Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Amphetamine

View on Wikipedia

Amphetamine[note 2] is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity; it is also used to treat binge eating disorder in the form of its inactive prodrug lisdexamfetamine. Amphetamine was discovered as a chemical in 1887 by Lazăr Edeleanu, and then as a drug in the late 1920s. It exists as two enantiomers:[note 3] levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine. Amphetamine properly refers to a specific chemical, the racemic free base, which is equal parts of the two enantiomers in their pure amine forms. The term is frequently used informally to refer to any combination of the enantiomers, or to either of them alone. Historically, it has been used to treat nasal congestion and depression. Amphetamine is also used as an athletic performance enhancer and cognitive enhancer, and recreationally as an aphrodisiac and euphoriant. It is a prescription drug in many countries, and unauthorized possession and distribution of amphetamine are often tightly controlled due to the significant health risks associated with recreational use.[sources 1]

The first amphetamine pharmaceutical was Benzedrine, a brand which was used to treat a variety of conditions. Pharmaceutical amphetamine is prescribed as racemic amphetamine, Adderall,[note 4] dextroamphetamine, or the inactive prodrug lisdexamfetamine. Amphetamine increases monoamine and excitatory neurotransmission in the brain, with its most pronounced effects targeting the norepinephrine and dopamine neurotransmitter systems.[sources 2]

At therapeutic doses, amphetamine causes emotional and cognitive effects such as euphoria, change in desire for sex, increased wakefulness, and improved cognitive control. It induces physical effects such as improved reaction time, fatigue resistance, decreased appetite, elevated heart rate, and increased muscle strength. Larger doses of amphetamine may impair cognitive function and induce rapid muscle breakdown. Addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use, but is unlikely to occur from long-term medical use at therapeutic doses. Very high doses can result in psychosis (e.g., hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia) which rarely occurs at therapeutic doses even during long-term use. Recreational doses are generally much larger than prescribed therapeutic doses and carry a far greater risk of serious side effects.[sources 3]

Amphetamine belongs to the phenethylamine class. It is also the parent compound of its own structural class, the substituted amphetamines,[note 5] which includes prominent substances such as bupropion, cathinone, MDMA, and methamphetamine. As a member of the phenethylamine class, amphetamine is also chemically related to the naturally occurring trace amine neuromodulators, specifically phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine, both of which are produced within the human body. Phenethylamine is the parent compound of amphetamine, while N-methylphenethylamine is a positional isomer of amphetamine that differs only in the placement of the methyl group.[sources 4]

Uses

[edit]Medical

[edit]Amphetamine is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, obesity, and, in the form of lisdexamfetamine, binge eating disorder.[1][35][36] It is sometimes prescribed off-label for its past medical indications, particularly for depression and chronic pain.[1][51]

ADHD

[edit]Long-term amphetamine exposure at sufficiently high doses in some animal species is known to produce abnormal dopamine system development or nerve damage,[52][53] but, in humans with ADHD, long-term use of pharmaceutical amphetamines at therapeutic doses appears to improve brain development and nerve growth.[54][55][56] Reviews of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD, and improves function in several parts of the brain, such as the right caudate nucleus of the basal ganglia.[54][55][56]

Reviews of clinical stimulant research have established the safety and effectiveness of long-term continuous amphetamine use for the treatment of ADHD.[44][57][58] Randomized controlled trials of continuous stimulant therapy for the treatment of ADHD spanning 2 years have demonstrated treatment effectiveness and safety.[44][57] Two reviews have indicated that long-term continuous stimulant therapy for ADHD is effective for reducing the core symptoms of ADHD (i.e., hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity), enhancing quality of life and academic achievement, and producing improvements in a large number of functional outcomes[note 6] across 9 categories of outcomes related to academics, antisocial behavior, driving, non-medicinal drug use, obesity, occupation, self-esteem, service use (i.e., academic, occupational, health, financial, and legal services), and social function.[44][58] Additionally, a 2024 meta-analytic systematic review reported moderate improvements in quality of life when amphetamine treatment is used for ADHD.[60] One review highlighted a nine-month randomized controlled trial of amphetamine treatment for ADHD in children that found an average increase of 4.5 IQ points, continued increases in attention, and continued decreases in disruptive behaviors and hyperactivity.[57] Another review indicated that, based upon the longest follow-up studies conducted to date, lifetime stimulant therapy that begins during childhood is continuously effective for controlling ADHD symptoms and reduces the risk of developing a substance use disorder as an adult.[44]

Models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems;[61] these functional impairments involve impaired dopamine neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic projection and norepinephrine neurotransmission in the noradrenergic projections from the locus coeruleus to the prefrontal cortex.[61] Stimulants like methylphenidate and amphetamine are effective in treating ADHD because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[26][61][62] Approximately 80% of those who use these stimulants see improvements in ADHD symptoms.[63] Children with ADHD who use stimulant medications generally have better relationships with peers and family members, perform better in school, are less distractible and impulsive, and have longer attention spans.[64][65] The Cochrane reviews[note 7] on the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults with pharmaceutical amphetamines stated that short-term studies have demonstrated that these drugs decrease the severity of symptoms, but they have higher discontinuation rates than non-stimulant medications due to their adverse side effects.[67][68] However, a 2025 meta-analytic systematic review of 113 randomized controlled trials found that stimulant medications were the only intervention with robust short-term efficacy, and were associated with lower all-cause treatment discontinuation rates than non-stimulant medications (e.g., atomoxetine).[note 8][69] A Cochrane review on the treatment of ADHD in children with tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome indicated that stimulants in general do not make tics worse, but high doses of dextroamphetamine could exacerbate tics in some individuals.[70]

Binge eating disorder

[edit]Binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent and persistent episodes of compulsive binge eating.[71] These episodes are often accompanied by marked distress and a feeling of loss of control over eating.[71] The pathophysiology of BED is not fully understood, but it is believed to involve dysfunctional dopaminergic reward circuitry along the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical loop.[72][73] As of July 2024, lisdexamfetamine is the only USFDA- and TGA-approved pharmacotherapy for BED.[36][74] Evidence suggests that lisdexamfetamine's treatment efficacy in BED is underpinned at least in part by a psychopathological overlap between BED and ADHD, with the latter conceptualized as a cognitive control disorder that also benefits from treatment with lisdexamfetamine.[72][73]

Lisdexamfetamine's therapeutic effects for BED primarily involve direct action in the central nervous system after conversion to its pharmacologically active metabolite, dextroamphetamine.[74] Centrally, dextroamphetamine increases neurotransmitter activity of dopamine and norepinephrine in prefrontal cortical regions that regulate cognitive control of behavior.[72][74] Similar to its therapeutic effect in ADHD, dextroamphetamine enhances cognitive control and may reduce impulsivity in patients with BED by enhancing the cognitive processes responsible for overriding prepotent feeding responses that precede binge eating episodes.[72][76][77] Dextroamphetamine is also a full agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a G-protein coupled receptor that regulates monoaminergic systems in the brain;[78][79] Activation of TAAR1 may restore impaired dopaminergic signaling in the prefrontal cortex and thereby correct deficits in inhibitory control associated with binge eating behaviors.[79] Beyond central nervous system mechanisms, peripheral actions of dextroamphetamine may also contribute to its treatment efficacy in BED. Through noradrenergic signaling pathways, dextroamphetamine triggers lipolysis in adipose fat cells, thereby prompting the release of triglycerides into blood plasma to be utilized as a fuel substrate.[73][80] Moreover, dextroamphetamine induces synthesis of the cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), a peptide neurotransmitter that regulates food intake.[81] Within the hypothalamus, CART interacts with leptin signaling pathways to promote appetite suppression.[81] Dextroamphetamine also activates TAAR1 in peripheral organs along the gastrointestinal tract that are involved in the regulation of food intake and body weight.[79][75] Together, these actions confer an anorexigenic effect that promotes satiety in response to feeding and may decrease binge eating as a secondary effect.[77][75] While lisdexamfetamine's anorexigenic effects contribute to its efficacy in BED, evidence indicates that the enhancement of cognitive control is necessary and sufficient for addressing the disorder's underlying psychopathology.[72][82] This view is supported by the failure of anti-obesity medications and other appetite suppressants to significantly reduce BED symptom severity, despite their capacity to induce weight loss.[82]

Medical reviews of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that lisdexamfetamine, at doses between 50–70 mg, is safe and effective for the treatment of moderate-to-severe BED in adults.[sources 5] These reviews suggest that lisdexamfetamine is persistently effective at treating BED and is associated with significant reductions in the number of binge eating days and binge eating episodes per week.[sources 5] Furthermore, a meta-analytic systematic review highlighted an open-label, 12-month extension safety and tolerability study that reported lisdexamfetamine remained effective at reducing the number of binge eating days for the duration of the study.[77] In addition, both a review and a meta-analytic systematic review found lisdexamfetamine to be superior to placebo in several secondary outcome measures, including persistent binge eating cessation, reduction of obsessive-compulsive related binge eating symptoms, reduction of body-weight, and reduction of triglycerides.[73][77] Lisdexamfetamine, like all pharmaceutical amphetamines, has direct appetite suppressant effects that may be therapeutically useful in both BED and its comorbidities.[36][77] Based on reviews of neuroimaging studies involving BED-diagnosed participants, therapeutic neuroplasticity in dopaminergic and noradrenergic pathways from long-term use of lisdexamfetamine may be implicated in lasting improvements in the regulation of eating behaviors that are observed.[36][74][77]

Narcolepsy

[edit]Narcolepsy is a chronic sleep-wake disorder that is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.[84] Patients with narcolepsy are diagnosed as either type 1 or type 2, with only the former presenting cataplexy symptoms.[85] Type 1 narcolepsy results from the loss of approximately 70,000 orexin-releasing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, leading to significantly reduced cerebrospinal orexin levels;[16][86] this reduction is a diagnostic biomarker for type 1 narcolepsy.[85] Lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons innervate every component of the ascending reticular activating system (ARAS), which includes noradrenergic, dopaminergic, histaminergic, and serotonergic nuclei that promote wakefulness.[86][87]

Amphetamine's therapeutic mode of action in narcolepsy primarily involves increasing monoamine neurotransmitter activity in the ARAS.[16][88][89] This includes noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus, dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, histaminergic neurons in the tuberomammillary nucleus, and serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus.[87][89] Dextroamphetamine, the more dopaminergic enantiomer of amphetamine, is particularly effective at promoting wakefulness because dopamine release has the greatest influence on cortical activation and cognitive arousal, relative to other monoamines.[16][90] In contrast, levoamphetamine may have a greater effect on cataplexy, a symptom more sensitive to the effects of norepinephrine and serotonin.[16] Noradrenergic and serotonergic nuclei in the ARAS are involved in the regulation of the REM sleep cycle and function as "REM-off" cells, with amphetamine's effect on norepinephrine and serotonin contributing to the suppression of REM sleep and a possible reduction of cataplexy at high doses.[16][85][87]

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) 2021 clinical practice guideline conditionally recommends dextroamphetamine for the treatment of both type 1 and type 2 narcolepsy.[91] Treatment with pharmaceutical amphetamines is generally less preferred relative to other stimulants (e.g., modafinil) and is considered a third-line treatment option.[47][92][93] Medical reviews indicate that amphetamine is safe and effective for the treatment of narcolepsy.[16][47][91] Amphetamine appears to be most effective at improving symptoms associated with hypersomnolence, with three reviews finding clinically significant reductions in daytime sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy.[16][47][91] Additionally, these reviews suggest that amphetamine may dose-dependently improve cataplexy symptoms.[16][47][91] However, the quality of evidence for these findings is low and is consequently reflected in the AASM's conditional recommendation for dextroamphetamine as a treatment option for narcolepsy.[91]

Enhancing performance

[edit]Cognitive performance

[edit]In 2015, a systematic review and a meta-analysis of high quality clinical trials found that, when used at low (therapeutic) doses, amphetamine produces modest yet unambiguous improvements in cognition, including working memory, long-term episodic memory, inhibitory control, and some aspects of attention, in normal healthy adults;[94][95] these cognition-enhancing effects of amphetamine are known to be partially mediated through the indirect activation of both dopamine D1 receptor and α2-adrenergic receptor in the prefrontal cortex.[26][94] A systematic review from 2014 found that low doses of amphetamine also improve memory consolidation, in turn leading to improved recall of information.[96] Therapeutic doses of amphetamine also enhance cortical network efficiency, an effect which mediates improvements in working memory in all individuals.[26][97] Amphetamine and other ADHD stimulants also improve task saliency (motivation to perform a task) and increase arousal (wakefulness), in turn promoting goal-directed behavior.[26][98][99] Stimulants such as amphetamine can improve performance on difficult and boring tasks and are used by some students as a study and test-taking aid.[26][99][100] Based upon studies of self-reported illicit stimulant use, 5–35% of college students use diverted ADHD stimulants, which are primarily used for enhancement of academic performance rather than as recreational drugs.[101][102][103] However, high amphetamine doses that are above the therapeutic range can interfere with working memory and other aspects of cognitive control.[26][99]

Physical performance

[edit]Amphetamine is used by some athletes for its psychological and athletic performance-enhancing effects, such as increased endurance and alertness;[27][40] however, non-medical amphetamine use is prohibited at sporting events that are regulated by collegiate, national, and international anti-doping agencies.[104][105] In healthy people at oral therapeutic doses, amphetamine has been shown to increase muscle strength, acceleration, athletic performance in anaerobic conditions, and endurance (i.e., it delays the onset of fatigue), while improving reaction time.[27][106][107] Amphetamine improves endurance and reaction time primarily through reuptake inhibition and release of dopamine in the central nervous system.[106][107][108] Amphetamine and other dopaminergic drugs also increase power output at fixed levels of perceived exertion by overriding a "safety switch", allowing the core temperature limit to increase in order to access a reserve capacity that is normally off-limits.[107][109][110] At therapeutic doses, the adverse effects of amphetamine do not impede athletic performance;[27][106] however, at much higher doses, amphetamine can induce effects that severely impair performance, such as rapid muscle breakdown and elevated body temperature.[28][106]

Recreational

[edit]Amphetamine, specifically the more dopaminergic dextrorotatory enantiomer (dextroamphetamine), is also used recreationally as a euphoriant and aphrodisiac, and like other amphetamines; is used as a club drug for its energetic and euphoric high. Dextroamphetamine (d-amphetamine) is considered to have a high potential for misuse in a recreational manner since individuals typically report feeling euphoric, more alert, and more energetic after taking the drug.[111][112][113] A notable part of the 1960s mod subculture in the UK was recreational amphetamine use, which was used to fuel all-night dances at clubs like Manchester's Twisted Wheel. Newspaper reports described dancers emerging from clubs at 5 a.m. with dilated pupils.[114] Mods used the drug for stimulation and alertness, which they viewed as different from the intoxication caused by alcohol and other drugs.[114] Dr. Andrew Wilson argues that for a significant minority, "amphetamines symbolised the smart, on-the-ball, cool image" and that they sought "stimulation not intoxication [...] greater awareness, not escape" and "confidence and articulacy" rather than the "drunken rowdiness of previous generations."[114] Dextroamphetamine's dopaminergic (rewarding) properties affect the mesocorticolimbic circuit; a group of neural structures responsible for incentive salience (i.e., "wanting"; desire or craving for a reward and motivation), positive reinforcement and positively-valenced emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure.[115] Large recreational doses of dextroamphetamine may produce symptoms of dextroamphetamine overdose.[113] Recreational users sometimes open dexedrine capsules and crush the contents in order to insufflate (snort) it or subsequently dissolve it in water and inject it.[113] Immediate-release formulations have higher potential for abuse via insufflation (snorting) or intravenous injection due to a more favorable pharmacokinetic profile and easy crushability (especially tablets).[116][117] Injection into the bloodstream can be dangerous because insoluble fillers within the tablets can block small blood vessels.[113] Chronic overuse of dextroamphetamine can lead to severe drug dependence, resulting in withdrawal symptoms when drug use stops.[113]

Contraindications

[edit]According to the International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA),[note 9] amphetamine is contraindicated in people with a history of drug abuse,[note 10] cardiovascular disease, severe agitation, or severe anxiety.[35][28][119] It is also contraindicated in individuals with advanced arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), glaucoma (increased eye pressure), hyperthyroidism (excessive production of thyroid hormone), or moderate to severe hypertension.[35][28][119] These agencies indicate that people who have experienced allergic reactions to other stimulants or who are taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) should not take amphetamine,[35][28][119] although safe concurrent use of amphetamine and monoamine oxidase inhibitors has been documented.[120][121] These agencies also state that anyone with anorexia nervosa, bipolar disorder, depression, hypertension, liver or kidney problems, mania, psychosis, Raynaud's phenomenon, seizures, thyroid problems, tics, or Tourette syndrome should monitor their symptoms while taking amphetamine.[28][119] Evidence from human studies indicates that therapeutic amphetamine use does not cause developmental abnormalities in the fetus or newborns (i.e., it is not a human teratogen), but amphetamine abuse does pose risks to the fetus.[119] Amphetamine has also been shown to pass into breast milk, so the IPCS and the FDA advise mothers to avoid breastfeeding when using it.[28][119] Due to the potential for reversible growth impairments,[note 11] the FDA advises monitoring the height and weight of children and adolescents prescribed an amphetamine pharmaceutical.[28]

Adverse effects

[edit]The adverse side effects of amphetamine are many and varied, and the amount of amphetamine used is the primary factor in determining the likelihood and severity of adverse effects.[28][40] Amphetamine products such as Adderall, Dexedrine, and their generic equivalents are currently approved by the U.S. FDA for long-term therapeutic use.[37][28] Recreational use of amphetamine generally involves much larger doses, which have a greater risk of serious adverse drug effects than dosages used for therapeutic purposes.[40]

Physical

[edit]Cardiovascular side effects can include hypertension or hypotension from a vasovagal response, Raynaud's phenomenon (reduced blood flow to the hands and feet), and tachycardia (increased heart rate).[28][40][122] Sexual side effects in males may include erectile dysfunction, frequent erections, or prolonged erections.[28] Gastrointestinal side effects may include abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and nausea.[1][28][123] Other potential physical side effects include appetite loss, blurred vision, dry mouth, excessive grinding of the teeth, nosebleed, profuse sweating, rhinitis medicamentosa (drug-induced nasal congestion), reduced seizure threshold, tics (a type of movement disorder), and weight loss.[sources 6] Dangerous physical side effects are rare at typical pharmaceutical doses.[40]

Amphetamine stimulates the medullary respiratory centers, producing faster and deeper breaths.[40] In a normal person at therapeutic doses, this effect is usually not noticeable, but when respiration is already compromised, it may be evident.[40] Amphetamine also induces contraction in the urinary bladder sphincter, the muscle which controls urination, which can result in difficulty urinating.[40] This effect can be useful in treating bed wetting and loss of bladder control.[40] The effects of amphetamine on the gastrointestinal tract are unpredictable.[40] If intestinal activity is high, amphetamine may reduce gastrointestinal motility (the rate at which content moves through the digestive system);[40] however, amphetamine may increase motility when the smooth muscle of the tract is relaxed.[40] Amphetamine also has a slight analgesic effect and can enhance the pain relieving effects of opioids.[1][40]

FDA-commissioned studies from 2011 indicate that in children, young adults, and adults there is no association between serious adverse cardiovascular events (sudden death, heart attack, and stroke) and the medical use of amphetamine or other ADHD stimulants.[sources 7] These findings were subsequently corroborated by a 2022 meta-analysis that sampled nearly four million participants, which found no association between therapeutic use of amphetamine and the development of cardiovascular disease in any age group.[129] However, amphetamine pharmaceuticals are contraindicated in individuals with preexisting cardiovascular disease.[sources 8]

Psychological

[edit]At normal therapeutic doses, the most common psychological side effects of amphetamine include increased alertness, apprehension, concentration, initiative, self-confidence and sociability, mood swings (elated mood followed by mildly depressed mood), insomnia or wakefulness, and decreased sense of fatigue.[28][40] Less common side effects include anxiety, change in libido, grandiosity, irritability, repetitive or obsessive behaviors, and restlessness;[sources 9] these effects depend on the user's personality and current mental state.[40] Amphetamine psychosis (e.g., delusions and paranoia) can occur in heavy users.[28][41][42] Although very rare, this psychosis can also occur at therapeutic doses during long-term therapy.[28][42][43] According to the FDA, "there is no systematic evidence" that stimulants produce aggressive behavior or hostility.[28]

Amphetamine has also been shown to produce a conditioned place preference in humans taking therapeutic doses,[67][131] meaning that individuals acquire a preference for spending time in places where they have previously used amphetamine.[131][132]

Reinforcement disorders

[edit]Addiction

[edit]| Addiction and dependence glossary[132][133][134] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Transcription factor glossary | |

|---|---|

| |

Addiction is a serious risk with heavy recreational amphetamine use, but is unlikely to occur from long-term medical use at therapeutic doses;[45][46][47] in fact, lifetime stimulant therapy for ADHD that begins during childhood reduces the risk of developing substance use disorders as an adult.[44] Pathological overactivation of the mesolimbic pathway, a dopamine pathway that connects the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, plays a central role in amphetamine addiction.[141][142] Individuals who frequently self-administer high doses of amphetamine have a high risk of developing an amphetamine addiction, since chronic use at high doses gradually increases the level of accumbal ΔFosB, a "molecular switch" and "master control protein" for addiction.[133][143][144] Once nucleus accumbens ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it begins to increase the severity of addictive behavior (i.e., compulsive drug-seeking) with further increases in its expression.[143][145] While there are currently no effective drugs for treating amphetamine addiction, regularly engaging in sustained aerobic exercise appears to reduce the risk of developing such an addiction.[146][147] Exercise therapy improves clinical treatment outcomes and may be used as an adjunct therapy with behavioral therapies for addiction.[146][148][sources 10]

Biomolecular mechanisms

[edit]Chronic use of amphetamine at excessive doses causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic projection, which arise through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms.[144][149][150] The most important transcription factors[note 12] that produce these alterations are Delta FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (ΔFosB), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB).[144] ΔFosB is the most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because ΔFosB overexpression (i.e., an abnormally high level of gene expression which produces a pronounced gene-related phenotype) in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient[note 13] for many of the neural adaptations and regulates multiple behavioral effects (e.g., reward sensitization and escalating drug self-administration) involved in addiction.[133][143][144] Once ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it induces an addictive state that becomes increasingly more severe with further increases in ΔFosB expression.[133][143] It has been implicated in addictions to alcohol, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine, propofol, and substituted amphetamines, among others.[sources 11]

ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a histone methyltransferase enzyme, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and inhibit increases in its expression.[133][144][154] Sufficiently overexpressing ΔJunD in the nucleus accumbens with viral vectors can completely block many of the neural and behavioral alterations seen in chronic drug abuse (i.e., the alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[144] Similarly, accumbal G9a hyperexpression results in markedly increased histone 3 lysine residue 9 dimethylation (H3K9me2) and blocks the induction of ΔFosB-mediated neural and behavioral plasticity by chronic drug use,[sources 12] which occurs via H3K9me2-mediated repression of transcription factors for ΔFosB and H3K9me2-mediated repression of various ΔFosB transcriptional targets (e.g., CDK5).[144][154][155] ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[145][144][158] Since both natural rewards and addictive drugs induce the expression of ΔFosB (i.e., they cause the brain to produce more of it), chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological state of addiction.[145][144] Consequently, ΔFosB is the most significant factor involved in both amphetamine addiction and amphetamine-induced sexual addictions, which are compulsive sexual behaviors that result from excessive sexual activity and amphetamine use.[145][159][160] These sexual addictions are associated with a dopamine dysregulation syndrome which occurs in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs.[145][158]

The effects of amphetamine on gene regulation are both dose- and route-dependent.[150] Most of the research on gene regulation and addiction is based upon animal studies with intravenous amphetamine administration at very high doses.[150] The few studies that have used equivalent (weight-adjusted) human therapeutic doses and oral administration show that these changes, if they occur, are relatively minor.[150] This suggests that medical use of amphetamine does not significantly affect gene regulation.[150]

Pharmacological treatments

[edit]As of December 2019,[update] there is no effective pharmacotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[161][162][163] Reviews from 2015 and 2016 indicated that TAAR1-selective agonists have significant therapeutic potential as a treatment for psychostimulant addictions;[39][164] however, as of February 2016,[update] the only compounds which are known to function as TAAR1-selective agonists are experimental drugs.[39][164] Amphetamine addiction is largely mediated through increased activation of dopamine receptors and co-localized NMDA receptors[note 14] in the nucleus accumbens;[142] magnesium ions inhibit NMDA receptors by blocking the receptor calcium channel.[142][165] One review suggested that, based upon animal testing, pathological (addiction-inducing) psychostimulant use significantly reduces the level of intracellular magnesium throughout the brain.[142] Supplemental magnesium[note 15] treatment has been shown to reduce amphetamine self-administration (i.e., doses given to oneself) in humans, but it is not an effective monotherapy for amphetamine addiction.[142]

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2019 assessed the efficacy of 17 different pharmacotherapies used in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for amphetamine and methamphetamine addiction;[162] it found only low-strength evidence that methylphenidate might reduce amphetamine or methamphetamine self-administration.[162] There was low- to moderate-strength evidence of no benefit for most of the other medications used in RCTs, which included antidepressants (bupropion, mirtazapine, sertraline), antipsychotics (aripiprazole), anticonvulsants (topiramate, baclofen, gabapentin), naltrexone, varenicline, citicoline, ondansetron, prometa, riluzole, atomoxetine, dextroamphetamine, and modafinil.[162]

Behavioral treatments

[edit]A 2018 systematic review and network meta-analysis of 50 trials involving 12 different psychosocial interventions for amphetamine, methamphetamine, or cocaine addiction found that combination therapy with both contingency management and community reinforcement approach had the highest efficacy (i.e., abstinence rate) and acceptability (i.e., lowest dropout rate).[166] Other treatment modalities examined in the analysis included monotherapy with contingency management or community reinforcement approach, cognitive behavioral therapy, 12-step programs, non-contingent reward-based therapies, psychodynamic therapy, and other combination therapies involving these.[166]

Additionally, research on the neurobiological effects of physical exercise suggests that daily aerobic exercise, especially endurance exercise (e.g., marathon running), prevents the development of drug addiction and is an effective adjunct therapy (i.e., a supplemental treatment) for amphetamine addiction.[sources 10] Exercise leads to better treatment outcomes when used as an adjunct treatment, particularly for psychostimulant addictions.[146][148][167] In particular, aerobic exercise decreases psychostimulant self-administration, reduces the reinstatement (i.e., relapse) of drug-seeking, and induces increased dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) density in the striatum.[145][167] This is the opposite of pathological stimulant use, which induces decreased striatal DRD2 density.[145] One review noted that exercise may also prevent the development of a drug addiction by altering ΔFosB or c-Fos immunoreactivity in the striatum or other parts of the reward system.[147]

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity |

Type of reinforcer | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse | Physical exercise (aerobic) |

Environmental enrichment | ||

| ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type MSNs |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [145] |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | [145] | |||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization |

Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | [145] |

| Psychostimulant self-administration |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [145] | |

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [145] |

| Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [145] | ||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

| CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [145] | |

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens |

No | Yes | No | Yes | [145] | ||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [145] | |

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | [145] |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin |

↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [145] | |

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [145] | |||

| Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [145] | |||

Dependence and withdrawal

[edit]Drug tolerance develops rapidly in amphetamine abuse (i.e., recreational amphetamine use), so periods of extended abuse require increasingly larger doses of the drug in order to achieve the same effect.[168][169] According to a Cochrane review on withdrawal in individuals who compulsively use amphetamine and methamphetamine, "when chronic heavy users abruptly discontinue amphetamine use, many report a time-limited withdrawal syndrome that occurs within 24 hours of their last dose."[170] This review noted that withdrawal symptoms in chronic, high-dose users are frequent, occurring in roughly 88% of cases, and persist for 3–4 weeks with a marked "crash" phase occurring during the first week.[170] Amphetamine withdrawal symptoms can include anxiety, drug craving, depressed mood, fatigue, increased appetite, increased movement or decreased movement, lack of motivation, sleeplessness or sleepiness, and lucid dreams.[170] The review indicated that the severity of withdrawal symptoms is positively correlated with the age of the individual and the extent of their dependence.[170]

According to a 2025 review, the discontinuation of amphetamine at therapeutic doses does not typically result in withdrawal symptoms.[171] Discontinuation may unmask or cause a rebound of ADHD symptoms due to the cessation of treatment-related drug effects.[171] In cases where mild withdrawal symptoms do occur, they can be avoided by tapering the dose.[1] Unlike amphetamine abuse, where drug tolerance necessitates escalating doses to achieve the same effect, tolerance to clinically relevant doses of amphetamine plateaus after the initial titration period, and "drug holidays" (i.e., temporary treatment discontinuation) are not required to prevent the development of tolerance.[171]

Overdose

[edit]An amphetamine overdose can lead to many different symptoms, but is rarely fatal with appropriate care.[1][119][172] The severity of overdose symptoms increases with dosage and decreases with drug tolerance to amphetamine.[40][119] Tolerant individuals have been known to take as much as 5 grams of amphetamine in a day, which is roughly 100 times the maximum daily therapeutic dose.[119] Symptoms of a moderate and extremely large overdose are listed below; fatal amphetamine poisoning usually also involves convulsions and coma.[28][40] In 2013, overdose on amphetamine, methamphetamine, and other compounds implicated in an "amphetamine use disorder" resulted in an estimated 3,788 deaths worldwide (3,425–4,145 deaths, 95% confidence).[note 16][173]

| System | Minor or moderate overdose[28][40][119] | Severe overdose[sources 13] |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

| |

| Central nervous system |

|

|

| Musculoskeletal |

| |

| Respiratory |

|

|

| Urinary |

|

|

| Other |

|

|

Toxicity

[edit]In rodents and primates, sufficiently high doses of amphetamine cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity, or damage to dopamine neurons, which is characterized by dopamine terminal degeneration and reduced transporter and receptor function.[175][176] There is no evidence that amphetamine is directly neurotoxic in humans.[177][178] However, large doses of amphetamine may indirectly cause dopaminergic neurotoxicity as a result of hyperpyrexia, the excessive formation of reactive oxygen species, and increased autoxidation of dopamine.[sources 14] Animal models of neurotoxicity from high-dose amphetamine exposure indicate that the occurrence of hyperpyrexia (i.e., core body temperature ≥ 40 °C) is necessary for the development of amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity.[176] Prolonged elevations of brain temperature above 40 °C likely promote the development of amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in laboratory animals by facilitating the production of reactive oxygen species, disrupting cellular protein function, and transiently increasing blood–brain barrier permeability.[176]

Psychosis

[edit]An amphetamine overdose can result in a stimulant psychosis that may involve a variety of symptoms, such as delusions and paranoia.[41][42] A Cochrane review on treatment for amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methamphetamine psychosis states that about 5–15% of users fail to recover completely.[41][181] According to the same review, there is at least one trial that shows antipsychotic medications effectively resolve the symptoms of acute amphetamine psychosis.[41] Psychosis rarely arises from therapeutic use.[28][42][43]

Drug interactions

[edit]Many types of substances are known to interact with amphetamine, resulting in altered drug action or metabolism of amphetamine, the interacting substance, or both.[28] Inhibitors of enzymes that metabolize amphetamine (e.g., CYP2D6 and FMO3) will prolong its elimination half-life, meaning that its effects will last longer.[5][28] Amphetamine also interacts with MAOIs, particularly monoamine oxidase A inhibitors, since both MAOIs and amphetamine increase plasma catecholamines (i.e., norepinephrine and dopamine);[28] therefore, concurrent use of both is dangerous.[28] Amphetamine modulates the activity of most psychoactive drugs. In particular, amphetamine may decrease the effects of sedatives and depressants and increase the effects of stimulants and antidepressants.[28] Amphetamine may also decrease the effects of antihypertensives and antipsychotics due to its effects on blood pressure and dopamine respectively.[28] Zinc supplementation may reduce the minimum effective dose of amphetamine when it is used for the treatment of ADHD.[note 17][186] Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) like atomoxetine prevent norepinephrine release induced by amphetamines and have been found to reduce the stimulant, euphoriant, and sympathomimetic effects of dextroamphetamine in humans.[187][188][189]

In general, there is no significant interaction when consuming amphetamine with food, but the pH of gastrointestinal content and urine affects the absorption and excretion of amphetamine, respectively.[28] Acidic substances reduce the absorption of amphetamine and increase urinary excretion, and alkaline substances do the opposite.[28] Due to the effect pH has on absorption, amphetamine also interacts with gastric acid reducers such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 antihistamines, which increase gastrointestinal pH (i.e., make it less acidic).[28]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

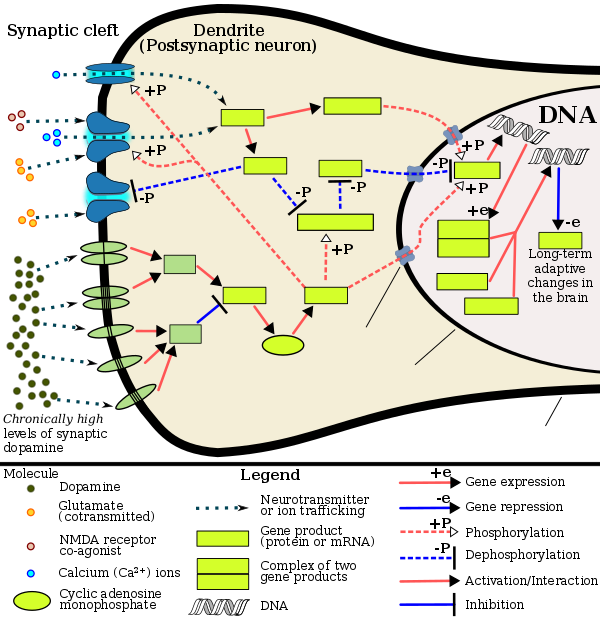

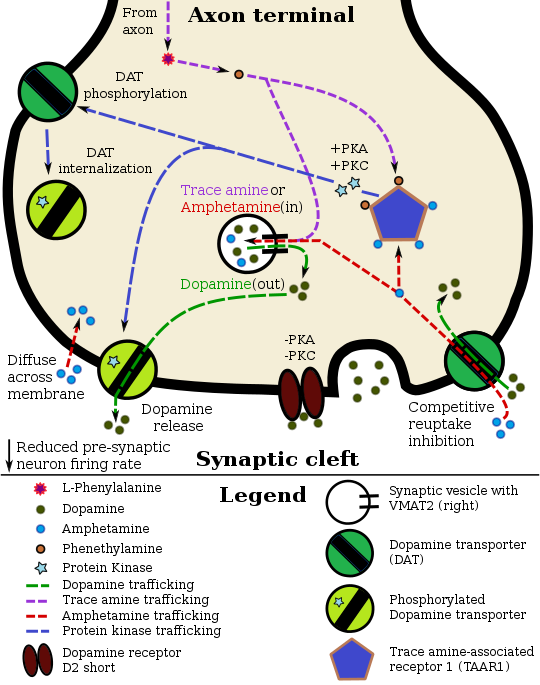

[edit]Pharmacodynamics of amphetamine in a dopamine neuron

|

Amphetamine exerts its behavioral effects by altering the use of monoamines as neuronal signals in the brain, primarily in catecholamine neurons in the reward and executive function pathways of the brain.[38][62] The concentrations of the main neurotransmitters involved in reward circuitry and executive functioning, dopamine and norepinephrine, increase dramatically in a dose-dependent manner by amphetamine because of its effects on monoamine transporters.[38][62][190] The reinforcing and motivational salience-promoting effects of amphetamine are due mostly to enhanced dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic pathway.[26] The euphoric and locomotor-stimulating effects of amphetamine are dependent upon the magnitude and speed by which it increases synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine concentrations in the striatum.[24]

Amphetamine potentiates monoaminergic neurotransmission primarily by entering axon terminals either through active transport by monoamine transporters (DAT, NET, and SERT) or by passive diffusion across neuronal membranes.[197][198] The uptake of amphetamine through these transporters competitively inhibits the reuptake of monoamine neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft, thereby elevating their synaptic concentrations.[197][199] Once inside the neuronal cytosol, amphetamine initiates intracellular signaling cascades involving protein kinases, including protein kinase C (PKC) and Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha (CaMKIIα), leading to the phosphorylation of specific monoamine transporters and modification of their activity.[198][199] PKC-mediated phosphorylation can either reverse transporter function to facilitate neurotransmitter efflux into the synaptic cleft or induce transporter internalization, resulting in non-competitive inhibition of neurotransmitter reuptake.[198][200] In contrast, CaMKIIα-mediated transporter phosphorylation selectively reverses DAT and NET to confer dopamine and norepinephrine efflux respectively, but unlike PKC does not terminate transporter function through internalization.[198][201]

Amphetamine has been identified as a full agonist of trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1), a Gs-coupled and G13-coupled G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) discovered in 2001, which is important for regulation of brain monoamines.[38][202] Several reviews have linked amphetamine's agonism at TAAR1 to modulation of monoamine transporter function and subsequent neurotransmitter efflux and reuptake inhibition at monoaminergic synapses.[sources 15] Activation of TAAR1 increases cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase activation, which triggers protein kinase A (PKA)- and PKC-mediated transporter phosphorylation.[38][78][205] Monoamine autoreceptors (e.g., D2 short, presynaptic α2, and presynaptic 5-HT1A) have the opposite effect of TAAR1, and together these receptors provide a regulatory system for monoamines.[38][39][202] Notably, amphetamine and trace amines possess high binding affinities for TAAR1, but not for monoamine autoreceptors.[38][39] Although TAAR1 is implicated in amphetamine-induced transporter phosphorylation, the magnitude of TAAR1-mediated monoamine release in humans remains unclear.[sources 15][202] Findings from studies using TAAR1 gene knockout models suggest that, despite facilitating reverse transport through Gs-coupled receptor-mediated cAMP signaling, TAAR1 may paradoxically attenuate amphetamine's psychostimulant effects by opening G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels through a Gs-independent pathway, an action that reduces neuronal firing.[206][38][202]

Amphetamine is also a substrate for the vesicular monoamine transporters VMAT1 and VMAT2.[192][207] Under normal conditions, VMAT2 transports cytosolic monoamines into synaptic vesicles for storage and later exocytotic release. When amphetamine accumulates in the presynaptic terminal, it collapses the vesicular pH gradient and releases vesicular monoamines into the neuronal cytosol.[192][207] These displaced monoamines expand the cytosolic pool available for reverse transport, thereby increasing the capacity for monoamine efflux beyond that achieved by amphetamine-mediated transporter phosphorylation alone.[199][201][207] Although VMAT2 is recognized as a major target in amphetamine-induced monoamine release at higher doses, some reviews have challenged its relevance at therapeutic doses.[197][207][208]

In addition to membrane and vesicular monoamine transporters, amphetamine also inhibits SLC1A1, SLC22A3, and SLC22A5.[sources 16] SLC1A1 is excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3), a glutamate transporter located in neurons, SLC22A3 is an extraneuronal monoamine transporter that is present in astrocytes, and SLC22A5 is a high-affinity carnitine transporter.[sources 16] Amphetamine is known to strongly induce cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) gene expression,[9][214] a neuropeptide involved in feeding behavior, stress, and reward, which induces observable increases in neuronal development and survival in vitro.[9][215][216] The CART receptor has yet to be identified, but there is significant evidence that CART binds to a unique Gi/Go-coupled GPCR.[216][217] Amphetamine also inhibits monoamine oxidases at very high doses, resulting in less monoamine and trace amine metabolism and consequently higher concentrations of synaptic monoamines.[208][21][218] In humans, the only post-synaptic receptor at which amphetamine is known to bind is the 5-HT1A receptor, where it acts as an agonist with low micromolar affinity.[219][220]

The full profile of amphetamine's short-term drug effects in humans is mostly derived through increased cellular communication or neurotransmission of dopamine,[38] serotonin,[38] norepinephrine,[38] epinephrine,[190] histamine,[190] CART peptides,[9][214] endogenous opioids,[221][222][223] adrenocorticotropic hormone,[224][225] corticosteroids,[224][225] and glutamate,[195][210] which it affects through interactions with CART, 5-HT1A, EAAT3, TAAR1, VMAT1, VMAT2, and possibly other biological targets.[sources 17] Amphetamine also activates seven human carbonic anhydrase enzymes, several of which are expressed in the human brain.[226]

Dextroamphetamine displays higher binding affinity for DAT than levoamphetamine, whereas both enantiomers share comparable affinity at NET;[197] Consequently, dextroamphetamine produces greater CNS stimulation than levoamphetamine, roughly three to four times more, but levoamphetamine has slightly stronger cardiovascular and peripheral effects.[197][40] Dextroamphetamine is also a more potent agonist of TAAR1 than levoamphetamine.[227][228]

Dopamine

[edit]In certain brain regions, amphetamine increases the concentration of dopamine in the synaptic cleft by modulating DAT through several overlapping processes.[201][198][78] Amphetamine can enter the presynaptic neuron either through DAT or, to a lesser extent, by diffusing across the neuronal membrane directly.[38][198] As a consequence of DAT uptake, amphetamine produces competitive reuptake inhibition at the transporter.[197][199] Upon entering the presynaptic neuron, amphetamine provokes the release of Ca²⁺ from endoplasmic reticulum stores, an effect that raises intracellular calcium to levels sufficient for downstream kinase-dependent signalling.[200][201] In parallel, amphetamine also increases intracellular cAMP, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC), whilst elevated intracellular Ca²⁺ activates PKC alone.[204][198][78] Phosphorylation of DAT by either kinase induces transporter internalization (non-competitive reuptake inhibition), but PKC-mediated phosphorylation alone induces the reversal of dopamine transport through DAT (i.e., dopamine efflux).[198][200]

TAAR1 has been identified as a biomolecular target of amphetamine that initiates some of amphetamine's kinase-dependent signaling cascades.[204][198][78] When TAAR1 signals via Gs-coupled receptors, intracellular cAMP increases through adenylyl cyclase activation and activates PKA and PKC, in turn phosphorylating DAT.[78][204] TAAR1 also couples G-protein alpha subunit G13;[229] when triggered by amphetamine, this pathway activates Ras homolog A (RhoA) and its downstream effector, Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase (ROCK), an effect that internalizes both DAT and the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAT3.[note 18][230][198] Transporter internalization via TAAR1's G13-coupled pathway is transient because Gs-cAMP-PKA signaling functionally inhibits RhoA's downstream activity;[229][231] once intracellular cAMP sufficiently accumulates, PKA is activated and phosphorylates RhoA, thereby terminating ROCK-mediated transporter internalization.[230][198] In addition to presynaptic actions that regulate DAT, TAAR1 activation exerts a somatodendritic inhibitory influence on dopamine output by reducing the firing rate of midbrain dopamine neurons via G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels, an effect that can attenuate amphetamine's psychostimulant response.[202][193][194]

Amphetamine's effect on intracellular calcium is associated with DAT phosphorylation through Ca²⁺/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II alpha (CAMKIIα), in turn producing dopamine efflux.[198][200][196] Because conventional PKC isoforms can be activated by Ca²⁺ and diacylglycerol, elevated intracellular calcium can promote PKC-dependent DAT phosphorylation independent of TAAR1.[201]

| Biological target of amphetamine | Initial effector / G-protein | Second messenger(s) | Secondary effector protein kinase |

Phosphorylated transporter | Effect on transporter function | Effect on neurotransmission | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unidentified | Unidentified intracellular effector | IP₃-mediated intracellular Ca²⁺ release | CAMKIIα | DAT | Reverse transport of dopamine | Dopamine efflux into synaptic cleft | [201][200] |

| TAAR1 | G13 | RhoA–GTP | ROCK† | DAT | Transporter internalization | Dopamine reuptake inhibition | [198][231][230] |

| TAAR1 | G13 | RhoA–GTP | ROCK† | EAAT3 | Transporter internalization | Glutamate reuptake inhibition | [198][202][230] |

| TAAR1 | Gs | ↑ cAMP | PKA | DAT | Transporter internalization | Dopamine reuptake inhibition | [38][198][78] |

| TAAR1 | Gs | ↑ cAMP | PKC | DAT | Reverse transport of dopamine Transporter internalization |

Dopamine efflux into synaptic cleft Dopamine reuptake inhibition |

[38][78][204] |

| Unidentified | Unidentified intracellular effector | IP₃/DAG pathway‡ | PKC | DAT | Reverse transport of dopamine Transporter internalization |

Dopamine efflux into synaptic cleft Dopamine reuptake inhibition |

[201][200] |

| †ROCK-mediated transporter internalization is transient due to the inactivation of RhoA (which activates ROCK) by PKA.

‡IP₃ binds to its receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum to release intracellular Ca²⁺ stores, and together with diacylglycerol activates conventional PKC isoforms. |

[198][200][230] | ||||||

Amphetamine is also a substrate for the presynaptic vesicular monoamine transporter, VMAT2.[192] Following amphetamine uptake at VMAT2, amphetamine induces the collapse of the vesicular pH gradient, which results in a dose-dependent release of dopamine molecules from synaptic vesicles into the cytosol via dopamine efflux through VMAT2.[192][207] Subsequently, the cytosolic dopamine molecules are released from the presynaptic neuron into the synaptic cleft via reverse transport at DAT.[199][192][207]

Norepinephrine

[edit]Similar to dopamine, amphetamine dose-dependently increases the level of synaptic norepinephrine, the direct precursor of epinephrine. Amphetamine is believed to affect norepinephrine analogously to dopamine.[198][201][78] In other words, amphetamine induces competitive NET reuptake inhibition, non-competitive reuptake inhibition and efflux at phosphorylated NET via PKC activation, CAMKIIα-mediated NET efflux without internalization, and norepinephrine release from VMAT2.[198][201][78]

Serotonin

[edit]Amphetamine exerts analogous, yet less pronounced, effects on serotonin as on dopamine and norepinephrine.[38] Amphetamine affects serotonin via VMAT2 and is thought to phosphorylate SERT via a PKC-dependent signaling cascade.[78] Like dopamine, amphetamine has low, micromolar affinity at the human 5-HT1A receptor.[219][220]

Other neurotransmitters, peptides, hormones, and enzymes

[edit]| Enzyme | KA (nM) | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| hCA4 | 94 | [226] |

| hCA5A | 810 | [226][232] |

| hCA5B | 2560 | [226] |

| hCA7 | 910 | [226][232] |

| hCA12 | 640 | [226] |

| hCA13 | 24100 | [226] |

| hCA14 | 9150 | [226] |

Acute amphetamine administration in humans increases endogenous opioid release in several brain structures in the reward system.[221][222][223] Extracellular levels of glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, have been shown to increase in the striatum following exposure to amphetamine.[195] This increase in extracellular glutamate presumably occurs via the amphetamine-induced internalization of EAAT3, a glutamate reuptake transporter, in dopamine neurons.[195][210] This internalization is mediated by RhoA activation and its downstream effector ROCK.[198][233] Amphetamine also induces the selective release of histamine from mast cells and efflux from histaminergic neurons through VMAT2.[190] Acute amphetamine administration can also increase adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosteroid levels in blood plasma by stimulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.[35][224][225]

In December 2017, the first study assessing the interaction between amphetamine and human carbonic anhydrase enzymes was published;[226] of the eleven carbonic anhydrase enzymes it examined, it found that amphetamine potently activates seven, four of which are highly expressed in the human brain, with low nanomolar through low micromolar activating effects.[226] Based upon preclinical research, cerebral carbonic anhydrase activation has cognition-enhancing effects;[234] but, based upon the clinical use of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, carbonic anhydrase activation in other tissues may be associated with adverse effects, such as ocular activation exacerbating glaucoma.[234]

Sex-dependent differences

[edit]Clinical research indicates that the pharmacological effects of amphetamine may vary depending on sex and menstrual cycle phase, possibly due to fluctuations in female sex hormones.[sources 18] In menstruating individuals, subjective and behavioral responses to amphetamine are heightened during the follicular phase (i.e., when estrogen levels are higher), and reduced during the luteal phase (i.e., when progesterone is elevated).[235][236][238] Reviews of human studies have also noted that men typically report stronger positive subjective responses to amphetamine compared to women tested during the luteal phase, whereas these sex differences are absent when women are tested during the follicular phase;[sources 18] subjective responses to amphetamine appear to correlate positively with plasma or salivary estrogen concentrations.[235][238] Moreover, neuroimaging studies have reported significant sex differences in the neural response to amphetamine in humans, including differences in dopamine release within the striatum and other brain regions.[239][240]

Preclinical studies have also produced findings of sex-dependent differences in drug response to amphetamine.[240][241] In contrast to human studies, adult female rats exhibit markedly greater dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens and more pronounced behavioral effects from amphetamine administration relative to males, effects that may be modulated by fluctuating estradiol levels across the estrous cycle or more broadly by adult gonadal hormones.[239][240][241]

Some evidence suggests that amphetamine interacts more strongly with female sex hormones than other psychostimulants such as methylphenidate, which may result in relatively greater variability in drug response across the menstrual cycle.[235][237] Although preliminary observational evidence suggests potential benefit from adjusting amphetamine doses according to menstrual cycle phases, randomized controlled trials have not evaluated this practice.[235][236][171]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The oral bioavailability of amphetamine varies with gastrointestinal pH;[28] it is well absorbed from the gut, and bioavailability is typically 90%.[8] Amphetamine is a weak base with a pKa of 9.9;[2] consequently, when the pH is basic, more of the drug is in its lipid soluble free base form, and more is absorbed through the lipid-rich cell membranes of the gut epithelium.[2][28] Conversely, an acidic pH means the drug is predominantly in a water-soluble cationic (salt) form, and less is absorbed.[2] Approximately 20% of amphetamine circulating in the bloodstream is bound to plasma proteins.[9] Following absorption, amphetamine readily distributes into most tissues in the body, with high concentrations occurring in cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[15]

The half-lives of amphetamine enantiomers differ and vary with urine pH.[2] At normal urine pH, the half-lives of dextroamphetamine and levoamphetamine are 9–11 hours and 11–14 hours, respectively.[2] Highly acidic urine will reduce the enantiomer half-lives to 7 hours;[15] highly alkaline urine will increase the half-lives up to 34 hours.[15] The immediate-release and extended release variants of salts of both isomers reach peak plasma concentrations at 3 hours and 7 hours post-dose respectively.[2] Amphetamine is eliminated via the kidneys, with 30–40% of the drug being excreted unchanged at normal urinary pH.[2] When the urinary pH is basic, amphetamine is in its free base form, so less is excreted.[2] When urine pH is abnormal, the urinary recovery of amphetamine may range from a low of 1% to a high of 75%, depending mostly upon whether urine is too basic or acidic, respectively.[2] Following oral administration, amphetamine appears in urine within 3 hours.[15] Roughly 90% of ingested amphetamine is eliminated 3 days after the last oral dose.[15]

Lisdexamfetamine is a prodrug of dextroamphetamine.[242][243] It is not as sensitive to pH as amphetamine when being absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract.[243] Following absorption into the blood stream, lisdexamfetamine is completely converted by red blood cells to dextroamphetamine and the amino acid L-lysine by hydrolysis via undetermined aminopeptidase enzymes.[243][242][244] This is the rate-limiting step in the bioactivation of lisdexamfetamine.[242] The elimination half-life of lisdexamfetamine is generally less than 1 hour.[243][242] Due to the necessary conversion of lisdexamfetamine into dextroamphetamine, levels of dextroamphetamine with lisdexamfetamine peak about one hour later than with an equivalent dose of immediate-release dextroamphetamine.[242][244] Presumably due to its rate-limited activation by red blood cells, intravenous administration of lisdexamfetamine shows greatly delayed time to peak and reduced peak levels compared to intravenous administration of an equivalent dose of dextroamphetamine.[242] The pharmacokinetics of lisdexamfetamine are similar regardless of whether it is administered orally, intranasally, or intravenously.[242][244] Hence, in contrast to dextroamphetamine, parenteral use does not enhance the subjective effects of lisdexamfetamine.[242][244] Because of its behavior as a prodrug and its pharmacokinetic differences, lisdexamfetamine has a longer duration of therapeutic effect than immediate-release dextroamphetamine and shows reduced misuse potential.[242][244]

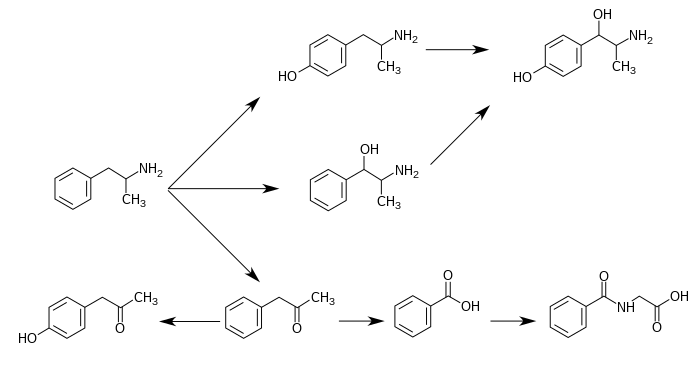

CYP2D6, dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3), butyrate-CoA ligase (XM-ligase), and glycine N-acyltransferase (GLYAT) are the enzymes known to metabolize amphetamine or its metabolites in humans.[sources 19] Amphetamine has a variety of excreted metabolic products, including 4-hydroxyamphetamine, 4-hydroxynorephedrine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetone, benzoic acid, hippuric acid, norephedrine, and phenylacetone.[2][10] Among these metabolites, the active sympathomimetics are 4-hydroxyamphetamine,[245] 4-hydroxynorephedrine,[246] and norephedrine.[247] The main metabolic pathways involve aromatic para-hydroxylation, aliphatic alpha- and beta-hydroxylation, N-oxidation, N-dealkylation, and deamination.[2][248] The known metabolic pathways, detectable metabolites, and metabolizing enzymes in humans include the following:

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 19]

|

Pharmacomicrobiomics

[edit]The human metagenome (i.e., the genetic composition of an individual and all microorganisms that reside on or within the individual's body) varies considerably between individuals.[254][255] Since the total number of microbial and viral cells in the human body (over 100 trillion) greatly outnumbers human cells (tens of trillions),[note 21][254][256] there is considerable potential for interactions between drugs and an individual's microbiome, including: drugs altering the composition of the human microbiome, drug metabolism by microbial enzymes modifying the drug's pharmacokinetic profile, and microbial drug metabolism affecting a drug's clinical efficacy and toxicity profile.[254][255][257] The field that studies these interactions is known as pharmacomicrobiomics.[254]

Similar to most biomolecules and other orally administered xenobiotics (i.e., drugs), amphetamine is predicted to undergo promiscuous metabolism by human gastrointestinal microbiota (primarily bacteria) prior to absorption into the blood stream.[257] The first amphetamine-metabolizing microbial enzyme, tyramine oxidase from a strain of E. coli commonly found in the human gut, was identified in 2019.[257] This enzyme was found to metabolize amphetamine, tyramine, and phenethylamine with roughly the same binding affinity for all three compounds.[257]

Related endogenous compounds

[edit]Amphetamine has a very similar structure and function to the endogenous trace amines, which are naturally occurring neuromodulator molecules produced in the human body and brain.[38][48][258] Among this group, the most closely related compounds are phenethylamine, the parent compound of amphetamine, and N-methylphenethylamine, a structural isomer of amphetamine (i.e., it has an identical molecular formula).[38][48][259] In humans, phenethylamine is produced directly from L-phenylalanine by the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) enzyme, which converts L-DOPA into dopamine as well.[48][259] In turn, N-methylphenethylamine is metabolized from phenethylamine by phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase, the same enzyme that metabolizes norepinephrine into epinephrine.[48][259] Like amphetamine, both phenethylamine and N-methylphenethylamine regulate monoamine neurotransmission via TAAR1;[38][258][259] unlike amphetamine, both of these substances are broken down by monoamine oxidase B, and therefore have a shorter half-life than amphetamine.[48][259]

Chemistry

[edit]Racemic amphetamine

|

Phenyl-2-nitropropene (right cups)

Amphetamine is a methyl homolog of the mammalian neurotransmitter phenethylamine with the chemical formula C9H13N. The carbon atom adjacent to the primary amine is a stereogenic center, and amphetamine is composed of a racemic 1:1 mixture of two enantiomers.[9] This racemic mixture can be separated into its optical isomers:[note 22] levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine.[9] At room temperature, the pure free base of amphetamine is a mobile, colorless, and volatile liquid with a characteristically strong amine odor, and acrid, burning taste.[20] Frequently prepared solid salts of amphetamine include amphetamine adipate,[260] aspartate,[28] hydrochloride,[261] phosphate,[262] saccharate,[28] sulfate,[28] and tannate.[263] Dextroamphetamine sulfate is the most common enantiopure salt.[49] Amphetamine is also the parent compound of its own structural class, which includes a number of psychoactive derivatives.[3][9] In organic chemistry, amphetamine is an excellent chiral ligand for the stereoselective synthesis of 1,1'-bi-2-naphthol.[264]

Substituted derivatives

[edit]The substituted derivatives of amphetamine, or "substituted amphetamines", are a broad range of chemicals that contain amphetamine as a "backbone";[3][50][265] specifically, this chemical class includes derivative compounds that are formed by replacing one or more hydrogen atoms in the amphetamine core structure with substituents.[3][50][266] The class includes amphetamine itself, stimulants like methamphetamine, serotonergic empathogens like MDMA, and decongestants like ephedrine, among other subgroups.[3][50][265]

Synthesis

[edit]Since the first preparation was reported in 1887,[267] numerous synthetic routes to amphetamine have been developed.[268][269] The most common route of both legal and illicit amphetamine synthesis employs a non-metal reduction known as the Leuckart reaction (method 1).[49][270] In the first step, a reaction between phenylacetone and formamide, either using additional formic acid or formamide itself as a reducing agent, yields N-formylamphetamine. This intermediate is then hydrolyzed using hydrochloric acid, and subsequently basified, extracted with organic solvent, concentrated, and distilled to yield the free base. The free base is then dissolved in an organic solvent, sulfuric acid added, and amphetamine precipitates out as the sulfate salt.[270][271]

A number of chiral resolutions have been developed to separate the two enantiomers of amphetamine.[268] For example, racemic amphetamine can be treated with d-tartaric acid to form a diastereoisomeric salt which is fractionally crystallized to yield dextroamphetamine.[272] Chiral resolution remains the most economical method for obtaining optically pure amphetamine on a large scale.[273] In addition, several enantioselective syntheses of amphetamine have been developed. In one example, optically pure (R)-1-phenyl-ethanamine is condensed with phenylacetone to yield a chiral Schiff base. In the key step, this intermediate is reduced by catalytic hydrogenation with a transfer of chirality to the carbon atom alpha to the amino group. Cleavage of the benzylic amine bond by hydrogenation yields optically pure dextroamphetamine.[273]

A large number of alternative synthetic routes to amphetamine have been developed based on classic organic reactions.[268][269] One example is the Friedel–Crafts alkylation of benzene by allyl chloride to yield beta chloropropylbenzene which is then reacted with ammonia to produce racemic amphetamine (method 2).[274] Another example employs the Ritter reaction (method 3). In this route, allylbenzene is reacted acetonitrile in sulfuric acid to yield an organosulfate which in turn is treated with sodium hydroxide to give amphetamine via an acetamide intermediate.[275][276] A third route starts with ethyl 3-oxobutanoate which through a double alkylation with methyl iodide followed by benzyl chloride can be converted into 2-methyl-3-phenyl-propanoic acid. This synthetic intermediate can be transformed into amphetamine using either a Hofmann or Curtius rearrangement (method 4).[277]

A significant number of amphetamine syntheses feature a reduction of a nitro, imine, oxime, or other nitrogen-containing functional groups.[269] In one such example, a Knoevenagel condensation of benzaldehyde with nitroethane yields phenyl-2-nitropropene. The double bond and nitro group of this intermediate is reduced using either catalytic hydrogenation or by treatment with lithium aluminium hydride (method 5).[270][278] Another method is the reaction of phenylacetone with ammonia, producing an imine intermediate that is reduced to the primary amine using hydrogen over a palladium catalyst or lithium aluminum hydride (method 6).[270]

|

|

|

Detection in body fluids

[edit]Amphetamine is frequently measured in urine or blood as part of a drug test for sports, employment, poisoning diagnostics, and forensics.[sources 20] Techniques such as immunoassay, which is the most common form of amphetamine test, may cross-react with a number of sympathomimetic drugs.[282] Chromatographic methods specific for amphetamine are employed to prevent false positive results.[283] Chiral separation techniques may be employed to help distinguish the source of the drug, whether prescription amphetamine, prescription amphetamine prodrugs, (e.g., selegiline), over-the-counter drug products that contain levomethamphetamine,[note 23] or illicitly obtained substituted amphetamines.[283][286][287] Several prescription drugs produce amphetamine as a metabolite, including benzphetamine, clobenzorex, famprofazone, fenproporex, lisdexamfetamine, mesocarb, methamphetamine, prenylamine, and selegiline, among others.[24][288][289] These compounds may produce positive results for amphetamine on drug tests.[288][289] Amphetamine is generally only detectable by a standard drug test for approximately 24 hours, although a high dose may be detectable for 2–4 days.[282]

For the assays, a study noted that an enzyme multiplied immunoassay technique (EMIT) assay for amphetamine and methamphetamine may produce more false positives than liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.[286] Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) of amphetamine and methamphetamine with the derivatizing agent (S)-(−)-trifluoroacetylprolyl chloride allows for the detection of methamphetamine in urine.[283] GC–MS of amphetamine and methamphetamine with the chiral derivatizing agent Mosher's acid chloride allows for the detection of both dextroamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine in urine.[283] Hence, the latter method may be used on samples that test positive using other methods to help distinguish between the various sources of the drug.[283]

History, society, and culture

[edit]| Substance | Best estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine- type stimulants |

34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| Cannabis | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| Cocaine | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| Ecstasy | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| Opiates | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| Opioids | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 in Germany by Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu who named it phenylisopropylamine;[267][291][292] its stimulant effects remained unknown until 1927, when it was independently resynthesized by Gordon Alles and reported to have sympathomimetic properties.[292] Amphetamine had no medical use until late 1933, when Smith, Kline and French began selling it as an inhaler under the brand name Benzedrine as a decongestant.[29] Benzedrine sulfate was introduced 3 years later and was used to treat a wide variety of medical conditions, including narcolepsy, obesity, low blood pressure, low libido, and chronic pain, among others.[51][29] During World War II, amphetamine and methamphetamine were used extensively by both the Allied and Axis forces for their stimulant and performance-enhancing effects.[267][293][294] As the addictive properties of the drug became known, governments began to place strict controls on the sale of amphetamine.[267] For example, during the early 1970s in the United States, amphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act.[7] In spite of strict government controls, amphetamine has been used legally or illicitly by people from a variety of backgrounds, including authors,[295] musicians,[296] mathematicians,[297] and athletes.[27]

Amphetamine is illegally synthesized in clandestine labs and sold on the black market, primarily in European countries.[298] Among European Union (EU) member states in 2018,[update] 11.9 million adults of ages 15–64 have used amphetamine or methamphetamine at least once in their lives and 1.7 million have used either in the last year.[299] During 2012, approximately 5.9 metric tons of illicit amphetamine were seized within EU member states;[300] the "street price" of illicit amphetamine within the EU ranged from €6–38 per gram during the same period.[300] Outside Europe, the illicit market for amphetamine is much smaller than the market for methamphetamine and MDMA.[298]

Legal status

[edit]As a result of the United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, amphetamine became a schedule II controlled substance, as defined in the treaty, in all 183 state parties.[30] Consequently, it is heavily regulated in most countries.[301][302] Some countries, such as South Korea and Japan, have banned substituted amphetamines even for medical use.[303][304] In other nations, such as Brazil (class A3),[305] Canada (schedule I drug),[306] the Netherlands (List I drug),[307] the United States (schedule II drug),[7] Australia (schedule 8),[308] Thailand (category 1 narcotic),[309] and United Kingdom (class B drug),[310] amphetamine is in a restrictive national drug schedule that allows for its use as a medical treatment.[298][31]

Pharmaceutical products

[edit]Several currently marketed amphetamine formulations contain both enantiomers, including those marketed under the brand names Adderall, Adderall XR, Mydayis,[note 1] Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo, and Evekeo ODT. Of those, Evekeo (including Evekeo ODT) is the only product containing only racemic amphetamine (as amphetamine sulfate), and is therefore the only one whose active moiety can be accurately referred to simply as "amphetamine".[1][35][123] Dextroamphetamine, marketed under the brand names Dexedrine and Zenzedi, is the only enantiopure amphetamine product currently available. A prodrug form of dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, is also available and is marketed under the brand name Vyvanse. As it is a prodrug, lisdexamfetamine is structurally different from dextroamphetamine, and is inactive until it metabolizes into dextroamphetamine.[37][243] The free base of racemic amphetamine was previously available as Benzedrine, Psychedrine, and Sympatedrine.[24] Levoamphetamine was previously available as Cydril.[24] Many current amphetamine pharmaceuticals are salts due to the comparatively high volatility of the free base.[24][37][49] However, oral suspension and orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) dosage forms composed of the free base were introduced in 2015 and 2016, respectively.[123][311][312] Some of the current brands and their generic equivalents are listed below.

| Brand name |

United States Adopted Name |

(D:L) ratio |

Dosage form |

Marketing start date |

Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adderall | – | 3:1 (salts) | tablet | 1996 | [24][37] |

| Adderall XR | – | 3:1 (salts) | capsule | 2001 | [24][37] |

| Mydayis | – | 3:1 (salts) | capsule | 2017 | [313][314] |

| Adzenys ER | amphetamine | 3:1 (base) | suspension | 2017 | [315] |

| Adzenys XR-ODT | amphetamine | 3:1 (base) | ODT | 2016 | [312][316] |

| Dyanavel XR | amphetamine | 3.2:1 (base) | suspension | 2015 | [123][311] |

| Evekeo | amphetamine sulfate | 1:1 (salts) | tablet | 2012 | [35][317] |

| Evekeo ODT | amphetamine sulfate | 1:1 (salts) | ODT | 2019 | [318] |

| Dexedrine | dextroamphetamine sulfate | 1:0 (salts) | capsule | 1976 | [24][37] |

| Zenzedi | dextroamphetamine sulfate | 1:0 (salts) | tablet | 2013 | [37][319] |

| Vyvanse | lisdexamfetamine dimesylate | 1:0 (prodrug) | capsule | 2007 | [24][243][320] |

| tablet | |||||

| Xelstrym | dextroamphetamine | 1:0 (base) | patch | 2022 | [321] |

| drug | formula | molar mass [note 24] |

amphetamine base [note 25] |

amphetamine base in equal doses |

doses with equal base content [note 26] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (g/mol) | (percent) | (30 mg dose) | ||||||||

| total | base | total | dextro- | levo- | dextro- | levo- | ||||

| dextroamphetamine sulfate[323][324] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

73.38%

|

—

|

22.0 mg

|

—

|

30.0 mg

| |

| amphetamine sulfate[325] | (C9H13N)2•H2SO4 | 368.49

|

270.41

|

73.38%

|

36.69%

|

36.69%

|

11.0 mg

|

11.0 mg