Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

USBKill

View on Wikipedia| USBKill | |

|---|---|

| |

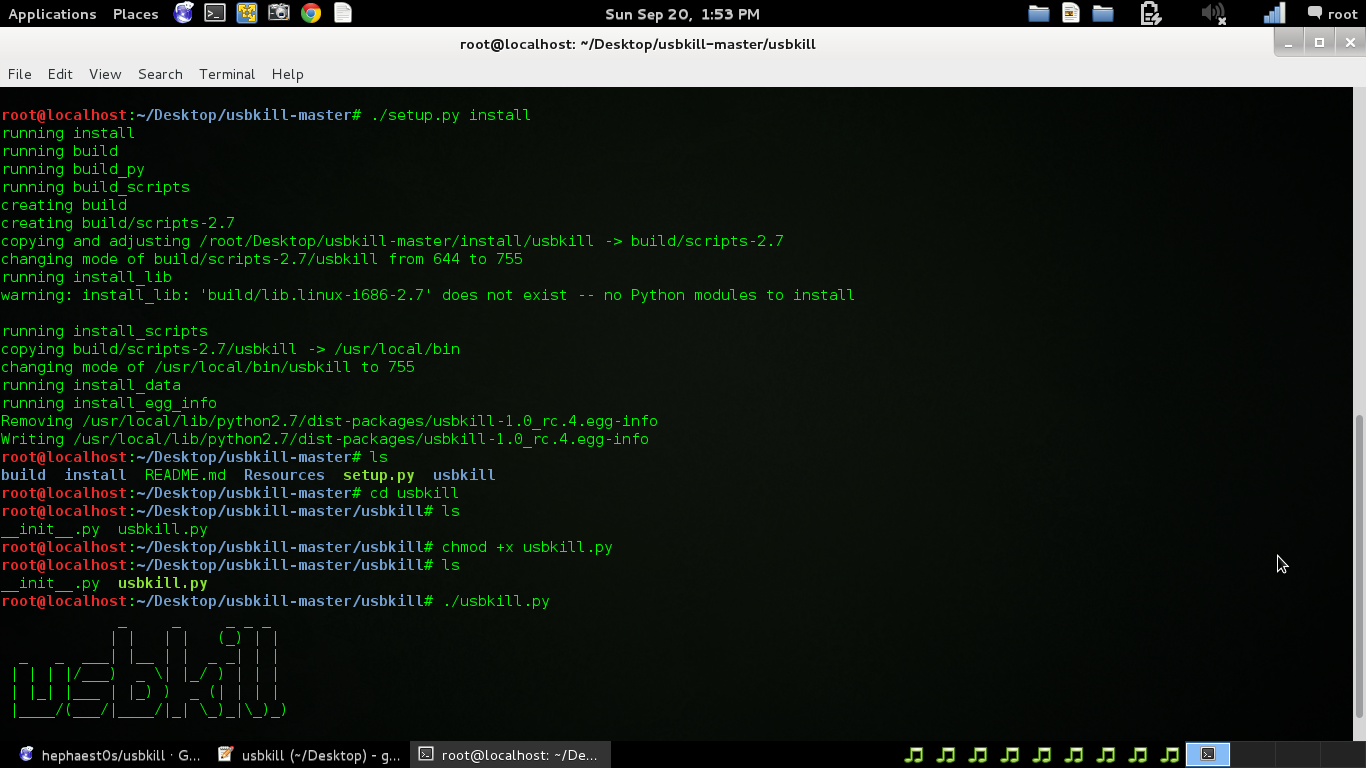

A USBKill installation in Linux | |

| Developer | Hephaest0s |

| Stable release | 1.0-rc4

/ January 18, 2016 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | Python |

| Operating system | BSD, Linux, macOS, other Unix-like systems |

| Size | 15.6 KB |

| Type | Anti-forensic |

| License | GNU General Public License |

| Website | github |

USBKill is anti-forensic software distributed via GitHub, written in Python for the BSD, Linux, and OS X operating systems. It is designed to serve as a kill switch if the computer on which it is installed should fall under the control of individuals or entities against the desires of the owner.[1] It is free software, available under the GNU General Public License.[2]

The program's developer, who goes by the online name Hephaest0s, created it in response to the circumstances of the arrest of Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht, during which U.S. federal agents were able to get access to incriminating evidence on his laptop without needing his cooperation by copying data from its flash drive after distracting him.[3] It maintains a whitelist of devices allowed to connect to the computer's USB ports; if a device not on that whitelist connects, it can take actions ranging from merely returning to the lock screen to encrypting the hard drive, or wiping all data on the computer. However, it can also be used as part of a computer security regimen to prevent the surreptitious installation of malware or spyware or the clandestine duplication of files, according to its creator.[4]

Background

[edit]When law enforcement agencies began making computer crime arrests in the 1990s, they would often ask judges for no knock search warrants, to deny their targets time to delete incriminating evidence from computers or storage media. In more extreme circumstances where it was likely that the targets could get advance notice of arriving police, judges would grant "power-off" warrants, allowing utilities to turn off the electricity to the location of the raid shortly beforehand, further forestalling any efforts to destroy evidence before it could be seized. These methods were effective against criminals who produced and distributed pirated software and movies, which was the primary large-scale computer crime of the era.[1]

By the 2010s, the circumstances of computer crime had changed along with legitimate computer use. Criminals were more likely to use the Internet to facilitate their crimes, so they needed to remain online most of the time. To do so, and still keep their activities discreet, they used computer security features like lock screens and password protection.[1]

For those reasons, law enforcement now attempts to apprehend suspected cybercriminals with their computers on and in use, all accounts both on the computer and online open and logged in, and thus easily searchable.[1] If they fail to seize the computer in that condition, there are some methods available to bypass password protection, but these may take more time than police have available. It might be legally impossible to compel the suspect to relinquish their password; in the United States, where many computer-crime investigations take place, courts have distinguished between forcing a suspect to use material means of protecting data such as a thumbprint, retinal scan, or key, as opposed to a password or passcode, which is purely the product of the suspect's mental processes and is thus protected from compelled disclosure by the Fifth Amendment.[5]

The usual technique for authorities—either public entities such as law enforcement or private organizations like companies—seizing a computer (usually a laptop) that they believe is being used improperly is first to physically separate the suspect user from the computer enough that they cannot touch it, to prevent them from closing its lid, unplugging it, or typing a command. Once they have done so, they often install a device in the USB port that spoofs minor actions of a mouse, touchpad, or keyboard, preventing the computer from going into sleep mode, from which it would usually return to a lock screen which would require a password.[6]

Agents with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigating Ross Ulbricht, founder of the online black market Silk Road, learned that he often ran the site from his laptop, using the wireless networks available at branches of the San Francisco Public Library. When they had enough evidence to arrest him, they planned to catch him in the act of running Silk Road, with his computer on and logged in. They needed to ensure he was unable to trigger encryption or delete evidence when they did.[3]

In October 2013, a male and female agent pretended to have a lovers' quarrel near where Ulbricht was working at the Glen Park branch. According to Business Insider, Ulbricht was distracted and got up to see what the problem was, whereupon the female agent grabbed his laptop while the male agent restrained Ulbricht. The female agent was then able to insert a flash drive into one of the laptop's USB ports, with software that copied key files.[3] According to Joshuah Bearman of Wired, a third agent grabbed the laptop while Ulbricht was distracted by the apparent lovers' fight and handed it to agent Tom Kiernan.[7]

Use

[edit]In response to the circumstances of Ulbricht's arrest,[4] a programmer known as Hephaest0s developed the USBKill code in Python and uploaded it to GitHub in 2014. It is available as free software under the GNU General Public License and currently runs under both Linux and OS X.[4]

The program, when installed, prompts the user to create a whitelist of devices that are allowed to connect to the computer via its USB ports, which it checks at an adjustable sample rate. The user may also choose what actions the computer will take if it detects a USB device not on the whitelist (by default, it shuts down and erases data from the RAM and swap file). Users need to be logged in as root. Hephaest0s cautions users that they must be using at least partial disk encryption along with USBKill to fully prevent attackers from gaining access;[4] Gizmodo suggests using a virtual machine that will not be present when the computer reboots.[8]

It can also be used in reverse, with a whitelisted flash drive in the USB port attached to the user's wrist via a lanyard serving as a key. In this instance, if the flash drive is forcibly removed, the program will initiate the desired routines. "[It] is designed to do one thing," wrote Aaron Grothe in a short article on USBKill in 2600, "and it does it pretty well." As a further precaution, he suggests users rename it to something innocuous once they have loaded it on their computers, in case someone might be looking for it on a seized computer to disable it.[6]

In addition to its designed purpose, Hephaest0s suggests other uses unconnected to a user's desire to frustrate police and prosecutors. As part of a general security regimen, it could be used to prevent the surreptitious installation of malware or spyware on, or copying of files from, a protected computer. It is also recommended for general use as part of a robust security practice, even when there are no threats to be feared.[4]

Variations and modifications

[edit]With his 2600 article, Grothe shared a patch that included a feature that allowed the program to shut down a network when a non-whitelisted USB is inserted into any terminal.[6] Nate Brune, another programmer, created Silk Guardian, a version of USBKill that takes the form of a loadable kernel module, thus "[remaking] this project as a Linux kernel driver for fun and to learn."[9] In the issue of 2600 following Grothe's article, another writer, going by the name Jack D. Ripper, explained how Ninja OS, an operating system designed for live flash drives, handles the issue: it uses a watchdog timer, in the form of a memory-resident bash script, that cycles a loop through the boot device (i.e., the flash drive) three times per second to see if it is still mounted, and reboots the computer if it is not.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Ducklin, Paul (May 8, 2015). "The USBKILL anti-forensics tool – it doesn't do *quite* what it says on the tin". Naked Security. Sophos. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Hephaest0s (January 18, 2016). "usbkill.py". GitHub. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Bertrand, Natasha (May 29, 2015). "The FBI staged a lovers' fight to catch the kingpin of the web's biggest illegal drug marketplace". Business Insider. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Hephaest0s (2016). "Hephaest0s/usbkill". GitHub. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Vaas, Lisa (November 3, 2014). "Police can demand fingerprints but not passcodes to unlock phones, rules judge". Naked Security. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c Grothe, Aaron (Winter 2015–16). "USBKill: A Program for the Very Paranoid Computer User". 2600: The Hacker Quarterly. 32 (4): 10–11.

- ^ Bearman, Joshuah (May 2015). "The Rise and Fall of Silk Road Part II". Wired. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ^ Mills, Chris (May 5, 2015). "Simple Code Turns Any USB Drive Into A Kill Switch For Your Computer". Gizmodo. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ Brune, Nate. "Silk Guardian". GitHub. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ Ripper, Jack D. (Spring 2016). "Another Solution to the USBKill.py Problem". 2600. 33 (1): 48–49.