Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Water model

View on Wikipedia

In computational chemistry, a water model is used to simulate and thermodynamically calculate water clusters, liquid water, and aqueous solutions with explicit solvent, often using molecular dynamics or Monte Carlo methods. The models describe intermolecular forces between water molecules and are determined from quantum mechanics, molecular mechanics, experimental results, and these combinations. To imitate the specific nature of the intermolecular forces, many types of models have been developed. In general, these can be classified by the following three characteristics; (i) the number of interaction points or sites, (ii) whether the model is rigid or flexible, and (iii) whether the model includes polarization effects.

An alternative to the explicit water models is to use an implicit solvation model, also termed a continuum model. Examples of this type of model include the COSMO solvation model, the polarizable continuum model (PCM) and hybrid solvation models.[1]

Simple water models

[edit]The rigid models are considered the simplest water models and rely on non-bonded interactions. In these models, bonding interactions are implicitly treated by holonomic constraints. The electrostatic interaction is modeled using Coulomb's law, and the dispersion and repulsion forces using the Lennard-Jones potential.[2][3] The potential for models such as TIP3P (transferable intermolecular potential with 3 points) and TIP4P is represented by

where kC, the electrostatic constant, has a value of 332.1 Å·kcal/(mol·e²) in the units commonly used in molecular modeling[citation needed];[4][5][6] qi and qj are the partial charges relative to the charge of the electron; rij is the distance between two atoms or charged sites; and A and B are the Lennard-Jones parameters. The charged sites may be on the atoms or on dummy sites (such as lone pairs). In most water models, the Lennard-Jones term applies only to the interaction between the oxygen atoms.

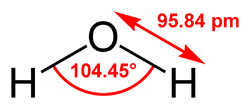

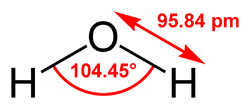

The figure below shows the general shape of the 3- to 6-site water models. The exact geometric parameters (the OH distance and the HOH angle) vary depending on the model.

2-site

[edit]A 2-site model of water based on the familiar three-site SPC model (see below) has been shown to predict the dielectric properties of water using site-renormalized molecular fluid theory.[7]

3-site

[edit]Three-site models have three interaction points corresponding to the three atoms of the water molecule. Each site has a point charge, and the site corresponding to the oxygen atom also has the Lennard-Jones parameters. Since 3-site models achieve a high computational efficiency, these are widely used for many applications of molecular dynamics simulations. Most of the models use a rigid geometry matching that of actual water molecules. An exception is the SPC model, which assumes an ideal tetrahedral shape (HOH angle of 109.47°) instead of the observed angle of 104.5°.

The table below lists the parameters for some 3-site models.

| TIPS[8] | SPC[9] | TIP3P[10] | SPC/E[11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(OH), Å | 0.9572 | 1.0 | 0.9572 | 1.0 |

| HOH, deg | 104.52 | 109.47 | 104.52 | 109.47 |

| A, 103 kcal Å12/mol | 580.0 | 629.4 | 582.0 | 629.4 |

| B, kcal Å6/mol | 525.0 | 625.5 | 595.0 | 625.5 |

| q(O) | −0.80 | −0.82 | −0.834 | −0.8476 |

| q(H) | +0.40 | +0.41 | +0.417 | +0.4238 |

The SPC/E model adds an average polarization correction to the potential energy function:

where μ is the electric dipole moment of the effectively polarized water molecule (2.35 D for the SPC/E model), μ0 is the dipole moment of an isolated water molecule (1.85 D from experiment), and αi is an isotropic polarizability constant, with a value of 1.608×10−40 F·m2. Since the charges in the model are constant, this correction just results in adding 1.25 kcal/mol (5.22 kJ/mol) to the total energy. The SPC/E model results in a better density and diffusion constant than the SPC model.

The TIP3P model implemented in the CHARMM force field is a slightly modified version of the original. The difference lies in the Lennard-Jones parameters: unlike TIP3P, the CHARMM version of the model places Lennard-Jones parameters on the hydrogen atoms too, in addition to the one on oxygen. The charges are not modified.[12] Three-site model (TIP3P) has better performance in calculating specific heats.[13]

Flexible SPC water model

[edit]

The flexible simple point-charge water model (or flexible SPC water model) is a re-parametrization of the three-site SPC water model.[14][15] The SPC model is rigid, whilst the flexible SPC model is flexible. In the model of Toukan and Rahman, the O–H stretching is made anharmonic, and thus the dynamical behavior is well described. This is one of the most accurate three-center water models without taking into account the polarization. In molecular dynamics simulations it gives the correct density and dielectric permittivity of water.[16]

Flexible SPC is implemented in the programs MDynaMix and Abalone.

Other models

[edit]4-site

[edit]The four-site models have four interaction points by adding one dummy atom near of the oxygen along the bisector of the HOH angle of the three-site models (labeled M in the figure). The dummy atom only has a negative charge. This model improves the electrostatic distribution around the water molecule. The first model to use this approach was the Bernal–Fowler model published in 1933,[21] which may also be the earliest water model. However, the BF model doesn't reproduce well the bulk properties of water, such as density and heat of vaporization, and is thus of historical interest only. This is a consequence of the parameterization method; newer models, developed after modern computers became available, were parameterized by running Metropolis Monte Carlo or molecular dynamics simulations and adjusting the parameters until the bulk properties are reproduced well enough.

The TIP4P model, first published in 1983, is widely implemented in computational chemistry software packages and often used for the simulation of biomolecular systems. There have been subsequent reparameterizations of the TIP4P model for specific uses: the TIP4P-Ew model, for use with Ewald summation methods; the TIP4P/Ice, for simulation of solid water ice; TIP4P/2005, a general parameterization for simulating the entire phase diagram of condensed water; and TIP4PQ/2005, a similar model but designed to accurately describe the properties of solid and liquid water when quantum effects are included in the simulation.[22]

Most of the four-site water models use an OH distance and HOH angle which match those of the free water molecule. One exception is the OPC model, in which no geometry constraints are imposed other than the fundamental C2v molecular symmetry of the water molecule. Instead, the point charges and their positions are optimized to best describe the electrostatics of the water molecule. OPC reproduces a comprehensive set of bulk properties more accurately than several of the commonly used rigid n-site water models. The OPC model is implemented within the AMBER force field.

| BF[21] | TIPS2[23] | TIP4P[10] | TIP4P-Ew[24] | TIP4P/Ice[25] | TIP4P/2005[26] | OPC[27] | TIP4P-D[28] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(OH), Å | 0.96 | 0.9572 | 0.9572 | 0.9572 | 0.9572 | 0.9572 | 0.8724 | 0.9572 |

| HOH, deg | 105.7 | 104.52 | 104.52 | 104.52 | 104.52 | 104.52 | 103.6 | 104.52 |

| r(OM), Å | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.125 | 0.1577 | 0.1546 | 0.1594 | 0.1546 |

| A, 103 kcal Å12/mol | 560.4 | 695.0 | 600.0 | 656.1 | 857.9 | 731.3 | 865.1 | 904.7 |

| B, kcal Å6/mol | 837.0 | 600.0 | 610.0 | 653.5 | 850.5 | 736.0 | 858.1 | 900.0 |

| q(M) | −0.98 | −1.07 | −1.04 | −1.04844 | −1.1794 | −1.1128 | −1.3582 | −1.16 |

| q(H) | +0.49 | +0.535 | +0.52 | +0.52422 | +0.5897 | +0.5564 | +0.6791 | +0.58 |

Others:

5-site

[edit]The 5-site models place the negative charge on dummy atoms (labelled L) representing the lone pairs of the oxygen atom, with a tetrahedral-like geometry. An early model of these types was the BNS model of Ben-Naim and Stillinger, proposed in 1971,[citation needed] soon succeeded by the ST2 model of Stillinger and Rahman in 1974.[31] Mainly due to their higher computational cost, five-site models were not developed much until 2000, when the TIP5P model of Mahoney and Jorgensen was published.[32] When compared with earlier models, the TIP5P model results in improvements in the geometry for the water dimer, a more "tetrahedral" water structure that better reproduces the experimental radial distribution functions from neutron diffraction, and the temperature of maximal density of water. The TIP5P-E model is a reparameterization of TIP5P for use with Ewald sums.

| BNS[31] | ST2[31] | TIP5P[32] | TIP5P-E[33] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r(OH), Å | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9572 | 0.9572 |

| HOH, deg | 109.47 | 109.47 | 104.52 | 104.52 |

| r(OL), Å | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| LOL, deg | 109.47 | 109.47 | 109.47 | 109.47 |

| A, 103 kcal Å12/mol | 77.4 | 238.7 | 544.5 | 554.3 |

| B, kcal Å6/mol | 153.8 | 268.9 | 590.3 | 628.2 |

| q(L) | −0.19562 | −0.2357 | −0.241 | −0.241 |

| q(H) | +0.19562 | +0.2357 | +0.241 | +0.241 |

| RL, Å | 2.0379 | 2.0160 | ||

| RU, Å | 3.1877 | 3.1287 |

Note, however, that the BNS and ST2 models do not use Coulomb's law directly for the electrostatic terms, but a modified version that is scaled down at short distances by multiplying it by the switching function S(r):

Thus, the RL and RU parameters only apply to BNS and ST2.

6-site

[edit]Originally designed to study water/ice systems, a 6-site model that combines all the sites of the 4- and 5-site models was developed by Nada and van der Eerden.[34] Since it had a very high melting temperature[35] when employed under periodic electrostatic conditions (Ewald summation), a modified version was published later[36] optimized by using the Ewald method for estimating the Coulomb interaction.

Other

[edit]- The effect of explicit solute model on solute behavior in biomolecular simulations has been also extensively studied. It was shown that explicit water models affected the specific solvation and dynamics of unfolded peptides, while the conformational behavior and flexibility of folded peptides remained intact.[37]

- MB model. A more abstract model resembling the Mercedes-Benz logo that reproduces some features of water in two-dimensional systems. It is not used as such for simulations of "real" (i.e., three-dimensional) systems, but it is useful for qualitative studies and for educational purposes.[38]

- Coarse-grained models. One- and two-site models of water have also been developed.[39] In coarse-grain models, each site can represent several water molecules.

- Many-body models. Water models built using training-set configurations solved quantum mechanically, which then use machine learning protocols to extract potential-energy surfaces. These potential-energy surfaces are fed into MD simulations for an unprecedented degree of accuracy in computing physical properties of condensed phase systems.[40]

Computational cost

[edit]The computational cost of a water simulation increases with the number of interaction sites in the water model. The CPU time is approximately proportional to the number of interatomic distances that need to be computed. For the 3-site model, 9 distances are required for each pair of water molecules (every atom of one molecule against every atom of the other molecule, or 3 × 3). For the 4-site model, 10 distances are required (every charged site with every charged site, plus the O–O interaction, or 3 × 3 + 1). For the 5-site model, 17 distances are required (4 × 4 + 1). Finally, for the 6-site model, 26 distances are required (5 × 5 + 1).

When using rigid water models in molecular dynamics, there is an additional cost associated with keeping the structure constrained, using constraint algorithms (although with bond lengths constrained it is often possible to increase the time step).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Skyner RE, McDonagh JL, Groom CR, van Mourik T, Mitchell JB (March 2015). "A review of methods for the calculation of solution free energies and the modelling of systems in solution" (PDF). Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 17 (9): 6174–91. Bibcode:2015PCCP...17.6174S. doi:10.1039/C5CP00288E. PMID 25660403.

- ^ Allen MP, Tildesley DJ (1989). Computer Simulation of Liquids. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-855645-9.

- ^ Kirby BJ. Micro- and Nanoscale Fluid Mechanics: Transport in Microfluidic Devices. Archived from the original on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Swails JM, Roitberg AE (2013). "prmtop file of {A}mber" (PDF).

- ^ Swails JM (2013). Free energy simulations of complex biological systems at constant pH (PDF). University of Florida. Bibcode:2013PhDT.......588S.

- ^ Case DA, Walker RC, Cheatham III TE, Simmerling CL, Roitberg A, Merz KM, et al. (April 2019). "Amber 2019 reference manual (covers Amber18 and AmberTools19)" (PDF).

- ^ Dyer KM, Perkyns JS, Stell G, Pettitt BM (2009). "Site-renormalised molecular fluid theory: on the utility of a two-site model of water". Molecular Physics. 107 (4–6): 423–431. Bibcode:2009MolPh.107..423D. doi:10.1080/00268970902845313. PMC 2777734. PMID 19920881.

- ^ Jorgensen, William L. (1981). "Quantum and statistical mechanical studies of liquids. 10. Transferable intermolecular potential functions for water, alcohols, and ethers. Application to liquid water". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 103 (2). American Chemical Society (ACS): 335–340. Bibcode:1981JAChS.103..335J. doi:10.1021/ja00392a016. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ H. J. C. Berendsen, J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, and J. Hermans, In Intermolecular Forces, edited by B. Pullman (Reidel, Dordrecht, 1981), p. 331.

- ^ a b Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML (1983). "Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 79 (2): 926–935. Bibcode:1983JChPh..79..926J. doi:10.1063/1.445869.

- ^ Berendsen HJ, Grigera JR, Straatsma TP (1987). "The missing term in effective pair potentials". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 91 (24): 6269–6271. doi:10.1021/j100308a038.

- ^ MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, et al. (April 1998). "All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 102 (18): 3586–616. doi:10.1021/jp973084f. PMID 24889800.

- ^ Mao Y, Zhang Y (2012). "Thermal conductivity, shear viscosity and specific heat of rigid water models". Chemical Physics Letters. 542: 37–41. Bibcode:2012CPL...542...37M. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2012.05.044.

- ^ Toukan K, Rahman A (March 1985). "Molecular-dynamics study of atomic motions in water". Physical Review B. 31 (5): 2643–2648. Bibcode:1985PhRvB..31.2643T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.31.2643. PMID 9936106.

- ^ Berendsen HJ, Grigera JR, Straatsma TP (1987). "The missing term in effective pair potentials". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 91 (24): 6269–6271. doi:10.1021/j100308a038.

- ^ Praprotnik M, Janezic D, Mavri J (2004). "Temperature Dependence of Water Vibrational Spectrum: A Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 108 (50): 11056–11062. Bibcode:2004JPCA..10811056P. doi:10.1021/jp046158d.

- ^ Ferguson, David M. (April 1995). "Parameterization and evaluation of a flexible water model". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 16 (4): 501–511. doi:10.1002/jcc.540160413. S2CID 206038409. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ MG model Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Kumagai N, Kawamura K, Yokokawa T (1994). "An Interatomic Potential Model for H2O: Applications to Water and Ice Polymorphs". Molecular Simulation. 12 (3–6). Informa UK Limited: 177–186. doi:10.1080/08927029408023028. ISSN 0892-7022.

- ^ Burnham CJ, Li J, Xantheas SS, Leslie M (1999). "The parametrization of a Thole-type all-atom polarizable water model from first principles and its application to the study of water clusters (n=2–21) and the phonon spectrum of ice Ih". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 110 (9): 4566–4581. Bibcode:1999JChPh.110.4566B. doi:10.1063/1.478797.

- ^ a b Bernal JD, Fowler RH (1933). "A Theory of Water and Ionic Solution, with Particular Reference to Hydrogen and Hydroxyl Ions". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1 (8): 515. Bibcode:1933JChPh...1..515B. doi:10.1063/1.1749327.

- ^ McBride, C.; Vega, C.; Noya, E.G.; Ramirez, R.; Sese', L.M. (2009). "Quantum contributions in the ice phases: The path to a new empirical model for water—TIP4PQ/2005". J. Chem. Phys. 131 (2): 024506. arXiv:0906.3967. Bibcode:2009JChPh.131b4506M. doi:10.1063/1.3175694. PMID 19604003. S2CID 15505037.

- ^ Jorgensen (1982). "Revised TIPS for simulations of liquid water and aqueous solutions". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 77 (8): 4156–4163. Bibcode:1982JChPh..77.4156J. doi:10.1063/1.444325.

- ^ Horn HW, Swope WC, Pitera JW, Madura JD, Dick TJ, Hura GL, Head-Gordon T (May 2004). "Development of an improved four-site water model for biomolecular simulations: TIP4P-Ew". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 120 (20): 9665–78. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.9665H. doi:10.1063/1.1683075. PMID 15267980. S2CID 39545298.

- ^ Abascal JL, Sanz E, García Fernández R, Vega C (June 2005). "A potential model for the study of ices and amorphous water: TIP4P/Ice". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 122 (23): 234511. Bibcode:2005JChPh.122w4511A. doi:10.1063/1.1931662. PMID 16008466. S2CID 8382245.

- ^ Abascal JL, Vega C (December 2005). "A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 123 (23): 234505. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123w4505A. doi:10.1063/1.2121687. PMID 16392929. S2CID 9757894.

- ^ Izadi S, Anandakrishnan R, Onufriev AV (November 2014). "Building Water Models: A Different Approach". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 5 (21): 3863–3871. arXiv:1408.1679. Bibcode:2014arXiv1408.1679I. doi:10.1021/jz501780a. PMC 4226301. PMID 25400877.

- ^ Piana S, Donchev AG, Robustelli P, Shaw DE (April 2015). "Water dispersion interactions strongly influence simulated structural properties of disordered protein states". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 119 (16): 5113–23. doi:10.1021/jp508971m. PMID 25764013.

- ^ Habershon, S.; Markland, T.E.; Manolopoulos, D.E. (2009). "Competing quantum effects in the dynamics of a flexible water model". J. Chem. Phys. 131 (2): 024501. arXiv:1011.1047. Bibcode:2009JChPh.131b4501H. doi:10.1063/1.3167790. PMID 19603998. S2CID 9095938.

- ^ Gonzalez, M.A.; Abascal, J.J.F. (2011). "A flexible model for water based on TIP4P/2005". J. Chem. Phys. 135 (22): 224516. Bibcode:2011JChPh.135v4516G. doi:10.1063/1.3663219. PMID 22168712.

- ^ a b c Stillinger FH, Rahman A (1974). "Improved simulation of liquid water by molecular dynamics". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 60 (4): 1545–1557. Bibcode:1974JChPh..60.1545S. doi:10.1063/1.1681229. S2CID 96035805.

- ^ a b Mahoney MW, Jorgensen WL (2000). "A five-site model for liquid water and the reproduction of the density anomaly by rigid, nonpolarizable potential functions". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 112 (20): 8910–8922. Bibcode:2000JChPh.112.8910M. doi:10.1063/1.481505. S2CID 16367148.

- ^ Rick SW (April 2004). "A reoptimization of the five-site water potential (TIP5P) for use with Ewald sums". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 120 (13): 6085–93. Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.6085R. doi:10.1063/1.1652434. PMID 15267492.

- ^ Nada, H. (2003). "An intermolecular potential model for the simulation of ice and water near the melting point: A six-site model of H2O". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 118 (16): 7401. Bibcode:2003JChPh.118.7401N. doi:10.1063/1.1562610.

- ^ Abascal JL, Fernández RG, Vega C, Carignano MA (October 2006). "The melting temperature of the six site potential model of water". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 125 (16): 166101. Bibcode:2006JChPh.125p6101A. doi:10.1063/1.2360276. PMID 17092145. S2CID 33883071.

- ^ Nada H (December 2016). "2O and a molecular dynamics simulation". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 145 (24): 244706. Bibcode:2016JChPh.145x4706N. doi:10.1063/1.4973000. PMID 28049310.

- ^ Florová P, Sklenovský P, Banáš P, Otyepka M (November 2010). "Explicit Water Models Affect the Specific Solvation and Dynamics of Unfolded Peptides While the Conformational Behavior and Flexibility of Folded Peptides Remain Intact". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 6 (11): 3569–79. doi:10.1021/ct1003687. PMID 26617103.

- ^ Silverstein KA, Haymet AD, Dill KA (1998). "A Simple Model of Water and the Hydrophobic Effect". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 120 (13): 3166–3175. Bibcode:1998JAChS.120.3166S. doi:10.1021/ja973029k.

- ^ Izvekov S, Voth GA (October 2005). "Multiscale coarse graining of liquid-state systems". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 123 (13). AIP Publishing: 134105. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123m4105I. doi:10.1063/1.2038787. PMID 16223273.

- ^ Medders GR, Paesani F (March 2015). "Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy of Liquid Water through "First-Principles" Many-Body Molecular Dynamics". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 11 (3): 1145–54. doi:10.1021/ct501131j. PMID 26579763.

- ^ Cisneros GA, Wikfeldt KT, Ojamäe L, Lu J, Xu Y, Torabifard H, et al. (July 2016). "Modeling Molecular Interactions in Water: From Pairwise to Many-Body Potential Energy Functions". Chemical Reviews. 116 (13): 7501–28. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00644. PMC 5450669. PMID 27186804.

- ^ Wikfeldt KT, Batista ER, Vila FD, Jónsson H (October 2013). "A transferable H2O interaction potential based on a single center multipole expansion: SCME". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 15 (39): 16542–56. arXiv:1306.0327. Bibcode:2013PCCP...1516542W. doi:10.1039/c3cp52097h. PMID 23949215. S2CID 15215071.

Water model

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and scope

Water models are simplified mathematical representations of the H₂O molecule employed in computational chemistry to approximate its intermolecular potential energy surface. These models use empirical parameters, such as partial atomic charges and van der Waals coefficients, which are derived from quantum mechanical calculations, experimental measurements, and optimization against bulk properties including density, radial distribution functions, and dielectric constant.[3][5][1] The scope of water models encompasses simulations of liquid water, ice phases, small clusters, and aqueous solutions containing solutes like ions or biomolecules, primarily through molecular dynamics and Monte Carlo methods. Key components include electrostatic interactions modeled via Coulombic potentials between charged sites on the molecules and van der Waals attractions/repulsions captured by Lennard-Jones potentials. Non-bonded interactions, which dominate intermolecular forces in these models, exclude covalent bonds within the water molecule itself and focus on long-range electrostatic and dispersion effects between separate molecules. The general form of the pairwise potential energy is: where and are partial charges on interaction sites and , is the inter-site distance, is the vacuum permittivity, and and are Lennard-Jones energy and size parameters, respectively.[1][6] Water models facilitate large-scale classical simulations of complex aqueous systems where ab initio quantum mechanical approaches are computationally prohibitive due to the need to treat thousands of molecules over extended timescales. This enables detailed studies of solvation dynamics, hydrogen bonding networks, and thermodynamic properties that underpin biological and chemical processes in water. In contrast to continuum solvation models, which approximate the solvent as a homogeneous dielectric continuum without explicit molecules, water models treat water as discrete particles to capture molecular-level details. The first computational use of such a model dates to the 1971 molecular dynamics simulation of liquid water by Rahman and Stillinger.[3][5][6]Historical development

The development of water models began in the early 20th century with theoretical efforts to describe the structure of ice and liquid water based on geometric considerations. In 1933, Bernal and Fowler proposed the first explicit model for water, representing the molecule as a rigid tetrahedron with two hydrogen atoms and a lone pair, emphasizing hydrogen bonding in ice structures without computational simulations.[7] This geometric approach laid foundational insights into water's anomalous properties but lacked dynamic treatment due to the absence of computing resources. The advent of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the 1970s marked a pivotal shift toward computational modeling of liquid water. The first MD simulation of liquid water was performed by Rahman and Stillinger in 1971, using a three-site potential to study structural and dynamic properties at ambient conditions, demonstrating the feasibility of simulating water's hydrogen-bond network. By 1974, Stillinger and Rahman refined this with the ST2 model, a six-site rigid water potential incorporating Lennard-Jones interactions and electrostatic charges to better capture short-range repulsion and hydrogen bonding, enabling more accurate reproduction of liquid water's radial distribution functions. Concurrently, the MCY potential, derived from ab initio configuration interaction calculations on water dimers—a pairwise additive model—addressed limitations in transferability across phases. These early efforts were motivated by the need to balance quantum-derived accuracy with the computational demands of MD, though models often overestimated melting points or struggled with dielectric properties. The 1980s saw simplifications for broader applicability, particularly in biomolecular simulations where efficiency was paramount. Jorgensen et al. introduced the three-site TIP3P and four-site TIP4P models in 1983, using fixed partial charges and Lennard-Jones sites to approximate water's electrostatics and dispersion with fewer parameters than ST2, facilitating Monte Carlo and MD studies of aqueous solutions.[8] In 1987, Berendsen et al. developed the SPC/E model, an extension of the earlier SPC three-site potential, by adding a polarization correction via a scaling factor to improve the dielectric constant and radial distribution at liquid densities. These rigid, non-polarizable models prioritized computational speed over detailed many-body effects, responding to challenges in simulating large systems like proteins in water. From the 1990s onward, models evolved to incorporate polarizability and optimize phase behavior. Polarizable models, such as the Gaussian charge transferable model in the 1990s, allowed charges to fluctuate in response to electric fields, enhancing accuracy for interfaces and ionic solutions. Further ab initio-based refinements continued, while the 2000s introduced AMOEBA, a polarizable atomic multipole model that explicitly includes higher-order electrostatics for better thermodynamic properties across temperatures. Optimized rigid models emerged, including TIP4P/2005 in 2005, which improved reproduction of water's phase diagram and anomalies like density maximum, and OPC in 2014, focusing on global optimization of bulk properties using experimental targets. Throughout, motivations centered on reconciling accuracy in reproducing experimental observables—such as the phase diagram, diffusion coefficients, and dielectric response—with computational efficiency, while addressing transferability issues across vapor, liquid, and solid phases. Post-2020, machine learning-based potentials, trained on quantum mechanical data, have begun to enable highly accurate, flexible representations of water's potential energy surface for large-scale simulations.Classification

By interaction sites

Water models are classified by the number of interaction sites, which are points representing partial charges and van der Waals interactions within the water molecule, including atomic positions (oxygen and hydrogens) or virtual (dummy) sites for lone pairs. These sites enable the modeling of electrostatic forces via Coulombic interactions between partial charges and Lennard-Jones potentials for dispersion and repulsion. Increasing the number of sites enhances the accuracy of the electrostatic charge distribution, better capturing the molecular dipole moment and hydrogen bonding geometry, but at the computational expense of more pairwise interactions per molecule pair.[9][10] Two-site models represent the simplest configuration, with partial charges placed only on the oxygen and a single effective site for the merged hydrogens, omitting explicit hydrogen positions to minimize complexity. This approach is particularly suited for applications requiring efficient predictions of dielectric properties, such as in coarse-grained simulations of bulk water behavior.[11] Three-site models assign partial charges directly to the oxygen and two hydrogen atoms, maintaining a rigid geometry that approximates the experimental structure, for example, with O-H bond lengths of 0.9572 Å and H-O-H angles of 104.52°. This setup balances computational efficiency with reasonable electrostatic representation, making it widely applicable for simulating liquid water properties.[9] Four-site models extend the three-site framework by introducing an off-center virtual negative charge site (M-site) along the angle bisector, typically displaced 0.15 Å from the oxygen, to improve the dipole moment and hydrogen bonding directionality without altering atomic positions. This addition refines the electrostatics for better agreement with experimental solvation and structural data.[9] Five-site models incorporate two positive charges on the hydrogens and two negative charges on virtual sites mimicking the tetrahedral lone pairs, with no charge on the oxygen atom, enhancing the tetrahedral coordination and density anomaly reproduction in liquid water.[12] Six-site models combine elements of four- and five-site designs, adding extra virtual sites to further detail charge distribution, though they are less common and primarily used for specialized simulations of ice-water interfaces near the melting point.[13] Overall, three- and four-site models predominate due to their optimal trade-off between accuracy and computational cost; the number of sites directly influences the pairwise interaction count, such as nine site-site distances for a three-site model pair versus more for higher-site variants.[9][10]By molecular flexibility and polarizability

Water models can be classified according to their treatment of molecular flexibility and polarizability, which extend beyond the static geometry and fixed charges of rigid, non-polarizable representations to better capture the dynamic behavior of water molecules in condensed phases.[14] Flexibility refers to the ability of the model to account for intramolecular vibrations, such as oscillations in bond lengths and angles, which are absent in rigid models that enforce fixed geometries using constraint algorithms like SHAKE. In flexible models, these degrees of freedom are governed by intramolecular potential energy functions, typically harmonic forms for stretching and bending: where and are the respective force constants, and and are the equilibrium bond length and angle. This approach enables the simulation of vibrational modes, improving the representation of dynamic properties like diffusion and spectroscopic signatures compared to constrained rigid baselines. Flexible models, such as variants of the simple point charge (SPC) potential developed in the 1990s, allow bond lengths to vary around experimental gas-phase values, enhancing realism in liquid-state simulations. Polarizability addresses the redistribution of a molecule's electron density in response to the local electric field from neighboring molecules, an effect ignored in fixed-charge models that assume invariant partial charges. In polarizable models, this induction is incorporated either implicitly or explicitly. Implicit schemes approximate the average polarization in bulk water by adjusting fixed charges to an effective value that mimics the enhanced molecular dipole moment, as in the SPC/E model where the charge is set to -0.8476 e on oxygen and +0.4238 e on each hydrogen to account for liquid-phase polarization without dynamic response. Explicit methods, however, directly compute the response, often via inducible point dipoles satisfying with the molecular polarizability , matching the experimental gas-phase value of water. One prevalent explicit approach uses Drude oscillators, where a lightweight negative charge is harmonically bound to an atomic site to represent electron cloud displacement under the field, enabling iterative or extended Lagrangian propagation in simulations.[15] Seminal explicit polarizable models include AMOEBA, introduced in 2003, which combines atomic multipoles with inducible dipoles for accurate many-body electrostatics. Incorporating flexibility and polarizability enhances the fidelity of simulations for properties sensitive to molecular dynamics, such as infrared (IR) spectra, where flexible models better reproduce experimental vibrational frequencies and widths by allowing explicit OH stretching and HOH bending modes. These advanced models also improve hydrogen bonding networks and dielectric responses in heterogeneous environments. However, they incur a computational overhead of 2-10 times compared to rigid non-polarizable counterparts due to additional degrees of freedom and field iterations, limiting their use to refined or smaller-scale studies despite the gains in accuracy.[16][17]Rigid non-polarizable models

Two-site models

Two-site models are the simplest rigid non-polarizable representations of water molecules in molecular simulations, consisting of two interaction sites: the oxygen atom and a single positive charge site that effectively merges the two hydrogen atoms along the molecular symmetry axis. This formulation simplifies the electrostatic interactions to a point-charge model, with the oxygen site assigned a negative charge (q_O) and the hydrogen site an equal-magnitude positive charge (q_H = -q_O) to maintain molecular neutrality. The Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential is restricted to oxygen-oxygen interactions to capture short-range dispersion and repulsion, while electrostatics dominate intersite forces involving the hydrogen site. Such models are particularly suited for theoretical analyses using integral equation methods, where the reduced number of sites facilitates analytical tractability.[18] The intermolecular pair potential in these models is expressed as where is the vector between molecular centers of mass, and denote molecular orientations, and is the distance between sites and on different molecules. The site-site potential combines Coulombic electrostatics, , for all pairs, with an additional LJ term only for O-O interactions: . Representative parameters, derived to approximate experimental properties like the gas-phase dipole moment of approximately 1.85 D, include kcal/mol, Å, and charges on the order of e (with site separation adjusted accordingly, e.g., around 0.7–1.0 Å along the bisector). These values stem from early basic formulations in the 1970s, refined in later theoretical works to balance simplicity and fidelity to bulk properties.[18] A seminal example is the two-site model proposed in 2009 for theoretical studies using integral equation methods, derived from the SPC model. This approach places the negative charge at the oxygen position and the positive charge at a displaced site to mimic the dipole, with no intramolecular flexibility or polarizability. The model's low computational cost arises from the minimal number of interactions (only four per pair: O-O LJ + Coulomb, O-H Coulomb twice, H-H Coulomb), making it ideal for large-scale simulations or analytical derivations in gas-phase studies and dielectric response calculations. For instance, site-renormalized molecular fluid theory using this model accurately predicts the static dielectric constant of liquid water near 300 K (ε ≈ 78) by treating sites as effective simple fluids.[18] Despite these advantages, two-site models exhibit significant limitations in reproducing the structural properties of liquid water, such as radial distribution functions and hydrogen bonding networks, due to the absence of explicit angular dependence from separate hydrogen sites. Simulations often overestimate liquid density by 10–20% at ambient conditions and fail to capture tetrahedral coordination, leading to unrealistic diffusion coefficients and solvation free energies for polar solutes. Consequently, these models are rarely employed standalone for condensed-phase simulations today, serving instead as baselines for comparison with more elaborate three- or four-site variants or in preliminary theoretical explorations.[18]Three-site models

Three-site models represent a class of rigid, non-polarizable water potentials that place partial charges on the oxygen atom and the two hydrogen atoms, enabling explicit representation of hydrogen bonding interactions. These models typically employ a fixed geometry derived from experimental gas-phase values, with bond lengths of OH = 0.9572 Å and the HOH angle = 104.52°, while the Lennard-Jones (LJ) interaction is centered solely on the oxygen site. The partial charges generally range from q_O = -0.8 to -1.04 e and q_H = +0.4 to +0.52 e, balancing the molecular dipole moment (approximately 1.85 D) and electrostatic interactions. Among the earliest three-site models is the Transferable Intermolecular Potential with Superimposed charges (TIPS), introduced as a precursor to later variants, which uses charges of q_O = -0.80 e and q_H = +0.40 e, along with LJ parameters ε = 0.15 kcal/mol and σ = 3.12 Å to approximate liquid properties in Monte Carlo simulations. The Simple Point Charge (SPC) model, developed in 1981, refines this approach with q_O = -0.82 e, q_H = +0.41 e, ε = 0.110 kcal/mol, and σ = 3.166 Å, prioritizing computational efficiency for molecular dynamics (MD) studies of protein hydration. Concurrently, the Transferable Intermolecular Potential 3-Point (TIP3P) model from 1983 employs slightly adjusted parameters: q_O = -0.834 e, q_H = +0.417 e, ε = 0.152 kcal/mol, and σ = 3.1507 Å, offering improved reproduction of vapor pressure and solvation free energies compared to SPC. To address limitations in dielectric screening, the SPC/E (extended SPC) model was proposed in 1987, scaling the charges to q_O = -0.8476 e and q_H = +0.4238 e while retaining the original LJ parameters and geometry; this adjustment mimics average polarization effects without explicit polarizability, enhancing agreement with experimental radial distribution functions. These models evolved from two-site representations by incorporating explicit hydrogen sites, which better capture directional hydrogen bonding essential for biomolecular environments.| Model | Year | q_O (e) | q_H (e) | ε (kcal/mol) | σ (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIPS | 1981 | -0.80 | +0.40 | 0.15 | 3.12 |

| SPC | 1981 | -0.82 | +0.41 | 0.110 | 3.166 |

| TIP3P | 1983 | -0.834 | +0.417 | 0.152 | 3.1507 |

| SPC/E | 1987 | -0.8476 | +0.4238 | 0.110 | 3.166 |

Four-site models

Four-site water models extend the three-site rigid non-polarizable framework by introducing a fourth massless site (M) bearing a negative charge, positioned along the bisector of the H-O-H angle and displaced from the oxygen atom by 0.15–0.18 Å. This configuration places zero charge on the oxygen (q_O ≈ 0 e), positive charges on the hydrogens (q_H ≈ +0.52 e), and a balancing negative charge on the M site (q_M ≈ -1.04 e), with Lennard-Jones interactions assigned solely to the oxygen site. The electrostatic interactions are modeled using Coulombic potentials between all charged sites, yielding an effective molecular dipole moment of approximately 2.18 D, which better approximates the enhanced polarity in condensed phases compared to three-site models.[19] The seminal TIP4P model, introduced in 1983, uses OH bond length of 0.9572 Å, H-O-H angle of 104.52°, M-site displacement of 0.15 Å, q_H = +0.52 e, q_M = -1.04 e, and oxygen Lennard-Jones parameters σ = 3.1536 Å, ε = 0.155 kcal/mol. This model provides reasonable descriptions of liquid water's structure and thermodynamics at ambient conditions, with oxygen-oxygen radial distribution functions aligning well with neutron scattering data. Subsequent refinements addressed limitations in phase behavior and electrostatic treatment. The TIP4P/2005 model (2005) reparameterizes the original with q_H = +0.5564 e, q_M = -1.1128 e, M-site displacement of 0.1546 Å, and oxygen Lennard-Jones parameters σ = 3.1589 Å, ε/k_B = 93.2 K (≈0.185 kcal/mol), optimizing for liquid density anomalies, isothermal compressibility, and the phase diagram. It predicts a melting point of ice I_h at approximately 250 K (versus experimental 273 K) and accurately reproduces multiple ice polymorphs and the liquid-vapor coexistence curve. The TIP4P-Ew variant (2004) adjusts for compatibility with Ewald summation methods used in biomolecular simulations, featuring q_H = +0.52422 e, q_M = -1.04844 e, M-site displacement of 0.125 Å, and oxygen Lennard-Jones parameters σ = 3.16435 Å, ε = 0.16275 kcal/mol; it improves bulk properties like density maximum near 1 °C and enthalpy of vaporization across the liquid range. The OPC model (2014) employs an optimization of charge placement without rigid geometric constraints beyond symmetry, yielding q_H = +0.6791 e, q_M = -1.3582 e, OH bond length of 0.8724 Å, H-O-H angle of 103.6°, M-site displacement of 0.1594 Å, and oxygen Lennard-Jones parameters σ = 3.166 Å, ε = 0.2128 kcal/mol; this enhances transferability across properties like solvation free energies and dielectric constant.[20] Notable variants include TIP4P/Ice (2005), tailored for supercooled water and ice phases with adjusted Lennard-Jones ε/k_B = 106 K to better match ice densities and melting behavior at 272 K. The TIP4P-D model (2015) incorporates an empirical dispersion correction to the Lennard-Jones term, improving predictions of solvation properties and structural features in protein environments without altering core electrostatics. These models excel over three-site counterparts by mitigating inaccuracies in tetrahedral coordination and dipole representation through the off-center negative charge, yielding superior liquid structure, phase equilibria, and ice properties while maintaining computational efficiency.| Model | Year | q_H (e) | M displacement (Å) | σ_O (Å) | ε_O (kcal/mol) | Key Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIP4P | 1983 | +0.52 | 0.15 | 3.1536 | 0.155 | Liquid structure/thermodynamics |

| TIP4P/2005 | 2005 | +0.5564 | 0.1546 | 3.1589 | 0.185 | Phase diagram/anomalies |

| TIP4P-Ew | 2004 | +0.52422 | 0.125 | 3.16435 | 0.16275 | Ewald sums/biomolecules |

| OPC | 2014 | +0.6791 | 0.1594 | 3.166 | 0.2128 | Transferability/solvation[20] |