Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Unstart

View on Wikipedia

In supersonic aerodynamics, an unstart refers to a generally violent breakdown of the supersonic airflow. The phenomenon occurs when mass flow rate changes significantly within a duct. Avoiding unstarts is a key objective in the design of the engine air intakes of supersonic aircraft that cruise at speeds in excess of Mach 2.2.

Etymology

[edit]The term originated during the use of early supersonic wind tunnels. “Starting” the supersonic wind tunnel is the process in which the air becomes supersonic; unstart of the wind tunnel is the reverse process.[1] The shock waves that develop during the starting or unstart process may be visualized with schlieren or shadowgraph optical techniques.

In some contexts, the terms aerodynamic disturbance (AD) and unstart have been synonymous.

In aircraft engine intakes

[edit]The design of some air intakes for supersonic aircraft can be compared to that of supersonic wind tunnels, and requires careful analysis in order to avoid unstarts.[2] At high supersonic speeds (usually between Mach 2 to 3), intakes with internal compression are designed to have supersonic flow downstream of the air intake's capture plane. If the mass flow across the intake's capture plane does not match the downstream mass flow at the engine, the intake will unstart. This can cause violent, temporary loss of control until the intake is restarted.[3]

Few aircraft, although many ramjet-powered missiles, have flown with intakes which have supersonic compression taking place inside the intake duct. These intakes, known as mixed-compression intakes, have advantages for aircraft that cruise at Mach 2.2 and higher.[4] Most supersonic aircraft intakes compress the air externally, so do not start and hence have no unstart mode. Mixed compression intakes have the initial supersonic compression externally and the remainder inside the duct. As an example, the intakes on the North American XB-70 Valkyrie had an external compression ratio (cr) at Mach 3 of 3.5 and internal cr about 6.6,[5] followed by subsonic diffusion. The Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird and XB-70 Valkyrie had well-publicised[6][7] unstart behaviour. Other aircraft that have flown with internal compression include the Vought F-8 Crusader III, the SSM-N-9 Regulus II cruise missile[8] and the B-1 Lancer.[9]

Partial internal compression was considered for the Concorde (the Supersonic Transport Aircraft Committee, in 1959, had recommended an SST to cruise at Mach 2.2[10]) but an "external configuration was chosen for the inherent stability of its shock system, it had no unstart mode".[11] Even though there was some internal compression terminated by a normal shock local to the ramp boundary layer bleed slot inside the intake,[12] the intake was aerodynamically self-compensating with no trace of any unstart problem.[13] Early in the development of the B-1 Lancer its mixed external/internal intake was changed to an external one, technically safer but with a small compromise in cruise speed.[14] It subsequently had fixed intakes to reduce complexity, weight and cost.[15]

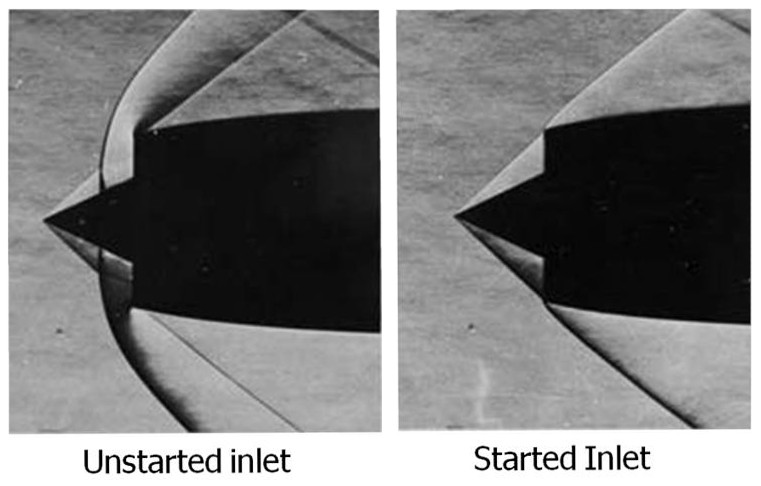

Work in the 1940s, for example by Oswatitsch,[16] showed that supersonic compression within a duct, known as a supersonic diffuser, becomes necessary at Mach 2 to 3 to increase the pressure recovery over that obtainable with external compression. As flight speed increases supersonically the shock system is initially external. For the SR-71 this was until about Mach 1.6 to Mach 1.8[17] and Mach 2 for the XB-70.[18] The intake is said to be unstarted. Further increase in speed produces supersonic speeds inside the duct with a plane shock near the throat. The intake is said to be started. Upstream or downstream disturbances, such as gusts/atmospheric temperature gradients and engine airflow changes, both intentional and unintentional (from surging), tend to cause the shock to be expelled almost instantaneously. Expulsion of the shock, known as an unstart, causes all the supersonic compression to take place externally through a single plane shock. The intake has changed in a split second from its most efficient configuration with most of its supersonic compression taking place inside the duct to the least efficient as shown by the large loss in pressure recovery, from about 80% to about 20% at Mach 3 flight speeds.[19] There is a large drop in intake pressure and loss in thrust together with temporary loss of control of the aircraft.

Not to be confused with an unstart, with its large loss in duct pressure, is the duct over-pressure resulting from a hammershock.[20] At speeds below the intake starting speed, or on aircraft with external compression intakes, engine surge or compressor stall can cause a hammershock. Above the intake starting speed, unstarts can cause stalls depending on the intake systems design complexity. Note that a hammershock can also occur with an external compression intake that has no unstart modes.[21] Hammershocks have caused damage to intakes. For example, the North American F-107 during flight at high speed experienced an engine surge which bent the intake ramps. The Concorde, during development flight testing, experienced significant damage to one nacelle after both engines surged.[22]

Intentional

[edit]When an unstart occurred on the SR-71, a very large amount of drag from the unstarted nacelle caused extreme rolling/yawing. The aircraft had an automatic restart procedure which balanced the drag by unstarting the other intake. This intake had its own tremendous amount of drag, with the spike fully forward to capture the shock wave in front of the intake.[23]

Avoidance

[edit]Decelerating from Mach 3 required a reduction of thrust which could unstart an intake with the reduced engine airflow. The SR-71 descent procedure used bypass flows to give unstart margin as the engine flow was reduced.

Thrust reduction on the XB-70 was achieved by keeping the engine flow stable at 100% rpm even with idle selected with the throttle. This was known as "rpm lock-up" and thrust was reduced by increasing the nozzle area. The compressor speed was maintained until the aircraft had slowed to Mach 1.5.[7]

Theoretical basis

[edit]Using a more theoretical definition, unstart is the supersonic choking phenomenon that occurs in ducts with an upstream mass flow greater than the downstream mass flow. Unsteady flow results as the mismatch in massflow cannot gradually propagate upstream in contrast to subsonic flow. Instead, in supersonic flow, the mismatch is carried forward behind a 'normal' or terminal shock wave that abruptly causes the gas flow to become subsonic. The resulting normal shock wave then propagates upstream at an effective acoustic velocity until the flow mismatch reaches equilibrium.

There are other ways of conceptualizing unstart which can be helpful. Unstart can be alternatively thought of in terms of a decreasing stagnation pressure inside of a supersonic duct; whereby the upstream stagnation pressure is greater than the downstream stagnation pressure. Unstart is also the result of a decreasing throat size in supersonic ducts. That is the entrance throat is larger than the diffusing throat. This change in throat size gives rise to the decreasing mass flow which defines unstart.[24]

The choking reaction of unstart results in the formation of a shock wave inside of the duct.

Shock instability or buzz

[edit]Under certain conditions, the shock wave in front or within a duct may be unstable, and oscillate upstream and downstream especially when interacting with the boundary layer. This phenomenon is known as buzz.[25] Stronger shock waves interacting with low momentum fluid or boundary layer tend to be unsteady and cause buzz. Buzz conditions can cause structural dynamics-induced failure if adequate margins are not incorporated into design.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ Liepmann, H.W. & Roshko, A. (1957). "Flow in Ducts and Wind Tunnels". Elements of Gasdynamics. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-53460-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ "Active Inlet Control". www.grc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2000-01-08.

- ^ Barnes, TD. "The Blackbird Unstart by CIA A-12 Project Frank Murray". roadrunnersinternationale.com.

- ^ Gary L. Cole; George H. Neiner; Miles O. Dustin (August 1978). "Wind tunnel evaluation of YF-12 inlet response to internal airflow disturbances with and without control" (PDF). Nasa. Dryden Flight Res. Center Yf-12 Experiments Symp., Vol. 1. Lewis Research Center: 157. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ B-70 Aircraft Study Final Report Volume IV SD 72-SH-0003 April 1972, L.J.Taube, Space Division, North American Rockwell, p. IV-8

- ^ "SR-71 Revealed The Inside Story, Richard H. Graham 1996, Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0-7603-0122-7, pp. 56-60

- ^ a b "Valkyrie" Jenkins & Landis 2004, Specialty Press, ISBN 1-58007-072-8, pp.136-137,144

- ^ "Jet Propulsion For Aerospace Applications" Second Edition, Hesse & Mumford 1964, Pitman Publishing Corporation, Library of Congress Catalog Number: 64-18757, pp.124-125

- ^ "Design for Air Combat" Ray Whitford 1987, Jane's Publishing company Limited, ISBN 0 7106 0426 2, p.132

- ^ "Evolution Of The Airliner" Ray Whitford 2007, The Crowood Press, ISBN 978 1 86126 870 9, p.172

- ^ "Design and Development of an Air Intake for a Supersonic Transport Aircraft" Rettie & Lewis, Journal of Aircraft, Volume 5 November–December 1968 Number 6, p.514

- ^ "Intake Aerodynamics" Second Edition 1999, Seddon and Goldsmith, AIAA Education Series, ISBN 0-632-04963-4, p.299

- ^ "concorde | 1969 | 0419 | Flight Archive". Flightglobal.com. 1967. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ^ "1974 | 2118 | Flight Archive". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ^ "Design for Air Combat" Ray Whitford 1987, Jane's Publishing company Limited, ISBN 0 7106 0426 2, p.119

- ^ Kl. Oswatitsch (June 1947). "Pressure recovery for missiles with reaction propulsion at high supersonic speeds" (PDF). Forschungen und Entwicklungen des Heereswaffenamtes (1005). NASA. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- ^ "Flying the SR-71 Blackbird" Col. Richard H. Graham, USAF(Retd.) 2008, Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0-7603-3239-9, p.170

- ^ "Conference on Aircraft Aerodynamics" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. May 1966. pp. 191, Fig.2. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ J. Thomas Anderson (19 August 2013). "How Supersonic Inlets Work" (PDF). Lockheed Martin Corporation. Aircraft Engine Historical Society. p. Fig.22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Hamstra, Jeffrey W.; McCallum, Brent N. (26 June 2017). "Tactical Aircraft Aerodynamic Integration". Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470686652.eae490. ISBN 9780470754405.

- ^ Mitchell, Glenn A.; Sanders, Bobby W. (June 1970). "Increasing the stable operating range of a Mach 2.5 inlet". NTRS. NASA. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Concorde A Designer's Life The Journey to Mach 2" Ted Talbot 2013, The History Press, ISBN 978 0 7524 8928 5. Plate 17-19

- ^ "Flying the SR-71 Blackbird" Col. Richard H. Graham, USAF(Retd.) 2008, Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0-7603-3239-9, p.141

- ^ Anderson, John D. (2009). Fundamentals of Aerodynamics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-339810-5.

- ^ Seddon, John (1985). Intake Aerodynamics. Kent, Great Britain: Collins Professional and Technical Books. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-930403-03-4.

- ^ Chima, Rodick V. (1 May 2012). Analysis of Buzz in a Supersonic Inlet (Report). NASA Glenn Research Center.