Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

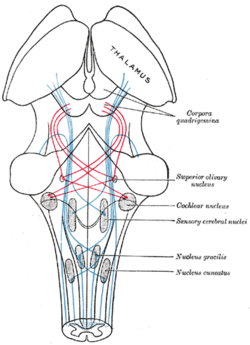

Superior olivary complex

View on Wikipedia| Superior olivary complex | |

|---|---|

Scheme showing the course of the fibers of the lemniscus; medial lemniscus in blue, lateral in red. (Superior olivary nucleus is labeled at center right.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nucleus olivaris superior |

| MeSH | D065832 |

| NeuroNames | 569 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1307 |

| TA98 | A14.1.05.415 |

| TA2 | 5937 |

| FMA | 72247 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The superior olivary complex (SOC) or superior olive is a collection of brainstem nuclei that is located in pons, functions in multiple aspects of hearing and is an important component of the ascending and descending auditory pathways of the auditory system. The SOC is intimately related to the trapezoid body: most of the cell groups of the SOC are dorsal (posterior in primates) to this axon bundle while a number of cell groups are embedded in the trapezoid body. Overall, the SOC displays a significant interspecies variation, being largest in bats and rodents and smaller in primates.

Physiology

[edit]The superior olivary nucleus plays a number of roles in hearing. The medial superior olive (MSO) is a specialized nucleus that is believed to measure the time difference of arrival of sounds between the ears (the interaural time difference or ITD). The ITD is a major cue for determining the azimuth of sounds, i.e., localising them on the azimuthal plane – their degree to the left or the right.

The lateral superior olive (LSO) is believed to be involved in measuring the difference in sound intensity between the ears (the interaural level difference or ILD). The ILD is a second major cue in determining the azimuth of high-frequency sounds.

Relationship to auditory system

[edit]The superior olivary complex is generally located in the pons, but in humans extends from the rostral medulla to the mid-pons[1] and receives projections predominantly from the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) via the trapezoid body, although the posteroventral nucleus projects to the SOC via the intermediate acoustic stria. The SOC is the first major site of convergence of auditory information from the left and right ears.[2]

Primary nuclei

[edit]The superior olivary complex is divided into three primary nuclei, the MSO, LSO, and the Medial nucleus of the trapezoid body, and several smaller periolivary nuclei.[3] These three nuclei are the most studied, and therefore best understood. Typically, they are regarded as forming the ascending azimuthal localization pathway.

Medial superior olive (MSO)

[edit]The medial superior olive is thought to help locate the azimuth of a sound, that is, the angle to the left or right where the sound source is located. Sound elevation cues are not processed in the olivary complex. The fusiform cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), which are thought to contribute to localization in elevation, bypass the SOC and project directly to the inferior colliculus. Only horizontal data is present, but it does come from two different ear sources, which aids in the localizing of sound on the azimuth axis.[4] The way in which the superior olive does this is by measuring the differences in time between two ear signals recording the same stimulus. Traveling around the head takes about 700 μs, and the medial superior olive is able to distinguish time differences much smaller than this. In fact, it is observed that people can detect interaural differences down to 10 μs.[4] The nucleus is tonotopically organized, but the azimuthal receptive field projection is "most likely a complex, nonlinear map".[5]

The projections of the medial superior olive terminate densely in the ipsilateral central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (CNIC). The majority of these axons are considered to be "round shaped" or type R. These R axons are mostly glutamatergic and contain round synaptic vesicles and form asymmetric synaptic junctions.[2]

- This is the largest of the nuclei and in humans it contains approximately 15,500 neurons.[1]

- Each MSO receives bilateral inputs from the right and left AVCNs.

- The output is via the ipsilateral lateral lemniscus to the inferior colliculus.[6]

- The MSO responds better to binaural stimuli.

- The MSO's main function is detection of interaural time difference (ITD) cues to binaural lateralization.

- The MSO is severely disrupted in the autistic brain.[7]

Lateral superior olive (LSO)

[edit]This olive has similar functions to the medial superior olive, but employs intensity to localize the sound source.[8] The LSO receives excitatory, glutamatergic input from spherical bushy cells in the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus and inhibitory, glycinergic input from the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB). The MNTB is driven by excitatory input from globular bushy cells in the contralateral cochlear nucleus. Thus, the LSO receives excitatory input from the ipsilateral ear and inhibitory input from the contralateral ear. This is the basis of ILD sensitivity. Projections from both cochlear nuclei are primarily high frequency, and these frequencies are subsequently represented by the majority of LSO neurons (>2/3 over 2–3 kHz in cat). The LSO does in fact encode frequency across the animals audible range (not just "high" frequency). Additional inputs derive from the ipsilateral LNTB (glycinergic, see below), which provide inhibitory information from the ipsilateral cochlear nucleus.[9] Another possibly inhibitory input derives from ipsilateral AVCN non-spherical cells. These cells are either globular bushy or multipolar (stellate). Either of these two inputs could provide the basis for ipsilateral inhibition seen in response maps flanking the primary excitation, sharpening the unit's frequency tuning.[10][11]

The LSO projects bilaterally to the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus (ICC). Ipsilateral projections are primarily inhibitory (glycinergic), and the contralateral projections are excitatory. Additional projection targets include the dorsal and ventral nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (DNLL & VNLL). The GABAergic projections from the DNLL form a major source of GABA in the auditory brainstem, and project bilaterally to the ICC and to the contralateral DNLL. These converging excitatory and inhibitory connections may act to decrease the level dependence of ILD sensitivity in the ICC compared to the LSO.

Additional projections form the lateral olivocochlear bundle (LOC), which innervates cochlear inner hair cells. These projections are thought to have a long time constant, and act to normalize the sound level detected by each ear in order to aid in sound localization.[12] Considerable species differences exist: LOC projection neurons are distributed within the LSO in rodents, and surround the LSO in predators (i.e. cat).

Medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB)

[edit]- The MNTB, in the trapezoid body, is composed of mainly neurons with round cell bodies which utilize glycine as a neurotransmitter.

- The size of the MNTB is reduced in primates.[13][14][15]

- Each MNTB neuron receives a large "calyx" type ending, the calyx of Held arising from the globular bushy cells in the contralateral AVCN.

- There are two response types found: a 'chopper type' similar to spindle cells in the AVCN and a primary type which is similar to those of bushy cells in the AVCN.

Periolivary nuclei

[edit]The SOC is composed of between six and nine periolivary nuclei, depending upon the researcher cited, typically named based upon their location with regard to the primary nuclei. These nuclei surround each of the primary nuclei, and contribute to both the ascending and descending auditory systems. These nuclei also form the source of the olivocochlear bundle, which innervates the cochlea.[16] In the guinea pig, ascending projections to the inferior colliculi are primarily ipsilateral (>80%), with the largest single source coming from the SPON. Also, ventral nuclei (RPO, VMPO, AVPO, & VNTB) are almost entirely ipsilateral, while the remaining nuclei project bilaterally.[17]

| Name | Cat | Guinea Pig | Rat | Mouse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSO | X | X | X | X |

| MSO | X | X | X | X* |

| MNTB | X | X | X | X |

| LNTB | X | X | "LVPO" | X |

| ALPO | X | X | ||

| PVPO | X | X | ||

| PPO | X | X | "CPO" | |

| VLPO | X | |||

| DPO | X | X | X | |

| DLPO | X | X | ||

| VTB | X | X | "MVPO" | X |

| AVPO | X | |||

| VMPO | X | X | ||

| RPO | X | X | ||

| SPN | "DMPO" | X | X | X |

,[17] *The MSO appears to be smaller and disorganized in mice.[18]

Ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body (VNTB)

[edit]- The VNTB is a small nucleus located laterally to the MNTB, and ventral to the MSO.[19]

- Made up of a heterogeneous population of cells, this nucleus projects to many auditory nuclei, and forms the medial olivocochlear bundle (MOC) which innervates cochlear outer hair cells.[20] These cells contain electromotile fibers, and act as mechanical amplifiers/attenuators within the cochlea.

- The nucleus projects to both IC, with no cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

- The VNTB also innervates the cochlear nuclei bilaterally, but mainly on the contralateral side.[20][22][23]

Lateral nucleus of the trapezoid body (LNTB)

[edit]- Located ventral to the LSO[19]

- AVCN spherical bushy cells project collaterals bilaterally, and globular bushy cells project collaterals ipsilaterally to LNTB neurons.[24]

- Cells are immunoreactive for glycine,[25] and are retrogradely labeled following injection of tritiated glycine into the LSO[9]

- The nucleus projects to both IC, with few cells projecting bilaterally,[21] as well as the ipsilateral LSO.[9]

- Large multipolar cells project to the cochlear nucleus, but not the IC, in both cat and guinea pig.[21][26]

- Inputs are often via end-bulbs of Held, producing very fast signal transduction.

Superior periolivary nucleus (SPON) (dorsomedial periolivary nucleus (DMPO))

[edit]- Located directly dorsal to the MNTB[19]

- In rats, SPON is a homogeneous GABAergic nucleus. These tonotopically organized neurons receive excitatory inputs from octopus and multipolar cells in the contralateral ventral cochlear nucleus,[27] a glycinergic (inhibitory) input from the ipsilateral MNTB, an unknown GABAergic (inhibitory) input, and project to the ipsilateral ICC.[28] Most neurons respond only at the offset of a stimulus, can phase lock to AM stimuli up to 200 Hz, and may form the basis for ICC duration selectivity.[29] Notably, SPON neurons do not receive descending inputs from the IC, and it does not project to the cochlea or cochlear nucleus as many periolivary nuclei do.[30]

- In contrast, glycinergic projections to ipsilateral ICC are observed in guinea pigs and chinchillas, suggesting a species-related neurotransmitter difference.[31]

- In guinea pigs, round to oval multipolar cells project to both IC, with many cells projecting bilaterally. The more elongated cells that project to the cochlear nucleus to not project to the ICC. There appear to be to populations of cells, one that projects ipsilaterally, and one that projects bilaterally.[21]

- The majority of information had come from rodent SPON, due to the nucleus' prominent size in these species, with very few studies have been done in cat DMPO,[32] none of which were extensive.

Dorsal periolivary nucleus (DPO)

[edit]- Located dorsal and medial to the LSO[19]

- Contains both EE (excited by both ears) and E0 (excited by the contralateral ear only) units.[33]

- Neurons are tonotopically organized, and high frequency.

- May belong to a single nucleus along with the DLPO[34]

- The nucleus projects to both IC, with no cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

Dorsolateral periolivary nucleus (DLPO)

[edit]- Located dorsal and lateral to the LSO[19]

- Contains both EE (excited by both ears) and E0 (excited by the contralateral ear only) units.

- Neurons are tonotopically organized, and low frequency.

- May belong to a single nucleus along with the DPO

- The nucleus projects to both IC, with few cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

Ventrolateral periolivary nucleus (VLPO)

[edit]- Located ventral to and within the ventral hillus of the LSO[19]

- Contains both EI (excited by contralateral and inhibited by ipsilateral ear) and E0 (excited by the contralateral ear only) units.

- Neurons are tonotopically organized, and high frequency.

- Subdivided into the LNTB, PPO and ALPO [35]

Anterolateral periolivary nucleus (ALPO)

[edit]- The nucleus projects to both IC, with no cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

- Large multipolar cells project to the cochlear nucleus, but not the IC, in both cat and guinea pig.[21][26]

Ventromedial periolivary nucleus (VMPO)

[edit]- Located between the MSO and MNTB.[19]

- Sends projections to the ICC bilaterally.[21]

- The nucleus projects to both IC, with no cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

Rostral periolivary nucleus (RPO) (anterior periolivary nucleus (APO))

[edit]- Located between the rostral pole of the MSO and the VNLL[19]

- Sometimes called the Ventral Nucleus of the Trapezoid Body (VNTB)[19]

Caudal periolivary nucleus (CPO) (posterior periolivary nucleus (PPO))

[edit]- Located between the caudal pole of the MSO and the facial nucleus (7N)[19]

Posteroventral periolivary nucleus (PVPO)

[edit]- The nucleus projects to both IC, with no cells projecting bilaterally.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 787 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 787 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b Kulesza RJ (March 2007). "Cytoarchitecture of the human superior olivary complex: medial and lateral superior olive". Hearing Research. 225 (1–2): 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2006.12.006. PMID 17250984. S2CID 19696622.

- ^ a b Oliver DL, Beckius GE, Shneiderman A (September 1995). "Axonal projections from the lateral and medial superior olive to the inferior colliculus of the cat: a study using electron microscopic autoradiography". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 360 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1002/cne.903600103. PMID 7499562. S2CID 22997698.

- ^ Cajal, S. R. Y. and L. Azoulay (1909). Histologie du système nerveux de l'homme et des vertébrés. Paris, Maloine.

- ^ a b Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessell TM (2000). Principles of neural science. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 591–624. ISBN 978-0-8385-7701-1. OCLC 249318861.

- ^ Oliver DL, Beckius GE, Bishop DC, Loftus WC, Batra R (August 2003). "Topography of interaural temporal disparity coding in projections of medial superior olive to inferior colliculus". The Journal of Neuroscience. 23 (19): 7438–7449. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07438.2003. PMC 6740450. PMID 12917380.

- ^ Rincón, Héctor; Gómez-Martínez, Mario; Gómez-Álvarez, Marcelo; Saldaña, Enrique (August 2024). "Medial superior olive in the rat: Anatomy, sources of input and axonal projections". Hearing Research. 449 109036. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2024.109036. ISSN 0378-5955. PMID 38797037.

- ^ Kulesza RJ, Lukose R, Stevens LV (January 2011). "Malformation of the human superior olive in autistic spectrum disorders". Brain Research. 1367: 360–371. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.015. PMID 20946889. S2CID 39753895.

- ^ Tsuchitani C, Boudreau JC (October 1967). "Encoding of stimulus frequency and intensity by cat superior olive S-segment cells". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 42 (4): 794–805. Bibcode:1967ASAJ...42..794T. doi:10.1121/1.1910651. PMID 6075565.

- ^ a b c Glendenning KK, Masterton RB, Baker BN, Wenthold RJ (August 1991). "Acoustic chiasm. III: Nature, distribution, and sources of afferents to the lateral superior olive in the cat". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 310 (3): 377–400. doi:10.1002/cne.903100308. PMID 1723989. S2CID 41964072.

- ^ Wu SH, Kelly JB (February 1994). "Physiological evidence for ipsilateral inhibition in the lateral superior olive: synaptic responses in mouse brain slice". Hearing Research. 73 (1): 57–64. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(94)90282-8. PMID 8157506. S2CID 34851384.

- ^ Brownell WE, Manis PB, Ritz LA (November 1979). "Ipsilateral inhibitory responses in the cat lateral superior olive". Brain Research. 177 (1): 189–193. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(79)90930-2. PMC 2776055. PMID 497821.

- ^ Darrow KN, Maison SF, Liberman MC (December 2006). "Cochlear efferent feedback balances interaural sensitivity". Nature Neuroscience. 9 (12): 1474–1476. doi:10.1038/nn1807. PMC 1806686. PMID 17115038.

- ^ Bazwinsky I, Bidmon HJ, Zilles K, Hilbig H (December 2005). "Characterization of the rhesus monkey superior olivary complex by calcium binding proteins and synaptophysin". Journal of Anatomy. 207 (6): 745–761. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00491.x. PMC 1571589. PMID 16367802.

- ^ Bazwinsky I, Hilbig H, Bidmon HJ, Rübsamen R (February 2003). "Characterization of the human superior olivary complex by calcium binding proteins and neurofilament H (SMI-32)". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 456 (3): 292–303. doi:10.1002/cne.10526. PMID 12528193. S2CID 22237348.

- ^ Kulesza RJ (July 2008). "Cytoarchitecture of the human superior olivary complex: nuclei of the trapezoid body and posterior tier". Hearing Research. 241 (1–2): 52–63. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2008.04.010. PMID 18547760. S2CID 44342075.

- ^ Warr WB, Guinan JJ (September 1979). "Efferent innervation of the organ of corti: two separate systems". Brain Research. 173 (1): 152–155. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(79)91104-1. PMID 487078. S2CID 44556309.

- ^ a b Schofield BR, Cant NB (December 1991). "Organization of the superior olivary complex in the guinea pig. I. Cytoarchitecture, cytochrome oxidase histochemistry, and dendritic morphology". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 314 (4): 645–670. doi:10.1002/cne.903140403. PMID 1726174. S2CID 2030167.

- ^ Fischl MJ, Burger RM, Schmidt-Pauly M, Alexandrova O, Sinclair JL, Grothe B, et al. (December 2016). "Physiology and anatomy of neurons in the medial superior olive of the mouse". Journal of Neurophysiology. 116 (6): 2676–2688. doi:10.1152/jn.00523.2016. PMC 5133312. PMID 27655966.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Illing RB, Kraus KS, Michler SA (November 2000). "Plasticity of the superior olivary complex". Microscopy Research and Technique. 51 (4): 364–381. doi:10.1002/1097-0029(20001115)51:4<364::AID-JEMT6>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 11071720.

- ^ a b Warr WB, Beck JE (April 1996). "Multiple projections from the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body in the rat". Hearing Research. 93 (1–2): 83–101. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(95)00198-0. PMID 8735070. S2CID 4721400.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schofield BR, Cant NB (March 1992). "Organization of the superior olivary complex in the guinea pig: II. Patterns of projection from the periolivary nuclei to the inferior colliculus". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 317 (4): 438–455. doi:10.1002/cne.903170409. PMID 1578006. S2CID 21120946.

- ^ Shore, Susan E.; Helfert, Robert H.; Bledsoe, Sanford C.; Altschuler, Richard A.; Godfrey, Donald A. (1991-03-01). "Descending projections to the dorsal and ventral divisions of the cochlear nucleus in guinea pig". Hearing Research. 52 (1): 255–268. doi:10.1016/0378-5955(91)90205-N. hdl:2027.42/29434. ISSN 0378-5955. PMID 1648060.

- ^ Gómez-Martínez, Mario; Rincón, Héctor; Gómez-Álvarez, Marcelo; Gómez-Nieto, Ricardo; Saldaña, Enrique (2025-03-01). "Projections from the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body to the dorsal cochlear nucleus in the rat: Morphology, distribution, and cellular origin". Hearing Research. 458 109200. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2025.109200. ISSN 0378-5955. PMID 39923304.

- ^ Smith PH, Joris PX, Yin TC (May 1993). "Projections of physiologically characterized spherical bushy cell axons from the cochlear nucleus of the cat: evidence for delay lines to the medial superior olive". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 331 (2): 245–260. doi:10.1002/cne.903310208. PMID 8509501. S2CID 43136339.

- ^ Wenthold RJ, Huie D, Altschuler RA, Reeks KA (September 1987). "Glycine immunoreactivity localized in the cochlear nucleus and superior olivary complex". Neuroscience. 22 (3): 897–912. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(87)92968-X. PMID 3683855. S2CID 22344089.

- ^ a b Adams JC (April 1983). "Cytology of periolivary cells and the organization of their projections in the cat". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 215 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1002/cne.902150304. PMID 6304156. S2CID 45147218.

- ^ Friauf E, Ostwald J (1988). "Divergent projections of physiologically characterized rat ventral cochlear nucleus neurons as shown by intra-axonal injection of horseradish peroxidase". Experimental Brain Research. 73 (2): 263–284. doi:10.1007/BF00248219. PMID 3215304. S2CID 15155852.

- ^ Kulesza RJ, Berrebi AS (December 2000). "Superior paraolivary nucleus of the rat is a GABAergic nucleus". Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 1 (4): 255–269. doi:10.1007/s101620010054. PMC 2957197. PMID 11547806.

- ^ Kulesza RJ, Spirou GA, Berrebi AS (April 2003). "Physiological response properties of neurons in the superior paraolivary nucleus of the rat". Journal of Neurophysiology. 89 (4): 2299–2312. doi:10.1152/jn.00547.2002. PMID 12612016.

- ^ White JS, Warr WB (September 1983). "The dual origins of the olivocochlear bundle in the albino rat". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 219 (2): 203–214. doi:10.1002/cne.902190206. PMID 6619338. S2CID 44291925.

- ^ Saint Marie RL, Baker RA (August 1990). "Neurotransmitter-specific uptake and retrograde transport of [3H]glycine from the inferior colliculus by ipsilateral projections of the superior olivary complex and nuclei of the lateral lemniscus". Brain Research. 524 (2): 244–253. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(90)90698-B. PMID 1705464. S2CID 21264622.

- ^ Guinan JJ, Norris BE, Guinan SS (1972). "Single Auditory Units in the Superior Olivary Complex: II: Locations of Unit Categories and Tonotopic Organization". International Journal of Neuroscience. 4 (4): 147–166. doi:10.3109/00207457209164756.

- ^ Davis KA, Ramachandran R, May BJ (July 1999). "Single-unit responses in the inferior colliculus of decerebrate cats. II. Sensitivity to interaural level differences". Journal of Neurophysiology. 82 (1): 164–175. doi:10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.164. PMID 10400945.

- ^ Tsuchitani C (March 1977). "Functional organization of lateral cell groups of cat superior olivary complex". Journal of Neurophysiology. 40 (2): 296–318. doi:10.1152/jn.1977.40.2.296. PMID 845625.

- ^ Spirou GA, Berrebi AS (April 1996). "Organization of ventrolateral periolivary cells of the cat superior olive as revealed by PEP-19 immunocytochemistry and Nissl stain". The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 368 (1): 100–120. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960422)368:1<100::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 8725296.