Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turkish alphabet

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

| Turkish alphabet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Period | 1928 – present |

| Languages | Turkish |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Azerbaijani alphabet Crimean Tatar alphabet Gagauz alphabet Kalmyk Latin alphabet Tatar Latin alphabet Turkmen alphabet |

| Unicode | |

| subset of Latin (U+0000...U+024F) | |

The Turkish alphabet (Turkish: Türk alfabesi or Türk abecesi) is a Latin-script alphabet used for writing the Turkish language, consisting of 29 letters, seven of which (Ç, Ğ, I, İ, Ö, Ş and Ü) have been modified from their Latin originals for the phonetic requirements of the language. This alphabet represents modern Turkish pronunciation with a high degree of accuracy and specificity.[1] Mandated in 1928 as part of Atatürk's Reforms, it is the current official alphabet and the latest in a series of distinct alphabets used in different eras.

The Turkish alphabet has been the model for the official Latinization of several Turkic languages formerly written in the Arabic or Cyrillic script like Azerbaijani (1991),[2] Turkmen (1993),[3] and recently Kazakh (2021).[4]

Letters

[edit]The following table presents the Turkish letters, the sounds they correspond to in International Phonetic Alphabet and how these can be approximated more or less by an English speaker.

| Uppercase | Lowercase | Name | Name (IPA) | Value | English approximation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | a | /aː/ | /a/ | As a in father |

| B | b | be | /beː/ | /b/ | As b in boy |

| C | c | ce | /d͡ʒeː/ | /d͡ʒ/ | As j in joy |

| Ç | ç | çe | /t͡ʃeː/ | /t͡ʃ/ | As ch in chair |

| D | d | de | /deː/ | /d/ | As d in dog |

| E | e | e | /eː/ | /e/[a] | As e in red |

| F | f | fe | /feː/ | /f/ | As f in far |

| G | g | ge | /ɟeː/ | /ɡ/, /ɟ/[b] | As g in garage |

| Ğ | ğ | yumuşak ge | /jumuˈʃak ɟeː/ | [ː], [.], [j] (/ɰ/)[c] | — |

| H | h | he, ha, haş[d] | /heː/, /haː/ | /h/ | As h in hot |

| I | ı | ı | /ɯː/ | /ɯ/ | Close back unrounded vowel, like ㅡ eu in Korean 강릉 Gangneung Similar to o in ballot to a Turkish speaker's ears |

| İ | i | i | /iː/ | /i/ | As ee in cheese |

| J | j | je | /ʒeː/ | /ʒ/[e] | As s in measure |

| K | k | ke, ka[d] | /ceː/, /kaː/ | /c/, /k/[b] | As k in keen Similar to k in kit |

| L | l | le | /leː/ | /ɫ/, /l/[b] | As l in love |

| M | m | me | /meː/ | /m/ | As m in make |

| N | n | ne | /neː/ | /n/ | As n in nice |

| O | o | o | /oː/ | /o/ | As o in more |

| Ö | ö | ö | /œː/ | /œ/ | Open-mid front rounded vowel, like eu in French jeune Similar to u in nurse, with lips rounded |

| P | p | pe | /peː/ | /p/ | As p in pin |

| R | r | re | /ɾeː/ | /ɾ/ | As tt in American English better[f] |

| S | s | se | /seː/ | /s/ | As s in song |

| Ş | ş | şe | /ʃeː/ | /ʃ/ | As sh in show |

| T | t | te | /teː/ | /t/ | As t in tick |

| U | u | u | /uː/ | /u/ | As oo in tool |

| Ü | ü | ü | /yː/ | /y/ | Close front rounded vowel, like u in French tu Similar to u in cute |

| V | v | ve | /veː/ | /v/ | As v in vat |

| Y | y | ye | /jeː/ | /j/ | As y in yes |

| Z | z | ze | /zeː/ | /z/ | As z in zigzag |

| Q[g] | q | kû, kü[g] | /cuː/, /cyː/ | — | — |

| W[g] | w | çift ve, double u[g] | /t͡ʃift veː/ | — | — |

| X[g] | x | iks[g] | /iks/[b] | — | — |

- ^ /e/ is realised as [ɛ]~[æ] before coda /m, n, l, r/. E.g. gelmek [ɟɛlˈmec].

- ^ a b c d In native Turkic words, the velar consonants /k, ɡ/ are palatalised to [c, ɟ] when adjacent to the front vowels /e, i, œ, y/. Similarly, the consonant /l/ is realised as a clear or light [l] next to front vowels (including word finally), and as a velarised [ɫ] next to the central and back vowels /a, ɯ, o, u/. These alternations are not indicated orthographically: the same letters ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, and ⟨l⟩ are used for both pronunciations. In foreign borrowings and proper nouns, however, these distinct realisations of /k, ɡ, l/ are contrastive. In particular, [c, ɟ] and clear [l] are sometimes found in conjunction with the vowels [a] and [u]. This pronunciation can be indicated by adding a circumflex accent over the vowel: e.g. gâvur ('infidel'), mahkûm ('condemned'), lâzım ('necessary'), although this diacritic's usage has been increasingly archaic.

- ^ (1) Syllable initially: Silent, indicates a syllable break. That is Erdoğan [ˈɛɾ.do.an] (the English equivalent is approximately a W, i.e. "Erdowan") and değil [ˈde.il] (the English equivalent is approximately a Y, i.e. "deyil"). (2) Syllable finally after /e/: [j]. E.g. eğri [ej.ˈɾi]. (3) In other cases: Lengthening of the preceding vowel. E.g. bağ [ˈbaː]. (4) There is also a rare, dialectal occurrence of [ɰ], in Eastern and lower Ankara dialects.

- ^ a b The letters h and k are sometimes named haş, ha and ka (as in German), especially in acronyms, such as CHP, KKTC and TSK, and also in chemical formulas, as in H2O. However, the Turkish Language Association advises against this usage.[5]

- ^ The letter J represents the sound /ʒ/, which only occurs in loanwords (e.g. jilet).[6]

- ^ The alveolar tap /ɾ/ does not exist as a separate phoneme in English, though a similar sound appears in words like butter in a number of dialects.

- ^ a b c d e f The letters I, Q, W, and X of the ISO basic Latin alphabet do not occur in native Turkish words and nativised loanwords and are normally not considered to be letters of the Turkish alphabet (replacements for these letters are İ, K, V and KS). However, these letters are increasingly used in more recent loanwords and derivations thereof such as tweetlemek and proper names like Washington. I is generally considered a foreign allograph of İ that is used only in borrowings. Q and X have commonly accepted Turkish names, while W is usually referred to by its English name double u, its French name double vé, or rarely the Turkish calque of the latter, çift ve, which is recommended by Turkish Language Association.

Of the 29 letters, eight are vowels (A, E, I, İ, O, Ö, U, Ü); the other 21 are consonants.

Dotted and dotless I are distinct letters in Turkish such that ⟨i⟩ becomes ⟨İ⟩ when capitalised, ⟨I⟩ being the capital form of ⟨ı⟩.

Turkish also adds a circumflex over the back vowels ⟨â⟩ and ⟨û⟩ following ⟨k⟩, ⟨g⟩, or ⟨l⟩ when these consonants represent /c/, /ɟ/, and /l/ (instead of /k/, /ɡ/, and /ɫ/):

- â for /aː/ and/or to indicate that the consonant before â is palatalised; e.g. kâr /caɾ/ means "profit", while kar /kaɾ/ means "snow".

- î for /iː/ (no palatalisation implied, however lengthens the pronunciation of the vowel).

- û for /uː/ and/or to indicate palatalisation.

In the case of length distinction, these letters are used for old Arabic and Persian borrowings from the Ottoman Turkish period, most of which have been eliminated from the language. Native Turkish words have no vowel length distinction. The combinations of /c/, /ɟ/, and /l/ with /a/ and /u/ also mainly occur in loanwords, but may also occur in native Turkish compound words, as in the name Dilâçar (from dil + açar).

Turkish orthography is highly regular and a word's pronunciation is usually identified by its spelling.

Distinctive features

[edit]Dotted and dotless I are separate letters, each with its own uppercase and lowercase forms. The lowercase form of I is ı, and the lowercase form of İ is i. (In the original law establishing the alphabet, the dotted İ came before the undotted I; now their places are reversed.)[7] The letter J, however, uses a tittle in the same way English does, with a dotted lowercase version, and a dotless uppercase version.

Optional circumflex accents can be used with "â", "î" and "û" to disambiguate words with different meanings but otherwise the same spelling, or to indicate palatalisation of a preceding consonant (for example, while kar /kaɾ/ means "snow", kâr /caɾ/ means "profit"), or long vowels in loanwords, particularly from Arabic.

Software localisation

[edit]In software development, the Turkish alphabet is known for requiring special logic, particularly due to the varieties of i and their lowercase and uppercase versions.[8] This has been called the Turkish-I problem.[9]

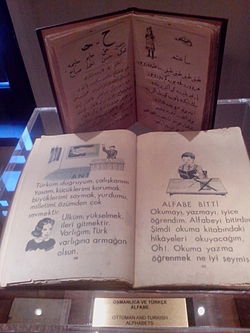

History

[edit]Early reform proposals and alternate scripts

[edit]The earliest known Turkic alphabet is the Orkhon script, also known as the Old Turkic alphabet, the first surviving evidence of which dates from the 7th century. In general, Turkic languages have been written in a number of different alphabets including Uyghur, Cyrillic, Arabic, Greek, Latin, and some other Asiatic writing systems.

Ottoman Turkish was written using a Turkish form of the Arabic script for over 1,000 years. It was poorly suited to write works that incorporated a great deal of Arabic and Persian vocabulary as their spellings were largely unphonetic and thus had to be memorized. This created a significant barrier of entry as only highly formal and prestige versions of Turkish were top heavy in Arabic and Persian vocabulary. Not only would students have trouble predicting the spellings of certain Arabic and Persian words, but some of these words were so rarely used in common speech that their spellings would not register in the collective conscious of students. However, it was much better suited to the Turkish part of the vocabulary. Although Ottoman Turkish was never formally standardized by a decree of law, words of Turkic origin largely had de facto systematic spelling rules associated with them which made it easier to read and write.[10] On the rare occasion a Turkic word had irregular spelling that had to be memorized, there was often a dialectal or historic phonetic rationale that would be validated by observing the speech of eastern dialects, Azeri, and Turkmen. Whereas Arabic is rich in consonants but poor in vowels, Turkish is the opposite; the script was thus inadequate at distinguishing certain Turkish vowels and the reader was forced to rely on context to differentiate certain words. The introduction of the telegraph in the 19th century exposed further weaknesses in the Arabic script, although this was buoyed to some degree by advances in the printing press and Ottoman Turkish keyboard typewriters.[11]

Some Turkish reformists promoted the adoption of the Latin script well before Atatürk's reforms. In 1862, during an earlier period of reform, the statesman Münuf Pasha advocated a reform of the alphabet. At the start of the 20th century similar proposals were made by several writers associated with the Young Turks movement, including Hüseyin Cahit, Abdullah Cevdet, and Celâl Nuri.[11] The issue was raised again in 1923 during the first Economic Congress of the newly founded Turkish Republic, sparking a public debate that was to continue for several years.

A move away from the Arabic script was strongly opposed by conservative and religious elements. It was argued that Romanisation of the script would detach Turkey from the wider Islamic world, substituting a "foreign" (i.e. European) concept of national identity for the traditional sacred community. Others opposed Romanisation on practical grounds; at that time there was no suitable adaptation of the Latin script that could be used for Turkish phonemes. Some suggested that a better alternative might be to modify the Arabic script to introduce extra characters to better represent Turkish vowels.[12] In 1926, however, the Turkic republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major boost to reformers in Turkey.[11]

Turkish-speaking Armenians used the Mesrobian script to write the Bible and other books in Turkish for centuries. Karamanli Turkish was, similarly, written with a form of the Greek alphabet.

Atatürk himself had a longstanding conviction that the Turkish alphabet should be Latinised. He told Ruşen Eşref that he had been preoccupied with this idea during his time in Syria (1905–1907), and would later use a French-influenced Latinised rendering of Turkish in his private correspondence, as well as confide in Halide Edip in 1922 about his vision for a new alphabet. An early Latinisation of the Turkish language was made by Gyula Németh in his Türkische Grammatik, published in 1917, which had significant variations from the current script, for example using the Greek gamma where today's ğ would be used. Hagop Martayan (later Dilâçar) brought this to Mustafa Kemal's attention in the initial years after the book's publication but Kemal did not like this transcription.[13] The encounter with Martayan and looking at Németh's transcription represented the first instance where Kemal would see a systematically Latinised version of Turkish.[14]

Introduction of the modern Turkish alphabet

[edit]

The current 29-letter Turkish alphabet was established as a personal initiative of the founder of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. It was a key step in the cultural part of Atatürk's Reforms,[7] introduced following his consolidation of power. Having established a one-party state ruled by his Republican People's Party, Atatürk was able to sweep aside the previous opposition to implementing radical reform of the alphabet. He announced his plans in July 1928[15] and established a Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) consisting of the following members:[16]

- Ragıp Hulusi Özden

- İbrahim Grantay

- Ahmet Cevat Emre

- Mehmet Emin Erişirgil

- İhsan Sungu

- Avni Başman

- Falih Rıfkı Atay

- Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın

- Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu

The commission was responsible for adapting the Latin script to meet the phonetic requirements of the Turkish language. The resulting Latin alphabet was designed to reflect the actual sounds of spoken Turkish, rather than simply transcribing the old Ottoman script into a new form.[17]

Atatürk himself was personally involved with the commission and proclaimed an "alphabet mobilisation" to publicise the changes. He toured the country explaining the new system of writing and encouraging the rapid adoption of the new alphabet.[17] The Language Commission proposed a five-year transition period; Atatürk saw this as far too long and reduced it to three months.[18] The change was formalised by the Turkish Republic's law number 1353, the Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet, passed on 1 November 1928.[19][20] Starting 1 December 1928, newspapers, magazines, subtitles in movies, advertisement and signs had to be written with the letters of the new alphabet. From 1 January 1929, the use of the new alphabet was compulsory in all public communications as well the internal communications of banks and political or social organisations. Books had to be printed with the new alphabet as of 1 January 1929 as well. The civil population was allowed to use the old alphabet in their transactions with the institutions until 1 June 1929.[21]

In the Sanjak of Alexandretta (today's province of Hatay), which was at that time under French control and would later join Turkey, the local Turkish-language newspapers adopted the Latin alphabet only in 1934.[22]

The reforms were also backed up by the Law on Copyrights, issued in 1934, encouraging and strengthening the private publishing sector.[23] In 1939, the First Turkish Publications Congress was organised in Ankara for discussing issues such as copyright, printing, progress on improving the literacy rate and scientific publications, with the attendance of 186 deputies.

Political and cultural aspects

[edit]As cited by the reformers, the old Arabic script was much more difficult to learn than the new Latin alphabet.[24] The literacy rate did indeed increase greatly after the alphabet reform, from around 10% to over 90%, [clarification needed] but many other factors also contributed to this increase, such as the foundation of the Turkish Language Association in 1932, campaigns by the Ministry of Education, the opening of Public Education Centres throughout the country, and Atatürk's personal participation in literacy campaigns.[25]

Atatürk also commented on one occasion that the symbolic meaning of the reform was for the Turkish nation to "show with its script and mentality that it is on the side of world civilisation".[26] The second president of Turkey, İsmet İnönü further elaborated the reason behind adopting a Latin alphabet:

The alphabet reform cannot be attributed to ease of reading and writing. That was the motive of Enver Pasha. For us, the big impact and the benefit of an alphabet reform was that it eased the way to cultural reform. We inevitably lost our connection with Arabic culture.[27]

The Turkish writer Şerif Mardin has noted that "Atatürk imposed the mandatory Latin alphabet in order to promote the national awareness of the Turks against a wider Muslim identity. It is also imperative to add that he hoped to relate Turkish nationalism to the modern civilisation of Western Europe, which embraced the Latin alphabet."[28] The explicitly nationalistic and ideological character of the alphabet reform showed in the booklets issued by the government to teach the population the new script. They included sample phrases aimed at discrediting the Ottoman government and instilling updated Turkish values, such as: "Atatürk allied himself with the nation and drove the sultans out of the homeland"; "Taxes are spent for the common properties of the nation. Tax is a debt we need to pay"; "It is the duty of every Turk to defend the homeland against the enemies." The alphabet reform was promoted as redeeming the Turkish people from the neglect of the Ottoman rulers: "Sultans did not think of the public, Ghazi commander [Atatürk] saved the nation from enemies and slavery. And now, he declared a campaign against ignorance [illiteracy]. He armed the nation with the new Turkish alphabet."[29]

The historian Bernard Lewis has described the introduction of the new alphabet as "not so much practical as pedagogical, as social and cultural – and Mustafa Kemal, in forcing his people to accept it, was slamming a door on the past as well as opening a door to the future". It was accompanied by a systematic effort to rid the Turkish language of Arabic and Persian loanwords, often replacing them with revived early Turkic words. However, the same reform also rid the language of many Western loanwords, especially French, in favor of Turkic words, albeit to a lesser degree. Atatürk told his friend Falih Rıfkı Atay, who was on the government's Language Commission, that by carrying out the reform, "we were going to cleanse the Turkish mind from its Arabic roots."[30]

Yaşar Nabi, a leading journalist, argued in the 1960s that the alphabet reform had been vital in creating a new Western-oriented identity for Turkey. He noted that younger Turks, who had only been taught the Latin script, were at ease in understanding Western culture but were quite unable to engage with Middle Eastern culture.[31] The new script was adopted very rapidly and soon gained widespread acceptance. Even so, older people continued to use the Turkish Arabic script in private correspondence, notes and diaries until well into the 1960s.[17]

Keyboard layout

[edit]The standard Turkish keyboard layouts for personal computers are shown below. The first is known as Turkish F, designed in 1955 by the leadership of İhsan Sıtkı Yener with an organization based on letter frequency in Turkish words. The second as Turkish Q, an adaptation of the QWERTY keyboard to include six additional letters found in the Turkish language.

Turkish F-keyboard

Turkish Q-keyboard

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Talat Tekin (1997). Tarih Boyunca Türkçenin Yazısı. Türk Dilleri Araştırmaları Dizisi (in Turkish). Ankara: Simurg. p. 72. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Dooley, Ian (6 October 2017). "New Nation, New Alphabet: Azerbaijani Children's Books in the 1990s". Cotsen Children's Library (in English and Azerbaijani). Princeton University WordPress Service. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Soyegov, M. New Turkmen Alphabet: several questions on its development and adoption Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Шаяхметова, Жанна (2021-02-01). "Kazakhstan Presents New Latin Alphabet, Plans Gradual Transition Through 2031". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2022-09-02.

- ^ "Türkçede "ka" sesi yoktur" (in Turkish). Turkish Language Association on Twitter. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ "Alphabet and Character Frequency: Turkish (Türkçe)".

- ^ a b Yazım Kılavuzu, Dil Derneği, 2002 (the writing guide of the Turkish language)

- ^ "Turkish Java Needs Special Brewing | Java IoT". 2017-07-26. Archived from the original on 2017-07-26. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ "Sorting and String Comparison". Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ Joomy Korkut. "Morphology and lexicon-based machine translation of Ottoman Turkish to Modern Turkish" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-20. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- ^ a b c Zürcher, Erik Jan. Turkey: a modern history, p. 188. I.B.Tauris, 2004. ISBN 978-1-85043-399-6

- ^ Gürçağlar, Şehnaz Tahir. The politics and poetics of translation in Turkey, 1923–1960, pp. 53–54. Rodopi, 2008. ISBN 978-90-420-2329-1

- ^ Lewis, Geoffrey (1999). The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-19-823856-8.

- ^ Öztürk, Yaşar (April 2002). "Mustafa Kemal'in keşfettiği bilim adamımız: Agop Dilâçar" (PDF). Bütün Dünya: 19–20.

- ^ Nationalist Notes, TIME Magazine, July Archived 2003-10-09 at the Wayback Machine 23, 1928

- ^ "Harf Devrimi". dildernegi.org.tr. Dil Derneği. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Zürcher, p. 189

- ^ Gürçağlar, p. 55

- ^ Aytürk, İlker (2008). "The First Episode of Language Reform in Republican Turkey: The Language Council from 1926 to 1931". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (3): 281. doi:10.1017/S1356186308008511. hdl:11693/49487. ISSN 1356-1863. JSTOR 27755954. S2CID 162474551. Archived from the original on 2021-06-25. Retrieved 2021-06-20.

- ^ "Tūrk Harflerinin Kabul ve Tatbiki Hakkında Kanun" (PDF) (in Turkish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-10. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ^ Yilmaz (2013). Becoming Turkish (1st ed.). Syracuse, New York. p. 145. ISBN 9780815633174.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gilquin, Michel (2000). D'Antioche au Hatay (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 70. ISBN 2-7384-9266-5.

- ^ Press and Publications in Turkey,[permanent dead link] Newspot, June 2006, published by the Office of the Prime Minister, Directorate General of Press and Information.

- ^ Toprak, Binnaz. Islam and political development in Turkey, p. 41. BRILL, 1981. ISBN 978-90-04-06471-3

- ^ Harf İnkılâbı Archived 2006-06-21 at the Wayback Machine Text of the speech by Prof. Dr. Zeynep Korkmaz on the website of Turkish Language Association, for the 70th anniversary of the Alphabet Reform, delivered at the Dolmabahçe Palace, on September 26, 1998

- ^ Karpat, Kemal H. "A Language in Search of a Nation: Turkish in the Nation-State", in Studies on Turkish politics and society: selected articles and essays, p. 457. BRILL, 2004. ISBN 978-90-04-13322-8

- ^ İsmet İnönü (August 2006). "2". Hatıralar (in Turkish). Bilgi Yayinevi. p. 223. ISBN 975-22-0177-6.

- ^ Cited by Güven, İsmail in "Education and Islam in Turkey". Education in Turkey, p. 177. Eds. Nohl, Arnd-Michael; Akkoyunlu-Wigley, Arzu; Wigley, Simon. Waxmann Verlag, 2008. ISBN 978-3-8309-2069-4

- ^ Güven, pp. 180–81

- ^ Toprak, p. 145, fn. 20

- ^ Toprak, p. 145, fn. 21

External links

[edit]- Yunus Emre Enstitusu – Online Learning

- The Turkish Alphabet

- Online Turkish

- The Turkish Alphabet Pronunciation & Examples

- Dilek Nur Polat Ünsür (22 Mac 2021). "How Newspapers Familiarized Readers with the Latin Script During the Turkish Alphabet Reform", ATypI 2020 presentation

Turkish alphabet

View on GrokipediaThe Turkish alphabet is a phonetically precise variant of the Latin script comprising 29 letters, officially mandated by Law No. 1353 on 3 November 1928 to replace the Perso-Arabic Ottoman script, which inadequately represented Turkish phonology including vowel harmony and distinct consonants like /ç/ and /ş/.[1][2] This reform, spearheaded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, aimed to boost literacy rates—previously hindered by the complexity of Arabic-derived writing—and align Turkey with Western modernization by severing orthographic ties to Islamic scriptural traditions, thereby enabling rapid education of the populace in the new Republic.[3][4] The alphabet incorporates seven modified letters (ç, ğ, ı, ö, ş, ü, and the dotted İ) absent from the standard Latin set, ensuring one-to-one sound-letter correspondence that reflects Turkish's agglutinative structure and phonetic consistency.[2] Subsequent to its adoption, the Turkish Language Association (TDK), established in 1932 under Atatürk's directive, has overseen standardization and purification efforts, promoting neologisms to displace Arabic and Persian loanwords while preserving the alphabet's core design despite contemporary discussions on a unified Turkic script.[5][6] The reform's success is evidenced by Turkey's literacy surge from under 10% in 1927 to near-universal levels by the late 20th century, though critics contend it contributed to cultural disconnection from Ottoman literary heritage and accelerated secularization at the expense of historical continuity.[3][4]

Orthography and Letters

Composition and ordering

The modern Turkish alphabet consists of 29 letters, as defined by the Turkish Language Association (TDK).[7] These letters follow a standardized ordering established under Law No. 1353, enacted on November 1, 1928, which formalized the adoption of a Latin-based script tailored to Turkish.[8] The sequence begins with A and proceeds alphabetically, incorporating modified forms to distinguish unique characters: A, B, C, Ç, D, E, F, G, Ğ, H, I, İ, J, K, L, M, N, O, Ö, P, R, S, Ş, T, U, Ü, V, Y, Z.[7] This ordering excludes Q, W, and X, which are absent from the Turkish inventory.[9] Each letter has distinct uppercase and lowercase variants, with diacritics applied to six letters for visual differentiation: Ç/ç (cedilla), Ğ/ğ (breve), I/ı (dotless i), İ/i (dotted i), Ö/ö (diaeresis), Ş/ş (cedilla), and Ü/ü (diaeresis).[7] The full set is presented below:| Uppercase | Lowercase |

|---|---|

| A | a |

| B | b |

| C | c |

| Ç | ç |

| D | d |

| E | e |

| F | f |

| G | g |

| Ğ | ğ |

| H | h |

| I | ı |

| İ | i |

| J | j |

| K | k |

| L | l |

| M | m |

| N | n |

| O | o |

| Ö | ö |

| P | p |

| R | r |

| S | s |

| Ş | ş |

| T | t |

| U | u |

| Ü | ü |

| V | v |

| Y | y |

| Z | z |

Phonetic principles and distinctive letters

The Turkish alphabet is structured as a phonemic orthography, exhibiting a strong correspondence between graphemes and phonemes that enables precise pronunciation from spelling alone.[10] This regularity stems from its adaptation to Turkish phonology, minimizing ambiguities and supporting high literacy rates post-adoption.[11] Central to this system are the eight vowel letters—a (/a/), e (/e/), ı (/ɯ/), i (/i/), o (/o/), ö (/ø/), u (/u/), ü (/y/)—which directly encode the language's vowel inventory while accommodating vowel harmony, whereby subsequent vowels in words and affixes match the preceding ones in backness (front vs. back) and rounding.[12] The undotted ı distinctly represents the close back unrounded vowel /ɯ/, a sound integral to Turkic roots and contrasted with the dotted i for the close front unrounded /i/, preventing homophony in minimal pairs like kısım (/kɯsɯm/, "part") versus kisim (hypothetical /kisːim/).[13] The front rounded vowels ö and ü fill orthographic gaps in the Latin base, denoting /ø/ (as in göz, "eye") and /y/ (as in gül, "rose"), which participate in harmony rules requiring rounded vowels to follow rounded antecedents in compatible positions.[14] These diacritics ensure the script reflects phonological contrasts without digraphs or ambiguities common in less tailored systems.[15] Consonantal innovations include ç for the postalveolar affricate /t͡ʃ/ (as in çocuk, "child") and ş for the postalveolar fricative /ʃ/ (as in şarkı, "song"), both essential for native sounds absent or variably represented in standard Latin.[16] The ğ (soft g or yumuşak ge) uniquely functions non-phonemically: it often elides as a consonant but lengthens or palatalizes the prior vowel (e.g., dağ /daː/, "mountain"; ağa /aɟa/, "lord"), accommodating Turkish avoidance of vowel hiatus and certain clusters while preserving etymological traces.[17] This adaptation prioritizes phonological naturalness over strict biuniqueness, yet maintains overall predictability.[18]Adaptations for Turkish phonology

The Turkish Latin alphabet addresses key phonological features of the language by providing dedicated graphemes for its eight vowels—a (/a/), e (/e/), ı (/ɯ/), i (/i/), o (/o/), ö (/ø/), u (/u/), and ü (/y/)—enabling precise orthographic representation without reliance on optional diacritics or contextual inference.[19] In contrast, the Ottoman Perso-Arabic script inadequately distinguished these vowels, as multiple sounds such as /o/, /u/, /ø/, and /y/ were ambiguously rendered by the single letter waw (و), particularly when diacritics (harakat) were omitted in everyday cursive writing, leading to frequent reading ambiguities.[1] This explicit vowel marking supports Turkish vowel harmony, a rule governing suffix selection based on front-back and rounded-unrounded distinctions, by ensuring morpheme boundaries remain phonetically transparent in agglutinative derivations.[20] Consonant representation prioritizes phonetic fidelity through single-letter forms for sounds absent or variably transcribed in Perso-Arabic, including ç for /t͡ʃ/, ş for /ʃ/, and ğ for the lenited velar /ɰ/ or approximant, avoiding digraphs that could complicate parsing in suffixed words.[19] Palatalization of velars (/k/ to , /g/ to [ɟ/]) and other assimilations before front vowels are handled via consistent spelling rather than orthographic shifts, relying on the reader's phonological knowledge while maintaining uniform grapheme-to-phoneme mapping.[19] This monographic approach, eschewing combinations like English "ch" or "sh," streamlines agglutination by preserving morpheme integrity in extended forms, such as verb conjugations or noun cases, where cumulative suffixes demand unambiguous segmentation.[20] Overall, these adaptations yield a near-phonemic script, with deviations limited to predictable rules like ğ's non-pronunciation in some positions, enhancing readability for a language where average word lengths exceed those in isolating tongues due to derivational morphology.[19]Historical Development

Limitations of the Ottoman Perso-Arabic script

The Ottoman Perso-Arabic script, adapted for Turkish with extensions for sounds absent in Arabic and Persian, featured 28 consonant letters but relied on optional diacritical marks—fatha for /a/, kasra for /i/, and damma for /u/—to indicate short vowels, which were routinely omitted in mature texts, rendering vowel representation inconsistent and ambiguous.[1] This deficiency was acute for Turkish phonology, which includes eight vowel phonemes organized by vowel harmony (distinguishing front vowels /e, i, ö, ü/ from back /a, ı, o, u/), a system the script could not systematically denote, as a single letter like و (waw) often ambiguously represented multiple vowels such as /o/, /u/, /ö/, or /ü/.[1][21] The script's cursive structure, in which letters altered form based on positional context and ligatured within words, further hindered legibility by blurring precise word boundaries; spaces separated graphemic units rather than semantic words, especially since certain letters (e.g., ا, د, ر) resisted connection to the following letter, allowing continuous flows that defied intuitive parsing without prior familiarity.[1] Moreover, distinctions between Turkish-specific realizations, such as the velar fricative /ɣ/ (a soft g) versus /g/, lacked dedicated markers, permitting diverse readings of the same orthographic sequence depending on regional or contextual interpretation.[22] These phonological mismatches contributed to literacy constraints, with rates among Ottoman Muslims estimated at 5-10% by the early 1920s, confined primarily to madrasa-educated religious scholars, scribes, and urban administrative elites who acquired skills through rote memorization rather than phonetic transparency.[23][1] Overall empire-wide literacy hovered around 10-15% in the early twentieth century, reflecting the script's opacity for the broader Turkic-speaking populace unversed in Arabic-Persian grammatical conventions.[24]Early 19th- and early 20th-century reform attempts

In the mid-19th century, Ottoman intellectuals began critiquing the Perso-Arabic script's limitations for Turkish, which lacked consistent vowel notation and phonetic precision, prompting early reform proposals amid Tanzimat modernization efforts. In May 1862, Münif Pasha addressed the Ottoman Scientific Society, emphasizing the script's deficiencies in facilitating education and literacy, and called for orthographic adjustments to align writing more closely with spoken Turkish.[25] These initiatives focused on pragmatic simplifications, such as enhanced diacritics or separated letter forms, rather than wholesale script replacement, reflecting concerns over printing inefficiencies and low literacy rates estimated below 10% in the empire.[26] The Young Turk Revolution of 1908 intensified these discussions within Committee of Union and Progress circles, where debates pitted advocates of Latin script adoption—citing its phonetic advantages and European compatibility—against defenders of a reformed Arabic system to preserve cultural ties.[27] Pan-Turkic ideas from Russian Empire reformers, including Mirza Fatali Akhundov's 1860s Latin proposals for Azerbaijani Turkish, influenced Ottoman thinkers by highlighting script mismatches in agglutinative Turkic languages, though no unified policy emerged amid political instability.[26] A notable wartime experiment occurred under War Minister Enver Pasha, who in 1914 devised the Hurûf-ı munfasıla (disjoined letters) system, modifying Arabic script with detached forms, vowel indicators, and reduced ligatures to ease soldier literacy and telegraphy.[28] Implemented in military training manuals and select publications, it aimed to boost efficiency without abandoning Islamic heritage but saw limited civilian uptake due to World War I disruptions and the Ottoman collapse by 1918, preventing broader testing or enforcement.[29] Influences from Tatar Jadid reformers' phonetic Arabic adaptations in the Russian Empire further informed these efforts, underscoring shared Turkic challenges, yet empire-wide adoption eluded all proposals amid prioritizing survival over linguistic engineering.[26]The 1928 adoption under Atatürk

In July 1928, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk announced plans to replace the Ottoman Arabic script with a Latin-based alphabet adapted for Turkish phonology, and formed the Language Commission (Dil Encümeni) to develop it.[30] The commission, comprising linguists, educators, and officials such as Ragıp Hulusi Özden and İbrahim Necmi Dilmen, created an alphabet of 29 letters derived from the Latin script but modified with additions like the undotted ı, dotted i, ç, ğ, ö, ş, and ü to better represent Turkish vowel harmony and consonant sounds, ensuring one-to-one grapheme-phoneme correspondence.[31] On August 9, 1928, Atatürk personally introduced the new letters to the public during a Republican People's Party event in Istanbul's Sarayburnu Park, demonstrating their use on a blackboard.[32] The Grand National Assembly of Turkey enacted the reform through Law No. 1353, titled "Adoption and Application of the Turkish Alphabet," on November 1, 1928, which officially mandated the switch and required its use in public documents, education, and publications starting December 1, 1928.[33][34] The law was published in the Official Gazette on November 3, 1928, marking the formal end of the Arabic script's mandatory use.[35] Atatürk actively promoted the alphabet through personal involvement, including public demonstrations and teaching sessions, to accelerate its acceptance. Initial dissemination began in late 1928 via the Millet Mektepleri (Nation's Schools), a network of adult literacy classes aimed at rapid instruction in the new script across the population.[35]Implementation and Enforcement

Timeline of rollout and public education campaigns

The new Turkish alphabet was publicly announced by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk on August 9, 1928, at Sarayburnu Park in Istanbul, marking the initial step in disseminating the script to the populace.[32] Following the formal adoption via the Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet on November 1, 1928, Atatürk personally conducted public demonstrations of the letters, including a session in Kayseri on September 20, 1928, where he used blackboards to teach basic reading and writing to crowds.[1] From December 1, 1928, newspapers, magazines, and film subtitles began printing exclusively in the Latin-based script, accelerating elite and urban exposure.[34] Mass education initiatives commenced with the opening of Millet Mektepleri (Nation's Schools) on January 1, 1929, targeting adults across urban and initial rural sites with simplified primers and evening classes focused on phonetic principles of the new letters.[36] These campaigns involved transliteration of key texts, such as Atatürk's Nutuk, into the new script by late 1928 to provide accessible reading material for learners.[1] Public signage and official documents shifted within months, with widespread conversion in print media by early 1929, fostering practical familiarity among the educated classes before broader dissemination.[27] By 1930, Millet Mektepleri had expanded to provincial and rural areas, integrating the script into compulsory primary education frameworks established under the 1924 Tevhid-i Tedrisat Law, with itinerant teachers conducting outdoor sessions modeled on Atatürk's demonstrations.[37] The campaigns continued through the early 1930s, achieving operational dominance of the new alphabet in public communications by mid-decade, as evidenced by the phasing out of parallel Ottoman script usage in educational primers.[36]Legal measures and suppression of the old script

On November 1, 1928, the Grand National Assembly enacted Law No. 1353, titled the "Law on the Adoption and Implementation of the Turkish Alphabet," which mandated the exclusive use of the new Latin-based alphabet in all official state business, public communications, and education, thereby prohibiting the Ottoman Arabic script in these domains with the exception of religious texts in mosques.[34][38] The law took effect immediately upon publication in the Official Gazette on November 3, 1928, establishing the state's authority to enforce uniformity through centralized oversight of governmental and institutional documentation.[34] Enforcement mechanisms included penal sanctions under Turkish criminal provisions linked to the 1928 law, imposing imprisonment ranging from two to six months for non-compliance in official contexts, such as failing to use the prescribed alphabet in state-required writings.[39] Additional penalties, including fines, were applied to violators, reinforcing the prohibition through direct legal deterrents rather than voluntary adoption.[40] By January 1, 1929, the restrictions extended beyond official use to private publishing, banning the production and distribution of Turkish-language books, newspapers, magazines, advertisements, and notices in the Arabic script, which effectively curtailed its dissemination in non-state spheres.[40] The government asserted a monopoly over printing presses and educational materials compatible with the new script, phasing out Arabic-script type and resources to preclude parallel systems and compel transition without provisions for gradual coexistence.[1] This top-down control over production and distribution overrode potential incremental approaches, ensuring the old script's rapid obsolescence in practical application.[40]Resistance during the transition period

Conservative and religiously traditional segments of Turkish society, particularly those attached to Islamic scholarly practices, expressed opposition to the 1928 alphabet reform, viewing it as a disruption to established cultural and linguistic norms tied to Ottoman heritage.[4] Prominent intellectuals like Mehmet Fuat Köprülü initially argued against adopting the Latin script, contending it would not accelerate Western integration as intended.[4] Clerical circles, aligned with traditional Islamic values, contributed to this pushback through informal resistance, though organized clerical campaigns remained limited.[4] A notable instance of formal dissent came via a petition submitted on 17 April 1931 by former assembly president Halil to Mustafa Kemal, urging reconsideration of the reform's societal disruptions.[27] Underground persistence of the Ottoman script occurred in private and manuscript contexts, where authors continued drafting in Arabic letters, relying on intermediaries to transcribe into Latin for official submission; this practice endured for years despite prohibitions.[27] The Republican regime enforced compliance through legal measures, declaring Ottoman script use unlawful effective 1 January 1929 and issuing monitoring circulars, such as one from Şükrü Kaya on 12 January 1930, to penalize violations; while specific arrest tallies are sparse, suppression targeted holdouts in the 1920s and 1930s.[27][4] Rural areas exhibited prolonged holdouts due to geographic isolation and scarce enforcement resources, resulting in delayed adoption compared to urban centers.[27] Older generations experienced acute alienation, rendered functionally illiterate in the new system as their Ottoman literacy became obsolete, severing access to ancestral texts and fostering a generational linguistic divide; personal accounts from the era document struggles with relearning basic reading.[27][41] Overall, documented resistance lacked large-scale organized revolt, manifesting instead as passive noncompliance and localized persistence.[41]Political Motivations and Ideology

Link to secular Kemalist reforms

The adoption of the Latin-based Turkish alphabet in 1928 formed an integral part of the secularism (laiklik) principle among Kemalism's Six Arrows, which sought to rigorously separate religion from state affairs and public life. By discarding the Perso-Arabic script, historically intertwined with the Quran and Islamic jurisprudence, the reform aimed to erode the sacral character of written Turkish and facilitate the state's laicization efforts. This shift aligned with broader Kemalist initiatives, such as the 1924 abolition of the caliphate and the closure of madrasas, to diminish the Ottoman-Islamic legacy's hold on cultural and educational institutions. Atatürk explicitly framed the script change as a means to liberate Turkish literacy from its dependence on religious scholarship, where proficiency in the Arabic script necessitated mastery of Arabic grammar and vocabulary—domains monopolized by the ulema. Pre-reform literacy, estimated at around 10% in 1927, was predominantly religious in nature, confined to theological education that reinforced clerical authority over interpretation of sacred texts. The new alphabet's phonetic design enabled rapid dissemination of secular knowledge through state-controlled schools, thereby transferring narrative control from religious elites to the republican bureaucracy. Historians note that this reform's anti-clerical thrust was evident in Atatürk's public campaigns, where he personally instructed citizens on the Latin letters to underscore the break from "Eastern" scriptural traditions. By severing access to Ottoman archives without specialized training, the policy pragmatically curtailed the ulema's interpretive power, fostering a realist state monopoly on historical and ideological discourse unmediated by Islamic orthodoxy.[42]Promotion of Westernization and nationalism

The adoption of the Latin-based Turkish alphabet in 1928 formed a pivotal element of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's broader Westernization agenda, positioning the nascent Republic of Turkey within the orbit of European modernity and secularism while repudiating the Ottoman Empire's entrenched Perso-Arabic scriptural traditions.[5] This reform symbolized a conscious pivot toward Western cultural paradigms, enabling Turkey to emulate the technological and educational advancements of Europe by facilitating direct engagement with Latin-script materials.[43] The new script was derived from the Latin alphabet employed in Western languages, incorporating modifications such as diacritics for unique Turkish sounds (e.g., <ç>, <ğ>, <ı>, <ö>, <ş>, <ü>) while deliberately excluding letters like,Causally, the Latin script's prevalence in global scientific publishing and technical documentation expedited the transfer of Western knowledge to Turkey, underpinning advancements in industry, science, and public administration by obviating the need for complex transliterations from the prior cursive Perso-Arabic system.[45] Nonetheless, the decision privileged alignment with contemporary European conventions over resurrecting indigenous alternatives, such as the Orkhon runic inscriptions employed by early Turkic khaganates from the 8th century CE, which might have accentuated pre-Islamic ethnic continuity but lacked the practicality for mass literacy and international interoperability in the 20th century.[45] This orientation reflects a strategic emphasis on functional Western integration, sometimes at the expense of symbolic fidelity to ancient Turkic precedents in mainstream historical interpretations., and that lacked equivalents in native Turkish phonology, thus crafting a streamlined system tailored exclusively to the language's requirements.[44] This exclusion underscored a nationalist impulse to purge extraneous elements inherited from the Ottoman era's multilingual and foreign-inflected lexicon, promoting a purified expression of "Turkishness" distinct from the cosmopolitanism of Arabic and Persian influences.[4]