Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

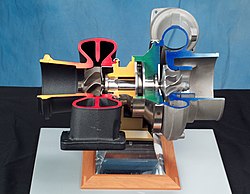

Turbocharger

View on Wikipedia

In an internal combustion engine, a turbocharger (also known as a turbo or a turbosupercharger) is a forced induction device that compresses the intake air, forcing more air into the engine in order to produce more power for a given displacement.[1][2]

Turbochargers are distinguished from superchargers in that a turbocharger is powered by the kinetic energy of the exhaust gases, whereas a supercharger is mechanically powered, usually by a belt from the engine's crankshaft.[3] However, up until the mid-20th century, a turbocharger was called a "turbosupercharger" and was considered a type of supercharger.[4]

History

[edit]Prior to the invention of the turbocharger, forced induction was only possible using mechanically-powered superchargers. Use of superchargers began in 1878, when several supercharged two-stroke gas engines were built using a design by Scottish engineer Dugald Clerk.[5] Then in 1885, Gottlieb Daimler patented the technique of using a gear-driven pump to force air into an internal combustion engine.[6]

The 1905 patent by Alfred Büchi, a Swiss engineer working at Sulzer is often considered the birth of the turbocharger.[7][8][9] This patent was for a compound radial engine with an exhaust-driven axial flow turbine and compressor mounted on a common shaft.[10][11] The first prototype was finished in 1915 with the aim of overcoming the power loss experienced by aircraft engines due to the decreased density of air at high altitudes.[12][13] However, the prototype was not reliable and did not reach production.[12] Another early patent for turbochargers was applied for in 1916 by French steam turbine inventor Auguste Rateau, for their intended use on the Renault engines used by French fighter planes.[10][14] Separately, testing in 1917 by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and Sanford Alexander Moss showed that a turbocharger could enable an engine to avoid any power loss (compared with the power produced at sea level) at an altitude of up to 4,250 m (13,944 ft) above sea level.[10] The testing was conducted at Pikes Peak in the United States using the Liberty L-12 aircraft engine.[14]

The first commercial application of a turbocharger was in June 1924 when the first heavy duty turbocharger, model VT402, was delivered from the Baden works of Brown, Boveri & Cie, under the supervision of Alfred Büchi, to SLM, Swiss Locomotive and Machine Works in Winterthur.[15] This was followed very closely in 1925, when Alfred Büchi successfully installed turbochargers on ten-cylinder diesel engines, increasing the power output from 1,300 to 1,860 kilowatts (1,750 to 2,500 hp).[16][17][18] This engine was used by the German Ministry of Transport for two large passenger ships called the Preussen and Hansestadt Danzig. The design was licensed to several manufacturers and turbochargers began to be used in marine, railcar and large stationary applications.[13]

Turbochargers were used on several aircraft engines during World War II, beginning with the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress in 1938, which used turbochargers produced by General Electric.[10][19] Other early turbocharged airplanes included the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and experimental variants of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190.

The first practical application for trucks was realized by Swiss truck manufacturing company Saurer in the 1930s. BXD and BZD engines were manufactured with optional turbocharging from 1931 onwards.[20] The Swiss industry played a pioneering role with turbocharging engines as witnessed by Sulzer, Saurer and Brown, Boveri & Cie.[21][22]

Automobile manufacturers began research into turbocharged engines during the 1950s; however, the problems of "turbo lag" and the bulky size of the turbocharger were not able to be solved at the time.[8][13] The first turbocharged cars were the short-lived Chevrolet Corvair Monza and the Oldsmobile Jetfire, both introduced in 1962.[23][24]

The turbo succeeded in motorsport, but took its time. The 1968 Indianapolis 500 was the first to be won with a turbocharged engine; turbos have won on the fast oval track ever since. Porsche pioneered turbos in engines derived from the 1963 Porsche 911, which had an air-cooled flat six engine just like the Chevrolet Corvair, but got turbocharged ten years later. Porsche 935 and Porsche 936 won both kinds of Sportcars World Championships in 1976, as well as the Le Mans 24h, proving that they could be reliable and fast. In Formula One, capacity was limited to only 1.5 litre, with the first race victories coming in the late 1970s, and the first F1 World Championship in 1983, with a BMW M10-based 4-cylinder engine that dates back to 1961.

Turbodiesel passenger cars appeared in the 1970s, with the Mercedes 300 D. Greater adoption of turbocharging in passenger cars began in the 1980s, as a way to increase the performance of smaller displacement engines.[10]

Design

[edit]

Like other forced induction devices, a compressor in the turbocharger pressurises the intake air before it enters the inlet manifold.[25] In the case of a turbocharger, the compressor is powered by the kinetic energy of the engine's exhaust gases, which is extracted by the turbocharger's turbine.[26][27]

The main components of the turbocharger are:

- Turbine – usually a radial turbine design

- Compressor – usually a centrifugal compressor

- Center housing hub rotating assembly

Turbine

[edit]

The turbine section (also called the "hot side" or "exhaust side" of the turbo) is where the rotational force is produced, in order to power the compressor (via a rotating shaft through the center of a turbo). After the exhaust has spun the turbine, it continues into the exhaust piping and out of the vehicle.

The turbine uses a series of blades to convert kinetic energy from the flow of exhaust gases to mechanical energy of a rotating shaft (which is used to power the compressor section). The turbine housings direct the gas flow through the turbine section, and the turbine itself can spin at speeds of up to 250,000 rpm.[28][29] Some turbocharger designs are available with multiple turbine housing options, allowing a housing to be selected to best suit the engine's characteristics and the performance requirements.

A turbocharger's performance is closely tied to its size,[30] and the relative sizes of the turbine wheel and the compressor wheel. Large turbines typically require higher exhaust gas flow rates, therefore increasing turbo lag and increasing the boost threshold. Small turbines can produce boost quickly and at lower flow rates, since it has lower rotational inertia, but can be a limiting factor in the peak power produced by the engine.[31][32] Various technologies, as described in the following sections, are often aimed at combining the benefits of both small turbines and large turbines.

Large diesel engines often use a single-stage axial inflow turbine instead of a radial turbine.[33]

Twin-scroll

[edit]A twin-scroll turbocharger uses two separate exhaust gas inlets, to make use of the pulses in the flow of the exhaust gasses from each cylinder.[34] In a standard (single-scroll) turbocharger, the exhaust gas from all cylinders is combined and enters the turbocharger via a single intake, which causes the gas pulses from each cylinder to interfere with each other. For a twin-scroll turbocharger, the cylinders are split into two groups in order to maximize the pulses. The exhaust manifold keeps the gases from these two groups of cylinders separated, then they travel through two separate spiral chambers ("scrolls") before entering the turbine housing via two separate nozzles. The scavenging effect of these gas pulses recovers more energy from the exhaust gases, minimizes parasitic back losses and improves responsiveness at low engine speeds.[35][36]

Another common feature of twin-scroll turbochargers is that the two nozzles are different sizes: the smaller nozzle is installed at a steeper angle and is used for low-rpm response, while the larger nozzle is less angled and optimised for times when high outputs are required.[37]

-

Cutaway view showing the two scrolls of a Mitsubishi twin-scroll (the larger scroll is illuminated in red)

-

Transparent exhaust manifold and turbo scrolls on a Hyundai Gamma engine, showing the paired cylinders (1 & 4 and 2 & 3)

Variable-geometry

[edit]

Variable-geometry turbochargers (also known as variable-nozzle turbochargers) are used to alter the effective aspect ratio of the turbocharger as operating conditions change. This is done with the use of adjustable vanes located inside the turbine housing between the inlet and turbine, which affect flow of gases towards the turbine. Some variable-geometry turbochargers use a rotary electric actuator to open and close the vanes,[38] while others use a pneumatic actuator.

If the turbine's aspect ratio is too large, the turbo will fail to create boost at low speeds; if the aspect ratio is too small, the turbo will choke the engine at high speeds, leading to high exhaust manifold pressures, high pumping losses, and ultimately lower power output. By altering the geometry of the turbine housing as the engine accelerates, the turbo's aspect ratio can be maintained at its optimum. Because of this, variable-geometry turbochargers often have reduced lag, a lower boost threshold, and greater efficiency at higher engine speeds.[30][31] The benefit of variable-geometry turbochargers is that the optimum aspect ratio at low engine speeds is very different from that at high engine speeds.

Electrically-assisted turbochargers

[edit]An electrically-assisted turbocharger combines a traditional exhaust-powered turbine with an electric motor, in order to reduce turbo lag. Recent advancements in electric turbocharger technology,[when?] such as mild hybrid integration,[39] have enabled turbochargers to start spooling before exhaust gases provide adequate pressure. This can further reduce turbo lag[40] and improve engine efficiency, especially during low-speed driving and frequent stop-and-go conditions seen in urban areas. This differs from an electric supercharger, which solely uses an electric motor to power the compressor.

Compressor

[edit]

The compressor draws in outside air through the engine's intake system, pressurises it, then feeds it into the combustion chambers (via the inlet manifold). The compressor section of the turbocharger consists of an impeller, a diffuser, and a volute housing. The operating characteristics of a compressor are described by the compressor map.

Ported shroud

[edit]Some turbochargers use a "ported shroud", whereby a ring of holes or circular grooves allows air to bleed around the compressor blades. Ported shroud designs can have greater resistance to compressor surge and can improve the efficiency of the compressor wheel.[41][42]

Center hub rotating assembly

[edit]The center housing rotating assembly (CHRA) houses the shaft that connects the turbine to the compressor. A lighter shaft can help reduce turbo lag.[43] The CHRA also contains a bearing to allow this shaft to rotate at high speeds with minimal friction.

Some CHRAs are water-cooled and have pipes for the engine's coolant to flow through. One reason for water cooling is to protect the turbocharger's lubricating oil from overheating.

Supporting components

[edit]

The simplest type of turbocharger is the free floating turbocharger.[44] This system would be able to achieve maximum boost at maximum engine revs and full throttle, however additional components are needed to produce an engine that is driveable in a range of load and rpm conditions.[44]

Additional components that are commonly used in conjunction with turbochargers are:

- Intercooler - a radiator used to cool the intake air after it has been pressurised by the turbocharger[45]

- Water injection - spraying water into the combustion chamber, in order to cool the intake air[46]

- Wastegate - many turbochargers are capable of producing boost pressures in some circumstances that are higher than the engine can safely withstand, therefore a wastegate is often used to limit the amount of exhaust gases that enter the turbine

- Blowoff valve - to prevent compressor stall when the throttle is closed

Turbo lag and boost threshold

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2022) |

Turbo lag refers to delay – when the engine rpm is within the turbocharger's operating range – that occurs between pressing the throttle and the turbocharger spooling up to provide boost pressure.[47][48] This delay is due to the increasing exhaust gas flow (after the throttle is suddenly opened) taking time to spin up the turbine to speeds where boost is produced.[49] The effect of turbo lag is reduced throttle response, in the form of a delay in the power delivery.[50] Superchargers do not suffer from turbo lag because the compressor mechanism is driven directly by the engine.

Methods to reduce turbo lag include:[citation needed]

- Lowering the rotational inertia of the turbocharger by using lower radius parts and ceramic and other lighter materials

- Changing the turbine's aspect ratio (A/R ratio)

- Increasing upper-deck air pressure (compressor discharge) and improving wastegate response

- Reducing bearing frictional losses, e.g., using a foil bearing rather than a conventional oil bearing

- Using variable-nozzle or twin-scroll turbochargers

- Decreasing the volume of the upper-deck piping

- Using multiple turbochargers sequentially or in parallel

- Using an antilag system

- Using a turbocharger spool valve to increase exhaust gas flow speed to the (twin-scroll) turbine

- Using a butterfly valve to force exhaust gas through a smaller passage in the turbo inlet

- Electric turbochargers[51] and hybrid turbochargers.

A similar phenomenon that is often mistaken for turbo lag is the boost threshold. This is where the engine speed (rpm) is currently below the operating range of the turbocharger system, therefore the engine is unable to produce significant boost. At low rpm, the exhaust gas flow rate is unable to spin the turbine sufficiently.

The boost threshold causes delays in the power delivery at low rpm (since the unboosted engine must accelerate the vehicle to increase the rpm above the boost threshold), while turbo lag causes delay in the power delivery at higher rpm.

Use of several turbochargers

[edit]Some engines use several turbochargers, usually to reduce turbo lag, increase the range of rpm where boost is produced, or simplify the layout of the intake/exhaust system. The most common arrangement is twin turbochargers, however triple-turbo or quad-turbo arrangements have been occasionally used in production cars.

Turbocharging versus supercharging

[edit]The key difference between a turbocharger and a supercharger is that a supercharger is mechanically driven by the engine (often through a belt connected to the crankshaft) whereas a turbocharger is powered by the kinetic energy of the engine's exhaust gas.[52] A turbocharger does not place a direct mechanical load on the engine, although turbochargers place exhaust back pressure on engines, increasing pumping losses.[52]

Supercharged engines are common in applications where throttle response is a key concern, and supercharged engines are less likely to heat soak the intake air.

Twincharging

[edit]A combination of an exhaust-driven turbocharger and an engine-driven supercharger can mitigate the weaknesses of both.[53] This technique is called twincharging.

Applications

[edit]

Turbochargers have been used in the following applications:

- Petrol-powered car engines

- Diesel-powered car and van engines

- Motorcycle engines (quite rarely)

- Diesel-powered truck engines, beginning with a Saurer truck in 1938[54]

- Bus and coach diesel engines

- Aircraft piston engines

- Marine engines

- Locomotive and diesel multiple unit engines for trains

- Stationary/industrial engines

In 2017, 27% of vehicles sold in the US were turbocharged.[55] In Europe 67% of all vehicles were turbocharged in 2014.[56] Historically, more than 90% of turbochargers were diesel, however, adoption in petrol engines is increasing.[57] The companies which manufacture the most turbochargers in Europe and the U.S. are Garrett Motion (formerly Honeywell), BorgWarner and Mitsubishi Turbocharger.[2][58][59]

Safety

[edit]Turbocharger failures and resultant high exhaust temperatures are among the causes of car fires.[60]

Failure of the seals will cause oil to leak into the exhaust system causing blue-gray smoke or a runaway diesel.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nice, Karim (4 December 2000). "How Turbochargers Work". Auto.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 26 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Automotive handbook (6th ed.). Stuttgart: Robert Bosch. 2004. p. 528. ISBN 0-8376-1243-8. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ "The Turbosupercharger and the Airplane Power Plant". Rwebs.net. 30 December 1943. Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- ^ Ian McNeil, ed. (1990). Encyclopedia of the History of Technology. London: Routledge. p. 315. ISBN 0-203-19211-7.

- ^ "History of the Supercharger". Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ "Celebrating 110 years of turbocharging". ABB. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b "The turbocharger turns 100 years old this week". www.newatlas.com. 18 November 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Vann, Peter (11 July 2004). Porsche Turbo: The Full History. MotorBooks International. ISBN 9780760319239.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, Jay K. (2008). Turbo: Real World High-Performance Turbocharger Systems. CarTech Inc. p. 9. ISBN 9781932494297. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ DE 204630 "Verbrennungskraftmaschinenanlage"

- ^ a b "Alfred Büchi the inventor of the turbocharger - page 1". www.ae-plus.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b c "Turbocharger History". www.cummins.ru. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Hill Climb". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Jenny, Ernst (1993). "The" BBC Turbocharger: A Swiss Success Story. Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 46.

- ^ "Alfred Büchi the inventor of the turbocharger - page 2". www.ae-plus.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017.

- ^ Compressor Performance: Aerodynamics for the User. M. Theodore Gresh. Newnes, 29 March 2001

- ^ Diesel and gas turbine progress, Volume 26. Diesel Engines, 1960

- ^ "World War II - General Electric Turbosupercharges". aviationshoppe.com.[dead link]

- ^ "Saurer Geschichte" (in German). German. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010.

- ^ Ernst Jenny: "Der BBC-Turbolader." Birkhäuser, Basel, 1993, ISBN 978-3-7643-2719-4. "Buchbesprechung." Neue Zürcher Zeitung, May 26, 1993, p. 69.

- ^ US 4838234 Mayer, Andreas: "Free-running pressure wave supercharger", issued 1989-07-13, assigned to BBC Brown Boveri AG, Baden, Switzerland

- ^ Culmer, Kris (8 March 2018). "Throwback Thursday 1962: the Oldsmobile Jetfire explained". Autocar. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "History". www.bwauto.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Variable-Geometry Turbochargers". Large.stanford.edu. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "Happy 100th Birthday to the Turbocharger - News - Automobile Magazine". www.MotorTrend.com. 21 December 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "How Turbo Chargers Work". Conceptengine.tripod.com. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Mechanical engineering: Volume 106, Issues 7-12; p.51

- ^ Popular Science. Detroit's big switch to Turbo Power. Apr 1984.

- ^ a b Veltman, Thomas (24 October 2010). "Variable-Geometry Turbochargers". Coursework for Physics 240. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ a b Tan, Paul (16 August 2006). "How does Variable Turbine Geometry work?". PaulTan.com. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ A National Maritime Academy Presentation. Variable Turbine Geometry.

- ^ Schobeiri, Meinhard T. (2012), Schobeiri, Meinhard T. (ed.), "Introduction, Turbomachinery, Applications, Types", Turbomachinery Flow Physics and Dynamic Performance, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 3–14, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-24675-3_1, ISBN 978-3-642-24675-3, retrieved 13 December 2024

- ^ "Twin-Turbocharging: How Does It Work?". www.CarThrottle.com. 11 October 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "A Look At Twin Scroll Turbo System Design - Divide And Conquer?". www.MotorTrend.com. 20 May 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Pratte, David. "Twin Scroll Turbo System Design". Modified Magazine. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "BorgWarner's Twin Scroll Turbocharger Delivers Power and Response for Premium Manufacturers - BorgWarner". www.borgwarner.com. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Hartman, Jeff (2007). Turbocharging Performance Handbook. MotorBooks International. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-61059-231-4.

- ^ "What is an electric turbocharger?". Mitsubishi Turbocharger. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2024.

- ^ Truett, Richard, and Jens Meiners. “Electric Turbocharger Eliminates Lag, Valeo Says.” Automotive News, vol. 88, no. 6632, p. 34.

- ^ "Ported Shroud Conversions". www.turbodynamics.co.uk. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ "GTW3684R". www.GarrettMotion.com. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ Nice, Karim. "How Turbochargers Work". Auto.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ a b "How Turbocharged Piston Engines Work". TurboKart.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "How a Turbocharger Works". www.GarrettMotion.com. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ Gearhart, Mark (22 July 2011). "Get Schooled: Water Methanol Injection 101". Dragzine.

- ^ "What Is Turbo Lag? And How Do You Get Rid Of It?". www.MotorTrend.com. 7 March 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "Turbo Lag. Reasons For Turbocharger Lag. How To Fix Turbo Lag". www.CarBuzz.com. 25 September 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "What is turbo lag?". www.enginebasics.com. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "5 Ways To Reduce Turbo Lag". www.CarThrottle.com. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Parkhurst, Terry (10 November 2006). "Turbochargers: an interview with Garrett's Martin Verschoor". Allpar. Archived from the original on 21 November 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- ^ a b "What is the difference between a turbocharger and a supercharger on a car's engine?". HowStuffWorks. 1 April 2000. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "How to twincharge an engine". Torquecars.com. 29 March 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ "BorgWarner turbo history". Turbodriven.com. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ "Turbo Engine Use at Record High". Wards Auto. 7 August 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ "Honeywell sees hot turbo growth ahead". Automotive News. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ^ Kahl, Martin (3 November 2010). "Interview: David Paja, VP, Global Marketing and Craig Balis, VP, Engineering Honeywell Turbo" (PDF). Automotive World. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Kitamura, Makiko (24 July 2008). "IHI Aims to Double Turbocharger Sales by 2013 on Europe Demand". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ CLEPA CEO Lars Holmqvist is retiring (18 November 2002). "Turbochargers - European growth driven by spread to small cars". Just-auto.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ Hart, Peter (November 2006). "Why trucks catch fire" (PDF). Australia: ARTSA Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2025.