Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

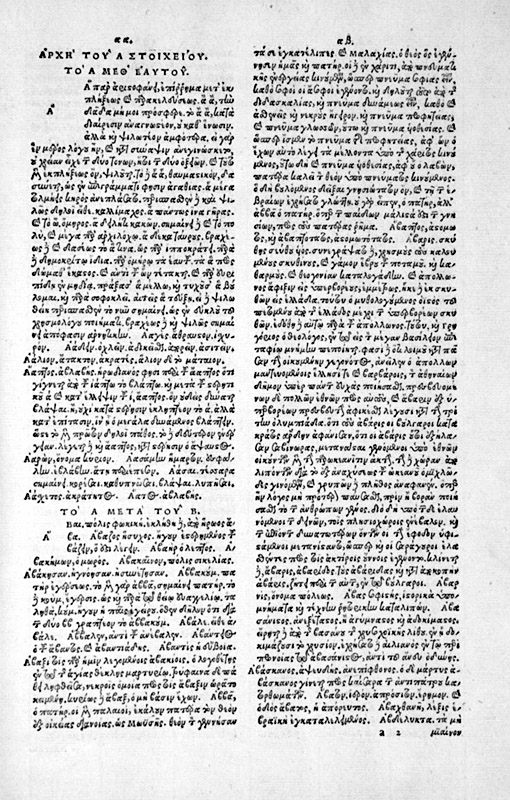

The Suda or Souda (/ˈsuːdə/; Medieval Greek: Σοῦδα Soûda [ˈsuða]; Latin: Suidae Lexicon)[1] is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas (Σουίδας). It is an encyclopedic lexicon, written in Greek, with 30,000 entries, many drawing from ancient sources that have since been lost, and often derived from medieval Christian compilers.

Title

[edit]The exact spelling of the title is disputed.[2] The transmitted title (paradosis) is "Suida", which is also attested in Eustathius' commentary on Homer's epic poems; several conjectures have been made, both defending it and trying to correct it in "Suda".[3]

- Paul Maas advocated for the Σοῦδα spelling, connecting it to the Latin verb sūdā, the second-person singular imperative of sūdāre, "to sweat".[4]

- Franz Dölger also defended Σοῦδα, tracing its origins back to Byzantine military lexicon (σοῦδα, "ditch, trench", then "fortress").[5][6]

- Henri Grégoire, starting from a critique to Dölger's interpretation, defended a proposal advanced by one of his pupils, and explained the word Σοῦδα as the acrostic of Συναγογὴ ὀνομάτων ὑπὸ διαφόρων ἀνδρῶν σοφῶν, "Collection of names (words) by different learned men", or alternatively Συναγογὴ ὀνομαστικῆς ὕλης δι’ ἀλφαβήτου, "Collection of lexicographical material in alphabetical order".[7][8][9][10] This suggestion was also supported by French Hellenist and Byzantinist Alphonse Dain.[11]

- Silvio Giuseppe Mercati wrote on the matter twice: firstly in an article appeared in the academic journal Byzantion,[12] and later in an expanded version of the same.[13] He suggested a link with the Neo-Latin substantive guida ("guide"), transliterated in Greek as γουίδα and later miswritten as σουίδα. This interpretation was strongly criticized by Dölger, who also refused to publish Mercati's first article in the Byzantinische Zeitschrift; on the other hand, Giuseppe Schirò supported it.[14][15]

- Bertrand Hemmerdinger interpreted Σουΐδας as a Doric genitive.[16]

Other suggestions include Jan Sajdak's theory that σοῦδα / σουίδα may derive from Sanskrit सुविद्या suvidyā (which he translated into Latin: perfecta cumulataque scientia, "collected and systemized knowledge");[17][18] Giuseppe Scarpat's link to an unidentified Judas, the supposed author of the Lexicon;[19] and Hans Gerstinger's explanation which points at Russian сюда sjudá "here", as the answer to the question "τί ποῦ κεῖται;" "what and where is it?".[20] The most recent explanation[which?] as of 2024 has been advanced by Claudia Nuovo, who defended Σοῦδα on palaeographical, philological and historical grounds[how?].[3]

Content and sources

[edit]pecus est Suidas, sed pecus aurei velleris

[Suidas is cattle, but cattle with a golden fleece]

— Lipsius

The Suda is somewhere between a grammatical dictionary and an encyclopedia in the modern sense. It explains the source, derivation, and meaning of words according to the philology of its period, using such earlier authorities as Harpocration and Helladios.[21][22] It is a rich source of ancient and Byzantine history and life, although not every article is of equal quality, and it is an "uncritical" compilation.[21]

Much of the work is probably interpolated,[21] and passages that refer to Michael Psellos (c. 1017–1078) are deemed interpolations which were added in later copies.[21]

Biographical notices

[edit]This lexicon contains numerous biographical notices on political, ecclesiastical, and literary figures of the Byzantine Empire to the tenth century, those biographical entries being condensations from the works of Hesychius of Miletus, as the author himself avers. Other sources were the encyclopedia of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (reigned 912–959) for the figures in ancient history, excerpts of John of Antioch (seventh century) for Roman history, the chronicle of Hamartolus (Georgios Monachos, 9th century) for the Byzantine age[22][21][24], the biographies of Diogenes Laërtius, and the works of Athenaeus and Philostratus. Other principal sources include a lexicon by "Eudemus," perhaps derived from the work On Rhetorical Language by Eudemus of Argos.[25]

Lost scholia

[edit]The lexicon copiously draws from scholia to the classics (Homer, Aristophanes, Thucydides, Sophocles, etc.), and for later writers, Polybius, Josephus, the Chronicon Paschale, George Syncellus, George Hamartolus, and so on.[21][22] The Suda quotes or paraphrases these sources at length. Since many of the originals are lost, the Suda serves as an invaluable repository of literary history, and this preservation of the "literary history" is more vital than the lexicographical compilation itself, by some estimation.[22]

Organization

[edit]

The lexicon is arranged alphabetically with some slight deviations from common vowel order and place in the Greek alphabet[21] (including at each case the homophonous digraphs, e.g. αι, ει, οι, that had been previously, earlier in the history of Greek, distinct diphthongs or vowels) according to a system (formerly common in many languages) called antistoichia (ἀντιστοιχία); namely the letters follow phonetically in order of sound according the pronunciation of the tenth century, which was similar to that of Modern Greek. The order is:

α, β, γ, δ, αι, ε, ζ, ει, η, ι, θ, κ, λ, μ, ν, ξ, ο, ω, π, ρ, σ, τ, οι, υ, φ, χ, ψ[26]

In addition, double letters are treated as single for the purposes of collation (as gemination had ceased to be distinctive). The system is not difficult to learn and remember, but some editors—for example, Immanuel Bekker—rearranged the Suda alphabetically.

Background

[edit]Little is known about the compiler of the Suda. He probably lived in the second half of the 10th century, because the death of emperor John I Tzimiskes and his succession by Basil II and Constantine VIII are mentioned in the entry under "Adam", which has a brief chronology of the world appended.[21] At any rate, the work must have appeared by the 12th century, since it is frequently quoted from and alluded to by Eustathius who lived from about 1115 to about 1195–1196.[21] It has also been stated that the work was a collective work, thus not having had a single author, and that the name which it is known under does not refer to a specific person.[27]

The work deals with biblical as well as pagan subjects, from which it is inferred that the writer was a Christian.[21] In any case, it lacks definite guidelines besides some minor interest in religious matters.[27]

The standard printed edition was compiled by Danish classical scholar Ada Adler in the first half of the twentieth century. A modern collaborative English translation, the Suda On Line, was completed on 21 July 2014.[28]

The Suda has a near-contemporaneous Islamic parallel, the Kitab al-Fihrist of Ibn al-Nadim. Compare also the Latin Speculum Maius, authored in the 13th century by Vincent of Beauvais.

Editions

[edit]- Küster, Ludolf, ed. (1705). Suidae Lexicon, Graece & Latine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.: vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3.

- Gaisford, Thomas, ed. (1834). Suidae Lexicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press.: vol. 1 (A–Θ), vol. 2 (Κ–Ψ), vol. 3 (Indices).

- Bekker, Immanuel, ed. (1854). Suidae Lexicon. Berlin: G. Reimer.

- Adler, Ada, ed. (1928–38). Suidae Lexicon. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. Reprinted 1967–71, Stuttgart.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gaisford Thomas, ed., (1834), Suidae Lexicon, 3 vols.

- ^ It is worth noticing that Adler's edition maintains the spelling Suida/Σουΐδα (as Gaisford's and Bekker's editions did), in continuity with the manuscripts, but modern scholarship prefers Suda/Σούδα.

- ^ a b Nuovo, Claudia (2022). "Un'ultima teichotaphromachia per il lessico Suda". Jahrbuch der österreichischen Byzantinistik. 72: 421–426.

- ^ Maas, Paul (1932). "Der Titel des "Suidas"". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 32 (1): 1. doi:10.1515/byzs.1932.32.1.1. S2CID 191333687 – via De Gruyter.

- ^ Dölger, Franz (1936). Der Titel der sogenannten Suidaslexicons. Sitzungsberichte der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Abteilung. Jahrgang 1936. Heft 6. München: Bayerische Akademie des Wissenschaften.

- ^ Dölger, Franz (1938). "Zur σοῦδα – Frage". Byzantinische Zeitschrift. 38 (1): 36–57. doi:10.1515/byzs.1938.38.1.36. S2CID 191479647.

- ^ Grégoire, Henri (1937). "Suidas et son mystère". Les études classiques. 6: 346–355.

- ^ Grégoire, Henri (1937). "Étymologies byzantino-latines". Byzantion. 12: 293–300, 658–666.

- ^ Grégoire, Henri (1938). "La teichotaphromachia". Byzantion. 13: 389–391.

- ^ Grégoire, Henri (1944–1945). "La fin d'une controverse: koptō taphron, taphrokopō". Byzantion. 17: 330–331.

- ^ Dain, Alphonse (1937). "Suda dans les traités militaires". Annuaire de l'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientales et Slaves. 5: 233–241.

- ^ Mercati, Silvio Giuseppe (1957). "Intorno al titolo dei lessici di Suida-Suda e di Papia". Byzantion. 25/26/27 (1): 173–93.

- ^ Mercati, Silvio Giuseppe (1960). "Intorno al titolo dei lessici di Suida-Suda e di Papia". Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Memorie, Classe di Scienze Morali, Storiche e Filologiche. 8 (10): 3–50.

- ^ Schirò, Giuseppe (1958). "Da Suida-Suda a Guida". Archivio Storico per la Calabria e la Lucania. 27: 171–176.

- ^ Schirò, Giuseppe (1962). "Si torna a Suida (= Guida)". Rivista di cultura classica e medioevale. 4: 240–241.

- ^ Hemmerdinger, Bertrand (1998). "Suidas, et non la Souda". Bollettino dei Classici. 3rd Series. 19: 31–32.

- ^ Sajdak, Jan (1933). "Literatura Bizantyńska". In Lam, S.; Brückner, A. (eds.). Wielka literatura powszechna Trzaski, Everta i Michalskiego. Vol. 4. Literatury słowiańskie, literatura bizantyjska i nowogrecka. Warszawa. p. 723.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sajdak, Jan (1934). "Liber Suda". Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk. Prace Komisji Filologicznej. 7: 249–272.

- ^ Scarpat, Giuseppe (1960–1961). "Una nuova ipotesi sull'autore del lessico detto di Suida". Atti del Sodalizio Glottologico Milanese. 14: 3–11.

- ^ Gerstringer, Hans (1961). "Review of: S. G. Mercati, Intorno al titolo dei lessici di Suida-Suda e di Papia, Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Memorie, Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche VIII, 10 (1960) 3–50". Gnomon. 50: 783–785.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chisholm (1911).

- ^ a b c d Herbermann (1913).

- ^ Krumbacher, Karl (1897), Byzantinische Literatur, p. 566, cited by Herbermann (1913)

- ^ Karl Krumbacher concluded the two main biographical sources were "Constantine VII for ancient history, Hamartolus (Georgios Monarchos) for the Byzantine age".[23]

- ^ Krumbacher, Karl, Geschichte der byzantinischen Litteratur, pp. 268f.

- ^ Gaisford, Thomas, ed., (1853) Suidae lexicon: Graecè et Latinè, Volume 1, Part 1, page XXXIX (in Greek and Latin)

- ^ a b Mazzucchi 2020.

- ^ "The History of the Suda On Line". Stoa. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

A translation of the last of the Suda's 31000+ entries was submitted to the database on July 21, 2014 and vetted the next day.

Also Mahoney, Anne (2009). "Tachypaedia Byzantina: The Suda On Line as Collaborative Encyclopedia". Digital Humanities Quarterly. 3 (1). Archived from the original on Dec 9, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Sūïdas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Dickey, Eleanor. Ancient Greek Scholarship: a guide to finding, reading, and understanding scholia, commentaries, lexica, and grammatical treatises, from their beginnings to the Byzantine period. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780195312935.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Suidas". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Suidas". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

[edit]- Index of the Suda on line

- Suda On Line. An on-line edition of the Greek (the Ada Adler edition) with full English translations and commentary.

- Suda lexicon at the Online Books Page

- Suda lexicon in Greek