Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Valinomycin

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

cyclo[N-oxa-D-alanyl-D-valyl-N-oxa-L-valyl-D-valyl-N-oxa-D-alanyl-D-valyl-N-oxa-L-valyl-L-valyl-N-oxa-L-alanyl-L-valyl-N-oxa-L-valyl-L-valyl]

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.270 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2811 2588 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C54H90N6O18 | |

| Molar mass | 1111.338 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Melting point | 190 °C (374 °F; 463 K) |

| Solubility | Methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, petrol-ether, dichloromethane |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 220 nm |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Neurotoxicant |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H300, H310 | |

| P262, P264, P270, P280, P301+P310, P302+P350, P310, P321, P322, P330, P361, P363, P405, P501 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

4 mg/kg (oral, rat)[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

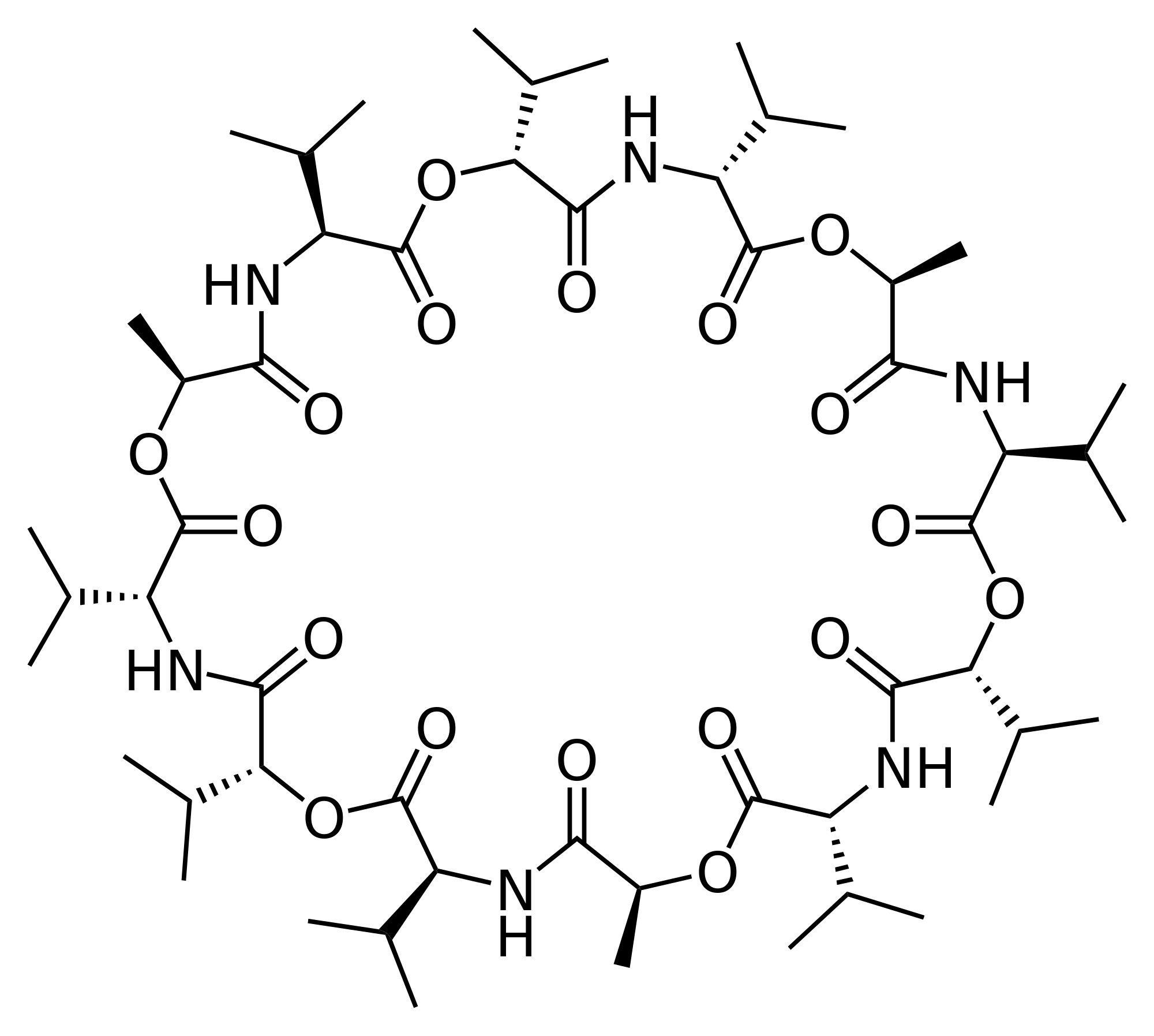

Valinomycin is a naturally occurring dodecadepsipeptide used in the transport of potassium and as an antibiotic. Valinomycin is obtained from the cells of several Streptomyces species, S. fulvissimus being a notable one.

It is a member of the group of natural neutral ionophores because it does not have a residual charge. It consists of the enantiomers D- and L-valine (Val), D-alpha-hydroxyisovaleric acid, and L-lactic acid. Structures are alternately bound via amide and ester bridges. Valinomycin is highly selective for potassium ions over sodium ions within the cell membrane.[2] It functions as a potassium-specific transporter and facilitates the movement of potassium ions through lipid membranes "down" the electrochemical potential gradient.[3] The stability constant K for the potassium-valinomycin complex is nearly 100,000 times larger than that of the sodium-valinomycin complex.[4] This difference is important for maintaining the selectivity of valinomycin for the transport of potassium ions (and not sodium ions) in biological systems.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[5]

Structure

[edit]Valinomycin is a dodecadepsipeptide, that is, it is made of twelve alternating amino acids and esters to form a macrocyclic molecule. The twelve carbonyl groups are essential for the binding of metal ions, and also for solvation in polar solvents. The isopropyl and methyl groups are responsible for solvation in nonpolar solvents. [6] Along with its shape and size this molecular duality is the main reason for its binding properties. K ions must give up their water of hydration to pass through the pore. K+ ions are octahedrally coordinated in a square bipyramidal geometry by 6 carbonyl bonds from Val. In this space of 1.33 Angstrom, Na+ with its 0.95 Angstrom radius, is significantly smaller than the channel, meaning that Na+ cannot form ionic bonds with the amino acids of the pore at equivalent energy as those it gives up with the water molecules. This leads to a 10,000x selectivity for K+ ions over Na+. For polar solvents, valinomycin will mainly expose the carbonyls to the solvent and in nonpolar solvents the isopropyl groups are located predominantly on the exterior of the molecule. This conformation changes when valinomycin is bound to a potassium ion. The molecule is "locked" into a conformation with the isopropyl groups on the exterior [Citation Needed]. It is not actually locked into configuration because the size of the molecule makes it highly flexible, but the potassium ion gives some degree of coordination to the macromolecule.

Applications

[edit]Valinomycin was recently reported to be the most potent agent against severe acute respiratory-syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in infected Vero E6 cells.[7] Valinomycin has been shown to inhibit completely vaccinia virus in cell based assay in human cell line.[8]

Valinomycin acts as a nonmetallic isoforming agent in potassium selective electrodes.[9][10]

This ionophore is used to study membrane vesicles, where it may be selectively applied by experimental design to reduce or eliminate the electrochemical gradient across a membrane.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "ChemIDplus - 2001-95-8 - FCFNRCROJUBPLU-DNDCDFAISA-N - Valinomycin - Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". TOXNET. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015.

- ^ Lars, Rose, Jenkins ATA (2007). "The effect of the ionophore valinomycin on biomimetic solid supported lipid DPPTE/EPC membranes". Bioelectrochemistry. 70 (2): 387–393. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2006.05.009. PMID 16875886.

- ^ Cammann K (1985). "Ion-selective bulk membranes as models". Top. Curr. Chem. Topics in Current Chemistry. 128: 219–258. doi:10.1007/3-540-15136-2_8. ISBN 978-3-540-15136-4.

- ^ Rose MC, Henkens RW (1974). "Stability of sodium and potassium complexes of valinomycin". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 372 (2): 426–435. doi:10.1016/0304-4165(74)90204-9.

- ^ "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Thompson M, Krull UJ (1982). "The electroanalytical response of the bilayer lipid membrane to valinomycin: membrane cholesterol content". Anal. Chim. Acta. 141: 33–47. Bibcode:1982AcAC..141...33T. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(01)95308-5.

- ^ Zhang D, Ma Z, Chen H, Lu Y, Chen X (October 2020). "Valinomycin as a potential antiviral agent against coronaviruses: A review". Biomedical Journal. 43 (5): 414–423. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2020.08.006. ISSN 2319-4170. PMC 7417921. PMID 33012699.

- ^ Witwit H, Cubitt B, Khafaji R, Castro EM, Goicoechea M, Lorenzo MM, Blasco R, Martinez-Sobrido L, de la Torre JC (January 2025). "Repurposing Drugs for Synergistic Combination Therapies to Counteract Monkeypox Virus Tecovirimat Resistance". Viruses. 17 (1): 92. doi:10.3390/v17010092. ISSN 1999-4915. PMC 11769280.

- ^ Safiulina D, Veksler V, Zharkovsky A, Kaasik A (2006). "Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential is associated with increase in mitochondrial volume: physiological role in neurones". J. Cell. Physiol. 206 (2): 347–353. doi:10.1002/jcp.20476. PMID 16110491. S2CID 34918061.

- ^ "Potassium ionophore Bulletin" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

External links

[edit]- Chemical Safety Regulations from New Jersey Department of Health

- Health information on Scorecard Archived 2005-05-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Valinomycin from Fermentek

- Valinomycin in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)