Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Torrefaction

View on Wikipedia

Torrefaction of biomass, e.g., wood or grain, is a mild form of pyrolysis at temperatures typically between 200 and 320 °C. Torrefaction changes biomass properties to provide a better fuel quality for combustion and gasification applications. Torrefaction produces a relatively dry product, which reduces or eliminates its potential for organic decomposition. Torrefaction combined with densification creates an energy-dense fuel carrier of 20 to 21 GJ/ton lower heating value (LHV).[1] Torrefaction causes the material to undergo Maillard reactions. Torrefied biomass can be used as an energy carrier or as a feedstock used in the production of bio-based fuels and chemicals.[2]

Biomass can be an important energy source.[3] However, there exists a large diversity of potential biomass sources, each with its own unique characteristics. To create efficient biomass-to-energy chains, torrefaction of biomass, combined with densification (pelletisation or briquetting), is a promising step towards overcoming the logistical challenges in developing large-scale sustainable energy solutions, by making it easier to transport and store. Pellets or briquettes have higher density, contain less moisture, and are more stable in storage than the biomass they are derived from.

Process

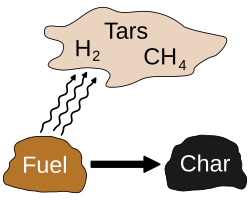

[edit]Torrefaction is a thermochemical treatment of biomass at 200 to 320 °C (392 to 608 °F). It is carried out under atmospheric pressure and in the absence of oxygen. During the torrefaction process, the water contained in the biomass as well as superfluous volatiles are released, and the biopolymers (cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin) partly decompose, giving off various types of volatiles.[4] The final product is the remaining solid, dry, blackened material[5] that is referred to as torrefied biomass or bio-coal.

During the process, the biomass typically loses 20% of its mass (bone dry basis) and 10% of its heating value, with no appreciable change in volume. This energy (the volatiles) can be used as a heating fuel for the torrefaction process. After the biomass is torrefied it can be densified, usually into briquettes or pellets using conventional densification equipment, to increase its mass and energy density and to improve its hydrophobic properties. The final product may repel water and thus can be stored in moist air or rain without appreciable change in moisture content or heating value, unlike the original biomass.

The history of torrefaction dates to the beginning of the 19th century, and gasifiers were used on a large scale during the Second World War.[6]

Added value of torrefied biomass

[edit]Torrefied and densified biomass has several advantages in different markets, which makes it a competitive option compared to conventional biomass wood pellets.

Higher energy density

[edit]An energy density of 18–20 GJ/m3 – compared to the 19–24 GJ/m3 heat content of natural anthracite coal – can be achieved when combined with densification (pelletizing or briquetting) compared to values of 10–11 GJ/m3 for raw biomass, driving a 40–50% reduction in transportation costs. Importantly, pelletizing or briquetting primarily increases energy density. Torrefaction alone typically decreases energy density, though it makes the material easier to make into pellets or briquettes.

More homogeneous composition

[edit]Torrefied biomass can be produced from a wide variety of raw biomass feedstocks that yield similar product properties. Most woody and herbaceous biomass consists of three main polymeric structures: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Together these are called lignocellulose. Torrefaction primarily drives moisture and oxygen-rich and hydrogen-rich functional groups from these structures, producing similar char-like structures in all three cases. Therefore, most biomass fuels, regardless of origin, produce torrefied products with similar properties – with the exception of ash properties, which largely reflect the original fuel ash content and composition.

Hydrophobic behavior

[edit]Torrefied biomass has hydrophobic properties, i.e., repels water, and when combined with densification make bulk storage in open air feasible.

Elimination of biological activity

[edit]All biological activity is stopped, reducing the risk of fire and stopping biological decomposition like rotting.

Improved grindability

[edit]Torrefaction of biomass leads to improved grindability of biomass.[7] This leads to more efficient co-firing in existing coal-fired power stations or entrained-flow gasification for the production of chemicals and transportation fuels.

Markets for torrefied biomass

[edit]Torrefied biomass has added value for different markets. Biomass in general provides a low-cost, low-risk route to lower CO2-emissions.[citation needed] When high volumes are needed, torrefaction can make biomass from distant sources price competitive because the denser material is easier to store and transport.

Wood powder fuel:

- Torrefied wood powder can be ground into a fine powder and when compressed, mimics liquefied petroleum gas (LPG).[citation needed]

Large-scale co-firing in coal-fired power plants:

- Torrefied biomass results in lower handling costs;

- Torrefied biomass enables higher co-firing rates;

- Product can be delivered in a range of LHVs (20–25 GJ/ton) and sizes (briquette, pellet).

- Co-firing torrefied biomass with coal leads to reduction in net power plant emissions.

Steel production:

- Fibrous biomass is very difficult to deploy in furnaces;

- To replace coal injection, biomass product needs to have LHV of more than 25 GJ/ton. Biochar can be added to the torrefied biomass to enhance the LHV.[8]

Residential/decentralized heating:

- Relatively high percentage of transport on wheels in the supply chain makes biomass expensive. Increasing volumetric energy density does decrease costs;

- Limited storage space increases need for increased volumetric density;

- Moisture content important as moisture leads to smoke and smell.

Biomass-to-Liquids:

- Torrefied biomass results in lower handling costs.

- Torrefied biomass serves as a 'clean' feedstock for production of transportation fuels (Fischer–Tropsch process), which saves on production costs.

Miscellaneous uses:

- Several guitar builders have used torrefaction to obtain more dimensionally stable wood for guitar parts than traditional kiln-drying or air-drying provides, including Yamaha, Martin, Gibson, and luthier Dana Bourgeois.[9][10]

See also

[edit]- Pyrolysis

- Thermally modified wood

- Carbonization

- Miscanthus giganteus § Transport and combustion challenges (contains a detailed description of the inferior combustion qualities of biomass compared to coal, and the positive effects of torrefaction.)

References

[edit]- ^ Austin, Anna (April 20, 2010). "French torrefaction firm targets North America". Biomass Power and Thermal. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Koukoulas, A.A. (2016). "Torrefaction: A Pathway Towards Fungible Biomass Feedstocks?" (PDF). Advanced Bioeconomy Feedstocks Conference.

- ^ Johnson, Robin (2007). "Torrefaction - A Warmer Solution to a Colder Climate". World Conservation and Wildlife Trust. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ^ Bates, R.B.; Ghoniem, A.F. (2012). "Biomass torrefaction: Modeling of volatile and solid product evolution kinetics" (PDF). Bioresource Technology. 124: 460–469. Bibcode:2012BiTec.124..460B. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.018. hdl:1721.1/103941. PMID 23026268.

- ^ "Torrefaction: The future of energy". Dutch Torrefaction Association (DTA). Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Torrefaction – A New Process In Biomass and Biofuels". New Energy and Fuel. November 19, 2008. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- ^ Thanapal, S.S.; Chen, W.; Annamalai, K.; Carlin, N.; Ansley, R.J.; Ranjan, D. (2014). "Carbon dioxide torrefaction of woody biomass". Energy & Fuels. 28 (2): 1147–1157. doi:10.1021/ef4022625.

- ^ Nallapaneni, Sasidhar (November 2025). "Retrofitting Blast Furnaces for Producing Green Steel and Green Urea" (PDF). Indian Journal of Environment Engineering. 5: 19–25. doi:10.54105/ijee.B1871.05021125. ISSN 2582-9289. Retrieved 21 November 2025.

- ^ Price, Huw. "ALL ABOUT... TORREFACTION". Guitar.com. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Administrator. "MARTIN - The Journal of Acoustic Guitars | C.F. Martin & Co". www.martinguitar.com. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

Further reading

[edit]- "Torrefied Wood Powder to Propane"; "About Us". Summerhill Biomass Systems, Inc. Retrieved February 29, 2012.

- Zwart, R.W.R.; "Torrefaction Quality Control based on logistic & end-user requirements", ECN report, ECN-L–11-107

- Verhoeff, F.; Adell, A.; Boersma, A.R.; Pels, J.R.; Lensselink, J.; Kiel, J.H.A.; Schukken, H.; "TorTech: Torrefaction as key Technology for the production of (solid) fuels from biomass and waste", ECN report, ECN-E–11-039

- Bergman, P.C.A.; Kiel, J.H.A., 2005, "Torrefaction for biomass upgrading", ECN report, ECN-RX–05-180

- Bergman, P.C.A.; Boersma, A.R.; Zwart, R.W.R.; Kiel, J.H.A., 2005, "Development of torrefaction for biomass co-firing in existing coal-fired power stations", ECN report, ECN-C–05-013

- Bergman, P.C.A., 2005, "Combined torrefaction and pelletisation – the TOP process", ECN Report, ECN-C–05-073

- Bergman, P.C.A.; Boersma, A.R.; Kiel, J.H.A.; Prins, M.J.; Ptasinski, K.J.; Janssen, F.G.G.J., 2005, "Torrefied biomass for entrained-flow gasification of biomass", ECN Report, ECN-C–05-026.

- Benchmarking the torrefaction process and product performance: Insights from the SteamBioAfrica project in Namibia

Torrefaction

View on GrokipediaDefinition and History

Definition

Torrefaction is a thermochemical pretreatment process involving the mild pyrolysis of biomass at temperatures between 200 and 300 °C in an inert or low-oxygen atmosphere, yielding a solid product known as torrefied biomass or biocoal. Biocoal is a stable, carbon-rich solid produced through the torrefaction of organic biomass in oxygen-free conditions, typically at temperatures between 250–350°C, converting feedstocks such as wood or agricultural residues into a charcoal-like material with high calorific value designed for energy production rather than soil amendment.[7][8][2][3] The main objective of torrefaction is to enhance the fuel properties of raw biomass, transforming it into a coal-like material by substantially lowering its moisture and volatile content while retaining much of its inherent energy.[1][9] This process typically results in a mass loss of 20–30%, attributed chiefly to the release of hemicellulose and volatiles, which produces a denser solid with an elevated calorific value compared to untreated biomass.[10][11] In contrast to full pyrolysis, which extensively decomposes biomass to generate char, liquids, and gases, torrefaction remains partial and regulated to prevent complete carbonization and preserve the majority of the solid yield.[1][8] The concept originated in the early 19th century with proposals and patents for processes producing "red charcoal" (charbon roux), with further development through late 19th-century patents.[12][13]Historical Development

The concept of torrefaction emerged in the early 19th century as a thermal treatment for wood to enhance its fuel properties and suitability for metallurgical applications, serving as an alternative to traditional charcoal. In 1835, French engineer Adéodat Dufournel proposed using torrefied wood in industrial processes, with implementation by Jean-Nicolas Houzeau-Muiron that same year, producing a material known as "red charcoal" (charbon roux) for its reddish hue and improved durability.[12] This innovation addressed wood preservation needs and fuel efficiency, leading to early patents: F.G. Echement secured one in Belgium in 1838 for torrefaction equipment installed at Chéhéry in 1839, followed by a French patent granted to Dupont and Dreyfus in 1839 for wood torrefaction and carbonization.[12] By the late 19th century, torrefaction had gained traction in France, Belgium, and Germany for limited commercial uses, with over 15 patents issued by 1952 reflecting ongoing interest in biomass upgrading.[14] During World War II, biomass thermal treatments and wood gasifiers saw scaled application in resource-constrained regions like Germany, where fuel shortages prompted their use to support synthetic fuel production and power vehicles and industry. Gasifiers, fueled by wood or pre-treated biomass to improve efficiency, were deployed on a large scale across Europe, with Germany producing nearly one million wood gasifier-powered vehicles by 1945 to circumvent petroleum embargoes.[15] While torrefaction-like processes were explored during this period, documentation of widespread torrefaction specifically remains limited compared to post-war developments, as such treatments aided in converting abundant wood into viable energy sources amid wartime exigencies.[16] The process experienced a revival in the 1970s and 1980s amid growing interest in renewable energy, with patents focusing on biomass upgrading for energy applications. In France, the company Pechiney operated a demonstration plant in the 1980s for metallurgical uses, producing thousands of tonnes annually and highlighting torrefaction's potential for high-value fuels.[14] This era saw renewed research emphasis, building on earlier patents to address logistical and combustion challenges in biomass utilization. Key advancements accelerated in the 2000s through institutions like the Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN), which initiated systematic studies in 2002–2003 to quantify torrefaction effects on diverse feedstocks, establishing process parameters for energy-efficient upgrading.[17] ECN's work, including a 50 kg/h pilot plant operational by 2008 and collaborations like the 2011 partnership with Andritz for reactor development, positioned torrefaction as a cornerstone for bioenergy integration.[15][17] Milestones in the 2010s included the launch of the first commercial pilot plants in Europe, driven by bioenergy policies promoting sustainable fuels. In the Netherlands, Topell Energy's 60,000 tonne/year facility using Torbed technology began operations in 2010, followed by Stramproy Green Investment's 45,000 tonne/year plant in 2011 and Torr-Coal's 35,000 tonne/year site in Belgium that same year.[18] North American efforts lagged slightly, with planned pilots like Integro Earth Fuels' facility in North Carolina targeting startup around 2010 but facing delays in financing.[18] These developments aligned with post-2010 policies, such as EU renewable energy directives, facilitating torrefaction's role in co-firing and biofuel supply chains, with initial transatlantic shipments occurring by 2012.[16][15] Following challenges in the mid-2010s, including closures of early plants like Topell's due to market and policy issues, torrefaction advanced with new commercial facilities by the 2020s. As of 2025, operational plants in Europe (e.g., via Perpetual Next/Torr-Coal technology), the US, and Asia (e.g., India) have contributed to growing global production, with the black pellets market valued at approximately $91 million in 2024 and projected to reach $735 million by 2030.[15][19]The Torrefaction Process

Mechanism and Chemistry

Torrefaction involves a series of thermochemical reactions that primarily target the structural components of lignocellulosic biomass, leading to the removal of oxygen and moisture while preserving much of the energy content in the solid residue, known as biocoal—a stable, carbon-rich solid designed for energy production rather than soil amendment.[20] The dominant process is the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose, which accounts for the majority of mass loss through deacetylation—where acetyl groups are cleaved to form acetic acid—and depolymerization, breaking the polysaccharide chains into smaller fragments. Cellulose undergoes partial degradation at higher severities, primarily through minor depolymerization and cross-linking, while lignin experiences limited breakdown, mainly via demethoxylation and condensation reactions that enhance its aromatic character. These chemical changes, occurring through partial decomposition in an inert atmosphere, result in a product with enhanced energy content due to increased carbon concentration and higher calorific value.[21][22][23] During these reactions, biomass releases a mixture of volatiles that constitute the non-solid fraction, including water vapor from initial dehydration, carbon monoxide (CO) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) from decarboxylation, acetic acid from deacetylation, and light hydrocarbons such as formaldehyde and methanol from fragmentation. These volatiles are produced in a roughly 30% yield by mass, with the remaining approximately 70% retained as a carbon-enriched solid char, or biocoal. A simplified representation of the hemicellulose decomposition is: hemicellulose → volatiles (e.g., H₂O, CO, CO₂, CH₃COOH) + char, where the char forms through secondary repolymerization of dehydrated units.[21][22] The chemistry unfolds across distinct thermal stages, beginning with drying below 100°C, where free and bound water is evaporated without significant structural change. This is followed by a pretreatment phase between 100°C and 200°C, involving initial hemicellulose hydrolysis and minor volatile evolution. The core torrefaction stage occurs at 250–350°C under an inert atmosphere, where reaction severity increases with temperature and residence time, promoting greater carbonization and oxygen removal as hemicellulose decomposition intensifies, yielding biocoal from feedstocks such as wood or agricultural residues.[21][22][20] These transformations fundamentally alter the biomass structure at the molecular level, breaking down the hydrophilic fibrous matrix of hemicellulose and cellulose into a more hydrophobic, brittle solid resembling coal. The elimination of the fiber saturation point—typically around 30% moisture in untreated biomass—occurs as hydroxyl groups are lost, reducing hygroscopicity and enabling the material to behave like a low-rank coal in subsequent handling.[21][22]Operational Parameters and Equipment

Torrefaction typically operates at temperatures between 200 and 300°C, with subdivisions into mild (200–235°C), medium (235–275°C), and severe (275–300°C) regimes depending on the desired biomass modification.[24][25][26] These temperatures facilitate the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose while minimizing cellulose and lignin degradation, requiring precise control to optimize energy yield.[24] Residence times vary from 5 to 60 minutes, though they can extend to several hours for larger particles or specific feedstocks, influencing the extent of mass loss and product uniformity.[24][25] Particle sizes generally range from 1 to 50 mm, as larger particles (e.g., up to 25 mm) promote higher solid yields but slower heat transfer and longer required residence times, while finer sizes (0.18–5 mm) accelerate the process.[25][26] The atmosphere is maintained inert, often using nitrogen (N₂) or carbon dioxide (CO₂), to prevent oxidative combustion and ensure controlled devolatilization.[24][25] Biomass feedstock is pre-dried to below 10–20% moisture content using integrated dryers before torrefaction, as excess water increases energy demands for evaporation.[24] Process configurations include batch systems, such as fixed-bed ovens suitable for laboratory-scale operations (kg/h throughput), and continuous systems like screw conveyors, rotary kilns, or moving-bed reactors for industrial scales (up to several tons/h).[24][26] Fluidized-bed reactors offer uniform heating via gas-solid contact, while rotary drums provide gentle agitation for larger particles; both types can integrate with downstream pelletizers.[25][26] Energy input is endothermic during startup, consuming 10–20% of the biomass's higher heating value (HHV), but the process becomes autothermal thereafter by combusting torrefaction gases (e.g., volatiles) for heat recovery.[24][25] Optimization relies on the torrefaction severity index (TSI), a combined metric of temperature and residence time (e.g., TSI = log₁₀(t × exp((T - T_ref)/14.75)), where t is time in minutes and T is temperature in °C), which balances mass yield (70–95%) against enhanced fuel properties.[24][25] Energy efficiency reaches approximately 90% through heat integration and gas recycling, minimizing external fuel needs after initial heating.[24][25] Heating rates (e.g., 5–20°C/min) and catalysts (e.g., alkali metals like K or Na) further refine outcomes, with slower rates favoring higher yields in continuous setups.[26]| Parameter | Typical Range | Influence on Process |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 200–300°C | Controls decomposition rate; higher values increase HHV but reduce yield.[24][25] |

| Residence Time | 5–60 min | Determines mass loss; longer times enhance uniformity for larger particles.[24][26] |

| Particle Size | 1–50 mm | Affects heat transfer; optimal for reactor design to avoid channeling.[25][26] |

| Atmosphere | Inert (N₂, CO₂) | Prevents oxidation; low-oxygen variants accelerate reactions.[24][25] |

| Energy Efficiency | ~90% | Achieved via gas combustion and heat recovery post-startup.[24][25] |