Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

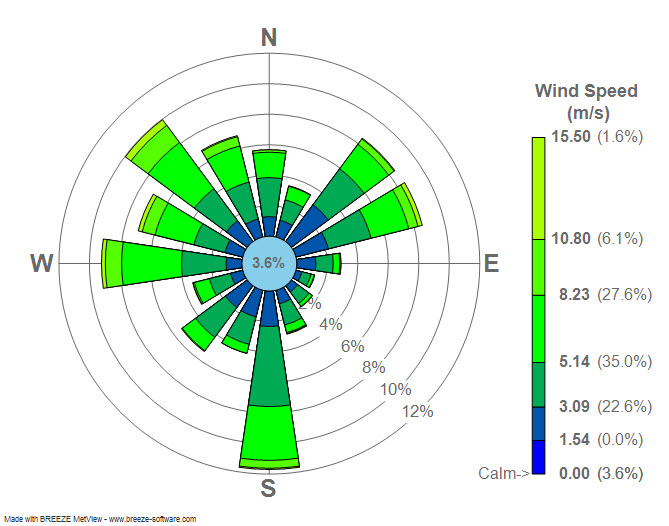

Wind rose

View on Wikipedia

A wind rose is a diagram used by meteorologists to give a succinct view of how wind speed and direction are typically distributed at a particular location. Historically, wind roses were predecessors of the compass rose (also known as a wind rose), found on nautical charts, as there was no differentiation between a cardinal direction and the wind which blew from such a direction. Using a polar coordinate system of gridding, the frequency of winds over a time period is plotted by wind direction, with colour bands showing wind speed ranges. The direction of the longest spoke shows the wind direction with the greatest frequency, the prevailing wind.

History

[edit]

The Tower of the Winds in Athens, of about 50 BC is in effect a physical wind rose, as an octagonal tower with eight large reliefs of the winds near the top. It was designed by Andronicus of Cyrrhus, who seems to have written a book on the winds. A passage in Vitruvius's chapter on town planning in his On Architecture (De architectura) seems to be based on this missing book. The emphasis is on planning street orientations to maximize the benefits, and minimize the harms, from the various winds. The London Vitruvius, the oldest surviving manuscript, includes only one of the original illustrations, a rather crudely drawn wind rose in the margin. This was written in Germany in about 800 to 825, probably at the abbey of Saint Pantaleon, Cologne.[1]

Before the development of the compass rose, a wind rose was included on maps in order to let the reader know which directions the 8 major winds (and sometimes 8 half-winds and 16 quarter-winds) blew within the plan view. No differentiation was made between cardinal directions and the winds which blew from those directions. North was depicted with a fleur de lis, while east was shown as a Christian cross to indicate the direction of Jerusalem from Europe.[2][3]

Use

[edit]Presented in a circular format, the modern wind rose shows the frequency of winds blowing from particular directions over a specified period. The length of each "spoke" around the circle is related to the frequency that the wind blows from a particular direction per unit time. Each concentric circle represents a different frequency, emanating from zero at the center to increasing frequencies at the outer circles. A wind rose plot may contain additional information, in that each spoke is broken down into colour-coded bands that show wind speed ranges. Wind roses typically use 16 cardinal directions, such as north (N), NNE, NE, etc., although they may be subdivided into as many as 32 directions.[4][5] In terms of angle measurement in degrees, North corresponds to 0°/360°, East to 90°, South to 180° and West to 270°.

Compiling a wind rose is one of the preliminary steps taken in constructing airport runways, as aircraft can have a lower ground speed at both landing and takeoff when pointing against the wind.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Detailed record for Harley 2767 Archived 2018-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, British Library

- ^ Dan Reboussin (2005)Wind Rose. Archived 2016-09-01 at the Wayback Machine University of Florida. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Thoen, Bill. "Origins of the Compass Rose". GISNet. Archived from the original on 2022-06-05. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

- ^ Jan Curtis (2007). Wind Rose Data. Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ Wind Rose Data by folders by States, to sub-folders by cities Retrieved on 2022-09-03.

External links

[edit]- Wind Rose Data for the U.S. (Interactive version)

- "Carrie Bow Cay - Wind Rose". January 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09.

- "Make wind rose diagrams on line". www.windrose.xyz. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 22 Oct 2020.