the proportional limit, beyond which the response may remain elastic but becomes nonlinear until the elastic limit is reached.[55][56] Beyond the elastic limit, plastic behavior dominates, resulting in permanent deformation as atomic bonds slip and dislocations move within the crystal lattice, preventing full recovery even after stress removal. The onset of plasticity is marked by the yield point, where significant irreversible straining begins; for many ductile materials lacking a distinct yield drop, this is conventionally defined as the 0.2% offset yield strength, determined by drawing a line parallel to the elastic modulus slope offset by 0.002 strain and finding its intersection with the stress-strain curve.[55][56] The typical stress-strain curve for a ductile material illustrates these behaviors in distinct stages: an initial elastic phase with linear strain up to the proportional limit, followed by yielding—often featuring a plateau in mild steels where strain increases with little stress rise due to rapid dislocation multiplication—a strain hardening phase where stress rises again as dislocations tangle and impede further motion, necking where localized deformation reduces cross-section leading to instability, and finally fracture.[40] In the strain hardening stage, known as work hardening, the material's flow stress increases with accumulated plastic strain because interactions between dislocations on intersecting slip planes create barriers that require higher stresses for continued deformation.[57] Ductility and brittleness further distinguish material responses in the plastic regime, with ductility reflecting the ability to undergo substantial permanent deformation before fracture, quantified by elongation at break—the percentage increase in length from original to fractured state—while brittleness indicates minimal plastic flow leading to sudden failure. Materials exhibiting elongation at break greater than 5%, such as steels, are generally ductile, enabling energy absorption through deformation, whereas those below 5%, like glass, behave brittly with little warning.[56] A notable phenomenon in plastic deformation is the Bauschinger effect, where prior straining in one direction lowers the yield strength upon reversal of loading due to changes in internal long-range stresses from back-stresses associated with dislocation pile-ups.[58] This effect highlights the anisotropic nature of hardening in polycrystalline materials and influences fatigue and cyclic loading performance.Key Material Properties

The key material properties in strength of materials analysis quantify how substances respond to mechanical loads, enabling engineers to predict deformation, failure, and durability under various conditions. These properties, derived from experimental testing, vary by material class and are essential for selecting appropriate substances in structural applications. Among the most fundamental are measures of elastic stiffness, such as Young's modulus, which indicates a material's resistance to axial deformation. Young's modulus (E), also known as the modulus of elasticity, represents the stiffness of a material in the linear elastic regime and is defined as the ratio of axial stress to axial strain. For structural steel, E is approximately 200 GPa, providing high rigidity suitable for load-bearing components. In contrast, aluminum alloys exhibit a lower value of about 70 GPa, reflecting greater deformability but reduced weight, which is advantageous in aerospace designs. The shear modulus (G), or modulus of rigidity, measures resistance to shear deformation and is related to Young's modulus by the formula , where is Poisson's ratio, assuming isotropic behavior. For steel, G typically reaches 80 GPa, enabling effective performance in torsion-loaded elements like shafts. Poisson's ratio () quantifies the negative ratio of transverse to axial strain during uniaxial loading, capturing lateral contraction effects; it averages 0.3 for most metals, influencing volumetric changes under stress. Ultimate tensile strength (UTS) denotes the maximum engineering stress a material sustains before fracturing in tension, marking the peak of the stress-strain curve. Mild steel, for instance, achieves a UTS of around 400 MPa, balancing strength and ductility for construction uses. Fatigue strength, particularly the endurance limit for high-cycle loading, represents the stress amplitude below which a material withstands infinite cycles without failure; for steels, this is roughly 50% of UTS, critical for components like aircraft wings subjected to repeated vibrations. Material properties are influenced by external and internal factors, altering performance in real-world scenarios. Elevated temperatures generally decrease Young's modulus, as thermal expansion softens atomic bonds in metals like steel. Higher strain rates, such as those in impact events, increase yield strength by limiting dislocation motion, enhancing toughness in dynamic applications. Microstructural features, including grain size, also play a key role; finer grains elevate strength per the Hall-Petch relation, where yield stress rises inversely with the square root of grain diameter, due to increased grain boundary impediments to dislocation glide.| Material | Young's Modulus (E, GPa) | Shear Modulus (G, GPa) | Poisson's Ratio () | Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel (mild) | 200 | 80 | 0.3 | 400 |

| Aluminum alloy | 70 | 26 | 0.33 | 300 |

| Concrete | 30 | 12.5 | 0.2 | 3 (tensile) |

| Polymer (PLA) | 3 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 50 |