Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

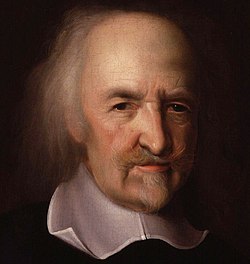

Thucydides

View on Wikipedia

Thucydides (/θjuːˈsɪdɪˌdiːz/ thew-SID-ih-deez; Ancient Greek: Θουκυδίδης, romanized: Thoukudídēs [tʰuːkydǐdɛːs]; c. 460 – c. 400 BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientific history" by those who accept his claims to have applied strict standards of impartiality and evidence-gathering and analysis of cause and effect, without reference to intervention by the gods, as outlined in his introduction to his work.[3][4][5]

Key Information

Thucydides has been called the father of the school of political realism, which views the political behavior of individuals and the subsequent outcomes of relations between states as ultimately mediated by, and constructed upon, fear and self-interest.[6] His text is still studied at universities and military colleges worldwide.[7] The Melian dialogue is regarded as a seminal text of international relations theory, while his version of Pericles's Funeral Oration is widely studied by political theorists, historians, and students of the classics. More generally, Thucydides developed an understanding of human nature to explain behavior in such crises as plagues, massacres, and wars.[8]

Life

[edit]In spite of his stature as a historian, modern historians know relatively little about Thucydides's life. The most reliable information comes from his own History of the Peloponnesian War, in which he mentions his nationality, paternity, and birthplace. Thucydides says that he fought in the war, contracted the plague, and was exiled by the democracy. He may have also been involved in quelling the Samian Revolt.[9]

Evidence from the classical period

[edit]Thucydides identifies himself as an Athenian, telling us that his father's name was Olorus and that he was from the Athenian deme of Halimous.[10] A disputed anecdote from his early life says that when Thucydides was 10–12 years old, he and his father were supposed to have gone to the agora of Athens where the young Thucydides heard a lecture by the historian Herodotus. According to some accounts, the young Thucydides wept with joy after hearing the lecture, deciding that writing history would be his life's calling. The same account also claims that after the lecture, Herodotus spoke with the youth and his father, stating: "Oloros your son yearns for knowledge." In all essence, the episode is most likely from a later Greek or Roman account of his life.[11] He survived the Plague of Athens,[12] which killed Pericles and many other Athenians. There is a first observation of acquired immunity.[13] He also records that he owned gold mines at Scapte Hyle (literally "Dug Woodland"), a coastal area in Thrace, opposite the island of Thasos.[14]

Because of his influence in the Thracian region, Thucydides wrote, he was sent as a strategos (general) to Thasos in 424 BC. During the winter of 424–423 BC, the Spartan general Brasidas attacked Amphipolis, a half-day's sail west from Thasos on the Thracian coast, sparking the Battle of Amphipolis. Eucles, the Athenian commander at Amphipolis, sent to Thucydides for help.[15] Brasidas, aware of the presence of Thucydides on Thasos and his influence with the people of Amphipolis, and afraid of help arriving by sea, acted quickly to offer moderate terms to the Amphipolitans for their surrender, which they accepted. Thus, when Thucydides arrived, Amphipolis was already under Spartan control.[16]

Amphipolis was of considerable strategic importance, and news of its fall caused great consternation in Athens.[17] It was blamed on Thucydides, although he claimed that it was not his fault and that he had simply been unable to reach it in time. Because of his failure to save Amphipolis, he was exiled:[18]

I lived through the whole of it, being of an age to comprehend events, and giving my attention to them in order to know the exact truth about them. It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly.

Using his status as an exile from Athens to travel freely among the Peloponnesian allies, he was able to view the war from the perspective of both sides. Thucydides claimed that he began writing his history as soon as the war broke out, because he thought it would be one of the greatest wars waged among the Greeks in terms of scale:

Thucydides, an Athenian, wrote the history of the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians, beginning at the moment that it broke out, and believing that it would be a great war, and more worthy of relation than any that had preceded it.[19]

This is all that Thucydides wrote about his own life, but a few other facts are available from reliable contemporary sources. Herodotus wrote that the name Olorus, Thucydides's father's name, was connected with Thrace and Thracian royalty.[20] Thucydides was probably connected through family to the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades and his son Cimon, leaders of the old aristocracy supplanted by the Radical Democrats. Cimon's maternal grandfather's name also was Olorus, making the connection quite likely. Another Thucydides lived before the historian and was also linked with Thrace, making a family connection between them very likely as well.

Combining all the fragmentary evidence available, it seems that his family had owned a large estate in Thrace, one that even contained gold mines, and which allowed the family considerable and lasting affluence. The security and continued prosperity of the wealthy estate must have necessitated formal ties with local kings or chieftains, which explains the adoption of the distinctly Thracian royal name Óloros into the family. Once exiled, Thucydides is commonly said to have taken up permanent residence in the estate and, given his ample income from the gold mines, he was able to dedicate himself to full-time history writing and research. In essence, he was a well-connected gentleman of considerable resources who, after involuntarily retiring from the political and military spheres, decided to fund his own historical investigations.

Later sources

[edit]The remaining evidence for Thucydides's life comes from later and rather less reliable ancient sources; Marcellinus wrote Thucydides's biography about a thousand years after his death. According to Pausanias, someone named Oenobius had a law passed allowing Thucydides to return to Athens, presumably shortly after the city's surrender and the end of the war in 404 BC. Pausanias goes on to say that Thucydides was murdered on his way back to Athens, placing his tomb near the Melite gate.[21] Many doubt this account, seeing evidence to suggest he lived as late as 397 BC, or perhaps slightly later. Plutarch preserves a tradition that he was murdered in Skaptē Hulē and that his remains were returned to Athens, where a monument to him was erected in Cimon's family plot.[22] There are problems with this, since this was outside Thucydides's deme and the tradition goes back to Polemon, who asserted he had discovered just such a memorial.[23] Didymus mentions another tomb in Thrace.[24]

Thucydides's narrative breaks off in the middle of the year 411 BC, and this abrupt end has traditionally been explained as due to his death while writing the book, although other explanations have been put forward.

During his description of the Athenian plague, he remarks that old Athenians seemed to remember a verse predicting a Dorian War that would bring about a "plague" (loimos) λοιμός.[25] A dispute later arose, when some claimed that the saying referred to the advent in such a war of "famine" or "starvation" (limos) λιμός. Thucydides draws the conclusion that people adapt their recollections to their present state of suffering. Were the same situation to recur, but with people experiencing famine rather than a pestilence, the verse would be remembered differently, in terms of starvation (limos), thereby cancelling the received adage about a plague (loimos).[26][27]

Thucydides admired Pericles, approving of his power over the people and showing a marked distaste for the demagogues who followed him. He did not approve of the democratic commoners nor of the radical democracy that Pericles ushered in, but considered democracy acceptable when guided by a good leader.[28] Thucydides's presentation of events is generally even-handed; for example, he does not minimize the negative effect of his own failure at Amphipolis. Occasionally, however, strong passions break through, as in his scathing appraisals of the democratic leaders Cleon[29][30] and Hyperbolus.[31] Sometimes, Cleon has been connected with Thucydides's exile.[32]

It has been argued that Thucydides was moved by the suffering inherent in war and concerned about the excesses to which human nature is prone in such circumstances, as in his analysis of the atrocities committed during the civil conflict on Corcyra,[33] which includes the phrase "war is a violent teacher" (πόλεμος βίαιος διδάσκαλος).

The History of the Peloponnesian War

[edit]

Thucydides believed that the Peloponnesian War represented an event of unmatched importance.[34] As such, he began to write the History at the onset of the war in 431 BC.[35][36] He declared his intention was to write an account which would serve as "a possession for all time".[37] The History breaks off near the end of the twenty-first year of the war (411 BC), in the wake of the Athenian defeat at Syracuse, and so does not elaborate on the final seven years of the conflict.

The History of the Peloponnesian War continued to be modified well beyond the end of the war in 404 BC, as exemplified by a reference at Book I.1.13[38] to the conclusion of the war.[39] After his death, Thucydides's History was subdivided into eight books: its modern title is the History of the Peloponnesian War. This subdivision was most likely made by librarians and archivists, themselves being historians and scholars, most likely working in the Library of Alexandria.[citation needed]

Thucydides is generally regarded as one of the first true historians. Like his predecessor Herodotus, known as "the father of history", Thucydides places a high value on eyewitness testimony and writes about events in which he probably took part. He also assiduously consulted written documents and interviewed participants about the events that he recorded. Unlike Herodotus, whose stories often teach that a hubris invites the wrath of the deities, Thucydides does not acknowledge divine intervention in human affairs.[40]

Thucydides exerted wide historiographical influence on subsequent Hellenistic and Roman historians, although the exact description of his style in relation to many successive historians remains unclear.[41] Readers in antiquity often placed the continuation of the stylistic legacy of the History in the writings of Thucydides's putative intellectual successor Xenophon. Such readings often described Xenophon's treatises as attempts to "finish" Thucydides's History. Many of these interpretations, however, have garnered significant scepticism among modern scholars, such as Dillery, who spurn the view of interpreting Xenophon qua Thucydides, arguing that the latter's "modern" history (defined as constructed based on literary and historical themes) is antithetical to the former's account in the Hellenica, which diverges from the Hellenic historiographical tradition in its absence of a preface or introduction to the text and the associated lack of an "overarching concept" unifying the history.[42]

A noteworthy difference between Thucydides's method of writing history and that of modern historians is Thucydides's inclusion of lengthy formal speeches that, as he states, were literary reconstructions rather than quotations of what was said—or, perhaps, what he believed ought to have been said. Arguably, had he not done this, the gist of what was said would not otherwise be known at all—whereas today there is a plethora of documentation—written records, archives, and recording technology for historians to consult. Therefore, Thucydides's method served to rescue his mostly oral sources from oblivion. We do not know how these historical figures spoke. Thucydides's recreation uses a heroic stylistic register. A celebrated example is Pericles' funeral oration, which heaps honour on the dead and includes a defence of democracy:

The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own land, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not on stone but in the hearts and minds of men. (2:43)

Stylistically, the placement of this passage also serves to heighten the contrast with the description of the plague in Athens immediately following it, which graphically emphasizes the horror of human mortality, thereby conveying a powerful sense of verisimilitude:

Though many lay unburied, birds and beasts would not touch them, or died after tasting them [...]. The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also in which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons who had died there, just as they were; for, as the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, became equally contemptuous of the property of and the dues to the deities. All the burial rites before in use were entirely upset, and they buried the bodies as best they could. Many from want of the proper appliances, through so many of their friends having died already, had recourse to the most shameless sepultures: sometimes getting the start of those who had raised a pile, they threw their own dead body upon the stranger's pyre and ignited it; sometimes they tossed the corpse which they were carrying on the top of another that was burning, and so went off. (2:52)

Thucydides omits discussion of the arts, literature, or the social milieu in which the events in his book take place and in which he grew up. He saw himself as recording an event, not a period, and went to considerable lengths to exclude what he deemed frivolous or extraneous.

Philosophical outlook and influences

[edit]Paul Shorey calls Thucydides "a cynic devoid of moral sensibility".[44] In addition, he notes that Thucydides conceived of human nature as strictly determined by one's physical and social environments, alongside basic desires.[45] Francis Cornford was more nuanced: Thucydides's political vision was informed by a tragic ethical vision, in which:

Man, isolated from, and opposed to, Nature, moves along a narrow path, unrelated to what lies beyond and lighted only by a few dim rays of human 'foresight'(γνώμη/gnome), or by the false, wandering fires of Hope. He bears within him, self-contained, his destiny in his own character: and this, with the purposes which arise out of it, shapes his course. That is all, in Thucydides' view, that we can say: except that, now and again, out of the surrounding darkness comes the blinding strokes of Fortune, unaccountable and unforeseen.'[46]

Thucydides's work indicates an influence from the teachings of the Sophists that contributes substantially to the thinking and character of his History.[47] Possible evidence includes his skeptical ideas concerning justice and morality.[48] There are also elements within the History—such as his views on nature revolving around the factual, empirical, and the non-anthropomorphic—which suggest that he was at least aware of the views of philosophers such as Anaxagoras and Democritus. There is also evidence of his knowledge concerning some of the corpus of Hippocratic medical writings.[49]

Thucydides was especially interested in the relationship between human intelligence and judgment,[50] fortune and necessity,[51] and the idea that history is too irrational and incalculable to predict.[52]

Critical interpretation

[edit]

Scholars traditionally viewed Thucydides as recognizing and teaching the lesson that democracies need leadership but that leadership can be dangerous to democracy. Leo Strauss (in The City and Man) locates the problem in the nature of Athenian democracy, about which, he argued, Thucydides was ambivalent. Thucydides's "wisdom was made possible" by the Periclean democracy, which had the effect of liberating individual daring, enterprise and questioning spirit; this liberation, by permitting the growth of limitless political ambition, led to imperialism and eventually, to civic strife.[53]

For Canadian historian Charles Norris Cochrane (1889–1945), Thucydides's fastidious devotion to observable phenomena, focus on cause and effect and strict exclusion of other factors anticipates twentieth-century scientific positivism. Cochrane, the son of a physician, speculated that Thucydides generally (and especially in describing the plague in Athens) was influenced by the methods and thinking of early medical writers such as Hippocrates of Kos.[3]

After World War II, classical scholar Jacqueline de Romilly pointed out that the problem of Athenian imperialism was one of Thucydides's preoccupations and situated his history in the context of Greek thinking about international politics. Since the appearance of her study, other scholars further examined Thucydides's treatment of realpolitik.[citation needed]

Other scholars have brought to the fore the literary qualities of the History, which they see in the narrative tradition of Homer and Hesiod and as concerned with the concepts of justice and suffering found in Plato and Aristotle and questioned in Aeschylus and Sophocles.[54] Richard Ned Lebow terms Thucydides "the last of the tragedians", stating that "Thucydides drew heavily on epic poetry and tragedy to construct his history, which not surprisingly is also constructed as a narrative".[55] In this view, the blind and immoderate behaviour of the Athenians (and indeed of all the other actors)—although perhaps intrinsic to human nature—leads to their downfall. Thus his History could serve as a warning to leaders to be more prudent, by putting them on notice that someone would be scrutinizing their actions with a historian's objectivity rather than a chronicler's flattery.[56]

The historian J. B. Bury writes that the work of Thucydides "marks the longest and most decisive step that has ever been taken by a single man towards making history what it is today".[57]

Historian H. D. Kitto feels that Thucydides wrote about the Peloponnesian War, not because it was the most significant war in antiquity but because it caused the most suffering. Several passages of Thucydides's book are written "with an intensity of feeling hardly exceeded by Sappho herself".[58]

In his book The Open Society and Its Enemies, Karl Popper writes that Thucydides was the "greatest historian, perhaps, who ever lived". Thucydides's work, Popper goes on to say, represents "an interpretation, a point of view; and in this we need not agree with him". In the war between Athenian democracy and the "arrested oligarchic tribalism of Sparta", we must never forget Thucydides's "involuntary bias", and that "his heart was not with Athens, his native city."

Although he apparently did not belong to the extreme wing of the Athenian oligarchic clubs who conspired throughout the war with the enemy, he was certainly a member of the oligarchic party, and a friend neither of the Athenian people, the demos, who had exiled him, nor of its imperialist policy.[59]

Comparison with Herodotus

[edit]

Thucydides and his immediate predecessor, Herodotus, both exerted a significant influence on Western historiography. Thucydides does not mention his counterpart by name, but his famous introductory statement is thought to refer to him:[60][61]

To hear this history rehearsed, for that there be inserted in it no fables, shall be perhaps not delightful. But he that desires to look into the truth of things done, and which (according to the condition of humanity) may be done again, or at least their like, shall find enough herein to make him think it profitable. And it is compiled rather for an everlasting possession than to be rehearsed for a prize. (1:22)

Herodotus records in his Histories not only the events of the Persian Wars, but also geographical and ethnographical information, as well as the fables related to him during his extensive travels. Typically, he passes no definitive judgment on what he has heard. In the case of conflicting or unlikely accounts, he presents both sides, says what he believes and then invites readers to decide for themselves.[62] Of course, modern historians would generally leave out their personal beliefs, which is a form of passing judgment upon the events and people about which the historian is reporting. The work of Herodotus is reported to have been recited at festivals, where prizes were awarded, as for example, during the games at Olympia.[63]

Herodotus views history as a source of moral lessons, with conflicts and wars as misfortunes flowing from initial acts of injustice perpetuated through cycles of revenge.[64] In contrast, Thucydides claims to confine himself to factual reports of contemporary political and military events, based on unambiguous, first-hand, eye-witness accounts,[65] although, unlike Herodotus, he does not reveal his sources. Thucydides views life exclusively as political life, and history in terms of political history. Conventional moral considerations play no role in his analysis of political events while geographic and ethnographic aspects are omitted or, at best, of secondary importance. Subsequent Greek historians—such as Ctesias, Diodorus, Strabo, Polybius and Plutarch—held up Thucydides's writings as a model of truthful history. Lucian[66] refers to Thucydides as having given Greek historians their law, requiring them to say what had been done (ὡς ἐπράχθη). Greek historians of the fourth century BC accepted that history was political and that contemporary history was the proper domain of a historian.[67] Cicero calls Herodotus the "father of history";[68] yet the Greek writer Plutarch, in his Moralia (Ethics) denigrated Herodotus, notably calling him a philobarbaros, a "barbarian lover", to the detriment of the Greeks.[69] Unlike Thucydides, however, these authors all continued to view history as a source of moral lessons, thereby infusing their works with personal biases generally missing from Thucydides's clear-eyed, non-judgmental writings focused on reporting events in a non-biased manner.[citation needed]

Due to the loss of the ability to read Greek, Thucydides and Herodotus were largely forgotten during the Middle Ages in Western Europe, although their influence continued in the Byzantine world. In Europe, Herodotus become known and highly respected only in the late-sixteenth and early-seventeenth century as an ethnographer, in part due to the discovery of America, where customs and animals were encountered that were even more surprising than what he had related. During the Reformation, moreover, information about Middle Eastern countries in the Histories provided a basis for establishing Biblical chronology as advocated by Isaac Newton.

The first European translation of Thucydides (into Latin) was made by the humanist Lorenzo Valla between 1448 and 1452, and the first Greek edition was published by Aldo Manuzio in 1502. During the Renaissance, however, Thucydides attracted less interest among Western European historians as a political philosopher than his successor, Polybius,[70] although Poggio Bracciolini claimed to have been influenced by him. There is not much evidence of Thucydides's influence in Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince (1513), which held that the chief aim of a new prince must be to "maintain his state" [i.e., his power] and that in so doing he is often compelled to act against faith, humanity, and religion. Later historians, such as J. B. Bury, however, have noted parallels between them:

If, instead of a history, Thucydides had written an analytical treatise on politics, with particular reference to the Athenian empire, it is probable that ... he could have forestalled Machiavelli ... [since] the whole innuendo of the Thucydidean treatment of history agrees with the fundamental postulate of Machiavelli, the supremacy of reason of state. To maintain a state, said the Florentine thinker, "a statesman is often compelled to act against faith, humanity and religion". ... But ... the true Machiavelli, not the Machiavelli of fable ... entertained an ideal: Italy for the Italians, Italy freed from the stranger: and in the service of this ideal he desired to see his speculative science of politics applied. Thucydides has no political aim in view: he was purely a historian. But it was part of the method of both alike to eliminate conventional sentiment and morality.[71]

In the seventeenth century, the English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose Leviathan advocated absolute monarchy, admired Thucydides and in 1628 was the first to translate his writings into English directly from Greek. Thucydides, Hobbes, and Machiavelli are together considered the founding fathers of western political realism, according to which, state policy must primarily or solely focus on the need to maintain military and economic power rather than on ideals or ethics.

Nineteenth-century positivist historians stressed what they saw as Thucydides's seriousness, his scientific objectivity and his advanced handling of evidence. A virtual cult following developed among such German philosophers as Friedrich Schelling, Friedrich Schlegel, and Friedrich Nietzsche, who claimed that, "[in Thucydides], the portrayer of Man, that culture of the most impartial knowledge of the world finds its last glorious flower." The late-eighteenth-century Swiss historian Johannes von Müller described Thucydides as "the favourite author of the greatest and noblest men, and one of the best teachers of the wisdom of human life".[72] For Eduard Meyer, Thomas Babington Macaulay and Leopold von Ranke, who initiated modern source-based history writing,[73] Thucydides was again the model historian.[74][75]

Generals and statesmen loved him: the world he drew was theirs, an exclusive power-brokers' club. It is no accident that even today Thucydides turns up as a guiding spirit in military academies, neocon think tanks and the writings of men like Henry Kissinger; whereas Herodotus has been the choice of imaginative novelists (Michael Ondaatje's novel The English Patient and the film based on it boosted the sale of the Histories to a wholly unforeseen degree) and—as food for a starved soul—of an equally imaginative foreign correspondent from Iron Curtain Poland, Ryszard Kapuscinski.[76]

These historians also admired Herodotus, however, as social and ethnographic history increasingly came to be recognized as complementary to political history.[77] In the twentieth century, this trend gave rise to the works of Johan Huizinga, Marc Bloch, and Fernand Braudel, who pioneered the study of long-term cultural and economic developments and the patterns of everyday life. The Annales School, which exemplifies this direction, has been viewed as extending the tradition of Herodotus.[78]

At the same time, Thucydides's influence was increasingly important in the area of international relations during the Cold War, through the work of Hans Morgenthau, Leo Strauss,[79] and Edward Carr.[80]

The tension between the Thucydidean and Herodotean traditions extends beyond historical research. According to Irving Kristol, self-described founder of American neoconservatism, Thucydides wrote "the favorite neoconservative text on foreign affairs";[81] and Thucydides is a required text at the Naval War College, an American institution located in Rhode Island. On the other hand, Daniel Mendelsohn, in a review of a recent edition of Herodotus, suggests that, at least in his graduate school days during the Cold War, professing admiration of Thucydides served as a form of self-presentation:

To be an admirer of Thucydides' History, with its deep cynicism about political, rhetorical and ideological hypocrisy, with its all too recognizable protagonists—a liberal yet imperialistic democracy and an authoritarian oligarchy, engaged in a war of attrition fought by proxy at the remote fringes of empire—was to advertise yourself as a hardheaded connoisseur of global Realpolitik.[82]

Another contemporary historian believes that, while it is true that critical history "began with Thucydides, one may also argue that Herodotus' looking at the past as a reason why the present is the way it is, and to search for causality for events beyond the realms of Tyche and the Gods, was a much larger step."[83]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Virginia J. Hunter,Past and Process in Herodotus and Thucydides, (Princeton University Press, 2017), 4.

- ^ Luciano Canfora, 'Biographical Obscurities and Problems of Composition', in Antonis Tsakmakis, Antonios Rengakos (eds.), Brill's Companion to Thucydides, Brill, 2006 ISBN 978-9-047-40484-2, pp. 3–31.

- ^ a b Cochrane, Charles Norris (1929). Thucydides and the Science of History. Oxford University Press. p. 179.

- ^ Meyer, p. 67; de Sainte Croix.

- ^ Korab-Karpowicz, W. Julian (26 July 2010). "Political Realism in International Relations". In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 ed.). Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ Strauss, p. 139.

- ^ Harloe, Katherine, Morley, Neville, eds., Thucydides and the Modern World: Reception, Reinterpretation, and Influence from the Renaissance to the Present. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press (2012). p. 12

- ^ "What Thucydides Teaches Us About War, Politics, and the Human Condition". War on the Rocks. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War 1.117

- ^ Thucydides 4.104

- ^ Herodot iz Halikarnasa. Zgodbe. Ljubljana: Slovenska Matica v Ljubljani (2003), p. 22. The original quote (in Slovene): Oloros, tvoj sin koprni po izobrazbi.

- ^ Thucydides 2.48.1–3

- ^ Thucydides 2.51.6

- ^ Thucydides 4.105.1

- ^ Thucydides 4.104.1

- ^ Thucydides 4.105–106.3

- ^ Thucydides 4.108.1–7

- ^ Thucydides 5.26.5

- ^ "Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, book 1, chapter 1, section 1". data.perseus.org. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ 6.39.1

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 1.23.9

- ^ Plutarch, Cimon 4.1.2

- ^ Luciano Canfora( 2006). “Biographical Obscurities and Problems of Composition” Antonis Tsakmakis, Antonios Rengakos (eds.). Brill's Companion to Thucydides Brill, ISBN 978-90-474-0484-2 pp. 6–7, 63–33

- ^ Canfora (2006). p. 8

- ^ “ἥξει Δωριακὸς πόλεμος καὶ λοιμὸς ἅμ᾽ αὐτῷ.’ 2:54.2

- ^ Thucydides, Peloponessian War, 2:54:2-3

- ^ Lowell Edmunds, 'Thucydides in the Act of Writing,' in Jeffrey S. Rusten (ed.), Thucydides, Oxford University Press 2009 ISBN 978-0-199-20619-3 pp.91–113, p.111

- ^ Thucydides 2.65.1

- ^ Thucydides 3.36.6

- ^ Thucydides 4.27, 5.16.1

- ^ Thucydides 8.73.3

- ^ Marcellinus, Life of Thucydides 46

- ^ Thucydides 3.82–83

- ^ Thucydides 1.1.1

- ^ Thucydides 1.1

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 9

- ^ Thucydides 1.22.4

- ^ Thucydides. . History of the Peloponnesian War – via Wikisource.

- ^ Mynott, Jeremy, The War of the Peloponnesians and Athenians. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press (2013). p. 11

- ^ Grant, Michael (1995). Greek and Roman Historians: Information and Misinformation. London: Routledge. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0-415-11770-4.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon, Spawforth, Antony, Eidinow, Esther, The Oxford Classical Dictionary. New York, Oxford University Press (2012). pp. 692–693

- ^ Dillery, John, Xenophon and the History of His Times. London, Routledge (2002).

- ^ "Pericles' Funeral Oration". the-athenaeum.org. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 144.

Endnote cites: Paul Shorey, “On the Implicit Ethics and Psychology of Thucydides” - ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 144.

- ^ Benjamin Earley, The Thucydidean Turn: (Re)Interpreting Thucydides' Political Thought Before, During and After the Great War, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020 ISBN 978-1-350-12372-4 pp. 40–43 [41], citing F. M. Cornford Cornford, Thucidides Mythistoricus, (1907) Routledge 2014 ISBN 978-1-317-68751-1 pp. 69–70.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 22

The page itself refers to an endnote detailing that this conclusion is inspired by multiple works, including but not limited to: Athens as A Cultural Center by Martin Ostwald; Thucydides by John H. Finley; Intellectual Experiments of Greek Enlightenment by Friedrich Solmsen - ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 152.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 147.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 156.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 157.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez. Thucydides. (Princeton University Press, 2015), p. 160.

- ^ Russett, p. 45.

- ^ Clifford Orwin, The Humanity of Thucydides, Princeton, 1994.

- ^ Richard Ned Lebow, The Tragic vision of Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 20.

- ^ See also Walter Robert Connor, Thucydides (Princeton University Press, 1987).

- ^ Bury, J. B. (1958). The Ancient Greek Historians. New York: Dover Publications. p. 147.

- ^ Bowker, Stan (1966). "Kitto At BC". The Heights. XLVI (16).

- ^ Popper, Karl Raimund (2013). The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-691-15813-6.

- ^ Lucian, How to write history, p. 42

- ^ Thucydides 1.22

- ^ Momigliano, pp. 39, 40.

- ^ Lucian: Herodotus, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Ryszard Kapuscinski: Travels with Herodotus, p. 78.

- ^ Thucydides 1.23

- ^ Lucian, pp. 25, 41.

- ^ Momigliano, Ch. 2, IV.

- ^ Cicero, Laws 1.5.

- ^ Plutarch, On the Malignity of Herodotus, Moralia XI (Loeb Classical Library 426).

- ^ Momigliano Chapter 2, V.

- ^ J. B. Bury, The Ancient Greek Historians (London, MacMillan, 1909), pp. 140–143.

- ^ Johannes von Müller, The History of the World (Boston: Thomas H. Webb and Co., 1842), Vol. 1, p. 61.

- ^ See Anthony Grafton, The Footnote, a Curious History (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1999)

- ^ Momigliano, p. 50.

- ^ For his part, Peter Green notes of these historians, the fact "That [Thucydides] was exiled for military incompetence, did a hatchet job on the man responsible and praised as virtually unbeatable the Spartan general to whom he had lost the key city of Amphipolis bothered them not at all." Peter Green (2008) cit.

- ^ (Green 2008, op. cit.)

- ^ Momigliano, p. 52.

- ^ Stuart Clark (ed.): The Annales school: critical assessments, Vol. II, 1999.

- ^ See essay on Thucydides in The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism: An Introduction to the Thought of Leo Strauss – Essays and Lectures by Leo Strauss, edited by Thomas L. Pangle (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

- ^ See, for example, E. H. Carr's The Twenty Years' Crisis.

- ^ "The Neoconservative Persuasion". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 16 August 2003.

- ^ "Arms and the Man: What was Herodotus trying to tell us?" (The New Yorker, April 28, 2008)

- ^ Sorensen, Benjamin (2013). "The Legacy of J. B. Bury, 'Progressive' Historian of Ancient Greece". Saber and Scroll. 2 (2).

References and further reading

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Herodot iz Halikarnasa. Zgodbe. Ljubljana: Slovenska Matica v Ljubljani (2003).

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. London, J. M. Dent; New York, E. P. Dutton (1910). . The classic translation by Richard Crawley. Reissued by the Echo Library in 2006. ISBN 1-4068-0984-5 OCLC 173484508

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. Indianapolis, Hackett (1998); translation by Steven Lattimore. ISBN 978-0-87220-394-5.

- Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1920). ISBN 0-674-99133-8 perseus.tufts.edu.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, Books I-II, (Loeb Classical Library) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918). ISBN 0-674-99104-4. perseus.tufts.edu.

- Plutarch, Lives, Bernadotte Perrin (translator), Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. (1914). ISBN 0-674-99053-6 perseus.tufts.edu.

- The Landmark Thucydides, Edited by Robert B. Strassler, Richard Crawley translation, Annotated, Indexed and Illustrated, A Touchstone Book, New York, 1996 ISBN 0-684-82815-4

- * Thucydidis Historiae, 3 vols., ed. Ioannes Baptista Alberti, Rome, Typis Officinae polygraphicae, 1972–2000 (a standard text edition).

Secondary sources

[edit]- Cornelius Castoriadis, "The Greek Polis and the Creation of Democracy" in The Castoriadis Reader. Translated and edited by David Ames Curtis, Blackwell Publishers Ltd 1997, pp. 267–289 [Cornelius Castoriadis, "La polis grecque et la création de la démocratie" in Domaines de l’homme. Les Carrefours du labyrinthe II. Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1986, pp. 261–306].

- Cornelius Castoriadis, Thucydide, la force et le droit. Ce qui fait la Grèce. Tome 3, Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2011.

- Connor, W. Robert, Thucydides. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-691-03569-5.

- Dewald, Carolyn, Thucydides' War Narrative: A Structural Study. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-24127-4).

- Finley, John Huston Jr., Thucydides. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1947.

- Forde, Steven, The ambition to rule: Alcibiades and the politics of imperialism in Thucydides. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-8014-2138-1.

- Hanson, Victor Davis, A War Like No Other: How the Athenians and Spartans Fought the Peloponnesian War. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-6095-8.

- Hornblower, Simon, A Commentary on Thucydides. 2 vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991–1996. ISBN 0-19-815099-7 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-19-927625-0 (vol. 2).

- Hornblower, Simon, Thucydides. London: Duckworth, 1987. ISBN 0-7156-2156-4.

- Kagan, Donald, The Archidamian War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974. ISBN 0-8014-0889-X OCLC 1129967.

- Kagan, Donald, The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking Press, 2003. ISBN 0-670-03211-5.

- Kelly, Paul, "Thucydides: The naturalness of war" in Conflict, War and Revolution: The problem of politics in international political thought. London: LSE Press, 2022. ISBN 978-1-909890-73-2

- Luce, T. J., The Greek Historians. London: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0-415-10593-5.

- Luginbill, R. D., Thucydides on War and National Character. Boulder: Westview, 1999. ISBN 0-8133-3644-9.

- Momigliano, Arnaldo, The Classical Foundations of Modern Historiography (= Sather Classical Lectures 54). Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Novo, Andrew and Jay Parker, Restoring Thucydides. New York: Cambria Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1621964742.

- Orwin, Clifford, The Humanity of Thucydides. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-691-03449-4.

- Podoksik, Efraim, "Justice, Power, and Athenian Imperialism: An Ideological Moment in Thucydides' History" in History of Political Thought 26(1): 21–42, 2005.

- Romilly, Jacqueline de, Thucydides and Athenian Imperialism. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1963. ISBN 0-88143-072-2.

- Rood, Tim, Thucydides: Narrative and Explanation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-927585-8.

- Russett, Bruce (1993). Grasping the Democratic Peace. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03346-3.

- de Sainte Croix, The origins of the Peloponnesian War. London: Duckworth, 1972. pp. xii, 444.

- Strassler, Robert B, ed, The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian War. New York: Free Press, 1996. ISBN 0-684-82815-4.

- Strauss, Leo, The City and Man Chicago: Rand McNally, 1964.

- Zagorin, Perez, Thucydides: an Introduction for the Common Reader. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-691-13880-X OCLC 57010364.

External links

[edit]- Works by Thucydides at Perseus Digital Library

- Works by Thucydides in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Thucydides at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thucydides at the Internet Archive

- Works by Thucydides at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Jebb, Richard Claverhouse; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). pp. 893–896.

- Short Bibliography on Thucydides Lowell Edmunds, Rutgers University

- Thomas Hobbes' Translation of Thucydides

- Anthony Grafton, "Did Thucydides Really Tell the Truth?" in Slate, October 2009.

- Bibliography at GreatThinkers.org

- Works by Thucydides at Somni:

- Thucididis Historiarum liber a Laurentio Vallensi traductus. Italy, 1450–1499.

- De bello Peloponnesiaco. Naples, 1475.