Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Open data

View on Wikipedia

Open data are data that are openly accessible, exploitable, editable and shareable by anyone for any purpose. Open data are generally licensed under an open license.[1][2][3]

The goals of the open data movement are similar to those of other "open(-source)" movements such as open-source software, open-source hardware, open content, open specifications, open education, open educational resources, open government, open knowledge, open access, open science, and the open web. The growth of the open data movement is paralleled by a rise in intellectual property rights.[4] The philosophy behind open data has been long established (for example in the Mertonian tradition of science), but the term "open data" itself is recent, gaining popularity with the rise of the Internet and World Wide Web and, especially, with the launch of open-data government initiatives Data.gov, Data.gov.uk and Data.gov.in.

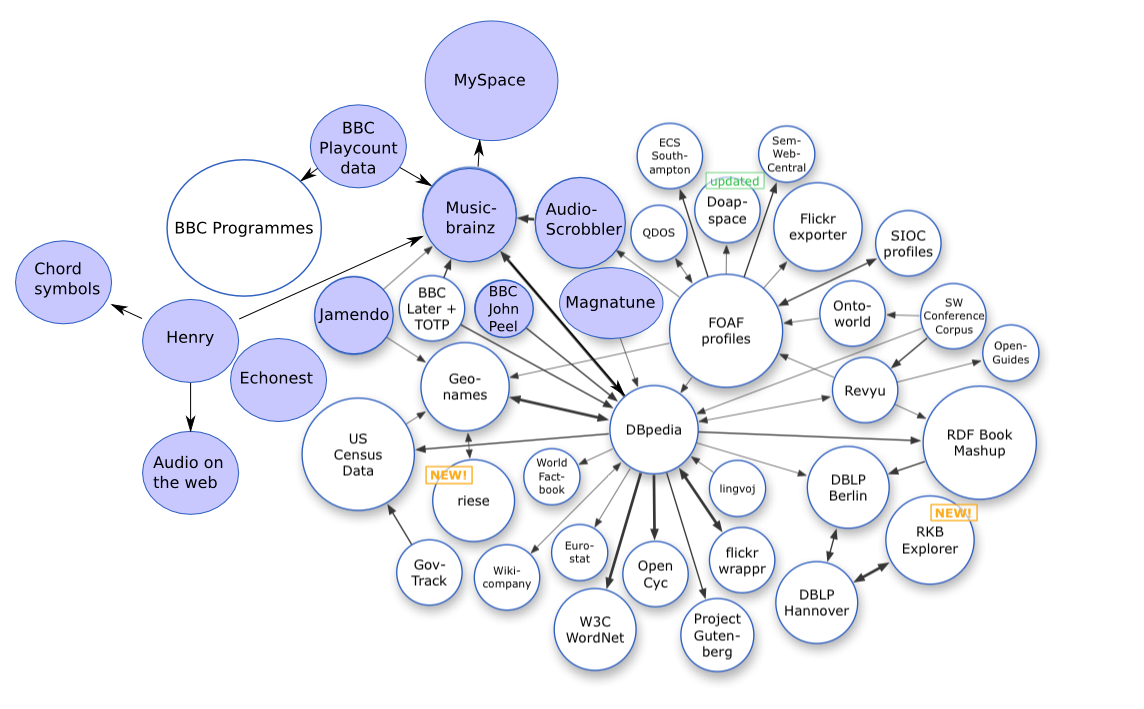

Open data can be linked data—referred to as linked open data.

One of the most important forms of open data is open government data (OGD), which is a form of open data created by ruling government institutions. The importance of open government data is born from it being a part of citizens' everyday lives, down to the most routine and mundane tasks that are seemingly far removed from government.[citation needed]

The abbreviation FAIR/O data is sometimes used to indicate that the dataset or database in question complies with the principles of FAIR data and carries an explicit data‑capable open license.

Overview

[edit]The concept of open data is not new, but a formalized definition is relatively new. Open data as a phenomenon denotes that governmental data should be available to anyone with a possibility of redistribution in any form without any copyright restriction.[5] One more definition is the Open Definition which can be summarized as "a piece of data is open if anyone is free to use, reuse, and redistribute it—subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and/or share-alike."[6] Other definitions, including the Open Data Institute's "open data is data that anyone can access, use or share," have an accessible short version of the definition but refer to the formal definition.[7] Open data may include non-textual material such as maps, genomes, connectomes, chemical compounds, mathematical and scientific formulae, medical data, and practice, bioscience and biodiversity data.

A major barrier to the open data movement is the commercial value of data. Access to, or re-use of, data is often controlled by public or private organizations. Control may be through access restrictions, licenses, copyright, patents and charges for access or re-use. Advocates of open data argue that these restrictions detract from the common good and that data should be available without restrictions or fees.[citation needed] There are many other, smaller barriers as well.[8]

Creators of data do not consider the need to state the conditions of ownership, licensing and re-use; instead presuming that not asserting copyright enters the data into the public domain. For example, many scientists do not consider the data published with their work to be theirs to control and consider the act of publication in a journal to be an implicit release of data into the commons. The lack of a license makes it difficult to determine the status of a data set and may restrict the use of data offered in an "Open" spirit. Because of this uncertainty it is possible for public or private organizations to aggregate said data, claim that it is protected by copyright, and then resell it.[citation needed]

Major sources

[edit]

Open data can come from any source. This section lists some of the fields that publish (or at least discuss publishing) a large amount of open data.

In science

[edit]The concept of open access to scientific data was established with the formation of the World Data Center system, in preparation for the International Geophysical Year of 1957–1958.[9] The International Council of Scientific Unions (now the International Council for Science) oversees several World Data Centres with the mission to minimize the risk of data loss and to maximize data accessibility.[10]

While the open-science-data movement long predates the Internet, the availability of fast, readily available networking has significantly changed the context of open science data, as publishing or obtaining data has become much less expensive and time-consuming.[11]

The Human Genome Project was a major initiative that exemplified the power of open data. It was built upon the so-called Bermuda Principles, stipulating that: "All human genomic sequence information … should be freely available and in the public domain in order to encourage research and development and to maximize its benefit to society".[12] More recent initiatives such as the Structural Genomics Consortium have illustrated that the open data approach can be used productively within the context of industrial R&D.[13]

In 2004, the Science Ministers of all nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which includes most developed countries of the world, signed a declaration which states that all publicly funded archive data should be made publicly available.[14] Following a request and an intense discussion with data-producing institutions in member states, the OECD published in 2007 the OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding as a soft-law recommendation.[15]

Examples of open data in science:

- data.uni-muenster.de – Open data about scientific artifacts from the University of Muenster, Germany. Launched in 2011.

- Dataverse Network Project – archival repository software promoting data sharing, persistent data citation, and reproducible research.[16]

- linkedscience.org/data – Open scientific datasets encoded as Linked Data. Launched in 2011, ended 2018.[17][18]

- systemanaturae.org – Open scientific datasets related to wildlife classified by animal species. Launched in 2015.[19]

In government

[edit]There are a range of different arguments for government open data.[20][21] Some advocates say that making government information available to the public as machine readable open data can facilitate government transparency, accountability and public participation. "Open data can be a powerful force for public accountability—it can make existing information easier to analyze, process, and combine than ever before, allowing a new level of public scrutiny."[22] Governments that enable public viewing of data can help citizens engage within the governmental sectors and "add value to that data."[23] Open data experts have nuanced the impact that opening government data may have on government transparency and accountability. In a widely cited paper, scholars David Robinson and Harlan Yu contend that governments may project a veneer of transparency by publishing machine-readable data that does not actually make government more transparent or accountable.[24] Drawing from earlier studies on transparency and anticorruption,[25] World Bank political scientist Tiago C. Peixoto extended Yu and Robinson's argument by highlighting a minimal chain of events necessary for open data to lead to accountability:

- relevant data is disclosed;

- the data is widely disseminated and understood by the public;

- the public reacts to the content of the data; and

- public officials either respond to the public's reaction or are sanctioned by the public through institutional means.[26]

Some make the case that opening up official information can support technological innovation and economic growth by enabling third parties to develop new kinds of digital applications and services.[27]

Several national governments have created websites to distribute a portion of the data they collect. It is a concept for a collaborative project in the municipal Government to create and organize culture for Open Data or Open government data.

Additionally, other levels of government have established open data websites. There are many government entities pursuing Open Data in Canada. Data.gov lists the sites of a total of 40 US states and 46 US cities and counties with websites to provide open data, e.g., the state of Maryland, the state of California, US[28] and New York City.[29]

At the international level, the United Nations has an open data website that publishes statistical data from member states and UN agencies,[30] and the World Bank published a range of statistical data relating to developing countries.[31] The European Commission has created two portals for the European Union: the EU Open Data Portal which gives access to open data from the EU institutions, agencies and other bodies[32] and the European Data Portal that provides datasets from local, regional and national public bodies across Europe.[33] The two portals were consolidated to data.europa.eu on April 21, 2021.

Italy is the first country to release standard processes and guidelines under a Creative Commons license for spread usage in the Public Administration. The open model is called the Open Data Management Cycle and was adopted in several regions such as Veneto and Umbria.[34][35][36] Main cities like Reggio Calabria and Genova have also adopted this model.[citation needed][37]

In October 2015, the Open Government Partnership launched the International Open Data Charter, a set of principles and best practices for the release of governmental open data formally adopted by seventeen governments of countries, states and cities during the OGP Global Summit in Mexico.[38]

In July 2024, the OECD adopted Creative Commons CC-BY-4.0 licensing for its published data and reports.[39]

In non-profit organizations

[edit]Many non-profit organizations offer open access to their data, as long it does not undermine their users', members' or third party's privacy rights. In comparison to for-profit corporations, they do not seek to monetize their data. OpenNWT launched a website offering open data of elections.[40] CIAT offers open data to anybody who is willing to conduct big data analytics in order to enhance the benefit of international agricultural research.[41] DBLP, which is owned by a non-profit organization Dagstuhl, offers its database of scientific publications from computer science as open data.[42]

Hospitality exchange services, including Bewelcome, Warm Showers, and CouchSurfing (before it became for-profit) have offered scientists access to their anonymized data for analysis, public research, and publication.[43][44][45][46][47]

Publication of open data

[edit]- arXiv – open-access repository of electronic preprints and postprints (known as e-prints)

- Zenodo – open repository developed under the European OpenAIRE program and operated by CERN

- Figshare – open data and software hosting

- HAL (open archive) – open archive where authors can deposit scholarly documents from all academic fields

- Dryad (repository) – data and software related to science papers

- Open Science Framework – project management and sharing platform

Policies and strategies

[edit]At a small level, a business or research organization's policies and strategies towards open data will vary, sometimes greatly. One common strategy employed is the use of a data commons. A data commons is an interoperable software and hardware platform that aggregates (or collocates) data, data infrastructure, and data-producing and data-managing applications in order to better allow a community of users to manage, analyze, and share their data with others over both short- and long-term timelines.[48][49][50] Ideally, this interoperable cyberinfrastructure should be robust enough "to facilitate transitions between stages in the life cycle of a collection" of data and information resources[48] while still being driven by common data models and workspace tools enabling and supporting robust data analysis.[50] The policies and strategies underlying a data commons will ideally involve numerous stakeholders, including the data commons service provider, data contributors, and data users.[49]

Grossman et al[49] suggests six major considerations for a data commons strategy that better enables open data in businesses and research organizations. Such a strategy should address the need for:

- permanent, persistent digital IDs, which enable access controls for datasets;

- permanent, discoverable metadata associated with each digital ID;

- application programming interface (API)-based access, tied to an authentication and authorization service;

- data portability;

- data "peering," without access, egress, and ingress charges; and

- a rationed approach to users computing data over the data commons.

Beyond individual businesses and research centers, and at a more macro level, countries like Germany[51] have launched their own official nationwide open data strategies, detailing how data management systems and data commons should be developed, used, and maintained for the greater public good.

Arguments for and against

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Opening government data is only a waypoint on the road to improving education, improving government, and building tools to solve other real-world problems. While many arguments have been made categorically[citation needed], the following discussion of arguments for and against open data highlights that these arguments often depend highly on the type of data and its potential uses.

Arguments made on behalf of open data include the following:

- "Data belongs to the human race". Typical examples are genomes, data on organisms, medical science, environmental data following the Aarhus Convention.

- Public money was used to fund the work, and so it should be universally available.[52]

- It was created by or at a government institution (this is common in US National Laboratories and government agencies).

- Facts cannot legally be copyrighted.

- Sponsors of research do not get full value unless the resulting data are freely available.

- Restrictions on data re-use create an anticommons.

- Data are required for the smooth process of running communal human activities and are an important enabler of socio-economic development (health care, education, economic productivity, etc.).[53]

- In scientific research, the rate of discovery is accelerated by better access to data.[54][55]

- Making data open helps combat "data rot" and ensure that scientific research data are preserved over time.[56][57]

- Statistical literacy benefits from open data. Instructors can use locally relevant data sets to teach statistical concepts to their students.[58][59]

- Allowing open data in the scientific community is essential for increasing the rate of discoveries and recognizing significant patterns.[60][55]

It is generally held that factual data cannot be copyrighted.[61] Publishers frequently add copyright statements (often forbidding re-use) to scientific data accompanying publications. It may be unclear whether the factual data embedded in full text are part of the copyright.

While the human abstraction of facts from paper publications is normally accepted as legal there is often an implied restriction on the machine extraction by robots.

Unlike open access, where groups of publishers have stated their concerns, open data is normally challenged by individual institutions.[citation needed] Their arguments have been discussed less in public discourse and there are fewer quotes to rely on at this time.

Arguments against making all data available as open data include the following:

- Government funding may not be used to duplicate or challenge the activities of the private sector (e.g. PubChem).

- Governments have to be accountable for the efficient use of taxpayer's money: If public funds are used to aggregate the data and if the data will bring commercial (private) benefits to only a small number of users, the users should reimburse governments for the cost of providing the data.

- Open data may lead to exploitation of, and rapid publication of results based on, data pertaining to developing countries by rich and well-equipped research institutes, without any further involvement and/or benefit to local communities (helicopter research); similarly, to the historical open access to tropical forests that has led to the misappropriation ("Global Pillage") of plant genetic resources from developing countries.[62]

- The revenue earned by publishing data can be used to cover the costs of generating and/or disseminating the data, so that the dissemination can continue indefinitely.

- The revenue earned by publishing data permits non-profit organizations to fund other activities (e.g. learned society publishing supports the society).

- The government gives specific legitimacy for certain organizations to recover costs (NIST in US, Ordnance Survey in UK).

- Privacy concerns may require that access to data is limited to specific users or to sub-sets of the data.[63]

- Collecting, 'cleaning', managing and disseminating data are typically labour- and/or cost-intensive processes – whoever provides these services should receive fair remuneration for providing those services.

- Sponsors do not get full value unless their data is used appropriately – sometimes this requires quality management, dissemination and branding efforts that can best be achieved by charging fees to users.

- Often, targeted end-users cannot use the data without additional processing (analysis, apps etc.) – if anyone has access to the data, none may have an incentive to invest in the processing required to make data useful (typical examples include biological, medical, and environmental data).

- There is no control to the secondary use (aggregation) of open data.[64]

The paper entitled "Optimization of Soft Mobility Localization with Sustainable Policies and Open Data"[65] argues that open data is a valuable tool for improving the sustainability and equity of soft mobility in cities. The author argues that open data can be used to identify the needs of different areas of a city, develop algorithms that are fair and equitable, and justify the installation of soft mobility resources.

Relation to other open activities

[edit]The goals of the Open Data movement are similar to those of other "Open" movements.

- Open access is concerned with making scholarly publications freely available on the internet. In some cases, these articles include open datasets as well.

- Open specifications are documents describing file types or protocols, where the documents are openly licensed. These specifications are primarily meant to improve different software handling the same file types or protocols, but monopolists forced by law into open specifications might make it more difficult.

- Open content is concerned with making resources aimed at a human audience (such as prose, photos, or videos) freely available.

- Open knowledge. Open Knowledge International argues for openness in a range of issues including, but not limited to, those of open data. It covers (a) scientific, historical, geographic or otherwise (b) Content such as music, films, books (c) Government and other administrative information. Open data is included within the scope of the Open Knowledge Definition, which is alluded to in Science Commons' Protocol for Implementing Open Access Data.[66]

- Open notebook science refers to the application of the Open Data concept to as much of the scientific process as possible, including failed experiments and raw experimental data.[citation needed]

- Open-source software is concerned with the open-source licenses under which computer programs can be distributed and is not normally concerned primarily with data.

- Open educational resources are freely accessible, openly licensed documents and media that are useful for teaching, learning, and assessing as well as for research purposes.

- Open research/open science/open science data (linked open science) means an approach to open and interconnect scientific assets like data, methods and tools with linked data techniques to enable transparent, reproducible and interdisciplinary research.[67]

- Open-GLAM (Galleries, Library, Archives, and Museums)[68] is an initiative and network that supports exchange and collaboration between cultural institutions that support open access to their digitalized collections. The GLAM-Wiki Initiative helps cultural institutions share their openly licensed resources with the world through collaborative projects with experienced Wikipedia editors. Open Heritage Data is associated with Open GLAM, as openly licensed data in the heritage sector is now frequently used in research, publishing, and programming,[69] particularly in the Digital Humanities.

Open Data as commons

[edit]Ideas and definitions

[edit]Formally both the definition of Open Data and commons revolve around the concept of shared resources with a low barrier to access. Substantially, digital commons include Open Data in that it includes resources maintained online, such as data.[70] Overall, looking at operational principles of Open Data one could see the overlap between Open Data and (digital) commons in practice. Principles of Open Data are sometimes distinct depending on the type of data under scrutiny.[71] Nonetheless, they are somewhat overlapping and their key rationale is the lack of barriers to the re-use of data(sets).[71] Regardless of their origin, principles across types of Open Data hint at the key elements of the definition of commons. These are, for instance, accessibility, re-use, findability, non-proprietarily.[71] Additionally, although to a lower extent, threats and opportunities associated with both Open Data and commons are similar. Synthesizing, they revolve around (risks and) benefits associated with (uncontrolled) use of common resources by a large variety of actors.

The System

[edit]Both commons and Open Data can be defined by the features of the resources that fit under these concepts, but they can be defined by the characteristics of the systems their advocates push for. Governance is a focus for both Open Data and commons scholars.[71][70] The key elements that outline commons and Open Data peculiarities are the differences (and maybe opposition) to the dominant market logics as shaped by capitalism.[70] Perhaps it is this feature that emerges in the recent surge of the concept of commons as related to a more social look at digital technologies in the specific forms of digital and, especially, data commons.

Real-life case

[edit]Application of open data for societal good has been demonstrated in academic research works.[72] The paper "Optimization of Soft Mobility Localization with Sustainable Policies and Open Data" uses open data in two ways. First, it uses open data to identify the needs of different areas of a city. For example, it might use data on population density, traffic congestion, and air quality to determine where soft mobility resources, such as bike racks and charging stations for electric vehicles, are most needed. Second, it uses open data to develop algorithms that are fair and equitable. For example, it might use data on the demographics of a city to ensure that soft mobility resources are distributed in a way that is accessible to everyone, regardless of age, disability, or gender. The paper also discusses the challenges of using open data for soft mobility optimization. One challenge is that open data is often incomplete or inaccurate. Another challenge is that it can be difficult to integrate open data from different sources. Despite these challenges, the paper argues that open data is a valuable tool for improving the sustainability and equity of soft mobility in cities.

An exemplification of how the relationship between Open Data and commons and how their governance can potentially disrupt the market logic otherwise dominating big data is a project conducted by Human Ecosystem Relazioni in Bologna (Italy).[73]

This project aimed at extrapolating and identifying online social relations surrounding "collaboration" in Bologna. Data was collected from social networks and online platforms for citizens collaboration. Eventually data was analyzed for the content, meaning, location, timeframe, and other variables. Overall, online social relations for collaboration were analyzed based on network theory. The resulting dataset have been made available online as Open Data (aggregated and anonymized); nonetheless, individuals can reclaim all their data. This has been done with the idea of making data into a commons. This project exemplifies the relationship between Open Data and commons, and how they can disrupt the market logic driving big data use in two ways. First, it shows how such projects, following the rationale of Open Data somewhat can trigger the creation of effective data commons. The project itself was offering different types of support to social network platform users to have contents removed. Second, opening data regarding online social networks interactions has the potential to significantly reduce the monopolistic power of social network platforms on those data.

Funders' mandates

[edit]Several funding bodies that mandate Open Access also mandate Open Data. A good expression of requirements (truncated in places) is given by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR):[74]

- to deposit bioinformatics, atomic and molecular coordinate data, and experimental data into the appropriate public database immediately upon publication of research results.

- to retain original data sets for at least five years after the grant. This applies to all data, whether published or not.

Other bodies promoting the deposition of data and full text include the Wellcome Trust. An academic paper published in 2013 advocated that Horizon 2020 (the science funding mechanism of the EU) should mandate that funded projects hand in their databases as "deliverables" at the end of the project so that they can be checked for third-party usability and then shared.[75]

See also

[edit]- Open knowledge

- Free content

- Openness

- Committee on Data of the International Science Council

- CKAN - Comprehensive Knowledge Archive Network

- Creative Commons license

- Data curation

- Data governance

- Data management

- Data publishing

- Data sharing

- Demand-responsive transport

- Digital preservation

- FAIR data principles

- International Open Data Day

- Linked data and Linked open data

- Open energy system databases

- Urban informatics

- Wikibase

- Wikidata

- List of datasets for machine-learning research

- Open Standard

- Digital public goods

References

[edit]- ^ "What is open?". okfn.org. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Open Definition 2.1 - Open Definition - Defining Open in Open Data, Open Content and Open Knowledge". opendefinition.org. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Auer, S. R.; Bizer, C.; Kobilarov, G.; Lehmann, J.; Cyganiak, R.; Ives, Z. (2007). "DBpedia: A Nucleus for a Web of Open Data". The Semantic Web. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 4825. pp. 722–735. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-76298-0_52. ISBN 978-3-540-76297-3. S2CID 7278297.

- ^ Kitchin, Rob (2014). The Data Revolution. London: Sage. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-4462-8748-4.

- ^ Kassen, Maxat (1 October 2013). "A promising phenomenon of open data: A case study of the Chicago open data project". Government Information Quarterly. 30 (4): 508–513. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2013.05.012. ISSN 0740-624X.

- ^ See Open Definition home page and the full Open Definition

- ^ "What is 'open data' and why should we care? – The ODI". 3 November 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Gomes, Dylan G. E.; Pottier, Patrice; Crystal-Ornelas, Robert; Hudgins, Emma J.; Foroughirad, Vivienne; Sánchez-Reyes, Luna L.; Turba, Rachel; Martinez, Paula Andrea; Moreau, David; Bertram, Michael G.; Smout, Cooper A.; Gaynor, Kaitlyn M. (2022). "Why don't we share data and code? Perceived barriers and benefits to public archiving practices". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 289 (1987) 20221113. doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.1113. PMC 9682438. PMID 36416041.

- ^ Committee on Scientific Accomplishments of Earth Observations from Space, National Research Council (2008). Earth Observations from Space: The First 50 Years of Scientific Achievements. The National Academies Press. p. 6. Bibcode:2008eosf.book.....N. doi:10.17226/11991. ISBN 978-0-309-11095-2. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ World Data System (27 September 2017). "Data Sharing Principles". www.icsu-wds.org. ICSU-WDS (International Council for Science - World Data Service). Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (12 December 2017). "Open data, open review and open dialogue in making social sciences plausible". Nature: Scientific Data Updates. arXiv:1712.04801. Bibcode:2017arXiv171204801V. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ^ Human Genome Project, 1996. Summary of Principles Agreed Upon at the First International Strategy Meeting on Human Genome Sequencing (Bermuda, 25–28 February 1996)

- ^ Perkmann, Markus; Schildt, Henri (2015). "Open Data Partnerships between Firms and Universities: The Role of Boundary Organizations". Research Policy. 44 (5): 1133–1143. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.12.006. hdl:10044/1/19450.

- ^ OECD Declaration on Open Access to publicly funded data Archived 20 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pilat, D.; Fukasaku (29 June 2007). "OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding". Data Science Journal. 6: 4–11. doi:10.2481/dsj.6.OD4. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ "Dataverse Network Project". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ "Data". Linked Science. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Kauppinen, Tomi; de Espindola, Giovanna Mira (2011). Linked Open Science—Communicating, Sharing and Evaluating Data, Methods and Results for Executable Papers (PDF). International Conference on Computational Science, ICCS 2011. Vol. 4. Procedia Computer Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "Home". Wildlife DataSets, Animal Population DataSets and Conservation Research Projects, Surveys - Systema Naturae. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Gray, Jonathan (3 September 2014). Towards a Genealogy of Open Data. General Conference of the European Consortium for Political Research in Glasgow. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2605828. SSRN 2605828 – via SSRN.

- ^ Brito, Jerry (21 October 2007). "Hack, Mash, & Peer: Crowdsourcing Government Transparency". Columbia Science & Technology Law Review. 9: 119. doi:10.2139/SSRN.1023485. S2CID 109457712. SSRN 1023485.

- ^ Yu, Harlan; Robinson, David G. (28 February 2012). "The New Ambiguity of 'Open Government'". UCLA Law Review Discourse. 59. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2012489. SSRN 2012489 – via Social Science Research Network.

- ^ Robinson, David G.; Yu, Harlan; Zeller, William P.; Felten, Edward W. (1 January 2009). "Government Data and the Invisible Hand". Yale Journal of Law & Technology. 11. Rochester, NY. SSRN 1138083 – via Social Science Research Network.

- ^ uclalaw (8 August 2012). "The New Ambiguity of "Open Government"". UCLA Law Review. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Lindstedt, Catharina; Naurin, Daniel (June 2010). "Transparency is not Enough: Making Transparency Effective in Reducing Corruption". International Political Science Review. 31 (3): 301–322. doi:10.1177/0192512110377602. ISSN 0192-5121. S2CID 154948461.

- ^ uclalaw (2 May 2013). "The Uncertain Relationship Between Open Data and Accountability: A Response to Yu and Robinson's The New Ambiguity of "Open Government"". UCLA Law Review. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "The Economic Impact of Open Data: Opportunities for value creation in Europe". data.europa.eu. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "California Open Data Portal". data.ca.gov. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "NYC Open Data". City of New York. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "UNdata". data.un.org. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Open Data | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Data.europa.eu". Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Home | Open Data Portal". data.europa.eu. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Open Data Management Cycle" (in Italian).

- ^ "Linee guida per l'ecosistema regionale veneto dei dati aperti (Open Data)" (in Italian).

- ^ "Modello Operativo Open Data (MOOD) Umbria" (in Italian).

- ^ "Linee guida programmatiche della Città Metropolitana di Genova" (PDF) (in Italian).

- ^ "The Open Data Charter: A Roadmap for Using a Global Resource". The Huffington Post. 27 October 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ OECD (4 July 2024). "OECD data, publications and analysis become freely accessible — Press release". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Paris, France. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Green, Arthur C. (17 September 2019). "OpenNWT announces launch of new election information website". My Yellowknife Now.

- ^ Oyuela, Andrea; Walmsley, Thea; Walla, Katherine (30 December 2019). "120 Organizations Creating a New Decade for Food". Food Tank. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ "dblp: How can I download the whole dblp dataset?". dblp.uni-trier.de. Dagstuhl. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Victor, Patricia; Cornelis, Chris; De Cock, Martine; Herrera-Viedma, Enrique (2010). "Bilattice-based aggregation operators for gradual trust and distrust". World Scientific Proceedings Series on Computer Engineering and Information Science. World Scientific: 505–510. doi:10.1142/9789814324700_0075. ISBN 978-981-4324-69-4. S2CID 5748283.

- ^ Dandekar, Pranav. Analysis & Generative Model for Trust Networks (PDF). Stanford Network Analysis Project (Report). Stanford University.

- ^ Overgoor, Jan; Wulczyn, Ellery; Potts, Christopher (20 May 2012). "Trust Propagation with Mixed-Effects Models". Sixth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media.

- ^ Lauterbach, Debra; Truong, Hung; Shah, Tanuj; Adamic, Lada (August 2009). "Surfing a Web of Trust: Reputation and Reciprocity on CouchSurfing.com". 2009 International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering. Vol. 4. pp. 346–353. doi:10.1109/CSE.2009.345. ISBN 978-1-4244-5334-4. S2CID 12869279.

- ^ Tagiew, Rustam; Ignatov, Dmitry. I; Delhibabu, Radhakrishnan (2015). "Hospitality Exchange Services as a Source of Spatial and Social Data?". 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshop (ICDMW). IEEE. pp. 1125–1130. arXiv:1412.8700. doi:10.1109/ICDMW.2015.239. ISBN 978-1-4673-8493-3. S2CID 8196598.

- ^ a b National Science Foundation (September 2005). "Long-Lived Digital Data Collections: Enabling Research and Education in the 21st Century" (PDF). National Science Foundation. p. 23. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Grossman, Robert L.; Heath, Allison; Murphy, Mark; Patterson, Maria; Wells, Walt (2016). "A Case for Data Commons: Toward Data Science as a Service". Computing in Science & Engineering. 18 (5): 10–20. arXiv:1604.02608. Bibcode:2016CSE....18e..10G. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2016.92. ISSN 1521-9615. PMC 5636009. PMID 29033693.

- ^ a b Grossman, R.L. (23 April 2019). "How Data Commons Can Support Open Science". Sage Bionetworks. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ BMI (7 July 2021). Open-Data-Strategie der Bundesregierung — BMI21030 [Open data strategy of the German Federal Government — BMI21030] (PDF) (in German). Berlin, Germany: Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (BMI). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ "On the road to open data, by Ian Manocha". Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2011.

- ^ "Big Data for Development: From Information- to Knowledge Societies", Martin Hilbert (2013), SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 2205145. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; https://ssrn.com/abstract=2205145

- ^ How to Make the Dream Come True[permanent dead link] argues in one research area (Astronomy) that access to open data increases the rate of scientific discovery.

- ^ a b Gomes Dylan G. E. 2025 How will we prepare for an uncertain future? The value of open data and code for unborn generations facing climate change Proc. R. Soc. B.29220241515

- ^ Khodiyar, Varsha (19 May 2014). "Stopping the rot: ensuring continued access to scientific data, irrespective of age". F1000 Research. F1000. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ^ Magee AF, May MR, Moore BR (24 October 2014). "The dawn of open access to phylogenetic data". PLOS ONE. 9 (10) e110268. arXiv:1405.6623. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k0268M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0110268. PMC 4208793. PMID 25343725.

- ^ Rivera, Roberto; Marazzi, Mario; Torres, Pedro (19 June 2019). "Incorporating Open Data Into Introductory Courses in Statistics". Journal of Statistics Education. 27 (3). Taylor and Francis: 198–207. arXiv:1906.03762. doi:10.1080/10691898.2019.1669506. S2CID 182952595. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Rivera, Roberto (5 February 2020). Principles of Managerial Statistics and Data Science. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-48641-1.

- ^ Gewin, V. (2016). "Data sharing: An open mind on open data". Nature. 529 (7584): 117–119. doi:10.1038/NJ7584-117A. PMID 26744755. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Towards a Science Commons Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine includes an overview of the basis of openness in science data.

- ^ Low, A. (2001). The Third Revolution: Plant Genetic Resources in Developing Countries and China: Global Village or Global Pillage?. International Trade & Business Law Annual Vol VI. ISBN 978-1-84314-087-0. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Zuiderwijk, Anneke; Janssen, Marijn (18 June 2014). "The negative effects of open government data - investigating the dark side of open data". Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research. dg.o '14. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 147–152. doi:10.1145/2612733.2612761. ISBN 978-1-4503-2901-9. S2CID 14440894.

- ^ Sharif, Naubahar; Ritter, Waltraut; Davidson, Robert L; Edmunds, Scott C (31 December 2018). "An Open Science 'State of the Art' for Hong Kong: Making Open Research Data Available to Support Hong Kong Innovation Policy". Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia. 17 (2): 200–221. doi:10.17477/JCEA.2018.17.2.200.

- ^ Kleisarchaki, Sofia; Gürgen, Levent; Mitike Kassa, Yonas; Krystek, Marcin; González Vidal, Daniel (12 June 2022). "Optimization of Soft Mobility Localization with Sustainable Policies and Open Data". 2022 18th International Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE). pp. 1–8. doi:10.1109/IE54923.2022.9826779. ISBN 978-1-6654-6934-0. S2CID 250595935.

- ^ "Protocol for Implementing Open Access Data". Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ Kauppinen, T.; Espindola, G. M. D. (2011). "Linked Open Science-Communicating, Sharing and Evaluating Data, Methods and Results for Executable Papers". Procedia Computer Science. 4: 726–731. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2011.04.076.

- ^ "Open GLAM". Wikimedia Meta-Wiki.

- ^ Henriette Roued (2020). Open Heritage Data: An introduction to research, publishing and programming with open data in the heritage sector. Facet Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78330-360-1. OL 29397859M. Wikidata Q111293389.

- ^ a b c Dulong de Rosnay, Mélanie; Stalder, Felix (17 December 2020). "Digital commons". Internet Policy Review. 9 (4). doi:10.14763/2020.4.1530. ISSN 2197-6775. S2CID 240800967.

- ^ a b c d van Loenen, Bastiaan; Vancauwenberghe, Glenn; Crompvoets, Joep; Dalla Corte, Lorenzo (2018). Open Data Exposed. Information Technology and Law Series. Vol. 30. T.M.C. Asser Press. pp. 1–10. doi:10.1007/978-94-6265-261-3_1. eISSN 2215-1966. ISBN 978-94-6265-260-6. ISSN 1570-2782.

- ^ Kleisarchaki, Sofia; Gürgen, Levent; Mitike Kassa, Yonas; Krystek, Marcin; González Vidal, Daniel (1 June 2022). "Optimization of Soft Mobility Localization with Sustainable Policies and Open Data". 2022 18th International Conference on Intelligent Environments (IE). pp. 1–8. doi:10.1109/IE54923.2022.9826779. ISBN 978-1-6654-6934-0. S2CID 250595935.

- ^ "HUB Human Ecosystems Bologna" (PDF). Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) draft policy on access to research outputs". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- ^ Galsworthy, M.; McKee, M. (2013). "Galsworthy, M.J. & McKee, M. (2013). Europe's "Horizon 2020" science funding programme: How is it shaping up? Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. doi: 10.1177/1355819613476017". Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 18 (3): 182–185. doi:10.1177/1355819613476017. PMC 4107840. PMID 23595575. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

External links

[edit]- Open Data – An Introduction – from the Open Knowledge Foundation

- Video of Tim Berners-Lee at TED (conference) 2009 calling for "Raw Data Now"

- Six minute Video of Tim Berners-Lee at TED (conference) 2010 showing examples of open data

- G8 Open Data Charter

- Towards a Genealogy of Open Data – research paper tracing different historical threads contributing to current conceptions of open data.

Open data

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Principles

Core Concepts and Definitions

Open data consists of information in digital formats that can be freely accessed, used, modified, and shared by anyone, subject only to measures that preserve its origin and ongoing openness.[11] This formulation, from the Open Definition version 2.1 adopted in 2019 by the Open Knowledge Foundation, establishes a baseline for openness applicable to data, content, and knowledge, requiring conformance across legal, normative, and technical dimensions.[11] Legally, data must reside in the public domain or carry an open license that permits unrestricted reuse, redistribution, and derivation for any purpose, including commercial applications, without field-of-endeavor discrimination or fees beyond marginal reproduction costs.[11] Normatively, such licenses must grant equal rights to all parties and remain irrevocable, with permissible conditions limited to attribution, share-alike provisions to ensure derivative works stay open, and disclosure of modifications.[11] Technically, open data demands machine readability, meaning it must be structured in formats processable by computers without undue barriers, using non-proprietary specifications compatible with libre/open-source software.[11] Access must occur via the internet in complete wholes, downloadable without payment or undue technical hurdles, excluding real-time data streams or physical artifacts.[11] These criteria distinguish open data from merely public or accessible data, as the latter may impose royalties, discriminatory terms, or encrypted/proprietary encumbrances that hinder reuse.[11] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reinforces this by defining open data as datasets releasable for access and reuse by any party absent technical, legal, or organizational restrictions, underscoring its role in enabling empirical analysis and economic value creation as of 2019 assessments.[12] Complementary frameworks, such as the World Bank's 2016 Open Government Data Toolkit, emphasize that open data must be primary (collected at source with maximal detail), timely, and non-proprietary to support accountability and innovation without vendor lock-in.[13] The eight principles of open government data, articulated in 2007 by advocates including the Sunlight Foundation, further specify completeness (all related public data included), accessibility (via standard protocols), and processability (structured for automated handling), ensuring data serves as a foundational resource rather than siloed information.[2] These elements collectively prioritize causal utility—data's potential to inform decisions through direct manipulation—over mere availability, with empirical studies from 2022 confirming that adherence correlates with higher reuse rates in public sectors.[14]Foundational Principles and Standards

The Open Definition, established by the Open Knowledge Foundation in 2005 and updated to version 2.1 in 2020, provides the core criterion for openness in data: it must be freely accessible, usable, modifiable, and shareable for any purpose, subject only to minimal requirements ensuring provenance and continued openness are preserved.[11] This definition draws from open source software principles but adapts them to data and content, emphasizing legal and technical freedoms without proprietary restrictions. Compliance with the Open Definition ensures data avoids paywalls, discriminatory access, or clauses limiting commercial reuse, fostering broad societal benefits like innovation and accountability.[15] Building on this, the eight principles of open government data, formulated by advocates in December 2007, outline practical standards for public sector data release. These include completeness (all public data made available), primacy (raw, granular data at the source rather than aggregates), timeliness (regular updates reflecting changes), ease of access (via multiple channels without barriers), machine readability (structured formats over PDFs or images), non-discrimination (no usage fees or restrictions beyond license terms), use of common or open standards (to avoid vendor lock-in), and permanence (indefinite availability without arbitrary withdrawal).[2] These principles prioritize causal efficacy in data utility, enabling empirical analysis and reuse without intermediaries distorting primary sources, though implementation varies due to institutional inertia or privacy constraints not inherent to openness itself. For scientific and research data, the FAIR principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—emerged in 2016 as complementary guidelines focused on digital object management. Findability requires unique identifiers and rich metadata for discovery; accessibility mandates protocols for retrieval, even behind authentication if openly retrievable; interoperability demands standardized formats and vocabularies for integration; reusability emphasizes clear licenses, provenance documentation, and domain-relevant descriptions.[16] Published in Scientific Data, these principles address empirical reproducibility in research, where non-FAIR data leads to siloed knowledge and wasted resources, but they do not equate to full openness without permissive licensing.[17] Licensing standards reinforce these foundations, with Open Data Commons providing templates like the Public Domain Dedication and License (PDDL) for waiving rights and the Open Database License (ODbL) for share-alike requirements preserving openness in derivatives.[18] Approved licenses under the Open Definition, such as Creative Commons CC0 or CC-BY, ensure legal reusability; technical standards favor machine-readable formats like CSV, JSON, or RDF over proprietary ones to enable automated processing.[19] Non-conformant licenses, often from biased institutional policies favoring control over transparency, undermine these standards despite claims of "openness," as verified by conformance lists maintained by the Open Knowledge Foundation.[20]Historical Development

Origins in Scientific Practice

The empirical nature of modern scientific inquiry, emerging in the 17th century, necessitated data sharing to enable replication, verification, and cumulative progress, distinguishing it from prior speculative traditions. Scientists disseminated raw observations and measurements through letters, academies, and early periodicals, fostering communal evaluation over individual authority. This practice aligned with Francis Bacon's advocacy in Novum Organum (1620) for collaborative induction based on shared experiments, countering secrecy in alchemical traditions.[21] The Royal Society of London, chartered in 1660, institutionalized these norms by prioritizing empirical evidence, as reflected in its motto Nullius in verba. Its Philosophical Transactions, launched in 1665 as the world's first scientific journal, routinely published detailed datasets, including astronomical tables and experimental records, to substantiate findings and invite critique. Such disclosures, often involving precise measurements like planetary positions or chemical yields, allowed peers to test claims independently, accelerating discoveries in physics and biology.[22][23] Astronomy provided early exemplars of systematic data exchange, with telescopic observations shared post-1608 to map celestial motions accurately. Tycho Brahe's meticulously recorded stellar and planetary data, compiled from 1576 to 1601, were accessed by Johannes Kepler, enabling the formulation of elliptical orbit laws in Astronomia Nova (1609). This transfer underscored data's role as a communal resource, yielding predictive models unattainable by isolated efforts. Similarly, meteorology advanced through 19th-century international pacts; the 1873 Vienna Congress established the International Meteorological Committee, standardizing daily weather reports from thousands of stations—such as 1,632 in India by 1901—for global pattern analysis.[24][25][26] These precedents laid groundwork for field-specific repositories, as in 20th-century "big science" projects where instruments like particle accelerators generated vast datasets requiring shared access for analysis, prefiguring digital open data infrastructures.[25]Rise of Institutional Initiatives

The rise of institutional initiatives in open data gained significant traction in the mid-2000s, as governments and international bodies formalized policies to promote the release and reuse of public sector information. The European Union's Directive 2003/98/EC on the re-use of public sector information (PSI Directive) marked an early milestone, establishing a legal framework requiring member states to make documents available for reuse under fair, transparent, and non-discriminatory conditions, thereby facilitating access to raw data held by public authorities.[27] This directive, initially focused on commercial reuse rather than full openness, laid essential groundwork by addressing barriers like proprietary formats and charging policies, influencing subsequent open data mandates across Europe.[28] In the United States, institutional momentum accelerated following the December 2007 formulation of eight principles for open government data at a Sebastopol, California, convening of experts, which emphasized machine-readable, timely, and license-free data to enable public innovation.[4] President Barack Obama's January 21, 2009, memorandum on transparency and open government directed federal agencies to prioritize openness, culminating in the December 2009 Open Government Directive that required agencies to publish high-value datasets in accessible formats within 45 days where feasible.[4] The launch of Data.gov on May 21, 2009, operationalized these efforts by providing a centralized portal, starting with 47 datasets and expanding to over 100,000 by 2014 from 227 agencies.[4] These U.S. actions spurred domestic agency compliance and inspired global emulation, with open data portals proliferating worldwide by the early 2010s.[29] Parallel developments occurred in other jurisdictions, reflecting a broader institutional shift toward data as a public good. The United Kingdom's data.gov.uk portal launched in January 2010, aggregating non-personal data from central government departments and local authorities to support transparency and economic reuse.[30] Internationally, the Open Government Partnership, initiated in 2011 with eight founding nations including the U.S. and U.K., committed members to proactive disclosure of government-held data.[3] By 2013, the G8 Open Data Charter, endorsed by leaders from major economies, standardized principles for high-quality, accessible data release, while the U.S. issued an executive order making open, machine-readable formats the default for federal information, further embedding institutional practices.[4] These initiatives, often driven by executive mandates rather than legislative consensus, demonstrated causal links between policy directives and increased data availability, though implementation varied due to concerns over privacy, resource costs, and data quality.[29] Academic and research institutions also advanced open data through coordinated repositories and funder requirements, complementing government efforts. For instance, the National Science Foundation's 2011 data management plan mandate for grant proposals required researchers to outline strategies for data sharing, fostering institutional cultures of openness in U.S. universities.[31] Similarly, the European Commission's Horizon 2020 program (2014–2020) incentivized open access to research data via the Open Research Data Pilot, expanding institutional participation beyond scientific norms into structured policies.[32] These measures addressed reproducibility challenges in fields like biosciences, where surveys indicated growing adoption of data-sharing practices by the mid-2010s, albeit constrained by infrastructure gaps and incentive misalignments.[33] Overall, the era's initiatives shifted open data from ad hoc scientific sharing to scalable institutional systems, evidenced by the OECD's observation of over 250 national and subnational portals by the mid-2010s.[13]Contemporary Expansion and Global Adoption

In the 2020s, open data initiatives expanded through strengthened policy frameworks and international coordination, with governments prioritizing data release to support economic innovation and public accountability. The European Union's Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on open data and the re-use of public sector information, transposed by member states by July 2021, required proactive publication of high-value datasets in domains including geospatial information, earth observation, environment, meteorology, and statistics on companies and ownership. This built on prior public sector information directives, aiming to create a unified European data market, and generated an estimated economic impact of €184 billion in direct and indirect value added as of 2018, with forecasts projecting growth to €199.51–€334.21 billion by 2025 through enhanced re-use in sectors like transport and agriculture.[34][28] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) tracked this momentum via its 2023 Open, Useful, and Re-usable government Data (OURdata) Index, evaluating 40 countries on data availability (55% weight), accessibility (15%), reusability conditions (15%), and government support for re-use (15%). The OECD average composite score rose, signaling broader maturity, with top performers—South Korea (score 0.89), France (0.87), and Poland (0.84)—excelling through centralized portals, machine-readable formats, and stakeholder consultations that boosted real-world applications like urban planning and environmental monitoring. Non-OECD adherents such as Colombia and Brazil also advanced, reflecting diffusion to emerging economies via bilateral aid and multilateral commitments like the G20 Open Data Charter.[35][36] In North America, the United States reinforced federal open data under the 2018 OPEN Government Data Act, which codified requirements for machine-readable formats and public dashboards; by 2025, the General Services Administration's updated Open Data Plan emphasized improved governance, cataloging over 300,000 datasets on data.gov to facilitate cross-agency collaboration and private-sector analytics. Canada's 2021–2025 Action Plan on Open Government similarly prioritized inclusive data strategies, integrating Indigenous knowledge into releases for sustainable development. Globally, adoption proliferated via national portals—exemplified by India's Open Government Data Platform (launched 2012 but scaled in the 2020s with over 5,000 datasets)—and international repositories like the World Bank's data portal, which by 2025 hosted comprehensive indicators across 200+ economies to track Sustainable Development Goals.[37][38] Research and scientific domains paralleled governmental trends, with funder policies accelerating open data mandates; for instance, the Springer Nature 2023 State of Open Data report documented rising deposit rates in repositories, attributing growth to Plan S (effective 2021) and NIH Data Management and Sharing Policy (January 2023), which required public accessibility for federally funded projects and yielded over 1 million datasets in platforms like Figshare and Zenodo by mid-decade. Challenges persisted, including uneven implementation in low-income regions due to infrastructure gaps, yet causal drivers like pandemic-era data needs (e.g., COVID-19 dashboards) underscored open data's role in causal inference for policy, with empirical evidence from OECD analyses linking higher openness scores to 10–20% gains in data-driven economic outputs.[39]Sources and Providers

Public Sector Contributions

The public sector, encompassing national, regional, and local governments, has been a primary generator and provider of open data, leveraging its mandate to collect extensive administrative, environmental, economic, and demographic information for policy-making and service delivery. By releasing this data under permissive licenses, governments aim to foster transparency, enable public scrutiny of expenditures and operations, and stimulate economic innovation through third-party reuse. Initiatives often stem from executive orders or legislative mandates requiring data publication in machine-readable formats, with portals aggregating datasets for accessibility. Economic analyses estimate that open government data could unlock trillions in value; for instance, a World Bank report projects $3-5 trillion annually across seven U.S. sectors from enhanced data reuse.[7] However, implementation varies, with global assessments like the Open Data Barometer indicating that only about 7% of surveyed government data meets full openness criteria, often due to format limitations or proprietary restrictions.[40] In the United States, the federal government pioneered large-scale open data portals with the launch of Data.gov on May 21, 2009, initiated by Federal CIO Vivek Kundra following President Barack Obama's January 21, 2009, memorandum on transparency and open government.[41] [42] The site initially offered 47 datasets but expanded to over 185,000 by aggregating agency contributions, supported by the 2019 OPEN Government Data Act, which mandates proactive release of non-sensitive data in standardized formats like CSV and JSON.[43] State and local governments have followed suit, with examples including New York City's NYC Open Data portal, which has facilitated applications in urban planning and public health analytics. These efforts prioritize federal leadership in data governance, though critics note uneven quality and completeness across datasets.[37] The European Union has advanced open data through harmonized directives promoting the reuse of public sector information (PSI). The inaugural PSI Directive (2003/98/EC) established a framework for commercial and non-commercial reuse of government-held data, revised in 2013 to encourage dynamic data provision and open licensing by default.[28] This culminated in the 2019 Open Data Directive (EU 2019/1024), effective July 16, 2019, which mandates high-value datasets—such as geospatial, environmental, and company registries—to be released freely, aiming to bolster the EU data economy and AI development while ensuring fair competition.[44] Member states implement via national portals, like France's data.gouv.fr, contributing to OECD rankings where France scores highly for policy maturity and dataset availability.[45] The directive's impact includes increased cross-border data flows, though enforcement relies on national transposition, leading to variability; for example, only select datasets achieve real-time openness.[46] The United Kingdom has been an early and proactive contributor, launching data.gov.uk in 2010 to centralize datasets from central, local, and devolved governments under the Open Government Licence (OGL), which permits broad reuse with minimal restrictions.[47] This built on the 2012 Public Sector Transparency Board recommendations and aligns with the National Data Strategy, emphasizing data as infrastructure for innovation and public services.[48] By 2024, the portal hosts thousands of datasets, supporting applications in transport optimization and economic forecasting, while the UK's Open Government Partnership action plans integrate open data for accountability in contracting and aid.[49] Globally, other nations like South Korea and Estonia lead in OECD metrics for comprehensive policies, with Korea excelling in data availability scores due to integrated national platforms.[36] These public efforts collectively drive a shift toward "open by default," though sustained impact requires addressing interoperability and privacy safeguards under frameworks like GDPR.[45]Academic and Research Repositories

Academic and research repositories constitute specialized platforms designed for the deposit, curation, preservation, and dissemination of datasets, code, and supplementary materials generated in scholarly investigations, thereby underpinning reproducibility and interdisciplinary reuse in open science. These systems typically adhere to FAIR principles—findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable—by assigning persistent identifiers such as DOIs and enforcing metadata standards like Dublin Core or DataCite schemas.[50] Unlike proprietary archives, many operate on open-source software, mitigating vendor lock-in and enabling institutional customization, which has accelerated adoption amid funder requirements for data management plans since policies like the 2023 NIH Data Management and Sharing framework.[50] By centralizing verifiable empirical outputs, they counter selective reporting biases prevalent in peer-reviewed literature, where non-shared data can obscure causal inferences or inflate effect sizes, as evidenced by replication failures in psychology and biomedicine exceeding 50% in meta-analyses.[51] Prominent generalist repositories include Zenodo, developed by CERN and the OpenAIRE consortium, which supports uploads of datasets, software, and multimedia across disciplines with no file size limits beyond practical storage constraints. Established in 2013, Zenodo had hosted over 3 million records and more than 1 petabyte of data by 2023, attracting 25 million annual visits and facilitating compliance with European Horizon program mandates for open outputs.[52] Similarly, the Harvard Dataverse Network, built on open-source Dataverse software originating from Harvard's Institute for Quantitative Social Science in 2006, maintains the largest assemblage of social science datasets worldwide, open to global depositors and emphasizing version control and granular access permissions.[53] It processes thousands of deposits annually, with features for tabulating reuse metrics to quantify scholarly impact beyond traditional citations.[54] Domain-specific and curated options further diversify availability; Dryad Digital Repository, a nonprofit initiative launched in 2008, specializes in data tied to peer-reviewed articles, partnering with over 100 journals to automate submission pipelines and enforce quality checks for completeness and usability.[55] It accepts diverse formats while prioritizing human-readable documentation, having preserved millions of files through community governance that sustains operations via publication fees and grants.[56] Figshare, operated by Digital Science since 2011, targets supplementary materials like figures and raw datasets, reporting over 80,000 citations of its content and providing analytics on views, downloads, and altmetrics to evidence reuse.[57] Institutional repositories, such as those at universities, integrate these functions locally, leveraging campus IT for tailored support and amplifying discoverability through federated searches via registries like re3data.org, which catalogs over 2,000 global entries as of 2025.[58] From 2023 to 2025, these repositories have expanded amid escalating open science imperatives, with usage surging due to policies from bodies like the NSF and ERC requiring public data access for grant eligibility, thereby enhancing causal validation through independent reanalysis.[59] Empirical studies indicate that deposited data in such platforms correlates with 20-30% higher citation rates for associated papers, attributable to verifiable transparency rather than mere accessibility, though uptake remains uneven in humanities versus STEM fields due to data granularity challenges.[60] Challenges persist, including uneven enforcement against data fabrication—despite checksums and provenance tracking—and biases in repository governance favoring high-volume disciplines, yet their proliferation has empirically reduced barriers to meta-research, enabling systematic scrutiny of institutional claims in academia.[51]Private Sector Involvement

Private companies participate in open data ecosystems by releasing proprietary datasets under permissive licenses, hosting public datasets on their infrastructure, and leveraging government-released open data for product development and revenue generation. This involvement extends to collaborations with public entities and nonprofits to share anonymized data addressing societal issues such as public health and urban planning. Empirical analyses indicate that such activities enable firms to create economic value while contributing to broader innovation, though competitive concerns and data privacy risks often limit full disclosure.[61][62] Notable releases include Foursquare's FSQ OS Places dataset, made generally available on November 19, 2024, comprising over 100 million points of interest (POIs) across 200+ countries under the Apache 2.0 license to support geospatial applications.[63] Similarly, NVIDIA released an open-source physical AI dataset on March 18, 2025, containing 15 terabytes of data including 320,000 robotics training trajectories and Universal Scene Description assets, hosted on Hugging Face to accelerate advancements in robotics and autonomous vehicles.[64] In the utilities sector, UK Power Networks published substation noise data in 2022 via an open platform to mitigate pollution risks and inform policy.[62] Tech firms have also shared mobility and health data for public benefit. Uber's Movement platform provides anonymized trip data, including travel times and heatmaps, for cities like Madrid and Barcelona to support urban planning.[65] Meta's Data for Good initiative offers tools with anonymized population density and mobility datasets to aid research and service improvements.[65] Google Health disseminates aggregated COVID-19 datasets and AI models for diagnostics.[65] In healthcare, Microsoft collaborated with the 29 Foundation on HealthData@29, launched around 2022, to share anonymized datasets from partners like HM Hospitals for COVID-19 research.[65] Infrastructure providers like Amazon Web Services facilitate access through the Open Data Sponsorship Program, which covered costs for 66 new or updated datasets as of July 14, 2025, contributing to over 300 petabytes of publicly available data optimized for cloud use.[66] During the COVID-19 pandemic, 11 private companies contributed data to Opportunity Insights in 2021 for real-time economic tracking, yielding insights such as a $377,000 cost per job preserved under stimulus policies.[62] The National Underground Asset Register in the UK, involving 30 companies since post-2017, aggregates subsurface data to prevent infrastructure conflicts.[62] Firms extensively utilize open government data for commercial purposes; the Open Data 500 study identified hundreds of U.S. companies in 2015 that built products and services from such sources, spanning sectors like transportation and finance.[67] Economic modeling attributes substantial gains to these efforts, with McKinsey estimating that open health data alone generates over $300 billion annually through private sector efficiencies and innovations.[68] Broader open data sharing could unlock 1-5% of GDP by 2030 via new revenue streams and reputation enhancements for participating firms.[62] Despite these contributions, private sector engagement remains selective, constrained by risks to intellectual property and market position.[62]Technical Frameworks

Data Standards and Formats

Data standards and formats in open data emphasize machine readability, non-proprietary structures, and interoperability to enable broad reuse without technical barriers. These standards promote formats that are platform-independent and publicly documented, avoiding vendor lock-in and ensuring data can be processed by diverse tools.[69] Organizations like the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) provide best practices, recommending the use of persistent identifiers, content negotiation for multiple representations, and adherence to web standards for data publication.[70] Common file formats for open data include CSV (Comma-Separated Values), which stores tabular data in plain text using delimiters, making it lightweight and compatible with spreadsheets and statistical software; as of 2023, CSV remains a baseline recommendation for initial open data releases due to its simplicity and low barrier to entry.[71] JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) supports hierarchical and nested structures, ideal for APIs and web services, with its human-readable syntax facilitating parsing in programming languages like Python and JavaScript.[72] XML (Extensible Markup Language) enables detailed markup for complex, self-descriptive data, though its verbosity can increase file sizes compared to JSON.[73] For enhanced semantic interoperability, RDF (Resource Description Framework) represents data as triples linking subjects, predicates, and objects, serialized in formats such as Turtle for compactness or JSON-LD for web integration; W3C standards like RDF promote linked data by using URIs as global identifiers, allowing datasets to reference external resources.[70] Cataloging standards, such as DCAT (Data Catalog Vocabulary), standardize metadata descriptions for datasets, enabling federated searches across portals; DCAT, developed under W3C and adopted in initiatives like the European Data Portal, uses RDF to describe dataset distributions, licenses, and access methods.[74] The FAIR principles—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—further guide format selection by requiring use of formal metadata vocabularies (e.g., Dublin Core or schema.org) and standardized protocols, ensuring data integrates across systems without custom mappings; interoperability in FAIR specifically mandates "use of formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation."[16] Open standards fall into categories like sharing vocabularies (e.g., SKOS for concepts), data exchange (e.g., CSV, JSON), and guidance documents, as classified by the Open Data Institute, to balance accessibility with advanced linking capabilities.[75]| Format | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications in Open Data |

|---|---|---|

| CSV | Plain text, delimiter-based rows | Tabular statistics, government reports[71] |

| JSON | Key-value pairs, nested objects | API endpoints, configuration files[72] |

| XML | Tagged elements, schema validation | Legacy documents, geospatial metadata[73] |

| RDF | Graph-based triples, URI identifiers | Linked datasets, semantic web integration[70] |

Platforms and Infrastructure

CKAN serves as a leading open-source data management system for constructing open data portals, enabling the publication, sharing, and discovery of datasets through features like metadata harvesting, API endpoints, user authentication, and extensible plugins. Developed under the stewardship of the Open Knowledge Foundation, it supports modular architecture for customization and integrates with standards such as Dublin Core and DCAT for interoperability.[76] As of 2025, CKAN powers portals hosting tens of thousands of datasets in national implementations, such as Canada's open.canada.ca, which aggregates data from federal agencies.[76] The U.S. federal portal data.gov exemplifies CKAN's application in large-scale infrastructure, launched in 2009 and aggregating datasets from over 100 agencies via automated harvesting and manual curation. It currently catalogs 364,170 datasets, spanning topics from health to geospatial information, with API access facilitating programmatic retrieval and integration into third-party applications.[77] Similarly, Australia's data.gov.au leverages CKAN to incorporate contributions from over 800 organizations, emphasizing federated data aggregation across government levels.[76] Alternative platforms include DKAN, an open-source Drupal-based system offering CKAN API compatibility for organizations reliant on content management systems, and GeoNode, a GIS-focused tool for spatial data infrastructures supporting map visualization and OGC standards compliance.[78] Commercial SaaS options, such as OpenDataSoft and Socrata (now integrated into broader enterprise suites), provide managed cloud hosting with built-in visualization dashboards, API management, and format support for CSV, JSON, and geospatial files, reducing self-hosting burdens for smaller entities.[78] These platforms typically deploy on cloud infrastructure like AWS or Azure for scalability, with self-hosted models requiring Linux servers and handling security via extensions, while SaaS variants outsource updates and compliance.[78] Infrastructure for open data platforms emphasizes decoupling storage from compute, often incorporating open table formats like Apache Iceberg for efficient querying across distributed systems, alongside metadata catalogs for governance.[79] Global adoption extends to initiatives like the European Data Portal, which federates national CKAN instances to provide unified access to over 1 million datasets as of 2023, promoting cross-border reuse through standardized APIs and bulk downloads. Such systems facilitate causal linkages in data pipelines, enabling empirical analysis without proprietary lock-in, though deployment success hinges on verifiable metadata quality to mitigate retrieval errors.[76]Implementation Strategies

Policy Mechanisms

Policy mechanisms for open data encompass legislative mandates, executive directives, and international guidelines that compel or incentivize governments and public institutions to release data in accessible, reusable formats. These instruments typically require machine-readable data publication, adherence to open licensing, and minimization of reuse restrictions, aiming to standardize practices across jurisdictions. For instance, policies often designate high-value datasets—such as geospatial, environmental, or statistical data—for priority release without charge or exclusivity.[28][80] In the United States, the OPEN Government Data Act, enacted on January 14, 2019, as part of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act, mandates federal agencies to publish non-sensitive data assets online in open, machine-readable formats with associated metadata cataloged on Data.gov.[81][82] The law excludes certain entities like the Government Accountability Office but establishes a government-wide framework, including the Chief Data Officers Council to oversee implementation and prioritize datasets based on public value and usability.[83] It builds on prior efforts, such as the 2012 Digital Government Strategy, which required agencies to identify and post three high-value datasets annually.[43] At the state level, policies vary; as of 2023, over 20 U.S. states had enacted open data laws or executive orders requiring portals for public data release in standardized formats like CSV or JSON.[84] The European Union's Open Data Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/1024), adopted on June 20, 2019, and fully transposed by member states by July 16, 2021, updates the 2003 Public Sector Information Directive to facilitate reuse of public sector data across borders.[27] It mandates that documents held by public sector bodies be made available for reuse under open licenses, with dynamic data provided via APIs where feasible, and prohibits exclusive arrangements that limit competition.[28] High-value datasets, identified in a 2023 Commission implementing act, must be released free of charge through centralized platforms like the European Data Portal, covering themes such as mobility, environment, and company registers to stimulate economic reuse.[28] Internationally, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides non-binding principles and benchmarks for open data policies, as outlined in its 2017 Recommendation of the Council on Enhancing Public Sector Access to Research Data and the OURdata Index.[85] The 2023 OURdata Index evaluates 40 countries on policy frameworks, including forward planning for data release and user engagement, with top performers like Korea and France scoring high due to comprehensive mandates integrating open data into national digital strategies.[80] These mechanisms often link data openness to broader open government commitments, such as those under the Open Government Partnership, which since 2011 has seen over 70 countries commit to specific open data action plans with verifiable milestones.[86] Empirical assessments, like OECD surveys, indicate that robust policies correlate with higher data reuse rates, though implementation gaps persist in resource-constrained settings.[80]Legal and Licensing Considerations