Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Teleoceras

View on Wikipedia

| Teleoceras | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen at the Natural History Museum of LA | |

| |

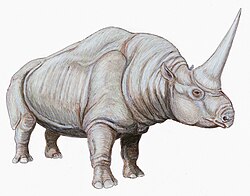

| 1913 T. fossiger illustration by Robert Bruce Horsfall. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Subfamily: | †Aceratheriinae |

| Genus: | †Teleoceras Hatcher, 1894 |

| Type species | |

| †Teleoceras major | |

| Species[1] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Teleoceras is an extinct genus of rhinocerotid endemic to North America during the Neogene (Miocene and Pliocene).

Taxonomy

[edit]Teleoceras is derived from Greek: "perfect" (teleos) & "horn" (keratos).[4]

Description

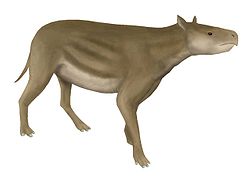

[edit]Teleoceras had much shorter legs than modern rhinos, and a barrel chest, making its build more like that of a hippopotamus than a modern rhino. It grew up to lengths of 13 feet (4.0 meters) long.[5] T. major was found to have been sexually dimorphic, with males being larger than females. Based on the most reliable method, non-length longbones, males could’ve weighed 883.3–1,109.7 kg (1,947–2,446 lb), while females were estimated to have weighed 785.1–840.1 kg (1,731–1,852 lb).[6]

Some species of Teleoceras have a small nasal horn, but this appears to be absent in other species such as T. aepysoma.[7]

Behavior and Paleoecology

[edit]Teleoceras has high crowned (hypsodont) molar teeth, which has historically led to suggestions that the species were grazers. Dental microwear and mesowear analysis alternatively suggest a browsing or mixed feeding (both browsing and grazing) diet.[8][9] Whether or not Teleoceras was semi-aquatic had been debated by experts. Based on this description, Henry Fairfield Osborn suggested in 1898 that it was semi-aquatic and hippo-like in habits, however and oxygen isotope analysis of tooth enamel suggests hippo-like grazing habits, but not aquatic.[6][10] However, δ18O measurements from Ashfall suggest that the species T. major was semi-aquatic.[11][12][13] Further evidence of the dependence on water of T. major comes from combined studies of its enamel 87Sr/86Sr, δ13C, and δ18O, which show its lifetime movement patterns were mostly restricted to areas with high water availability.[14]

Social behavior

[edit]Teleoceras was sexually dimorphic. Males were larger, with larger tusks (lower incisors), a more massive head and neck, and significantly larger forelimbs. As a result of bimaturism, females matured and stopped growing before males, which is often seen in extant polygynous mammals. Males may have fought for mating rights; healed wounds on skulls have been observed, and healed broken ribs are not uncommon (although not all have their sexes determined). This is further supported by the breeding age female-to-male ratio in the Ashfall Fossil Beds being 4.25:1. There is also a rarity of young adult males preserved at Ashfall, which may be accounted for if they formed bachelor herds away from females and dominant bulls.[6]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]Teleoceras was endemic to North America during the Miocene during the Hemingfordian faunal stage to the end of Hemphillian faunal stage from around 17.5 to 4.9 million years ago,[15][16] and is considered an index fauna of the Hemphillian.[17] However, several boundary / Blancan faunal stage specimens have been recovered from Pliocene era North America, including the Ringold Formation of Washington, the Beck Ranch fauna of Texas, the Pipe Creek sinkhole fauna of Indiana and the Saw Rock Canyon fauna of Kansas.[17][18]

The presence of Plionarctos and Teleoceras have been used to constrain the temporal ages of the Gray Fossil Site, Palmetto fauna and Pipe Creek Sinkhole to the Hemphillian (between 7Mya and 4.5Mya, late Miocene to early Pliocene),[19][20] however specimens of these index fossils younger than 4.5Mya put this temporal bracketing in doubt.[21]

Important sites

[edit]Ashfall Fossil Beds

[edit]Teleoceras major is the most common fossil in the Ashfall Fossil Beds of Nebraska. Over 100 intact T. major skeletons are preserved in ash from the Bruneau-Jarbidge supervolcanic eruption. Of the 20+ taxa present, T. major was buried above the rest, being the last of the animals to succumb (small animals died faster), several weeks or months after the pyroclastic airfall event. Their skeletons show evidence of bone disease, i.e. hypertrophic pulmonary osteodystrophy (HPOD), as a result of lung failure from the fine volcanic ash.[22]

Most of the skeletons are adult females and young, the breeding age female-to-male ratio being 4.25:1. There is also a rarity of young adult males. If the rhinos at Ashfall represent a herd, this may be accounted for if young adult males formed bachelor herds away from females and dominant bulls. The age demographic is very similar to that of modern hippo herds, as amongst the skeletons, 54% are immature, 30% are young adults, and 16% are older adults.[6]

The greatest concentration of Ashfall fossils is housed in a building called the "Rhino Barn", due to the prevalence of T. major skeletons at the site, of which most were preserved in a nearly complete state. One extraordinary specimen includes the remains of a Teleoceras calf trying to suckle from its mother.[23]

Gray Fossil Site

[edit]The Gray Fossil Site in northeast Tennessee, dated to 4.5-5 million years ago, hosts one of the latest-known populations of Teleoceras, Teleoceras aepysoma.[24]

Extinction

[edit]Teleoceras is typically though to have gone extinct in North America (alongside Aphelops) at the end of the Hemphillian, most likely due to rapid climate cooling, increased seasonality and expansion of C4 grasses, as isotopic evidence suggests that the uptake of C4 plants was far less than that in contemporary horses.[15] However, Blancan age specimens may be younger than 4.5 million years old, and may be as young as 3.5 million years old (although some sites are disputed).[17][18]

References

[edit]- ^ Prothero, 2005, p. 94.

- ^ McKenna & Bell, 1997, p. 483.

- ^ Prothero, 2005, p. 122.

- ^ "Glossary. American Museum of Natural History". Archived from the original on 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Region 4: The Great Plains". geology.teacherfriendlyguide.org. Retrieved 2021-06-26.

- ^ a b c d Mead, Alfred J. (2000). "Sexual dimorphism and paleoecology in Teleoceras, a North American Miocene rhinoceros". Paleobiology. 26 (4): 689–706. Bibcode:2000Pbio...26..689M. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0689:SDAPIT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ Short, Rachel; Wallace, Steven; Emmert, Laura (2019-04-27). "A new species of Teleoceras (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from the late Hemphillian of Tennessee". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 56 (5): 183–260. doi:10.58782/flmnh.kpcf8483. ISSN 2373-9991.

- ^ Mihlbachler, Matthew C.; Campbell, Daniel; Chen, Charlotte; Ayoub, Michael; Kaur, Pawandeep (February 2018). "Microwear–mesowear congruence and mortality bias in rhinoceros mass-death assemblages". Paleobiology. 44 (1): 131–154. Bibcode:2018Pbio...44..131M. doi:10.1017/pab.2017.13. ISSN 0094-8373. S2CID 90987376.

- ^ Voorhies, M. R.; Thomasson, J. R. (1979-10-19). "Fossil grass anthoecia within miocene rhinoceros skeletons: diet in an extinct species". Science. 206 (4416): 331–333. Bibcode:1979Sci...206..331V. doi:10.1126/science.206.4416.331. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17733681.

- ^ MacFadden, Bruce J. (1998). "Tale of two Rhinos: Isotopic Ecology, Paleodiet, and Niche Differentiation of Aphelops and Teloceras from the Florida Neogene". Paleobiology. 24 (2): 274–286. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(1998)024[0274:TOTRIE]2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2401243.

- ^ Ward, Clark T.; Crowley, Brooke E.; Secord, Ross (15 September 2024). "Home on the range: A multi-isotope investigation of ungulate resource partitioning at Ashfall Fossil Beds, Nebraska, USA". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 650 112375. Bibcode:2024PPP...65012375W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2024.112375.

- ^ "Fossil Teeth Of Extinct North American Rhinos Reveal An Aquatic Lifestyle Similar To Modern Hippos". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2025-02-23.

- ^ Wang, Bian; Secord, Ross (2020-03-15). "Paleoecology of Aphelops and Teleoceras (Rhinocerotidae) through an interval of changing climate and vegetation in the Neogene of the Great Plains, central United States". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 542 109411. Bibcode:2020PPP...54209411W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109411. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Ward, Clark T.; Crowley, Brooke E.; Secord, Ross (4 April 2025). "Enamel carbon, oxygen, and strontium isotopes reveal limited mobility in an extinct rhinoceros at Ashfall Fossil Beds, Nebraska, USA". Scientific Reports. 15 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-025-94263-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 11971351. PMID 40185810. Retrieved 10 August 2025 – via Springer Nature Link.

- ^ a b Wang, B.; Secord, R. (2020). "Paleoecology of Aphelops and Teleoceras (Rhinocerotidae) through an interval of changing climate and vegetation in the Neogene of the Great Plains, central United States". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 542 109411. Bibcode:2020PPP...54209411W. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.109411.

- ^ "The Evolution of North American Rhinoceroses". Cambridge University Press & Assessment. Retrieved 2025-07-16.

- ^ a b c Samuels, Joshua X.; Bredehoeft, Keila E.; Wallace, Steven C. (2018). "A new species of Gulo from the Early Pliocene Gray Fossil Site (Eastern United States); rethinking the evolution of wolverines". PeerJ. 6 e4648. doi:10.7717/peerj.4648. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5910791. PMID 29682423.

- ^ a b Gustafson, Eric P. (2012-05-01). "New records of rhinoceroses from the Ringold Formation of central Washington and the Hemphillian-Blancan boundary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (3): 727–731. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..727G. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.658481. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Hawkins, Patrick (2011-05-01). "Variation in the Modified First Metatarsal of a Large Sample of Tapirus polkensis and the Functional Implications for Ceratomorphs". Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- ^ Wallace, Steven C.; Wang, Xiaoming (30 September 2004). "Two new carnivores from an unusual late Tertiary forest biota in eastern North America" (PDF). Nature.

- ^ Samuels, Joshua X.; Bredehoeft, Keila E.; Wallace, Steven C. (2018). "A new species of Gulo from the Early Pliocene Gray Fossil Site (Eastern United States); rethinking the evolution of wolverines". PeerJ. 6 e4648. doi:10.7717/peerj.4648. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 5910791. PMID 29682423.

- ^ Tucker, S.T.; Otto, R.E.; Joeckel, R.M.; Voorhies, M.R. (April 2014), "The geology and paleontology of Ashfall Fossil Beds, a late Miocene (Clarendonian) mass-death assemblage, Antelope County and adjacent Knox County, Nebraska, USA", Geologic Field Trips along the Boundary between the Central Lowlands and Great Plains: 2014 Meeting of the GSA North-Central Section, Geological Society of America, pp. 1–22, doi:10.1130/2014.0036(01), ISBN 978-0-8137-0036-6, retrieved 2024-08-13

- ^ "Ashfall Fossil Beds". Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2005-12-13.

- ^ Short, Rachel A; Wallace, Steven C. "A New Species of Teleoceras (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from the Late Hemphillian of Tennessee".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Bibliography

[edit]- McKenna, Malcolm C., and Bell, Susan K. 1997. Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press, New York, 631 pp. ISBN 0-231-11013-8

- Prothero, Donald R. 2005. The Evolution of North American Rhinoceroses. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 218 pp. ISBN 0-521-83240-3

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Teleoceras at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Teleoceras at Wikimedia Commons

Teleoceras

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy

Etymology and Classification

The genus name Teleoceras derives from the Greek words telos, meaning "end," and keras, meaning "horn," alluding to the position of the nasal horn at the end of the nasals. It was established by paleontologist John Bell Hatcher in 1894, based on the type species T. major from Miocene deposits in the Loup Fork region of Nebraska.[5] (Note: Original paper in American Geologist, vol. 13, pp. 148-150; digitized at Biodiversity Heritage Library) Teleoceras belongs to the family Rhinocerotidae within the order Perissodactyla, specifically placed in the subfamily Aceratheriinae and tribe Teleoceratini. This tribe encompasses short-limbed, horned or hornless North American rhinocerotids adapted to grazing lifestyles. Closest relatives include the contemporaneous genus Aphelops, which shares similar brachycephalic skulls and graviportal limb adaptations, as well as Eurasian forms like Prosantorhinus and Brachypotherium, forming a monophyletic clade supported by synapomorphies such as reduced metapodials and robust postcranial elements. The genus evolved from early Miocene ancestors in the Aceratheriinae, representing a late radiation of immigrant rhinocerotids into North America during the Hemingfordian land-mammal age.[6][7] Historically, the taxonomy of Teleoceras has undergone revisions since its initial description from Nebraska quarries, where fragmentary skulls and postcrania revealed its distinctive short-legged morphology. Early proposed synonyms, such as Mesoceras (erected by Cook in 1930 for certain Miocene forms) and Paraphelops (proposed by Lane in 1927 for hornless variants), were later synonymized under Teleoceras through cladistic analyses that emphasized shared dental and cranial features like hypsodont molars and nasal bossing. These resolutions, detailed in comprehensive reviews, confirm Teleoceras as a valid, monophyletic genus encompassing multiple species across the late Miocene to early Pliocene.[7][8]Known Species

The genus Teleoceras encompasses at least 12 recognized species, primarily distinguished by variations in body size, limb proportions, horn morphology, and dental features such as hypsodonty and crown patterns on molars. These species span the late Miocene to early Pliocene across North America, with most known from the Great Plains but some extending to eastern and southern regions. The type species is T. major Hatcher, 1894, from the late Miocene (Clarendonian to Hemphillian) of the Great Plains, notable for its robust build, prominent paired nasal horns, and short, pillar-like limbs adapted for grazing in open grasslands.[9][10] Other species exhibit diversity in size and form, reflecting adaptations to changing environments. T. americanum (Yatkola and Tanner, 1979) is an early Hemphillian form from the central Great Plains, smaller than T. major with less pronounced nasal horns and more primitive dental morphology. T. fossiger Cope, 1878 dates to the Hemphillian of the High Plains, featuring a longer upper tooth row and moderately developed horns. T. guymonensis Prothero, 2005, from the late Hemphillian of Oklahoma, shows increased body size and thicker limb bones. T. hicksi (Lucas and Hatcher, 1902, emended Prothero, 2005) is known from Hemphillian sites in Texas, with diagnostic short tusks and broad zygomatic arches. T. medicornu (Osborn, 1904) from the Miocene of Nebraska displays exaggerated nasal horn development in males. T. minor Matthew, 1904, represents a smaller-bodied variant from the Clarendonian of the Great Plains, with reduced horn size. T. olsoni Voorhies, 1990, from late Miocene Nebraska localities, has distinctive cranial proportions and dental wear patterns indicating heavy grazing. T. proterum Leidy, 1885, an early Hemphillian species from Florida and the Gulf Coast, features prominent cingula on upper premolars and a less barrel-shaped torso. T. skinneri Voorhies and Corner, 1982, from the late Miocene of Nebraska, is similar to T. major but with finer dental crenulations. Additional recognized species include T. aginense, T. brachyrhinum, and T. meridianum, known from various Miocene localities in the Great Plains.[9][11][12] A recent addition to the genus is T. aepysoma Short, 2019, described from the late Hemphillian (ca. 4.5–4.9 Ma) Gray Fossil Site in eastern Tennessee, representing the easternmost known occurrence of Teleoceras. This species lacks nasal horns, has unfused nasals, pronounced supraorbital tubercles, and longer, more gracile forelimbs (e.g., humerus length up to 10% greater than in T. major), resulting in a higher-shouldered body less suited to amphibious lifestyles than western congeners. These traits challenge prior genus diagnoses emphasizing short limbs and horn presence, prompting revisions to the Teleoceratini tribe. Fossils include at least six individuals, highlighting an unexpected Appalachian distribution possibly linked to forested habitats.[10][13]| Species | Temporal Range | Geographic Range | Key Diagnostic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| T. major | Late Miocene (Clarendonian–Hemphillian) | Great Plains (e.g., Nebraska) | Prominent nasal horns, short robust limbs, hypsodont molars |

| T. americanum | Early Hemphillian | Central Great Plains | Smaller size, primitive dentition, reduced horns |

| T. aepysoma | Late Hemphillian | Eastern Tennessee | No nasal horns, longer forelimbs, elevated body |

Description

Body Structure

Teleoceras exhibited a distinctive morphology suggestive of adaptations to a semi-aquatic lifestyle, featuring a robust, barrel-shaped torso that provided buoyancy and stability in water, supported by short, pillar-like legs designed for wading rather than swift terrestrial movement.[3][14] The body reached lengths of up to 3.1 meters and a shoulder height of approximately 1.4 meters in larger species such as T. fossiger, with an estimated mass exceeding 1,700 kilograms, emphasizing its heavy, compact build.[15][16] The limbs of Teleoceras were characterized by dense, heavy bones, particularly in the metapodials, which offered enhanced structural support for bearing weight on soft, muddy substrates common in wetland environments.[17] Broad, laterally compressed foot bones further facilitated propulsion and stability in shallow waters or marshy terrains, distinguishing it from more cursorial relatives.[3] The skull was elongated with a broad nasal region, accommodating prominent horn bosses on the nasal and frontal bones in most species, which served as bases for keratinous horns used potentially in display or defense.[15] These features contributed to a low-slung head posture suited for foraging near water surfaces. Teleoceras possessed hypsodont (high-crowned) teeth suited for grazing on abrasive vegetation.[15] Unlike modern rhinoceroses, which possess longer limbs and higher-crowned dentition suited for arid grazing, Teleoceras displayed more amphibious traits, including its squat, hippo-like proportions that prioritized flotation and maneuverability in aquatic habitats over speed on dry land.[3][14]Sexual Dimorphism and Horns

Sexual dimorphism in Teleoceras major is pronounced in body size, with adult males estimated to have weighed between 880 and 1,110 kg, compared to 785–840 kg for females.[18] This size disparity, with a dimorphism ratio of 1.13–1.23, is evident in limb bone measurements such as the radius and femur cross-sectional areas, where males exhibit significantly larger dimensions (e.g., radius DR = 1.34).[19] The larger male body mass likely facilitated dominance displays and competition for mates in a polygynous mating system.[19] Horn morphology in Teleoceras varies across species but typically features paired nasal horns supported by rugose bosses on the unfused nasal bones, often accompanied by frontal bosses over the orbits.[3] These structures suggest roles in intraspecific interactions, though no significant sexual dimorphism has been documented in horn size itself.[19] An exception occurs in T. aepysoma, which lacks rugose bone on the nasals and thus has no nasal horns, while retaining pronounced supraorbital tubercles.[20] Evidence for sexual dimorphism derives from mass death assemblages at sites like Ashfall Fossil Beds, where skeletons show segregation by sex and age: abundant reproductive females, calves, and immature individuals, but few adult males and no subadults, indicating male-biased dispersal or exclusion from female groups.[21] Complementary isotopic analyses (δ¹³C, δ¹⁸O, and ⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) of enamel from 13 adult T. major individuals (five males, eight females) reveal no natal dispersal signatures in either sex, with all samples indicating local origins and limited mobility for both males and females.[21]Paleoecology

Diet and Habitat

Teleoceras species inhabited semi-aquatic environments across Miocene North America, favoring riverine, lacustrine, and swampy settings that supported a hygrophilous lifestyle.[22] This preference is inferred from their association with aquatic fauna, such as turtles and fish, in fossil assemblages, indicating proximity to standing water and wetland ecosystems.[4] Oxygen isotope analyses (δ¹⁸O) from tooth enamel further corroborate this, revealing lower and less variable values compared to fully terrestrial herbivores, consistent with regular access to freshwater sources.[22] The diet of Teleoceras was that of a mixed browser-grazer, incorporating both soft browse and tougher grasses in open-canopy habitats.[4] Carbon isotope data (δ¹³C) from enamel primarily indicate consumption of C₃ plants, such as dicotyledonous browse and C₃ grasses, with mean values around -8.4‰ to -8.5‰, though some late Miocene and Pliocene specimens show modest incorporation of C₄ grasses, as indicated by δ¹³C values up to around -7‰ suggesting mixed diets.[4][23][24] Their hypsodont molars, with high crowns and complex patterns, were adapted for processing abrasive vegetation, including siliceous grasses like Berriochloa species, as supported by dental microwear evidence.[22] Morphological adaptations reinforced this ecological niche, including a barrel-shaped body that aided buoyancy in water and short, stout limbs suited for wading through muddy or shallow aquatic environments.[4] These features, detailed in studies of body structure, parallel modern hippopotamuses in facilitating a semi-aquatic existence while foraging on wetland vegetation.[22] Recent paleoecological research, including 2025 isotopic investigations, confirms these traits enabled Teleoceras to thrive in moisture-dependent habitats amid shifting Neogene climates, with strontium isotope data (⁸⁷Sr/⁸⁶Sr) indicating limited mobility and home ranges under 50 km².[4]Social Behavior

Fossil evidence from mass death assemblages, such as the Ashfall Fossil Beds in Nebraska, indicates that Teleoceras lived in social groups, with over 100 articulated skeletons of T. major preserving a demographic profile of approximately 54% subadults and calves, 30% young adults, and 16% older adults, suggestive of mixed-sex herds similar to those of modern hippopotamuses.[25] These bone beds imply group living, potentially in herds of 10–20 individuals under typical conditions, though large gatherings at waterholes could involve dozens to hundreds, as evidenced by the catastrophic burial of a super-herd at Ashfall.[4] The breeding-age sex ratio of 4.25 females to 1 male further supports matriarchal or female-dominated groups with a single dominant male, possibly excluding young males to bachelor herds.[25] Male Teleoceras exhibited agonistic behaviors, including territorial fights, as demonstrated by healed injuries on skulls of T. major from the Ashfall Fossil Beds, such as puncture wounds on the frontal and nasal bones consistent with intrasexual combat using horns or tusks.[25] These pathologies, observed in specimens like UNSM 52272 and UNSM 27805, indicate repeated aggressive encounters among adult males vying for dominance or mating rights.[25] Reproductive behaviors in Teleoceras are inferred from sexual dimorphism and associated fossil evidence, with males significantly larger than females in nearly all skeletal measurements (e.g., body mass dimorphism ratio of 1.13–1.23), pointing to a polygynous system where dominant males monopolized access to multiple females.[25] Direct evidence of reproduction includes fetal remains preserved within a female T. major skeleton (UNSM 52373) from Ashfall, confirming gestation at the time of death.[25] While no neonatal fossils are directly associated, annual growth increments in male tusks, visible as rings and extending up to 22 years in T. proterum specimens, reflect prolonged development, and discrete tooth-wear patterns in T. major suggest seasonal breeding synchronized with environmental cues.[26][25]Fossil Sites

Ashfall Fossil Beds

The Ashfall Fossil Beds, located in Antelope County, northeastern Nebraska, represent a remarkable Late Miocene (approximately 12 million years ago) locality where a sudden volcanic ashfall preserved a diverse faunal assemblage in exceptional detail. The ash originated from a massive caldera-forming eruption in the Bruneau-Jarbidge volcanic field of southwestern Idaho, part of the Yellowstone hotspot track, which deposited a layer up to 60 cm thick over 1,000 miles away, rapidly entombing animals at a watering hole and preventing scavenger disturbance.[27][28] This taphonomic context has yielded over 100 articulated skeletons of Teleoceras major, primarily females and juveniles, indicating a large sedentary herd with limited mobility that was present at the site, succumbing to ash inhalation over days to weeks.[29][28][4] Key findings include well-preserved T. major specimens showing signs of mass mortality, with many individuals buried in life-like positions suggestive of herd dynamics, such as calves nestled against adults and a sex ratio implying harem structures (one mature male per several females), alongside evidence of male-biased dispersal and social grouping rather than seasonal migration. Evidence of bone pathologies, particularly hypertrophic osteopathy—a condition causing abnormal, frothy bone growth on limbs—is evident in rhinos, horses, and camels, resulting from prolonged lung damage due to volcanic ash inhalation, which likely exacerbated underlying respiratory issues like pneumonia. Associated fauna encompasses over 20 species, including five types of three-toed horses (Cormohipparion spp.), four camel species, cranes, turtles, tortoises, and a musk deer, all illustrating a mixed grassland-woodland ecosystem.[29][30][28] The site provides the strongest evidence for gregarious social behavior in Teleoceras, with the clustered skeletons and age distributions pointing to seasonal calving and group foraging in a local population. Recent 2024 isotopic analyses of tooth enamel from T. major and co-occurring ungulates confirm a diet dominated by C₃ grasses and plants in open habitats, with negligible C₄ grass consumption (<20%), aligning with 2025 multi-isotope studies (carbon, oxygen, strontium) indicating exclusive C₃ browsing/grazing adaptations, low dietary variability, and no long-distance movement, as preserved grass fragments in the rhinos' high-crowned teeth further support grazing in wet, C₃-dominated environments.[29][22][31][4]Gray Fossil Site

The Gray Fossil Site, situated in eastern Tennessee, represents a key late Hemphillian locality dating to approximately 4.5–5 million years ago, during the Hemphillian-Blancan transition.[32] This site originated as a paleosinkhole filled with lacustrine sediments, including rhythmites and lignite layers that preserve a diverse array of fossils alongside pollen records indicative of the local paleoenvironment.[10][33] The deposit's formation in a karstic sinkhole facilitated exceptional preservation of articulated skeletons, providing insights into a late Neogene ecosystem in the southern Appalachians.[34] In 2019, the species Teleoceras aepysoma was formally described from the site, with the holotype consisting of a nearly complete skull and articulated postcranial skeleton from an adult individual (ETMNH 601), notable for lacking rugose nasal bone texture typically associated with horn attachment.[13] Fossils represent a minimum of six individuals, including two nearly complete articulated skeletons, revealing T. aepysoma's distinctive morphology with elongated forelimb elements, elevated body posture, and pronounced supraorbital tubercles compared to western congeners.[13] A 2024 osteological study further examined these specimens, documenting pathologies such as healed rib fractures in ETMNH 601 (ribs 9–11), evidenced by fused callus formations spanning approximately 150 mm and indicating repeated trauma likely from intraspecific agonistic behavior; additional findings include healed avulsion fractures on the femur and innominate, as well as widespread rheumatoid arthritis in lower limb joints. The site's fauna is notably diverse, encompassing over 10,000 specimens from more than 60 species, including early red panda relatives such as Pristinailurus bristoli and other rhinocerotids alongside Teleoceras.[35] Associated vertebrates feature peccaries (Mylohyus elmorei, Prosthennops serus), wolverines (Gulo sp.), and helodermatid lizards, reflecting a mixed assemblage of browsing and carnivorous taxa.[13] These discoveries extend the known range of Teleoceras eastward into the Appalachian region, far from its typical Great Plains occurrences, and pollen evidence points to a cooler, forested habitat dominated by oak-hickory-pine assemblages rather than the open grasslands of western sites.[13][33] The pathologies observed in T. aepysoma specimens suggest physical stressors from dense terrain or social interactions in this highland refugium, highlighting adaptive challenges during late Miocene environmental shifts.Other Localities

Beyond the well-documented assemblages at the Ashfall Fossil Beds and Gray Fossil Site, fossils of Teleoceras have been recovered from numerous scattered localities across the central and western United States, highlighting its widespread distribution during the late Miocene to early Pliocene. In Nebraska, remains attributed to Teleoceras sp. occur in the Devil's Gulch Member of the Valentine Formation in Brown County, where fragmentary postcranial elements and dental material have been collected from quarry sites such as the Devil's Gulch Quarry.[36][37] In Texas, Teleoceras specimens, including T. hicksi and T. fossiger, are known from the Hemphill Formation in Hemphill County, particularly from sites like the White Knob locality and the Coffee Ranch quarry, yielding isolated teeth, limb bones, and partial skulls typical of Hemphillian-age deposits.[38][39][40] Further east in Florida, early species such as T. proterum and T. hicksi appear in the Bone Valley Formation, with abundant isolated teeth and postcranial fragments recovered from phosphate mines in central Florida, representing some of the easternmost records of the genus.[3][41][42] Scattered outcrops in Kansas and Colorado also preserve Teleoceras material, including T. fossiger and T. hicksi, primarily as isolated teeth and limb elements from Miocene-Pliocene sediments in the Great Plains region.[14][23][38] Notably, Blancan-age (approximately 3.5 million years ago) specimens from south-central Idaho, such as those in the Snake River Plain, include Teleoceras sp. remains like teeth and vertebrae, indicating potential late-surviving populations beyond the typical Hemphillian range.[43][44] These diverse localities demonstrate migratory patterns of Teleoceras from western origins toward eastern North America during the Neogene, with faunal correlations suggesting dispersal across the Great Plains.[45] Recent analyses, including those from 2012 onward, reaffirm Teleoceras as a key index fossil for the Hemphillian North American Land Mammal Age, though Pliocene records like those from Idaho extend its biochronological utility.[46][47]Extinction

Timeline and Range

Teleoceras first appeared during the late Hemingfordian North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA), approximately 17.5 million years ago (Ma) in the early Miocene.[48] The genus diversified and became widespread through the middle to late Miocene, reaching peak abundance in the Clarendonian (13.6–12.5 Ma) and Hemphillian (10.3–4.9 Ma) NALMAs.[15] Its temporal range extended to the late Hemphillian, with isolated records suggesting persistence into the early Blancan NALMA around 4.5 Ma.[46] Geographically, Teleoceras was endemic to North America, with the core of its distribution centered on the Great Plains, including abundant fossils from Nebraska, Kansas, South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Texas.[15] The range expanded eastward into Florida and the Appalachian region of Tennessee, as well as westward to the Pacific Northwest in Oregon and Washington, though occurrences west of the Rocky Mountains were relatively sparse; no fossils are known from Mexico.[3][10][46] In biostratigraphy, Teleoceras serves as a key index fossil for the Hemphillian NALMA, aiding in the correlation of late Miocene strata across the continent due to its consistent presence in well-sampled assemblages.[46] The genus's initial radiation aligns with the Mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (17–14.5 Ma), a global warming event that influenced North American terrestrial ecosystems.[48]Proposed Causes

The extinction of Teleoceras at the Miocene-Pliocene boundary is hypothesized to result from a combination of climatic and biotic pressures that progressively reduced suitable habitats and resources for this semi-aquatic rhinocerotid. A key factor was the onset of global cooling and aridification around 5 million years ago (Ma), which diminished wetlands and riverine environments essential for Teleoceras, as these rhinos relied on aquatic and riparian zones for thermoregulation and foraging.[49] This climate shift facilitated the widespread expansion of C₄ grasslands beginning approximately 6.5 Ma, documented through increasing δ¹³C values in paleosols and fossil tooth enamel across North America. Unlike many contemporaneous herbivores that adapted to graze C₄-dominated landscapes, Teleoceras enamel isotopes indicate it remained a predominantly C₃ browser with minimal C₄ incorporation (typically <20% of diet), leading to nutritional stress as preferred woody vegetation declined in favor of less digestible grasses.[49] Intensified biotic competition also contributed, as the diversification of equids such as Neohipparion and proboscideans like Cuvieronius during the late Hemphillian (ca. 6.9–4.9 Ma) likely outcompeted Teleoceras for water, browse, and space in increasingly open habitats. A 2020 stable isotope study highlights this dynamic through the synchronous decline and co-extinction of Teleoceras and Aphelops by around 4.9 Ma, suggesting shared vulnerabilities to faunal turnover.[49] Additional environmental stressors included heightened seasonality, which shortened growing periods and amplified resource scarcity for C₃-dependent species, alongside localized volcanic activity that may have disrupted ecosystems, though its broader impact on extinction remains unclear. No paleopathological or genetic evidence supports hyperdisease as a driver. Paleogeographic reconstructions reveal a gradual decline in Teleoceras abundance starting around 6.5 Ma, following its peak distribution in the late Miocene, rather than a sudden collapse.[49][50]References

- https://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Teleoceras