Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pulse-code modulation

View on Wikipedia

| Pulse-code modulation | |

|---|---|

| Filename extension |

.L16, .WAV, .AIFF, .AU, .PCM[1] |

| Internet media type | |

| Type code | "AIFF" for L16,[1] none[3] |

| Magic number | Varies |

| Type of format | Uncompressed audio |

| Contained by | Audio CD, AES3, WAV, AIFF, AU, M2TS, VOB, and many others |

| Open format? | Yes |

| Free format? | Yes[5] |

| Passband modulation |

|---|

|

| Analog modulation |

| Digital modulation |

| Hierarchical modulation |

| Spread spectrum |

| See also |

Pulse-code modulation (PCM) is a method used to digitally represent analog signals. It is the standard form of digital audio in computers, compact discs, digital telephony and other digital audio applications. In a PCM stream, the amplitude of the analog signal is sampled at uniform intervals, and each sample is quantized to the nearest value within a range of digital steps. Shannon, Oliver, and Pierce were inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for their PCM patent granted in 1952.[6][7][8]

Linear pulse-code modulation (LPCM) is a specific type of PCM in which the quantization levels are linearly uniform.[5] This is in contrast to PCM encodings in which quantization levels vary as a function of amplitude (as with the A-law algorithm or the μ-law algorithm). Though PCM is a more general term, it is often used to describe data encoded as LPCM.

A PCM stream has two basic properties that determine the stream's fidelity to the original analog signal: the sampling rate, which is the number of times per second that samples are taken; and the bit depth, which determines the number of possible digital values that can be used to represent each sample.

History

[edit]Early electrical communications started to sample signals in order to multiplex samples from multiple telegraphy sources and to convey them over a single telegraph cable. The American inventor Moses G. Farmer conceived telegraph time-division multiplexing (TDM) as early as 1853. Electrical engineer W. M. Miner, in 1903, used an electro-mechanical commutator for time-division multiplexing multiple telegraph signals; he also applied this technology to telephony. He obtained intelligible speech from channels sampled at a rate above 3500–4300 Hz; lower rates proved unsatisfactory.

In 1920, the Bartlane cable picture transmission system used telegraph signaling of characters punched in paper tape to send samples of images quantized to 5 levels.[9] In 1926, Paul M. Rainey of Western Electric patented a facsimile machine that transmitted its signal using 5-bit PCM, encoded by an opto-mechanical analog-to-digital converter.[10] The machine did not go into production.[11]

British engineer Alec Reeves, unaware of previous work, conceived the use of PCM for voice communication in 1937 while working for International Telephone and Telegraph in France. He described the theory and its advantages, but no practical application resulted. Reeves filed for a French patent in 1938, and his US patent was granted in 1943.[12] By this time Reeves had started working at the Telecommunications Research Establishment.[11]

The first transmission of speech by digital techniques, the SIGSALY encryption equipment, conveyed high-level Allied communications during World War II. In 1949, for the Canadian Navy's DATAR system, Ferranti Canada built a working PCM radio system that was able to transmit digitized radar data over long distances.[13]

PCM in the late 1940s and early 1950s used a cathode-ray coding tube with a plate electrode having encoding perforations.[14] As in an oscilloscope, the beam was swept horizontally at the sample rate while the vertical deflection was controlled by the input analog signal, causing the beam to pass through higher or lower portions of the perforated plate. The plate collected or passed the beam, producing current variations in binary code, one bit at a time. Rather than natural binary, the grid of Goodall's later tube was perforated to produce a glitch-free Gray code and produced all bits simultaneously by using a fan beam instead of a scanning beam.[15]

In the United States, the National Inventors Hall of Fame has honored Bernard M. Oliver[16] and Claude Shannon[17] as the inventors of PCM,[18] as described in "Communication System Employing Pulse Code Modulation", U.S. patent 2,801,281 filed in 1946 and 1952, granted in 1956. Another patent by the same title was filed by John R. Pierce in 1945, and issued in 1948: U.S. patent 2,437,707. The three of them published "The Philosophy of PCM" in 1948.[19]

The T-carrier system, introduced in 1961, uses two twisted-pair transmission lines to carry 24 PCM telephone calls sampled at 8 kHz and 8-bit resolution. This development improved capacity and call quality compared to the previous frequency-division multiplexing schemes.

In 1973, adaptive differential pulse-code modulation (ADPCM) was developed, by P. Cummiskey, Nikil Jayant and James L. Flanagan.[20]

Digital audio recordings

[edit]In 1967, the first PCM recorder was developed by NHK's research facilities in Japan.[21] The 30 kHz 12-bit device used a compander (similar to DBX Noise Reduction) to extend the dynamic range, and stored the signals on a video tape recorder. In 1969, NHK expanded the system's capabilities to 2-channel stereo and 32 kHz 13-bit resolution. In January 1971, using NHK's PCM recording system, engineers at Denon recorded the first commercial digital recordings.[note 1][21]

In 1972, Denon unveiled the first 8-channel digital recorder, the DN-023R, which used a 4-head open reel broadcast video tape recorder to record in 47.25 kHz, 13-bit PCM audio.[note 2] In 1977, Denon developed the portable PCM recording system, the DN-034R. Like the DN-023R, it recorded 8 channels at 47.25 kHz, but it used 14-bits "with emphasis, making it equivalent to 15.5 bits."[21]

In 1979, the first digital pop album, Bop till You Drop, was recorded. It was recorded in 50 kHz, 16-bit linear PCM using a 3M digital tape recorder.[22]

The compact disc (CD) brought PCM to consumer audio applications with its introduction in 1982. The CD uses a 44,100 Hz sampling frequency and 16-bit resolution and stores up to 80 minutes of stereo audio per disc.

Digital telephony

[edit]The rapid development and wide adoption of PCM digital telephony was enabled by metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) switched capacitor (SC) circuit technology, developed in the early 1970s.[23] This led to the development of PCM codec-filter chips in the late 1970s.[23][24] The silicon-gate CMOS (complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by David A. Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980,[23] has since been the industry standard for digital telephony.[23][24] By the 1990s, telecommunication networks such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN) had been largely digitized with very-large-scale integration (VLSI) CMOS PCM codec-filters, widely used in electronic switching systems for telephone exchanges, user-end modems and a wide range of digital transmission applications such as the integrated services digital network (ISDN), cordless telephones and cell phones.[24]

Implementations

[edit]PCM is the method of encoding typically used for uncompressed digital audio.[note 3]

- The 4ESS switch introduced time-division switching into the US telephone system in 1976, based on medium scale integrated circuit technology.[25]

- LPCM is used for the lossless encoding of audio data in the compact disc Red Book standard (informally also known as Audio CD), introduced in 1982.

- AES3 (specified in 1985, upon which S/PDIF is based) is a particular format using LPCM.

- LaserDiscs with digital sound have an LPCM track on the digital channel.

- On PCs, PCM and LPCM often refer to the format used in WAV (defined in 1991) and AIFF audio container formats (defined in 1988). LPCM data may also be stored in other formats such as AU, raw audio format (header-less file) and various multimedia container formats.

- LPCM has been defined as a part of the DVD (since 1995) and Blu-ray (since 2006) standards.[26][27][28] It is also defined as a part of various digital video and audio storage formats (e.g. DV since 1995,[29] AVCHD since 2006[30]).

- LPCM is used by HDMI (defined in 2002), a single-cable digital audio/video connector interface for transmitting uncompressed digital data.

- RF64 container format (defined in 2007) uses LPCM and also allows non-PCM bitstream storage: various compression formats contained in the RF64 file as data bursts (Dolby E, Dolby AC3, DTS, MPEG-1/MPEG-2 Audio) can be "disguised" as PCM linear.[31]

Modulation

[edit]

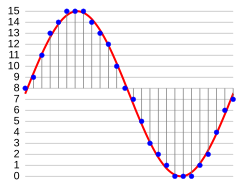

In the diagram, a sine wave (red curve) is sampled and quantized for PCM. The sine wave is sampled at regular intervals, shown as vertical lines. For each sample, one of the available values (on the y-axis) is chosen. The PCM process is commonly implemented on a single integrated circuit called an analog-to-digital converter (ADC). This produces a fully discrete representation of the input signal (blue points) that can be easily encoded as digital data for storage or manipulation. Several PCM streams could also be multiplexed into a larger aggregate data stream, generally for transmission of multiple streams over a single physical link. One technique is called time-division multiplexing (TDM) and is widely used, notably in the modern public telephone system.

Demodulation

[edit]The electronics involved in producing an accurate analog signal from the discrete data are similar to those used for generating the digital signal. These devices are digital-to-analog converters (DACs). They produce a voltage or current (depending on type) that represents the value presented on their digital inputs. This output would then generally be filtered and amplified for use.

To recover the original signal from the sampled data, a demodulator can apply the procedure of modulation in reverse. After each sampling period, the demodulator reads the next value and transitions the output signal to the new value. As a result of these transitions, the signal retains a significant amount of high-frequency energy due to imaging effects. To remove these undesirable frequencies, the demodulator passes the signal through a reconstruction filter that suppresses energy outside the expected frequency range (greater than the Nyquist frequency ).[note 4]

Standard sampling precision and rates

[edit]Common sample depths for LPCM are 8, 16, 20 or 24 bits per sample.[1][2][3][32]

LPCM encodes a single sound channel. Support for multichannel audio depends on file format and relies on synchronization of multiple LPCM streams.[5][33] While two channels (stereo) is the most common format, systems can support up to 8 audio channels (7.1 surround)[2][3] or more.

Common sampling frequencies are 48 kHz as used with DVD format videos, or 44.1 kHz as used in CDs. Sampling frequencies of 96 kHz or 192 kHz can be used on some equipment, but the benefits have been debated.[34]

Limitations

[edit]The Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem shows PCM devices can operate without introducing distortions within their designed frequency bands if they provide a sampling frequency at least twice that of the highest frequency contained in the input signal. For example, in telephony, the usable voice frequency band ranges from approximately 300 to 3400 Hz.[35] For effective reconstruction of the voice signal, telephony applications therefore typically use an 8000 Hz sampling frequency which is more than twice the highest usable voice frequency.

Regardless, there are potential sources of impairment implicit in any PCM system:

- Choosing a discrete value that is near but not exactly at the analog signal level for each sample leads to quantization error. When dithering is used to compensate for this, it introduces additional noise.[note 5]

- Between samples no measurement of the signal is made; the sampling theorem guarantees non-ambiguous representation and recovery of the signal only if it has no energy at frequency fs/2 or higher (one half the sampling frequency, known as the Nyquist frequency); higher frequencies will not be correctly represented or recovered and add aliasing distortion to the signal below the Nyquist frequency.

- As samples are dependent on time, an accurate clock is required for accurate reproduction. If either the encoding or decoding clock is not stable, these imperfections will directly affect the output quality of the device.[note 6]

Processing and coding

[edit]Some forms of PCM combine signal processing with coding. Older versions of these systems applied the processing in the analog domain as part of the analog-to-digital process; newer implementations do so in the digital domain. These simple techniques have been largely rendered obsolete by modern transform-based audio compression techniques, such as modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) coding.

- Linear PCM (LPCM) is PCM with linear quantization.[5]

- Differential PCM (DPCM) encodes the PCM values as differences between the current and the predicted value. An algorithm predicts the next sample based on the previous samples, and the encoder stores only the difference between this prediction and the actual value. If the prediction is reasonable, fewer bits can be used to represent the same information. For audio, this type of encoding reduces the number of bits required per sample by about 25% compared to PCM.

- Adaptive differential pulse-code modulation (ADPCM) is a variant of DPCM that varies the size of the quantization step, to allow further reduction of the required bandwidth for a given signal-to-noise ratio.

- Delta modulation is a form of DPCM that uses one bit per sample to indicate whether the signal is increasing or decreasing compared to the previous sample.

In telephony, a standard audio signal for a single phone call is encoded as 8,000 samples per second, of 8 bits each, giving a 64 kbit/s digital signal known as DS0. The default signal compression encoding on a DS0 is either μ-law (mu-law) PCM (North America and Japan) or A-law PCM (Europe and most of the rest of the world). These are logarithmic compression systems where a 12- or 13-bit linear PCM sample number is mapped into an 8-bit value. This system is described by international standard G.711.

Where circuit costs are high and loss of voice quality is acceptable, it sometimes makes sense to compress the voice signal even further. An ADPCM algorithm is used to map a series of 8-bit μ-law or A-law PCM samples into a series of 4-bit ADPCM samples. In this way, the capacity of the line is doubled. The technique is detailed in the G.726 standard.

Audio coding formats and audio codecs have been developed to achieve further compression. Some of these techniques have been standardized and patented. Advanced compression techniques, such as modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) and linear predictive coding (LPC), are now widely used in mobile phones, voice over IP (VoIP) and streaming media.

Encoding for serial transmission

[edit]PCM can be either return-to-zero (RZ) or non-return-to-zero (NRZ). For a NRZ system to be synchronized using in-band information, there must not be long sequences of identical symbols, such as ones or zeroes. For binary PCM systems, the density of 1-symbols is called ones-density.[36]

Ones-density is often controlled using precoding techniques such as run-length limited encoding, where the PCM code is expanded into a slightly longer code with a guaranteed bound on ones-density before modulation into the channel. In other cases, extra framing bits are added into the stream, which guarantees at least occasional symbol transitions.

Another technique used to control ones-density is the use of a scrambler on the data, which will tend to turn the data stream into a stream that looks pseudo-random, but where the data can be recovered exactly by a complementary descrambler. In this case, long runs of zeroes or ones are still possible on the output but are considered unlikely enough to allow reliable synchronization.

In other cases, the long term DC value of the modulated signal is important, as building up a DC bias will tend to move communications circuits out of their operating range. In this case, special measures are taken to keep a count of the cumulative DC bias and to modify the codes if necessary to make the DC bias always tend back to zero.

Many of these codes are bipolar codes, where the pulses can be positive, negative or absent. In the typical alternate mark inversion code, non-zero pulses alternate between being positive and negative. These rules may be violated to generate special symbols used for framing or other special purposes.

Nomenclature

[edit]The word pulse in the term pulse-code modulation refers to the pulses to be found in the transmission line. This perhaps is a natural consequence of this technique having evolved alongside two analog methods, pulse-width modulation and pulse-position modulation, in which the information to be encoded is represented by discrete signal pulses of varying width or position, respectively.[citation needed] In this respect, PCM bears little resemblance to these other forms of signal encoding, except that all can be used in time-division multiplexing, and the numbers of the PCM codes are represented as electrical pulses.

See also

[edit]- Beta encoder

- Equivalent pulse code modulation noise

- Signal-to-quantization-noise ratio (SQNR), one method of measuring quantization error

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Among the first recordings was Uzu: The World Of Stomu Yamash'ta 2 by Stomu Yamashta.

- ^ The first recording with this new system was recorded in Tokyo during April 24–26, 1972.

- ^ Other methods exist such as pulse-density modulation used also on Super Audio CD.

- ^ Some systems use digital filtering to remove some of the aliasing, converting the signal from digital to analog at a higher sample rate such that the analog anti-aliasing filter is much simpler. In some systems, no explicit filtering is done at all; as it is impossible for any system to reproduce a signal with infinite bandwidth, inherent losses in the system compensate for the artifacts — or the system simply does not require much precision.

- ^ Quantization error swings between -q/2 and q/2. In the ideal case (with a fully linear ADC and signal level >> q) it is uniformly distributed over this interval, with zero mean and variance of q2/12.

- ^ A slight difference between the encoding and decoding clock frequencies is not generally a major concern; a small constant error is not noticeable. Clock error does become a major issue if the clock contains significant jitter, however.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Alvestrand, Harald Tveit; Salsman, James (May 1999). "RFC 2586 – The Audio/L16 MIME content type". The Internet Society. doi:10.17487/RFC2586. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c Casner, S. (March 2007). "RFC 4856 – Media Type Registration of Payload Formats in the RTP Profile for Audio and Video Conferences – Registration of Media Type audio/L8". The IETF Trust. doi:10.17487/RFC4856. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d Bormann, C.; Casner, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Ogawa, A. (January 2002). "RFC 3190 – RTP Payload Format for 12-bit DAT Audio and 20- and 24-bit Linear Sampled Audio". The Internet Society. doi:10.17487/RFC3190. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Audio Media Types". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Linear Pulse Code Modulated Audio (LPCM)". Library of Congress. April 19, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Noll, A. Michael (1997). Highway of Dreams: A Critical View Along the Information Superhighway. Telecommunications (Revised ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8058-2557-2.

- ^ Leibson, Steven (September 7, 2021). "A Brief History of the Single-Chip DSP, Part I". EEJournal. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ Barrett, G. Douglas (2023). Experimenting the Human: Art, Music, and the Contemporary Posthuman. Chicago London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-226-82340-9.

- ^ "The Bartlane Transmission System". DigicamHistory.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ U.S. patent number 1,608,527; also see p. 8, Data conversion handbook, Walter Allan Kester, ed., Newnes, 2005, ISBN 0-7506-7841-0.

- ^ a b John Vardalas (June 2013), Pulse Code Modulation: It all Started 75 Years Ago with Alec Reeves, IEEE

- ^ US 2272070

- ^ Porter, Arthur (2004). So Many Hills to Climb. Beckham Publications Group. ISBN 9780931761188.[page needed]

- ^ Sears, R. W. (January 1948). "Electron Beam Deflection Tube for Pulse Code Modulation". Bell System Technical Journal. 27. Bell Labs: 44–57. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01330.x. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Goodall, W. M. (January 1951). "Television by Pulse Code Modulation". Bell System Technical Journal. 30. Bell Labs: 33–49. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1951.tb01365.x. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ "Bernard Oliver". National Inventor's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ "Claude Shannon". National Inventor's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 6, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame announces 2004 class of inventors". Science Blog. February 11, 2004. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ B. M. Oliver; J. R. Pierce & C. E. Shannon (November 1948). "The Philosophy of PCM". Proceedings of the IRE. 36 (11): 1324–1331. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1948.231941. ISSN 0096-8390. S2CID 51663786.

- ^ P. Cummiskey, N. S. Jayant, and J. L. Flanagan, "Adaptive quantization in differential PCM coding of speech," Bell Syst. Tech. J., vol. 52, pp. 1105–1118, Sept. 1973.

- ^ a b c Thomas Fine (2008). "The dawn of commercial digital recording" (PDF). ARSC Journal. 39 (1): 1–17.

- ^ Roger Nichols. "I Can't Keep Up With All The Formats II". Archived from the original on October 20, 2002.

The Ry Cooder Bop Till You Drop album was the first digitally recorded pop album

- ^ a b c d Allstot, David J. (2016). "Switched Capacitor Filters" (PDF). In Maloberti, Franco; Davies, Anthony C. (eds.). A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing. IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. pp. 105–110. ISBN 9788793609860. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c Floyd, Michael D.; Hillman, Garth D. (October 8, 2018) [1st pub. 2000]. "Pulse-Code Modulation Codec-Filters". The Communications Handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 26–1, 26–2, 26–3. ISBN 9781420041163.

- ^ Cambron, G. Keith (October 17, 2012). Global Networks: Engineering, Operations and Design. John Wiley & Sons. p. 345.

- ^ Blu-ray Disc Association (March 2005), White paper Blu-ray Disc Format – 2.B Audio Visual Application Format Specifications for BD-ROM (PDF), retrieved July 26, 2009

- ^ "DVD Technical Notes (DVD Video – "Book B") – Audio data specifications". July 21, 1996. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ^ Jim Taylor. "DVD Frequently Asked Questions (and Answers) – Audio details of DVD-Video". Retrieved March 20, 2010.

- ^ "How DV works". Archived from the original on December 6, 2007. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ "AVCHD Information Website – AVCHD format specification overview". Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ^ EBU (July 2009), EBU Tech 3306 – MBWF / RF64: An Extended File Format for Audio (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009, retrieved January 19, 2010

- ^ Mostafa, Mohamed; Kumar, Rajesh (May 2001). "RFC 3108 – Conventions for the use of the Session Description Protocol (SDP) for ATM Bearer Connections". doi:10.17487/RFC3108. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "PCM, Pulse Code Modulated Audio". Library of Congress. April 6, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Christopher, Montgometry. "24/192 Music Downloads, and why they do not make sense". Chris "Monty" Montgomery. Archived from the original on September 6, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ^ https://www.its.bldrdoc.gov/fs-1037/dir-039/_5829.htm[failed verification]

- ^ Stallings, William, Digital Signaling Techniques, December 1984, Vol. 22, No. 12, IEEE Communications Magazine

Further reading

[edit]- Franklin S. Cooper; Ignatius Mattingly (1969). "Computer-controlled PCM system for investigation of dichotic speech perception". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 46 (1A): 115. Bibcode:1969ASAJ...46..115C. doi:10.1121/1.1972688.

- Ken C. Pohlmann (1985). Principles of Digital Audio (2nd ed.). Carmel, Indiana: Sams/Prentice-Hall Computer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-672-22634-2.

- D. H. Whalen, E. R. Wiley, Philip E. Rubin, and Franklin S. Cooper (1990). "The Haskins Laboratories pulse code modulation (PCM) system". Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 22 (6): 550–559. doi:10.3758/BF03204440.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bill Waggener (1995). Pulse Code Modulation Techniques (1st ed.). New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-01436-0.

- Bill Waggener (1999). Pulse Code Modulation Systems Design (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Artech House. ISBN 978-0-89006-776-5.

External links

[edit]- PCM description on MultimediaWiki

- Ralph Miller and Bob Badgley invented multi-level PCM independently in their work at Bell Labs on SIGSALY: U.S. patent 3,912,868 filed in 1943: N-ary Pulse Code Modulation.

- Information about PCM: A description of PCM with links to information about subtypes of this format (for example linear pulse-code modulation), and references to their specifications.

- Summary of LPCM – Contains links to information about implementations and their specifications.

- How to control internal/external hardware using Microsoft's Media Control Interface – Contains information about, and specifications for the implementation of LPCM used in WAV files.

- RFC 4856 – Media Type Registration of Payload Formats in the RTP Profile for Audio and Video Conferences – audio/L8 and audio/L16 (March 2007)

- RFC 3190 – RTP Payload Format for 12-bit DAT Audio and 20- and 24-bit Linear Sampled Audio (January 2002)

- RFC 3551 – RTP Profile for Audio and Video Conferences with Minimal Control – L8 and L16 (July 2003)

Pulse-code modulation

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Sampling

Sampling is the initial step in pulse-code modulation (PCM), where a continuous analog signal is transformed into a sequence of discrete-time samples by measuring its amplitude at regular intervals. This process creates a pulse-amplitude modulated (PAM) signal, consisting of narrow pulses whose amplitudes correspond to the instantaneous values of the original waveform at each sampling instant. Uniform sampling ensures that the time between samples, known as the sampling period , is constant, with , where is the sampling frequency.[10] The Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem provides the theoretical foundation for this process, stating that a band-limited continuous-time signal can be perfectly reconstructed from its samples if the sampling frequency is greater than or equal to twice the highest frequency component in the signal, i.e., . This requirement, often called the Nyquist rate, prevents aliasing, a distortion where higher frequencies masquerade as lower ones in the sampled signal. The theorem was first articulated by Harry Nyquist in 1928 regarding telegraph transmission limits and formalized by Claude Shannon in 1949 for communication systems.[11][12] To ensure compliance with the Nyquist-Shannon theorem, an anti-aliasing filter—a low-pass filter—is essential before sampling; it attenuates frequency components above , band-limiting the signal to avoid aliasing artifacts. This filter limits the signal's bandwidth to the Nyquist frequency, preserving the integrity of the sampled representation.[13] In audio applications, sampling converts continuous acoustic waveforms into discrete PAM samples; for instance, human hearing extends to about 20 kHz, so compact discs use a sampling frequency of 44.1 kHz—more than twice this bandwidth—to capture high-fidelity sound without aliasing. These PAM samples form the basis for subsequent PCM stages, such as quantization.[14]Quantization

Quantization in pulse-code modulation (PCM) involves discretizing the amplitude of each sampled signal value from a continuous range to one of a finite set of discrete levels, approximating the original analog signal with a digital representation. In uniform quantization, the full amplitude range from to is divided into equally spaced levels, where is the number of bits per sample, resulting in a fixed step size .[15] This process maps each sample to the nearest quantization level, introducing an inherent approximation that forms the basis of digital signal fidelity in PCM.[16] The difference between the original sample value and its quantized counterpart is known as the quantization error, which manifests as noise in the reconstructed signal. For a uniform quantizer assuming the error is uniformly distributed over to , the mean squared error is . For sinusoidal input signals spanning the full dynamic range, the signal-to-quantization-noise ratio (SQNR) is given by , providing a theoretical measure of quantization performance that improves approximately 6 dB per additional bit.[17] This formula highlights the trade-off between bit depth and noise level, with higher reducing error but increasing bandwidth requirements. Uniform quantizers are categorized into mid-riser and mid-tread types based on the placement of the zero level relative to the decision thresholds. In a mid-riser quantizer, the zero input falls midway between two output levels (e.g., between -1 and +1), resulting in no zero output code and potential DC offset, often using sign-magnitude representation.[18] Conversely, a mid-tread quantizer positions the zero at the center of a quantization interval, including a zero output level for zero input and typically employing two's complement coding, which rounds small signals to zero and avoids offset.[19] These designs influence error characteristics, with mid-tread often preferred for signals crossing zero frequently, such as audio. Quantization errors in PCM arise primarily from two sources: granular noise and overload noise. Granular noise refers to the small-scale distortions within the quantizer's dynamic range, akin to the uniform error distribution in each step, which dominates for signals fitting within the levels.[20] Overload noise occurs when the input amplitude exceeds the maximum representable level, causing clipping and large distortions, mitigated by ensuring the signal stays within to or using headroom in practice.[21] While basic PCM relies on uniform quantization for linearity, non-uniform quantization extends this by effectively varying step sizes through companding—compressing the signal before uniform quantization and expanding it afterward—to allocate finer levels to smaller amplitudes, reducing overall impairment for signals with wide dynamic ranges like speech.[22] This approach maintains the simplicity of uniform coding while improving SQNR for low-level signals without altering the core PCM linearity.Binary Encoding

In the binary encoding stage of pulse-code modulation (PCM), the discrete amplitude levels resulting from quantization are mapped to fixed-length binary codes, forming the pulse codes that represent the original signal for digital transmission or storage.[23] Each quantized level is assigned a unique binary word, typically consisting of bits where the number of levels , allowing representation of distinct values.[24] Common encoding schemes include natural binary coding, where levels are assigned sequential binary numbers (e.g., level 0 as 0000, level 1 as 0001), and Gray coding, which ensures that adjacent levels differ by only one bit to reduce error propagation in noisy channels (e.g., level 0 as 0000, level 1 as 0001, level 2 as 0011).[23][24] The bit rate of the resulting PCM signal is determined by the product of the number of bits per sample and the sampling frequency , given by where is in bits per second.[24] For instance, in telephony applications using 8 bits per sample and an 8 kHz sampling rate, this yields a bit rate of 64 kbps.[23] In multi-channel PCM systems, such as those in digital telephony, binary-encoded samples from multiple channels are organized into time-division multiplexed (TDM) frames to enable efficient transmission.[25] Each frame typically includes one binary word from each channel plus additional synchronization bits for frame alignment and timing recovery at the receiver.[25] For example, the T1 carrier system frames 24 channels using 8-bit PCM words per channel, resulting in a 193-bit frame (24 × 8 + 1 framing bit) transmitted at 8,000 frames per second.[25] As an illustrative example, consider a 16-level quantizer (, ) encoding levels from 0 to 15. In natural binary coding, the assignments are straightforward increments, while Gray coding adjusts for single-bit transitions:| Level | Natural Binary | Gray Code |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0000 | 0000 |

| 1 | 0001 | 0001 |

| 2 | 0010 | 0011 |

| 3 | 0011 | 0010 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 14 | 1110 | 1001 |

| 15 | 1111 | 1000 |