Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Computer worm

View on Wikipedia

A computer worm is a standalone malware computer program that replicates itself in order to spread to other computers.[1] It often uses a computer network to spread itself, relying on security failures on the target computer to access it. It will use this machine as a host to scan and infect other computers. When these new worm-invaded computers are controlled, the worm will continue to scan and infect other computers using these computers as hosts, and this behavior will continue.[2] Computer worms use recursive methods to copy themselves without host programs and distribute themselves based on exploiting the advantages of exponential growth, thus controlling and infecting more and more computers in a short time.[3] Worms almost always cause at least some harm to the network, even if only by consuming bandwidth, whereas viruses almost always corrupt or modify files on a targeted computer.

Many worms are designed only to spread, and do not attempt to change the systems they pass through. However, as the Morris worm and Mydoom showed, even these "payload-free" worms can cause major disruption by increasing network traffic and other unintended effects.

History

[edit]The first ever computer worm is generally accepted to be a self-replicating version of Creeper created by Ray Tomlinson and Bob Thomas at BBN in 1971 to replicate itself across the ARPANET.[4][5] Tomlinson also devised the first antivirus software, named Reaper, to delete the Creeper program.

The term "worm" was first used in this sense in John Brunner's 1975 novel, The Shockwave Rider. In the novel, Nichlas Haflinger designs and sets off a data-gathering worm in an act of revenge against the powerful people who run a national electronic information web that induces mass conformity. "You have the biggest-ever worm loose in the net, and it automatically sabotages any attempt to monitor it. There's never been a worm with that tough a head or that long a tail!"[6] "Then the answer dawned on him, and he almost laughed. Fluckner had resorted to one of the oldest tricks in the store and turned loose in the continental net a self-perpetuating tapeworm, probably headed by a denunciation group "borrowed" from a major corporation, which would shunt itself from one nexus to another every time his credit-code was punched into a keyboard. It could take days to kill a worm like that, and sometimes weeks."[6]

Xerox PARC was studying the use of "worm" programs for distributed computing in 1979.[7]

On November 2, 1988, Robert Tappan Morris, a Cornell University computer science graduate student, unleashed what became known as the Morris worm, disrupting many computers then on the Internet, guessed at the time to be one tenth of all those connected.[8] During the Morris appeal process, the U.S. Court of Appeals estimated the cost of removing the worm from each installation at between $200 and $53,000; this work prompted the formation of the CERT Coordination Center[9] and Phage mailing list.[10] Morris himself became the first person tried and convicted under the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.[11]

Conficker, a computer worm discovered in 2008 that primarily targeted Microsoft Windows operating systems, is a worm that employs three different spreading strategies: local probing, neighborhood probing, and global probing.[12] This worm was considered a hybrid epidemic and affected millions of computers. The term "hybrid epidemic" is used because of the three separate methods it employed to spread, which was discovered through code analysis.[13]

Features

[edit]Independence

Computer viruses generally require a host program.[14] The virus writes its own code into the host program. When the program runs, the written virus program is executed first, causing infection and damage. A worm does not need a host program, as it is an independent program or code chunk. Therefore, it is not restricted by the host program, but can run independently and actively carry out attacks.[15][16]

Exploit attacks

Because a worm is not limited by the host program, worms can take advantage of various operating system vulnerabilities to carry out active attacks. For example, the "Nimda" virus exploits vulnerabilities to attack.

Complexity

Some worms are combined with web page scripts, and are hidden in HTML pages using VBScript, ActiveX and other technologies. When a user accesses a webpage containing a virus, the virus automatically resides in memory and waits to be triggered. There are also some worms that are combined with backdoor programs or Trojan horses, such as "Code Red".[17]

Contagiousness

Worms are more infectious than traditional viruses. They not only infect local computers, but also all servers and clients on the network based on the local computer. Worms can easily spread through shared folders, e-mails,[18] malicious web pages, and servers with a large number of vulnerabilities in the network.[19]

Harm

[edit]Any code designed to do more than spread the worm is typically referred to as the "payload". Typical malicious payloads might delete files on a host system (e.g., the ExploreZip worm), encrypt files in a ransomware attack (e.g., the WannaCry worm), or exfiltrate data such as confidential documents or passwords.[20]

Some worms may install a backdoor. This allows the computer to be remotely controlled by the worm author as a "zombie". Networks of such machines are often referred to as botnets and are very commonly used for a range of malicious purposes, including sending spam or performing DoS attacks.[21][22][23]

Some special worms attack industrial systems in a targeted manner. Stuxnet was primarily transmitted through LANs and infected thumb-drives, as its targets were never connected to untrusted networks, like the internet. This virus can destroy the core production control computer software used by chemical, power generation and power transmission companies in various countries around the world - in Stuxnet's case, Iran, Indonesia and India were hardest hit - it was used to "issue orders" to other equipment in the factory, and to hide those commands from being detected. Stuxnet used multiple vulnerabilities and four different zero-day exploits (e.g.: [1]) in Windows systems and Siemens SIMATICWinCC systems to attack the embedded programmable logic controllers of industrial machines. Although these systems operate independently from the network, if the operator inserts a virus-infected drive into the system's USB interface, the virus will be able to gain control of the system without any other operational requirements or prompts.[24][25][26]

Countermeasures

[edit]Worms spread by exploiting vulnerabilities in operating systems. Vendors with security problems supply regular security updates[27] (see "Patch Tuesday"), and if these are installed to a machine, then the majority of worms are unable to spread to it. If a vulnerability is disclosed before the security patch released by the vendor, a zero-day attack is possible.

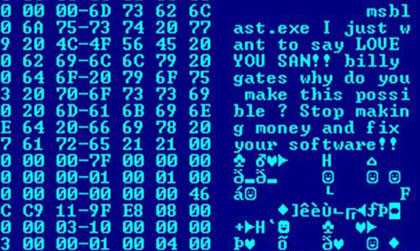

Users need to be wary of opening unexpected emails,[28][29] and should not run attached files or programs, or visit web sites that are linked to such emails. However, as with the ILOVEYOU worm, and with the increased growth and efficiency of phishing attacks, it remains possible to trick the end-user into running malicious code.

Anti-virus and anti-spyware software are helpful, but must be kept up-to-date with new pattern files at least every few days. The use of a firewall is also recommended.

Users can minimize the threat posed by worms by keeping their computers' operating system and other software up to date, avoiding opening unrecognized or unexpected emails and running firewall and antivirus software.[30]

Mitigation techniques include:

- ACLs in routers and switches

- Packet-filters

- TCP Wrapper/ACL enabled network service daemons

- EPP/EDR software

- Nullroute

Infections can sometimes be detected by their behavior - typically scanning the Internet randomly, looking for vulnerable hosts to infect.[31][32] In addition, machine learning techniques can be used to detect new worms, by analyzing the behavior of the suspected computer.[33]

Helpful worms

[edit]A helpful worm or anti-worm is a worm designed to do something that its author feels is helpful, though not necessarily with the permission of the executing computer's owner. Beginning with the first research into worms at Xerox PARC, there have been attempts to create useful worms. Those worms allowed John Shoch and Jon Hupp to test the Ethernet principles on their network of Xerox Alto computers.[34] Similarly, the Nachi family of worms tried to download and install patches from Microsoft's website to fix vulnerabilities in the host system by exploiting those same vulnerabilities.[35] In practice, although this may have made these systems more secure, it generated considerable network traffic, rebooted the machine in the course of patching it, and did its work without the consent of the computer's owner or user. Another example of this approach is Roku OS patching a bug allowing for Roku OS to be rooted via an update to their screensaver channels, which the screensaver would attempt to connect to the telnet and patch the device.[36] Regardless of their payload or their writers' intentions, security experts regard all worms as malware.

One study proposed the first computer worm that operates on the second layer of the OSI model (Data link Layer), utilizing topology information such as Content-addressable memory (CAM) tables and Spanning Tree information stored in switches to propagate and probe for vulnerable nodes until the enterprise network is covered.[37]

Anti-worms have been used to combat the effects of the Code Red,[38] Blaster, and Santy worms. Welchia is an example of a helpful worm.[39] Utilizing the same deficiencies exploited by the Blaster worm, Welchia infected computers and automatically began downloading Microsoft security updates for Windows without the users' consent. Welchia automatically reboots the computers it infects after installing the updates. One of these updates was the patch that fixed the exploit.[39]

Other examples of helpful worms are "Den_Zuko", "Cheeze", "CodeGreen", and "Millenium".[39]

Art worms support artists in the performance of massive scale ephemeral artworks. It turns the infected computers into nodes that contribute to the artwork.[40]

See also

[edit]- List of computer worms

- BlueKeep

- Botnet

- Code Shikara (Worm)

- Computer and network surveillance

- Computer virus

- Computer security

- Email spam

- Father Christmas (computer worm)

- Self-replicating machine

- Technical support scam – unsolicited phone calls from a fake "tech support" person, claiming that the computer has a virus or other problems

- Timeline of computer viruses and worms

- Trojan horse (computing)

- Worm memory test

- XSS worm

- Zombie (computer science)

References

[edit]- ^ Barwise, Mike. "What is an internet worm?". BBC. Archived from the original on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 9 September 2010.

- ^ Zhang, Changwang; Zhou, Shi; Chain, Benjamin M. (2015-05-15). "Hybrid Epidemics—A Case Study on Computer Worm Conficker". PLOS ONE. 10 (5) e0127478. arXiv:1406.6046. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027478Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127478. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4433115. PMID 25978309.

- ^ Marion, Jean-Yves (2012-07-28). "From Turing machines to computer viruses". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 370 (1971): 3319–3339. Bibcode:2012RSPTA.370.3319M. doi:10.1098/rsta.2011.0332. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 22711861.

- ^ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. Vol. 27–28. IEEE Computer Society. 2005. p. 74.

[...]from one machine to another led to experimentation with the Creeper program, which became the world's first computer virus: a computation that used the network to recreate itself on another node, and spread from node to node. The source code of creeper remains unknown.

- ^ From the first email to the first YouTube video: a definitive internet history. Tom Meltzer and Sarah Phillips. The Guardian. 23 October 2009

- ^ a b Brunner, John (1975). The Shockwave Rider. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-06-010559-4.

- ^ J. Postel (17 May 1979). Internet Meeting Notes 8, 9, 10 & 11 May 1979. p. 5. doi:10.17487/RFC2555. RFC 2555.

- ^ "The Submarine". www.paulgraham.com.

- ^ "Security of the Internet". CERT/CC. Archived from the original on 1998-04-15. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ "Phage mailing list". securitydigest.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2014-09-17.

- ^ Dressler, J. (2007). "United States v. Morris". Cases and Materials on Criminal Law. St. Paul, MN: Thomson/West. ISBN 978-0-314-17719-3.

- ^ Zhang, Changwang; Zhou, Shi; Chain, Benjamin M. (2015-05-15). "Hybrid Epidemics—A Case Study on Computer Worm Conficker". PLOS ONE. 10 (5) e0127478. arXiv:1406.6046. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027478Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127478. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4433115. PMID 25978309.

- ^ Zhang, Changwang; Zhou, Shi; Chain, Benjamin M. (2015-05-15). Sun, Gui-Quan (ed.). "Hybrid Epidemics—A Case Study on Computer Worm Conficker". PLOS ONE. 10 (5) e0127478. arXiv:1406.6046. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027478Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127478. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4433115. PMID 25978309.

- ^ "Worm vs. Virus: What's the Difference and Does It Matter?". Worm vs. Virus: What's the Difference and Does It Matter?. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ Yeo, Sang-Soo. (2012). Computer science and its applications: CSA 2012, Jeju, Korea, 22-25.11.2012. Springer. p. 515. ISBN 978-94-007-5699-1. OCLC 897634290.

- ^ Yu, Wei; Zhang, Nan; Fu, Xinwen; Zhao, Wei (October 2010). "Self-Disciplinary Worms and Countermeasures: Modeling and Analysis". IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems. 21 (10): 1501–1514. Bibcode:2010ITPDS..21.1501Y. doi:10.1109/tpds.2009.161. ISSN 1045-9219. S2CID 2242419.

- ^ Brooks, David R. (2017), "Introducing HTML", Programming in HTML and PHP, Undergraduate Topics in Computer Science, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–10, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-56973-4_1, ISBN 978-3-319-56972-7

- ^ Deng, Yue; Pei, Yongzhen; Li, Changguo (2021-11-09). "Parameter estimation of a susceptible–infected–recovered–dead computer worm model". Simulation. 98 (3): 209–220. doi:10.1177/00375497211009576. ISSN 0037-5497. S2CID 243976629.

- ^ Lawton, George (June 2009). "On the Trail of the Conficker Worm". Computer. 42 (6): 19–22. Bibcode:2009Compr..42f..19L. doi:10.1109/mc.2009.198. ISSN 0018-9162. S2CID 15572850.

- ^ "What is a malicious payload?". www.cloudflare.com. Retrieved 2025-01-02.

- ^ Ray, Tiernan (February 18, 2004). "Business & Technology: E-mail viruses blamed as spam rises sharply". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ McWilliams, Brian (October 9, 2003). "Cloaking Device Made for Spammers". Wired.

- ^ "Hacker threats to bookies probed". BBC News. February 23, 2004.

- ^ Bronk, Christopher; Tikk-Ringas, Eneken (May 2013). "The Cyber Attack on Saudi Aramco". Survival. 55 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1080/00396338.2013.784468. ISSN 0039-6338. S2CID 154754335.

- ^ Lindsay, Jon R. (July 2013). "Stuxnet and the Limits of Cyber Warfare". Security Studies. 22 (3): 365–404. doi:10.1080/09636412.2013.816122. ISSN 0963-6412. S2CID 154019562.

- ^ Wang, Guangwei; Pan, Hong; Fan, Mingyu (2014). "Dynamic Analysis of a Suspected Stuxnet Malicious Code". Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Science and Service System. Vol. 109. Paris, France: Atlantis Press. doi:10.2991/csss-14.2014.86. ISBN 978-94-6252-012-7.

- ^ "USN list". Ubuntu. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ "Threat Description Email-Worm". Archived from the original on 2018-01-16. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- ^ "Email-Worm:VBS/LoveLetter Description | F-Secure Labs". www.f-secure.com.

- ^ "Computer Worm Information and Removal Steps". Veracode. 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

- ^ Sellke, S. H.; Shroff, N. B.; Bagchi, S. (2008). "Modeling and Automated Containment of Worms". IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing. 5 (2): 71–86. Bibcode:2008ITDSC...5...71S. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2007.70230.

- ^ "A New Way to Protect Computer Networks from Internet Worms". Newswise. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- ^ Moskovitch, Robert; Elovici, Yuval; Rokach, Lior (2008). "Detection of unknown computer worms based on behavioral classification of the host". Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 52 (9): 4544–4566. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2008.01.028. S2CID 1097834.

- ^ Shoch, John; Hupp, Jon (Mar 1982). "The "Worm" Programs - Early Experience with a Distributed Computation". Communications of the ACM. 25 (3): 172–180. doi:10.1145/358453.358455. S2CID 1639205.

- ^ "Virus alert about the Nachi worm". Microsoft.

- ^ "Root My Roku". GitHub.

- ^ Al-Salloum, Z. S.; Wolthusen, S. D. (2010). "A link-layer-based self-replicating vulnerability discovery agent". The IEEE symposium on Computers and Communications. p. 704. doi:10.1109/ISCC.2010.5546723. ISBN 978-1-4244-7754-8. S2CID 3260588.

- ^ "vnunet.com 'Anti-worms' fight off Code Red threat". Sep 14, 2001. Archived from the original on 2001-09-14.

- ^ a b c The Welchia Worm. December 18, 2003. p. 1. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Aycock, John (2022-09-15). "Painting the Internet". Leonardo. 42 (2): 112–113 – via MUSE.

External links

[edit]- Malware Guide (archived link) – Guide for understanding, removing and preventing worm infections on Vernalex.com.

- "The 'Worm' Programs – Early Experience with a Distributed Computation", John Shoch and Jon Hupp, Communications of the ACM, Volume 25 Issue 3 (March 1982), pp. 172–180.

- "The Case for Using Layered Defenses to Stop Worms", Unclassified report from the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), 18 June 2004.

- Worm Evolution (archived link), paper by Jago Maniscalchi on Digital Threat, 31 May 2009.

- Comprehensive Study on Computer Worm, Valliammal.N

- How to remove a Computer worm

- The Morris Worm

Computer worm

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Definition

A computer worm is a standalone malware program that self-replicates to propagate across computer networks without requiring attachment to a host file or user intervention.[1][9] Unlike viruses, which depend on infecting executable files or documents, worms operate independently, exploiting vulnerabilities in operating systems, network services, or protocols to scan for and infect susceptible systems.[10] This autonomy enables rapid dissemination, as the worm generates copies of itself and transmits them to new targets, often consuming bandwidth and computational resources in the process.[11] Key characteristics include self-contained code that executes directly upon infection, network-oriented propagation methods such as email attachments, peer-to-peer sharing, or direct vulnerability exploitation (e.g., buffer overflows in services like SMB), and potential payloads that may delete files, install backdoors, or launch denial-of-service attacks.[12] Worms do not alter host files for replication but may modify system configurations to facilitate further spread, such as opening backdoor ports or disabling security features.[13] Their design prioritizes evasion and persistence, often incorporating polymorphic techniques to mutate code and avoid detection by signature-based antivirus tools.[14] Empirical evidence from incidents demonstrates worms' capacity for widespread disruption; for instance, they leverage unpatched software flaws to achieve exponential growth, with replication rates determined by network topology and vulnerability prevalence rather than human behavior.[15] This distinguishes them causally as network-centric threats, where propagation velocity correlates directly with exploitable surface area in interconnected systems.[11]Distinctions from Related Malware

A computer worm differs from other malware primarily in its standalone nature and autonomous propagation: it is a self-contained program that replicates and spreads across networks without attaching to a host file or requiring user intervention, exploiting vulnerabilities to infect remote systems directly.[1] In contrast, a virus requires integration with a legitimate host program or file, such as an executable or document, and spreads only when the infected host is executed by a user, often via email attachments or shared media.[16] [17] This host dependency limits viruses to slower, user-mediated dissemination, whereas worms achieve rapid, exponential spread independent of human action, as seen in their exploitation of network services like email servers or RPC vulnerabilities.[11] Trojans, by definition, do not self-replicate; they disguise themselves as benign software to trick users into installation, relying entirely on social engineering for initial infection and lacking any inherent propagation mechanism beyond the payload's potential to download additional components.[18] Unlike worms, which prioritize replication to maximize reach, trojans focus on deception for persistence on a single system, such as granting backdoor access, without autonomously seeking new hosts.[17] Other related malware exhibit further distinctions: rootkits emphasize concealment by modifying operating system components to hide activities, but they neither replicate nor propagate independently, often serving as enablers for worms or trojans rather than standalone spreaders.[19] Ransomware, while capable of self-propagation if worm-like traits are incorporated (e.g., WannaCry's 2017 exploitation of EternalBlue), is classified by its extortion payload—encrypting files for monetary demands—rather than replication as a core trait, with many variants spreading via phishing rather than network autonomy.[20] Bots, which assemble infected machines into command-and-control networks, frequently result from worm infections but derive their identity from coordinated post-infection behavior, not the initial self-replicating spread.[21]| Malware Type | Host Dependency | Replication Mechanism | Primary Propagation Method | Example Impact Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worm | None (standalone) | Self-contained code duplicates full instances | Network exploits (e.g., buffer overflows, weak auth) without user action | Resource exhaustion, backdoor installation via mass infection[1][11] |

| Virus | Requires attachment to host file/program | Modifies host to insert viral code | User-executed hosts (e.g., opening infected files) | Corruption of files/systems upon host activation[16][17] |

| Trojan | None, but mimics legit software | No inherent replication | User download/execution via deception | Stealthy access, data theft without spread[18] |

| Rootkit | Often embeds in kernel/OS | Minimal or none; focuses on hiding | Manual installation or bundled with other malware | Evasion of detection, enabling persistence[19] |

Historical Development

Origins in Early Computing

The theoretical foundations for self-replicating programs, akin to computer worms, trace back to mathematician John von Neumann's work on self-reproducing automata. In a series of lectures delivered between 1948 and 1953 at the University of Illinois, von Neumann explored mathematical models of cellular automata capable of universal construction and replication, drawing analogies to biological reproduction.[24] These ideas, compiled and published posthumously in 1966 as Theory of Self-Reproducing Automata, provided the conceptual basis for programs that could autonomously copy and propagate themselves, though no practical digital implementations followed immediately due to hardware limitations of the era.[25] The first experimental realization of such a program emerged in 1971 with Creeper, developed by engineer Bob Thomas at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) Technologies. Written for the TENEX operating system on ARPANET—the U.S. Department of Defense's precursor to the modern internet—Creeper was an innocuous test to demonstrate a program's ability to traverse networked computers.[26] Initially, it moved from machine to machine, displaying the message "I'm the creeper, catch me if you can!" on infected terminals, without altering files or causing harm.[27] A subsequent enhancement by BBN colleague Ray Tomlinson enabled Creeper to copy itself rather than merely relocate, marking the first instance of true self-replication across a network of about 20-30 DEC PDP-10 systems.[28] In response, Tomlinson created Reaper, a companion program deployed the same year to seek out and delete Creeper instances. Like Creeper, Reaper replicated across ARPANET to ensure comprehensive removal, functioning as an early form of automated countermeasure without user intervention on each host.[29] These experiments highlighted the feasibility of autonomous propagation in distributed systems but remained confined to controlled research environments, with no malicious intent or widespread disruption reported.[30] No prior practical worms are documented in pre-1971 computing, as isolated mainframes lacked the networked infrastructure for replication.[27]Proliferation in the Internet Era (1980s-2000s)

The proliferation of computer worms accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s as the ARPANET evolved into the broader Internet, enabling rapid self-replication across interconnected networks. Early instances exploited nascent vulnerabilities in Unix-based systems, marking a shift from isolated experiments to widespread disruptions. The Morris worm, released on November 2, 1988, by Cornell graduate student Robert Tappan Morris, became the first to achieve significant scale, infecting approximately 6,000 machines—about 10% of the Internet's estimated hosts at the time—primarily through buffer overflow exploits in services like fingerd and sendmail.[4][31] This event caused widespread slowdowns and crashes due to resource exhaustion, rather than direct payload damage, and prompted the creation of the first Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) at Carnegie Mellon University.[32] During the 1990s, worm activity remained sporadic amid growing but still limited Internet adoption, with most threats manifesting as hybrid malware or viruses rather than pure autonomous worms. The decade saw increased awareness post-Morris, yet vulnerabilities persisted, setting the stage for exponential growth in the early 2000s as email became ubiquitous and Windows systems dominated consumer computing. The ILOVEYOU worm, unleashed on May 4, 2000, exemplified this escalation by spreading via mass-mailed Visual Basic Script attachments disguised as love letters, infecting over 45 million computers in 24 hours and affecting roughly 10% of Internet-connected devices globally.[33][34] It overwrote critical files, stole passwords, and caused an estimated $10 billion in cleanup and lost productivity costs, primarily targeting Windows 95/98/NT systems.[35] Network-targeted worms further intensified proliferation by exploiting server-side flaws without user interaction. Code Red, detected on July 15, 2001, leveraged a buffer overflow in Microsoft IIS web servers, infecting over 359,000 hosts in under 14 hours through random scanning for vulnerable systems.[36] Its payload defaced websites with "Hacked by Chinese!" messages and launched denial-of-service attacks against targets like the White House IP, generating $2.6 billion in global damages before self-terminating on August 20, 2001.[37] Similarly, the Blaster worm, activated on August 11, 2003, propagated via the DCOM RPC vulnerability in unpatched Windows 2000/XP systems, infecting at least 100,000 machines and peaking at millions of attempts per day by August 16.[38][39] Blaster's payload triggered system reboots and DDoS floods against a Microsoft update server, incurring millions in remediation costs and underscoring the risks of delayed patching in an increasingly broadband-enabled era.[40] These incidents highlighted causal factors in worm proliferation: unpatched software vulnerabilities, uniform operating system adoption, and scalable propagation vectors like email and port scanning, which allowed exponential spread modeled by epidemiological SIR dynamics.[41] By the mid-2000s, such worms had infected tens of millions of devices, disrupted critical infrastructure, and catalyzed institutional responses, including mandatory vulnerability disclosures and coordinated takedowns, though source code availability often enabled variants.[42] Empirical data from these events revealed infection rates doubling every few hours in susceptible populations, with total damages exceeding tens of billions cumulatively, driven by indirect effects like network congestion over direct destruction.[43]Contemporary Worms and Variants (2010s-2025)

Stuxnet, discovered in June 2010, represented a paradigm shift in worm sophistication, targeting supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems in Iran's Natanz uranium enrichment facility by exploiting four zero-day vulnerabilities in Windows and Siemens Step7 software to manipulate programmable logic controllers, causing physical damage to approximately 1,000 centrifuges while concealing alterations through rootkit techniques.[44] Attributed to a joint U.S.-Israeli operation, it spread primarily via USB drives and network shares, infecting over 200,000 computers globally but activating payloads only on specific air-gapped targets, demonstrating worms' potential for precision cyber-physical disruption over indiscriminate damage.[44] Follow-up variants like Duqu, identified in September 2011, extended Stuxnet's modular architecture for espionage, stealing certificates and data from industrial targets in Europe and Iran using similar kernel exploits to maintain persistence.[45] Flame, uncovered in May 2012, introduced advanced modularity with over 20MB of code, including Bluetooth propagation and screenshot capture, primarily affecting systems in the Middle East for intelligence gathering, with capabilities to self-destruct or mimic legitimate updates.[45] Shamoon, deployed in August 2012 against Saudi Aramco, functioned as a destructive wiper worm, overwriting master boot records and data on 35,000 workstations via shared networks, rendering 75% of the company's systems inoperable and highlighting worms' role in asymmetric industrial sabotage.[45] In the late 2010s, worms integrated with ransomware for rapid propagation, as seen in WannaCry's May 2017 outbreak, which leveraged the EternalBlue exploit in unpatched Windows SMBv1 to self-replicate across 150 countries, encrypting data on over 200,000 systems and demanding Bitcoin ransoms totaling around $140,000 before a kill switch halted spread.[46] NotPetya, launched in June 2017, masqueraded as ransomware but primarily wiped data through EternalBlue and credential dumping for lateral movement, disrupting Ukrainian infrastructure and global firms like Maersk, with estimated damages exceeding $10 billion due to its aggressive network traversal mimicking worm autonomy.[47] The 2020s saw worms targeting software supply chains, exemplified by the Shai-Hulud worm detected in September 2025, which self-replicated across npm repositories by hijacking developer accounts, injecting malicious YAML files into GitHub workflows to exfiltrate secrets and propagate via automated commits, compromising hundreds of packages in a novel ecosystem-specific attack vector.[48] Emerging concepts like AI worms, which hypothetically leverage machine learning for adaptive evasion and propagation without traditional exploits, reflect ongoing evolution toward intelligent, less detectable variants, though real-world instances remain limited to proof-of-concepts as of 2025.[49] Overall, contemporary worms have trended from broad internet-scale outbreaks to targeted, state-linked or profit-driven operations exploiting zero-days and unpatched legacy systems, with reduced emphasis on pure mass replication due to enhanced endpoint detection.[50]Technical Mechanisms

Self-Replication and Autonomy

A computer worm's self-replication begins with the execution of its core code on an infected host, which triggers routines to generate identical copies of the worm's binary or script payload. These copies are created by leveraging system calls for file duplication or memory allocation, ensuring the replica includes all necessary components for independent operation, such as propagation logic and evasion techniques.[51] [11] Upon successful transfer to a new host via network protocols like TCP or UDP, the replica exploits the target's environment to self-install, often by writing to temporary directories or modifying startup processes, thereby initiating its own replication cycle without external dependencies.[52] [53] Autonomy in worms manifests as their capacity to operate as self-contained programs that make propagation decisions algorithmically, independent of user intervention or attachment to legitimate files. This contrasts with viruses, which require human-executed hosts to activate; worms instead exploit inherent network connectivity and vulnerabilities autonomously, using embedded scanning algorithms to identify targets and execute transfers.[23] [54] For instance, the worm's code may incorporate random number generators for IP address selection or predefined hit-lists for efficiency, allowing it to persist and replicate across diverse systems without manual propagation.[55] [56] Such independence enables exponential spread, as each instance acts as both victim and vector, amplifying infection rates through recursive execution.[57]Propagation and Exploitation Methods

Computer worms propagate primarily through autonomous scanning of network address spaces to identify and infect vulnerable hosts, exploiting software flaws to deliver payloads without user intervention.[58] Common scanning strategies include random scanning, where target IP addresses are selected uniformly at random from the available space, leading to exponential growth in infections until vulnerable hosts are depleted; hit-list scanning, utilizing a pre-compiled directory of targets for rapid initial spread; and permutation scanning, which systematically traverses the address space in a pseudo-random order to avoid redundancy.[58][53] Exploitation typically involves remote code execution vulnerabilities, such as buffer overflows, where malformed input overflows allocated memory to overwrite execution control structures and inject malicious code.[59] For instance, the Code Red worm, released on July 15, 2001, exploited a buffer overflow in Microsoft IIS index server by sending a long string of repeated 'N' characters to trigger the vulnerability, enabling shellcode execution for self-replication.[59] Similarly, the Morris worm of November 2, 1988, targeted Unix systems via buffer overflows in the fingerd daemon, a debug mode in sendmail, and weak authentication in rsh/rexec services assuming trusted host relationships.[60] These techniques allow worms to gain sufficient privileges to copy themselves, often masking propagation through methods like "hook-and-haul" to obscure entry points.[60] Beyond pure network scanning, worms employ hybrid vectors including dictionary attacks on weakly protected network shares, as seen in Conficker (first detected November 2008), which brute-forced SMB shares alongside exploiting the MS08-067 RPC vulnerability; removable media autorun exploits for local network hopping; and social vectors like email attachments or peer-to-peer file sharing that trigger upon execution.[61][62] Propagation efficiency depends on factors like scan rate limits to evade detection, topological awareness from infected hosts' routing tables, and fallback to multiple exploits for resilience against patches.[63] Such methods enable worms to achieve infection rates of millions of hosts rapidly, as with Conficker infecting up to 15 million systems by early 2009.[61]Payload Execution and Effects

Once a computer worm successfully propagates to a target system—typically via exploitation of software vulnerabilities such as buffer overflows or weak authentication—the payload executes autonomously, often as an integrated module within the worm's codebase or as a separately downloaded component triggered post-infection. This execution leverages the gained privileges, such as system-level access obtained through the initial exploit, to perform actions beyond mere replication; for instance, shellcode injected during propagation may decode and run the main payload, which then modifies system files, registries, or processes without requiring further user interaction.[64][61] Payload effects range from resource denial to data manipulation and remote control establishment, calibrated by the worm's design objectives, which may prioritize disruption, espionage, or sabotage. Resource exhaustion occurs when payloads spawn excessive processes or network traffic, as exemplified by the Morris worm on November 2, 1988, which, due to a replication bug, infected approximately 6,000 Unix systems (about 10% of the internet at the time), forking processes that consumed up to 99% of CPU cycles and rendered machines unresponsive for days.[65] In contrast, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) payloads coordinate infected hosts into botnets for targeted flooding; the Blaster worm (discovered August 11, 2003) exploited Windows DCOM RPC vulnerabilities to infect over 500,000 systems, executing a payload that queued UDP SYN packets at 50 per second to windowsupdate.com starting August 16, 2003, while displaying an anti-Microsoft message on infected screens.[66][67] Backdoor and persistence mechanisms enable ongoing control, often by disabling defenses and phoning home to command-and-control (C2) servers; Conficker (first detected November 21, 2008) infected millions of Windows machines via MS08-067 exploits, executing a payload that disabled Windows Update, Windows Defender, and antivirus services, then used domain generation algorithms to fetch additional malware for botnet operations like spam or further attacks.[7][61] Data theft or alteration payloads exfiltrate sensitive information or corrupt files, though some worms like Code Red (July 13, 2001) focused on symbolic disruption by temporarily defacing IIS web servers with "Hacked By Chinese!" messages before restoring content after roughly 10 hours and attempting DDoS on whitehouse.gov.[68][69] Advanced payloads achieve physical impacts through targeted manipulations; Stuxnet (discovered June 2010) exploited multiple zero-days in Windows and Siemens PLC firmware to infiltrate Iran's Natanz uranium enrichment facility, where its payload subtly altered centrifuge speeds—accelerating to 1,410 Hz then decelerating to 2 Hz or halting—causing over 1,000 IR-1 centrifuges to fail prematurely between late 2009 and early 2010, while falsifying sensor data to evade detection via rootkit techniques.[70] Such effects underscore payloads' potential for cascading failures, where initial code execution amplifies into systemic overload or targeted destruction, often evading immediate notice through stealth features like anti-forensic measures.[71]Impacts and Consequences

Direct Harms and Empirical Damages

Computer worms inflict direct harms primarily through resource exhaustion, unauthorized data access, encryption or deletion of files, and disruption of critical systems, leading to measurable operational downtime and recovery costs. These effects stem from the worm's self-replication, which consumes bandwidth and processing power, often causing denial-of-service conditions without requiring user interaction. Empirical data from notable incidents quantify these damages in billions of dollars globally, encompassing cleanup expenses, lost productivity, and hardware strain.[72] The Code Red worm, propagating in July 2001, exemplifies rapid direct impact by exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft IIS servers, infecting over 250,000 systems within nine hours and generating defacement payloads alongside massive traffic floods. This resulted in widespread server crashes and network overloads, with economic losses exceeding $2.4 billion, including $1.1 billion in remediation and $1.5 billion in productivity halts across affected enterprises.[72][73] The SQL Slammer worm in January 2003 further demonstrated bandwidth saturation harms, spreading to hundreds of thousands of Microsoft SQL Server instances in under 10 minutes via UDP packets, triggering outages at banks, airlines, and ISPs without a destructive payload beyond the propagation itself; damages totaled over $750 million in direct cleanup and downtime costs.[74] More recent worms combining propagation with payloads have amplified data-centric harms. Conficker, emerging in November 2008, infected approximately 11 million Windows machines by exploiting unpatched RPC flaws and weak passwords, enabling backdoor access that facilitated further malware deployment and system instability; potential direct losses reached $9.1 billion, including specific incidents like a UK local authority's £1.4 million recovery expenditure.[75][76] NotPetya, deploying in June 2017 via worm-like EternalBlue exploits initially targeting Ukrainian systems but spreading globally, encrypted master boot records and files, rendering machines inoperable and causing over $10 billion in verified damages to firms like Merck ($1.7 billion in lost inventory and production) through irrecoverable data loss and operational halts.[77][78] Similarly, WannaCry's May 2017 outbreak encrypted data on over 200,000 systems in 150 countries, directly crippling healthcare providers like the UK's NHS—where 19,000 appointments were canceled—and incurring global remediation and downtime costs estimated at $4 billion.[79][80] These cases highlight causal links between worm autonomy and harms: self-replication overwhelms infrastructure, while payloads enforce data unavailability, with costs empirically tied to infection scale and sector vulnerability rather than indirect factors. Early worms like Morris in 1988 caused less quantified financial damage—around $100 million in cleanup for 6,000 infected machines—primarily via resource denial without encryption, underscoring evolution toward more destructive mechanisms.[81] Recovery universally demands manual intervention, patching, and sometimes full system wipes, amplifying direct empirical burdens on unpatched environments.[82]Broader Systemic and Geopolitical Effects

The deployment of sophisticated computer worms by state actors has reshaped geopolitical rivalries, enabling covert sabotage of adversaries' capabilities without traditional military engagement. Stuxnet, first identified in June 2010 and attributed to a collaborative effort by U.S. and Israeli intelligence agencies, infiltrated Iran's Natanz nuclear facility, causing approximately 1,000 uranium enrichment centrifuges to fail through manipulated programmable logic controllers, thereby delaying Tehran's nuclear program by up to two years. This operation, which exploited four zero-day vulnerabilities in Windows and Siemens software, marked a precedent for cyber weapons achieving physical destruction, but its escape into the wild infected non-target systems globally, heightening tensions over attribution and retaliation norms in cyberspace.[83][84] Subsequent worms have amplified hybrid warfare strategies, blending cyber disruption with conventional conflicts. In June 2017, NotPetya—believed to originate from Russia's Sandworm group amid the Ukraine crisis—initially masqueraded as ransomware but propagated via Ukrainian tax software updates, exploiting the EternalBlue vulnerability to encrypt data worldwide. The attack paralyzed Ukraine's power grid, airports, and banks while inflicting collateral damages exceeding $10 billion across global firms like Maersk and Merck, disrupting international shipping and pharmaceutical production for weeks. Such spillover effects strained diplomatic relations, with the U.S. and EU imposing sanctions on implicated Russian entities, underscoring worms' role in proxy escalations that challenge sovereignty and economic interdependence.[85][86] WannaCry, unleashed in May 2017 and linked to North Korea's Lazarus Group, leveraged the same EternalBlue exploit to encrypt files on over 200,000 systems across 150 countries, demanding Bitcoin ransoms that yielded minimal returns but exposed regime funding motives. It halted operations at Britain's National Health Service—cancelling 19,000 appointments and costing £92 million—and FedEx, while prompting a White House attribution to Pyongyang that intensified U.S. sanctions and cyber diplomacy efforts. These incidents collectively eroded trust in shared digital ecosystems, fueling debates on offensive cyber restraint, as evidenced by stalled UN Group of Governmental Experts talks on applying international law to state-sponsored intrusions.[47][87][88] On a systemic level, worms exploit interconnected infrastructures to trigger cascading failures, amplifying localized exploits into economy-wide shocks that reveal inherent fragilities in unpatched, legacy-dependent networks. NotPetya and WannaCry, by leveraging NSA-derived tools leaked via Shadow Brokers in 2016, demonstrated how proliferation of nation-state exploits undermines global stability, with aggregate losses from such events estimated in tens of billions and prompting regulatory mandates like the EU's NIS Directive updates. These outbreaks have spurred systemic responses, including heightened private-sector investments—reaching $150 billion globally in 2023—and national strategies emphasizing supply-chain security, as worms' autonomy bypasses perimeter defenses to propagate via routine updates and protocols. Persistent threats like Conficker, infecting up to 15 million machines since 2008, further illustrate long-tail risks to botnet recruitment for DDoS or espionage, eroding resilience in financial and utility sectors without direct geopolitical intent.[89][90][52]Countermeasures and Mitigation

Detection and Analysis Techniques

Detection of computer worms relies on a combination of signature-based, anomaly-based, and behavioral methods tailored to their self-propagating nature. Signature-based detection scans network traffic, system logs, or files for predefined patterns associated with known worms, such as specific byte sequences in payloads or propagation code.[91] This approach achieves low false-positive rates but requires prior knowledge of the worm and struggles against variants that mutate signatures.[92] Anomaly-based intrusion detection systems identify deviations from baseline network or host behavior, such as sudden spikes in outbound scanning traffic indicative of worm propagation.[92] Behavioral techniques focus on the inherent propagation patterns of worms, distinguishing them from benign traffic. Behavioral footprinting profiles a worm's infection sessions—sequences of scan, exploit, and replication actions—by extracting features like timing intervals, packet structures, and response dependencies from captured traffic traces.[93] This method has been evaluated on real worms including Code Red and variants, enabling detection without relying on content signatures.[94] Systems like vEye apply sequence alignment algorithms to match observed infection patterns against worm behavioral templates, capturing self-propagation even in obfuscated samples.[95] Endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools monitor for abnormal host activities, such as rapid file creation or unauthorized network connections, which signal autonomous replication.[13] Machine learning enhances detection by modeling worm scanning behaviors; for instance, ensemble classifiers combine features from network packets to identify self-propagating scans with high accuracy in simulated environments.[96] The SWORD detector targets core worm traits like target generation and exploitation attempts, using sequential hypothesis testing to confirm propagation without evasion by polymorphism.[97] Analysis of captured worm samples involves static and dynamic reverse engineering to dissect replication mechanisms and payloads. Static analysis examines binaries without execution, parsing headers, strings, and API calls to reveal propagation logic, such as vulnerability exploits or network protocols used.[98] Tools like disassemblers convert machine code to assembly for identifying self-replication routines, as applied to worms like Stuxnet, which required x86 expertise to uncover zero-day exploits.[99] Dynamic analysis executes samples in isolated sandboxes to observe runtime behavior, including propagation attempts and payload activation, while logging system calls and network interactions.[100] Forensic techniques trace worm artifacts, such as modified registry entries or droppers, to reconstruct infection chains and assess damage potential.[101] These methods, often combined, enable attribution and signature generation for broader defenses, though evasion via packing or anti-analysis code necessitates iterative refinement.[102]Preventive Measures and Best Practices

Applying security patches promptly addresses known vulnerabilities exploited by worms, such as the buffer overflow in the SMB protocol targeted by the 2008 Conficker worm, which affected millions of Windows systems before patches were widely deployed.[12][103] Antivirus and anti-malware software with real-time scanning and automatic updates detect self-replicating code and quarantine infections before propagation, as recommended for desktop and server environments.[2][12] Firewalls, both host-based and network-level, block unauthorized inbound connections and filter traffic on vulnerable ports, mitigating worms that scan for open services like those used by the 1988 Morris worm.[104][105]- Software updates and patch management: Automate updates for operating systems, applications, and firmware to close exploits; for instance, unpatched systems remain primary vectors for worms years after vulnerability disclosure.[103][12]

- Endpoint protection platforms: Deploy tools with behavioral analysis to identify anomalous replication patterns beyond signature-based detection.[12]

- Network segmentation: Isolate critical systems using VLANs or micro-segmentation to limit lateral movement, containing outbreaks like those observed in enterprise networks.[106]

- Email and web filtering: Scan attachments and links for malicious payloads, blocking domains known for worm distribution; disable AutoRun features to prevent execution from removable media.[107]

- Access controls: Enforce least privilege principles, strong authentication including multi-factor where feasible, and monitor for privilege escalation attempts.[108][105]

- User training: Educate on recognizing phishing vectors, avoiding unverified downloads, and reporting anomalies, as human error facilitates initial infections in over 90% of malware incidents per industry analyses.[106]

- Regular backups and testing: Maintain offline backups of critical data, tested for restorability, to enable recovery without paying ransoms or yielding to destructive payloads.[107][106]