Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

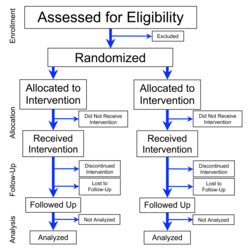

Randomized controlled trial

View on Wikipedia

A randomized controlled trial (abbreviated RCT) is a type of scientific experiment designed to evaluate the efficacy or safety of an intervention by minimizing bias through the random allocation of participants to one or more comparison groups.[2]

In this design, at least one group receives the intervention under study (such as a drug, surgical procedure, medical device, diet, or diagnostic test), while another group receives an alternative treatment, a placebo, or standard care.[3][4]

RCTs are a fundamental methodology in modern clinical trials and are considered one of the highest-quality sources of evidence in evidence-based medicine, due to their ability to reduce selection bias and the influence of confounding factors.

Participants who enroll in RCTs differ from one another in known and unknown ways that can influence study outcomes, and yet cannot be directly controlled. By randomly allocating participants among compared treatments, an RCT enables statistical control over these influences. Provided it is designed well, conducted properly, and enrolls enough participants, an RCT may achieve sufficient control over these confounding factors to deliver a useful comparison of the treatments studied.

Definition and examples

[edit]An RCT in clinical research typically compares a proposed new treatment against an existing standard of care; these are then termed the 'experimental' and 'control' treatments, respectively. When no such generally accepted treatment is available, a placebo may be used in the control group so that participants are blinded, or not given information, about their treatment allocations. This blinding principle is ideally also extended as much as possible to other parties including researchers, technicians, data analysts, and evaluators. Effective blinding experimentally isolates the physiological effects of treatments from various psychological sources of bias.[citation needed]

The randomness in the assignment of participants to treatments reduces selection bias and allocation bias, balancing both known and unknown prognostic factors, in the assignment of treatments.[5] Blinding reduces other forms of experimenter and subject biases.[citation needed]

A well-blinded RCT is considered the gold standard for clinical trials. Blinded RCTs are commonly used to test the efficacy of medical interventions and may additionally provide information about adverse effects, such as drug reactions. A randomized controlled trial can provide compelling evidence that the study treatment causes an effect on human health.[6]

The terms "RCT" and "randomized trial" are sometimes used synonymously, but the latter term omits mention of controls and can therefore describe studies that compare multiple treatment groups with each other in the absence of a control group.[7] Similarly, the initialism is sometimes expanded as "randomized clinical trial" or "randomized comparative trial", leading to ambiguity in the scientific literature.[8][9] Not all RCTs are randomized controlled trials (and some of them could never be, as in cases where controls would be impractical or unethical to use). The term randomized controlled clinical trial is an alternative term used in clinical research;[10] however, RCTs are also employed in other research areas, including many of the social sciences.

History

[edit]In the posthumously published Ortus Medicinae (1648), Jan Baptist van Helmont made the first proposal of a RCT, to test two treatment regimes of fever. One treatment would be conducted by practitioners of Galenic medicine involving bloodletting and purging, and the other would be conducted by van Helmont. It is likely that he never conducted the trial, and merely proposed it as an experiment that could be conducted.[11]

The first reported clinical trial was conducted by James Lind in 1747 to identify a treatment for scurvy.[12] The first blind experiment was conducted by the French Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism in 1784 to investigate the claims of mesmerism. An early essay advocating the blinding of researchers came from Claude Bernard in the latter half of the 19th century.[vague] Bernard recommended that the observer of an experiment should not have knowledge of the hypothesis being tested. This suggestion contrasted starkly with the prevalent Enlightenment-era attitude that scientific observation can only be objectively valid when undertaken by a well-educated, informed scientist.[13] The first study recorded to have a blinded researcher was published in 1907 by W. H. R. Rivers and H. N. Webber to investigate the effects of caffeine.[14]

Randomized experiments first appeared in psychology, where they were introduced by Charles Sanders Peirce and Joseph Jastrow in the 1880s,[15] and in education.[16][17][18] The earliest experiments comparing treatment and control groups were published by Robert Woodworth and Edward Thorndike in 1901,[19] and by John E. Coover and Frank Angell in 1907.[20][21]

In the early 20th century, randomized experiments appeared in agriculture, due to Jerzy Neyman[22] and Ronald A. Fisher. Fisher's experimental research and his writings popularized randomized experiments.[23]

The first published Randomized Controlled Trial in medicine appeared in the 1948 paper entitled "Streptomycin treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis", which described a Medical Research Council investigation.[24][25][26] One of the authors of that paper was Austin Bradford Hill, who is credited as having conceived the modern RCT.[27]

Trial design was further influenced by the large-scale ISIS trials on heart attack treatments that were conducted in the 1980s.[28]

By the late 20th century, RCTs were recognized as the standard method for "rational therapeutics" in medicine.[29] As of 2004, more than 150,000 RCTs were in the Cochrane Library.[27] To improve the reporting of RCTs in the medical literature, an international group of scientists and editors published Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statements in 1996, 2001 and 2010, and these have become widely accepted.[1][5]

Ethics

[edit]Although the principle of clinical equipoise ("genuine uncertainty within the expert medical community... about the preferred treatment") common to clinical trials[30] has been applied to RCTs, the ethics of RCTs have special considerations. For one, it has been argued that equipoise itself is insufficient to justify RCTs.[31] For another, "collective equipoise" can conflict with a lack of personal equipoise (e.g., a personal belief that an intervention is effective).[32] Finally, Zelen's design, which has been used for some RCTs, randomizes subjects before they provide informed consent, which may be ethical for RCTs of screening and selected therapies, but is likely unethical "for most therapeutic trials."[33][34]

Although subjects almost always provide informed consent for their participation in an RCT, studies since 1982 have documented that RCT subjects may believe that they are certain to receive treatment that is best for them personally; that is, they do not understand the difference between research and treatment.[35][36] Further research is necessary to determine the prevalence of and ways to address this "therapeutic misconception".[36]

The RCT method variations may also create cultural effects that have not been well understood.[37] For example, patients with terminal illness may join trials in the hope of being cured, even when treatments are unlikely to be successful.[citation needed]

Trial registration

[edit]In 2004, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) announced that all trials starting enrolment after July 1, 2005, must be registered prior to consideration for publication in one of the 12 member journals of the committee.[38] However, trial registration may still occur late or not at all.[39][40] Medical journals have been slow in adapting policies requiring mandatory clinical trial registration as a prerequisite for publication.[41]

Classifications

[edit]By study design

[edit]One way to classify RCTs is by study design. From most to least common in the healthcare literature, the major categories of RCT study designs are:[42]

- Parallel-group – each participant is randomly assigned to a group, and all the participants in the group receive (or do not receive) an intervention.[43][44]

- Crossover – over time, each participant receives (or does not receive) an intervention in a random sequence.[45][46]

- Stepped-wedge trial - " involves random and sequential crossover of clusters (of subjects) from control to intervention until all clusters are exposed."[47] In the past, this design has been called a "waiting list designs" or "phased implementations."[47]

- Cluster – pre-existing groups of participants (e.g., villages, schools) are randomly selected to receive (or not receive) an intervention.[48][49]

- Factorial – each participant is randomly assigned to a group that receives a particular combination of interventions or non-interventions (e.g., group 1 receives vitamin X and vitamin Y, group 2 receives vitamin X and placebo Y, group 3 receives placebo X and vitamin Y, and group 4 receives placebo X and placebo Y).

An analysis of the 616 RCTs indexed in PubMed during December 2006 found that 78% were parallel-group trials, 16% were crossover, 2% were split-body, 2% were cluster, and 2% were factorial.[42]

By outcome of interest (efficacy vs. effectiveness)

[edit]RCTs can be classified as "explanatory" or "pragmatic."[50] Explanatory RCTs test efficacy in a research setting with highly selected participants and under highly controlled conditions.[50] In contrast, pragmatic RCTs (pRCTs) test effectiveness in everyday practice with relatively unselected participants and under flexible conditions; in this way, pragmatic RCTs can "inform decisions about practice."[50]

By hypothesis (superiority vs. noninferiority vs. equivalence)

[edit]Another classification of RCTs categorizes them as "superiority trials", "noninferiority trials", and "equivalence trials", which differ in methodology and reporting.[51] Most RCTs are superiority trials, in which one intervention is hypothesized to be superior to another in a statistically significant way.[51] Some RCTs are noninferiority trials "to determine whether a new treatment is no worse than a reference treatment."[51] Other RCTs are equivalence trials in which the hypothesis is that two interventions are indistinguishable from each other.[51]

Randomization

[edit]The advantages of proper randomization in RCTs include:[52]

- "It eliminates bias in treatment assignment," specifically selection bias and confounding.

- "It facilitates blinding (masking) of the identity of treatments from investigators, participants, and assessors."

- "It permits the use of probability theory to express the likelihood that any difference in outcome between treatment groups merely indicates chance."

There are two processes involved in randomizing patients to different interventions. First is choosing a randomization procedure to generate an unpredictable sequence of allocations; this may be a simple random assignment of patients to any of the groups at equal probabilities, may be "restricted", or may be "adaptive." A second and more practical issue is allocation concealment, which refers to the stringent precautions taken to ensure that the group assignment of patients are not revealed prior to definitively allocating them to their respective groups. Non-random "systematic" methods of group assignment, such as alternating subjects between one group and the other, can cause "limitless contamination possibilities" and can cause a breach of allocation concealment.[53]

However empirical evidence that adequate randomization changes outcomes relative to inadequate randomization has been difficult to detect.[54]

Procedures

[edit]The treatment allocation is the desired proportion of patients in each treatment arm.

An ideal randomization procedure would achieve the following goals:[55]

- Maximize statistical power, especially in subgroup analyses. Generally, equal group sizes maximize statistical power, however, unequal groups sizes may be more powerful for some analyses (e.g., multiple comparisons of placebo versus several doses using Dunnett's procedure[56] ), and are sometimes desired for non-analytic reasons (e.g., patients may be more motivated to enroll if there is a higher chance of getting the test treatment, or regulatory agencies may require a minimum number of patients exposed to treatment).[57]

- Minimize selection bias. This may occur if investigators can consciously or unconsciously preferentially enroll patients between treatment arms. A good randomization procedure will be unpredictable so that investigators cannot guess the next subject's group assignment based on prior treatment assignments. The risk of selection bias is highest when previous treatment assignments are known (as in unblinded studies) or can be guessed (perhaps if a drug has distinctive side effects).

- Minimize allocation bias (or confounding). This may occur when covariates that affect the outcome are not equally distributed between treatment groups, and the treatment effect is confounded with the effect of the covariates (i.e., an "accidental bias"[52][58]). If the randomization procedure causes an imbalance in covariates related to the outcome across groups, estimates of effect may be biased if not adjusted for the covariates (which may be unmeasured and therefore impossible to adjust for).

However, no single randomization procedure meets those goals in every circumstance, so researchers must select a procedure for a given study based on its advantages and disadvantages.[citation needed]

Simple

[edit]This is a commonly used and intuitive procedure, similar to "repeated fair coin-tossing."[52] Also known as "complete" or "unrestricted" randomization, it is robust against both selection and accidental biases. However, its main drawback is the possibility of imbalanced group sizes in small RCTs. It is therefore recommended only for RCTs with over 200 subjects.[59]

Restricted

[edit]To balance group sizes in smaller RCTs, some form of "restricted" randomization is recommended.[59] The major types of restricted randomization used in RCTs are:

- Permuted-block randomization or blocked randomization: a "block size" and "allocation ratio" (number of subjects in one group versus the other group) are specified, and subjects are allocated randomly within each block.[53] For example, a block size of 6 and an allocation ratio of 2:1 would lead to random assignment of 4 subjects to one group and 2 to the other. This type of randomization can be combined with "stratified randomization", for example by center in a multicenter trial, to "ensure good balance of participant characteristics in each group."[5] A special case of permuted-block randomization is random allocation, in which the entire sample is treated as one block.[53] The major disadvantage of permuted-block randomization is that even if the block sizes are large and randomly varied, the procedure can lead to selection bias.[55] Another disadvantage is that "proper" analysis of data from permuted-block-randomized RCTs requires stratification by blocks.[59]

- Adaptive biased-coin randomization methods (of which urn randomization is the most widely known type): In these relatively uncommon methods, the probability of being assigned to a group decreases if the group is overrepresented and increases if the group is underrepresented.[53] The methods are thought to be less affected by selection bias than permuted-block randomization.[59]

Adaptive

[edit]At least two types of "adaptive" randomization procedures have been used in RCTs, but much less frequently than simple or restricted randomization:

- Covariate-adaptive randomization, of which one type is minimization: The probability of being assigned to a group varies in order to minimize "covariate imbalance."[59] Minimization is reported to have "supporters and detractors"[53] because only the first subject's group assignment is truly chosen at random, the method does not necessarily eliminate bias on unknown factors.[5]

- Response-adaptive randomization, also known as outcome-adaptive randomization: The probability of being assigned to a group increases if the responses of the prior patients in the group were favorable.[59] Although arguments have been made that this approach is more ethical than other types of randomization when the probability that a treatment is effective or ineffective increases during the course of an RCT, ethicists have not yet studied the approach in detail.[60]

Allocation concealment

[edit]"Allocation concealment" (defined as "the procedure for protecting the randomization process so that the treatment to be allocated is not known before the patient is entered into the study") is important in RCTs.[61] In practice, clinical investigators in RCTs often find it difficult to maintain impartiality. Stories abound of investigators holding up sealed envelopes to lights or ransacking offices to determine group assignments in order to dictate the assignment of their next patient.[53] Such practices introduce selection bias and confounders (both of which should be minimized by randomization), possibly distorting the results of the study.[53] Adequate allocation concealment should defeat patients and investigators from discovering treatment allocation once a study is underway and after the study has concluded. Treatment related side-effects or adverse events may be specific enough to reveal allocation to investigators or patients thereby introducing bias or influencing any subjective parameters collected by investigators or requested from subjects.[citation needed]

Some standard methods of ensuring allocation concealment include sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE); sequentially numbered containers; pharmacy controlled randomization; and central randomization.[53] It is recommended that allocation concealment methods be included in an RCT's protocol, and that the allocation concealment methods should be reported in detail in a publication of an RCT's results; however, a 2005 study determined that most RCTs have unclear allocation concealment in their protocols, in their publications, or both.[62] On the other hand, a 2008 study of 146 meta-analyses concluded that the results of RCTs with inadequate or unclear allocation concealment tended to be biased toward beneficial effects only if the RCTs' outcomes were subjective as opposed to objective.[63]

Sample size

[edit]The number of treatment units (subjects or groups of subjects) assigned to control and treatment groups, affects an RCT's reliability. If the effect of the treatment is small, the number of treatment units in either group may be insufficient for rejecting the null hypothesis in the respective statistical test. The failure to reject the null hypothesis would imply that the treatment shows no statistically significant effect on the treated in a given test. But as the sample size increases, the same RCT may be able to demonstrate a significant effect of the treatment, even if this effect is small.[64]

Blinding

[edit]An RCT may be blinded, (also called "masked") by "procedures that prevent study participants, caregivers, or outcome assessors from knowing which intervention was received."[63] Unlike allocation concealment, blinding is sometimes inappropriate or impossible to perform in an RCT; for example, if an RCT involves a treatment in which active participation of the patient is necessary (e.g., physical therapy), participants cannot be blinded to the intervention.[citation needed]

Traditionally, blinded RCTs have been classified as "single-blind", "double-blind", or "triple-blind"; however, in 2001 and 2006 two studies showed that these terms have different meanings for different people.[65][66] The 2010 CONSORT Statement specifies that authors and editors should not use the terms "single-blind", "double-blind", and "triple-blind"; instead, reports of blinded RCT should discuss "If done, who was blinded after assignment to interventions (for example, participants, care providers, those assessing outcomes) and how."[5]

RCTs without blinding are referred to as "unblinded",[67] "open",[68] or (if the intervention is a medication) "open-label".[69] In 2008 a study concluded that the results of unblinded RCTs tended to be biased toward beneficial effects only if the RCTs' outcomes were subjective as opposed to objective;[63] for example, in an RCT of treatments for multiple sclerosis, unblinded neurologists (but not the blinded neurologists) felt that the treatments were beneficial.[70] In pragmatic RCTs, although the participants and providers are often unblinded, it is "still desirable and often possible to blind the assessor or obtain an objective source of data for evaluation of outcomes."[50]

Analysis of data

[edit]The types of statistical methods used in RCTs depend on the characteristics of the data and include:

- For dichotomous (binary) outcome data, logistic regression (e.g., to predict sustained virological response after receipt of peginterferon alfa-2a for hepatitis C[71]) and other methods can be used.

- For continuous outcome data, analysis of covariance (e.g., for changes in blood lipid levels after receipt of atorvastatin after acute coronary syndrome[72]) tests the effects of predictor variables.

- For time-to-event outcome data that may be censored, survival analysis (e.g., Kaplan–Meier estimators and Cox proportional hazards models for time to coronary heart disease after receipt of hormone replacement therapy in menopause[73]) is appropriate.

Regardless of the statistical methods used, important considerations in the analysis of RCT data include:

- Whether an RCT should be stopped early due to interim results. For example, RCTs may be stopped early if an intervention produces "larger than expected benefit or harm", or if "investigators find evidence of no important difference between experimental and control interventions."[5]

- The extent to which the groups can be analyzed exactly as they existed upon randomization (i.e., whether a so-called "intention-to-treat analysis" is used). A "pure" intention-to-treat analysis is "possible only when complete outcome data are available" for all randomized subjects;[74] when some outcome data are missing, options include analyzing only cases with known outcomes and using imputed data.[5] Nevertheless, the more that analyses can include all participants in the groups to which they were randomized, the less bias that an RCT will be subject to.[5]

- Whether subgroup analysis should be performed. These are "often discouraged" because multiple comparisons may produce false positive findings that cannot be confirmed by other studies.[5]

Reporting of results

[edit]The CONSORT 2010 Statement is "an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting RCTs."[75] The CONSORT 2010 checklist contains 25 items (many with sub-items) focusing on "individually randomised, two group, parallel trials" which are the most common type of RCT.[1]

For other RCT study designs, "CONSORT extensions" have been published, some examples are:

- Consort 2010 Statement: Extension to Cluster Randomised Trials[76]

- Consort 2010 Statement: Non-Pharmacologic Treatment Interventions[77][78]

- "Reporting of surrogate endpoints in randomised controlled trial reports (CONSORT-Surrogate): extension checklist with explanation and elaboration"[79]

Relative importance and observational studies

[edit]Two studies published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2000 found that observational studies and RCTs overall produced similar results.[80][81] The authors of the 2000 findings questioned the belief that "observational studies should not be used for defining evidence-based medical care" and that RCTs' results are "evidence of the highest grade."[80][81] However, a 2001 study published in Journal of the American Medical Association concluded that "discrepancies beyond chance do occur and differences in estimated magnitude of treatment effect are very common" between observational studies and RCTs.[82] According to a 2014 (updated in 2024) Cochrane review, there is little evidence for significant effect differences between observational studies and randomized controlled trials.[83] To evaluate differences it is necessary to consider things other than design, such as heterogeneity, population, intervention or comparator.[83]

Two other lines of reasoning question RCTs' contribution to scientific knowledge beyond other types of studies:

- If study designs are ranked by their potential for new discoveries, then anecdotal evidence[broken anchor] would be at the top of the list, followed by observational studies, followed by RCTs.[84]

- RCTs may be unnecessary for treatments that have dramatic and rapid effects relative to the expected stable or progressively worse natural course of the condition treated.[85][86] One example is combination chemotherapy including cisplatin for metastatic testicular cancer, which increased the cure rate from 5% to 60% in a 1977 non-randomized study.[86][87]

Interpretation of statistical results

[edit]Like all statistical methods, RCTs are subject to both type I ("false positive") and type II ("false negative") statistical errors. Regarding Type I errors, a typical RCT will use 0.05 (i.e., 1 in 20) as the probability that the RCT will falsely find two equally effective treatments significantly different.[88] Regarding Type II errors, despite the publication of a 1978 paper noting that the sample sizes of many "negative" RCTs were too small to make definitive conclusions about the negative results,[89] by 2005-2006 a sizeable proportion of RCTs still had inaccurate or incompletely reported sample size calculations.[90]

Peer review

[edit]Peer review of results is an important part of the scientific method. Reviewers examine the study results for potential problems with design that could lead to unreliable results (for example by creating a systematic bias), evaluate the study in the context of related studies and other evidence, and evaluate whether the study can be reasonably considered to have proven its conclusions. To underscore the need for peer review and the danger of overgeneralizing conclusions, two Boston-area medical researchers performed a randomized controlled trial in which they randomly assigned either a parachute or an empty backpack to 23 volunteers who jumped from either a biplane or a helicopter. The study was able to accurately report that parachutes fail to reduce injury compared to empty backpacks. The key context that limited the general applicability of this conclusion was that the aircraft were parked on the ground, and participants had only jumped about two feet.[91]

Advantages

[edit]RCTs are considered to be the most reliable form of scientific evidence in the hierarchy of evidence that influences healthcare policy and practice because RCTs reduce spurious causality and bias. Results of RCTs may be combined in systematic reviews which are increasingly being used in the conduct of evidence-based practice. Some examples of scientific organizations' considering RCTs or systematic reviews of RCTs to be the highest-quality evidence available are:

- As of 1998, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia designated "Level I" evidence as that "obtained from a systematic review of all relevant randomised controlled trials" and "Level II" evidence as that "obtained from at least one properly designed randomised controlled trial."[92]

- Since at least 2001, in making clinical practice guideline recommendations the United States Preventive Services Task Force has considered both a study's design and its internal validity as indicators of its quality.[93] It has recognized "evidence obtained from at least one properly randomized controlled trial" with good internal validity (i.e., a rating of "I-good") as the highest quality evidence available to it.[93]

- The GRADE Working Group concluded in 2008 that "randomised trials without important limitations constitute high quality evidence."[94]

- For issues involving "Therapy/Prevention, Aetiology/Harm", the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine as of 2011 defined "Level 1a" evidence as a systematic review of RCTs that are consistent with each other, and "Level 1b" evidence as an "individual RCT (with narrow Confidence Interval)."[95]

Notable RCTs with unexpected results that contributed to changes in clinical practice include:

- After Food and Drug Administration approval, the antiarrhythmic agents flecainide and encainide came to market in 1986 and 1987 respectively.[96] The non-randomized studies concerning the drugs were characterized as "glowing",[97] and their sales increased to a combined total of approximately 165,000 prescriptions per month in early 1989.[96] In that year, however, a preliminary report of an RCT concluded that the two drugs increased mortality.[98] Sales of the drugs then decreased.[96]

- Prior to 2002, based on observational studies, it was routine for physicians to prescribe hormone replacement therapy for post-menopausal women to prevent myocardial infarction.[97] In 2002 and 2004, however, published RCTs from the Women's Health Initiative claimed that women taking hormone replacement therapy with estrogen plus progestin had a higher rate of myocardial infarctions than women on a placebo, and that estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy caused no reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease.[73][99] Possible explanations for the discrepancy between the observational studies and the RCTs involved differences in methodology, in the hormone regimens used, and in the populations studied.[100][101] The use of hormone replacement therapy decreased after publication of the RCTs.[102]

Disadvantages

[edit]Many papers discuss the disadvantages of RCTs.[85][103][104] Among the most frequently cited drawbacks are:

Time and costs

[edit]RCTs can be expensive;[104] one study found 28 Phase III RCTs funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke prior to 2000 with a total cost of US$335 million,[105] for a mean cost of US$12 million per RCT. Nevertheless, the return on investment of RCTs may be high, in that the same study projected that the 28 RCTs produced a "net benefit to society at 10-years" of 46 times the cost of the trials program, based on evaluating a quality-adjusted life year as equal to the prevailing mean per capita gross domestic product.[105]

The conduct of an RCT takes several years until being published; thus, data is restricted from the medical community for long years and may be of less relevance at time of publication.[106]

It is costly to maintain RCTs for the years or decades that would be ideal for evaluating some interventions.[85][104]

Interventions to prevent events that occur only infrequently (e.g., sudden infant death syndrome) and uncommon adverse outcomes (e.g., a rare side effect of a drug) would require RCTs with extremely large sample sizes and may, therefore, best be assessed by observational studies.[85]

Due to the costs of running RCTs, these usually only inspect one variable or very few variables, rarely reflecting the full picture of a complicated medical situation; whereas the case report, for example, can detail many aspects of the patient's medical situation (e.g. patient history, physical examination, diagnosis, psychosocial aspects, follow up).[106]

Conflict of interest dangers

[edit]A 2011 study done to disclose possible conflicts of interests in underlying research studies used for medical meta-analyses reviewed 29 meta-analyses and found that conflicts of interests in the studies underlying the meta-analyses were rarely disclosed. The 29 meta-analyses included 11 from general medicine journals; 15 from specialty medicine journals, and 3 from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The 29 meta-analyses reviewed an aggregate of 509 randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Of these, 318 RCTs reported funding sources with 219 (69%) industry funded. 132 of the 509 RCTs reported author conflict of interest disclosures, with 91 studies (69%) disclosing industry financial ties with one or more authors. The information was, however, seldom reflected in the meta-analyses. Only two (7%) reported RCT funding sources and none reported RCT author-industry ties. The authors concluded "without acknowledgment of COI due to industry funding or author industry financial ties from RCTs included in meta-analyses, readers' understanding and appraisal of the evidence from the meta-analysis may be compromised."[107]

Some RCTs are fully or partly funded by the health care industry (e.g., the pharmaceutical industry) as opposed to government, nonprofit, or other sources. A systematic review published in 2003 found four 1986–2002 articles comparing industry-sponsored and nonindustry-sponsored RCTs, and in all the articles there was a correlation of industry sponsorship and positive study outcome.[108] A 2004 study of 1999–2001 RCTs published in leading medical and surgical journals determined that industry-funded RCTs "are more likely to be associated with statistically significant pro-industry findings."[109] These results have been mirrored in trials in surgery, where although industry funding did not affect the rate of trial discontinuation it was however associated with a lower odds of publication for completed trials.[110] One possible reason for the pro-industry results in industry-funded published RCTs is publication bias.[109] Other authors have cited the differing goals of academic and industry sponsored research as contributing to the difference. Commercial sponsors may be more focused on performing trials of drugs that have already shown promise in early stage trials, and on replicating previous positive results to fulfill regulatory requirements for drug approval.[111]

Ethics

[edit]If a disruptive innovation in medical technology is developed, it may be difficult to test this ethically in an RCT if it becomes "obvious" that the control subjects have poorer outcomes—either due to other foregoing testing, or within the initial phase of the RCT itself. Ethically it may be necessary to abort the RCT prematurely, and getting ethics approval (and patient agreement) to withhold the innovation from the control group in future RCTs may not be feasible.[citation needed]

Historical control trials (HCT) exploit the data of previous RCTs to reduce the sample size; however, these approaches are controversial in the scientific community and must be handled with care.[112]

In social science

[edit]Due to the recent emergence of RCTs in social science, the use of RCTs in social sciences is a contested issue. Some writers from a medical or health background have argued that existing research in a range of social science disciplines lacks rigour, and should be improved by greater use of randomized control trials.[113]

Transport science

[edit]Researchers in transport science argue that public spending on programmes such as school travel plans could not be justified unless their efficacy is demonstrated by randomized controlled trials.[114] Graham-Rowe and colleagues[115] reviewed 77 evaluations of transport interventions found in the literature, categorising them into 5 "quality levels". They concluded that most of the studies were of low quality and advocated the use of randomized controlled trials wherever possible in future transport research.

Dr. Steve Melia[116] took issue with these conclusions, arguing that claims about the advantages of RCTs, in establishing causality and avoiding bias, have been exaggerated. He proposed the following eight criteria for the use of RCTs in contexts where interventions must change human behaviour to be effective:

The intervention:

- Has not been applied to all members of a unique group of people (e.g. the population of a whole country, all employees of a unique organisation etc.)

- Is applied in a context or setting similar to that which applies to the control group

- Can be isolated from other activities—and the purpose of the study is to assess this isolated effect

- Has a short timescale between its implementation and maturity of its effects

And the causal mechanisms:

- Are either known to the researchers, or else all possible alternatives can be tested

- Do not involve significant feedback mechanisms between the intervention group and external environments

- Have a stable and predictable relationship to exogenous factors

- Would act in the same way if the control group and intervention group were reversed

Criminology

[edit]A 2005 review found 83 randomized experiments in criminology published in 1982–2004, compared with only 35 published in 1957–1981.[117] The authors classified the studies they found into five categories: "policing", "prevention", "corrections", "court", and "community".[117] Focusing only on offending behavior programs, Hollin (2008) argued that RCTs may be difficult to implement (e.g., if an RCT required "passing sentences that would randomly assign offenders to programmes") and therefore that experiments with quasi-experimental design are still necessary.[118]

Education

[edit]RCTs have been used in evaluating a number of educational interventions. Between 1980 and 2016, over 1,000 reports of RCTs have been published.[119] For example, a 2009 study randomized 260 elementary school teachers' classrooms to receive or not receive a program of behavioral screening, classroom intervention, and parent training, and then measured the behavioral and academic performance of their students.[120] Another 2009 study randomized classrooms for 678 first-grade children to receive a classroom-centered intervention, a parent-centered intervention, or no intervention, and then followed their academic outcomes through age 19.[121]

Criticism

[edit]A 2018 review of the 10 most cited randomised controlled trials noted poor distribution of background traits, difficulties with blinding, and discussed other assumptions and biases inherent in randomised controlled trials. These include the "unique time period assessment bias", the "background traits remain constant assumption", the "average treatment effects limitation", the "simple treatment at the individual level limitation", the "all preconditions are fully met assumption", the "quantitative variable limitation" and the "placebo only or conventional treatment only limitation".[122]

See also

[edit]- Drug development

- Hypothesis testing

- Impact evaluation

- Jadad scale

- Pipeline planning

- Patient and public involvement

- Observational study

- Blinded experiment

- Statistical inference

- Royal Commission on Animal Magnetism – 1784 French scientific bodies' investigations involving systematic controlled trials

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. (CONSORT Group) (March 2010). "CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials". BMJ. 340: c332. doi:10.1136/bmj.c332. PMC 2844940. PMID 20332509.

- ^ Chalmers TC, Smith H, Blackburn B, et al. (May 1981). "A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial". Controlled Clinical Trials. 2 (1): 31–49. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8. PMID 7261638.

- ^ "What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?". National Institute on Aging, US National Institutes of Health. 22 March 2023. Archived from the original on November 14, 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "What Are the Different Types of Clinical Research?". US Food and Drug Administration. 4 January 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. (March 2010). "CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials". BMJ. 340: c869. doi:10.1136/bmj.c869. PMC 2844943. PMID 20332511.

- ^ Hannan EL (June 2008). "Randomized clinical trials and observational studies: guidelines for assessing respective strengths and limitations". JACC. Cardiovascular Interventions. 1 (3): 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2008.01.008. PMID 19463302.

- ^ Ranjith G (2005). "Interferon-alpha-induced depression: when a randomized trial is not a randomized controlled trial". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 74 (6): 387, author reply 387-387, author reply 388. doi:10.1159/000087787. PMID 16244516. S2CID 143644933.

- ^ Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. (December 1976). "Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design". British Journal of Cancer. 34 (6): 585–612. doi:10.1038/bjc.1976.220. PMC 2025229. PMID 795448.

- ^ Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. (January 1977). "Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. II. analysis and examples". British Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1038/bjc.1977.1. PMC 2025310. PMID 831755.

- ^ Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, et al. (2004). "Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial". Lancet. 364 (9429): 141–148. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16626-9. PMID 15246726. S2CID 24361586.

- ^ Donaldson I (September 2016). "Van Helmont's Proposal for a Randomised Comparison of Treating Fevers with or without Bloodletting and Purging". Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 46 (3): 206–213. doi:10.4997/jrcpe.2016.313. ISSN 1478-2715.

- ^ Dunn PM (January 1997). "James Lind (1716-94) of Edinburgh and the treatment of scurvy". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 76 (1): F64 – F65. doi:10.1136/fn.76.1.f64. PMC 1720613. PMID 9059193.

- ^ Daston L (2005). "Scientific Error and the Ethos of Belief". Social Research. 72 (1): 18. doi:10.1353/sor.2005.0016. S2CID 141036212.

- ^ Rivers WH, Webber HN (August 1907). "The action of caffeine on the capacity for muscular work". The Journal of Physiology. 36 (1): 33–47. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1907.sp001215. PMC 1533733. PMID 16992882.

- ^ Peirce CS, Jastrow J (1885). "On Small Differences in Sensation". Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences. 3: 73–83. http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Peirce/small-diffs.htm

- ^ Hacking I (September 1988). "Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design". Isis. A Special Issue on Artifact and Experiment. 79 (3): 427–451. doi:10.1086/354775. JSTOR 234674. MR 1013489. S2CID 52201011.

- ^ Stigler SM (November 1992). "A Historical View of Statistical Concepts in Psychology and Educational Research". American Journal of Education. 101 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1086/444032. S2CID 143685203.

- ^ Dehue T (December 1997). "Deception, efficiency, and random groups. Psychology and the gradual origination of the random group design" (PDF). Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 88 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1086/383850. PMID 9519574. S2CID 23526321.

- ^ Woodworth RS, ThorndikeEL (1901). "The influence of improvement in one mental function upon the efficiency of other functions (I)" (PDF). Psychological Review. 8 (3): 247. doi:10.1037/h0074898.

- ^ Coover JE, Angell F (1907). "General Practice Effect of Special Exercise". The American Journal of Psychology. 18 (3): 328–340. doi:10.2307/1412596. ISSN 0002-9556. JSTOR 1412596.

- ^ Dehue T (2000). "From deception trials to control reagents: The introduction of the control group about a century ago" (PDF). American Psychologist. 55 (2): 264–268. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.2.264. ISSN 1935-990X. Archived from the original on 12 Jul 2024.

- ^ Neyman, Jerzy. 1923 [1990]. "On the Application of Probability Theory to AgriculturalExperiments. Essay on Principles. Section 9." Statistical Science 5 (4): 465–472. Trans. Dorota M. Dabrowska and Terence P. Speed.

- ^

According to Denis Conniffe:

Ronald A. Fisher was "interested in application and in the popularization of statistical methods and his early book Statistical Methods for Research Workers, published in 1925, went through many editions and motivated and influenced the practical use of statistics in many fields of study. His Design of Experiments (1935) [promoted] statistical technique and application. In that book he emphasized examples and how to design experiments systematically from a statistical point of view. The mathematical justification of the methods described was not stressed and, indeed, proofs were often barely sketched or omitted altogether ..., a fact which led H. B. Mann to fill the gaps with a rigorous mathematical treatment in his well known treatise, Mann (1949)."

Conniffe D (1990–1991). "R. A. Fisher and the development of statistics—a view in his centenary year". Journal of the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland. Vol. XXVI, no. 3. Dublin: Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland. p. 87. hdl:2262/2764. ISSN 0081-4776.

Mann HB (1949). Analysis and design of experiments: Analysis of variance and analysis of variance designs. New York: Dover Publications. MR 0032177. - ^ Streptomycin in Tuberculosis Trials Committee (October 1948). "STREPTOMYCIN treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis". British Medical Journal. 2 (4582): 769–782. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4582.769. PMC 2091872. PMID 18890300.

- ^ Brown D (1998-11-02). "Landmark study made research resistant to bias". Washington Post.

- ^ Shikata S, Nakayama T, Noguchi Y, et al. (November 2006). "Comparison of effects in randomized controlled trials with observational studies in digestive surgery". Annals of Surgery. 244 (5): 668–676. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000225356.04304.bc. PMC 1856609. PMID 17060757.

- ^ a b Stolberg HO, Norman G, Trop I (December 2004). "Randomized controlled trials". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 183 (6): 1539–1544. doi:10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831539. PMID 15547188. S2CID 5376391.

- ^ Ferry G (2 November 2020). "Peter Sleight Obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ Meldrum ML (August 2000). "A brief history of the randomized controlled trial. From oranges and lemons to the gold standard". Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 14 (4): 745–60, vii. doi:10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70309-9. PMID 10949771.

- ^ Freedman B (July 1987). "Equipoise and the ethics of clinical research". The New England Journal of Medicine. 317 (3): 141–145. doi:10.1056/NEJM198707163170304. PMID 3600702.

- ^ Gifford F (April 1995). "Community-equipoise and the ethics of randomized clinical trials". Bioethics. 9 (2): 127–148. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.1995.tb00306.x. PMID 11653056.

- ^ Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ, Hewison J (October 1998). "The ethics of randomised controlled trials from the perspectives of patients, the public, and healthcare professionals". BMJ. 317 (7167): 1209–1212. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7167.1209. PMC 1114158. PMID 9794861.

- ^ Zelen M (May 1979). "A new design for randomized clinical trials". The New England Journal of Medicine. 300 (22): 1242–1245. doi:10.1056/NEJM197905313002203. PMID 431682.

- ^ Torgerson DJ, Roland M (February 1998). "What is Zelen's design?". BMJ. 316 (7131): 606. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7131.606. PMC 1112637. PMID 9518917.

- ^ Appelbaum PS, Roth LH, Lidz C (1982). "The therapeutic misconception: informed consent in psychiatric research". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 5 (3–4): 319–329. doi:10.1016/0160-2527(82)90026-7. PMID 6135666.

- ^ a b Henderson GE, Churchill LR, Davis AM, et al. (November 2007). "Clinical trials and medical care: defining the therapeutic misconception". PLOS Medicine. 4 (11) e324. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324. PMC 2082641. PMID 18044980.

- ^ Jain SL (2010). "The mortality effect: counting the dead in the cancer trial" (PDF). Public Culture. 21 (1): 89–117. doi:10.1215/08992363-2009-017. S2CID 143641293. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-20.

- ^ De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. (September 2004). "Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors". The New England Journal of Medicine. 351 (12): 1250–1251. doi:10.1056/NEJMe048225. PMID 15356289.

- ^ Law MR, Kawasumi Y, Morgan SG (December 2011). "Despite law, fewer than one in eight completed studies of drugs and biologics are reported on time on ClinicalTrials.gov". Health Affairs. 30 (12): 2338–2345. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0172. PMID 22147862.

- ^ Mathieu S, Boutron I, Moher D, et al. (September 2009). "Comparison of registered and published primary outcomes in randomized controlled trials". JAMA. 302 (9): 977–984. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1242. PMID 19724045.

- ^ Bhaumik S, Biswas T (March 2013). "Editorial policies of MEDLINE indexed Indian journals on clinical trial registration". Indian Pediatrics. 50 (3): 339–340. doi:10.1007/s13312-013-0092-2. PMID 23680610. S2CID 40317464.

- ^ a b Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, et al. (March 2010). "The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed". BMJ. 340: c723. doi:10.1136/bmj.c723. PMC 2844941. PMID 20332510.

- ^ Kaiser J, Niesen W, Probst P, et al. (June 2019). "Abdominal drainage versus no drainage after distal pancreatectomy: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial". Trials. 20 (1): 332. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3442-0. PMC 6555976. PMID 31174583.

- ^ Farag SM, Mohammed MO, El-Sobky TA, et al. (March 2020). "Botulinum Toxin A Injection in Treatment of Upper Limb Spasticity in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". JBJS Reviews. 8 (3) e0119. doi:10.2106/JBJS.RVW.19.00119. PMC 7161716. PMID 32224633.

- ^ Jones B, Kenward MG (2003). Design and Analysis of Cross-Over Trials (Second ed.). London: Chapman and Hall.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Vonesh EF, Chinchilli VG (1997). "Crossover Experiments". Linear and Nonlinear Models for the Analysis of Repeated Measurements. London: Chapman and Hall. pp. 111–202.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ a b Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. (February 2015). "The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting". BMJ. 350: h391. doi:10.1136/bmj.h391. PMID 25662947.

- ^ Gall S, Adams L, Joubert N, et al. (8 November 2018). "Effect of a 20-week physical activity intervention on selective attention and academic performance in children living in disadvantaged neighborhoods: A cluster randomized control trial". PLOS ONE. 13 (11) e0206908. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1306908G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206908. PMC 6224098. PMID 30408073.

- ^ Gladstone MJ, Chandna J, Kandawasvika G, et al. (March 2019). "Independent and combined effects of improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) and improved complementary feeding on early neurodevelopment among children born to HIV-negative mothers in rural Zimbabwe: Substudy of a cluster-randomized trial". PLOS Medicine. 16 (3) e1002766. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002766. PMC 6428259. PMID 30897095.

- ^ a b c d Zwarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, et al. (November 2008). "Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement". BMJ. 337 a2390. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2390. PMC 3266844. PMID 19001484.

- ^ a b c d Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, et al. (March 2006). "Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement" (PDF). JAMA. 295 (10): 1152–1160. doi:10.1001/jama.295.10.1152. PMID 16522836.

- ^ a b c Schulz KF, Grimes DA (February 2002). "Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice". Lancet. 359 (9305): 515–519. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3. PMID 11853818. S2CID 291300.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schulz KF, Grimes DA (February 2002). "Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering" (PDF). Lancet. 359 (9306): 614–618. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4. PMID 11867132. S2CID 12902486. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2012.

- ^ Howick J, Mebius A (December 2014). "In search of justification for the unpredictability paradox". Trials. 15: 480. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-15-480. PMC 4295227. PMID 25490908.

- ^ a b Lachin JM (December 1988). "Statistical properties of randomization in clinical trials". Controlled Clinical Trials. 9 (4): 289–311. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(88)90045-1. PMID 3060315.

- ^ Rosenberger J. "STAT 503 - Design of Experiments". Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Avins AL (December 1998). "Can unequal be more fair? Ethics, subject allocation, and randomised clinical trials". Journal of Medical Ethics. 24 (6): 401–408. doi:10.1136/jme.24.6.401. PMC 479141. PMID 9873981.

- ^ Buyse ME (December 1989). "Analysis of clinical trial outcomes: some comments on subgroup analyses". Controlled Clinical Trials. 10 (4 Suppl): 187S – 194S. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(89)90057-3. PMID 2605967.

- ^ a b c d e f Lachin JM, Matts JP, Wei LJ (December 1988). "Randomization in clinical trials: conclusions and recommendations". Controlled Clinical Trials. 9 (4): 365–374. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(88)90049-9. hdl:2027.42/27041. PMID 3203526.

- ^ Rosenberger WF, Lachin JM (December 1993). "The use of response-adaptive designs in clinical trials". Controlled Clinical Trials. 14 (6): 471–484. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(93)90028-C. PMID 8119063.

- ^ Forder PM, Gebski VJ, Keech AC (January 2005). "Allocation concealment and blinding: when ignorance is bliss". The Medical Journal of Australia. 182 (2): 87–89. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06584.x. PMID 15651970. S2CID 202149.

- ^ Pildal J, Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, et al. (May 2005). "Comparison of descriptions of allocation concealment in trial protocols and the published reports: cohort study". BMJ. 330 (7499): 1049. doi:10.1136/bmj.38414.422650.8F. PMC 557221. PMID 15817527.

- ^ a b c Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, et al. (March 2008). "Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: meta-epidemiological study". BMJ. 336 (7644): 601–605. doi:10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD. PMC 2267990. PMID 18316340.

- ^ Glennerster R, Kudzai T (2013). ""Chapter 6"". Running randomized evaluations: a practical guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgd52. ISBN 978-0-691-15924-9. JSTOR j.ctt4cgd52.

- ^ Devereaux PJ, Manns BJ, Ghali WA, et al. (April 2001). "Physician interpretations and textbook definitions of blinding terminology in randomized controlled trials". JAMA. 285 (15): 2000–2003. doi:10.1001/jama.285.15.2000. PMID 11308438.

- ^ Haahr MT, Hróbjartsson A (2006). "Who is blinded in randomized clinical trials? A study of 200 trials and a survey of authors". Clinical Trials. 3 (4): 360–365. doi:10.1177/1740774506069153. PMID 17060210. S2CID 23818514.

- ^ Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M, et al. (March 2007). "The SANAD study of effectiveness of valproate, lamotrigine, or topiramate for generalised and unclassifiable epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 369 (9566): 1016–1026. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60461-9. PMC 2039891. PMID 17382828.

- ^ Chan R, Hemeryck L, O'Regan M, et al. (May 1995). "Oral versus intravenous antibiotics for community acquired lower respiratory tract infection in a general hospital: open, randomised controlled trial". BMJ. 310 (6991): 1360–1362. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6991.1360. PMC 2549744. PMID 7787537.

- ^ Fukase K, Kato M, Kikuchi S, et al. (August 2008). "Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 372 (9636): 392–397. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61159-9. hdl:2115/34681. PMID 18675689. S2CID 13741892.

- ^ Noseworthy JH, Ebers GC, Vandervoort MK, et al. (January 1994). "The impact of blinding on the results of a randomized, placebo-controlled multiple sclerosis clinical trial". Neurology. 44 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1212/wnl.44.1.16. PMID 8290055. S2CID 2663997. Archived from the original on 2005-05-10. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ^ Manns MP, McHutchison JG, Gordon SC, et al. (September 2001). "Peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin compared with interferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin for initial treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a randomised trial". Lancet. 358 (9286): 958–965. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06102-5. PMID 11583749. S2CID 14583372.

- ^ Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, et al. (April 2001). "Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: the MIRACL study: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 285 (13): 1711–1718. doi:10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. PMID 11277825.

- ^ a b Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. (July 2002). "Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 288 (3): 321–333. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321. PMID 12117397. S2CID 20149703.

- ^ Hollis S, Campbell F (September 1999). "What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 319 (7211): 670–674. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. PMC 28218. PMID 10480822.

- ^ CONSORT Group. "Welcome to the CONSORT statement Website". Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2010-03-29.

- ^ Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. (September 2012). "Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials". BMJ. 345 e5661. doi:10.1136/bmj.e5661. hdl:2164/2742. PMC 381234. PMID 22951546.

- ^ Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, et al. (February 2008). "Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration". Annals of Internal Medicine. 148 (4): 295–309. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. PMID 18283207.

- ^ Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, et al. (February 2008). "Methods and processes of the CONSORT Group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments". Annals of Internal Medicine. 148 (4): W60 – W66. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008-w1. PMID 18283201.

- ^ Manyara AM, Davies P, Stewart D, et al. (July 2024). "Reporting of surrogate endpoints in randomised controlled trial reports (CONSORT-Surrogate): extension checklist with explanation and elaboration". BMJ. 386 e078524. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-078524. PMC 11231881. PMID 38981645.

- ^ a b Benson K, Hartz AJ (June 2000). "A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (25): 1878–1886. doi:10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. PMID 10861324.

- ^ a b Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RI (June 2000). "Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs". The New England Journal of Medicine. 342 (25): 1887–1892. doi:10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. PMC 1557642. PMID 10861325.

- ^ Ioannidis JP, Haidich AB, Pappa M, et al. (August 2001). "Comparison of evidence of treatment effects in randomized and nonrandomized studies". JAMA. 286 (7): 821–830. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.590.2854. doi:10.1001/jama.286.7.821. PMID 11497536.

- ^ a b Toews I, Anglemyer A, Nyirenda JL, et al. (2024-01-04). "Healthcare outcomes assessed with observational study designs compared with those assessed in randomized trials: a meta-epidemiological study". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): MR000034. doi:10.1002/14651858.MR000034.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 10765475. PMID 38174786.

- ^ Vandenbroucke JP (March 2008). "Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science". PLOS Medicine. 5 (3) e67. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050067. PMC 2265762. PMID 18336067.

- ^ a b c d Black N (May 1996). "Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care". BMJ. 312 (7040): 1215–1218. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. PMC 2350940. PMID 8634569.

- ^ a b Glasziou P, Chalmers I, Rawlins M, et al. (February 2007). "When are randomised trials unnecessary? Picking signal from noise". BMJ. 334 (7589): 349–351. doi:10.1136/bmj.39070.527986.68. PMC 1800999. PMID 17303884.

- ^ Einhorn LH (April 2002). "Curing metastatic testicular cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (7): 4592–4595. doi:10.1073/pnas.072067999. PMC 123692. PMID 11904381.

- ^ Wittes J (2002). "Sample size calculations for randomized controlled trials". Epidemiologic Reviews. 24 (1): 39–53. doi:10.1093/epirev/24.1.39. PMID 12119854.

- ^ Freiman JA, Chalmers TC, Smith H, et al. (September 1978). "The importance of beta, the type II error and sample size in the design and interpretation of the randomized control trial. Survey of 71 "negative" trials". The New England Journal of Medicine. 299 (13): 690–694. doi:10.1056/NEJM197809282991304. PMID 355881.

- ^ Charles P, Giraudeau B, Dechartres A, et al. (May 2009). "Reporting of sample size calculation in randomised controlled trials: review". BMJ. 338 b1732. doi:10.1136/bmj.b1732. PMC 2680945. PMID 19435763.

- ^ Harris R (22 Dec 2018). "Researchers Show Parachutes Don't Work, But There's A Catch". NPR. Archived from the original on Jan 17, 2024.

- ^ National Health and Medical Research Council (1998-11-16). A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines (PDF). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-86496-048-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-14. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ a b Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. (Methods Work Group; Third US Preventive Services Task Force) (April 2001). "Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 20 (3 Suppl): 21–35. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6. PMID 11306229.

- ^ Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. (GRADE Working Group) (May 2008). "What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians?". BMJ. 336 (7651): 995–998. doi:10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. PMC 2364804. PMID 18456631.

- ^ Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine (2011-09-16). "Levels of evidence". Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ a b c Anderson JL, Pratt CM, Waldo AL, et al. (January 1997). "Impact of the Food and Drug Administration approval of flecainide and encainide on coronary artery disease mortality: putting "Deadly Medicine" to the test". The American Journal of Cardiology. 79 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(96)00673-X. PMID 9024734.

- ^ a b Rubin R (2006-10-16). "In medicine, evidence can be confusing - deluged with studies, doctors try to sort out what works, what doesn't". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

- ^ Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators (August 1989). "Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (6): 406–412. doi:10.1056/NEJM198908103210629. PMID 2473403.

- ^ Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. (April 2004). "Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 291 (14): 1701–1712. doi:10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. PMID 15082697.

- ^ Grodstein F, Clarkson TB, Manson JE (February 2003). "Understanding the divergent data on postmenopausal hormone therapy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (7): 645–650. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb022365. PMID 12584376.

- ^ Vandenbroucke JP (April 2009). "The HRT controversy: observational studies and RCTs fall in line". Lancet. 373 (9671): 1233–1235. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60708-X. PMID 19362661. S2CID 44991220.

- ^ Hsu A, Card A, Lin SX, et al. (December 2009). "Changes in postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy use among women with high cardiovascular risk". American Journal of Public Health. 99 (12): 2184–2187. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.159889. PMC 2775780. PMID 19833984.

- ^ Bell SH, Peck LR (2012). "Obstacles to and limitations of social experiments: 15 false alarms". Abt Thought Leadership Paper Series. Archived from the original on 2018-04-09. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ^ a b c Sanson-Fisher RW, Bonevski B, Green LW, et al. (August 2007). "Limitations of the randomized controlled trial in evaluating population-based health interventions". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 33 (2): 155–161. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.007. PMID 17673104.

- ^ a b Johnston SC, Rootenberg JD, Katrak S, et al. (April 2006). "Effect of a US National Institutes of Health programme of clinical trials on public health and costs". Lancet. 367 (9519): 1319–1327. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68578-4. PMID 16631910. S2CID 41035177.

- ^ a b Yitschaky O, Yitschaky M, Zadik Y (May 2011). "Case report on trial: Do you, Doctor, swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth?". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 5 (1): 179. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-5-179. PMC 3113995. PMID 21569508.

- ^ "How Well Do Meta-Analyses Disclose Conflicts of Interests in Underlying Research Studies | The Cochrane Collaboration". Cochrane.org. Archived from the original on 2014-12-16. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- ^ Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP (2003). "Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review". JAMA. 289 (4): 454–465. doi:10.1001/jama.289.4.454. PMID 12533125.

- ^ a b Bhandari M, Busse JW, Jackowski D, et al. (February 2004). "Association between industry funding and statistically significant pro-industry findings in medical and surgical randomized trials". CMAJ. 170 (4): 477–480. PMC 332713. PMID 14970094. Archived from the original on 2016-08-30. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ Chapman SJ, Shelton B, Mahmood H, et al. (December 2014). "Discontinuation and non-publication of surgical randomised controlled trials: observational study". BMJ. 349 g6870. doi:10.1136/bmj.g6870. PMC 4260649. PMID 25491195.

- ^ Ridker PM, Torres J (May 2006). "Reported outcomes in major cardiovascular clinical trials funded by for-profit and not-for-profit organizations: 2000-2005". JAMA. 295 (19): 2270–2274. doi:10.1001/jama.295.19.2270. PMID 16705108.

- ^ Zhang S, Cao J, Ahn C (August 2010). "Calculating sample size in trials using historical controls". Clinical Trials. 7 (4): 343–353. doi:10.1177/1740774510373629. PMC 3085081. PMID 20573638.

- ^ Deaton A, Cartwright N (August 2018). "Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials". Social Science & Medicine. Randomized Controlled Trials and Evidence-based Policy: A Multidisciplinary Dialogue. 210: 2–21. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.005. PMC 6019115. PMID 29331519.

- ^ Rowland D, DiGuiseppi C, Gross M, et al. (January 2003). "Randomised controlled trial of site specific advice on school travel patterns". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 88 (1): 8–11. doi:10.1136/adc.88.1.8. PMC 1719287. PMID 12495948.

- ^ Graham-Rowe E, Skippon S, Gardner B, et al. (2011). "Can we reduce car use and, if so, how? A review of available evidence". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 44 (5): 401–418. Bibcode:2011TRPA...45..401G. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2011.02.001.

- ^ Melia S (2011). "Do Randomised Control Trials Offer a Solution to 'low Quality' Transport Research?'". Transportation Research Part A. Bristol: University of the West of England.

- ^ a b Farrington DP, Welsh BC (2005). "Randomized experiments in criminology: What have we learned in the last two decades?". Journal of Experimental Criminology. 1 (1): 9–38. doi:10.1007/s11292-004-6460-0. S2CID 145758503.

- ^ Hollin CR (2008). "Evaluating offending behaviour programmes: does only randomization glister?". Criminology and Criminal Justice. 8 (1): 89–106. doi:10.1177/1748895807085871. S2CID 141222135.

- ^ Connolly P, Keenan C, Urbanska K (2018-07-09). "The trials of evidence-based practice in education: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials in education research 1980–2016". Educational Research. 60 (3): 276–291. doi:10.1080/00131881.2018.1493353. ISSN 0013-1881.

- ^ Walker HM, Seeley JR, Small J, et al. (2009). "A randomized controlled trial of the First Step to Success early intervention. Demonstration of program efficacy outcomes in a diverse, urban school district". Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 17 (4): 197–212. doi:10.1177/1063426609341645. S2CID 144571336.

- ^ Bradshaw CP, Zmuda JH, Kellam SG, et al. (November 2009). "Longitudinal Impact of Two Universal Preventive Interventions in First Grade on Educational Outcomes in High School". Journal of Educational Psychology. 101 (4): 926–937. doi:10.1037/a0016586. PMC 3678772. PMID 23766545.

- ^ Krauss A (June 2018). "Why all randomised controlled trials produce biased results". Annals of Medicine. 50 (4): 312–322. doi:10.1080/07853890.2018.1453233. PMID 29616838.

Further reading

[edit]- Bland M (19 March 2008). "Directory of randomisation software and services". University of York.

- Evans I, Thornton H, Chalmers I (2010). Testing treatments: better research for better health care (PDF). London: Pinter & Martin. ISBN 978-1-905177-35-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-25.

- Gelband H (1983). The impact of randomized clinical trials on health policy and medical practice: background paper (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. OTA-BP-H-22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- "REFLECT (Reporting guidElines For randomized controLled trials for livEstoCk and food safeTy) Statement".

- Wathen JK, Cook JD (12 July 2006). "Power and bias in adaptively randomized clinical trials" (PDF). M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas.