Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

525 lines

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

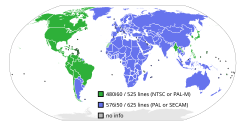

525-line (or EIA 525/60) is an American standard-definition television resolution used since July 1, 1941,[1][2][3] mainly in the context of analog TV broadcast systems. It consists of a 525-line raster, with 486 lines carrying the visible image at 30 (29.97 with color) interlaced frames per second. It was eventually adopted by countries using 60 Hz utility frequency as TV broadcasts resumed after World War II. With the introduction of color television in the 1950s,[4] it became associated with the NTSC analog color standard.

The system was given their letter designation as CCIR System M in the ITU identification scheme adopted in Stockholm in 1961.

A similar 625-line system was adopted by countries using a 50 Hz utility frequency. Other systems, like 375-line, 405-line, 441-line and 819-line existed, but became outdated or had limited adoption.

The modern standard-definition digital video resolution 480i is equivalent to 525-line and can be used to digitize a TV signal, or playback generating a 525-line compatible analog signal.[5]

Analog broadcast television standards

[edit]The following International Telecommunication Union standards use 525-lines:

Analog color television systems

[edit]The following analog television color systems were used in conjunction with the previous standards (identified by a letter after the color system indication):

Digital video

[edit]525-lines is sometimes mentioned when digitizing analog video, or when outputting digital video in a standard definition analog compatible format.

- 480i, a standard-definition television digital video mode.

- NTSC DVD

- NTSC Video CD

- Rec. 601, a 1982 standard for encoding interlaced analog video signals in digital video form.

- D-1, a 1986 SMPTE component digital recording video standard.

- D-2, a 1988 SMPTE composite digital recording video standard.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pursell, Carroll (April 30, 2008). A Companion to American Technology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470695333 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Herbert, Stephen (June 21, 2004). A History of Early Television. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415326681 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Meadow, Charles T. (February 11, 2002). Making Connections: Communication through the Ages. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9781461706915 – via Google Books.

- ^ National Television System Committee (1951–1953), Report and Reports of Panel No. 11, 11-A, 12–19, with Some supplementary references cited in the Reports, and the Petition for adoption of transmission standards for color television before the Federal Communications Commission, n.p., 1953], 17 v. illus., diagrs., tables. 28 cm. LC Control No.:54021386 Library of Congress Online Catalog

- ^ "What means 480i?". Afterdawn.com.

- ^ Parekh, Ranjan (July 1, 2013). Principles of Multimedia. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9781259006500 – via Google Books.

- ^ Poynton, Charles (January 3, 2003). Digital Video and HD: Algorithms and Interfaces. Elsevier. ISBN 9780080504308 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c "Television - Color, Broadcast, CRT | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

525 lines

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and scope

The 525-line television standard, designated as the EIA 525/60 format, refers to an analog raster scanning system that utilizes 525 total horizontal lines per frame, of which 480 lines are visible and carry the active picture information.[6][7] This standard establishes the foundational parameters for electronic monochrome and color television transmission in compatible broadcast environments.[8] The scope of the 525-line standard is confined to analog electronic television systems, particularly those synchronized with 60 Hz alternating current power grids to minimize interference from electrical hum, thereby distinguishing it from earlier mechanical television precursors that employed fewer lines and non-electronic scanning mechanisms such as rotating disks.[9][10] At its core, the raster scanning in the 525-line system operates on a 2:1 interlaced basis, wherein each frame consists of two fields: an odd field scanning lines 1, 3, 5, up to 525, and an even field scanning lines 2, 4, 6, up to 524, effectively doubling the perceived resolution while halving the bandwidth requirements per field.[11] This primary application in the NTSC color encoding system supports broadcast television delivery across compatible regions.[12]Historical significance

The 525-line television standard, adopted by the Federal Communications Commission in 1941, was designed to align closely with the 60 Hz alternating current power frequency prevalent in the Americas and Japan, thereby minimizing visible flicker on cathode-ray tube displays and ensuring stable, interference-free viewing experiences.[5] This synchronization, with a field rate of approximately 59.94 Hz, reduced the impact of power line hum and harmonics, making it particularly suitable for regions with 60 Hz electrical infrastructure.[4] By harmonizing broadcast parameters with local power systems, the standard facilitated widespread consumer adoption without the need for specialized electrical adaptations.[5] Following World War II, the 525-line standard played a pivotal role in the rapid expansion of television broadcasting, transitioning from fewer than 10,000 sets in the United States in 1945 to approximately 6 million by 1950 and over 60 million by 1960, as mass production lowered costs and integrated the medium into households.[13] This growth transformed television into the dominant mass medium, supplanting radio and shaping post-war entertainment and information dissemination across compatible regions. Moreover, the standard served as the foundational framework for the first commercial color television system in the United States, introduced in 1951 and refined for compatibility with existing black-and-white receivers by 1953, allowing seamless upgrades without obsoleting monochrome infrastructure.[14] The 525-line standard demonstrated remarkable longevity, remaining the core analog broadcast format in NTSC-adopting countries for over seven decades until digital transitions began in the late 2000s, such as the full shutdown of over-the-air NTSC signals in the United States by 2021.[15] By the 1980s, it had profoundly impacted global television infrastructure in key markets like North America and Japan and influenced cultural broadcasting norms for generations.[13]Historical development

Early experiments and proposals

In the early 1930s, mechanical television systems, such as John Logie Baird's 240-line setup, demonstrated significant limitations in resolution and scalability, achieving no more than about 240 lines due to the constraints of rotating Nipkow disks and mechanical scanning, which spurred the shift toward fully electronic systems for higher fidelity imaging.[16] During the mid-1930s, major U.S. companies conducted extensive experiments with electronic television. RCA pioneered a 441-line system in 1936, adopting interlaced scanning at 30 frames per second, which became a de facto interim standard for broadcasts and allowed for clearer images than prior mechanical efforts.[17] Philco followed suit in late 1936 with its own 441-line implementation, conducting outdoor transmission tests to refine receiver designs and signal stability.[18] Meanwhile, Allen B. DuMont Laboratories advocated for higher resolutions, proposing a 625-line system in the late 1930s to support improved detail and future-proofing against bandwidth expansions.[19] Key milestones advanced these efforts toward a unified approach. In 1936, the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA) formed a Television Standards Committee that recommended the 441-line framework as a baseline for compatibility across broadcasters.[1] In 1940, Philco increased its experimental resolution to 525 lines, though it advocated for around 605 lines during subsequent standardization debates.[20] These developments culminated in public demonstrations at the 1939 New York World's Fair, where RCA and NBC showcased 441-line electronic television to over 200,000 viewers, broadcasting live events like the fair's opening to highlight the medium's potential despite ongoing debates over line counts.[21] These pre-1941 experiments and rival proposals, including RCA's conservative 441 lines, Philco's and DuMont's ambitions for 605-625 lines, informed the compromises that shaped the eventual 525-line standard approved in 1941.[18]Standardization process

The standardization of the 525-line television system emerged from efforts in the late 1930s and early 1940s to establish a unified U.S. broadcast standard, building on experimental transmissions that dated back to the 1930s.[22] In response to competing proposals from industry leaders, the National Television System Committee (NTSC), formed in 1940 under the sponsorship of the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA) with Federal Communications Commission (FCC) support, recommended a 525-line monochrome system as a compromise between RCA's existing 441-line standard and higher-resolution proposals of around 605 lines advocated by Philco and DuMont.[1] This resolution balanced technical feasibility, image quality, and compatibility with ongoing broadcasts.[23] On April 30, 1941, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved the NTSC's recommendations, formalizing the 525-line, 30 frames-per-second monochrome standard for commercial television.[22] The approval authorized the issuance of the first commercial TV licenses and set July 1, 1941, as the effective date for regular broadcasting under these parameters, marking the official launch of standardized U.S. television service. However, the onset of World War II in December 1941 halted commercial television broadcasting, with regular service resuming only in 1946 after the war.[22] This decision resolved years of regulatory debate and enabled widespread adoption by broadcasters and manufacturers. Subsequent refinements addressed compatibility with emerging technologies. In December 1953, when the FCC approved the compatible color extension to the NTSC system, the frame rate was precisely adjusted from 30 to 29.97 frames per second to prevent interference between the color subcarrier and audio signals in the 4.5 MHz audio band. This offset, calculated as 30/1.001, ensured backward compatibility with monochrome receivers while accommodating the color signal's 3.579545 MHz subcarrier. International recognition followed in the postwar era. During the 1950s, as global television standards proliferated, the 525-line system gained formal designation through the Comité Consultatif International des Radiocommunications (CCIR). At the ITU's 1961 Stockholm conference, it was officially classified as System M, distinguishing it from other line and bandwidth configurations like the 625-line European systems and solidifying its parameters—525 lines, 60 Hz field rate (interlaced), and 6 MHz channel bandwidth—for international reference.[24] This designation facilitated cross-border equipment compatibility and equipment manufacturing standards.Technical specifications

Scanning parameters and frame structure

The 525-line television system utilizes interlaced scanning to form images, dividing each frame into two fields for efficient bandwidth use and reduced flicker. Each field consists of 262.5 scan lines, yielding a total of 525 lines per frame when interlaced at a 2:1 ratio.[25] This structure allows the odd number of lines to ensure proper interleaving between even and odd fields, with the half-line offset facilitating vertical synchronization.[26] The nominal field rate is 60 fields per second, corresponding to a frame rate of 30 frames per second in the original monochrome specification, aligned with the 60 Hz power line frequency to minimize interference.[1] Accounting for vertical blanking intervals used for synchronization and retrace, the active picture area encompasses 485 to 488 visible lines per frame, providing the effective vertical resolution for image content.[27] The standard aspect ratio is 4:3, defining the proportional relationship between the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the scanned image.[25] Horizontal resolution is approximately 440 television lines (TVL), a measure of the system's ability to resolve fine horizontal details, limited by the overall signal design to match vertical capabilities roughly equivalently.[28] In the color variant, the frame rate is adjusted slightly to 29.97 frames per second to avoid beat interference with the audio carrier.[25]Signal characteristics and bandwidth

The 525-line television signal, as defined in early NTSC specifications, utilizes a composite video waveform that combines luminance information with synchronization pulses. The full composite signal amplitude measures 1.0 volt peak-to-peak, with the luminance portion (from blanking level to peak white) spanning approximately 0.7 volts and the synchronization pulses adding the remaining 0.3 volts. Blanking level is established at 0 IRE units, reference white at 100 IRE, setup (black level) at 7.5 IRE, and sync tips at -40 IRE, ensuring compatibility with monochrome transmission while accommodating the 525 total scan lines per frame.[29][30] The luminance signal, representing brightness variations, occupies a bandwidth of 4.2 MHz in the monochrome configuration, providing sufficient resolution for the system's horizontal detail without exceeding transmission limits. This bandwidth is achieved through amplitude modulation of the picture carrier, with negative polarity such that increased light intensity reduces carrier amplitude. Channel spacing for broadcast transmission extends to 6 MHz to encompass the full signal spectrum, including audio and guard bands.[29][31] Transmission employs vestigial sideband (VSB) amplitude modulation within the 6 MHz channel to optimize spectrum efficiency. The lower sideband is partially attenuated, retaining only a vestige up to 1.25 MHz below the carrier frequency, while the upper sideband extends fully to 4.2 MHz above it; this configuration minimizes interference in adjacent channels while preserving signal integrity. The picture carrier is positioned 1.25 MHz above the channel's lower boundary, facilitating the VSB filtering process.[31][8]Color encoding methods

The NTSC color television system, adopted in 1953, introduced color to the existing 525-line monochrome framework by encoding chrominance information within the luminance signal using the YIQ color space. In this model, the Y component represents luminance, derived as , while the I (in-phase) and Q (quadrature) components capture chrominance, with formulas and , where R, G, and B are the red, green, and blue primaries.[32][31] These chrominance signals modulate a 3.579545 MHz subcarrier through quadrature amplitude modulation, where I and Q are phase-shifted by 90 degrees relative to each other and combined into a single chrominance signal added to the Y signal.[32][31] The subcarrier frequency, precisely 455 times half the horizontal line frequency, was selected to interleave color information with luminance details, minimizing visible interference while fitting within the 6 MHz channel bandwidth; the I signal has a bandwidth of about 1.5 MHz, and Q is limited to 0.6 MHz for reduced complexity.[32][33] Backward compatibility with monochrome receivers was a core design principle, achieved by transmitting the full-bandwidth Y signal, which black-and-white sets could interpret directly as a grayscale image, while color information was suppressed during monochrome broadcasts via a "color killer" circuit.[32][31] To enable accurate demodulation in color receivers, a color burst—a short, unmodulated 3.579545 MHz sine wave of 8 to 10 cycles—is inserted on the back porch of each horizontal synchronizing pulse, providing a phase reference that synchronizes the local oscillator to the transmitted subcarrier phase (defined as ).[32][31] This burst is omitted during equalizing pulses or monochrome transmissions to avoid artifacts, ensuring seamless operation across mixed broadcast environments.[31] The system's adoption necessitated a slight adjustment to the frame rate from 30 to 29.97 fps to derive the subcarrier precisely from the audio carrier offset.[32] Despite these innovations, the NTSC color encoding exhibited limitations, particularly susceptibility to hue errors arising from subcarrier phase distortions during transmission or processing.[32][33] Nonlinearities in amplifiers or kinescopes could cause differential phase shifts, manifesting as incorrect color tints, such as purplish casts or unnatural skin tones; audience surveys reported such color inaccuracies in about 5% of responses.[32] Subcarrier interference with luminance led to cross-color artifacts, like rainbow patterns on fine details, and cross-luminance effects, such as "hanging dots," due to spectral overlap in the shared bandwidth; these were exacerbated by high-resolution sources and required comb filtering in receivers for mitigation, though not always fully resolved.[33] Additional challenges included color bleeding and fringing from adjacent channel interference, reducing effective signal-to-noise ratios by 6-8 dB compared to monochrome.[32]Regional implementations and variants

NTSC in North America

The NTSC television standard, utilizing 525 scan lines, served as the foundational analog broadcast system across North America, encompassing the United States, Canada, and Mexico, where it supported both black-and-white and later color transmissions until the shift to digital formats.[1] This implementation emphasized compatibility and regulatory uniformity to foster widespread adoption among broadcasters and consumers in the region.[34] In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) enforced the initial NTSC standard for black-and-white television in March 1941, with commercial operations authorized to commence on July 1 of that year, marking the beginning of regulated over-the-air broadcasting.[34][35] The transition to color occurred through a backward-compatible enhancement to this framework, with major networks driving adoption: NBC initiated extensive color programming in November 1960, followed by CBS and ABC, achieving near-complete color primetime schedules across all three by the 1965–1966 season.[36][37] Channel allocations for NTSC broadcasts in North America were structured to optimize spectrum use, assigning VHF frequencies to channels 2–13 (with low-band 2–6 and high-band 7–13) and UHF to channels 14–83, each separated by 6 MHz to accommodate the signal's bandwidth requirements.[38][39] A notable adaptation for accessibility was the integration of closed captioning on Line 21 of the vertical blanking interval, reserved by the FCC in December 1976 following petitions from public broadcasters, which enabled the encoding of text data for real-time display on compatible decoders starting in the late 1970s.[40][41]NTSC-J and other Asian variants

NTSC-J, the variant of the 525-line standard adopted in Japan in 1953, incorporated a modified color subcarrier frequency of 4.433619 MHz to improve stability using quartz crystal oscillators, diverging from the standard NTSC-M subcarrier while maintaining overall compatibility with monochrome receivers.[42] This adjustment facilitated more precise signal generation in consumer electronics manufacturing, aligning with Japan's emphasis on high-volume production of reliable television sets.[42] The NTSC standard, including its Japanese adaptation, was employed in other Asian regions such as the Philippines, where television broadcasting began in 1953 using NTSC for both black-and-white and color transmissions starting in 1966, and South Korea, where it served as the basis for broadcasts from 1956 until the full rollout of color in 1980 marked a significant shift in the 1980s.[43] In South Korea, the transition to widespread color adoption during this period reflected economic growth and infrastructure development, with NTSC remaining the core system until digital migration in the 2010s.[44] Hardware implementations for NTSC-J emphasized adaptations to Japan's electrical infrastructure, including compatibility with 100 V and 60 Hz power supplies—though eastern regions operate at 50 Hz, dual-frequency designs ensured nationwide usability—and narrower tolerances in video tape recorders (VTRs) to account for precise tape head alignment and reduced jitter in high-density recording formats prevalent in Asian consumer markets.[45] These modifications supported the integration of NTSC-J with local appliances, minimizing interference from power fluctuations while enabling compact, cost-effective VTR designs for home use.[45]PAL-M and South American adaptations

PAL-M is a hybrid analog color television system that combines the 525-line, 60 Hz scanning parameters of the NTSC System M with the phase alternation by line (PAL) color encoding technique. This adaptation was specifically developed for Brazil in the early 1970s to provide improved color stability over NTSC by alternating the phase of the color subcarrier on alternate lines, reducing hue errors caused by transmission phase shifts.[46] The system employs a 4-field sequence for color synchronization, where the V-axis (blue-minus-red) reference signal inverts every other line and every other field, ensuring consistent color reproduction.[46] Brazil adopted PAL-M in 1972 under its military government, marking the country as the first in South America to implement regular color broadcasts on March 31 of that year. The choice stemmed from dissatisfaction with NTSC's color inconsistencies and the incompatibility of standard 625-line PAL with Brazil's existing monochrome infrastructure, which was based on the 525-line System M imported from the United States.[47] By retaining the 60 Hz field rate and 525 lines per frame, PAL-M maintained backward compatibility with black-and-white receivers while incorporating PAL's superior color handling. The color subcarrier frequency was set at 3.575611 MHz, closely aligned with NTSC's 3.579545 MHz to minimize bandwidth adjustments in existing transmission equipment.[46] In neighboring countries, similar adaptations emerged to address regional power grid differences and equipment availability, though they diverged from the 525-line framework. Argentina and Uruguay adopted PAL-N in the mid-1970s and early 1980s, respectively, a variant using 625 lines at 50 Hz with a subcarrier frequency of approximately 3.582 MHz and the same 4-field PAL sequence for color encoding. This system provided better vertical resolution but required separate infrastructure from North American NTSC imports.[48] Paraguay followed suit with PAL-N, prioritizing compatibility with European PAL technology over U.S. NTSC standards. These choices reflected South America's fragmented adoption patterns, influenced by 50 Hz electrical systems in the Southern Cone.[47] The implementation of PAL-M in Brazil presented significant challenges, particularly in equipment compatibility and importation. As a non-standard hybrid, it was incompatible with off-the-shelf NTSC color televisions and production gear from the United States, leading to import conflicts and the need for custom manufacturing or modifications. This reliance on specialized local or European suppliers increased costs and delayed widespread rollout, necessitating substantial government investment in national television infrastructure to support the standard.[47] Despite these hurdles, PAL-M enabled Brazil to achieve high color TV penetration by the 1980s, fostering domestic broadcasting growth.Adoption and applications

Countries and broadcast networks

The 525-line television standard, encompassing variants such as NTSC-M and PAL-M, was adopted as the primary analog broadcast format in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, Brazil, and more than 20 Caribbean nations and territories, including Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago.[49][50] These countries represented the core of global 525-line implementation, spanning North America, parts of South America, East Asia, and the Caribbean region, where the standard facilitated compatibility with 60 Hz electrical grids and supported early television expansion.[51] In the United States, the "Big Three" networks—NBC, CBS, and ABC—drove the standard's adoption and dominated national broadcasting. NBC launched regular experimental television broadcasts on April 30, 1939, coinciding with the New York World's Fair opening and marking the onset of scheduled programming under early 525-line specifications.[52] CBS and ABC followed with commercial operations in 1941 and 1948, respectively, solidifying the networks' role in standardizing 525-line transmissions across the country.[53] Japan's public broadcaster NHK initiated television service on February 1, 1953, using the NTSC-J variant of the 525-line system, which quickly expanded to cover major urban areas and supported the nation's postwar media growth.[54] In Brazil, Rede Globo, founded on April 26, 1965, adopted the 525-line framework from the outset, transitioning to the PAL-M color encoding in 1972 while maintaining the line count and 60 Hz field rate for compatibility with imported equipment.[55][56] In the U.S., hundreds of commercial stations operated under this standard, underscoring its scale and institutional entrenchment.Consumer and professional usage

In consumer applications, cathode ray tube (CRT) televisions were the primary display devices for 525-line analog broadcasts from their commercial introduction in the early 1940s until the widespread adoption of flat-panel alternatives in the 2000s.[16][57] These sets decoded the interlaced 525-line signal at 60 fields per second, providing standard-definition viewing for home entertainment, with resolutions effectively around 480 visible lines after accounting for overscan and blanking intervals.[1] Video cassette recorders (VCRs) based on the VHS format were fully compatible with the 525-line NTSC standard, enabling consumers to record and playback broadcasts on cassettes that supported up to 3 hours of footage at standard play (SP) speed for optimal quality.[58] This compatibility facilitated time-shifting of television content, with VHS tapes capturing the full 525-line frame structure while adhering to NTSC color encoding.[59] Professionally, 525-line systems were integral to broadcast production, with studio and field cameras such as the Ikegami HL-79 series employed for electronic news gathering (ENG) and electronic field production (EFP) from the late 1970s onward.[60] The Ikegami HL-79, featuring three 2/3-inch plumbicon pickup tubes, generated high-quality 525-line/60-field NTSC signals suitable for live transmission and studio workflows, noted for its portability and automatic iris control. In post-production, film-to-video transfers were routinely performed at 525-line resolution to align cinematic content with the NTSC broadcast standard, ensuring seamless integration into television programming without resolution mismatch.[1] Accessories like RF modulators allowed connection of non-RF video sources, such as VCRs or early game consoles, to 525-line CRT televisions by converting composite signals to VHF/UHF channels compatible with NTSC tuning.[61] Antenna designs for reception varied by environment; urban areas often relied on compact indoor or combined VHF/UHF antennas for reliable signal capture from nearby transmitters, while rural or fringe locations required directional outdoor antennas or separate VHF and UHF models to overcome distance-related signal attenuation.[62]Transition to digital

Analog phase-out timelines

The phase-out of analog 525-line television broadcasting, primarily associated with the NTSC standard, occurred progressively across adopting countries as part of the global transition to digital terrestrial television (DTT). This process involved mandated shutdowns of over-the-air analog signals to enable more efficient spectrum use and improved broadcast quality. Key nations using 525-line systems completed their transitions between 2009 and 2025, with variations due to national regulations and infrastructure readiness. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) required all full-power analog television stations to cease broadcasting on June 12, 2009, marking the end of widespread NTSC analog transmissions. This date followed a delay from an original February 17, 2009, target, allowing additional time for consumer preparation through converter box subsidies and public awareness campaigns. Low-power and Class A stations had until later dates, with full compliance achieved by 2015. In Mexico, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT) mandated a national analog shutdown on December 31, 2015, following phased transitions in border regions starting in 2013. This completed the switchover for all 99 television markets, with subsidies provided for digital set-top boxes to households without digital receivers.[63] Canada's analog shutdown was coordinated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), which set August 31, 2011, as the mandatory transition date for over-the-air signals in major markets. This applied to 32 communities, including major cities like Toronto and Vancouver, though some low-power and remote transmitters continued analog operations until 2012 or later to serve isolated areas. Japan's Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications enforced a nationwide analog termination on July 24, 2011, except in disaster-affected regions like Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima, where signals were extended until March 31, 2012, due to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. In South Korea, the Korea Communications Commission (KCC) set December 31, 2012, as the nationwide analog shutdown date, ending 56 years of NTSC broadcasting. The transition included public campaigns and subsidies for digital TVs, achieving full digital coverage.[64] Brazil, using the PAL-M variant of the 525-line system, adopted a phased approach to analog shutdown under the Ministry of Communications. Initial phases targeted major cities starting in 2017, with partial completion by 2023 covering over 80% of the population; extensions pushed the final nationwide cutoff, which was completed on June 30, 2025, for remaining municipalities lacking full digital infrastructure. This delay accommodated socioeconomic factors, including the distribution of set-top boxes to low-income households.[65][66] The primary drivers for these phase-outs included the reallocation of broadcast spectrum to mobile broadband and public safety services, as analog signals inefficiently occupied 6 MHz channels per station while digital allowed multiplexing multiple channels in the same bandwidth. In the U.S., for instance, the transition freed 108 MHz of spectrum auctioned for wireless uses, generating over $18 billion in revenue. Digital efficiency also enhanced picture quality and enabled high-definition broadcasting without additional spectrum demands. These changes impacted over-the-air viewers, with approximately 12% of U.S. households relying solely on antennas in 2009, though over 90% of total households were unaffected due to prior adoption of cable, satellite, or digital-ready equipment.| Country | Shutdown Date (Major Markets) | Key Authority | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | June 12, 2009 | FCC | Full-power stations; low-power extended to 2015 |

| Mexico | December 31, 2015 | IFT | Phased from 2013; national completion |

| Canada | August 31, 2011 | CRTC | 32 markets; some low-power continued post-2011 |

| Japan | July 24, 2011 | MIC | Excluded disaster areas until 2012 |

| South Korea | December 31, 2012 | KCC | Nationwide; end of NTSC broadcasting |

| Brazil | Phased; completed June 30, 2025 | Ministry of Communications | Partial by 2023; set-top box program for accessibility |