Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

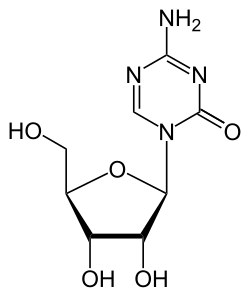

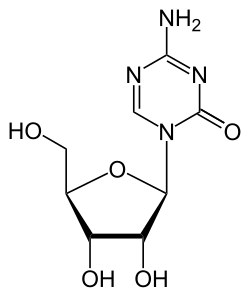

Azacitidine

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Vidaza, Azadine, Onureg |

| Other names | 5-Azacytidine, Azacytidine, Ladakamycin, 4-Amino-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-s-triazin-2(1H)-one, U-18496, CC-486 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607068 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous, intravenous, by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 4 hr.[8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.711 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H12N4O5 |

| Molar mass | 244.207 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Azacitidine, sold under the brand name Vidaza among others, is a medication used for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome, myeloid leukemia,[5][6] and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.[4][9] It is a chemical analog of cytidine, a nucleoside in DNA and RNA.[medical citation needed] Azacitidine and its deoxy derivative, decitabine (also known as 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine) were first synthesized in Czechoslovakia as potential chemotherapeutic agents for cancer.[10]

The most common adverse reactions in children with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia include pyrexia, rash, upper respiratory tract infection, and anemia.[9]

Medical uses

[edit]Azacitidine is indicated for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome,[4] for which it received approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 19 May 2004.[11][4][12] In two randomized controlled trials comparing azacitidine to supportive treatment, 16% of subjects with myelodysplastic syndrome who were randomized to receive azacitidine had a complete or partial normalization of blood cell counts and bone marrow morphology, compared to none who received supportive care, and about two-thirds of patients who required blood transfusions no longer needed them after receiving azacitidine.[13]

Azacitidine is also indicated for the treatment of myeloid leukemia[5][6][14] and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.[4][9] The combination of azacitidine and venetoclax is also approved for AML.[15]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Azacitidine is a chemical analogue of the nucleoside cytidine, which is present in DNA and RNA. It is thought to have antineoplastic activity via two mechanisms – at low doses, by inhibiting of DNA methyltransferase, causing hypomethylation of DNA,[16] and at high doses, by its direct cytotoxicity to abnormal hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow through its incorporation into DNA and RNA, resulting in cell death. Azacitidine is a ribonucleoside, so it is incorporated into RNA to a larger extent than into DNA. In contrast, decitabine (5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine) is a deoxyribonucleoside, so it can only incorporate into DNA. Azacitidine's incorporation into RNA leads to the disassembly of polyribosomes, defective methylation and acceptor function of transfer RNA, and inhibition of the production of proteins. Its incorporation into DNA leads to covalent binding with DNA methyltransferases, which prevents DNA synthesis and subsequently leads to cytotoxicity. It has been shown effective against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro[17] and human T-lymphotropic virus.[18]

Inhibition of methylation

[edit]After azanucleosides such as azacitidine have been metabolized to 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine-triphosphate (aka, decitabine-triphosphate), they can be incorporated into DNA and azacytosine can be substituted for cytosine. Azacytosine-guanine dinucleotides are recognized as substrate by the DNA methyltransferases, which catalyze the methylation reaction by a nucleophilic attack. This results in a covalent bond between the carbon-6 atom of the cytosine ring and the enzyme. The bond is normally resolved by beta-elimination through the carbon-5 atom, but this latter reaction does not occur with azacytosine because its carbon-5 is substituted by nitrogen, leaving the enzyme covalently bound to DNA and blocking its DNA methyltransferase function. In addition, the covalent protein adduction also compromises the functionality of DNA and triggers DNA damage signaling, resulting in the degradation of trapped DNA methyltransferases. As a consequence, methylation marks become lost during DNA replication.[19][20]

Toxicity

[edit]Azacitidine causes anemia (low red blood cell counts), neutropenia (low white blood cell counts), and thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts), and patients should have frequent monitoring of their complete blood counts, at least prior to each dosing cycle. The dose may have to be adjusted based on nadir counts and hematologic response.[4]

It can also be hepatotoxic in patients with severe liver impairment, and patients with extensive liver tumors due to metastatic disease have developed progressive hepatic coma and death during azacitidine treatment, especially when their albumin levels are less than 30 g/L. It is contraindicated in patients with advanced malignant hepatic tumors.[4]

Kidney toxicity, ranging from elevated serum creatinine to kidney failure and death, have been reported in patients treated with intravenous azacitidine in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents for conditions other than myelodysplastic syndrome. Renal tubular acidosis developed in five patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (an unapproved use) treated with azacitidine and etoposide, and patients with renal impairment may be at increased risk for renal toxicity. Azacitidine and its metabolites are primarily excreted by the kidneys, so patients with chronic kidney disease should be closely monitored for other side effects, since their levels of azacitidine may progressively increase.[4]

Based on animal studies and its mechanism of action, azacitidine can cause severe fetal damage. Sexually active women of reproductive potential should use contraception while receiving azacitidine and for one week after the last dose, and sexually active men with female partners of reproductive potential should use contraception during treatment and for three months following the last dose.[4]

A study undertaken to evaluate the immediate and long-term effects of a single-day exposure to Azacytidine (5-AzaC) on neurobehavioral abnormalities in mice found, that the inhibition of DNA methylation by 5-AzaC treatment causes neurodegeneration and impairs extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) activation and the activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated (Arc) protein expression in neonatal mice and induces behavioral abnormalities in adult mice, as DNA methylation-mediated mechanisms appear to be necessary for the proper maturation of synaptic circuits during development, and disruption of this process by 5-AzaC could lead to abnormal cognitive function.[21]

Azacitidine can also cause nausea, vomiting, fevers, diarrhea, redness at its injection sites, constipation, bruising, petechiae, rigors, weakness, abnormally low potassium levels in the bloodstream, and many other side effects, some of which can be severe or even fatal.[4]

History

[edit]The efficacy of azacitidine to treat juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia was evaluated in AZA-JMML-001 (NCT02447666), an international, multicenter, open-label study to evaluate the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and activity of azacitidine prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in 18 pediatric patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.[9]

Research

[edit]Azacitidine can be used in vitro to remove methyl groups from DNA. This may weaken the effects of gene silencing mechanisms that occur prior to methylation. Certain methylations are believed to secure DNA in a silenced state, and therefore demethylation may reduce the stability of silencing signals and confer relative gene activation.[22]

Azacitidine induces tumor regression on isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 mutant glioma xenografts in mice.[23]

In research, 5-azacitidine is commonly used for promoting cardiomyocyte differentiation of adult stem cells. However, it has been suggested that this drug has a compromised efficacy as a cardiac differentiation factor because it promotes the transdifferentiation of cardiac cells to skeletal myocytes.[24]

Azacitidine also has antiviral effects in animal studies as well as its anti-cancer actions, but has not been tested for clinical use.[25][26]

References

[edit]- ^ "Azacitidine (Vidaza) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 5 May 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Vidaza- azacitidine injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution". DailyMed. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "Onureg- azacitidine tablet, film coated". DailyMed. 20 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "Onureg EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 20 April 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ "Onureg Product information". Union Register of medicinal products. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- ^ Vallerand AH, Deglin JH (2009). Davis's drug guide for nurses. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. pp. 204–206. ISBN 978-0-8036-1912-8.

- ^ a b c d "FDA approves azacitidine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 20 May 2022. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Cihák A (1974). "Biological effects of 5-azacytidine in eukaryotes". Oncology. 30 (5): 405–22. doi:10.1159/000224981. PMID 4142650.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Vidaza (Azacitidine) NDA #050794". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 14 July 2004. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations". fda.gov. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 23 May 2006. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ Kaminskas E, Farrell AT, Wang YC, Sridhara R, Pazdur R (March 2005). "FDA drug approval summary: azacitidine (5-azacytidine, Vidaza) for injectable suspension". The Oncologist. 10 (3): 176–82. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.10-3-176. PMID 15793220. S2CID 11375964.

- ^ Molica M, Mazzone C, Niscola P, Carmosino I, Di Veroli A, De Gregoris C, et al. (October 2022). "Identification of Predictive Factors for Overall Survival and Response during Hypomethylating Treatment in Very Elderly (≥75 Years) Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients: A Multicenter Real-Life Experience". Cancers. 14 (19): 4897. doi:10.3390/cancers14194897. PMC 9564161. PMID 36230820.

- ^ DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, et al. (August 2020). "Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (7): 617–629. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2012971. hdl:2078.1/241045. PMID 32786187. S2CID 221121486.

- ^ Martens UM, ed. (2010). "11 5-Azacytidine/Azacitidine". Small molecules in oncology. Recent Results in Cancer Research. Vol. 184. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 159–170. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01222-8. ISBN 978-3-642-01222-8.

- ^ Dapp MJ, Clouser CL, Patterson S, Mansky LM (November 2009). "5-Azacytidine can induce lethal mutagenesis in human immunodeficiency virus type 1". Journal of Virology. 83 (22): 11950–8. doi:10.1128/JVI.01406-09. PMC 2772699. PMID 19726509.

- ^ Diamantopoulos PT, Michael M, Benopoulou O, Bazanis E, Tzeletas G, Meletis J, Vayopoulos G, Viniou NA (January 2012). "Antiretroviral activity of 5-azacytidine during treatment of a HTLV-1 positive myelodysplastic syndrome with autoimmune manifestations". Virology Journal. 9: 1. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-9-1. PMC 3305386. PMID 22214262.

- ^ Stresemann C, Lyko F (July 2008). "Modes of action of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitors azacytidine and decitabine". International Journal of Cancer. 123 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1002/ijc.23607. PMID 18425818. S2CID 14125490.

- ^ Navada SC, Steinmann J, Lübbert M, Silverman LR (January 2014). "Clinical development of demethylating agents in hematology". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 124 (1): 40–6. doi:10.1172/JCI69739. PMC 3871232. PMID 24382388.

- ^ Subbanna S, Nagre NN, Shivakumar M, Basavarajappa BS (December 2016). "A single day of 5-azacytidine exposure during development induces neurodegeneration in neonatal mice and neurobehavioral deficits in adult mice". Physiology & Behavior. 167: 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.08.036. PMC 5159185. PMID 27594097.

- ^ Whitelaw E, Garrick D (2005). "Chapter 7: The Epigenome". In Ruvinsky A, Marshall Graves JA (eds.). Mammalian Genomics. Wallingford, U.K.: CABI Publishing. ISBN 0-85199-910-7.

- ^ Borodovsky A, Salmasi V, Turcan S, Fabius AW, Baia GS, Eberhart CG, et al. (October 2013). "5-azacytidine reduces methylation, promotes differentiation and induces tumor regression in a patient-derived IDH1 mutant glioma xenograft". Oncotarget. 4 (10): 1737–47. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1408. PMC 3858560. PMID 24077805.

- ^ Kaur K, Yang J, Eisenberg CA, Eisenberg LM (October 2014). "5-azacytidine promotes the transdifferentiation of cardiac cells to skeletal myocytes". Cellular Reprogramming. 16 (5): 324–30. doi:10.1089/cell.2014.0021. PMID 25090621.

- ^ Wang X, Zou P, Wu F, Lu L, Jiang S (December 2017). "Development of small-molecule viral inhibitors targeting various stages of the life cycle of emerging and re-emerging viruses". Frontiers of Medicine. 11 (4): 449–461. doi:10.1007/s11684-017-0589-5. PMC 7089273. PMID 29170916.

- ^ Ianevski A, Zusinaite E, Kuivanen S, Strand M, Lysvand H, Teppor M, et al. (June 2018). "Novel activities of safe-in-human broad-spectrum antiviral agents". Antiviral Research. 154: 174–182. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.04.016. hdl:10138/301108. PMC 7113852. PMID 29698664.

External links

[edit]- Clinical trial number NCT02447666 for "Study With Azacitidine in Pediatric Subjects With Newly Diagnosed Advanced Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) and Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML)" at ClinicalTrials.gov