Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ocean temperature

View on Wikipedia

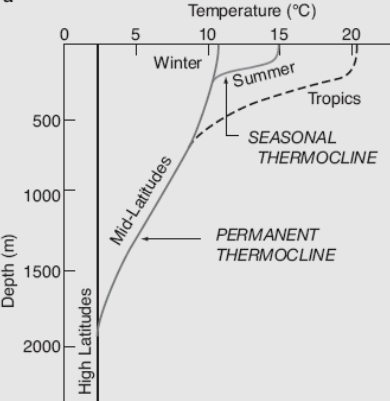

The ocean temperature plays a crucial role in the global climate system, ocean currents and for marine habitats. It varies depending on depth, geographical location and season. Not only does the temperature differ in seawater, so does the salinity. Warm surface water is generally saltier than the cooler deep or polar waters.[1] In polar regions, the upper layers of ocean water are cold and fresh.[2] Deep ocean water is cold, salty water found deep below the surface of Earth's oceans. This water has a uniform temperature of around 0-3 °C.[3] The ocean temperature also depends on the amount of solar radiation falling on its surface. In the tropics, with the Sun nearly overhead, the temperature of the surface layers can rise to over 30 °C (86 °F). Near the poles the temperature in equilibrium with the sea ice is about −2 °C (28 °F).

There is a continuous large-scale circulation of water in the oceans. One part of it is the thermohaline circulation (THC). It is driven by global density gradients created by surface heat and freshwater fluxes.[4][5] Warm surface currents cool as they move away from the tropics. This happens as the water becomes denser and sinks. Changes in temperature and density move the cold water back towards the equator as a deep sea current. Then it eventually wells up again towards the surface.

Ocean temperature as a term applies to the temperature in the ocean at any depth. It can also apply specifically to the ocean temperatures that are not near the surface. In this case it is synonymous with deep ocean temperature).

It is clear that the oceans are warming as a result of climate change and this rate of warming is increasing.[6]: 9 [7] The upper ocean (above 700 m) is warming fastest, but the warming trend extends throughout the ocean. In 2022, the global ocean was the hottest ever recorded by humans.[8]

Definition and types

[edit]Sea surface temperature

[edit]

Deep ocean temperature

[edit]Experts refer to the temperature further below the surface as ocean temperature or deep ocean temperature. Ocean temperatures more than 20 metres below the surface vary by region and time. They contribute to variations in ocean heat content and ocean stratification.[11] The increase of both ocean surface temperature and deeper ocean temperature is an important effect of climate change on oceans.[11]

Deep ocean water is the name for cold, salty water found deep below the surface of Earth's oceans. Deep ocean water makes up about 90% of the volume of the oceans. Deep ocean water has a very uniform temperature of around 0-3 °C. Its salinity is about 3.5% or 35 ppt (parts per thousand).[3]

Relevance

[edit]Ocean temperature and dissolved oxygen concentrations have a big influence on many aspects of the ocean. These two key parameters affect the ocean's primary productivity, the oceanic carbon cycle, nutrient cycles, and marine ecosystems.[12] They work in conjunction with salinity and density to control a range of processes. These include mixing versus stratification, ocean currents and the thermohaline circulation.[citation needed]

Ocean heat content

[edit]Experts calculate ocean heat content by using ocean temperatures at different depths.

Ocean heat content (OHC) or ocean heat uptake (OHU) is the energy absorbed and stored by oceans.[14] It is an important indicator of global warming.[15] Ocean heat content is calculated by measuring ocean temperature at many different locations and depths, and integrating the areal density of a change in enthalpic energy over an ocean basin or entire ocean.[16]

Between 1971 and 2018, a steady upward trend[17] in ocean heat content accounted for over 90% of Earth's excess energy from global warming.[18][19] Scientists estimate a 1961–2022 warming trend of 0.43 ± 0.08 W/m², accelerating at about 0.15 ± 0.04 W/m² per decade.[20] By 2020, about one third of the added energy had propagated to depths below 700 meters.[21][22] The five highest ocean heat observations to a depth of 2000 meters all occurred in the period 2020–2024.[17] The main driver of this increase has been human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.[23]: 1228Measurements

[edit]There are various ways to measure ocean temperature.[24] Below the sea surface, it is important to refer to the specific depth of measurement as well as measuring the general temperature. The reason is there is a lot of variation with depths. This is especially the case during the day. At this time low wind speed and a lot of sunshine may lead to the formation of a warm layer at the ocean surface and big changes in temperature as you get deeper. Experts call these strong daytime vertical temperature gradients a diurnal thermocline.[25]

The basic technique involves lowering a device to measure temperature and other parameters electronically. This device is called CTD which stands for conductivity, temperature, and depth.[26] It continuously sends the data up to the ship via a conducting cable. This device is usually mounted on a frame that includes water sampling bottles. Since the 2010s autonomous vehicles such as gliders or mini-submersibles have been increasingly available. They carry the same CTD sensors, but operate independently of a research ship.

Scientists can deploy CTD systems from research ships on moorings gliders and even on seals.[27] With research ships they receive data through the conducting cable. For the other methods they use telemetry.

There are other ways of measuring sea surface temperature.[28] At this near-surface layer measurements are possible using thermometers or satellites with spectroscopy. Weather satellites have been available to determine this parameter since 1967. Scientists created the first global composites during 1970.[29]

The Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) is widely used to measure sea surface temperature from space.[24]: 90

There are various devices to measure ocean temperatures at different depths. These include the Nansen bottle, bathythermograph, CTD, or ocean acoustic tomography. Moored and drifting buoys also measure sea surface temperatures. Examples are those deployed by the Global Drifter Program and the National Data Buoy Center. The World Ocean Database Project is the largest database for temperature profiles from all of the world's oceans.[30]

A small test fleet of deep Argo floats aims to extend the measurement capability down to about 6000 meters. It will accurately sample temperature for a majority of the ocean volume once it is in full use.[31][32]

The most frequent measurement technique on ships and buoys is thermistors and mercury thermometers.[24]: 88 Scientists often use mercury thermometers to measure the temperature of surface waters. They can put them in buckets dropped over the side of a ship. To measure deeper temperatures they put them on Nansen bottles.[24]: 88

Monitoring through Argo program

[edit]Ocean warming

[edit]

Trends

[edit]It is clear that the ocean is warming as a result of climate change, and this rate of warming is increasing.[36]: 9 The global ocean was the warmest it had ever been recorded by humans in 2022.[37] This is determined by the ocean heat content, which exceeded the previous 2021 maximum in 2022.[37] The steady rise in ocean temperatures is an unavoidable result of the Earth's energy imbalance, which is primarily caused by rising levels of greenhouse gases.[37] Between pre-industrial times and the 2011–2020 decade, the ocean's surface has heated between 0.68 and 1.01 °C.[38]: 1214

The majority of ocean heat gain occurs in the Southern Ocean. For example, between the 1950s and the 1980s, the temperature of the Antarctic Southern Ocean rose by 0.17 °C (0.31 °F), nearly twice the rate of the global ocean.[39]

The warming rate varies with depth. The upper ocean (above 700 m) is warming the fastest. At an ocean depth of a thousand metres the warming occurs at a rate of nearly 0.4 °C per century (data from 1981 to 2019).[40]: Figure 5.4 In deeper zones of the ocean (globally speaking), at 2000 metres depth, the warming has been around 0.1 °C per century.[40]: Figure 5.4 The warming pattern is different for the Antarctic Ocean (at 55°S), where the highest warming (0.3 °C per century) has been observed at a depth of 4500 m.[40]: Figure 5.4Overall, scientists project that all regions of the oceans will warm by 2050, but models disagree for SST changes expected in the subpolar North Atlantic, the equatorial Pacific, and the Southern Ocean.[41] The future global mean SST increase for the period 1995-2014 to 2081-2100 is 0.86 °C under the most modest greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, and up to 2.89 °C under the most severe emissions scenarios.[41]

A study published in 2025 in Environmental Research Letters reported that global mean sea surface temperature increases had more than quadrupled, from 0.06 K per decade during 1985–89 to 0.27 K per decade for 2019–23.[42] The researchers projected that the increase inferred over the past 40 years would likely be exceeded within the next 20 years.[42]Causes

[edit]The cause of recent observed changes is the warming of the Earth due to human-caused emissions of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane.[43] Growing concentrations of greenhouse gases increases Earth's energy imbalance, further warming surface temperatures.[8] The ocean takes up most of the added heat in the climate system, raising ocean temperatures.[7]

Main physical effects

[edit]Increased stratification and lower oxygen levels

[edit]Higher air temperatures warm the ocean surface. And this leads to greater ocean stratification. Reduced mixing of the ocean layers stabilises warm water near the surface. At the same time it reduces cold, deep water circulation. The reduced up and down mixing reduces the ability of the ocean to absorb heat. This directs a larger fraction of future warming toward the atmosphere and land. Energy available for tropical cyclones and other storms is likely to increase. Nutrients for fish in the upper ocean layers are set to decrease. This is also like to reduce the capacity of the oceans to store carbon.[citation needed]

Warmer water cannot contain as much oxygen as cold water. Increased thermal stratification may reduce the supply of oxygen from the surface waters to deeper waters. This would further decrease the water's oxygen content.[44] This process is called ocean deoxygenation. The ocean has already lost oxygen throughout the water column. Oxygen minimum zones are expanding worldwide.[45]: 471

Changing ocean currents

[edit]Varying temperatures associated with sunlight and air temperatures at different latitudes cause ocean currents. Prevailing winds and the different densities of saline and fresh water are another cause of currents. Air tends to be warmed and thus rise near the equator, then cool and thus sink slightly further poleward. Near the poles, cool air sinks, but is warmed and rises as it then travels along the surface equatorward. The sinking and upwelling that occur in lower latitudes, and the driving force of the winds on surface water, mean the ocean currents circulate water throughout the entire sea. Global warming on top of these processes causes changes to currents, especially in the regions where deep water is formed.[46]

In the geologic past

[edit]Scientists believe the sea temperature was much hotter in the Precambrian period. Such temperature reconstructions derive from oxygen and silicon isotopes from rock samples.[47][48] These reconstructions suggest the ocean had a temperature of 55–85 °C 2,000 to 3,500 million years ago. It then cooled to milder temperatures of between 10 and 40 °C by 1,000 million years ago. Reconstructed proteins from Precambrian organisms also provide evidence that the ancient world was much warmer than today.[49][50]

The Cambrian Explosion approximately 538.8 million years ago was a key event in the evolution of life on Earth. This event took place at a time when scientists believe sea surface temperatures reached about 60 °C.[51] Such high temperatures are above the upper thermal limit of 38 °C for modern marine invertebrates. They preclude a major biological revolution.[52]

During the later Cretaceous period, from 100 to 66 million years ago, average global temperatures reached their highest level in the last 200 million years or so.[53] This was probably the result of the configuration of the continents during this period. It allowed for improved circulation in the oceans. This discouraged the formation of large scale ice sheet.[54]

Data from an oxygen isotope database indicate that there have been seven global warming events during the geologic past. These include the Late Cambrian, Early Triassic, Late Cretaceous, and Paleocene-Eocene transition. The surface of the sea was about 5-30º warmer than today in these warming periods.[12]

See also

[edit]- Global surface temperature – Average temperature of the Earth's surface

- Marine heatwave – Unusually warm temperature event in the ocean

- Ocean current – Directional mass flow of oceanic water

- Sea surface skin temperature – Quantity in oceanography

- Upwelling – Oceanographic phenomenon of wind-driven motion of ocean water

References

[edit]- ^ "Ocean Stratification". The Climate System. Columbia Univ. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ "The Hidden Meltdown of Greenland". Nasa Science/Science News. NASA. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Temperature of Ocean Water". UCAR. Archived from the original on 2010-03-27. Retrieved 2012-09-05.

- ^ Rahmstorf, S (2003). "The concept of the thermohaline circulation" (PDF). Nature. 421 (6924): 699. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..699R. doi:10.1038/421699a. PMID 12610602. S2CID 4414604.

- ^ Lappo, SS (1984). "On reason of the northward heat advection across the Equator in the South Pacific and Atlantic ocean". Study of Ocean and Atmosphere Interaction Processes. Moscow Department of Gidrometeoizdat (in Mandarin): 125–9.

- ^ IPCC, 2019: Summary for Policymakers Archived 2022-10-18 at the Wayback Machine. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate Archived 2021-07-12 at the Wayback Machine [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.001.

- ^ a b Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Hausfather, Zeke; Trenberth, Kevin E. (2019). "How fast are the oceans warming?". Science. 363 (6423): 128–129. Bibcode:2019Sci...363..128C. doi:10.1126/science.aav7619. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30630919. S2CID 57825894.

- ^ a b Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Mann, Michael E.; Zhu, Jiang; Wang, Fan; Locarnini, Ricardo; Li, Yuanlong; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Feng, Licheng (2023). "Another Year of Record Heat for the Oceans". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 40 (6): 963–974. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2. ISSN 0256-1530. PMC 9832248. PMID 36643611.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ "Copernicus: March 2024 is the tenth month in a row to be the hottest on record | Copernicus". climate.copernicus.eu. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ Rahmstorf, S (2003). "The concept of the thermohaline circulation" (PDF). Nature. 421 (6924): 699. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..699R. doi:10.1038/421699a. PMID 12610602. S2CID 4414604.

- ^ a b Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change Archived 2022-10-24 at the Wayback Machine. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Archived 2021-08-09 at the Wayback Machine [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011

- ^ a b Song, Haijun; Wignall, Paul B.; Song, Huyue; Dai, Xu; Chu, Daoliang (2019). "Seawater Temperature and Dissolved Oxygen over the Past 500 Million Years". Journal of Earth Science. 30 (2): 236–243. doi:10.1007/s12583-018-1002-2. ISSN 1674-487X. S2CID 146378272.

- ^ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann (6 September 2023). "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. ● Top 2000 meters: "Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023.

- ^ US EPA (2016-06-27). "Climate Change Indicators: Ocean Heat". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2025-06-22.

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Foster, Grant; Hausfather, Zeke; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Abraham, John (2022). "Improved Quantification of the Rate of Ocean Warming". Journal of Climate. 35 (14): 4827–4840. Bibcode:2022JCli...35.4827C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0895.1.

- ^ Dijkstra, Henk A. (2008). Dynamical oceanography ([Corr. 2nd print.] ed.). Berlin: Springer Verlag. p. 276. ISBN 9783540763758.

- ^ a b NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Assessing the Global Climate in 2024, published online January 2025, Retrieved on March 2, 2025 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/global-climate-202413.

- ^ von Schuckmann, K.; Cheng, L.; Palmer, M. D.; Hansen, J.; et al. (7 September 2020). "Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go?". Earth System Science Data. 12 (3): 2013–2041. Bibcode:2020ESSD...12.2013V. doi:10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020. hdl:20.500.11850/443809.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Locarnini, Ricardo; et al. (2021). "Upper Ocean Temperatures Hit Record High in 2020". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 38 (4): 523–530. Bibcode:2021AdAtS..38..523C. doi:10.1007/s00376-021-0447-x. S2CID 231672261.

- ^ Storto, Andrea; Yang, Chunxue (2024). "Acceleration of the ocean warming from 1961 to 2022 unveiled by large-ensemble reanalyses". Nature Communications. 15 (545): 545. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15..545S. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-44749-7. PMC 10791650. PMID 38228601.

- ^ LuAnn Dahlman and Rebecca Lindsey (2020-08-17). "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013.

- ^ "Study: Deep Ocean Waters Trapping Vast Store of Heat". Climate Central. 2016.

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change Archived 2022-10-24 at the Wayback Machine. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Archived 2021-08-09 at the Wayback Machine [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

- ^ a b c d "Introduction to Physical Oceanography". Open Textbook Library. 2008. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- ^ Vittorio Barale (2010). Oceanography from Space: Revisited. Springer. p. 263. ISBN 978-90-481-8680-8.

- ^ "Conductivity, Temperature, Depth (CTD) Sensors - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution". www.whoi.edu/. Retrieved 2023-03-06.

- ^ Boyd, I.L; Hawker, E.J; Brandon, M.A; Staniland, I.J (2001). "Measurement of ocean temperatures using instruments carried by Antarctic fur seals". Journal of Marine Systems. 27 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1016/S0924-7963(00)00073-7.

- ^ Alexander Soloviev; Roger Lukas (2006). The near-surface layer of the ocean: structure, dynamics and applications. シュプリンガー・ジャパン株式会社. p. xi. Bibcode:2006nslo.book.....S. ISBN 978-1-4020-4052-8.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ P. Krishna Rao; W. L. Smith; R. Koffler (January 1972). "Global Sea-Surface Temperature Distribution Determined From an Environmental Satellite". Monthly Weather Review. 100 (1): 10–14. Bibcode:1972MWRv..100...10K. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1972)100<0010:GSTDDF>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ "World Ocean Database Profiles the Ocean". National Centers for Environmental Information. 14 June 2017.

- ^ Administration, US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric. "Deep Argo". oceantoday.noaa.gov. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Deep Argo: Diving for Answers in the Ocean's Abyss". www.climate.gov. 24 December 2021. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015.

- ^ Argo Begins Systematic Global Probing of the Upper Oceans Toni Feder, Phys. Today 53, 50 (2000), Archived 11 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine doi:10.1063/1.1292477

- ^ Richard Stenger (19 September 2000). "Flotilla of sensors to monitor world's oceans". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 November 2007.

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Zhu, Jiang; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Locarnini, Ricardo; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Song, Xiangzhou; Liu, Yulong; Mann, Michael E. (2020). "Record-Setting Ocean Warmth Continued in 2019". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 37 (2): 137–142. Bibcode:2020AdAtS..37..137C. doi:10.1007/s00376-020-9283-7. ISSN 1861-9533. S2CID 210157933.

- ^ "Summary for Policymakers". The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (PDF). 2019. pp. 3–36. doi:10.1017/9781009157964.001. ISBN 978-1-00-915796-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ a b c Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Mann, Michael E.; Zhu, Jiang; Wang, Fan; Locarnini, Ricardo; Li, Yuanlong; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Feng, Licheng (2023). "Another Year of Record Heat for the Oceans". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 40 (6): 963–974. Bibcode:2023AdAtS..40..963C. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2. ISSN 0256-1530. PMC 9832248. PMID 36643611. Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change Archived 2022-10-24 at the Wayback Machine. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Archived 2021-08-09 at the Wayback Machine [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362

- ^ Gille, Sarah T. (2002-02-15). "Warming of the Southern Ocean Since the 1950s". Science. 295 (5558): 1275–1277. Bibcode:2002Sci...295.1275G. doi:10.1126/science.1065863. PMID 11847337. S2CID 31434936.

- ^ a b c Bindoff, N.L., W.W.L. Cheung, J.G. Kairo, J. Arístegui, V.A. Guinder, R. Hallberg, N. Hilmi, N. Jiao, M.S. Karim, L. Levin, S. O'Donoghue, S.R. Purca Cuicapusa, B. Rinkevich, T. Suga, A. Tagliabue, and P. Williamson, 2019: Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities Archived 2019-12-20 at the Wayback Machine. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate Archived 2021-07-12 at the Wayback Machine [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

- ^ a b Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, New York, USA, pages 1211–1362, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.011.

- ^ a b Merchant, Christopher J.; Allan, Richard P.; Embury, Owen (28 January 2025). "Quantifying the acceleration of multidecadal global sea surface warming driven by Earth's energy imbalance". Environmental Research Letters. 20 (2): 024037. Bibcode:2025ERL....20b4037M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/adaa8a.

- ^ Doney, Scott C.; Busch, D. Shallin; Cooley, Sarah R.; Kroeker, Kristy J. (2020-10-17). "The Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Marine Ecosystems and Reliant Human Communities". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 45 (1): 83–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012320-083019. ISSN 1543-5938. (CC BY 4.0 International license)

- ^ Chester, R.; Jickells, Tim (2012). "Chapter 9: Nutrients oxygen organic carbon and the carbon cycle in seawater". Marine geochemistry (3rd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley/Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-34909-0. OCLC 781078031.

- ^ Bindoff, N.L., W.W.L. Cheung, J.G. Kairo, J. Arístegui, V.A. Guinder, R. Hallberg, N. Hilmi, N. Jiao, M.S. Karim, L. Levin, S. O'Donoghue, S.R. Purca Cuicapusa, B. Rinkevich, T. Suga, A. Tagliabue, and P. Williamson, 2019: Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities Archived 2019-12-20 at the Wayback Machine. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate Archived 2021-07-12 at the Wayback Machine [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)]. In press.

- ^ Trenberth, K; Caron, J (2001). "Estimates of Meridional Atmosphere and Ocean Heat Transports". Journal of Climate. 14 (16): 3433–43. Bibcode:2001JCli...14.3433T. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<3433:EOMAAO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Knauth, L. Paul (2005). "Temperature and salinity history of the Precambrian ocean: implications for the course of microbial evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 219 (1–2): 53–69. Bibcode:2005PPP...219...53K. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.10.014.

- ^ Shields, Graham A.; Kasting, James F. (2006). "A palaeotemperature curve for the Precambrian oceans based on silicon isotopes in cherts". Nature. 443 (7114): 969–972. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..969R. doi:10.1038/nature05239. PMID 17066030. S2CID 4417157.

- ^ Gaucher, EA; Govindarajan, S; Ganesh, OK (2008). "Palaeotemperature trend for Precambrian life inferred from resurrected proteins". Nature. 451 (7179): 704–707. Bibcode:2008Natur.451..704G. doi:10.1038/nature06510. PMID 18256669. S2CID 4311053.

- ^ Risso, VA; Gavira, JA; Mejia-Carmona, DF (2013). "Hyperstability and substrate promiscuity in laboratory resurrections of Precambrian b-lactamases". J Am Chem Soc. 135 (8): 2899–2902. doi:10.1021/ja311630a. hdl:11336/22624. PMID 23394108.

- ^ Wotte, Thomas; Skovsted, Christian B.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Kouchinsky, Artem (2019). "Isotopic evidence for temperate oceans during the Cambrian Explosion". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 6330. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.6330W. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6474879. PMID 31004083.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wotte, Thomas; Skovsted, Christian B.; Whitehouse, Martin J.; Kouchinsky, Artem (2019). "Isotopic evidence for temperate oceans during the Cambrian Explosion". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 6330. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.6330W. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42719-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6474879. PMID 31004083.

- ^ Renne, Paul R.; Deino, Alan L.; Hilgen, Frederik J.; Kuiper, Klaudia F.; Mark, Darren F.; Mitchell, William S.; Morgan, Leah E.; Mundil, Roland; Smit, Jan (7 February 2013). "Time Scales of Critical Events Around the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary". Science. 339 (6120): 684–687. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..684R. doi:10.1126/science.1230492. PMID 23393261. S2CID 6112274.

- ^ Beltran, Catherine; Golledge, Nicholas R.; Ohneiser, Christian; Kowalewski, Douglas E.; Sicre, Marie-Alexandrine; Hageman, Kimberly J.; Smith, Robert; Wilson, Gary S.; Mainié, François (2020-01-15). "Southern Ocean temperature records and ice-sheet models demonstrate rapid Antarctic ice sheet retreat under low atmospheric CO2 during Marine Isotope Stage 31". Quaternary Science Reviews. 228 106069. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106069. ISSN 0277-3791.

Ocean temperature

View on GrokipediaFundamental Concepts

Definitions and Classifications

Ocean temperature refers to the thermal state of seawater, quantified in degrees Celsius (°C), with global ranges typically from -2°C in polar deep waters to over 30°C in tropical surface layers.[8][9] This parameter influences water density, circulation, and marine ecosystems through its interaction with salinity and pressure. Measurements distinguish between in-situ temperature, recorded at depth under ambient pressure, and potential temperature, the value the water parcel would attain if adiabatically transported to the sea surface without heat exchange.[10] A more thermodynamically consistent metric, conservative temperature, approximates the internal energy per unit mass and differs from potential temperature by up to 1°C in warm, fresh waters but remains within ±0.05°C for most oceanic conditions.[10] Sea surface temperature (SST) specifically denotes the temperature of the ocean's uppermost layer, from the skin (top few millimeters) to depths of up to 20 meters, directly affecting air-sea heat fluxes and atmospheric dynamics.[11][12] Vertically, ocean temperature exhibits a stratified structure: the surface mixed layer, where turbulence homogenizes temperatures; the thermocline, a transitional zone of sharp gradient (often 500–1,000 meters thick) separating warmer surface waters from colder depths; and the deep ocean, where temperatures stabilize near 0–4°C with minimal variation.[13][14] The thermocline's depth and intensity vary seasonally and latitudinally, deepening in tropics and shoaling in mid-latitudes during summer.[15] Ocean waters are classified into water masses based on characteristic temperature-salinity (T-S) signatures acquired during formation in source regions, enabling identification via T-S diagrams.[16][17] These include surface waters like subtropical mode waters (warm, saline), intermediate waters such as Antarctic Intermediate Water (cooler, fresher), and deep waters like North Atlantic Deep Water (around 2–4°C, high salinity) or Antarctic Bottom Water (near -0.5°C, oxygen-rich).[18] Such classifications trace thermohaline circulation pathways, as water masses conserve their properties adiabatically until mixing occurs.[16] Horizontally, temperatures are zoned by latitude, with equatorial bands exceeding 25°C, subtropical gyres around 15–20°C, and polar regions below 5°C, modulated by currents and upwelling.[8]Thermodynamic Role in Climate System

Water's specific heat capacity of approximately 4.18 J/g·°C enables the oceans to store vast amounts of thermal energy with minimal temperature fluctuations, far exceeding the atmosphere's capacity of about 1.0 J/g·°C for dry air.[19] [20] Seawater's effective heat capacity, around 3,900 J/kg·°C, combined with the oceans' volume—covering 71% of Earth's surface and extending to average depths of 3,700 meters—results in the ocean holding roughly 1,000 times the heat capacity of the entire atmosphere.[21] [22] This thermodynamic property positions the oceans as the primary heat reservoir in the climate system, absorbing solar radiation and modulating global energy distribution.[23] Since the mid-20th century, oceans have sequestered over 90% of excess heat from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, with ocean heat content reaching record levels by 2023.[24] [25] This uptake, quantified through integrated measurements to depths of 2,000 meters, buffers atmospheric temperature rises but drives thermal expansion contributing to sea level increase.[26] The ocean's thermal inertia delays full climate responses to radiative forcing, stabilizing short-term variability while amplifying long-term changes through feedbacks like altered circulation.[27] Ocean currents, propelled by density gradients from temperature and salinity variations, transport heat poleward at rates up to 1 petawatt in the Atlantic, reducing equator-to-pole temperature contrasts that would otherwise prevail under atmospheric transport alone.[28] [29] The thermohaline circulation, including components like the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, redistributes this heat vertically and horizontally, influencing regional climates and atmospheric circulation patterns such as Hadley cells.[22] Surface ocean temperatures also regulate evaporation and latent heat fluxes to the atmosphere, fueling phenomena like monsoons and hurricanes while exerting a thermostat effect that tempers extreme warming in tropical regions.[30] Disruptions to these dynamics, such as from freshwater influx, could weaken heat transport and exacerbate polar amplification.[31]Observation Methods

Historical Approaches

Early observations of ocean temperature focused on sea surface temperature (SST), with systematic measurements commencing in the late 18th century using mercury thermometers inserted into water samples hauled aboard ships via buckets or directly suspended overboard.[32] These initial efforts, driven by scientific curiosity rather than routine monitoring, provided sparse data primarily from exploratory voyages.[32] By the 19th century, the bucket method became standardized, involving wooden or canvas receptacles lowered to the sea surface, filled with seawater, and then measured promptly with unprotected or protected mercury thermometers to minimize exposure time and evaporative cooling biases.[33] Wooden buckets, common until the early 20th century, induced greater temperature depression (up to 0.5–1°C) due to slower hauling and higher heat loss compared to later canvas or uninsulated rubber variants.[34] Data collection expanded through merchant and naval logs, such as those from the British Royal Navy and whaling ships, yielding datasets like the International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS) precursors with coverage increasing from fewer than 1,000 observations annually in 1850 to over 100,000 by 1900.[35] Subsurface temperature profiling emerged in the late 19th century with the development of reversing thermometers by François-Alphonse Forel in 1877 and their integration into Nansen bottles by Fridtjof Nansen around 1900, allowing protected deep-water samples to be isolated at depth and measured upon retrieval without pressure distortion.[36] These mechanical samplers, deployed via hydrographic casts, enabled vertical profiles to depths of several thousand meters, though resolution remained coarse (typically 10–20 depths per cast) and labor-intensive, limiting frequency to dedicated expeditions like the 1872–1876 Challenger voyage, which recorded over 350 stations.[37] From the 1930s onward, shipboard methods evolved with the adoption of engine-room intake thermometers, which sampled water piped for cooling at 2–10 meters depth, reducing bucket-related artifacts but introducing hull-induced warming biases of 0.2–0.5°C; this transition coincided with World War II expansions in naval observations.[38] Auxiliary techniques included mechanical bathythermographs (MBTs) from the 1930s, which traced shallow profiles (to 200–300 meters) via towed or lowered probes, and early radiation thermometers for non-contact SST estimates, though these were sporadic until post-1940s refinements.[33] Overall, pre-1950 records suffered from inhomogeneous coverage, with northern hemisphere biases and seasonal gaps, necessitating subsequent adjustments for instrument and platform shifts to reconstruct reliable baselines.[35]Modern Instrumentation and Satellites

Modern satellite observations of sea surface temperature (SST) primarily utilize infrared radiometers and microwave sensors to infer skin-layer temperatures from thermal emissions, with corrections for atmospheric effects such as water vapor and aerosols. The Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR), operational on NOAA polar-orbiting satellites since the late 1970s and continued on platforms like MetOp-A/B/C, provides global SST data at spatial resolutions of approximately 1 km, aggregated into daily 0.25° grid products with accuracies around 0.02 K against buoy validations, though standard deviations reach 0.25 K due to cloud contamination and diurnal variability.[39][40] Blended analyses, such as NOAA's Optimum Interpolation SST (OISST), integrate AVHRR with microwave data from instruments like the Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-EOS (AMSR-E) on Aqua (launched 2002) to mitigate cloud biases, achieving near-daily global coverage between 60°S and 60°N.[41][42] Subsurface temperature profiling relies on autonomous platforms, notably the Argo array, which deploys over 3,900 profiling floats globally since full implementation around 2004, following initial deployments in 1999. These neutrally buoyant floats drift at depth, ascend to the surface every 10 days to measure temperature and salinity profiles from 2,000 m to the surface using embedded conductivity-temperature-depth (CTD) sensors, providing unprecedented three-dimensional coverage of the upper ocean with vertical resolutions of 10-20 m and uncertainties typically below 0.002°C for temperature.[43][44] Argo data, disseminated in near real-time, cover ice-free regions poleward to about 80° latitude, enabling quantification of heat content anomalies with basin-scale precision.[45] Complementary instrumentation includes shipborne CTD rosettes, which deploy sensor arrays to sample full-depth profiles with accuracies of 0.001°C for temperature via platinum resistance thermometers, often integrated with oxygen and bio-optical sensors for contextual validation.[46] Autonomous underwater gliders, equipped with miniaturized CTDs (e.g., 1-2 mm diameter sensors), execute sawtooth dives to 1,000 m or more, yielding hourly profiles over missions lasting weeks to months, with temperature precisions around 0.002°C, enhancing spatial sampling in dynamic regions like coastal upwelling zones.[47] Moored buoys, such as those in NOAA's Tropical Atmosphere Ocean array, provide time-series measurements at fixed depths using ruggedized CTDs, logging data at intervals of minutes to hours with minimal drift over multi-year deployments.[48] These systems collectively address satellite limitations in subsurface access and polar/near-coastal gaps, though calibration against in-situ references remains essential to counter sensor biofouling and instrumental biases.[49]Data Quality Assessments

In situ sea surface temperature (SST) measurements face multiple sources of uncertainty, including instrumental errors, sampling biases, and environmental factors such as sensor exposure to air or deck heating. A comprehensive review identifies key components: random measurement errors (typically 0.1–0.5°C for historical buckets), systematic biases from method transitions (e.g., uninsulated to insulated buckets or ship engine intakes), and spatial undersampling leading to interpolation uncertainties. These contribute to overall SST dataset uncertainties of approximately 0.1°C for global means in recent decades, escalating to 0.2–0.5°C in the early 20th century due to sparse coverage and unadjusted cooling biases from canvas bucket evaporation.[32][50] Homogenization adjustments aim to correct for these inhomogeneities but introduce their own uncertainties, often comparable to observed decadal variability. For instance, datasets like HadSST and ERSST apply time-dependent bias corrections for bucket types and intake depths, yet unresolved differences persist across products, with early-20th-century SSTs potentially underestimated by 0.2–0.4°C due to inadequate canvas bucket insulation modeling. Independent analyses using instrumentally homogeneous subsets confirm post-1950 warming trends of 0.07–0.1°C per decade but highlight larger error bars (up to 0.3°C) before 1940 from uncorrected wartime disruptions and measurement practice shifts.[51][52][53] Subsurface temperature data from ARGO floats undergo rigorous real-time and delayed-mode quality control to flag outliers, spikes, and drifts, with typical single-measurement accuracies of 0.002°C after corrections for sensor response times and thermal lags. However, systematic issues like conductivity cell fouling or pressure sensor drifts can propagate to temperature via salinity-derived density effects, necessitating expert adjustments in delayed-mode processing; uncorrected floats may exhibit biases up to 0.01°C in deep profiles. Coverage remains uneven in polar regions and marginal seas, amplifying gridding uncertainties in global products.[54][55] Ocean heat content (OHC) estimates integrate these temperature profiles with depth-dependent uncertainties, historically inflated by expendable bathythermograph (XBT) fall-rate biases (up to 10% depth errors) and sparse sampling pre-ARGO. Modern assessments quantify OHC uncertainties at 0.5–1.0 × 10^{22} J for upper 2000 m since 2005, driven by profile-to-grid mapping and end-member assumptions in objective analyses, though ARGO has reduced them by an order of magnitude compared to 1970s-era ship casts. The International Quality-controlled Ocean Database (IQuOD) standardizes flags and uncertainty propagation across profiles, revealing that deep-ocean (>2000 m) trends carry higher relative errors (0.1–0.5°C per century) due to limited observations and model-derived interpolations.[56][57][58]Patterns of Variability

Spatial Gradients and Zonation

Ocean temperature displays marked spatial gradients horizontally across latitudes and vertically through depth, delineating distinct thermal zonations that influence circulation, ecosystems, and heat transport. The dominant horizontal gradient is latitudinal, with sea surface temperatures (SSTs) averaging 25–30°C near the equator—peaking around 28–29°C in the western equatorial Pacific—and declining poleward to approximately -1.8°C in polar regions, reflecting the cosine variation in solar insolation with latitude.[2] This equator-to-pole SST contrast, typically 25–30°C globally, steepens in winter hemispheres due to seasonal cooling and is modulated by ocean currents; for instance, the Gulf Stream elevates mid-latitude North Atlantic SSTs by 5–10°C relative to zonal averages.[59] In the Southern Hemisphere, the gradient is more symmetric and pronounced owing to the encircling Southern Ocean, whereas Northern Hemisphere landmasses introduce longitudinal asymmetries, such as cooler eastern boundaries from upwelling.[60] Vertically, the ocean stratifies into three primary thermal zones: the surface mixed layer (0–50 to 200 m depth, depending on latitude and season), where temperatures align closely with SSTs and uniformity prevails due to wind-driven mixing; the thermocline (often 100–1000 m), characterized by a sharp gradient of 0.01–0.1°C per meter dropping from ~20°C to 5–10°C; and the deep ocean below (~1000 m to abyss), maintaining near-uniform temperatures of 1–4°C with gradients under 0.001°C/m, as adiabatic compression and diffusion homogenize heat.[61] Thermocline depth and intensity vary zonally: in tropical oceans, a permanent thermocline resides at 100–200 m, enabling efficient heat trapping; subtropical gyres deepen it to 500–1000 m with weaker gradients; polar regions feature seasonal absence of a distinct thermocline, with winter convection mixing to 500–1000 m depths, erasing gradients until summer restratification.[62] These vertical zonations arise from surface heating, radiative cooling, and salinity effects on density, with the 20°C isotherm often defining the thermocline base in equatorial profiles.[63] Horizontal zonation beyond latitude includes coastal-offshore and frontal structures; eastern boundary upwelling zones, like Peru or California currents, sustain 5–15°C cooler SSTs than adjacent open ocean due to Ekman transport lifting cold deep water, forming persistent thermal fronts with gradients exceeding 1°C/km.[64] Conversely, western boundary currents such as the Kuroshio or Brazil Current intensify warm gradients, transporting equatorial heat poleward at rates enhancing meridional heat flux by factors of 2–5 over diffusive estimates. Subtropical gyre interiors exhibit subdued gradients, with SSTs 1–3°C warmer than gyre edges from downwelling suppression of mixing. These patterns, verifiable via Argo floats and satellite altimetry, underscore causal roles of Coriolis effects, wind stress curl, and buoyancy forcing in shaping thermal zonation, independent of long-term trends.[65]Temporal Fluctuations and Cycles

Ocean surface temperatures exhibit diurnal fluctuations, with daytime solar heating raising sea surface temperatures (SSTs) by up to 1-2°C in low-wind conditions over the mixed layer, while nocturnal cooling restores equilibrium through longwave radiation and evaporation.[2] These short-term variations are most pronounced in calm, shallow coastal waters and diminish with depth or during stormy periods that enhance vertical mixing. Seasonal cycles dominate temporal variability in SSTs, driven primarily by latitudinal differences in insolation and the annual migration of the sun. In mid-latitudes, SST amplitudes reach 10-15°C between summer maxima and winter minima, reflecting shallow mixed layers that allow rapid response to atmospheric forcing.[66] Tropical oceans show smaller amplitudes of 1-3°C due to persistent stratification and weaker seasonal insolation contrasts.[67] Globally, the SST seasonal cycle has intensified by approximately 3.9% from 1983 to 2022, with amplified warming in northern mid-latitudes linked to reduced sea ice and altered heat fluxes.[68] On interannual timescales, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) imposes the strongest fluctuations, with El Niño events elevating equatorial Pacific SSTs by 2-3°C in the Niño 3.4 region (5°S-5°N, 120°-170°W) for 6-18 months, while La Niña phases cool the same area by similar magnitudes.[69] These anomalies propagate globally via atmospheric teleconnections, contributing up to 20-30% of year-to-year SST variance outside the Pacific.[70] ENSO's irregular cycle, averaging 2-7 years, modulates tropical cyclone activity and drought patterns through altered Walker circulation.[71] Decadal and multidecadal oscillations further structure longer-term fluctuations. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), identified in North Pacific SSTs poleward of 20°N, features warm phases enhancing Aleutian Low intensity and cool phases suppressing it, with indices fluctuating on 20-30 year timescales and amplitudes of 0.5-1°C in regional means.[72] Similarly, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) manifests as basin-wide North Atlantic SST variations of 0.4°C over 60-80 year periods, influencing Sahel rainfall and hurricane frequency.[73] However, analyses of extended instrumental records question the oscillatory nature of PDO and AMO, attributing much of their signal to stochastic variability or external forcing rather than intrinsic cycles.[74][75]Historical Records

Paleoceanographic Proxies

Paleoceanographic proxies reconstruct past ocean temperatures from geological records, including marine sediments, corals, and speleothems, extending instrumental data back millions of years. These methods rely on empirical calibrations linking geochemical or biological signals in archives to modern temperature analogs, enabling quantification of sea surface temperatures (SSTs), subsurface conditions, and deep-water masses. Proxies are categorized as inorganic (e.g., isotope and trace element ratios in carbonates) or organic (e.g., lipid biomarkers), with multiproxy syntheses used to mitigate individual uncertainties such as diagenesis, vital effects, or environmental confounders. Reconstructions reveal glacial-interglacial SST swings of 4–8°C in many basins and warmer Eocene oceans exceeding 30°C equatorially.[76][77] Oxygen isotope ratios (δ¹⁸O) in planktic and benthic foraminiferal calcite serve as a foundational proxy, where lighter δ¹⁸O incorporation increases with cooler temperatures at roughly -0.22‰ per °C due to thermodynamic fractionation. Planktic species like Globigerinoides ruber record upper ocean SSTs, while benthic forms such as Cibicides wuellerstorfi track deep-sea temperatures below 2–4°C in modern oceans. However, δ¹⁸O signals confound temperature with seawater δ¹⁸O variations from salinity gradients or global ice volume, which can amplify apparent cooling by 1–2‰ during Pleistocene glacials; paired proxies often disentangle these. This method has underpinned records spanning the Phanerozoic, though spatial biases favor low-latitude data and assume constant fractionation factors.[78][79][80] Magnesium-to-calcium ratios (Mg/Ca) in foraminiferal tests provide a complementary thermometer, as Mg substitution in calcite rises exponentially with temperature (calibrated as Mg/Ca = 0.38 exp(0.090 T) mmol/mol for some species, yielding SSTs from core-tops matching modern values within 1–2°C). This proxy isolates temperature from δ¹⁸Osw effects, facilitating ice-volume-independent deep-ocean reconstructions, such as Miocene cooling trends. Planktic Mg/Ca targets SSTs (e.g., 22–26°C in Early Cretaceous neritic settings), while benthic applications reveal bottom-water stability. Limitations include species-specific "vital effects" (±1–2°C offsets), dissolution in undersaturated waters reducing Mg/Ca by up to 10–20%, and salinity influences requiring corrections; dissolution-adjusted calibrations improve accuracy for pre-Quaternary records.[81][82][83] Organic proxies like the alkenone unsaturation index (Uᴷ'₃₇ = [C₃₇:₂]/[C₃₇:₂ + C₃₇:₃]) from haptophyte algae lipids correlate linearly with SSTs (Uᴷ'₃₇ = 0.033 T - 0.044, valid 0–30°C), preserving signals in sediments with minimal alteration. This biomarker reconstructs Quaternary SSTs aligning with foraminiferal data within 1°C and indicates polar amplification in past climates. Regional calibrations address non-temperature factors like growth season or nutrient stress, enhancing fidelity in high-latitude or upwelling zones.[84][85][86] The TEX₈₆ index, derived from glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraethers (GDGTs) of marine Thaumarchaeota, measures cyclization degrees reflecting upper-ocean temperatures (SST = 33.4 - 32.8 TEX₈₆ for global calibration, accurate to ±2–3°C in tropics). It excels in organic-rich sediments for Mesozoic–Cenozoic SSTs, capturing subsurface signals up to 200 m depth, but exhibits regional warm biases (e.g., +4–6°C in Cretaceous) and potential nutrient or oxygen influences confounding signals. Multiproxy comparisons, such as TEX₈₆ with Uᴷ'₃₇, validate records while highlighting discrepancies from export productivity or archaeal ecology.[87][88][89] Coral Sr/Ca ratios and clumped isotopes (Δ₄₇) offer high-resolution proxies for tropical SSTs over Holocene timescales, with Sr/Ca decreasing ~0.05 mmol/mol per °C and Δ₄₇ independent of δ¹⁸Osw. These extend to reef archives but are limited by upwelling or dissolution. Overall, proxy ensembles, stack-averaged for global means, indicate Phanerozoic ocean warmth exceeding modern levels by 5–10°C during greenhouse intervals, with uncertainties shrinking via Bayesian frameworks.[90][76]Instrumental Observations from 1850 Onward

Instrumental records of ocean temperature from 1850 onward rely predominantly on sea surface temperature (SST) measurements collected via ships, with subsurface data emerging later and remaining sparse until the mid-20th century. The International Comprehensive Ocean-Atmosphere Data Set (ICOADS) serves as the foundational archive, compiling over 500 million marine observations from 1662 to present, though systematic SST coverage intensifies after 1850 along major shipping lanes.[91] [92] Early SST determinations used thermometers inserted into water samples hauled aboard in canvas or wooden buckets, a method prone to underestimation due to evaporative cooling and exposure to deck air temperatures 1–2°C below the sea surface.[33] By the early 20th century, engine-room intake measurements supplemented bucket samples on steamships, reducing some biases but introducing others related to intake depth and flow dynamics.[35] Gridded SST products derived from ICOADS, such as HadSST.4 and Extended Reconstructed SST (ERSST) version 6, apply bias corrections for these historical methods, including adjustments for bucket type (canvas cooling by ~0.2–0.5°C versus wooden) and ship metadata like speed and hull material.[93] [94] HadSST.4, spanning 1850–2018, employs an ensemble approach to quantify uncertainties, revealing higher variability in pre-1900 estimates due to limited observations.[93] ERSST incorporates buoy data post-1970s and Argo floats for validation, showing closer alignment with independent profile data than earlier versions.[95] Intercomparisons indicate differences of up to 0.3°C in regional SST anomalies before 1950 between HadSST and ERSST, stemming from varying homogenization techniques and infilling of sparse grids via empirical orthogonal functions.[96] Coverage gaps persist in the Southern Hemisphere and polar regions through the 19th and early 20th centuries, with observations concentrated in the North Atlantic and Pacific trade routes, leading to extrapolated estimates with uncertainties exceeding 0.5°C in under-sampled areas.[35] Recent analyses suggest early-20th-century SSTs (1900–1930) may have been overestimated as cooler by 0.2–0.4°C in prior reconstructions due to unaccounted shifts in measurement practices during World War I.[50] Subsurface ocean temperature observations began sporadically in the late 19th century via reversing thermometers on Nansen bottles during oceanographic expeditions, but reliable profiles with near-global coverage only emerged from the late 1940s using mechanical bathythermographs (MBTs) deployed from ships.[97] These devices measured temperatures to depths of 200–300 meters, though sampling remained irregular and biased toward military routes until the 1960s. Datasets like EN4 provide subsurface profiles from 1900 onward, but pre-1950 data are limited to upper 700 meters in select basins, with quality controls addressing instrument calibration drifts of up to 0.1°C per decade.[98] Instrumental homogeneity improved post-1970 with expendable bathythermographs (XBTs), which extended profiles to 750 meters but required corrections for fall-rate errors causing depth overestimation by 1–5% in early deployments.[99] From the 1980s, moored buoys (e.g., Tropical Atmosphere Ocean array) and drifting buoys augmented ship data, enhancing spatial resolution to ~0.25°C in tropical bands by the 1990s.[94] The Argo program, deploying autonomous floats since 2000, delivers over 400,000 upper-ocean (to 2,000 meters) profiles annually, reducing uncertainties to ~0.002°C for global averages through redundant sensors and real-time quality checks.[98] Despite these advances, unresolved biases in historical adjustments—such as potential over-cooling in WWII-era engine intakes—contribute to uncertainties in decadal-scale variability, with some analyses indicating amplified trends in adjusted datasets relative to raw observations.[51] [100] Overall, instrumental records document a transition from regionally sparse SST proxies to vertically resolved, near-global monitoring, though pre-1950 data retain elevated error margins due to methodological inconsistencies.[101]Observed Trends

20th-Century Changes

Global sea surface temperatures (SST) exhibited a net warming of approximately 0.6°C over the 20th century, based on analyses of historical instrumental records compiled in datasets such as HadSST4 and NOAA's Extended Reconstructed SST (ERSST).[93][102] This estimate derives from monthly gridded anomalies relative to a 1961–1990 baseline, incorporating ship-based measurements, which dominated early records, and later buoy data.[103] The rate averaged about 0.06°C per decade from 1900 to 2000, though with significant decadal variability.[104] The warming displayed distinct phases: a pronounced increase of roughly 0.3–0.4°C from 1900 to the early 1940s, driven partly by natural variability including the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation; a subsequent period of stagnation or mild cooling (approximately -0.1°C) from the 1940s to the mid-1970s, influenced by aerosol emissions and internal ocean-atmosphere oscillations; and accelerated warming post-1975 aligning with the latter half of the century's net trend.[105][50] These patterns are evident in multiple reconstructions, though regional differences were notable, with stronger warming in the Northern Hemisphere oceans compared to the Southern. Uncertainties persist due to sparse early sampling, primarily from voluntary observing ships, and systematic biases in measurement methods, such as underestimation from uninsulated bucket thermometers leading to a cold bias of up to 0.5°C in early 20th-century estimates.[50] Correcting for such biases reduces the implied 1900–1950 warming by 20–50%, suggesting standard datasets may overestimate the century's net SST rise.[50] Subsurface ocean temperatures, inferred from later Argo floats and historical profiles, indicate heat accumulation in the upper 700 meters consistent with surface trends, though full-depth assessments for the early century remain limited.[106] These adjustments highlight challenges in attributing changes solely to external forcings amid natural variability.[107]21st-Century Accelerations and Records

Global sea surface temperatures (SST) have exhibited accelerated warming trends since the early 2000s, with peer-reviewed analyses indicating a statistically significant increase in the rate of ocean heat uptake. From 1961 to 2022, ocean warming accelerated at a rate of 0.15 ± 0.04 W m⁻² per decade, contributing to a total warming of 0.43 ± 0.08 W m⁻² over the period.[108] This acceleration is linked to rising Earth's energy imbalance, manifesting as faster multidecadal SST increases detectable in satellite and in-situ observations.[109] Since the 1990s, global ocean warming has intensified by over 25%, driven by enhanced heat accumulation in mode and intermediate waters.[110] Upper ocean heat content (OHC), a direct measure of integrated temperature changes, has risen steadily from 2000 onward, with the top 2000 meters absorbing approximately 90% of excess planetary heat. Annual OHC anomalies for 0-2000 m show consistent positive trends through 2024, surpassing prior decades in magnitude.[112] In the 2010-2019 decade, surface warming rates reached 0.280 ± 0.068°C per decade, over four times the long-term average, reflecting deeper penetration of heat into the ocean profile.[104] Record highs have been repeatedly set in the 21st century, culminating in 2023 and 2024. On August 22, 2023, global average daily SST peaked at 18.99°C (66.18°F), the highest in observational records.[113] The year 2024 marked the warmest ocean on record, with both SST and upper 2000 m OHC achieving unprecedented levels, exceeding 2023 benchmarks.[114] This 2023-2024 SST jump exceeded prior records by at least 0.25°C globally and 0.42°C in the North Atlantic, an event deemed low-probability under historical trends but consistent with ongoing heat accumulation.[115] These records align with broader surface temperature anomalies, where 2024's global ocean surface reached 1.15°C above the 20th-century average.[116]Ocean Heat Content Dynamics

Ocean heat content (OHC) quantifies the total thermal energy stored in the ocean, computed as the integral of temperature anomalies weighted by specific heat capacity, density, and volume over specified depth ranges and global extents, typically expressed in zettajoules (10^21 J).[117] This metric captures subsurface heat storage beyond surface temperatures, revealing that approximately 91% of excess energy trapped by greenhouse gases has been absorbed by the oceans since the mid-20th century.[118] Empirical estimates indicate a net OHC increase of about 436 zettajoules from 1971 to 2018, with the upper 2000 meters accounting for the majority of this accumulation due to limited deep-ocean mixing.[106] Dynamics of OHC involve surface heat fluxes from the atmosphere—primarily longwave radiation, latent, and sensible heat—followed by downward transport via turbulent diffusion, eddy mixing, and large-scale circulation patterns such as the meridional overturning circulation.[119] Ocean heat uptake efficiency, defined as the ratio of oceanic heat gain to global surface air temperature rise, has risen by roughly 20% since 1970, potentially linked to enhanced ventilation in subtropical gyres and mode water subduction.[120] Observations from the Argo float array, deployed globally since 2004, have reduced sampling uncertainties to below 0.1 W/m² for full-depth estimates, enabling detection of interannual variability tied to modes like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which modulates equatorial heat redistribution.[121] [122] Recent analyses reveal accelerations in OHC accumulation, with rates doubling from pre-1990s levels to approximately 1.0 W/m² during 2010–2022, attributed partly to internal climate modes favoring enhanced Southern Ocean uptake and reduced Atlantic export.[25] However, pre-Argo era data (before 2004) carry larger uncertainties from sparse ship-based measurements and eXpendable BathyThermograph (XBT) biases, estimated at up to 20% for upper-ocean trends, necessitating cautious attribution of long-term dynamics.[123] Full-depth OHC reached record levels in 2022, exceeding prior maxima by 14 zettajoules relative to 2021, underscoring the ocean's role as a primary heat reservoir amid ongoing energy imbalance.[124] Vertical partitioning shows ~75% of heat gain confined to the upper 700 meters, with slower penetration to abyssal layers via diapycnal mixing rates of order 10^{-5} m²/s.[125] These dynamics imply lagged feedbacks, including thermal expansion contributing ~30% to global sea-level rise since 1993.[118]Driving Mechanisms

Natural Forcings and Internal Variability

Natural forcings influencing ocean temperatures include variations in solar irradiance, volcanic aerosol injections, and long-term orbital parameters known as Milankovitch cycles. Solar variability, such as the 11-year sunspot cycle, modulates incoming solar radiation by approximately 0.1% globally, leading to small but detectable sea surface temperature (SST) responses of about 0.1–0.2°C in the tropical Pacific over decadal scales.[126] Volcanic eruptions, particularly large stratospheric events like the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption, inject sulfate aerosols that reflect sunlight, causing global SST cooling of 0.2–0.5°C for 1–3 years post-eruption by reducing surface insolation and enhancing ocean heat uptake.[127] [128] Increased volcanic activity from 2003–2012, including eruptions like El Chichón (1982) and others, contributed to a temporary reduction in the global warming trend by approximately 0.08°C over that decade through aerosol-induced radiative forcing.[127] Milankovitch cycles—eccentricity (100,000-year period), obliquity (41,000 years), and precession (23,000 years)—alter seasonal insolation distribution by up to 25% at high latitudes, driving long-term ocean temperature oscillations tied to glacial-interglacial transitions, with evidence from deep-sea sediment proxies showing amplified deep-ocean warming during interglacials.[129] [130] Internal variability arises from chaotic interactions within the climate system, producing quasi-oscillatory patterns in ocean temperatures without external forcing. The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), with a 2–7 year periodicity, features SST anomalies exceeding 1°C in the equatorial Pacific, where El Niño phases warm global averages by 0.1–0.2°C temporarily via altered atmospheric circulation and heat redistribution.[131] The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), operating on 20–30 year timescales, manifests as ENSO-like SST patterns north of 20°N, with cool phases enhancing Aleutian Low intensity and contributing to multidecadal cooling in the North Pacific SST by up to 0.5°C.[132] [72] Similarly, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) drives North Atlantic SST fluctuations of 0.4–0.5°C over 60–80 years, linked to thermohaline circulation variations, influencing hemispheric temperature variance and masking forced trends.[133] These modes interact; for instance, PDO and AMO phases can modulate ENSO amplitude, amplifying internal variability's role in regional ocean heat content changes by 20–50% on decadal scales.[134] [135] Attribution studies indicate that while natural forcings dominate paleoclimate variability, internal modes explain much of the interannual-to-decadal fluctuations in modern instrumental records, complicating signal detection amid low-frequency trends.[136] For example, a shift to positive PDO and AMO phases in the mid-20th century contributed to accelerated North Pacific and Atlantic warming, independent of radiative changes.[137] Ocean circulation, such as Rossby wave propagation, further propagates these variabilities, with models showing internal ocean dynamics accounting for up to 30% of upper-ocean temperature variance in the extratropics.[138]Anthropogenic Contributions

Human emissions of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide from fossil fuel combustion, cement production, and land-use changes, have elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations from approximately 280 ppm in the pre-industrial era to over 420 ppm by 2023, enhancing the greenhouse effect and creating a top-of-atmosphere radiative imbalance of about 0.9 W/m². This excess energy, equivalent to roughly 436 zettajoules absorbed by the oceans in the upper 2000 meters from 1971 to 2010, drives ocean warming as the ocean takes up over 90% of the anthropogenic heat excess in the Earth system, buffering atmospheric temperature rise.[139][140][118] Attribution analyses, employing detection and attribution techniques that compare observed ocean heat content trends with climate model simulations under anthropogenic and natural forcings, indicate that the post-1950s warming in the global ocean, particularly the subsurface layers, is inconsistent with internal variability or natural drivers like solar irradiance and volcanic aerosols alone. For instance, the observed increase in ocean heat content since the 1970s aligns closely with model projections forced by rising greenhouse gas concentrations, with the anthropogenic signal emerging robustly by the late 20th century.[141][140][25] Other anthropogenic factors, such as tropospheric aerosols from industrial emissions exerting a cooling influence via scattering and cloud brightening, have partially offset greenhouse gas warming until recent decades when aerosol regulations reduced their net effect, allowing accelerated ocean heat uptake. However, the dominant driver remains the long-lived greenhouse gases, with their radiative forcing exceeding that of short-lived pollutants. Peer-reviewed studies confirm that without human emissions, recent marine heatwaves and sustained sea surface temperature rises, such as those exceeding 1°C in parts of the tropical oceans since 1900, would be virtually impossible under natural conditions alone.[139][142][143]Challenges in Causal Attribution

Attributing observed changes in ocean temperature to specific causes, particularly anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions versus natural variability, faces significant methodological hurdles due to the complexity of ocean-atmosphere interactions and limitations in observational data. Causal attribution typically relies on detection and attribution (D&A) frameworks, which compare observed trends against model simulations of natural-only forcings (e.g., solar irradiance, volcanic aerosols) and all-forcings scenarios including anthropogenic factors. However, these approaches struggle to disentangle signals because natural internal variability, such as the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) or Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), operates on decadal to multidecadal timescales that overlap with anthropogenic warming trends, potentially amplifying or masking forced responses. For instance, multidecadal variations in global surface temperature and ocean surface temperature since 1866 are largely attributable to anthropogenic forcing in some analyses, yet interannual and decadal fluctuations remain dominated by natural modes, complicating precise quantification.[144][138] A primary challenge stems from uncertainties in historical ocean heat content (OHC) measurements, which underpin much of the attribution evidence. Pre-2005 data, before the widespread deployment of the ARGO float array, depend on sparse ship-based and moored observations, leading to potential biases in vertical and spatial sampling; for example, global OHC showed no robust trend from 1960 to 1990 due to deep ocean cooling offsetting minor upper-ocean gains, a pattern not fully captured in early reconstructions. Modern estimates indicate the ocean absorbs about 90-91% of excess heat from greenhouse gases, but sensitivity analyses reveal that choices in bias corrections, instrumental errors, and mapping methods can alter decadal OHC trends by factors of 2-3, with upper-ocean (0-700 m) uncertainties exceeding 20% in some periods. These gaps hinder confident separation of radiative forcing effects from unforced variability, as internal ocean modes like meridional overturning circulation can redistribute heat without net surface warming.[145][118][146] Climate models introduce further attribution difficulties, as they often underestimate observed internal variability or fail to reproduce spatial patterns of warming. Anthropogenic forcing is expected to produce relatively uniform heat uptake, yet post-2005 OHC increases have concentrated in mid-latitude bands near 40°N and 40°S with minimal tropical or deep-ocean penetration, a fingerprint more aligned with natural circulation shifts than pure radiative imbalance in some critiques. Detection methods assume model fidelity in simulating counterfactual worlds, but discrepancies—such as early-20th-century cold biases in sea surface temperatures unexplainable by internal variability alone—suggest models may overestimate anthropogenic signals by underweighting unforced land-ocean contrasts. Moreover, attribution of recent accelerations (e.g., post-2010) to reduced aerosol cooling versus emerging natural cycles like a potential AMO downturn remains unresolved, as ensemble simulations exhibit wide spread in projected ocean responses.[147][50][148] Empirical challenges also arise from confounding factors like volcanic influences and solar cycles, which can induce transient cooling or warming that mimics long-term trends; for example, the 1960-1990 OHC stasis aligns with post-eruption deep cooling rather than a pure anthropogenic pause. Peer-reviewed critiques highlight that while fingerprinting techniques attribute over 70-90% of post-1950 OHC rise to human forcings in optimized models, alternative reconstructions emphasizing natural decadal rivals question dominance claims, especially regionally. These issues underscore the need for improved observing systems and hybrid statistical-dynamical methods to enhance causal realism, as over-reliance on model-dependent attribution risks conflating correlation with causation amid persistent data voids in the deep ocean (>2000 m), where heat storage uncertainties exceed 50%.[145][149][144]Impacts and Consequences

Physical and Dynamical Effects

Ocean warming induces thermal expansion of seawater, contributing significantly to global mean sea level rise. Since the 1970s, thermal expansion has accounted for about 30-50% of observed sea level rise, with estimates indicating it comprised 56% in recent decades as ocean heat content increased.[150] This effect arises from the volumetric expansion of water as it absorbs excess heat, primarily in the upper ocean layers, exacerbating coastal inundation and erosion risks.[151] Increased ocean temperatures enhance upper-ocean stratification by warming surface waters and reducing their density relative to deeper layers, which suppresses vertical mixing and nutrient entrainment from below.[152] Observations show summertime increases in pycnocline stratification and shallower mixed-layer depths, particularly in subtropical regions, limiting heat transfer to deeper oceans and amplifying surface warming feedbacks.[153] This stratification intensifies since the mid-20th century, as the ocean has absorbed over 90% of anthropogenic excess heat, altering the density gradient and potentially reducing the efficiency of mode water formation.[154] Warmer temperatures disrupt large-scale ocean circulation patterns, including the thermohaline circulation, by freshening and warming high-latitude surface waters, which stabilizes the water column and weakens overturning.[155] Recent accelerations in ocean heat uptake, nearly doubling since the 1990s, have concentrated warming in mid-latitude bands around 40°N and 40°S, influencing gyre dynamics and meridional heat transport.[25] In eastern boundary upwelling systems, warming may intensify stratification, shoal upwelling fronts, and alter source water depths, potentially reducing nutrient supply despite stronger winds.[156][157] These dynamical shifts contribute to regional anomalies, such as delayed upwelling onset in systems like the California Current, where increased stratification traps heat near the surface and modifies cross-shelf exchanges.[158] Overall, ocean heat accumulation since 2005 has focused in specific latitudinal bands with minimal net warming in equatorial zones, reflecting interplay between advection, diffusion, and wind-driven dynamics.[147] Such changes pose challenges for predicting circulation stability, as enhanced hydrological cycles from warming further promote stratification and modulate heat uptake efficiency.[159]Ecological and Biological Responses