Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

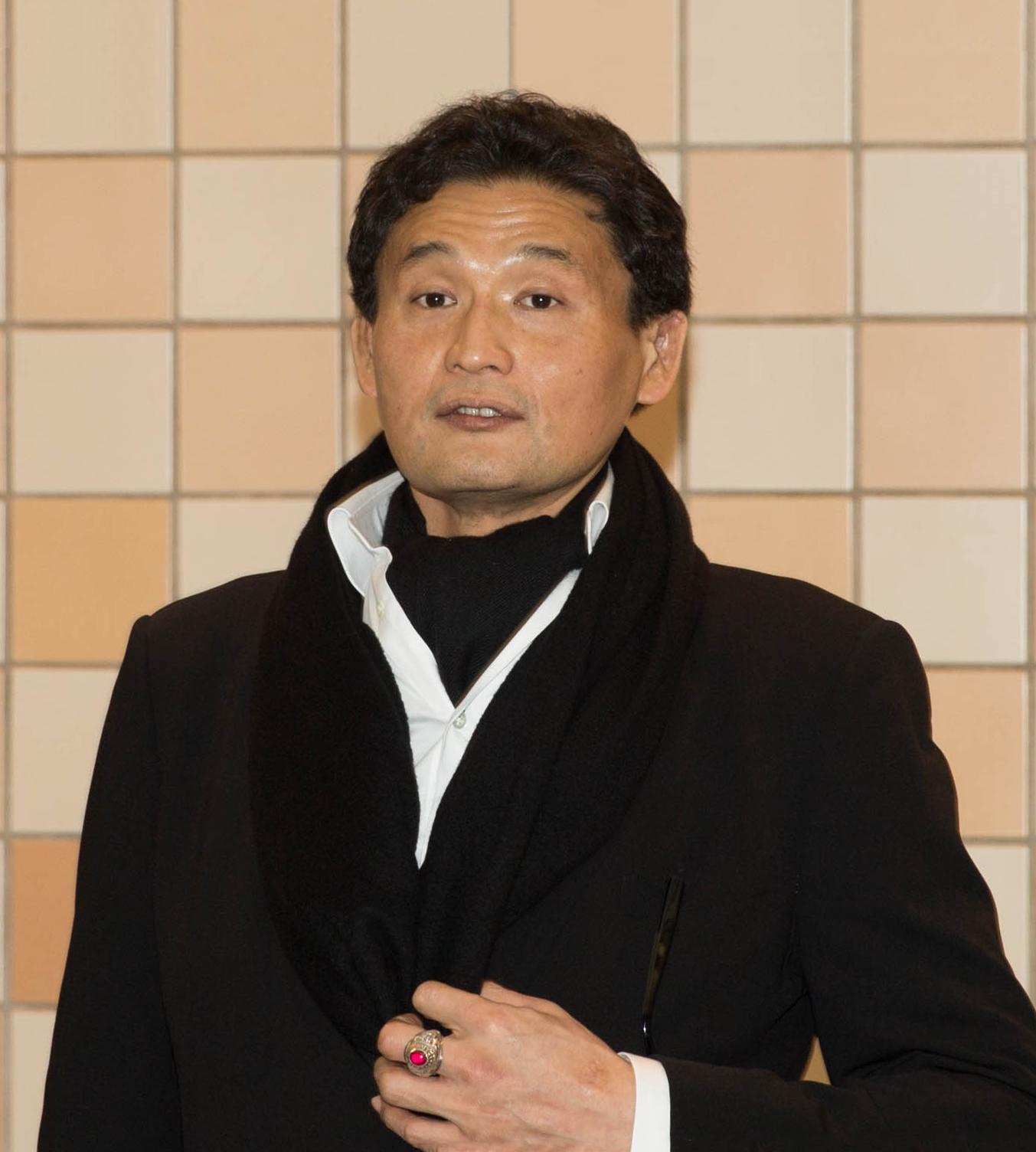

Takanohana Kōji

View on WikipediaTakanohana Kōji (Japanese: 貴乃花 光司, Hepburn: Takanohana Kōji; born August 12, 1972, as Kōji Hanada (花田 光司, Hanada Kōji)) is a Japanese former professional sumo wrestler and coach. He was the 65th man in history to reach sumo's highest rank of yokozuna, and he won 22 tournament championships between 1992 and 2001, the sixth highest total ever. The son of a popular ōzeki ranked wrestler from the 1970s, Takanohana's rise through the ranks alongside his elder brother Wakanohana and his rivalry with the foreign born yokozuna Akebono saw interest in sumo and attendance at tournaments soar during the early 1990s.[1]

Key Information

Takanohana was the youngest ever to reach the top division at just 17, and he set a number of other age-related records. He had a solid but aggressive style, looking to get a right hand grip on his opponents' mawashi and move them quickly out of the ring.[1] He won over half his bouts by a straightforward yorikiri, or force out.[2] In his later career he suffered increasingly from injuries, and he retired in January 2003 at the age of 30. He became the head coach of Takanohana stable in 2004 and was on the board of directors of the Japan Sumo Association from 2010 until January 2018, when he was removed and demoted in the Sumo Association's hierarchy. He resigned from the Sumo Association in September 2018.

Background

[edit]Takanohana comes from a family with a great sumo history, sometimes called the "Hanada Dynasty."[3] His uncle Wakanohana Kanji I was a yokozuna from 1958 to 1962, and his father Takanohana Kenshi had held the second highest rank of ōzeki for a then record 50 tournaments from 1972 to 1981. Upon his retirement his father established the training stable (heya) Fujishima stable. The young Kōji Hanada had been practicing sumo since elementary school and won the equivalent of a yokozuna title in junior high school.[4] Upon his graduation in 1988 he formally joined his father's stable. His elder brother Masaru had been planning to complete high school but dropped out so as not to lag behind his brother.[4]

Early career

[edit]

Takanohana and his brother made their professional debuts together in March 1988, with future rival Akebono also beginning his career in the same month.[5] The two brothers had to move from the family quarters in the stable and join the communal room with all the other new recruits.[6] They were also instructed not to refer to their parents as "father" and "mother" any more but as "oyakata" and "okamisan" (coach and coach's wife).[7] Kōji initially wrestled under the name Takahanada (貴花田), and it was understood that he would only be allowed to adopt his father's shikona of Takanohana (meaning noble flower)[8] when he reached the rank of ōzeki.[5]

Their early career attracted much publicity, with each divisional promotion regarded by the media as part of an inevitable rise to the top ranks.[3] Takahanada's progress was rapid and he set numerous age-related records, including the youngest ever makushita division tournament champion (16 years 9 months),[4] youngest ever promoted to the second highest jūryō division (17 years 3 months),[4] and the youngest ever promoted to the top makuuchi division (17 years 8 months).[4]

In March 1991, in his fourth top division tournament, Takahanada was runner-up with twelve wins, and became the youngest ever sanshō or special prize winner, receiving awards for Fighting Spirit and Technique. In the following tournament in May 1991 he defeated veteran yokozuna Chiyonofuji in a match watched by 44 percent of the Japanese population on TV,[5] becoming the youngest ever to defeat a yokozuna.[4] Chiyonofuji retired two days afterwards.[9] In January 1992, he became the youngest ever top division tournament champion (19 years 5 months).[4] He was too young to drink the celebratory sake at the after tournament party, and had to make do with oolong tea instead.[4] After his second championship in September 1992, followed by two good scores of 10–5 and 11–4 in the next two tournaments, he was promoted to ōzeki in January 1993, the same tournament in which Akebono was elevated to yokozuna.[5]

During this period the two brothers created a so-called "Waka-Taka boom" and were credited with restoring sumo's popularity, particularly amongst younger audiences.[10] Interest in sumo rose to its highest level since the era of Futabayama in the 1930s,[7] with official tournaments (honbasho) selling out of tickets every day. Both Takahanada and his brother became sex symbols.[11]

Promotion to yokozuna

[edit]Now known as Takanohana (貴ノ花), he was also the youngest ever to be promoted to ōzeki at 20 years 5 months.[12] With the foreign born Akebono as sumo's only yokozuna, there was a great weight of expectation on Takanohana to make the next step up.[5] However, his lack of consistency, and Akebono's dominance, delayed his promotion to yokozuna.[5] He won his third championship in May 1993, but lost a playoff to Akebono in the following tournament in July, and even produced a make-koshi or losing record of 7–8 in November. In 1994, a year in which Akebono suffered several injury problems, Takanohana won the January and May tournaments, but was then outshone by Musashimaru, who won in July with a perfect 15–0 record.[5] After taking the September 1994 championship, Takanohana now had six top division titles, but none had been won consecutively. No previous wrestler had ever accumulated so many titles before reaching sumo's highest rank. The Sumo Association nominated him for yokozuna after the September tournament, but the Yokozuna Deliberation Council failed to endorse it by the required two-thirds majority, the first time this had happened in twenty five years.[13] They insisted that two consecutive championships were required, having demanded the same of Akebono before his promotion.[5] After changing the spelling of his shikona in November 1994, Takanohana at last managed to win two consecutive tournaments, with his second consecutive unbeaten 15–0 score, and his promotion was confirmed.[5] He had been at the ōzeki rank for 11 tournaments, or nearly two years. However, at 22 years and 3 months, he was still the third youngest yokozuna ever at the time.[14]

Yokozuna career

[edit]1995–1997

[edit]Takanohana's total of seven tournament championships by the start of 1995 was the same as the total won by Akebono, who had reached the yokozuna rank two years before him.[3] However, Takanohana now pulled ahead of his rival. He was at his peak as a yokozuna between 1995 and 1997, during which time he won 11 of the 17 tournaments he entered, finishing runner-up in the other six.[15] He produced two more perfect scores of 15–0, in September 1995 and September 1996. Overall he won 80 out of 90 bouts he fought in 1995, 70 out of 75 in 1996, and 78 out 90 in 1997, far ahead of any other wrestler. In three of the tournaments Takanohana did not win during this period, he was defeated by stablemates in playoffs: once to Wakanohana and twice to ōzeki Takanonami.[16] Sumo rules prevent wrestlers from the same heya meeting in regular tournament bouts (playoffs excepted) which meant Takanohana avoided not only his brother and Takanonami but also sekiwake Akinoshima and Takatōriki.[5] The merger of his father's Fujishima stable with his uncle's Futagoyama stable in 1993 had added even more top division wrestlers to this list, giving him an advantage over Akebono, who had to face them all.[5] By September 1996 Takanohana had won 15 tournament championships, and was still only 24 years old. However, after sitting out the first tournament of his career in November 1996 due to a back injury suffered on a regional tour, he put on more weight and began to be more susceptible to injury and illness.[1]

1998–2000

[edit]Takanohana was affected by a liver disorder in the first half of 1998, which caused him to withdraw from the January 1998 tournament and miss the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Nagano (his place was taken by Akebono).[17] He pulled out of the March 1998 tournament as well and was still below his best in May. Shunning the traditional treatment methods available from his stable, he turned instead to a physical therapist called Tashiro Tomita, who had a considerable influence over him.[3] He became increasingly isolated from his father and brother, with his father claiming Takanohana had been "brainwashed" by Tomita.[3] Despite his brother's promotion to yokozuna that year, creating the first ever sibling grand champions,[12] the two were barely on speaking terms.[18] Takanohana recovered to win the July and September 1998 tournaments, and was runner-up that November. In 1999, however, he was even more badly affected by injuries, including a dislocated shoulder,[1] and managed only one score in double digits all year.[15]

After making peace with his family,[19] Takanohana regained some of his consistency in 2000, although he was temporarily sidelined by an elbow injury suffered in the July tournament.[20] His brother had retired in March, and several other members of his stable were now past their best.[7] With Akebono dominant once more, his best results that year were two runner-up performances.

2001–2003

[edit]Takanohana won his first tournament in over two years in January 2001, winning his first fourteen bouts and then defeating fellow yokozuna Musashimaru in a playoff on the final day. He won his final championship in May 2001, again in a playoff against Musashimaru, but it came at a great cost. He had suffered serious knee ligament damage in a loss to Musōyama on the 14th day but he insisted on fighting until the end of the tournament.[3] As a result, he then missed an unprecedented seven consecutive tournaments, undergoing surgery in Paris in July 2001 and having a lengthy recuperation after that.[21]

Takanohana finally returned to the ring in September 2002, after the Sumo Association declared he must compete or retire.[22] He finished behind Musashimaru on 12–3, the 16th time he had been a tournament runner-up. Considering how long he had been away, it was seen as an impressive comeback.[23] However, he sat out the next tournament with a recurrence of the knee injury.[24] He made another comeback in January 2003, making a late decision to compete. A shoulder injury caused him to miss two days, and after suffering successive losses to Dejima and Aminishiki he announced his retirement.[1] He said he had no regrets and was thankful to have achieved so much in sumo.[1] His father spoke of his relief at the decision, after seeing his son battle through so many injuries.[1] Takanohana's record of 22 tournament championships was the fourth best in sumo history, behind only Taihō, Chiyonofuji and Kitanoumi at the time.[25] Junichiro Koizumi, the Prime Minister, was among those paying tribute.[25] His retirement left no Japanese born wrestlers at the yokozuna rank and was widely regarded as being the end of an era.[25]

Takanohana's danpatsu-shiki, or official retirement ceremony, was held at the Ryōgoku Kokugikan on June 1, 2003. Unusually, Takanohana allowed only 50 guests on stage to take a snip of his hair, instead of the normal 300 to 400.[26] The ceremony, and the party held afterwards at the Imperial Hotel, were both broadcast live on Fuji TV.[27]

Fighting style

[edit]Takanohana was largely a yotsu-sumo wrestler, favoring techniques which involved grabbing his opponent's mawashi or belt. His preferred grip was migi-yotsu (right hand inside, left hand outside his opponent).[28] His most common winning kimarite by far was yori-kiri, a simple force out, which accounted for 52 percent of his victories.[2] He also regularly employed uwatenage, or overarm throw, and this was the technique he used to defeat Asashōryū in the second of their two meetings, in September 2002.[2]

Retirement from sumo

[edit]

After his retirement he became an elder (or member) of the Japan Sumo Association. Because of his great achievements in sumo he was given a bonus of 130 million yen and was also made a "one generation" elder without having to purchase a share in the Association.[1] This enabled him to keep his fighting name and he was now known as Takanohana Oyakata.[1] With his father's health failing, he took over the operation of his training stable in January 2004, renaming it Takanohana stable.[29] Its last sekitori, Takanonami retired shortly afterwards.[3][30] During 2008, he added four new recruits to his stable, the first for several years, bringing the total number of wrestlers in his charge up to ten.[31] These include his first foreign recruit, a Mongolian with amateur sumo experience named Takanoiwa,[32] and two twins.[33] In July 2012 Takanohana produced his first sekitori level wrestler when Takanoiwa was promoted to the second highest jūryō division. He won the jūryō championship in January 2013 and a year later was promoted to the top makuuchi division. Takanohana also coached Takakeishō, who reached the top division in January 2017.[34]

Takanohana became a judge of tournament bouts in February 2004, only a year after his retirement, a role for which elders normally have to wait at least four years.[35] After the election of the Association's Board of Directors in February 2008, the Association appointed Takanohana as Associate Manager of Judging (審判部副部長, shimpanbu-fukubuchō), replacing former yokozuna Chiyonofuji who was elected to serve the Board as a director.[36][37] For an organization that tends to follow seniority over achievement in its organization appointment, it was highly unusual for them to place a 35-year-old to such an influential position. However both former yokozuna, Kitanoumi and Chiyonofuji whom Takanohana is often compared to, served a stint as Associate Manager of Judging prior to their becoming the Board director.[38] In February 2009 he was moved from the judging department to the jungyō (regional tour) department, a less high-profile position.[citation needed]

Takanohana mentioned in October 2009 that he was interested in running for a spot on the Board of Directors in the February 2010 elections, and confirmed in January that he would stand, despite the fact that this would mean opposing the two officially sanctioned candidates of the Nishonoseki ichimon or group of stables. As a result, Takanohana and six of his supporters, Ōtake (the former Takatōriki), Futagoyama (the former Dairyū), Otowayama (the former Takanonami), Tokiwayama (the former Takamisugi), Ōnomatsu (the former Masurao), and Magaki (the former Wakanohana II) left the Nishonoseki ichimon.[39] Takanohana told a press conference, "I will leave the faction. I bid farewell to everyone in my greetings at the meeting. I have stepped into the race as a candidate."[40] The first contested elections since 2002, they took place by secret ballot on February 1, and Takanohana was elected to the board, replacing Ōshima.[41] Seen as a reformer, he favored revamping the current ticket sales system and improving support for ex-rikishi, as well as encouraging sumo in primary schools, raising the pay of gyōji, yobidashi and tokoyama, and making public the Sumo Association's accounts and assets.[42] His victory was praised by the Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, who said Takanohana had let in "a new wind of change."[43] In 2014, the JSA made the decision to recognize the Takanohana group formed from the stables ousted in 2010, as an official ichimon.[44]

In July 2010, in the wake of a scandal involving several wrestlers admitting to illegal gambling, he denied he had connections with members of the yakuza underworld after media reports that he was seen with a mobster during a visit to Ehime Prefecture to recruit new apprentices.[45]

Following the election of Hanaregoma as the new head of the Sumo Association in August 2010, Takanohana returned to the judging department as director of judging.[46] At 38 he was the second youngest director of judging in the history of the Sumo Association.[47] The following month he and his wife were awarded ¥8.47 million in damages by the Tokyo High Court over 13 articles published by the Shukan Gendai and Gekkan Gendai in 2004 and 2005 concerning match-fixing allegations and the controversy over his father's inheritance.[48] He left the judging department once again in 2012 and became the director of the Osaka tournament.[citation needed]

Having reached a peak weight of 160 kg (350 lb) as an active wrestler, he has lost a great deal of weight since his retirement (more than retired wrestlers typically do) and is now around 90 kg (200 lb).[49] In 2009 he published a book detailing his weight loss methods.[citation needed]

He ran for the chairmanship of the Sumo Association in 2016, but was defeated by Hakkaku Oyakata (ex-yokozuna Hokutoumi).[50] Following this he was replaced as General Enterprises Director, seen as the third highest position in the Association's hierarchy, by Kagamiyama Oyakata, and became the jungyo (regional tour) director.[51]

Takanoiwa affair and resignation

[edit]Takanohana was criticized for his delay in notifying the Sumo Association that Takanoiwa would miss the November 2017 tournament because of injuries allegedly sustained in an assault by the yokozuna Harumafuji at a restaurant in Tottori Prefecture in late October.[52] Takanohana reported the incident to the police but did not submit a medical certificate for his wrestler until near the start of the tournament.[52] Takanohana refused to speak to the press about the incident or co-operate with the Sumo Association's investigation.[53] An editorial in the Nikkei Asian Review compared his actions to "an executive withholding from top management information that could rock the company."[54] Sumo writer Chris Gould said Takanohana was under fire for breaking sumo's code of secrecy by going to the police, whereas "in most other sports he'd be lauded as a whistleblowing hero."[55] It was announced after a meeting of sumo elders on December 1, 2017, that Takanohana would only talk to the Sumo Association's crisis management team once the police investigation was concluded.[56] On December 28 an emergency meeting of the board of directors recommended unanimously to dismiss Takanohana as a director for failing to promptly report Takanoiwa's injuries to the Sumo Association, and for failing to co-operate with the investigation.[57] Their recommendation was certified by a meeting of Sumo Association councilors and external members on January 4, with Takanohana demoted two rungs in the hierarchy.[47] It is the first time that a director has been dismissed before the end of his scheduled term.[58] He failed to gain re-election to the board in the February 2018 elections, receiving only two votes in the ballot.[59] The Takanohana group had selected Ōnomatsu Oyakata (the former sekiwake Masurao), as their preferred candidate and he was duly elected, but Takanohana decided to run as well.[60] In March 2018 Takanohana was demoted again, to the lowest rank of toshiyori, due mainly to the behavior of his wrestler Takayoshitoshi, who was suspended for one tournament for punching his attendant in the dressing room after a match.[61] He returned to the shimpan or judging committee.[62]

On September 25, 2018, Takanohana announced his resignation from the Japan Sumo Association, after refusing to disavow the allegations in a letter of complaint that he filed with the Cabinet Office on March 9 over the Association's handling of the Takanoiwa affair. Although he withdrew the letter later that month following Takayoshitoshi's misbehavior, in August the Association demanded that he disavow what he wrote as "totally false", but he refused.[63] He also announced that Takanohana stable will be dissolved with its wrestlers transferring to Chiganoura stable. He called his decision "agonizing and gut-wrenching" but said he could not "bend the truth and say that what was in my complaint was untrue."[64] The JSA in response denied pressuring Takanohana to do this, or to align his stable with an ichimon, and spokesman Shibatayama said they had not yet accepted his resignation as Takanohana had not used the correct documents.[65] They accepted Takanohana's retirement, and the closure of Takanohana stable, on October 1, 2018.[66] He received 10 million yen for retirement and bonuses, and has been allowed to use the name "Takanohana" outside of the sumo world.[67]

In a press conference on May 19, 2019, Takanohana announced he would be establishing the Takanohana Dojo organization to promote sumo worldwide. He also ruled out any suggestion that he would enter Japanese politics.[68]

Relationship with family

[edit]The Hanada family had generally received very positive press coverage while Takanohana and Wakanohana were active wrestlers, with the press holding them up as the ideal Japanese family and tending to ignore any splits between them.[69] Their different attitudes towards both sumo philosophy and the outside world had been noted, with Takanohana being regarded as somewhat aloof and reserved and Wakanohana having a warmer personality.[69][70] However, upon their father's death from cancer on May 30, 2005, a bitter rift between the brothers was widely reported in the Japanese media.[69][71] Takanohana felt he should be the chief mourner at the funeral as he had remained in the Sumo Association whilst his brother had left to become a TV celebrity, but the role went to Wakanohana as the elder brother, as is traditional.[72] However, with their father reported to have left no will, it was suggested that the feud revolved around control of his estate.[73]

Takanohana also condemned his mother for her extramarital affair, which led to her divorce from his father and exit from the stable in July 2001, and had only been rumored up to that point.[74] She has now reverted to her old name of Noriko Fujita and published a book and appeared on TV, revealing details of life as a stablemaster's wife that are seldom heard outside the sumo world.[75] Takanohana has rarely spoken to her since.[76] In June 2008 he spoke of his distress at the news that she had been named as a defence witness in a civil lawsuit brought by the Sumo Association against the tabloid magazine Shūkan Gendai over allegations that his father benefited from a thrown match for the championship in 1975, saying, "she will essentially be fighting against me."[77] He said he would take responsibility by resigning from the Sumo Association if she took the stand. In a radio interview Fujita said she would not testify, saying, "I will not drag my child down".

Marriage

[edit]In late 1992 Takanohana announced his engagement to actress Rie Miyazawa, news which sparked a similar amount of coverage to the Japanese royal wedding held that year.[25] However the engagement was broken off the following year, reportedly because Miyazawa was seen by Takanohana's parents and the Sumo Association as being unwilling to sacrifice her career to become a regular stable wife.[25] The role of the wife of a head coach in looking after the stable's recruits and liaising with supporter's groups is regarded as a full-time job.[11] In May 1995 Takanohana married television announcer Keiko Kono, eight years older than him.[69] They have a son and two daughters.[78] His son Yuuichi is a shoemaker and radio personality who is married to the daughter of former sumo wrestler Fujinoshin.[79][80] It was reported in November 2018 that Takanohana and Kono had divorced.[81]

In September 2023, Takanohana's management office confirmed that he had married another woman in August 2023; the new spouse's identity was not disclosed.[82]

Career record

[edit]| Year | January Hatsu basho, Tokyo |

March Haru basho, Osaka |

May Natsu basho, Tokyo |

July Nagoya basho, Nagoya |

September Aki basho, Tokyo |

November Kyūshū basho, Fukuoka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | x | (Maezumo) | East Jonokuchi #11 5–2 |

West Jonidan #101 6–1 |

West Jonidan #31 6–1 |

East Sandanme #74 5–2 |

| 1989 | East Sandanme #41 5–2 |

West Sandanme #13 5–2 |

East Makushita #48 7–0 Champion |

East Makushita #6 3–4 |

West Makushita #9 7–0 Champion |

West Jūryō #10 8–7 |

| 1990 | West Jūryō #6 9–6 |

West Jūryō #3 9–6 |

East Maegashira #14 4–11 |

East Jūryō #5 8–7 |

East Jūryō #2 10–5 |

West Maegashira #12 8–7 |

| 1991 | West Maegashira #9 6–9 |

East Maegashira #13 12–3 TF |

West Maegashira #1 9–6 O★ |

West Komusubi #1 11–4 TO |

West Sekiwake #1 7–8 |

East Maegashira #1 7–8 |

| 1992 | East Maegashira #2 14–1 TOF |

West Sekiwake #1 5–10 |

West Maegashira #2 9–6 |

East Komusubi #2 8–7 |

West Komusubi #1 14–1 O |

West Sekiwake #1 10–5 |

| 1993 | East Sekiwake #1 11–4 |

East Ōzeki #1 11–4 |

East Ōzeki #1 14–1 |

East Ōzeki #1 13–2–P |

East Ōzeki #1 12–3 |

East Ōzeki #1 7–8 |

| 1994 | West Ōzeki #1 14–1 |

East Ōzeki #1 11–4 |

West Ōzeki #1 14–1 |

East Ōzeki #1 11–4 |

West Ōzeki #2 15–0 |

East Ōzeki #1 15–0 |

| 1995 | East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

West Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 12–3–P |

| 1996 | East Yokozuna #1 14–1–P |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 15–0 |

East Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

| 1997 | West Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 12–3–PP |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 14–1–P |

| 1998 | East Yokozuna #1 8–5–2 |

West Yokozuna #1 1–4–10 |

West Yokozuna #1 10–5 |

West Yokozuna #1 14–1 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

East Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

| 1999 | East Yokozuna #1 8–7 |

West Yokozuna #1 8–3–4 |

East Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #2 9–6 |

East Yokozuna #2 0–3–12 |

West Yokozuna #2 11–4 |

| 2000 | West Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

East Yokozuna #1 11–4 |

West Yokozuna #1 13–2 |

West Yokozuna #1 5–3–7 |

East Yokozuna #2 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

East Yokozuna #2 11–4 |

| 2001 | East Yokozuna #2 14–1–P |

East Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

East Yokozuna #1 13–2–P |

East Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

| 2002 | West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

West Yokozuna #1 12–3 |

West Yokozuna #1 Sat out due to injury 0–0–15 |

| 2003 | West Yokozuna #1 Retired 4–4–1 |

x | x | x | x | x |

| Record given as wins–losses–absences Top division champion Top division runner-up Retired Lower divisions Non-participation Sanshō key: F=Fighting spirit; O=Outstanding performance; T=Technique Also shown: ★=Kinboshi; P=Playoff(s) |

||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Injured Takanohana retires from sumo". Japan Times Online. 2003-01-21. Archived from the original on 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ^ a b c "Takanohana bouts by kimarite". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lewin, Brian (August 2005). "What will become of the dynasty?". Sumo Fan Magazine. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sharnoff, Lora (1993). Grand Sumo. Weatherhill. ISBN 0-8348-0283-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Panek, Mark (2006). Gaijin Yokozuna. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-3043-1.

- ^ Akamoto, Makiro (2000-10-27). "Scandals push sumo's grand family". Asahi Evening News. Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ a b c Newton, Clyde (1994). Dynamic Sumo. Kodansha. p. 124. ISBN 4-7700-1802-9.

- ^ Hall, Mina (1997). The Big Book of Sumo (Paperback). Berkeley, CA, USA: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 89. ISBN 1-880656-28-0.

- ^ Sterngold, James (1991-05-28). "Little Big Man Of Sumo Retires". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Kennedy, Gabrielle (2001-05-09). "Sumo's setting sun". Salon. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ a b Schilling, Mark (1994). Sumo: A Fan's Guide. Japan Times. ISBN 4-7890-0725-1.

- ^ a b "Farewell Takanohana:Record-Setting Sumo Grand Champion Retires". Trends in Japan. 2003-03-10. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ Vlastos, Stephen (1998). Mirror of Modernity:Invented Traditions in Modern Japan. University of California Press. p. 187. ISBN 0-520-20637-1.

- ^ Buckton, Mark (2007-05-27). "Hakuho wrestles his way into the history books". Japan Times. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ a b c "Takanohana Kōji Rikishi Information". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Takanohana bouts by basho". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ^ "Winter Olympics: Akebono to lead sumo's debut on Olympic stage". 1998-01-29. Archived from the original on 2007-12-28. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Sumo forced to wrestle with media pack". The Guardian. London. 1999-01-30. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Adams, Andy (2000-03-12). "Osaka to see yokozuna battle". Japan Times. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Newton, Cldye (2000-11-05). "Big guns head for Kyushu tourney". Japan Times. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ "Takanohana still star of the no-show". Japan Times. 12 May 2002. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Last hurrah for Takanohana?". Japan Times. 2002-09-08. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Maru overpowers Taka to take title". Japan Times. 2002-09-23. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ "Takanohana out again because of knee injury". Japan Times. 2002-11-09. Retrieved 2007-08-23.

- ^ a b c d e Watts, Jonathan (2003-01-21). "Sumo's star leaves the ring to darkness". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Gunning, John (4 April 2019). "Takanohana: The nail that sumo pounded down". Japan Times. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "A cut above". Japan Times. 2003-06-01. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Takanohana – goo Sumo". Japan Sumo Association. Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Perran, Thierry (April 2004). "Reflections on the world of sumo by Takanohana Oyakata". Le Monde Du Sumo. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ "Takanoiwa Yoshimori Rikishi Information".

- ^ "Takanohana-beya adds another recruit". Sumotalk. 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ "New Mongolian for Takanohana beya". Sumo Forum. 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ^ "New recruits for Hatsu 2009". Sumo Forum. 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ "Takakeisho Mitsunobu Rikishi Information". Sumo Reference. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Fureland, Gilles (March 2004). "Takanohana: new life, new challenges". Le Monde Du Sumo. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ 大相撲:貴乃花親方が役員待遇・審判部副部長に (in Japanese). Mainichi Shimbun. 2008-02-04. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ 【大相撲】スピード出世!貴乃花親方、35歳で役員待遇 (in Japanese). Sankei Sports. 2008-02-05. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ 貴乃花親方が審判部副部長に (in Japanese). Nikkan Sports. 2008-02-04. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ Gould, Chris (February 2010). "SFM Election Special Takanohana Controversially Joins Sumo's Board" (PDF). Sumo Fan Magazine. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ "Takanohana leaves Nishonoseki faction". Japan Times. 9 January 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ "Reformer Takanohana elected to sumo board". Japan Times. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ Parry, Richard Lloyd (28 January 2010). "Wrestler Takanohana takes on the Japanese sumo establishment". The Times. London. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ Hayashi, Yuka (1 February 2010). "Reformer wins a sumo board seat". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ "Takanohana group certified as ichimon". Nikkan Sports. 24 May 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Ex-star of sumo seen with mobster". Japan Times. 17 July 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ Buckton, Mark (27 August 2010). "Does a new Sumo Association boss signal a new direction?". Japan Times. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2011.

- ^ a b "Sumo body looks to demote stablemaster Takanohana over Harumafuji scandal". Japan Times. 28 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Takanohana wins Kodansha libel suit". Japan Times. 30 September 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ 貴親方公約2年以内にフルマラソン完走 (in Japanese). Nikkan Sports. 2007-11-09. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ^ "Sumo wrestles with history of violence outside the ring". Japan Times. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "貴乃花理事は巡業部長、相撲協会/デイリースポーツ online". デイリースポーツ online (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ a b "Sumo champion Harumafuji to be referred to prosecutors for alleged assault in drunken brawl". The Japan Times. 21 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "相撲協会の貴ノ岩聴取 貴乃花親方が拒否" (in Japanese). the Mainichi. 22 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Sumo gives governance in Japan another black eye". Nikkei Asian Review. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Seales, Rebecca (1 December 2017). "Inside the scandal-hit world of Japan's sumo wrestlers". BBC News. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Takanohana to cooperate with sumo association's probe into Harumafuji assault case". The Japan Times. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ "JSA to oust Takanohana as director over beating scandal". Asahi Shimbun. 28 December 2017. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Stablemaster Takanohana dismissed from post as director at Japan Sumo Association". Japan Times. 4 January 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Sumo elder Takanohana fails to regain director seat on JSA board". The Japan Times. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ "Takanohana stumbles badly in bid to shake up sumo world". Asahi Shimbun. 3 February 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- ^ "JSA demotes Takanohana again over 2nd assault incident". Asahi Shimbun. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ "貴乃花親方は審判部・指導普及部に配属 理事会 – 大相撲 : 日刊スポーツ". nikkansports.com (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- ^ "Takanohana resigns from JSA after lengthy controversies". Asahi Shimbun. 25 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ "Sumo boss Takanohana resigns over assault row". Yahoo News Singapore/AFP. 25 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "JSA denies putting pressure on Takanohana to clear its name". Asahi Shimbun. 26 September 2018. Archived from the original on 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "SUMO/ JSA approves Takanohana's retirement, transfer of stable". Asahi Shimbun. 1 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-10-03. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "貴乃花親方、退職金&功労金で約1000万円 芸能活動など「貴乃花」の使用は可能" (in Japanese). daily.co.jp. 2 October 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ "Former yokozuna Takanohana sets out to spread sumo worldwide". Asahi Shimbun. 19 May 2019. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Brasor, Philip (2005-06-16). "Takanohana vs. Wakanohana: The final faceoff". Japan Times. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ "Taka blasts Waka about inheritance". Japan Times. 2005-07-09. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ "Brotherly rift surfaces following funeral". Japan Times. 2005-06-04. Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ "Father's funeral fails to heal royal 'Waka-Taka' rift". Taipei Times. 2005-06-04. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Richard Lloyd Parry (2005-06-10). "No holds barred as warring brothers shock sumo world". The Times. London. Retrieved 2008-06-02.[dead link]

- ^ "Sumo's fairy tale family feud leaves brothers grim". Mainichi Daily News. 2005-06-18. Retrieved 2007-05-12.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Hanada Dynasty". Japan Omnibus. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ "Stablemaster's ex-wife tells all about Futagoyama stable". Japan Today. 2004-10-08. Retrieved 2008-06-02.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Takanohana's mother to testify against Kitanoumi Rijicho". Sumotalk. 2008-06-01. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ クローズアップ現代 放送記録 (in Japanese). NHK Online. January 2003. Archived from the original on 2005-09-06. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ^ "花田優一氏、結婚説や熱愛説を否定「彼女はいません。そんな暇はないです" (in Japanese). Sanspo. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "貴乃花親方の長男・花田優一さんが結婚 お相手は陣幕親方の娘" (in Japanese). Sponichi. 31 October 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Former stablemaster Takanohana, wife get divorced". Japan Times. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "元横綱貴乃花の花田光司氏が8月一般女性と再婚と文春オンライン マネジメント会社「事実です」" (in Japanese). Nikkan Sports. 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official biography of Takanohana Kōji at the Grand Sumo Homepage

Takanohana Kōji

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Entry into Sumo

Family Background and Influences

Takanohana Kōji, born Hanada Kōji, entered the world as the younger son of former ōzeki Takanohana Kenshi, a prominent sumo wrestler active during the 1970s who later assumed leadership of the Futagoyama stable. Kenshi's career, which included consistent top-division success and a reputation for technical prowess, directly shaped his sons' entry into the sport, as he coached them rigorously within the family-run stable environment.[5][6] His elder brother, Hanada Masaru—professionally known as Wakanohana III—likewise pursued sumo under their father's guidance, debuting in professional competition shortly before Kōji and eventually attaining yokozuna status in 1998. This fraternal partnership in the dohyō, marked by both collaboration and competition, amplified the Hanada family's visibility and contributed to a surge in sumo's domestic popularity during the 1990s, with the brothers collectively securing multiple tournament championships.[7][8] The pervasive family immersion in sumo traditions profoundly influenced Kōji's development, providing him with specialized training from adolescence; following victories in junior high school tournaments, he joined Futagoyama stable in March 1988 at age 15, absorbing his father's emphasis on explosive power and strategic footwork that became hallmarks of his own technique. This hereditary coaching dynamic, rooted in Kenshi's own experiences as a stablemaster, fostered an environment of high expectations and disciplined preparation, distinguishing Takanohana from peers without such lineage advantages.[5]Professional Debut and Initial Training

Takanohana Kōji, whose real name is Kōji Hanada, entered professional sumo at the age of 15, making his debut in the March 1988 tournament in the lowest jonokuchi division.[3] Alongside his older brother Wakanohana Kōji, he joined Futagoyama stable, a prominent heya known for producing top-division wrestlers.[4] Initial training in the stable emphasized building physical strength and discipline through daily regimens of weight training, rope pulling, and basic pushing exercises, supplemented by stable chores such as cleaning and meal preparation to instill hierarchy and endurance.[6] Futagoyama's environment, under its stablemaster, fostered rapid development for promising recruits like Takanohana, who quickly progressed from novice bouts, achieving his first kachi-koshi (majority wins) in subsequent tournaments.[2] By May 1990, after consistent advancements through the banzuke ranks, he entered the top makuuchi division, marking an accelerated early career trajectory.[2]Rise in Professional Sumo

Early Tournaments and Promotion to Makuuchi

Takanohana entered professional sumo at age 16, making his debut in mae-zumo—preparatory bouts for newcomers—during the March 1988 Hatsu tournament at Futagoyama stable.[9] His first competitive matches followed in the May 1988 Natsu tournament at the lowest jonokuchi division, ranked east #11, where he posted a solid 5-2 record to secure promotion.[9] Progressing swiftly through the lower divisions, Takanohana achieved kachi-koshi (eight or more wins in a 7-match tournament) in each of his initial jonidan appearances: 6-1 in Nagoya 1988 (west #101) and 6-1 in Aki 1988 (west #31).[9] He reached sandanme by Kyushu 1988 (east #74, 5-2), maintaining consistent majority wins in Hatsu 1989 (east #41, 5-2) and Haru 1989 (west #13, 5-2).[9] Entering makushita for Natsu 1989 at east #48, he captured the divisional yusho with a perfect 7-0 record, though a subsequent 3-4 make-koshi in Nagoya 1989 (east #6) briefly stalled momentum.[9] Rebounding strongly, Takanohana won his second makushita yusho in Aki 1989 (west #9, 7-0), earning promotion to the salaried sekitori ranks of juryo for Kyushu 1989 at west #10, where he recorded 8-7.[9] He solidified his status with back-to-back 9-6 performances in Hatsu 1990 (west #6) and Haru 1990 (west #3), culminating in elevation to makuuchi—the top division—for Natsu 1990 at maegashira #14 east.[9] This ascent from debut to makuuchi in just over two years reflected his technical prowess and physical advantages, including agility and power honed from amateur sumo experience.[9] However, his makuuchi debut proved challenging, yielding a 4-11 record amid adaptation to higher competition intensity.[9]| Basho | Division | Rank | Record |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natsu 1988 | Jonokuchi | Jk11e | 5-2 |

| Nagoya 1988 | Jonidan | Jd101w | 6-1 |

| Aki 1988 | Jonidan | Jd31w | 6-1 |

| Kyushu 1988 | Sandanme | Sd74e | 5-2 |

| Hatsu 1989 | Sandanme | Sd41e | 5-2 |

| Haru 1989 | Sandanme | Sd13w | 5-2 |

| Natsu 1989 | Makushita | Ms48e | 7-0 (Yusho) |

| Nagoya 1989 | Makushita | Ms6e | 3-4 |

| Aki 1989 | Makushita | Ms9w | 7-0 (Yusho) |

| Kyushu 1989 | Juryo | J10w | 8-7 |

| Hatsu 1990 | Juryo | J6w | 9-6 |

| Haru 1990 | Juryo | J3w | 9-6 |

| Natsu 1990 | Makuuchi | M14e | 4-11 |

Key Victories Leading to Ozeki

Takanohana's promotion to ozeki in March 1993 followed a rapid rise marked by breakthrough tournament victories and sustained high performance in the sanyaku divisions. After entering the top makuuchi division in May 1990 and reaching sanyaku ranks by July 1991, he established himself with a runner-up finish and special prizes in March 1991, achieving 12 wins at age 18.[10] His first makuuchi yusho came in the January 1992 Hatsu basho as maegashira 2 east, where he outperformed established rivals to claim the championship.[11] The September 1992 Aki basho provided his second yusho, further showcasing his aggressive oshi-zumo style and belt control against yokozuna and ozeki opponents. These championships, combined with 10 wins in the November 1992 Kyushu basho and 11 wins in the January 1993 Hatsu basho as sekiwake, resulted in 36 victories over three consecutive tournaments—exceeding the informal threshold of 33 wins required for ozeki promotion from sekiwake or komusubi.[12] [13] This cumulative dominance, achieved at age 20, underscored Takanohana's technical maturity and physical prowess, earning unanimous approval from the Japan Sumo Association for the rank despite his youth.[2]Promotion to Yokozuna and Peak Career

Yokozuna Promotion in 1994

Takanohana, competing as an ozeki, entered the Aki Basho of September 1994 having secured five makuuchi yusho previously, though none consecutively, which had delayed his consideration for yokozuna promotion despite his dominant performances.[10] The traditional criterion for elevation to yokozuna requires an ozeki to win two consecutive tournament championships, demonstrating sustained excellence at the sport's highest levels. In the Aki Basho, held from September 11 to 25, Takanohana achieved a zensho yusho, posting a perfect 15–0 record and claiming the Emperor's Cup, which positioned him one victory away from the requisite consecutive titles.[2] The subsequent Kyushu Basho, from November 13 to 27 in Fukuoka, provided the decisive opportunity. Takanohana maintained his undefeated streak, reaching the final day at 14–0, where he faced yokozuna Akebono in a bout that drew intense scrutiny due to its implications for promotion. Employing an uwatenage throw, Takanohana defeated Akebono to finish 15–0, securing his second straight zensho yusho and fulfilling the promotion standard with exceptional dominance—only the second ozeki in modern sumo history to achieve back-to-back perfect records.[14][2] This performance, marked by 30 consecutive wins across the two tournaments, underscored his technical prowess and mental resilience, overcoming earlier inconsistencies in maintaining streaks. The Japan Sumo Association announced Takanohana's promotion to yokozuna on December 12, 1994, making him the 65th holder of the rank at age 23, one of the youngest in the postwar era.[2] The decision reflected empirical assessment of his recent results rather than precedent alone, as prior yokozuna promotions had occasionally emphasized longevity over such rapid zensho achievements; Takanohana's case highlighted a shift toward rewarding peak form, though some traditionalists questioned the speed given his relative youth and prior non-consecutive titles.[15] He received his yokozuna license and prepared for his debut in the rank at the Hatsu Basho in January 1995, where he would perform the inaugural dohyo-iri ceremony.[2]Dominant Tournaments 1994–1997

Following his promotion to yokozuna in December 1994, Takanohana demonstrated exceptional dominance in sumo tournaments, securing multiple championships with high win percentages and perfect records in several basho. In the 1995 Hatsu basho (January), he claimed his first yusho as yokozuna with a 13-2 record, defeating rivals including Akebono in their bout on Day 14.[9] He followed this with victories in the Natsu (14-1) and Nagoya (13-2) tournaments, showcasing consistent oshi-zumo techniques to overpower opponents, and capped the year with a zensho yusho (15-0) in Aki, his second perfect tournament of that type.[2] Overall, Takanohana won 80 of 90 makuuchi bouts in 1995, outpacing all other top-division wrestlers.[2] In 1996, Takanohana maintained his supremacy despite an injury-forced withdrawal in Kyushu, winning yusho in Haru (14-1), Natsu (14-1), Nagoya (13-2), and Aki (15-0 zensho), the latter marking his fourth career perfect record.[9] His aggressive tachiai and versatility in yorikiri and nage techniques neutralized key challengers like Musashimaru and Wakanohana, his brother.[2] He amassed 70 wins in 75 bouts that year, reflecting superior physical conditioning and strategic adaptability.[2] The year 1997 saw Takanohana secure three yusho—in Haru (12-3), Nagoya (13-2), and Aki (13-2)—while posting runner-up finishes in Hatsu, Natsu, and Kyushu, with a total of 78 wins in 90 bouts.[9] His performance underscored a commanding presence atop the banzuke, often clinching decisive victories against ozeki-level opposition early in tournaments to build insurmountable leads.[2] Across 1994–1997, he captured 15 championships, including four zensho yusho, establishing a benchmark for yokozuna-era dominance through empirical superiority in bout outcomes and tournament consistency.[2]| Year | Yusho Won | Total Makuuchi Wins-Losses |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 4 | 80-10 |

| 1995 | 4 | 80-10 |

| 1996 | 4 | 70-5 |

| 1997 | 3 | 78-12 |

Championships and Rivalries 1998–2001

In July 1998, Takanohana captured the Nagoya basho championship with a 14–1 record, his 19th career yusho. In September, he won the Aki basho for his 20th title.[16] These successes came amid competition from yokozuna Musashimaru, who had claimed the Hatsu basho earlier that year, and his brother Wakanohana, elevated to yokozuna status after consecutive wins in March and May.[16] Injuries significantly limited Takanohana's participation and performance in 1999 and 2000, resulting in no further championships during those years despite occasional strong showings.[16] His rivalry with Musashimaru intensified as the latter dominated several tournaments, including multiple yusho, forcing Takanohana to adapt against the Samoan's powerful thrusting attacks and size advantage in their head-to-head bouts. Takanohana staged a comeback in 2001, defeating Musashimaru in a playoff on January 21 to win the Hatsu basho with a 13–2 record, securing his 21st yusho.[17] He repeated the feat in May's Natsu basho, again prevailing over Musashimaru in the playoff despite a severe knee injury sustained earlier in the tournament, for his record 22nd and final championship.[18] These playoff victories underscored the fierce yokozuna rivalry, characterized by Takanohana's technical versatility—employing throws and belt grips—against Musashimaru's explosive forward pressure, with their matches often deciding tournament outcomes.[17][18]Final Years and Injuries 2002–2003

In the aftermath of a severe right knee injury sustained during the Natsu basho on May 25, 2001, against Musōyama, where he damaged ligaments and the meniscus but still competed on the final day to secure the yusho, Takanohana missed seven consecutive tournaments due to persistent knee issues.[19][20] He made a limited comeback at the Aki basho in September 2002, entering as yokozuna but withdrawing early after exacerbating his knee condition, managing only a few bouts including a victory over the shin-ōzeki Asashōryū on day 9.[21][22] Entering the Hatsu basho in January 2003 on short notice after withdrawing from training, Takanohana aimed for another recovery but struggled with reduced mobility and power, posting losses to lower-ranked wrestlers such as maegashira Aminishiki on day 8.[23][24] A shoulder injury incurred during a bout on January 13 forced him to sit out days 9 and 10, after which he withdrew entirely, citing the cumulative toll of injuries that had eroded his competitive edge.[10][19] On January 21, 2003, at age 30, Takanohana announced his retirement, ending a career hampered by recurring orthopedic problems that began intensifying after 2001, including the chronic knee damage that limited his thrusting and pivoting techniques essential to his style.[19][24] Despite surgical interventions and rehabilitation efforts, medical assessments indicated insufficient recovery for sustained top-division competition, prompting the decision to prioritize long-term health over further attempts at return.[21][19]Fighting Style and Technical Analysis

Preferred Techniques and Strengths

Takanohana Kōji employed a yotsu-sumo style, emphasizing grappling techniques that involved securing the opponent's mawashi (belt) rather than oshi-sumo pushing or thrusting attacks. His preferred grip was migi-yotsu, positioning the right hand inside and the left hand outside the opponent's belt, which facilitated forceful drives and throws. Among his favored kimarite (winning techniques), yorikiri—a frontal belt force-out—dominated, often comprising the bulk of his victories due to his ability to maintain a deep hold and propel opponents backward with relentless pressure. He also regularly utilized uwatenage, an outer-arm belt throw, leveraging superior leverage and timing to upend larger rivals.[2] Despite his modest stature for a yokozuna—measuring 1.85 meters in height and typically weighing 115 kilograms during peak years—Takanohana's strengths included explosive acceleration from the tachiai (initial charge), exceptional core strength for belt work, and agile footwork that enabled quick pivots and directional changes. These attributes allowed him to overcome size disadvantages against heavier opponents, compensating through technical precision and mental intensity rather than brute force alone. His proficiency in sustaining yotsu grips under duress highlighted a rare combination of power and finesse, contributing to 22 top-division championships.[2]Adaptations and Weaknesses

Takanohana's preferred migi-yotsu grip and yori-kata thrusting style allowed for forceful advances once the mawashi was secured, but required quick tachiai initiations to avoid being pushed back by oshi-dominant opponents who denied belt access.[1][2] Recurring injuries, beginning with a back issue that sidelined him for the 1996 Aki basho after four consecutive yusho, prompted adaptations including intentional weight gain to enhance stability and absorb impacts, though this exacerbated joint strain and reduced mobility over time.[24] By 2000–2001, he withdrew from five tournaments due to cumulative physical breakdown, shifting toward more selective engagement and reliance on upper-body power via techniques like uwatenage rather than sustained forward pressure.[24] These changes preserved some competitive edge against familiar rivals but highlighted vulnerabilities to prolonged bouts or agile, distance-controlling rikishi, contributing to his early retirement at age 30 in 2003.[24]Retirement from Active Competition

Decision and Circumstances in 2003

In early January 2003, Takanohana entered the Hatsu basho, the first grand sumo tournament of the year held in Tokyo, making a late decision to compete despite ongoing recovery from a right knee injury sustained in the May 2001 Natsu basho.[19][10] This knee issue had previously aggravated during a bout against yokozuna Musashimaru in 2001, limiting his participation in subsequent tournaments and contributing to a decline in performance.[14] During the tournament, Takanohana suffered a shoulder injury in an early bout, causing him to miss two days of competition before returning.[25] Upon his return, he secured some victories but incurred successive losses, including defeats to Dejima and, on the eighth day, to fourth-ranked maegashira Aminishiki, which highlighted his diminished physical condition and inability to execute techniques effectively against lower-ranked opponents.[19][25] These results, compounded by the persistent knee pain and the fresh shoulder setback, underscored the cumulative toll of injuries that had plagued his career since 2001, preventing sustained high-level competition. On January 20, 2003, after the loss to Aminishiki—described as a decisive fourth bout following his injury-induced absence—Takanohana informed the Japan Sumo Association of his retirement at age 30, effectively withdrawing from the tournament and ending his active career after eight years as yokozuna and 22 tournament championships.[26][25] In a subsequent news conference, he expressed initial mixed feelings about the decision but stated he was at peace with it, satisfied with his achievements, including overcoming earlier career hurdles to reach the sport's pinnacle.[26] The retirement marked the end of an era for sumo, as Takanohana's persistent efforts to return despite evident physical limitations reflected his determination but also the realistic assessment that further competition risked permanent damage without competitive viability.[24]Post-Retirement Involvement in Sumo

Establishment and Management of Takanohana Stable

In January 2004, Takanohana Kōji assumed control of his family's Futagoyama stable amid his father Takanohana Kenshi's failing health, with the Japan Sumo Association approving the succession and renaming it Takanohana-beya effective that month.[27] The stable, located in Sumida ward, Tokyo, maintained its tradition of housing and training wrestlers under a single roof, adhering to sumo's communal heya system.[27] Takanohana Kōji managed the stable as Takanohana Oyakata for 14 years, focusing on instilling discipline and passing down techniques from his father's era, which emphasized power and precision in ozeki-level sumo.[6] During this period, the heya produced makunouchi-ranked wrestlers including Takarafuji, who achieved komusubi status in 2013, and Takanoiwa, who reached sekiwake in 2014, though the stable did not yield any new sanyaku promotions on the scale of its prior yokozuna alumni.[10] The stable operated until January 2018, when Takanohana Kōji resigned from the Japan Sumo Association amid board election failure and prior reporting disputes, leading to its closure and the transfer of remaining wrestlers to other stables such as Musashigawa-beya.[28]Coaching Philosophy and Stable Achievements

Takanohana's approach to coaching emphasized rigorous daily training regimens and a strong work ethic, encouraging wrestlers to exceed standard practices in pursuit of technical proficiency and mental resilience.[29] This philosophy reflected his own career success through skill and determination rather than sheer size, promoting self-reliance amid the hierarchical structure typical of sumo stables, where the oyakata served as the central authority figure.[10] Under Takanohana's leadership of Futagoyama stable (later renamed Takanohana-beya in September 2005), the ichimon produced several sekitori, with standout developments including Takakeisho, who joined in 2014, debuted in the top makuuchi division in January 2017, and reached komusubi by September 2018.[30] Takakeisho credited Takanohana's guidance for his foundational growth, winning his first top-division championship in November 2018 and earning promotion to ozeki in March 2019 after the stable's absorption into Chiganoura-beya following Takanohana's April 2018 resignation.[31] Similarly, Takanosho, entering the stable around the same period, advanced to sekiwake by May 2024, demonstrating the lasting impact of the training environment on post-stable careers.[32] The stable maintained a competitive presence until its closure, inheriting and nurturing talent that contributed to subsequent successes in affiliated groups.[33]Major Controversies

Takanoiwa Assault Incident and Reporting

On October 25, 2017, during a regional sumo tour in Tottori Prefecture, yokozuna Harumafuji assaulted maegashira-ranked wrestler Takanoiwa, a member of Takanohana's stable, following an argument over Takanoiwa's use of a mobile phone at a bar.[34] Harumafuji struck Takanoiwa multiple times with open hands, fists, and objects including a karaoke machine remote control, reportedly causing concussion, a fractured skull base, and other injuries that required hospitalization for several days.[35] [36] The Japan Sumo Association (JSA) investigation confirmed the violence but found no evidence of a beer bottle being used, contrary to initial media reports; Harumafuji admitted to the slaps and punches during police questioning.[37] Takanohana, as stablemaster, became aware of the assault shortly after it occurred, as Takanoiwa informed stable members and sought medical attention the following day.[38] Despite JSA regulations requiring immediate reporting of such incidents within the sumo community, Takanohana did not notify the association promptly; instead, he filed a report with local police on October 27, 2017, and informed the JSA only after media inquiries surfaced on November 13, 2017.[35] [39] Takanohana later stated he prioritized his wrestler's well-being and police involvement over internal JSA protocols, viewing the matter as a criminal assault rather than a sumo disciplinary issue.[38] The delayed reporting drew sharp criticism from the JSA, which argued it hindered timely investigation and undermined trust in stablemasters' oversight responsibilities.[35] Harumafuji retired on November 29, 2017, accepting blame for the assault, while Takanoiwa continued competing but faced ongoing scrutiny.[39] Takanohana was demoted from the JSA board of directors to a lower committee role on January 4, 2018, for failing to report the incident adequately, marking the first such penalty for a stablemaster in this context; a second demotion followed in September 2018 amid related governance disputes.[40] [41] This episode highlighted tensions between Takanohana's independent approach to stable management and JSA hierarchical norms, contributing to broader scrutiny of violence in sumo stables.[42]Resignation from Sumo Association in 2018

Takanohana Hanshi, the stablemaster of Takanohana stable, submitted his resignation from the Japan Sumo Association (JSA) on September 25, 2018, citing the need to ensure the continuity of his wrestlers' careers amid ongoing disputes with the governing body.[43] The decision followed the JSA's demand that he retract allegations made in a September 19 protest letter criticizing the association's handling of the 2017 Takanoiwa assault scandal, which he refused to do.[4] This scandal involved Takanoiwa Manabu, a wrestler under Takanohana's stable, who suffered a fractured cheekbone in a December 2017 brawl with junior stablemates during a training trip, an incident Takanohana initially failed to report promptly to the JSA, leading to his earlier penalties including a 10-month pay cut and dismissal from the JSA board in February 2018.[44][28] In his resignation statement, Takanohana emphasized that withdrawing the protest would contradict his principles, stating, "I decided to retire from the JSA this morning" to allow his stable's 14 wrestlers and staff to transfer to the Futagoyama stable under former yokozuna Futahaguro, thereby preserving their professional status as JSA rules prohibit wrestlers from competing without an active stablemaster.[43][4] The JSA accepted the resignation immediately, marking the end of Takanohana's 15-year tenure as a coach and administrator since his 2003 retirement from competition.[45] Prior tensions had escalated when Takanohana, in his initial scandal report, accused JSA executives of pressuring him to alter details of the assault, claims the association deemed unsubstantiated and which contributed to his demotion from ichimon (stable group) leadership earlier that year.[46] The resignation highlighted deep divisions within sumo's hierarchical structure, as Takanohana's stance positioned him against the JSA's authority, which had already sanctioned him for inadequate oversight of stable violence and delayed disclosure—issues stemming from a December 28, 2017, incident where the altercation occurred amid alcohol-fueled hazing.[44] JSA officials, including chairman Hakkaku, maintained that Takanohana's allegations lacked evidence and violated protocols, while supporters viewed his exit as a principled stand against perceived institutional opacity.[4] Following the move, Takanohana stable was effectively dissolved, with key wrestlers like Takayasu and Takarafuji relocating, though Takanoiwa himself had retired earlier in 2018 due to lingering injuries from the beating.[43] This event underscored ongoing debates about accountability and reform in sumo governance, with Takanohana later founding an independent organization to promote the sport outside JSA control.[46]Views on Sumo Governance and Reforms

Takanohana has positioned himself as an advocate for internal reforms within the Japan Sumo Association (JSA), emphasizing improved crisis management, transparency in scandal investigations, and a stronger focus on youth development. In the wake of the 2017 Takanoiwa assault incident in his stable, he criticized the JSA's handling of the matter, accusing the organization of improper conduct in its investigative process and failure to adequately address violence among wrestlers.[4] This led to his refusal to apologize for his initial report, as demanded by the JSA, culminating in his resignation on September 25, 2018, after the association deemed his accusations unfounded.[4] [46] During JSA board elections, Takanohana sought to influence governance directly. In February 2010, upon declaring his candidacy, he advocated for maintaining sumo's "spiritual backbone" while prioritizing the systematic training and elevation of young wrestlers to revitalize the sport's future.[47] He secured a board seat at that time but faced re-election challenges later, notably in January 2018, when he ran explicitly to communicate his proposed changes despite anticipating defeat, receiving only minimal support and failing to retain his position.[28] Post-resignation, Takanohana's departure underscored his broader dissatisfaction with the JSA's rigid hierarchical structure and resistance to accountability, as evidenced by his withdrawal from the association's ichimon (faction) and decision to dissolve his stable rather than comply with perceived internal politics.[46] He has since pursued independent initiatives to promote sumo culture, implying a view that governance reforms could enable greater flexibility and external engagement to sustain the sport's relevance amid declining domestic interest.[48]Family Dynamics and Disputes

Relationship with Brother Wakanohana

Takanohana Kōji and his elder brother Wakanohana Masaru, both yokozuna who dominated sumo in the 1990s, initially shared a close professional bond forged in their father's stable, rising together to create the "Waka-Taka Boom" that elevated the sport's popularity to unprecedented levels in Japan.[7][49] As sons of former ōzeki Takanohana Kenshi, they trained rigorously under his guidance from a young age, with Wakanohana debuting in 1988 and Takanohana following in the same year, their parallel ascents marked by intense sibling rivalry on the dohyo that drew massive public interest.[5] This competition, while fueling their successes—Wakanohana reaching yokozuna in 1998 and Takanohana in 1994—also sowed seeds of tension, as evidenced by their on-dohyo clashes that highlighted stylistic differences and personal stakes.[7] The brothers' relationship deteriorated publicly in the late 1990s, culminating in Takanohana's September 1998 accusation that Wakanohana had failed to master sumo's fundamentals, a rare breach of the sport's convention against wrestlers criticizing peers openly.[50] This outburst exacerbated underlying frictions, with reports of their rivalry extending beyond competition into personal animosity, including Wakanohana's earlier retirement in 2000 amid health issues and perceived pressure from Takanohana's dominance.[8] Tensions persisted post-retirement, as they jointly inherited their father's elder stock under the Futagoyama name following his death on June 2, 2005, but clashed over stable management and leadership.[51] The feud intensified after their father's funeral on June 4, 2005, which failed to reconcile them and instead amplified disputes over his estate, reportedly left without a will, leading to legal and familial rifts described in Japanese media as a "royal scandal."[51][8] The brothers ultimately split the Futagoyama stable, with Takanohana establishing his own Takanohana stable and Wakanohana taking a different elder name, reflecting irreconcilable differences in vision for sumo's future and personal legacies.[52] Rumors of deeper causes, including inheritance uncertainties and professional betrayals, circulated but lacked formal resolution, underscoring a breakdown rooted in competitive egos and unaddressed grievances.[53] As of 2024, the estrangement endures, with Wakanohana avoiding mention of Takanohana even in discussions of shared records, and no public reconciliation efforts reported, marking their bond as one of sumo's most enduring familial fractures.[54][55]Inheritance and Post-Father Disputes

Following the death of their father, former yokozuna Takanohana Kenshi (stablemaster Futagoyama), on May 30, 2005, from esophageal cancer after nearly two years of illness, Takanohana Kōji and his elder brother Wakanohana Kiyomasa engaged in a highly publicized dispute centered on funeral arrangements and estate control.[8][53] Takanohana Kōji, who had inherited the Futagoyama stable upon his 2003 retirement and renamed it Takanohana stable, insisted on serving as the chief mourner at the funeral, arguing that his ongoing role within the Japan Sumo Association as an active elder (oyakata) entitled him to represent the family's sumo legacy.[56][51] Wakanohana Kiyomasa, who had retired from sumo in 2000 and severed formal ties with the association by establishing an independent training facility, countered that tradition dictated the eldest son lead the rites.[56][53] The disagreement escalated dramatically at the funeral home, where the brothers reportedly argued for approximately five hours over access to their father's body, with Takanohana Kōji blocking entry until his position was acknowledged, before eventually relenting.[52][8] Wakanohana Kiyomasa ultimately performed the chief mourner duties on June 3, 2005, at a Tokyo ceremony attended by sumo officials and family.[51] This incident, widely covered in Japanese media, highlighted longstanding tensions exacerbated by Wakanohana's departure from organized sumo, which Takanohana viewed as abandonment of family tradition.[56][57] Compounding the funeral conflict, the absence of a will from Futagoyama fueled disputes over the estate, including control of assets tied to the family's sumo heritage.[8] Wakanohana Kiyomasa publicly relinquished his inheritance claims to Takanohana Kōji shortly after the funeral, a concession reportedly aimed at resolving the rift but which failed to prevent further acrimony.[54][58] Takanohana Kōji, however, escalated criticisms in media interviews, accusing his brother of exploiting the family name for personal ventures outside sumo and faulting their mother for enabling Wakanohana's decisions, statements that deepened the familial estrangement.[56][8] These events marked a public culmination of fraternal discord, with Takanohana prioritizing institutional loyalty to sumo governance over blood ties, though no formal legal proceedings over the estate were reported.[53][57]Personal Life

Marriage and Divorce

Takanohana Kōji, whose real name is Hanada Kōji, married television presenter Keiko Kono in 1995.[3] The couple raised three children together during their marriage.[3] The marriage ended in divorce in 2018, coinciding with Takanohana's resignation from the Japan Sumo Association amid controversies involving his stable.[59] [60] Public reports on the divorce were limited, with sources confirming the split but providing no detailed reasons.[60]Health and Lifestyle Post-Sumo

After retiring from active sumo competition in January 2003 due to persistent injuries including knee ligament damage and shoulder problems, Takanohana successfully shed significant weight, transitioning from his peak fighting mass of around 115 kg (253 lb) to a slimmer physique that mitigated common post-career health risks for former wrestlers such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular vulnerabilities associated with retained bulk.[61][24] No major health complications have been publicly reported in the years following his full departure from the Japan Sumo Association on September 25, 2018, after which he adopted a low-profile lifestyle focused on personal matters rather than sumo involvement.[4] In a December 2024 interview, the 52-year-old Takanohana described his sumo-era role as concluded, emphasizing reflection on past achievements while maintaining a playful demeanor off the dohyo, with no indications of ongoing physical decline.[62]Records, Achievements, and Legacy

Career Statistics and Honors

Takanohana Kōji debuted in professional sumo in March 1988 and retired in January 2003 after a career marked by exceptional dominance in the top division.[2] He was promoted to ōzeki in May 1993 and elevated to yokozuna in December 1994, becoming the 65th wrestler to hold sumo's highest rank, following two consecutive zenshō yūshō (perfect records) in Aki and Kyushu 1994.[2] During his 49 tournaments as yokozuna, he maintained a high level of performance despite recurring injuries, particularly to his knees.[2] His overall career record comprised 794 wins, 262 losses, and 201 absences, yielding a winning percentage of .752.[2] In the makuuchi division, where he competed extensively after rapid promotion from the jonokuchi division in under two years, Takanohana recorded 701 wins against 217 losses and 201 absences, for a .764 win rate.[2] As an ōzeki over 11 tournaments, his record was 137–28.[2] Takanohana secured 22 makuuchi championships (yūshō) between January 1992 and May 2001, placing sixth on the all-time list.[4] Notable among these were four zenshō yūshō: Aki 1994, Kyushu 1994, Aki 1995, and Aki 1996.[2] He also achieved a personal best of 30 consecutive victories and earned one kinboshi (defeating a yokozuna as a maegashira) along with four special prizes (sanshō) for outstanding performance.[2]| Record Category | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Total Championships | 22 yūshō |

| Perfect Tournaments | 4 zenshō yūshō |

| Consecutive Wins | 30 |

| Special Prizes | 4 sanshō |

| Gold Stars (Kinboshi) | 1 |