Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mach number

View on Wikipedia

This article possibly contains original research. (August 2025) |

The Mach number (M or Ma), often only Mach, (/mɑːx/; German: [max]) is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a boundary to the local speed of sound.[1][2] It is named after Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach.

where:

- M is the local Mach number,

- u is the local flow velocity with respect to the boundaries (either internal, such as an object immersed in the flow, or external, like a channel), and

- c is the speed of sound in the medium, which in air varies with the square root of the thermodynamic temperature.

By definition, at Mach 1, the local flow velocity u is equal to the speed of sound. At Mach 0.65, u is 65% of the speed of sound (subsonic), and, at Mach 1.35, u is 35% faster than the speed of sound (supersonic).

The local speed of sound, and hence the Mach number, depends on the temperature of the surrounding gas. The Mach number is primarily used to determine the approximation with which a flow can be treated as an incompressible flow. The medium can be a gas or a liquid. The boundary can be travelling in the medium, or it can be stationary while the medium flows along it, or they can both be moving, with different velocities: what matters is their relative velocity with respect to each other. The boundary can be the boundary of an object immersed in the medium, or of a channel such as a nozzle, diffuser or wind tunnel channelling the medium. As the Mach number is defined as the ratio of two speeds, it is a dimensionless quantity. If M < 0.2–0.3 and the flow is quasi-steady and isothermal, compressibility effects will be small and simplified incompressible flow equations can be used.[1][2]

Etymology

[edit]The Mach number is named after the physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach,[3] in honour of his achievements, according to a proposal by the aeronautical engineer Jakob Ackeret in 1929.[4] The word Mach is always capitalized since it derives from a proper name and since the Mach number is a dimensionless quantity rather than a unit of measure. This is also why the number comes after the word Mach. It was also known as Mach's number by Lockheed when reporting the effects of compressibility on the P-38 aircraft in 1942.[5]

Overview

[edit]

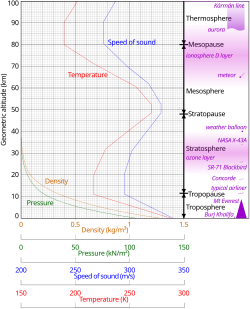

Mach number is a measure of the compressibility characteristics of fluid flow: the fluid (air) behaves under the influence of compressibility in a similar manner at a given Mach number, regardless of other variables.[6] As modeled in the International Standard Atmosphere, dry air at mean sea level, standard temperature of 15 °C (59 °F), the speed of sound is 340.3 meters per second (1,116.5 ft/s; 761.23 mph; 1,225.1 km/h; 661.49 kn).[7] The speed of sound is not a constant; in a gas, it increases proportionally to the square root of the absolute temperature, and since atmospheric temperature generally decreases with increasing altitude between sea level and 11,000 meters (36,089 ft), the speed of sound also decreases. For example, the standard atmosphere model lapses temperature to −56.5 °C (−69.7 °F) at 11,000 meters (36,089 ft) altitude, with a corresponding speed of sound (Mach 1) of 295.0 meters per second (967.8 ft/s; 659.9 mph; 1,062 km/h; 573.4 kn), 86.7% of the sea level value.

Appearance in the continuity equation

[edit]The Mach number arises naturally when the continuity equation is nondimensionalized for compressible flows. If density variations are related to pressure through the isentropic relation , the nondimensionalized continuity equation contains a prefactor . This shows that the Mach number directly measures the importance of compressibility effects in a flow. In the limit , the equation reduces to the incompressibility condition .[8]

Classification of Mach regimes

[edit]The terms subsonic and supersonic are used to refer to speeds below and above the local speed of sound, and to particular ranges of Mach values. This occurs because of the presence of a transonic regime around flight (free stream) M = 1 where approximations of the Navier-Stokes equations used for subsonic design no longer apply; the simplest explanation is that the flow around an airframe locally begins to exceed M = 1 even though the free stream Mach number is below this value.

Meanwhile, the supersonic regime is usually used to talk about the set of Mach numbers for which linearised theory may be used, where for example the (air) flow is not chemically reacting, and where heat-transfer between air and vehicle may be reasonably neglected in calculations.

| Regime | Flight speed | General plane characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mach) | (knots) | (mph) | (km/h) | (m/s) | ||

| Subsonic | <0.8 | <530 | <609 | <980 | <273 | Most often propeller-driven and commercial turbofan aircraft with high aspect-ratio (slender) wings, and rounded features like the nose and leading edges.

The subsonic speed range is that range of speeds within which, all of the airflow over an aircraft is less than Mach 1. The critical Mach number (Mcrit) is lowest free stream Mach number at which airflow over any part of the aircraft first reaches Mach 1. So the subsonic speed range includes all speeds that are less than Mcrit. |

| Transonic | 0.8–1.2 | 530–794 | 609–914 | 980–1,470 | 273–409 | Transonic aircraft nearly always have swept wings, causing the delay of drag-divergence, and often feature a design that adheres to the principles of the Whitcomb area rule.

The transonic speed range is that range of speeds within which the airflow over different parts of an aircraft is between subsonic and supersonic. So the regime of flight from Mcrit up to Mach 1.3 is called the transonic range. |

| Supersonic | 1.2–5.0 | 794–3,308 | 915–3,806 | 1,470–6,126 | 410–1,702 | The supersonic speed range is that range of speeds within which all of the airflow over an aircraft is supersonic (more than Mach 1). But airflow meeting the leading edges is initially decelerated, so the free stream speed must be slightly greater than Mach 1 to ensure that all of the flow over the aircraft is supersonic. It is commonly accepted that the supersonic speed range starts at a free stream speed greater than Mach 1.3.

Aircraft designed to fly at supersonic speeds show large differences in their aerodynamic design because of the radical differences in the behavior of flows above Mach 1. Sharp edges, thin aerofoil sections, and all-moving tailplane/canards are common. Modern combat aircraft must compromise in order to maintain low-speed handling. |

| Hypersonic | 5.0–10.0 | 3,308–6,615 | 3,806–7,680 | 6,126–12,251 | 1,702–3,403 | The X-15, at Mach 6.72, is one of the fastest crewed aircraft. Cooled nickel-titanium skin; highly integrated (due to domination of interference effects: non-linear behaviour means that superposition of results for separate components is invalid), small wings, such as those on the Mach 5 X-51A Waverider. |

| High-hypersonic | 10.0–25.0 | 6,615–16,537 | 7,680–19,031 | 12,251–30,626 | 3,403–8,508 | The NASA X-43, at Mach 9.6, is one of the fastest aircraft. Thermal control becomes a dominant design consideration. Structure must either be designed to operate hot, or be protected by special silicate tiles or similar. Chemically reacting flow can also cause corrosion of the vehicle's skin, with free-atomic oxygen featuring in very high-speed flows. Hypersonic designs are often forced into blunt configurations because of the aerodynamic heating rising with a reduced radius of curvature. |

| Re-entry speeds | >25.0 | >16,537 | >19,031 | >30,626 | >8,508 | Ablative heat shield; small or no wings; blunt shape. Russia's Avangard is claimed to reach up to Mach 27. |

High-speed flow around objects

[edit]Flight can be roughly classified in six categories:[citation needed]

| Regime | Subsonic | Transonic | Speed of sound | Supersonic | Hypersonic | Hypervelocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mach | <0.8 | 0.8–1.2 | 1.0 | 1.2–5.0 | 5.0–10.0 | >8.8 |

At transonic speeds, the flow field around the object includes both sub- and supersonic parts. The transonic period begins when first zones of M > 1 flow appear around the object. In case of an airfoil (such as an aircraft's wing), this typically happens above the wing. Supersonic flow can decelerate back to subsonic only in a normal shock; this typically happens before the trailing edge. (Fig.1a)

As the speed increases, the zone of M > 1 flow increases towards both leading and trailing edges. As M = 1 is reached and passed, the normal shock reaches the trailing edge and becomes a weak oblique shock: the flow decelerates over the shock, but remains supersonic. A normal shock is created ahead of the object, and the only subsonic zone in the flow field is a small area around the object's leading edge. (Fig.1b)

When an aircraft exceeds Mach 1 (i.e. the sound barrier), a large pressure difference is created just in front of the aircraft. This abrupt pressure difference, called a shock wave, spreads backward and outward from the aircraft in a cone shape (a so-called Mach cone). It is this shock wave that causes the sonic boom heard as a fast moving aircraft travels overhead. A person inside the aircraft will not hear this. The higher the speed, the more narrow the cone; at just over M = 1 it is hardly a cone at all, but closer to a slightly concave plane.

At fully supersonic speed, the shock wave starts to take its cone shape and flow is either completely supersonic, or (in case of a blunt object), only a very small subsonic flow area remains between the object's nose and the shock wave it creates ahead of itself. (In the case of a sharp object, there is no air between the nose and the shock wave: the shock wave starts from the nose.)

As the Mach number increases, so does the strength of the shock wave and the Mach cone becomes increasingly narrow. As the fluid flow crosses the shock wave, its speed is reduced and temperature, pressure, and density increase. The stronger the shock, the greater the changes. At high enough Mach numbers the temperature increases so much over the shock that ionization and dissociation of gas molecules behind the shock wave begin.

High-speed flow in a channel

[edit]As a flow in a channel becomes supersonic, one significant change takes place. The conservation of mass flow rate leads one to expect that contracting the flow channel would increase the flow speed (i.e. making the channel narrower results in faster air flow) and at subsonic speeds this holds true. However, once the flow becomes supersonic, the relationship of flow area and speed is reversed: expanding the channel actually increases the speed.

Calculation

[edit]When the speed of sound is known, the Mach number at which an aircraft is flying can be calculated by

where:

- M is the Mach number

- u is velocity of the moving aircraft and

- c is the speed of sound at the given altitude (more properly temperature)

and the speed of sound varies with the thermodynamic temperature as:

where:

- is the ratio of specific heat of a gas at a constant pressure to heat at a constant volume (1.4 for air)

- is the specific gas constant for air.

- is the static air temperature.

If the speed of sound is not known, Mach number may be determined by measuring the various air pressures (static and dynamic) and using the following formula that is derived from Bernoulli's equation for Mach numbers less than 1.0. Assuming air to be an ideal gas, the formula to compute Mach number in a subsonic compressible flow is:[9]

where:

- qc is impact pressure (dynamic pressure) and

- p is static pressure

- is the ratio of specific heat of a gas at a constant pressure to heat at a constant volume (1.4 for air)

The formula to compute Mach number in a supersonic compressible flow is derived from the Rayleigh supersonic pitot equation:

Calculating Mach number from pitot tube pressure

[edit]Mach number is a function of temperature and true airspeed. Aircraft flight instruments, however, operate using pressure differential to compute Mach number, not temperature.

Assuming air to be an ideal gas, the formula to compute Mach number in a subsonic compressible flow is found from Bernoulli's equation for M < 1 (above):[9]

The formula to compute Mach number in a supersonic compressible flow can be found from the Rayleigh supersonic pitot equation (above) using parameters for air:

where:

- qc is the dynamic pressure measured behind a normal shock.

As can be seen, M appears on both sides of the equation, and for practical purposes a root-finding algorithm must be used for a numerical solution (the equation is a septic equation in M2 and, though some of these may be solved explicitly, the Abel–Ruffini theorem guarantees that there exists no general form for the roots of these polynomials). It is first determined whether M is indeed greater than 1.0 by calculating M from the subsonic equation. If M is greater than 1.0 at that point, then the value of M from the subsonic equation is used as the initial condition for fixed point iteration of the supersonic equation, which usually converges very rapidly.[9] Alternatively, Newton's method can also be used.

See also

[edit]- Critical Mach number – Concept in aerodynamics

- Machmeter – Flight instrument

- Ramjet – Supersonic atmospheric jet engine

- Scramjet – Jet engine where combustion takes place in supersonic airflow

- Speed of sound – Speed of sound wave through elastic medium

- True airspeed – Speed of an aircraft relative to the air mass through which it is flying

- Orders of magnitude (speed) – Comparison of a wide range of speeds

- Fujita scale – Used to estimate wind speeds and bridges the Beaufort scale and the Mach scale

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Young, Donald F.; Munson, Bruce R.; Okiishi, Theodore H.; Huebsch, Wade W. (21 December 2010). A Brief Introduction to Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-470-59679-1. LCCN 2010038482. OCLC 667210577. OL 24479108M.

- ^ a b Graebel, William P. (19 January 2001). Engineering Fluid Mechanics (1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-56032-733-2. OCLC 1034989004. OL 9794889M.

- ^ "Ernst Mach". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved January 6, 2016.

- ^ Jakob Ackeret: Der Luftwiderstand bei sehr großen Geschwindigkeiten. Schweizerische Bauzeitung 94 (Oktober 1929), pp. 179–183. See also: N. Rott: Jakob Ackert and the History of the Mach Number. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 17 (1985), pp. 1–9.

- ^ Bodie, Warren M., The Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Widewing Publications ISBN 0-9629359-0-5.

- ^ Nancy Hall (ed.). "Mach Number". NASA.

- ^ Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Table 1, Pitman Publishing London, ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- ^ Kundu, P. J.; Cohen, I. M.; Dowling, D. R. (2012). Fluid Mechanics (5th ed.). Academic Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-12-382100-3.

- ^ a b c Olson, Wayne M. (2002). "AFFTC-TIH-99-02, Aircraft Performance Flight Testing". Air Force Flight Test Center, Edwards Air Force Base, California: United States Air Force. Archived September 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- Gas Dynamics Toolbox Calculate Mach number and normal shock wave parameters for mixtures of perfect and imperfect gases.

- NASA's page on Mach Number Interactive calculator for Mach number.

- NewByte standard atmosphere calculator and speed converter

Mach number

View on GrokipediaHistory and Etymology

Etymology

The Mach number is named after the Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach (1838–1916), who advanced the understanding of shock waves through experimental work in ballistics and optics.[3][7] In 1887, Mach collaborated with photographer Peter Salcher to produce the first photographs of shock waves using schlieren techniques, capturing the bow shock and vapor cone around a bullet traveling faster than the speed of sound and providing visual evidence of supersonic flow phenomena.[8][9] The term "Mach number" was coined in 1929 by Swiss engineer Jakob Ackeret (1898–1981) during a lecture on high-speed aerodynamics at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zurich, as a tribute to Mach's contributions.[3] Unlike other dimensionless quantities such as the Reynolds number, "Mach" is always capitalized because it originates from a proper name.[10][11]Historical Development

The concept of the Mach number emerged from pioneering experiments in the late 19th century, when Austrian physicist Ernst Mach and photographer Peter Salcher captured the first visual evidence of shock waves produced by supersonic projectiles using schlieren photography. In 1887, they fired bullets at speeds exceeding the speed of sound and photographed the conical shock waves forming ahead of the projectiles, demonstrating how air compresses and forms disturbances at high velocities.[12] These observations, published in the Annals of Physics and Chemistry, laid the groundwork for understanding compressible flow phenomena, though the dimensionless ratio now known as the Mach number was not yet formalized.[9] In the 1920s, advancements in wind tunnel testing by researchers like Jakob Ackeret and Ludwig Prandtl highlighted the effects of compressibility in airflow around airfoils at high subsonic speeds. Prandtl's theoretical work, including the Prandtl-Glauert correction derived from linearized potential flow theory, quantified how air density changes influence lift and drag as speeds approached the speed of sound, based on early wind tunnel data showing drag divergence.[13] Ackeret's experiments at the University of Göttingen further established these effects through systematic tests on airfoil models, revealing critical Mach numbers where shock waves onset, which became essential for propeller and early high-speed aircraft design.[13] During World War II in the 1940s, the Mach number gained practical urgency in military aviation, particularly with the Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter, which encountered severe compressibility issues during high-altitude dives. At speeds near Mach 0.7, shock waves formed over the wings, causing abrupt loss of control and structural stress, leading to several aircraft losses.[14] Engineers at Lockheed innovated by introducing hydraulically actuated dive recovery flaps in later models like the P-38J, which deployed to disrupt airflow and restore aileron effectiveness, allowing pilots to safely exceed previous dive limits and enhancing the aircraft's combat performance.[15] Post-World War II research accelerated supersonic exploration, culminating in the Bell X-1 program's breakthrough on October 14, 1947, when U.S. Air Force Captain Charles "Chuck" Yeager piloted the rocket-powered aircraft to Mach 1.06 at 43,000 feet, marking the first controlled flight exceeding the speed of sound in level flight.[16] This achievement, supported by data from onboard instrumentation, confirmed theoretical predictions of transonic drag rise and validated wind tunnel scaling for supersonic designs, paving the way for jet aircraft development. By the 1960s, hypersonic research pushed the Mach number's boundaries with the North American X-15 program, achieving a milestone on October 3, 1967, when U.S. Air Force Major William J. "Pete" Knight flew the X-15A-2 to Mach 6.72 (approximately 4,520 mph) at over 100,000 feet.[17] Equipped with an ablative heat shield to withstand extreme thermal loads from air friction, this flight provided critical data on hypersonic aerodynamics, including boundary layer behavior and structural heating, influencing subsequent high-speed vehicle designs.[18]Definition and Fundamentals

Definition

The Mach number is defined as the ratio of the local flow velocity relative to the medium to the speed of sound in that medium, expressed mathematically as This formulation originates from fundamental principles in compressible fluid dynamics, where it serves as a key dimensionless parameter.[19][1] As a dimensionless quantity, the Mach number facilitates scaling analyses in fluid dynamics by normalizing velocities against the local speed of sound, allowing comparisons across varying conditions such as altitude, temperature, or fluid properties without dependence on absolute units.[20] Velocities and are typically measured in meters per second (m/s) or feet per second (ft/s), but their ratio remains unitless, emphasizing its role in similarity principles for aerodynamic modeling.[4] Physically, a Mach number characterizes subsonic flow, where the incompressible flow approximation is generally valid, as disturbances propagate ahead of the object through the medium.[4] In contrast, denotes supersonic flow, in which shock waves form due to the inability of disturbances to propagate upstream, leading to abrupt changes in flow properties.[4] The Mach number also quantifies compressibility effects, with density variations becoming significant above approximately , marking the transition from negligible to pronounced thermodynamic influences in the flow.[21]Speed of Sound in Gases

The speed of sound in a gas represents the propagation velocity of small-amplitude pressure disturbances through the medium, arising from the compressibility of the gas and the resulting wave-like perturbations in pressure, density, and velocity.[22] This speed serves as a fundamental parameter in aerodynamics, particularly in defining the Mach number as the ratio of flow velocity to this characteristic speed.[23] For an ideal gas, the speed of sound is derived from the equations of continuity, momentum, and energy conservation, assuming the disturbances propagate under isentropic conditions where entropy remains constant and no heat transfer occurs. The process begins with the differential relation for pressure and density changes: , where the subscript denotes the isentropic condition. For an ideal gas, the isentropic relation follows , leading to . Substituting the ideal gas law yields , so the speed of sound is given by where is the adiabatic index (ratio of specific heats at constant pressure and volume), is the specific gas constant, and is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.[22][24] This derivation assumes infinitesimal disturbances, ensuring the process remains reversible and adiabatic.[23] In air, modeled as a diatomic ideal gas, and J/kg·K.[22][24] At standard sea-level conditions (15°C or 288 K), this yields m/s.[25] The speed depends solely on temperature for a given gas composition, scaling as , with no direct influence from pressure or density alone under ideal conditions.[26] In the Earth's troposphere, where temperature decreases with altitude at approximately 6.5 K/km, the speed of sound diminishes accordingly. At the tropopause (around 11 km altitude), the temperature drops to about -56.5°C (216.5 K), resulting in m/s.[25] This variation arises purely from the temperature lapse rate in the standard atmosphere model.[25] The speed of sound in air is also influenced by humidity and gas composition. Moist air, containing water vapor (molecular weight 18 g/mol compared to 29 g/mol for dry air), has a lower average molecular mass, which increases the effective specific gas constant and reduces density for a given temperature and pressure; although decreases slightly (from 1.4 toward 1.33 for water vapor), the net effect is a modest increase in , about 0.35% higher in fully saturated air relative to dry air at the same temperature.[27] Variations in composition, such as differing ratios of nitrogen, oxygen, or other gases, similarly alter and , affecting the speed.[26] For real gases at high temperatures or pressures, deviations from ideal behavior occur due to intermolecular forces, variable specific heats, and dissociation, requiring corrections to the simple formula. At elevated temperatures, vibrational and rotational modes of molecules increase the effective , while at high pressures, the compressibility factor departs from unity, altering . A corrected expression for calorically imperfect gases incorporates these effects, such as vibrational contributions via terms like , where K for air.[26][28]Mach Regimes

Classification of Regimes

In aerodynamics, flow regimes are classified according to the Mach number (M), which delineates boundaries where significant physical transitions occur in compressible flow behavior. These regimes guide aircraft design, propulsion systems, and performance predictions by highlighting shifts in compressibility, shock formation, and thermal effects. The standard classification, widely adopted in aeronautical engineering, divides flows into subsonic, transonic, supersonic, hypersonic, high-hypersonic, and re-entry categories based on empirical and theoretical boundaries derived from wind tunnel testing and flight data.[4][29] The subsonic regime encompasses Mach numbers less than 0.8, where incompressible flow assumptions dominate, and density variations are negligible for most practical calculations.[30] In this range, airflow remains below the local speed of sound, allowing straightforward application of potential flow theory without major corrections for compressibility.[4] The transonic regime covers 0.8 < M < 1.2, marked by mixed subsonic and supersonic regions over the body, leading to drag divergence as local sonic conditions emerge.[30] This transitional zone challenges design due to the formation of initial shock waves and boundary layer interactions.[29] For the supersonic regime, 1.2 < M < 5.0, fully supersonic flow prevails with attached shock waves that alter pressure distributions and wave propagation.[30] Oblique and normal shocks become key features, enabling efficient high-speed travel but requiring swept-wing configurations to mitigate wave drag.[4] The hypersonic regime spans 5.0 < M < 10.0, where high thermal loads from viscous dissipation and shock-layer heating dominate, often necessitating advanced materials to prevent structural failure.[4] At these speeds, the ratio of specific heats decreases, and real-gas effects begin to influence aerothermodynamics.[29] In the high-hypersonic regime, 10.0 < M < 25.0, ionization of air molecules leads to plasma formation and electromagnetic interactions, complicating sensor performance and communication.[31] This range involves non-equilibrium chemistry and dissociation, with stagnation temperatures exceeding 5000 K.[29] The re-entry regime applies to M > 25.0, characterized by extreme ablation of heat shield materials due to radiative and convective heating peaks during atmospheric interface.[31] Vehicles experience peak heating rates that can ablate tons of protective coating, as seen in orbital returns.[31] The following table summarizes these regimes, their Mach number ranges, key physical transitions, and representative historical aircraft examples that operated within or demonstrated each category:| Regime | Mach Number Range | Key Physical Transition | Historical Aircraft Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subsonic | M < 0.8 | Incompressible flow dominant | Boeing 707 (cruise M ≈ 0.8) |

| Transonic | 0.8 < M < 1.2 | Mixed sub/supersonic flow, drag divergence | Bell X-1 (approaching M = 1) |

| Supersonic | 1.2 < M < 5.0 | Shock waves present | Concorde (cruise M = 2.0) |

| Hypersonic | 5.0 < M < 10.0 | High thermal loads | North American X-15 (peak M = 6.7) |

| High-hypersonic | 10.0 < M < 25.0 | Ionization effects | DARPA HTV-2 (peak M ≈ 20) |

| Re-entry | M > 25.0 | Extreme ablation | Space Shuttle Orbiter (entry M ≈ 25) |

Flow Characteristics by Regime

In the subsonic regime, where the freestream Mach number is less than 1, flow characteristics are generally characterized by negligible compressibility effects for Mach numbers below approximately 0.3, allowing the application of incompressible flow approximations such as Bernoulli's equation to relate static pressure, dynamic pressure, and velocity along streamlines.[32][33] At higher subsonic speeds, such as the cruise Mach number of 0.85 for commercial aircraft like the Boeing 747, mild compressibility influences emerge but do not dominate, enabling efficient lift generation with conventional thick airfoils and minimal wave drag.[34] Engineering challenges in this regime primarily involve managing viscous drag and boundary layer separation rather than shock-related phenomena, facilitating stable and predictable aerodynamic performance for subsonic transport vehicles. The transonic regime, spanning freestream Mach numbers from roughly 0.8 to 1.2, features complex mixed-flow behavior with local regions of supersonic flow over parts of the vehicle, particularly on wing upper surfaces, leading to the formation of shock waves and a sharp rise in drag known as drag divergence.[35] The critical Mach number marks the onset of these supersonic pockets, where the local flow first reaches Mach 1, triggering boundary layer thickening and shock-induced separation that can cause buffet and control issues.[36] To mitigate transonic drag, design strategies like the area rule—pioneered by Richard Whitcomb—distribute the vehicle's cross-sectional area smoothly to minimize wave drag, as demonstrated in early applications such as the Boeing B-47 Stratojet bomber, which achieved improved transonic performance through fuselage-waist shaping.[35] These characteristics pose significant engineering challenges, requiring swept wings and supercritical airfoils to delay shock onset and maintain attached flow. In the supersonic regime, for freestream Mach numbers between 1 and approximately 5, the flow establishes distinct shock structures, including attached oblique shocks ahead of thin leading edges and detached bow shocks around blunt features, alongside conical disturbance patterns known as Mach cones that propagate at the Mach angle .[37] Thin airfoil theory, such as Ackeret's linear theory, becomes essential for predicting pressures and forces, emphasizing low-thickness-to-chord ratios to reduce wave drag and maintain attached shocks, as thicker profiles lead to detached shocks and higher drag penalties.[38] Aircraft like the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor, capable of sustained flight at Mach 2.25, exemplify the need for slender, highly swept designs to navigate these flows, where challenges include high skin friction, thermal loads from shock heating, and the requirement for sharp intakes to capture efficient compression without spillage. The hypersonic regime, typically defined for Mach numbers above 5, introduces pronounced viscous effects and non-ideal gas behavior, with significant heating due to the thin shock layer where dissipation converts kinetic energy into thermal energy, often exceeding adiabatic wall temperatures by factors of several hundred degrees.[39] Real gas effects, including molecular dissociation and ionization, alter thermodynamic properties like specific heat ratios and speeds of sound, necessitating multi-species models for accurate predictions.[40] Blunt body shapes are preferred for reentry vehicles, such as the Space Shuttle during atmospheric descent from orbital velocities around Mach 25, to detach the bow shock and create a thicker boundary layer that dissipates heat away from the surface, though this increases drag and requires robust heat shields like reinforced carbon-carbon panels.[41] Key engineering challenges involve balancing aerodynamic stability with thermal protection, as viscous interactions can amplify heating rates by up to 50% near stagnation points. At high-hypersonic and reentry conditions, exceeding Mach 10–15, extreme aerothermodynamic phenomena dominate, including plasma sheath formation from full air ionization behind strong shocks, which can attenuate electromagnetic signals and complicate communication, alongside widespread molecular dissociation that further modifies gas composition and transport properties.[42] These environments demand ablative thermal protection systems (TPS), where materials like phenolic resins char and erode to carry away heat, as seen in Apollo and Shuttle reentry capsules, preventing structural failure under peak heat fluxes approaching 10 MW/m².[43] The primary challenges include managing ablation-induced flow contamination, which can alter shock standoff distances and heating distributions, and ensuring TPS integrity against radiative and convective loads in nonequilibrium flows.Aerodynamic Phenomena

External Flows Around Objects

In subsonic external flows around objects such as airfoils or vehicle bodies, where the Mach number , the streamlines smoothly converge ahead of the body and diverge behind it, with no shock waves forming due to the absence of supersonic regions.[44] This regime allows for irrotational, incompressible-like approximations in many cases, though compressibility effects gradually increase lift and drag as approaches 1.[45] As the flow transitions to transonic conditions (), mixed subsonic and supersonic regions develop over the body, leading to the formation of shock waves that induce boundary layer separation and generate significant wave drag.[46] These shocks typically appear on the upper surface of airfoils, causing abrupt pressure rises and flow deceleration, which can result in drag divergence and buffet phenomena.[47] To mitigate these effects, supercritical airfoils are employed, featuring a flattened upper surface to delay shock formation and reduce wave drag by maintaining attached flow longer into the transonic regime.[48] In supersonic external flows (), the flow around objects produces attached oblique shocks at leading edges or compression corners, where the shock angle depends on the deflection and incoming Mach number, while normal shocks may occur in more blunt configurations.[49] Expansion fans arise at convex corners or trailing edges, allowing isentropic turning of the flow with gradual pressure decreases and Mach number increases across the fan.[50] The characteristic Mach angle , which defines the orientation of weak disturbances or the edges of expansion fans, is given by , originating from the limiting case of infinitesimal oblique shocks.[51] For hypersonic flows (), a strong detached bow shock forms ahead of blunt bodies, creating a thin shock layer with high entropy gradients that form an entropy layer engulfing the body and influencing boundary layer development.[52] This layer arises from non-uniform heating across the shock, leading to vorticity and reduced total pressure along streamlines. For slender bodies, Newtonian impact theory approximates surface pressures as , where is the local surface inclination, treating the flow as a particle impact neglecting centrifugal effects in the highly directional hypersonic stream. Prandtl-Meyer expansion describes the isentropic turning of supersonic flows around convex corners in external settings, such as at the shoulder of a wedge or airfoil trailing edge, where the flow deflects through a centered fan of Mach waves, increasing the Mach number and decreasing pressure without entropy loss.[50] This process is reversible and contrasts with shock-induced compression, enabling efficient flow adjustment in designs like supersonic inlets or vehicle afterbodies.[54]Internal Flows in Channels

In internal flows through channels such as ducts, nozzles, and diffusers, the Mach number governs the transition from subsonic to supersonic regimes under compressible conditions, where area changes and pressure gradients dictate flow acceleration or deceleration.[55] These one-dimensional flows are critical in propulsion systems, as the behavior shifts dramatically at Mach 1, leading to phenomena like choking and shock formation that limit mass flow and efficiency.[6] For isentropic flows in nozzles, the relationship between cross-sectional area and velocity is derived from conservation of mass and energy, yielding the differential form: where is the area, is the Mach number, is the flow velocity, and and are infinitesimal changes.[55] This equation indicates that for subsonic flow (), a converging section accelerates the flow, while for supersonic flow (), a diverging section further increases velocity; the sign reversal at highlights the throat's role in regime transitions.[1] Supersonic acceleration is achieved in converging-diverging nozzles, known as de Laval nozzles, where subsonic flow in the convergent section reaches sonic conditions (Mach 1) at the throat, becoming choked and fixing the mass flow rate regardless of downstream pressure reductions.[56] Beyond the throat, the divergent section expands the flow isentropically to supersonic Mach numbers, converting thermal energy into directed kinetic energy for efficient thrust generation.[55] Choking occurs precisely at the minimum area (throat) when the local Mach number equals 1, preventing upstream propagation of pressure disturbances and enabling stable supersonic exhaust.[6] In supersonic diffusers, which decelerate high-speed flows to recover pressure for downstream processes like combustion, shock trains form under adverse pressure gradients to compress the flow.[57] A shock train consists of a series of oblique or normal shocks that progressively slow the supersonic flow, with normal shocks causing abrupt deceleration, entropy increase, and a significant pressure rise across the wave.[58] These structures maintain the pressure recovery needed in confined channels but can lead to unstart if the backpressure exceeds design limits, displacing the train upstream.[59] The starting problem in supersonic inlets arises when the flow must transition from unstarted (subsonic) to started (supersonic) conditions, limited by the Kantrowitz criterion, which defines the maximum contraction ratio for self-starting based on isentropic flow assumptions.[60] Proposed by Kantrowitz and Donaldson in 1945, this limit ensures that the inlet can swallow the captured mass flow without forming a blocking normal shock, requiring the throat area to be sufficiently large relative to the capture area for a given freestream Mach number.[61] Below this limit, external compression or variable geometry is needed to initiate supersonic internal flow. In ramjet and scramjet engines, internal channel flows operate at Mach numbers greater than 1 to sustain high-speed propulsion, with ramjets decelerating to subsonic conditions in the combustor for heat addition and scramjets maintaining supersonic combustion throughout to avoid thermal choking.[62] These designs leverage nozzle choking for efficient air intake and shock trains in isolators to stabilize the combustor against pressure oscillations, enabling operation at flight Mach numbers from 3 to beyond 8.[63]Calculation Methods

Direct Calculation from Velocity

The Mach number is directly computed as the ratio of the local flow velocity to the speed of sound in the medium, expressed by the formula This method relies on independent measurements of velocity and thermodynamic properties to determine the local flow regime.[4][64] Flow velocity is measured using application-specific instruments that provide direct speed data. In wind tunnels or ground tests, anemometers—such as hot-wire types for low speeds or laser Doppler velocimeters for higher precision—capture relative airflow. For airborne vehicles, GPS systems deliver true airspeed by integrating position and time data, while radar tracking offers non-intrusive velocity determination for projectiles or aircraft during test flights. At low speeds, pitot-static systems can yield calibrated velocity readings suitable for initial calculations.[65][66] The step-by-step process begins with obtaining the flow velocity from the chosen instrument. The local speed of sound is then calculated from ambient temperature using , where is the specific heat ratio for dry air and J/kg·K is the gas constant. The Mach number follows by dividing by .[67] Altitude variations necessitate corrections using standardized atmospheric models to estimate temperature and other properties. The International Standard Atmosphere (ISA), aligned with the U.S. Standard Atmosphere 1976, defines temperature as a function of geopotential altitude and pressure level, with a lapse rate of -6.5 K/km up to 11 km. At 10 km, for instance, the standard temperature is 223.3 K.[68] As an illustrative case, consider a flow at 10 km altitude with m/s, K, , and J/kg·K. Here, m/s, resulting in , indicative of supersonic conditions.[4][67][68] Key error sources include temperature measurement inaccuracies, which propagate to via its square-root dependence on (a 1 K error at 223 K yields about 0.2% uncertainty in ), and non-uniform flows that cause velocity probes to sample atypical regions, potentially biasing by several percent in sheared fields. Instrument calibration and multi-point sampling mitigate these issues.[65][69][70]Pressure-Based Calculation Using Pitot Tubes

Pitot tubes provide a practical means for calculating the Mach number in compressible flows by measuring the stagnation (total) pressure and static pressure . The setup involves a Pitot probe aligned with the flow, which captures the impact pressure defined as , assuming isentropic deceleration of the flow to stagnation conditions within the tube. This method is particularly useful in flight testing and wind tunnels where direct velocity measurements are challenging.[71][72] In subsonic flows (M < 1), the relationship between pressures and Mach number derives from isentropic flow assumptions, yielding the total pressure ratio: where is the specific heat ratio. For air at standard conditions, , simplifying to: To derive this, start with the isentropic stagnation pressure equation and solve for : Substitute , so and , yielding the explicit form above. This allows direct computation of M from measured pressures without iteration. The formula assumes adiabatic, inviscid flow and is valid for subsonic conditions up to approximately M = 0.8, beyond which probe calibration errors and early shock formation degrade accuracy.[71][72][73] For supersonic flows (M > 1), a normal shock forms ahead of the Pitot tube, preventing isentropic stagnation. The Rayleigh-Pitot formula accounts for this, relating the measured total pressure behind the shock to the upstream static pressure : This equation, derived by combining normal shock relations for the pressure jump across the shock with the isentropic stagnation relation post-shock, requires an iterative numerical solution for M given the measured pressure ratio. Begin by assuming an initial M > 1, compute the right-hand side, and refine until it matches ; for , convergence is typically rapid. Standard Pitot tubes underestimate total pressure in supersonic flows due to shock losses, necessitating specialized supersonic Pitot probes designed for accurate measurement above M ≈ 1.5, often with conical tips to minimize shock interference.[72][71][74]Advanced and Modern Applications

Relativistic Mach Number

The relativistic Mach number generalizes the classical Mach number to scenarios involving high speeds comparable to the speed of light, where special relativity alters the underlying fluid dynamics. In relativistic hydrodynamics, this concept is essential for describing flows in which the rest mass energy is negligible compared to thermal or kinetic energy, such as in ultra-relativistic gases. The formulation ensures Lorentz invariance, preserving the physical meaning across reference frames. For an ultra-relativistic ideal gas, the equation of state is , where is the pressure and is the total energy density. The relativistic speed of sound is derived from perturbations in the relativistic Euler equations as , yielding . This value arises because the adiabatic index for such gases, and the sound speed reflects the causal structure limited by the speed of light. The relativistic Mach number is defined as the ratio of the flow speed to this sound speed, but adjusted for relativistic effects using the fluid four-velocity , where and . A Lorentz-invariant expression incorporates the specific enthalpy , where is the rest-mass density, leading to the sound speed in general cases. The Mach number takes the form derived from the dispersion relation of linearized relativistic magnetohydrodynamic equations around a fluid interface. Here, the square root term accounts for the boost in the lab frame, ensuring invariance. When the flow velocity is interpreted via proper velocity , ; however, due to the relativistic cap on three-velocity, approaches a limit of in the ultra-relativistic regime for the three-velocity ratio, contrasting with the classical case where is possible. This framework applies to astrophysical jets, such as those from active galactic nuclei, where relativistic outflows propagate at speeds exceeding , enabling efficient particle acceleration through internal shocks with . In particle accelerators, the concept describes beam-plasma interactions, where relativistic particle bunches exceed the sound speed in surrounding relativistic gases, facilitating wakefield acceleration. Unlike classical supersonic flows, strict relativistic treatments preclude infinite Mach numbers and sharp shock discontinuities; instead, transitions across "shocks" are gradual, smoothed by the finite mean free path and high Lorentz factors, leading to extended precursor regions.Hypersonic and Spaceflight Applications

Hypersonic vehicles operate at Mach numbers exceeding 5, where aerodynamic heating and propulsion challenges intensify, often employing waverider designs that leverage shock waves for lift and compression. The Boeing X-51A Waverider, an unmanned scramjet demonstrator, achieved sustained flight at Mach 5.1 during its final test in 2013, marking the longest air-breathing hypersonic flight at over 210 seconds powered by JP-7 fuel.[75][76] These vehicles rely on advanced thermal protection systems, such as ceramic matrix composites and carbon-carbon composites, to withstand surface temperatures exceeding 1,600°C from frictional heating.[77][78] Post-2020 developments have advanced both sustained hypersonic and quiet supersonic capabilities. NASA's X-59 QueSST aircraft, designed for the Quesst mission, targets Mach 1.4 cruises at 55,000 feet to produce sonic thumps below 75 decibels, enabling overland supersonic flight without disruptive booms; it completed its first flight on October 28, 2025, beginning the initial test campaign.[79][80][81] Conceptual efforts like the DARPA-backed Lockheed Martin SR-72 envision unmanned hypersonic reconnaissance at Mach 6 using turbine-based combined-cycle engines for acceleration from standstill.[82] In spaceflight, re-entry profiles at extreme Mach numbers demand precise trajectory management to mitigate heating. For instance, SpaceX's Starship spacecraft encounters Mach 25+ during orbital re-entry, where peak heating scales approximately as , with heat flux proportional to the square root of atmospheric density and the cube of velocity, often peaking at altitudes around 60 km.[83][84] This formula, derived from stagnation-point heating models, underscores the need for robust heat shields to protect against fluxes up to several MW/m². Military applications leverage hypersonic glide vehicles for rapid, maneuverable strikes. Russia's Avangard system, deployed in 2019 atop SS-19 missiles, achieves Mach 27 while gliding at altitudes over 50 km, carrying nuclear warheads up to two megatons and evading defenses through unpredictable trajectories.[85][86] The U.S. Air Force's AGM-183A ARRW, tested in 2023 from B-52 bombers, reaches Mach 5+ speeds with boost-glide capabilities. The program faced challenges like shroud separation, leading to near-cancellation in 2024, but was revived in 2025 with $387.1 million in funding requested for FY2026 procurement.[87][88][89] Key challenges in these regimes include material degradation and flight control at Mach >10, where carbon-carbon composites face oxidation limits above 2,000°C, necessitating ultra-high-temperature ceramics for longevity.[78] Control systems must counter extreme aerodynamic sensitivities, with plasma sheaths disrupting communications and requiring advanced guidance for stability during maneuvers.[90][91]References

- https://ntrs.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/api/citations/19660012440/downloads/19660012440.pdf

.jpg/250px-FA-18_Hornet_breaking_sound_barrier_(7_July_1999).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-FA-18_Hornet_breaking_sound_barrier_(7_July_1999).jpg)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {M} ={\sqrt {{\frac {2}{\gamma -1}}\left[\left({\frac {q_{c}}{p}}+1\right)^{\frac {\gamma -1}{\gamma }}-1\right]}}\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b6cfb0b14f5726032a386928f8312725a3325c4c)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {p_{t}}{p}}=\left[{\frac {\gamma +1}{2}}\mathrm {M} ^{2}\right]^{\frac {\gamma }{\gamma -1}}\cdot \left[{\frac {\gamma +1}{1-\gamma +2\gamma \,\mathrm {M} ^{2}}}\right]^{\frac {1}{\gamma -1}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e40925c7d73812aaeb7be0541fb045abfe268c54)

![{\displaystyle \mathrm {M} ={\sqrt {5\left[\left({\frac {q_{c}}{p}}+1\right)^{\frac {2}{7}}-1\right]}}\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dbbe331c3f8c63b187b0a3a3fc23580e4cb2ac55)