Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Military aircraft insignia

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

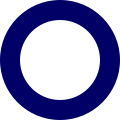

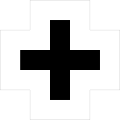

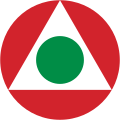

Military aircraft insignia are insignia applied to military aircraft to visually identify the nation or branch of military service to which the aircraft belong. Many insignia are in the form of a circular roundel or modified roundel; other shapes such as stars, crosses, squares, or triangles are also used. Insignia are often displayed on the sides of the fuselage, the upper and lower surfaces of the wings, as well as on the fin or rudder of an aircraft, although considerable variation can be found amongst different air arms and within specific air arms over time.

History

[edit]

France

[edit]The first use of national insignia on military aircraft was before the First World War by the French Aéronautique Militaire, which mandated the application of roundels in 1912.[1] The chosen design was the French national cockade, which consisted of a blue-white-red emblem, going outwards from centre to rim, mirroring the colours of the French flag. In addition, aircraft rudders were painted the same colours in vertical stripes, with the blue vertical stripe of the tricolours forwardmost. Similar national cockades were designed and adopted for use as aircraft roundels by the air forces of other countries, including the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and U.S. Army Air Service.[1]

Germany

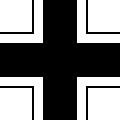

[edit]Of all the early operators of military aircraft, Germany was unusual in not using circular roundels. After evaluating several possible markings, including a black, red, and white checkerboard, a similarly coloured roundel, and black stripes, it chose a black 'iron cross' on a square white field, as it was already in use on various flags, and reflected Germany's heritage as the Holy Roman Empire. The Imperial German Army's mobilisation led to orders in September 1914 to paint all-black Eisernes Kreuz (iron cross) insignia with wide-flared arms over a white field; usually square in shape, on the wings and tails of all aircraft flown by its air arm, then known as the Fliegertruppe des Deutschen Kaiserreiches. The fuselage was also usually marked with a cross on each side, but this was optional. The form and location of the initial cross was largely up to the painter, which led to considerable variation, and even to the white portion being omitted. An iron cross with explicit proportions superseded the first cross in July 1916. Initially, this second cross was also painted on a white field, but in October 1916, it was reduced to a 5 centimetres (2.0 inches) border completely surrounding the cross, even the ends of the flared arms. That same month, the Army's air arm was renamed Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte. In March 1918, a straight black cross with narrow white borders on all sides of the cross was ordered, but proportions were not set until April 1918, resulting in many of those repainted in the field having non-standard proportions. This was then replaced in May by a narrower, straight-armed cross that extended the full chord of wings, with the white border restricted to the sides of the cross's bars. In June, it ceased to be used full chord, with the bars all being the same length. The white on any of these could be omitted when used on a white background, and sometimes on the rudder or on night bombers.

Much like the French roundel, variations of the cross would be used on countries allied with Germany, including the Austro-Hungary (combined with red-white-red stripes on the wings until 1916), Bulgaria, Croatia (stylised as a leaf), Hungary (reversed colours), Romania (a blue-rimmed yellow cross with the tricolour roundel in the middle; the shape was also the stylised monogram of the monarch), and Slovakia (blue cross with a red dot in the middle).

With the dissolution of the German Army's Luftstreitkräfte in May 1920, military insignia would disappear until the rise of the Nazi Party, which imposed new rules on aircraft in 1937, starting with the use of the German red / white / black flag on the tails' starboard side of all aircraft, with the port side showing a Nazi Party flag. When the Luftwaffe's re-establishment was made official, these markings were used by military aircraft, while the 1918 Balkenkreuz crosses were reintroduced. Two standardised proportions of the crosses were introduced by July 1939, with differing widths for the quartet of white 'flanks' on each insignia. When camouflage was introduced prior to the invasion of Poland, the flags were dispensed with, replacing them with a black and white swastika on both sides of the tail. During the ensuing war, the crosses would be further simplified, leaving only the borders in a contrasting colour.

After the Second World War, West Germany reverted to using a variation of the 1916 iron cross, using the white 'flanks' of the Balkenkreuz following the now-curved sides of each arm, while East Germany used a diamond marking based on their flag, with the coat of arms from the flag. The reunification of Germany in 1990 resulted in the West German iron cross replacing the East German insignia for all German military aircraft.

United Kingdom and British Commonwealth nations

[edit]

The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) abandoned their original painted Union Flags because, from a distance, they looked too much like the Eisernes Kreuz (Iron Cross) used on German aircraft. The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) used either a plain red ring (with the clear-doped linen covering forming the light coloured centre), or a red-rimmed white circle on their wings for a short period; almost exactly resembling those in simultaneous use by the neutral predecessors of today's Royal Danish Air Force, before both British air arms adopted a roundel resembling the French one, but with the colours reversed, (red-white-blue from centre to rim). The two separate army and naval air arms joined on 1 April 1918 to form the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The British roundel design, with variations in proportions and shades, has existed in one form or another to this very day.[1][2] The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) roundel was based on the RAF roundel used previously on Canadian military aircraft. From World War I onwards, a variant of the British red-white-blue roundel with the white omitted has been used on camouflaged aircraft, which between the wars meant night bombers. During the Second World War, the colours were toned down and the proportions adjusted to reduce the brightness of the roundel, with the white being reduced to a thin line, or eliminated. In the Asia-Pacific region, the red inner circle of roundels was painted white or light blue to avoid confusion with Hinomaru markings on Japanese aircraft (still used by the Japan Self-Defense Forces to this day), much as the United States roundel omitted the red for the same reason.

After the Second World War, the RAF roundel design was modified by Commonwealth air forces, with the central red disc replaced with a red maple leaf (Royal Canadian Air Force), red kangaroo (Royal Australian Air Force), red kiwi (Royal New Zealand Air Force), and an orange Springbok (South African Air Force); the South African version of the RAF roundel existed until 1958.

United States

[edit]Low-visibility insignia

[edit]

In the later stages of the World War I, the British Royal Flying Corps started using roundels without conspicuous white circles on night-flying aircraft, such as the Handley Page O/400. As early as 1942-43, and again in recent decades, 'low-visibility' insignia have increasingly been used on camouflaged aircraft. These have subdued, low-contrast colours (often shades of grey or black), and frequently take the form of stencilled outlines. Previously, low-visibility markings were used to increase ambiguity as to whose aircraft it was, and to avoid compromising the camouflage, all while still complying with international norms governing recognition markings.

The World War II German Luftwaffe often used such 'low-visibility' versions of their national Balkenkreuz insignia from the mid-war period through to V-E Day, omitting the central black 'core' cross, and only using the 'flanks' of the cross instead, in either black or white versions, which was often done (as an outline only) to the vertical fin or rudder's swastika as well.

Fin flashes

[edit]

This section may contain original research. (August 2021) |

In addition to insignia displayed on military aircraft wings and fuselages, usually in the form of roundels, a fin flash may also be displayed on the fin or rudder.[3] A fin flash often takes the form of vertical, horizontal, or slanted stripes in the same colours as the main insignia, similar to a contemporary tactical recognition flash, and may be referred to as 'rudder stripes' if they appear on the rudder instead of the fin, as with the French Armée de l'Air. Alternatively, a national flag, a roundel or sometimes an emblem or coat of arms may be used.

Gallery of insignia

[edit]Current insignias of national air forces

[edit]Images shown in the following sections are as they appear on the left side of the aircraft (i.e., with the left side of the fin flash leading). In cases where there are no asymmetrical details, such as coats of arms or text that cannot be reversed, the image may be reversed for the right side (such as with the Royal Air Force fin flash) to keep the same side forward, much as with a flag. When a national flag is used, the left side of the aircraft often displays the reverse or back side of the flag as it is normally flown. Exceptions include the German Third Reich's ostensibly 'civilian' aircraft in the 1930s, which used the old black-white-red German flag on the right side of the fin and rudder, and the Nazi Party flag on the left side.

For some countries, a low-visibility variant is also used to avoid compromising aircraft camouflage, and in some cases, to avoid producing a hot spot visible to infrared sensors, such as those used on air-to-air missiles.

-

Angola

(variant 1) -

Angola

(variant 2) -

Argentina

(low visibility) -

Argentine Naval Aviation

(low visibility) -

Armenia

(Variant 1) -

Armenia

(Variant 2) -

Australia

(low visibility) -

Australia

(army aviation) -

-

Bangladesh

(naval aviation) -

Brazil

(low visibility) -

Brazil

(naval aviation) -

-

Brazil

(army aviation) -

-

Canada

(low visibility) -

Chile

(low visibility) -

Chile

(naval aviation) -

-

People's Republic of China

(low visibility) -

Republic of China (Taiwan)

(low visibility) -

Colombia

(low visibility) -

Colombia

(naval aviation) -

-

Croatia

(low visibility) -

Cuba

(Naval Aviation) -

Czech Republic

(low visibility) -

Dominican Republic

(low visibility) -

Ecuador

(naval aviation) -

Finland

(low visibility) -

France

(low visibility) -

France

(Naval Aviation) -

-

Georgia

(low visibility) -

Greece

(low visibility) -

Guatemala

(low visibility) -

Hungary

(low visibility) -

Indonesia

(low visibility) -

Indonesia

(army aviation) -

-

Indonesia

(naval aviation) -

-

Indonesia

(headquarters) -

-

Israel

(low visibility) -

Italy

(low visibility) -

-

Italy

(naval aviation) -

Japan

(low visibility) -

Lebanon

(low visibility) -

Malaysia

(low visibility) -

Malaysia

(alternate) -

-

Malaysia

(naval aviation) -

-

Mexico

(low visibility) -

Mexican Naval Aviation

(low visibility) -

Montenegro

(low visibility) -

Morocco

(naval aviation) -

Netherlands

(low visibility) -

Netherlands

(low visibility, alternate) -

-

-

Nigeria

(naval aviation) -

North Korea

(variant 1) -

North Korea

(variant 2) -

Norway

(low visibility) -

Pakistan

(low visibility) -

Pakistan

(naval air arm) -

-

Panama

(low visibility) -

Peru

(low visibility) -

Peru

(naval aviation) -

-

Philippines

(low visibility) -

Poland

(low visibility) -

Portugal

(low visibility) -

Romania

(naval aviation) -

Saudi Arabia

(low visibility) -

Serbia

(low visibility) -

Seychelles

(Air Force) -

Seychelles

(Coast Guard) -

Slovakia

(low visibility) -

South Africa

(low visibility) -

South Korea

(low visibility) -

South Korea

(naval aviation) -

-

Sweden

(low visibility) -

Thailand

(army aviation) -

Timor-Leste

(variant 1) -

Timor-Leste

(variant 2) -

Timor-Leste

(variant 3/alternate) -

Turkey

(low visibility) -

Turkey

(Naval Aviation) -

Uganda

(alternate) -

Ukraine

(naval aviation) -

United Arab Emirates

(low visibility) -

United Kingdom

(low visibility) -

United Kingdom

(low visibility, light) -

United Kingdom

(low visibility, alternate) -

United States

(low visibility) -

United States

(low visibility, alternate) -

Uruguay

(naval aviation) -

Venezuela

(naval aviation)

Government insignia

[edit]Former insignia of national air forces

[edit]-

Abkhazia

(variant 1) -

Abkhazia

(variant 2) -

Abkhazia

(variant 3) -

Emirate of Abu Dhabi

(1968–1976) -

Afghanistan

(1924–1928) -

Kingdom of Afghanistan

(1929–1965) -

-

-

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

(1979–1983) -

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

(1983–1992) -

Islamic State of Afghanistan

(1992–2002) -

Islamic Republic of Afghanistan

(2010–2021) -

-

People's Socialist Republic of Albania

(1946-1958) -

People's Socialist Republic of Albania

(1958-1960) -

People's Socialist Republic of Albania

(1960-1992) -

-

Algeria

(1962–1964) -

Angola

(1975–1980) -

Angola

(1980–2011) -

Argentina

(naval aviation) -

Australia

(1942–1943) -

Australia

(1943–1946) -

Austro-Hungarian Empire

(1914–1916) -

Austro-Hungarian Empire

(1916) -

Austro-Hungarian Empire

(1918) -

Bahrain

(1972–2002) -

Belgium

(1914) -

People's Republic of Benin

(1975–1990) -

Republic of Biafra

(1967–1970) -

Bophuthatswana

(1987–1994) -

Brazilian Air Force

(1943–1945) -

Kingdom of Bulgaria

(1915–1918) -

Kingdom of Bulgaria

(1938–1941) -

Kingdom of Bulgaria

(1941–1944) -

Kingdom of Bulgaria

(1944–1946) -

People's Republic of Bulgaria

(1946–1992) -

-

-

Canada

(1945–1946) -

Canada

(1946–1965) -

-

-

Republic of China

(1916–1920) -

Republic of China

(1920–1928) -

-

Wang Jingwei regime

(1940–1945) -

Republic of China (Taiwan)

(1928–1991) -

-

-

-

Colombia

(1927–1953) -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

(1960-1964) -

Democratic Republic of the Congo

(1964-1972) -

Costa Rica

(early 1940s-1949) -

Costa Rica

(1964–1994) -

Independent State of Croatia

(1941–1945) -

Croatia

(1991–1994) -

Cuba

(1955–1959) -

Cuba

(1959–1962) -

Czechoslovakia

(1918–1920) -

Djibouti

(1977) -

Dominican Republic

(1947-1950) -

Kingdom of Egypt

(1939–1945) -

Kingdom of Egypt

(1945–1958) -

Egypt

(1958–1972) -

Eritrea

(1994-2000) -

Finland

(1918–1945) -

Free France

(type 1) -

Free France

(type 2) -

German Empire

(1914–1918) -

East Germany

(1955–1959) -

East Germany

(1959–1990) -

Ghana

(1964–1966) -

Haiti

(1942–1964) -

Haiti

(1964–1986) -

Haiti

(1986–1994) -

Kingdom of Hungary

(1938–1941) -

Kingdom of Hungary

(1942–1945) -

Second Hungarian Republic

(1948–1949) -

Hungarian People's Republic

(1949–1951) -

Hungarian People's Republic

(1951–1990) -

Hungary

(1990–1991) -

British India

(1943–1945) -

India

(1947–1950) -

Indonesia

(1946–1949) -

Indonesia

(police aviation) -

-

Iraq

(1931–2003) -

Iraq

(2008–2019) -

Ireland

(1939–1954) -

Japan

(1915-1999) -

-

Democratic Kampuchea

(1976–1979) -

-

-

Khmer Republic

(1970–1975) -

Kingdom of Laos

(1955–1975) -

Latvia

(1918–1940) -

-

Kingdom of Libya

(1962–1969) -

Libyan Arab Republic

(1969–1977) -

Free Libyan Air Force

(2011–2014) -

Lithuania

(1919-1920) -

Lithuania

(1920-1921) -

Malaysia

(1963–1982) -

Malta

(1980–1988) -

Manchukuo

(Air Force) -

Manchukuo

(Air Transport) -

Mauritania

(1960-2019) -

Montenegro

(2006–2018) -

Mozambique

(1975–2011) -

Niger

(1961-1980) -

Netherlands

(1914–1921) -

Netherlands

(1939–1940) -

New Zealand

(1943–1946) -

-

-

North Vietnam

(1955–1965) -

North Yemen

(1957–1962) -

North Yemen

(1962–1990) -

Norway

(1914–1940) -

-

-

Ottoman Empire

(Air Squadrons) -

Ottoman Empire

(Naval Aviation) -

-

Poland

(1918-1921) -

-

-

Portugal

(1914-1918) -

(Southern) Rhodesia

(1939–1954) -

(Southern) Rhodesia

(1963–1970) -

Rhodesia

(1970–1980) -

Kingdom of Romania

(during World War I) -

Kingdom of Romania

(1941–1944) -

Socialist Republic of Romania

(1947–1985) -

Russian Empire

(1912–1917) -

Russia

(1991–2010) -

Serbia

(1912-1915) -

Serbia

(1915-1918) -

Seychelles

(1978) -

Singapore

(1968–1973) -

Singapore

(1973–1990) -

Slovak Republic

(1940–1945) -

Slovak Resistance

(1944) -

Slovenia

(1991–1996) -

Union of South Africa

(1920–1921) -

Union of South Africa

(1921–1927) -

Union of South Africa

(1927–1947) -

Union of South Africa

(1947–1957) -

South Africa

(1957–1994) -

South Africa

(1994–2003) -

South Korea

(1949–2005) -

South Vietnam

(1951–1956) -

South Vietnam

(1956–1975) -

South Yemen

(1968–1980) -

South Yemen

(1980–1990) -

Second Spanish Republic

(1936–1939) -

Spanish State

(1936–1939) -

Spanish State

(wing) -

Spanish State

(fuselage) -

Sri Lanka

(1951–2010) -

Republika Srpska

(variant 1) -

Republika Srpska

(variant 2) -

Sudan

(1956–1970) -

Sweden

(1914–1915) -

Sweden

(1927–1937) -

Sweden

(1937–1940) -

Switzerland

(1914–1947) -

Syria

(1948–1958) -

Syria

(1963–1972) -

Syria

(1972–1980) -

Syria

(1980–2024) -

Tanzania

(1965–2010) -

Tanzania

(2010-2019) -

Thailand

(1940–1941) -

Thailand

(1941–1945) -

Turkey

(1918–1972) -

Turkmenistan

(1991-2011) -

USSR

(1922–1943) -

USSR

(1943–1991) -

Uganda

(1962–2009) -

Ukraine

(1991) -

United Arab Emirates

(1971–1976) -

United Kingdom

(1915–1929) -

United Kingdom

(1929–1938) -

United Kingdom

(1937–1942) -

United Kingdom

(1942–1947) -

-

-

-

United States

(1915–1917) -

United States

(1917–1918) -

United States

(1918–1919) -

United States

(1919–1942) -

United States

(1942–1943) -

United States

(1943) -

United States

(1943–1947) -

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

(1923–1929) -

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

(1929–1941) -

DF Yugoslavia

(1943–1946) -

-

-

SFR Yugoslavia

(1945–1991) -

Serbia and Montenegro (FR Yugoslavia)

(1992–2006) -

-

-

Zambia

(1964–1996)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Kershaw, Andrew (1971). The First War Planes, Friend Or Foe, National Aircraft Markings. BCP Publishing. pp. 41–44.

- ^ "The Royal Air Force Roundel". Royal Air Force History. Royal Air Force. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- ^ Nelson, Phil (7 February 2009). "Dictionary of Vexillology – fin flash". FOTW.net. Flags of the World. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- Robertson, Bruce (1967). Aircraft Markings of the World 1912–1967. Letchworth, England: Harleyford Publications.

External links

[edit]Military aircraft insignia

View on GrokipediaMilitary aircraft insignia are applied markings on the fuselage, wings, and tail of military planes that identify the operating nation's armed forces, service branch, squadron, or specific aircraft, enabling visual distinction from adversaries and civilian objects during combat operations.[1][2] These symbols fulfill both practical roles in preventing friendly fire through rapid aerial or ground recognition and legal requirements under customary international law, where displaying visible national insignia helps define an aircraft's military status and accords combatant protections to its crew.[2][3] The most prominent forms include roundels, circular or geometric emblems often composed of concentric rings in national flag colors placed on wings and fuselage for broad visibility, and fin flashes, rectangular or striped patterns on vertical tail surfaces to aid rear-aspect identification.[1] Originating in the prelude to World War I— with France adopting the first roundel in 1912 and widespread use following by 1914— these markings addressed the chaos of early aerial warfare, where indistinguishable aircraft led to frequent misidentifications.[1][4] Designs vary internationally, with over 80% of nations employing circular roundels derived from cockades or flags, though shapes like stars, crosses, or triangles appear in others, reflecting historical adaptations for clarity under combat conditions.[1] Evolutions in insignia reflect operational demands, such as World War II modifications to avoid enemy mimicry— exemplified by the United States removing the red center from its star insignia to differentiate from Japanese markings— and postwar introductions of low-visibility gray or black variants on tactical aircraft to reduce detectability while retaining identification utility.[4] Additional elements like unit codes, serial numbers, and mission tallies further customize aircraft, though national symbols remain the core for sovereignty assertion in international airspace.[3][4] Debates persist over applicability to unmanned systems, where smaller sizes challenge visibility standards, underscoring the ongoing tension between tradition and modern warfare realities.[2]

Purposes and Functions

Identification Roles

Military aircraft insignia serve a critical function in enabling pilots and observers to rapidly distinguish friendly aircraft from adversaries during high-tempo combat operations, where visual identification at ranges exceeding several kilometers is often the primary means of threat assessment before engagement. Standardized designs, such as concentric circles or bold geometric patterns, are engineered for high contrast against typical backgrounds like sky or cloud cover, providing immediate cues of nationality without reliance on electronic systems that may fail in contested environments.[5] This prevents misidentification leading to friendly fire, which analyses of aerial engagements indicate can account for up to 20% of losses in scenarios with poor visibility or mixed formations.[6] The imperative for such markings stems from the inherent dynamics of aerial warfare, where closure speeds of hundreds of kilometers per hour leave scant time for detailed silhouette analysis; thus, insignia act as a first-principles safeguard, prioritizing unambiguous signaling to minimize causal chains of erroneous attacks. Empirical observations from the Battle of Britain in 1940, where Royal Air Force fighters bore prominent roundels, demonstrate their efficacy in reducing intra-allied shoot-downs during intense intercepts involving over 1,000 sorties daily.[7] Similarly, tactical markings on fuselages and tails aid in assembling formations and maintaining situational awareness among wingmen, ensuring coordinated maneuvers without unintended engagements.[8] In addition to air-to-air roles, insignia facilitate ground-to-air coordination by allowing forward observers and anti-aircraft crews to verify overhead assets as allied, averting premature fire from surface defenses during close air support missions. Bold, recognizable symbols project a deterrent effect by visibly asserting operational presence in contested airspace, signaling resolve to potential foes and reinforcing command of the domain. These elements collectively enhance operational tempo while underscoring the markings' evolution as indispensable for survival in fluid battlespaces.[9][10]Legal and Tactical Requirements

Under customary international humanitarian law, military aircraft are required to display visible external markings indicating their nationality and military character, ensuring distinction from civilian aircraft and adherence to the principle of distinction in armed conflict.[2] This obligation, codified in customary norms and reflected in the influential though unratified 1923 Hague Rules of Air Warfare (Article III), stipulates that such aircraft "shall bear an external mark indicating its nation; and military character."[11] Non-compliance risks misclassification of the aircraft, potentially forfeiting combatant privileges or inviting LOAC violations for failing to clearly signal military status, as unmarked operations could deceive adversaries or obscure targeting decisions.[12] Tactical doctrines mandate strategic placement of national insignia on multiple surfaces—typically upper and lower wing surfaces, fuselage sides, and vertical stabilizers—to maximize multi-angle visibility and facilitate prompt identification by friendly and opposing forces.[10] These requirements draw from operational lessons, particularly World War II, where misidentification due to insufficient markings led to elevated friendly fire risks; Allied forces responded by applying high-contrast "invasion stripes" to aircraft for the June 1944 Normandy operations, reducing errors in cluttered airspace and over beaches.[13] Marking sizes are standardized for practical recognition, with U.S. forces employing wing roundels up to 60 inches in diameter during both world wars to ensure detectability at engagement ranges, building on pre-World War I cockade practices but prioritizing empirical visibility over tradition.[14]Types of Markings

National Insignia

National insignia on military aircraft consist of standardized geometric markings that denote the sovereignty of the operating nation, primarily through shapes like roundels, stars, crosses, and fin flashes incorporating national colors for rapid aerial identification.[1] These designs emphasize simplicity and bold contrasts to facilitate recognition at distance, often featuring concentric circles, five-pointed stars, or cruciform elements scaled proportionally to the aircraft's surfaces.[14] Roundels, the most prevalent form, derive from traditional cockades used in ground forces to distinguish nationalities, adapted into circular patterns with high-contrast hues such as blue outer rings, white centers, and red accents for optimal visibility against sky or ground backdrops.[15] The French tricolor cockade exemplifies this, with its blue-white-red layering mirroring national flag elements while ensuring discernibility from above or below.[7] Similarly, the United States star insignia features a white five-pointed star encircled by blue, sometimes augmented by red and white bars, prioritizing stark outlines over intricate detailing to counter visual blending in combat scenarios.[3][14] Placement of these insignia adheres to principles maximizing multi-angle visibility without aerodynamic disruption, commonly on upper and lower wing surfaces, fuselage sides, and vertical stabilizers.[3] Wing markings, for instance, position the emblem between leading and trailing edges, with diameters calibrated to wing chord lengths—typically 20-30 inches for fighters—to project clearly during high-speed passes while minimizing drag.[14] Such configurations balance identification efficacy with operational stealth, using subdued variants in low-observability schemes where full-color schemes would compromise mission profiles.[16]Unit and Squadron Identifiers

Unit and squadron identifiers on military aircraft consist of alphanumeric codes, tail markings, and serial numbers applied to denote affiliation with specific operational units, enabling efficient ground handling, maintenance tracking, and accountability during large-scale deployments. These markings facilitate rapid visual recognition by personnel for tasks such as refueling, arming, and post-mission analysis, reducing errors in high-tempo environments where hundreds of aircraft from multiple squadrons operate from shared bases. Unlike national insignia, which prioritize external identification, unit codes emphasize internal organization and are often standardized by service regulations to balance visibility with operational security.[17] In the Royal Air Force, squadron codes were formalized in April 1939 via Air Ministry Order 154/39, requiring two-letter identifiers painted on fuselage sides—such as "LR" for No. 56 Squadron—for quick unit differentiation, with a third letter denoting the individual aircraft within the squadron. These codes, initially in medium sea grey for day fighters, supported post-mission accounting and logistics during World War II expansions, where squadrons grew to 12-18 aircraft each. Similar systems persist in modern RAF operations, adapting codes for joint exercises while maintaining traceability.[18] United States military branches employ tail codes and modex numbers for squadron identification; for instance, the U.S. Air Force uses two-letter tail markings on vertical stabilizers to indicate primary unit or base assignment, as seen on F-16s where "FF" denotes the 20th Fighter Wing. U.S. Navy squadrons apply modex numbers—two-digit codes forward of national insignia—for carrier deck operations, distinguishing aircraft like F/A-18s from VF- squadrons amid fleet logistics. Serial numbers, unique per aircraft and formatted by fiscal year (e.g., FY23-001 for recent U.S. procurements), enable historical tracking of maintenance records and transfers across units, with over 13,000 active serials managed by the USAF as of 2023.[19][3][20] Regulations often constrain marking size and contrast to evade detection, particularly in contested environments; during the Vietnam War, U.S. Tactical Air Command mandated subdued stencils in Southeast Asia camouflage schemes from 1965, limiting unit codes to low-visibility greys or blacks measuring 12-18 inches to integrate with disruptive patterns on aircraft like F-4 Phantoms. Branch motifs, such as Navy squadron emblems incorporating anchors for maritime heritage, appear in subdued forms on nose sections for informal unit cohesion without compromising stealth. Nose art, though unofficial and varying by squadron culture, historically supplemented formal identifiers—e.g., WWII B-17 bombers bearing crew-chosen motifs—for morale and ad-hoc recognition, subject to command approval to avoid reflective paints.[21][3]Combat and Operational Symbols

Combat and operational symbols on military aircraft consist of temporary markings applied to denote specific mission outcomes or enhance short-term identification, distinct from permanent national or unit insignia. These symbols emerged during World War I as pilots began tallying verified aerial victories, often using silhouettes of enemy aircraft or other emblems painted near the cockpit to record empirical successes confirmed through witness testimonies or wreckage recovery.[22][23] Such markings served dual purposes: providing verifiable records for official ace credits, which required multiple corroborating sources to prevent inflated claims, and exerting psychological pressure on adversaries by visually advertising pilot prowess.[24] In early examples, World War I American ace Raoul Lufbery adorned his SPAD VII with red swastikas as personal good-luck symbols—predating their appropriation by the Nazi regime and reflecting the emblem's ancient use across cultures for auspicious connotations, including propeller-like motifs appealing to aviators.[25][26] These were not standardized but individually validated by squadron logs and observer reports, underscoring a causal link between documented kills and morale enhancement amid high-casualty dogfights. By World War II, validation shifted to incorporate gun camera footage, enabling precise tallies like the 28 swastika markings (for German aircraft) on P-47 pilots' fuselages, though post-war sensitivities led to phased removal of such symbols.[27][28] Operational symbols, applied for acute tactical needs, include the black-and-white invasion stripes introduced by Allied forces in June 1944 ahead of the Normandy landings on June 6. These alternating bands, painted on wings and fuselages of over 12,000 aircraft including Spitfires and P-51 Mustangs, aimed to mitigate friendly fire risks in the chaotic invasion airspace, where diverse Allied markings could confuse ground anti-aircraft gunners; tests on June 1 confirmed their visibility, and they were mandated by Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory despite initial camouflage concerns.[29][13] The stripes proved effective in reducing misidentifications but were temporary, with removal ordered by December 1944 as aerial superiority stabilized.[29] In contemporary operations, kill markings persist on select platforms to log verified engagements while adhering to operational security, as seen with U.S. Air Force F-15Es displaying drone silhouettes after downing Iranian-launched UAVs in April 2024, confirmed via radar and missile telemetry.[30] A recent instance occurred on September 12, 2025, when a Royal Netherlands Air Force F-35A, during a NATO Air Policing mission over Poland, engaged and destroyed a Russian Geran-2 drone (a Shahed variant), prompting a drone-shaped kill icon beneath the canopy— the first confirmed combat use of such a marking on an F-35, balancing unit morale with discretion in ongoing hybrid threats.[31][32] This practice maintains empirical accountability through sensor data, avoiding unverified boasts while deterring adversaries via subtle deterrence.[33]Historical Evolution

Origins in Early Aviation

The use of cockades as military identifiers traces to 15th-century European armies, where soldiers affixed rosettes or knotted ribbons in national colors to hats and uniforms to enable rapid distinction of allies from enemies in dense, smoke-filled battle environments, thereby minimizing inadvertent fratricide.[15] These devices, often reflecting heraldic or monarchical color schemes, represented a practical evolution from earlier banner-based signaling, prioritizing visible, standardized markers for ground troops operating in visual proximity.[34] With the advent of powered flight around 1908–1910, early aviators—initially drawn from army officer corps—transferred these terrestrial identification methods to aircraft, as air services lacked bespoke protocols and faced analogous risks of misrecognition from ground observers or rudimentary aerial spotting. Lacking radar or radio, pilots relied on painted symbols for over-the-horizon verification during reconnaissance, where mistaking friendly machines for foes could precipitate wasteful or lethal errors in colonial skirmishes or maneuvers. France formalized this adaptation in August 1912, when the Aéronautique Militaire decreed the national cockade—a blue outer ring enclosing white and red circles—as the mandatory marking on all service aircraft wings and fuselages, predating World War I hostilities.[35] This circular tricolor, rooted in the 1789 revolutionary emblem, ensured conspicuous visibility against varied sky and terrain backdrops, directly addressing causal vulnerabilities in France's expanding aerial fleet used for observation in North African campaigns.[36] The United States followed suit in March 1916, when the Army Signal Corps—overseeing aviation—adopted a red star encircled by white as the provisional national insignia, painted on rudders and wings of its nascent fleet amid the Pancho Villa border incursion.[4] This stark, high-contrast design facilitated prompt ground-to-air identification during low-altitude patrols, compensating for the Signal Corps' limited aircraft inventory of about 50 machines and the imperative for swift operational scaling as U.S. involvement in global conflicts loomed.[37] Unlike the French precedent, the American star evoked signaling traditions rather than cockade aesthetics, underscoring pragmatic borrowing from existing corps iconography to equip an underprepared air arm without delaying deployment.World War I Developments

During the early phases of World War I, military aircraft often relied on camouflage schemes without distinctive national markings, which contributed to frequent friendly fire incidents as pilots and ground forces struggled to differentiate friend from foe in the chaos of aerial combat. The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) experienced its first fatalities from such misidentifications shortly after deploying to France in August 1914, prompting urgent reforms. On December 11, 1914, the RFC adopted the red-white-blue roundel—concentric circles mirroring the French design but in reverse order—for wing and fuselage application to enhance visibility and prevent confusion with German aircraft bearing cross motifs. This Type A roundel, formalized in 1915 with bold outlines for better recognition at distance, marked a shift toward standardized insignia driven by after-action reports of combat losses attributable to identification failures.[38][7] In response to Allied adoption of roundels, German forces standardized the black Iron Cross (Eisernes Kreuz) insignia across aircraft starting in September 1914, evolving from an initial Cross Pattée to a straighter form with white borders by mid-war to improve contrast against varied camouflage. This cross, painted on wings and fuselage, addressed similar fratricide risks in the increasingly intense air battles over the Western Front, where over 50,000 aircraft engagements occurred by 1918. Empirical evidence from operational logs indicates that post-adoption, misidentification rates declined as markings provided rapid visual cues, though exact fratricide reductions are not quantified in surviving records; causal analysis attributes fewer erroneous engagements to these visible standards amid the era's high-casualty environment, where air losses exceeded 8,000 for British forces alone. Allied powers, including France with its blue-white-red cockade from 1912 and later U.S. adoption in 1918, mirrored this trend to counter German designs.[39][40] Beyond national symbols, World War I saw the emergence of squadron-specific identifiers, such as tail stripes introduced by the RFC around February 1916, to facilitate formation recognition and reduce intra-allied confusion during cooperative operations. Personal emblems, particularly on German Jasta squadrons from 1916 onward, allowed aces like Manfred von Richthofen to personalize aircraft—often with vibrant nose art or symbols—for verifying combat claims through witness identification in dogfights. British regulations initially restricted such markings to maintain uniformity, but exceptions grew for high-scoring pilots, aiding post-mission attribution in an era where verifiable kills numbered over 20,000 claimed across all sides. These developments prioritized causal clarity in attribution and survival, laying groundwork for tactical marking evolution without encroaching on peacetime refinements.[41][42]Interwar and World War II Changes

In the interwar period, United States military aircraft primarily employed the Type 1 national insignia, featuring a white five-pointed star centered within a blue circular field, with a darker shade of blue adopted gradually during the 1920s for better visibility on painted surfaces.[14] This design, rooted in post-World War I standardization, emphasized identification amid expanding air forces and mechanized operations, with insignia sizes increased proportionally on larger bombers and fighters to maintain visibility from ground and air distances exceeding 1,000 yards.[3] Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, early combat reports highlighted confusion between the U.S. red-centered star variants and the Japanese hinomaru red disc, prompting rapid modifications via War Department and Navy directives. On January 5, 1942, U.S. Navy aircraft added white rectangular bars flanking the blue field to form a horizontal outline, enhancing distinction without altering core colors; Army Air Forces followed suit shortly thereafter under Army-Navy specification AN-I-6a.[3][43] By May 28, 1942, the red center dot was eliminated entirely in the Pacific theater to further mitigate misidentification risks, while European theater aircraft retained it longer due to differing enemy markings, reflecting theater-specific adaptations for causal clarity in multinational operations.[37] The Royal Air Force refined fin flashes during the 1930s, standardizing vertical blue-white-red stripes on tail fins—evolved from World War I rudder markings—for rear-aspect recognition amid faster aircraft and denser formations. These were applied to operational types like the Hawker Hurricane prototypes by 1937, coinciding with camouflage introductions, to address visibility challenges observed in exercises and proxy conflicts such as the Spanish Civil War, where identification errors underscored the need for unambiguous rear identifiers.[44][45] For the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, over 11,500 aircraft received temporary black-and-white invasion stripes—three 18-inch bands alternating on wings and fuselage—as an ad hoc empirical counter to friendly fire risks in foggy conditions and amid thousands of low-level sorties. Ordered by Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory on June 3 but applied starting June 1 in trials, these markings covered fighters, transports, and gliders from RAF, USAAF, and other forces, with rapid application at airfields using brush and paint to achieve near-instant differentiation without relying on existing national insignia alone.[46]Cold War Standardization

Following World War II, the advent of high-speed jet aircraft and the imperatives of nuclear deterrence necessitated greater uniformity in military aircraft insignia to facilitate rapid visual identification and minimize risks of misidentification amid escalating East-West tensions. In the NATO alliance, national insignia retained distinct designs for member states, but efforts focused on interoperable placement and sizing to enhance coalition operations, drawing on shared doctrinal principles rather than a singular emblem. This contrasted with the Warsaw Pact, where Soviet influence promoted the red star as a unifying symbol across allied air forces, emphasizing ideological cohesion over diverse national motifs. Standardization reduced manufacturing discrepancies, as evidenced by empirical adjustments in insignia dimensions and positions that improved production consistency and operational reliability.[47][2] In the United States, the Air Force formalized exterior finishes and markings through Technical Order (T.O.) 1-1-4, first issued in 1964, which prescribed precise locations such as mid-fuselage sides, upper left and lower right wing surfaces, and vertical tails, with sizes scaled to aircraft dimensions (e.g., maximum 50-inch diameter on fuselages). Post-1947 refinements included adding red stripes to the star-and-bar design on January 14, 1947, to evoke national colors, and standardizing wing insignia alignment on September 15, 1951, with the star's point perpendicular to 50% chord for balanced visibility. By March 25, 1965, Air National Guard aircraft adopted these USAF standards, aligning reserve forces with active-duty configurations. These measures addressed variances in earlier production, where inconsistent application had led to identification errors in training and combat simulations.[48][49] The Soviet Union maintained the red star—typically a solid five-pointed design with optional white outlines for contrast—as the core insignia, evolving minimally from wartime patterns to ensure Warsaw Pact uniformity, with allies like East Germany and Czechoslovakia incorporating similar red-star variants on shared MiG and Sukhoi platforms for bloc-wide recognition. This monochromatic approach diverged from NATO's multicolored schemes (e.g., blue-white-red stars in the West), prioritizing simplicity for mass production under centralized planning. On March 31, 1966, U.S. forces in Southeast Asia introduced subdued 15-inch star insignia on camouflaged aircraft, marking an early low-visibility shift driven by jungle operations and radar evasion data, which reduced conspicuousness while preserving identifiability at operational ranges. Such adaptations reflected causal priorities: visual cues optimized for speed and environment, validated by combat feedback showing high-visibility markings increased vulnerability to ground fire.[49][50][2]Post-Cold War Adaptations

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, military aircraft insignia shifted toward low-observability designs to support operations in contested environments emphasizing survivability over peacetime display. These adaptations prioritized integration with camouflage schemes and stealth materials, reducing visual, infrared, and sometimes radar signatures amid asymmetric threats from non-state actors and peer competitors. Coalition exercises increasingly tested these markings for interoperability, ensuring positive visual identification without compromising concealment.[51] Operation Desert Storm exemplified early post-Cold War changes, with coalition forces applying desert-specific camouflage and subdued national insignia. RAF Jaguar GR1As received a specialized low-level paint scheme developed for Thumrait operations, featuring toned-down roundels and serials to match arid terrain and evade ground observation. U.S. aircraft, including A-10 Thunderbolt IIs, incorporated tan or "desert pink" overcoats with stenciled gray or black stars, minimizing contrast against sandy backdrops during low-altitude strikes. These measures addressed empirical needs for reduced detectability, as high-visibility colors from Cold War-era schemes proved liabilities in sunlit deserts.[52][53] Post-9/11 counterinsurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan further subdued insignia on close air support platforms like the A-10, blending national symbols into urban-desert camouflage to counter sniper and MANPADS threats. A-10s accumulated extensive mission tallies—hundreds of bomb symbols on some airframes—while maintaining low-profile stars and bars, enabling persistent loiter without drawing undue attention in populated areas. This approach drew from operational data showing visual cues accelerated enemy targeting in irregular warfare.[54] In high-tech contexts, fifth-generation aircraft like the F-35 Lightning II integrated national insignia directly into radar-absorbent coatings from the 2010s onward, using minimal, low-contrast outlines to preserve stealth profiles during penetration missions. These designs underwent validation in Red Flag exercises, where F-35 formations demonstrated superior survivability ratios—up to 20:1 in simulated engagements—partly attributable to non-reflective markings aiding fusion with sensor data for coalition partners. Such evolutions reflect causal priorities: prioritizing causal chains of detection avoidance over traditional bold identification in networked, multi-domain operations.[55][56]National Variations

European Traditions

European military aircraft insignia traditions trace their roots to World War I, when rapid advancements in aviation necessitated clear visual identification amid fluid alliances and rivalries on the Western Front. France pioneered the use of national cockades in 1912, adopting a concentric blue-white-red design that radiated outward from the center, directly mirroring the colors of the tricolor flag in sequence. This emblem, applied to early aircraft like the Nieuport series, established a model for sequential color banding to denote nationality without ambiguity, influencing subsequent Allied designs while emphasizing sovereignty in multinational operations.[15][35] Germany countered with the Balkenkreuz, a black Iron Cross variant with white borders introduced in April 1918 for Imperial Luftstreitkräfte aircraft, providing high-contrast visibility on fuselages and wings. Post-World War II, the Bundeswehr Luftwaffe readopted a refined version in 1956 upon the force's formation, featuring proportional adjustments such as narrower arms and standardized black-white schematics to invoke pre-Nazi imperial heritage rather than Third Reich associations, ensuring distinct identity in NATO contexts. This evolution underscored a deliberate causal break from wartime symbolism while retaining functional recognition.[57][58] In the United Kingdom, the Royal Air Force developed roundel variants from French inspiration, culminating in the Type D design standardized in June 1947 for post-war aircraft. This brighter iteration—blue outer ring, white middle, red center—omitted wartime yellow surrounds for peacetime aesthetics and visibility, applied uniformly across surfaces. Commonwealth derivatives, such as Australia's incorporation of a red kangaroo within the roundel framework from the 1940s onward, extended this tradition, blending imperial continuity with local fauna to assert federated yet unified identities in joint operations.[35][9] These designs prioritized empirical visibility and national differentiation, with French cockades evolving in scale for jet-era aircraft like the Mirage III (standardized at 1.5 meters diameter by the 1960s for supersonic identification), German crosses maintaining angular precision for ground-to-air recognition, and British roundels adapting hues for low-light conditions, all rooted in WWI's lesson that insignia must withstand high-speed, high-altitude scrutiny without fostering misidentification in coalition warfare.[1]North American Practices

United States military aircraft insignia originated with a red star adopted in March 1916 by the U.S. Army Signal Corps Aviation Section for identification during early aviation operations.[15] This evolved through World War I, incorporating white bars and circles, and by World War II standardized as a white five-pointed star within a blue disk, accented by a red dot in some variants until 1943 when the dot was removed to avoid confusion with Japanese markings.[37] Postwar, the design persisted with refinements for visibility, leading to subdued blue-outlined or gray low-visibility versions by the late 20th century and into the 2020s, applied to enhance survivability in contested environments while ensuring positive identification for hemispheric defense and global deployments.[4] Current U.S. standards require national insignia placement in up to six positions on fixed-wing aircraft—upper and lower wing surfaces bilaterally, and fuselage sides aft of the cockpit—to comply with operational visibility protocols outlined in Technical Order 1-1-4, which governs exterior finishes and markings for Air Force aircraft.[59] These bold, star-based systems prioritize rapid visual recognition in expeditionary forces, distinguishing U.S. platforms amid allied operations without reliance on European-style concentric circles or bars. Canadian practices integrate the maple leaf into roundel designs post-World War II, with the Royal Canadian Air Force adopting an initial maple leaf variant in 1946 within a red-white-blue bullseye inherited from British Commonwealth influences.[9] By the late 1940s, a refined version featuring a central red maple leaf on white surrounded by blue and red annuli became standard, reflecting pragmatic adaptation for national distinctiveness while maintaining interoperability in North Atlantic Treaty Organization contexts.[60] This approach underscores North American emphasis on symbolic clarity over ornate motifs, applied consistently to fighters and trainers for defensive patrols and joint missions. Exported U.S. aircraft, such as the F-16 Fighting Falcon supplied to allies including Turkey and Israel since the 1980s, typically receive recipient national insignia upon delivery, though initial U.S. configurations and sustainment packages ensure compatibility with American identification standards to facilitate training and logistics under Foreign Military Sales agreements. This dual-aspect compliance supports empirical interoperability without mandating uniform markings, allowing operators to balance local symbolism with U.S.-origin platform requirements.Asian and Other Regional Designs

In East Asia, the People's Liberation Army Air Force adopted a red five-pointed star within a yellow circle as its primary roundel upon formal establishment in November 1949, drawing from Soviet-influenced communist iconography to assert national sovereignty amid civil war remnants and early Cold War tensions.[61] This marking replaced earlier provisional designs used on captured Nationalist aircraft from 1946 to 1949, which featured simplified curved stars, emphasizing ideological distinction over pre-1949 Republic of China variants._%E2%80%93_People%27s_Liberation_Army.svg) Japan's Air Self-Defense Force, formed in 1954 under U.S. postwar oversight, retained the imperial red disc (hinomaru) on a white background, a continuity from pre-1945 Imperial Japanese Army and Navy usage that symbolized national identity while complying with Allied occupation mandates for non-militaristic aviation. South Asian air forces often incorporated flag-derived elements to mark post-colonial independence. The Indian Air Force transitioned from Royal Air Force-style roundels in 1947–1948 to a blue-ringed Ashoka Chakra (wheel) on orange-white-orange bands by 1950, reflecting the Republic of India's tricolor and ancient imperial symbolism for operational distinction from British Commonwealth markings.[62] This design facilitated identification during conflicts like the 1947–1948 Indo-Pakistani War, where Soviet and Western aircraft acquisitions necessitated standardized yet nationally assertive insignia.[63] In the Middle East, Israeli Air Force aircraft have borne a blue Star of David within a white disc since the service's inception on May 28, 1948, serving as a compact national emblem amid immediate Arab-Israeli hostilities and lacking traditional fin flashes to prioritize squadron-specific markings for tactical flexibility. Saudi Arabia's Royal Air Force, established in the 1920s and modernized via U.S. technical aid from the 1940s onward, employs a green disc with a white palm tree and crossed swords—mirroring the kingdom's flag—for aircraft like F-15 Eagles, blending Arab nationalist colors with Western operational standards in desert environments.[64] These designs underscore superpower influences, with U.S.-supplied platforms requiring adapted markings to avoid misidentification in joint exercises, while asserting regional autonomy through flag-derived motifs.[65]Specialized Markings

Fin Flashes and Rudder Stripes

Fin flashes and rudder stripes serve as vertical tail markings on military aircraft, designed specifically for rear-aspect identification during pursuits, evasions, and fleet operations where tail-on views predominate. These markings facilitate rapid nationality recognition at operational distances, minimizing misidentification risks in combat scenarios distinct from side or planform views addressed by fuselage roundels.[66][1] The United Kingdom pioneered standardized fin flashes during World War I, with vertical tricolor stripes—red nearest the leading edge, followed by white and blue—applied to rudders in June 1915 before relocation to the fin to prevent aerodynamic imbalance from uneven paint weight. This reversed French tricolor order distinguished British aircraft from Allied French ones using similar rudder striping on the Western Front. Postwar, the design became the rear-view standard for Royal Air Force and Commonwealth air forces, ensuring visual consistency across fleets into the interwar and World War II eras, with red/blue variants on camouflaged aircraft retaining the red-forward sequence.[66][44][67] In the United States, World War II-era rudder stripes featured alternating red and white bands, specified as 13 equal-width stripes—7 in insignia red and 6 in insignia white—on naval aircraft rudders, with red positioned forward nearest the hinge for European theater operations. These markings, rooted in prewar national insignia practices, were discontinued on camouflaged Army Air Forces aircraft by 1943 to prioritize concealment but persisted on some types into late 1942. Postwar jet aircraft largely phased them out for reduced drag and visibility, though red-white stripes remain on modern trainers such as the T-6 Texan II for instructional identification.[3][14] German vertical tail markings drew from imperial black-white-red colors during the interwar Reichswehr period for historical signaling continuity, applied as vertical stripes on the fin or rudder, though Luftwaffe aircraft in World War II emphasized unit-specific codes over uniform national flashes, with the swastika often centered on the tail fin. Such variations optimized rear recognition while integrating with tactical camouflage needs.[68]Low-Visibility and Stealth Variants

Low-visibility markings on military aircraft reduce contrast between insignia and the airframe's camouflage to shorten enemy visual acquisition ranges, thereby enhancing survivability without fully eliminating identification features required under international law. These schemes prioritize subdued tones, such as black or dark gray outlines, over high-contrast colors, limiting detectability from ground observers or other aircraft at typical engagement distances. Empirical assessments indicate that such reductions can decrease visual detection probability by factors of 2 to 5 times compared to full-color variants, depending on background and lighting conditions.[69][70] In the United States Air Force, low-visibility adaptations accelerated in the 1980s with the introduction of schemes like Hill Gray (FS 36118), applied to fighters such as the F-16, which toned down national stars and bars to near-invisible stencils against gray undersurfaces. This evolution addressed lessons from Vietnam-era operations, where high-visibility markings increased vulnerability to anti-aircraft fire, prompting a shift toward overall aircraft camouflage integration by the late 1970s. Stealth platforms exemplified further minimization: the F-117 Nighthawk, operational from 1983, initially flew without external national insignia to preserve radar cross-section (RCS) secrecy and low-observability, relying on mission-specific internal coding before adding faint gray stencils in later years.[50][71] Subsequent designs like the F-22 Raptor incorporated minimal low-visibility roundels on the aft fuselage and wing, using radar-absorbent materials that also dampen visual and infrared signatures, ensuring compliance with Laws of Armed Conflict (LOAC) provisions mandating distinguishable markings. These are positioned for aerial identification while avoiding high-RCS protrusions or reflective paints. By the 1990s, most USAF combat aircraft adopted such variants, with studies confirming reduced acquisition times in simulated engagements.[72][73][74] Contemporary advancements include multi-spectral coatings developed in the 2010s and 2020s, which integrate visual camouflage with infrared suppression and RCS reduction, applied over low-visibility insignia to maintain LOAC adherence—such as retaining outline shapes visible at close range—while minimizing signatures across wavelengths. For instance, NATO allies like Australia employ dark gray roundels on F-35s, balancing stealth imperatives with the 1907 Hague Convention's requirement for non-deceptive military emblems. These paints empirically lower thermal detectability by up to 50% in tests, supporting operations in contested environments without compromising legal identifiability.[75][76][74]Legal Framework and Controversies

International Law on Markings

Customary international law requires military aircraft to display external markings indicating their nationality and military character to distinguish them from civilian aircraft and ensure compliance with the principle of distinction under the law of armed conflict (LOAC).[2][12] This obligation, rooted in state practice and expert consensus, prevents deception that could invite protected status under international humanitarian law.[74] The foundational text influencing this custom is Article III of the 1923 Hague Rules of Air Warfare, which states: "A military aircraft shall bear an external mark indicating its nation; and military character," though the rules remain unratified, their provisions reflect binding customary norms applicable in aerial warfare.[11] Failure to adhere constitutes perfidy under Article 37 of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (1977), prohibiting feints of civilian or neutral status to betray enemy confidence in protections afforded to non-military objects. Such violations expose aircraft, crew, and operations to immediate targeting without the protections otherwise granted to lawfully marked military assets, as unmarked operations risk prosecution for unlawful combat methods.[2][77] Unlike civil aviation, governed by the 1944 Chicago Convention and ICAO standards requiring nationality and registration marks, no equivalent multilateral treaty mandates specific formats for military aircraft markings; national standards prevail but must satisfy LOAC visibility requirements to avoid misidentification.[77] Interpretations by organizations like the International Committee of the Red Cross emphasize that markings must be sufficiently visible from relevant distances and conditions to enable attribution, drawing analogies from protective emblem rules under Geneva Conventions Article 42, which prioritize detectability for compliance.[78] Empirical enforcement occurs through incident-specific accountability, where state practice in conflicts—such as engagements of inadequately marked aircraft—reinforces the norm, with tribunals assessing perfidy based on intent to deceive via absence or obfuscation of emblems.[74][79]Debates Over Visibility and Symbolism

Kill markings on military aircraft, denoting confirmed enemy victories, have served a dual purpose historically. Originating in World War I, where pilots like the British Royal Flying Corps' aces tallied verified kills with symbols such as swastikas or bomb icons to track scores, these emblems boosted pilot morale and squadron prestige by providing tangible evidence of success in an otherwise uncertain combat environment.[23] In World War II, Allied and Axis forces alike used them for propaganda, with photographs of marked aircraft elevating aces to heroic status and sustaining public support amid prolonged attrition warfare.[24] However, some commanders expressed reservations, viewing the displays as potential gloating that could personalize conflicts unnecessarily, though pilots often prioritized them for unit cohesion over such concerns.[80] No historical analyses indicate these markings empirically escalated enemy retaliation or targeting of high-scoring pilots beyond baseline combat risks driven by tactical proficiency.[81] Symbolism in aircraft insignia has sparked contention, particularly with pre-1930s uses of the swastika as a neutral emblem unrelated to later ideologies. Adopted by the Finnish Air Force in 1918 as a badge of honor derived from ancient good-fortune motifs—predating Nazi appropriation by over a decade—and similarly employed by early U.S. and Latvian aviation units for luck or victory tallies, the symbol functioned practically without ideological baggage until the 1930s.[82] Postwar debates over retaining such historical markings on restored aircraft or models often pit evidentiary accuracy against contemporary offense sensitivities, with proponents arguing erasure distorts causal understanding of aviation traditions, while critics cite public misinterpretation risks; Finland quietly phased out its swastika insignia by 2020 amid external pressures, despite no intrinsic link to Nazism in its original context.[83] Empirical utility—such as rapid visual distinction in dogfights—outweighs symbolic reinterpretations, as first-hand accounts from interwar pilots confirm the emblem's role in unit identity without provoking escalation.[84] Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) intensify visibility debates under the law of armed conflict (LOAC), where irregular or minimal markings challenge traditional identification requirements. The U.S. MQ-9 Reaper, for instance, bears subdued national insignia on wings and fuselage to balance stealth with distinction obligations, but analyses question efficacy in swarm operations where hundreds of small drones could blur friend-foe lines, potentially violating LOAC principles of precaution and discrimination absent technological aids like transponders.[2] A 2022 examination of customary air warfare rules affirms that UAVs must display external markings visible from distance to enable humane targeting decisions, rejecting camouflage as a ruse that negates perfidy prohibitions, yet swarm dynamics—envisioned in doctrines for overwhelming defenses—causally demand adaptive solutions like electronic IFF over painted symbols alone, as visual cues degrade at scale.[2] Data from recent conflicts, including over 3,400 U.S. reconnaissance sorties in Vietnam-era precursors, underscore that under-marked drones risk misidentification without proven morale or escalation effects akin to manned kill tallies.[85]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roundel_of_Saudi_Arabia.svg

_(30273241577).jpg/250px-Bristol_F2b_Fighter_‘D8096_D’_(G-AEPH)_(30273241577).jpg)

_(30273241577).jpg/2000px-Bristol_F2b_Fighter_‘D8096_D’_(G-AEPH)_(30273241577).jpg)